Abstract

Variations in platelet number, volume, and function are largely genetically controlled, and many loci associated with platelet traits have been identified by genome-wide association studies (GWASs).1 The genome also contains a large number of rare variants, of which a tiny fraction underlies the inherited diseases of humans. Research over the last 3 decades has led to the discovery of 51 genes harboring variants responsible for inherited platelet disorders (IPDs). However, the majority of patients with an IPD still do not receive a molecular diagnosis. Alongside the scientific interest, molecular or genetic diagnosis is important for patients. There is increasing recognition that a number of IPDs are associated with severe pathologies, including an increased risk of malignancy, and a definitive diagnosis can inform prognosis and care. In this review, we give an overview of these disorders grouped according to their effect on platelet biology and their clinical characteristics. We also discuss the challenge of identifying candidate genes and causal variants therein, how IPDs have been historically diagnosed, and how this is changing with the introduction of high-throughput sequencing. Finally, we describe how integration of large genomic, epigenomic, and phenotypic datasets, including whole genome sequencing data, GWASs, epigenomic profiling, protein–protein interaction networks, and standardized clinical phenotype coding, will drive the discovery of novel mechanisms of disease in the near future to improve patient diagnosis and management.

Rare inherited platelet disorders

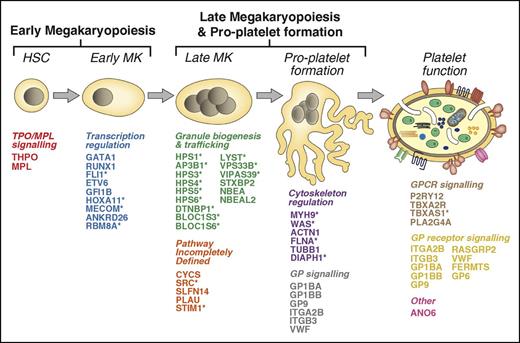

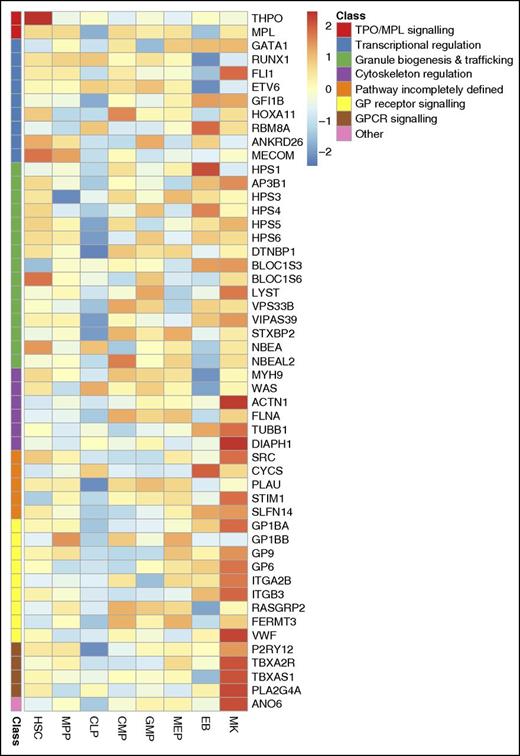

There is marked genetic heterogeneity among inherited platelet disorders (IPDs), and in this section, we survey the 51 genes known to harbor variants responsible for IPDs (henceforth, IPD genes), classified according to their principal known effect on platelet biology. They encode an array of molecules of diverse function, reflecting the complex and tightly regulated processes of megakaryopoiesis, platelet formation, and platelet function (Figure 1). For some genes, their role in platelet biology is less well defined, and this is also discussed. Many IPD genes are widely transcribed across blood cell types (Figure 2) and other tissues. Hence, patients with an IPD frequently present with pathologies reaching well beyond the blood system2 (Figure 1, 23 genes marked with asterisk).

The 51 genes underlying IPDs. The cartoon depicts the process of megakaryopoiesis and platelet formation. Each of the 51 known IPD genes are indicated and categorized according to their effect on megakaryocyte and platelet biology. *IPDs typically associated with phenotypes outside of the blood system. HSC, hematopoietic stem cell.

The 51 genes underlying IPDs. The cartoon depicts the process of megakaryopoiesis and platelet formation. Each of the 51 known IPD genes are indicated and categorized according to their effect on megakaryocyte and platelet biology. *IPDs typically associated with phenotypes outside of the blood system. HSC, hematopoietic stem cell.

Expression levels of 51 genes underlying IPDs across hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. High relative expression is shown in red and low relative expression in blue. The expression of each gene is normalized relative to the mean expression across all samples. Genes are ordered and color-coded according to their predicted effect on platelet biology (as in Fig. 1). Information about the levels of transcripts for the 51 genes determined by RNA-seq was retrieved from Chen et al.103 HSC, hematopoietic stem cell; MPP, multipotent progenitor; CLP, common lymphoid progenitor; CMP, common myeloid progenitor; GMP, granulocyte-monocyte progenitor; MEP, megakaryocyte-erythrocyte precursor; EB, erythroblast; MK, megakaryocyte.

Expression levels of 51 genes underlying IPDs across hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. High relative expression is shown in red and low relative expression in blue. The expression of each gene is normalized relative to the mean expression across all samples. Genes are ordered and color-coded according to their predicted effect on platelet biology (as in Fig. 1). Information about the levels of transcripts for the 51 genes determined by RNA-seq was retrieved from Chen et al.103 HSC, hematopoietic stem cell; MPP, multipotent progenitor; CLP, common lymphoid progenitor; CMP, common myeloid progenitor; GMP, granulocyte-monocyte progenitor; MEP, megakaryocyte-erythrocyte precursor; EB, erythroblast; MK, megakaryocyte.

Megakaryopoiesis and platelet formation

Studies in patients with thrombocytopenia have highlighted the important roles of the Thpo/Mpl signaling pathway and transcriptional regulation in both early and late stages of megakaryopoiesis. Rare variants in THPO and MPL, the genes encoding thrombopoietin3,4 and its receptor Mpl,5,6 cause congenital thrombocytopenia, and 7 IPD genes encode transcription factors (GATA1,7,8 RUNX1,9 FLI1,10 ETV6,11 HOXA11,12 MECOM,13 and GFI1B14,15 ) expressed in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (Figure 2). Rare variants in RBM8A16 and ANKRD2617 have been shown to affect transcription factor binding (of Mecom and Runx1, respectively), altering signaling through the Thpo/Mpl pathway, and resulting in thrombocytopenia, but their exact role in megakaryopoiesis is not yet clear.

Six IPD genes regulate the megakaryocyte cytoskeleton, and the principal effect of deleterious variants is macrothrombocytopenia due to aberrant proplatelet formation (variants in MYH9,18 ACTN1,19 FLNA,20 TUBB1,21 and DIAPH122 ). Causal variants in the Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome (WAS) gene WAS also lead to defective proplatelet formation alongside neutropenia and eczema but, in contrast to other cytoskeletal disorders, the platelets are small.23,24 Thus far, 6 genes encoding proteins that primarily influence granule formation, trafficking, or secretion (NBEAL2,25-27 NBEA,28 VPS33B,29 VIPAS39,30 STXBP2,31,32 and LYST33 ) and 9 genes that cause Hermansky Pudlak syndrome (HPS), a δ-granule platelet disorder (HPS1, AP3B1, HPS3, HPS4, HPS5, HPS6, DTNBP1, BLOC1S3, and BLOC1S634-41 ) have been identified.

Defects in transmembrane glycoprotein (GP) signaling pathways can lead to abnormal platelet function and thrombocytopenia with giant platelets through abnormal proplatelet formation (GP1BA, GP1BB, and GP942,43 ) and thrombasthenia only (ITGA2B and ITGB344,45 ). Gain-of-function (GOF) variants in GP1BA can cause enhanced binding to von Willebrand factor (Vwf), leading to “platelet-type” von Willebrand disease (VWD),46 which is a phenocopy of type 2B VWD, a disorder caused by GOF variants in VWF affecting the function of its A1 domain.47 In both cases, premature interaction between Gp1ba and the Vwf A1 domain results in bleeding characterized by thrombocytopenia and a loss of high-molecular-weight Vwf multimers. DNA analysis is generally required to distinguish between these 2 disorders.

The role of some IPD genes in megakaryopoiesis and proplatelet formation is less well defined. The recent discovery of a GOF variant in SRC causing abnormal megakaryopoiesis and thrombocytopenia has cemented the central role of this universal tyrosine kinase in a variety of megakaryocyte signaling pathways and podosome formation48 ; CYCS is expected to play a role in apoptosis49 ; certain GOF variants in STIM1 (causal of Störmorken syndrome) result in thrombocytopenia with abnormal platelet function and bleeding, whereas loss-of-function (LOF) variants in STIM1 cause an autoimmune thrombocytopenia. LOF variants in ORAI1 have been described in a mild Störmorken-like syndrome, but the platelet defects are not well established. Both Orai1 and Stim1 are involved in calcium homeostasis, and IPD-causing variants consequently affect platelet signaling, but further research is required into their role in platelet formation.50-52 Novel missense variants were recently identified in SLFN14 in 4 unrelated pedigrees with moderate thrombocytopenia and platelet secretion defects. Although the mechanism is not clear, a defect in platelet formation was observed.53,54 Finally, Quebec platelet disorder, thus far confined to French Canadians, is caused by a tandem duplication in PLAU, leading to overexpression of urokinase, and is characterized by thrombocytopenia, degradation of α-granule contents with normal granule structure, decreased aggregation in response to epinephrine, and late-onset bleeding.55

Platelet function

There are 14 IPD genes primarily affecting various aspects of platelet function. Six genes encode GPs that function as receptors for the hemostatically important ligands Vwf (GP1BA, GP1BB, and GP9 gene defects causing Bernard Soulier syndrome [BSS]),43 fibrinogen (ITGA2 and ITGB3 gene defects causing Glanzmann thrombasthenia [GT]),45 and collagen (GP6).56 The typical mode of inheritance for GT is autosomal recessive with LOF variants in ITGA2B or ITGB3. This classical thrombasthenia is reviewed extensively elsewhere,45 but it is worth noting that, again, rare and dominant GOF variants in ITGB3 have also been described, leading to enhanced fibrinogen binding combined with bleeding57 and a mild thrombocytopenia exacerbated during pregnancy but without bleeding.58 Mutations in FERMT3 affect integrin inside-out signaling causing a GT-like platelet phenotype with bleeding and associated with a type III leukocyte adhesion disorder.59 A homozygous variant in RASGRP2 was discovered as a cause of another mild GT-like platelet phenotype in a consanguineous pedigree. RASGRP2 encodes a guanine exchange factor that regulates Rap1b activation and consequently has a major effect on αIIbβ3 (encoded by ITGA2B and ITGB3) signaling in platelets.60

G-protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs) are another main type of multispan transmembrane receptors and signaling defects due to variants in P2YR1261 and TBXA2R62 (encoding the GPCRs for adenosine diphosphate and thromboxane, respectively) or their downstream effectors (TBXAS163 and PLA2G4A64 ) have been linked to IPDs. Scott syndrome does not fall into the aforementioned categories and is caused by autosomal recessive variants in ANO6, which encodes a multispan transmembrane protein involved in phospholipid scrambling.65 Platelets from these cases cannot properly express phosphatidylserine on their surface, which leads to defective coagulation.

Current approaches to diagnosis

IPD diagnosis is straightforward in the major platelet function disorders such as BSS and GT, which often present with severe bleeding symptoms early in life and are easily recognized by the pattern of platelet aggregation defects.45,66 This is often supplemented by assessment of the storage pool either directly by nucleotide assay or lumi-aggregometry. In some IPDs, the platelet function defect and impaired hemostasis are part of well-defined syndromes, eg, Chediak Higashi syndrome and HPS, where the platelet δ-granule defect is typically associated with immune deficiency or ocular albinism, respectively. The presence of syndromic features can help in recognition and diagnosis, but diagnosis remains challenging for the majority of IPDs, which often have a mild platelet phenotype and are clinically heterogeneous. Diagnosis is further complicated by the fact that, for many IPDs, the platelet count is within normal ranges, and the disorder may only become apparent after a hemostatic challenge or if cases present with accompanying pathologies in other organ systems, including malignancies.67

Establishing a conclusive molecular diagnosis is the bedrock of good hematologic practice because it informs optimal treatment and can provide clarity about disease progression. For IPDs, this is particularly important for the severe cases and those associated with early-onset clinical pathologies such as myelofibrosis, lung fibrosis, renal insufficiency, and malignancy. Thrombocytopenias caused by variants in RUNX1, ETV6, and ANKRD269,68,69 are associated with increased risk of myeloid malignancy, whereas for WAS and amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia caused by MPL variants, treatment by allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant or gene therapy may require consideration.70-72 Moreover, genetic counseling can be provided if the diagnosis is confirmed at the DNA level. Current guidelines favor a tiered approach to IPD diagnosis. DNA analysis by Sanger sequencing is at the fourth and final tier and often not applied because of its limited availability and cost.66 Moreover, it is used primarily to confirm an already clinically suspected genetic diagnosis and targets only a single or small group of genes. In the majority of IPDs, a single candidate gene is not readily apparent from standard laboratory tests. Consequently, a molecular diagnosis is given in only a minority of patients, and even when a genetic defect is identified, the number of independent cases remains small for the majority of IPDs.73,74 Fewer than 5 unrelated probands have been identified for IPD genes P2Y12R,75 GP6,76,77 TBXA2R,78 PLAU, and ANO6,79 which all were identified before the era of high-throughput sequencing (HTS), and there is a paucity of larger case series for individual IPD genes with the exception of ACTN180 and ANKRD26.81

This lack of genetic diagnosis not only hampers our ability to provide accurate information on prognosis and optimal management, but the small case numbers also impact on our ability to interpret the pathogenicity of particular variants. The advent of HTS is set to change this. In this issue of Blood, the ThromboGenomics consortium reports on a targeted HTS panel of 76 genes (63 genes in the panel reported in their publication and a further 13 genes added in the currently available version) covering the inherited bleeding, thrombotic, and platelet disorders (BPDs), bringing an affordable molecular diagnosis within reach.82 The application of HTS will simplify the diagnostic process and reduce delay, as we discuss below.

IPD gene discovery to date

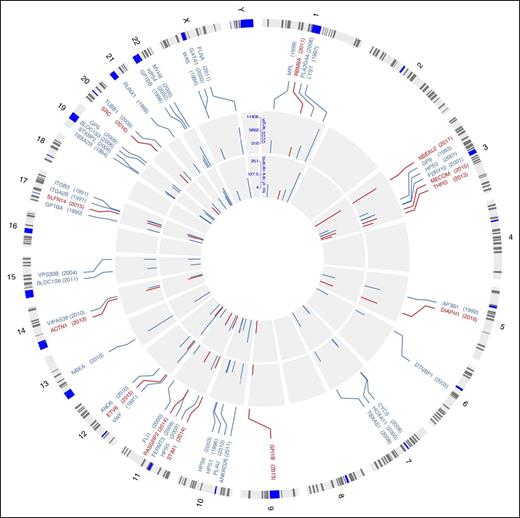

Until recently, the majority of IPD genes have been discovered by candidate gene and linkage studies. These approaches resulted in the identification of 36 IPD genes by 2010, when HTS became available (Figure 3). In 2011, 3 groups reported on NBEAL2 being the causal gene for gray platelet syndrome (GPS),25-27 and 2 of these discoveries were made possible by HTS. In the last 5 years, 14 additional IPD genes have been identified, 11 by applying HTS (Figure 3). Thrombocytopenia with absent radii is an example of a syndrome for which the genetic roots remained elusive despite being clinically well defined for more than 2 decades. It has a thus far unique genetic architecture typically involving a microdeletion on one haplotype and a low-frequency regulatory variant on the other haplotype of RBM8A. The most commonly implicated regulatory variant results in reduced binding of the transcription factor Mecom, leading to an insufficiency of the protein Y14 in megakaryocytes, causing thrombocytopenia.16 In addition, whole exome sequencing (WES) was also instrumental in discovering variants in GFI1B responsible for a GPS-like syndrome14,15 ; ACTN1,19 ETV6,11 STIM1,50 DIAPH1,22 SRC,48 SLFN14,53 and MECOM13 for inherited thrombocytopenias; and RASGRP2 for GT-like disease.60

Genomic location of the 51 genes underlying IPDs. Circos diagram120 illustrating the location of known IPD genes across human chromosomes. Track 1: Cytoband with chromosome name with centromeres in blue. Track 2: Genomic location of 51 established IPD genes and the year in which variants in the gene were first identified as a cause of IPD in humans in brackets. Gene names in red represent genes identified by HTS. Track 3: Log10 of the number of amino acids encoded by the reference CCDS transcript. Log10 scale is indicated at 12 o’clock. Track 4: Log10 of the number of rare variants predicted to affect amino acid sequence observed in 6390 individuals enrolled to the NIHR BioResource–Rare Diseases. Log10 scale is indicated at 12 o’clock.

Genomic location of the 51 genes underlying IPDs. Circos diagram120 illustrating the location of known IPD genes across human chromosomes. Track 1: Cytoband with chromosome name with centromeres in blue. Track 2: Genomic location of 51 established IPD genes and the year in which variants in the gene were first identified as a cause of IPD in humans in brackets. Gene names in red represent genes identified by HTS. Track 3: Log10 of the number of amino acids encoded by the reference CCDS transcript. Log10 scale is indicated at 12 o’clock. Track 4: Log10 of the number of rare variants predicted to affect amino acid sequence observed in 6390 individuals enrolled to the NIHR BioResource–Rare Diseases. Log10 scale is indicated at 12 o’clock.

The results of the rare diseases pilot phase of the 100 000 Genomes Project83 indicate that a large number of IPD genes remain to be discovered. Genome sequencing results of the DNA samples of hundreds of probands with uncharacterized BPDs, analyzed using assigned human phenotype ontology (HPO) terms,2 have helped identify pathogenic variants in known IPD genes in almost 20% of cases. New algorithms to compare cases with similar phenotypes48,84 have been used to identify 2 novel IPD genes (DIAPH1 and SRC)22,48 and several putative ones. This suggests that the majority of cases either harbor pathogenic variants in unknown genes or regulatory regions or are the result of a digenic mode of inheritance.

The lack of gene discoveries on a global scale for δ-granule storage pool disease (δ-SPD) is a case in point. The true prevalence of δ-SPD is unclear, as the definition is not always consistent between studies, but defects in granule release are relatively frequent among the mild IPDs.73,85 The greatest diagnostic success for δ-SPD has been in the multisystem syndromes such as Chediak Higashi syndrome and HPS, but most patients with nonsyndromic δ-SPD remain undiagnosed.86 In ongoing large-scale HTS projects such as Genotyping and Phenotyping of Platelets87,88 and BRIDGE-BPD,2,22,48 the lack of gene discovery for δ-SPD, even in these large patient cohorts, highlights a need to analyze the noncoding regulatory regions of the genome via whole genome sequencing (WGS) while also exploring novel methods of data analysis and integration. We discuss such methods in more detail in the final section.

Assigning pathogenicity to novel variants: use of public databases

With the advent of HTS, it has become possible to survey the exonic fraction of large numbers of genomes for variants by WES. Exomes comprise ∼2% of the genome (∼64 Mb), whereas current WGS typically captures >98% of the 3.2 billion bases of the genome at a minimum of 15× coverage. Information about pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants is maintained in databases, but until recently, it was not possible to verify their allele frequencies in the general population. Several initiatives such as the 1000 Genomes89 and UK10K90 projects and initiatives to aggregate results from many smaller WES projects, as achieved by the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC),91 have provided information on exonic variants observed in >71 000 individuals of mainly European ancestry. This catalog has made an immense contribution to improving the accuracy of assignment of pathogenicity to DNA variants observed in IPD cases. There is still a relative paucity of sequencing data from individuals of other ethnicities. Consequently, a larger number of variants absent from control samples is observed in their DNA, making it harder to distinguish variants that are relatively common in particular populations from variants responsible for disease.

HTS has also made possible large-scale WGS projects such as the 100 000 Genomes Project,83 which are complemented by genome-wide association studies (GWASs) in large population cohorts such as the UK Biobank of 500 000 healthy individuals.92 Both projects link genotypes with health and social care records and will lead to a better understanding of the relationship between variants and diseases. In particular, they will allow more accurate assignment of pathogenicity to rare variants underlying the thousands of inherited diseases. Single nucleotide variants (SNVs) can be called accurately by WES, but calling of short insertions and deletions and especially of copy number and structural variants is more challenging. Here, WGS can achieve far greater sensitivity and specificity than WES. WGS will therefore further improve the accuracy of frequencies for all classes of variants in databases, make it easier to discover the genetic determinants of rare inherited diseases, and open up opportunities to explore the noncoding regulatory part of the genome.

Germline variants are inevitable consequences of meiosis and DNA repair and accumulate over generations. Given the existence of many nonpathogenic variants in any individual’s genome, the main challenge faced by researchers when interpreting HTS data of an IPD case is determining which variants are causing the disorder. The correct identification of novel causal variants critically depends on their allele frequency in relevant control samples.93 Additionally, studies are required to uncover the function of novel genes and the consequences of candidate rare variants. It has been shown that specific GOF variants in DIAPH1 and SRC can cause a defect in megakaryopoiesis, whereas this is not expected of LOF variants.22,48 Similar observations can be made for SFLN14, where all variants are located in the ATPase-AAA-4 domain, and rare variants outside this domain seem not to result in an IPD.54

There are publicly accessible databases such as ClinVar,94 DECIPHER,95 and Exome variant server96 and access-for-a-fee databases such as the Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD)97 that record disease-associated variants. HGMD maintains a catalog of high-penetrance variants derived from the literature.97 None of these databases are 100% accurate: for example, 539 rare variants denoted as disease causing in HGMD were observed in the 1000 Genomes Project at a frequency >1%,98 and 140 variants in IPD genes showed a frequency in the ExAC database of >0.1%, yet the evidence supporting a claim to pathogenicity was deemed insufficient for all but 4 variants.82

In conclusion, large-scale population sequencing projects have greatly enhanced our ability to interpret the pathogenicity of potential candidate IPD-causing variants, but there are pitfalls: any rare variant must be interpreted in the context of the ethnicity of the individual and great care must be taken not to overinterpret the pathogenicity of novel variants absent from control datasets, even in established IPD genes, without further evidence from functional studies or observation of the same variant in several unrelated cases with similar phenotypes.

Future of IPD gene discovery

HTS will undoubtedly assist the discovery of variants causing IPDs in many new genes over the next decade, but genomic sequencing alone cannot explain the mechanisms underlying the relationship between genotype and phenotype in cases with an apparent inherited disorder.99 To ascertain the functional consequences of rare variants, it is essential that knowledge of phenotypes and pathways is integrated systematically within a frame of reference similar to that of the human genome.100

Data from a wide variety of sources, including GWASs, Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man, and mouse genome databases can be used to annotate candidate regions and better understand individual proteins and their roles in pathways relevant to megakaryopoiesis and platelet formation. Identification of the regulatory DNA elements has become feasible thanks to the results from projects like ENCODE,101 Roadmap,102 and Blueprint,103 coordinated by the International Human Epigenome Consortium (IHEC). Integration of different layers of information, including methylation and histone modification states, expression quantitative trait loci data, transcriptomics, and proteomics, requires the development of new statistical methods. Some insights on how this richness of information can aid the discovery of novel causes of disease will be discussed in the following sections.

Human phenotype ontology

In order to discover novel variants responsible for disease, cases sharing similar clinical and laboratory phenotypes need to be identified, and new methods have been sought to cluster similar cases in the ever-growing cohorts undergoing genome sequencing. One of the widely used phenotype annotation standard for rare diseases is the HPO terms system.104 HPO coding is used by the Deciphering of Developmental Disorders105 and 100 000 Genomes Projects, and thus far, 1247 probands with BPDs have been HPO coded.2 This revealed the presence of nonhematological pathologies in 60% of cases, particularly in the central nervous (eg, autism spectrum disorder), skeletal (eg, osteoporosis), and immune systems.2 This insight into the more complex spectrum of pathologies in IPD cases is important for the provision of care, which often warrants a multidisciplinary approach. Additionally, standardized phenotyping by means of HPO terms is critical for IPD gene discovery across large collections of cases. Indeed, genome sequencing combined with HPO coding supported the identification of the DIAPH1 variant in 2 unrelated pedigrees with similar phenotype terms thrombocytopenia and deafness.22 It also allowed integration with existing phenotype databases, such as the one for mouse phenotype ontology terms, which aided the discovery of the SRC variant because cases and knockout mice shared HPO terms.48 These discoveries are critically dependent on new statistical methods that exploit the power of HPO-based patient coding together with genotypes obtained by sequencing.84,106,107

To discover which genes are pertinent to the remaining IPDs, screening of large case collections will be essential. The small number of reported independent cases in the majority of IPDs and the lack of discovery in SPD to date indicate that extremely large collections are needed to bring together adequate numbers of unrelated index cases with a shared genetic basis. International collaboration is therefore warranted and will also bring together expertise about the clinical evolution of disease for each of the IPD genes. This collaborative approach will provide the platform to evaluate existing and new interventions to gather evidence for the best approach to treatment. That such international approaches can be successful has been demonstrated by the BRIDGE-BPD and ThromboGenomics consortium efforts reported in this issue22,82 and in other journals.48,84

Noncoding regulatory space

The genome comprises 3.2 billion bp, 98% of which do not form part of a recognized gene. The nonexonic portion of the genome is largely regulatory in nature, but the landscape of regulatory elements differs between cell types. The aforementioned IHEC initiatives have generated accurate maps of regulatory elements. The discoveries that specific heterozygous GOF variants in the 5′ untranslated region of ANKRD26 cause thrombocytopenia108 and that the vast majority of thrombocytopenia with absent radii syndrome cases of Northern European ancestry are due to compound inheritance of an RBM8A-null allele and a low-frequency SNV in its 5′ untranslated region16 indicate that cell-specific knowledge of the regulatory space may help to identify novel mechanisms of disease in future. It is likely that similar noncoding regulatory variants in known or novel IPD genes remain to be discovered, and integrating IHEC reference epigenome maps with the catalog of blood cell type–specific transcript isoform use can help interpret the consequence of noncoding DNA variants observed in IPD cases.103 The exploration of the noncoding portion of the genome for variants causal of IPDs requires many parallel approaches recognizing the complexity of the regulatory networks at play. For example, the cell-specific role of noncoding RNAs has been recently highlighted.109 Finally, the rapidly accumulating chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-seq data defining the binding sites for transcription factors in different cell types, including data generated in megakaryocytes, will also be of value.110

GWAS for platelet traits

Meta-analysis of GWASs for blood cell traits has led to the discovery of nearly 200 common SNVs exerting small effects on blood cell indices.111 These variants mark known and new genomic regions important for hematopoiesis and blood cell survival. With GWASs being performed on ever-larger population samples such as the UK Biobank and Million Veteran cohorts, the number of associated SNVs is predicted to rise substantially, with increasing numbers of rare variants with larger effect sizes being revealed. A picture is therefore emerging of hundreds of genes identified by GWASs controlling the life cycle of platelets, and the maximum effect sizes of variants in these genes on platelet traits are inversely correlated with their minor allele frequencies due to selection. This assumption is illustrated by recent observations in TUBB1. The common noncoding SNV rs4812048 was linked with an effect on platelet volume by GWASs,1 and rare nonsynonymous SNVs have since been reported as a cause of macrothrombocytopenia in humans.21,112-114 This suggests that integrating knowledge about GWAS loci affecting platelet indices alongside genome sequencing data of collections of patients with IPDs of unknown molecular etiology may reveal novel candidate genes.

Protein–protein interaction networks

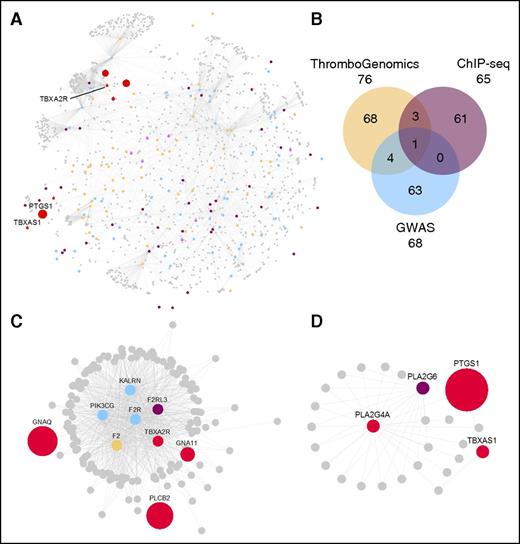

Knowledge about the molecules and pathways underlying megakaryopoiesis and the formation of platelets is rapidly expanding. Bringing knowledge gathered from GWASs111 and inherited BPDs (the 76 BPD genes reported by Simeoni et al82 ) together with information about genes identified by ChIP-seq,110 we defined 200 unique genes deemed important for these processes (Figure 4B). The proteins encoded by these “seed genes” were used as baits to retrieve their first-order interactors from the Reactome and IntAct databases using previously reported informatics approaches.1,115 This information was displayed as a protein–-protein interaction network (PPIN) consisting of 1684 proteins (nodes) connected by 5360 biochemical interactions (edges) using the Cytoscape application (Figure 4A). To make this PPIN, which encompasses knowledge from thousands of publications available to the scientific and medical communities in a format allowing its unrestricted use, we made a Cytoscape file available for download (supplemental Data, available on the Blood Web site). For example, it can be used to resolve IPDs with digenic roots as illustrated by observations in TBXA2R: 4 reports describe LOF variants of TBXA2R in patients with platelet defects as a dominant finding.78,116-118 Although heterozygosity for the TBXA2R variants correlated with the platelet defect in these carriers, there was no association with bleeding problems. It was noted that a potential second genetic factor would be required to cause bleeding. Two subnetworks (Figure 4C-D) of proteins important for the signaling events downstream of the thromboxane receptor (Figure 4C) and for the synthesis of thromboxane (Figure 4D) may highlight potential candidates for this second gene. Indeed, we observed a case with severe bleeding and a LOF variant in TBXA2R (Figure 4C) and a second putative causal variant was identified in PTGS1, which encodes cyclooxygenase-1.119

Protein–protein interaction network reflecting the molecules and pathways implicated in megakaryopoiesis, the formation of platelets, thrombosis, and hemostasis. (A) PPIN of 1684 nodes (proteins) connected by 5360 edges (biochemical reactions). The 1517 first-order interacting nodes and all but 24 of the 5360 edges were obtained from the Reactome (n = 3625) and IntAct (n = 1711) databases. The 24 edges were added on the basis of manual literature curation. (B) The 200 baits are colored as per the Venn diagram, except for the 8 baits present in >1 category, which are pink, and the 8 prototype proteins involved in the synthesis of thromboxane and signaling via the thromboxane receptor (Tbxa2r) pathway. The Venn diagram shows the 3 gene sets in ochre, blue, and purple for the ThromboGenomics HTS test platform gene set,82 the platelet volume and count GWAS gene set,1 or the gene set identified by ChIP-seq in human megakaryocytes and showing binding of all 5 transcription factors (Fli1, Gata1, Gata2, Runx1, and Tal1) at their promoter,110 respectively. (C-D) Subnetworks retrieved from the PPIN in A. (C) A subnetwork of 156 nodes and 874 edges obtained by retrieving the first-order interactors of Tbxa2r, the receptor for thromboxane. (D) A subnetwork of 26 nodes and 42 edges involved in the synthesis of thromboxane and obtained by selecting the first-order interactors of Tbxas1 (thromboxane synthase 1) and Pla2g4a (phospholipase A2). The red nodes in C and D are a set of prototype proteins related to thromboxane synthesis and signaling and the other colored nodes are baits. The surface areas of the red colored nodes in A and all colored nodes in C and D reflect their transcript level determined by sequencing of RNA from human megakaryocytes (data retrieved from Chen et al).103 An interactive version of the network, containing gene expression levels and other annotation features, is available for download in Cytoscape format from the supplemental Data.

Protein–protein interaction network reflecting the molecules and pathways implicated in megakaryopoiesis, the formation of platelets, thrombosis, and hemostasis. (A) PPIN of 1684 nodes (proteins) connected by 5360 edges (biochemical reactions). The 1517 first-order interacting nodes and all but 24 of the 5360 edges were obtained from the Reactome (n = 3625) and IntAct (n = 1711) databases. The 24 edges were added on the basis of manual literature curation. (B) The 200 baits are colored as per the Venn diagram, except for the 8 baits present in >1 category, which are pink, and the 8 prototype proteins involved in the synthesis of thromboxane and signaling via the thromboxane receptor (Tbxa2r) pathway. The Venn diagram shows the 3 gene sets in ochre, blue, and purple for the ThromboGenomics HTS test platform gene set,82 the platelet volume and count GWAS gene set,1 or the gene set identified by ChIP-seq in human megakaryocytes and showing binding of all 5 transcription factors (Fli1, Gata1, Gata2, Runx1, and Tal1) at their promoter,110 respectively. (C-D) Subnetworks retrieved from the PPIN in A. (C) A subnetwork of 156 nodes and 874 edges obtained by retrieving the first-order interactors of Tbxa2r, the receptor for thromboxane. (D) A subnetwork of 26 nodes and 42 edges involved in the synthesis of thromboxane and obtained by selecting the first-order interactors of Tbxas1 (thromboxane synthase 1) and Pla2g4a (phospholipase A2). The red nodes in C and D are a set of prototype proteins related to thromboxane synthesis and signaling and the other colored nodes are baits. The surface areas of the red colored nodes in A and all colored nodes in C and D reflect their transcript level determined by sequencing of RNA from human megakaryocytes (data retrieved from Chen et al).103 An interactive version of the network, containing gene expression levels and other annotation features, is available for download in Cytoscape format from the supplemental Data.

Conclusion

HTS has enabled the discovery of many novel IPD genes in the last 5 years, and this new knowledge can be rapidly integrated in diagnostic platforms such as the ThromboGenomics HTS test, which will simplify and hasten diagnosis of IPDs. There is, however, still an immense challenge to resolve the genetic basis of the remaining IPDs and to gather better evidence for the best treatments. This can only happen through international collaboration and knowledge sharing. We must seek permission from patients and their families to share their genotype and phenotype data and invest in standardized phenotyping using internationally agreed terms like those of the HPO system. There is also an obligation for the research and clinical communities to pursue the development of informatics environments for the safe sharing of anonymized and linked-anonymized data. WGS combined with emerging data from GWASs, ChIP-seq, proteomics, and mouse knockout studies among others will also help explore the noncoding regulatory space and identify novel candidate IPD genes and variants.

Finally, as there are many potential pitfalls when interpreting the role of novel rare variants, it is important to apply rigorous standards when assigning pathogenicity. Providing a molecular diagnosis to patients is highly desirable, but making incorrect assumptions about variants could be harmful.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the members of the BRIDGE-bleeding, thrombotic, and platelet disorders (BPD) and ThromboGenomics Consortia for their contributions. The BRIDGE-BPD and ThromboGenomics studies, including the enrollment of cases, sequencing, and analysis, received support from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) BioResource–Rare Diseases. The NIHR BioResource is funded by the NIHR. We gratefully acknowledge the patients and their relatives who participated in the NIHR BioResource–Rare Diseases studies, without whom much of this research would not be possible. The contributions by Jo Westmoreland (Medical Research Council Laboratory of Molecular Biology) and Dr Myrto Kostadima and Stuart Meacham (University of Cambridge, Ouwehand Group) in creating Figures 1, 2, and 4, respectively, are acknowledged.

M.A.L. and W.H.O. are Co-chairs of the BRIDGE-BPD consortium; K.F. and W.H.O. are Co-chair and Chair of the Scientific and Standardization Committee (SSC) on “Genomics in Thrombosis and Haemostasis” of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis. This SSC oversaw the development of the ThromboGenomics HTS test referred to in this review and described by Simeoni et al in this issue of Blood.82

C.L. is the recipient of a Clinical Research Training Fellowship award from the MRC and M.A.L. and C.L. are also supported by the Imperial College London NIHR Biomedical Research Centre. E.T. is supported by the NIHR BioResource and research in the Ouwehand laboratory receives support from the British Heart Foundation, European Commission, MRC, NHS Blood and Transplant, NIHR and Wellcome Trust.

Authorship

Contribution: C.L. wrote the paper; E.T. performed data analysis and edited the manuscript; and K.F., M.A.L. and W.H.O. edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The members of the BRIDGE-BPD Consortium are listed in the supplemental Data of Stritt et al, in this issue of Blood.22 The members of the ThromboGenomics Consortium are listed in the author list of Simeoni et al, in this issue of Blood.82

Correspondence: Willem H. Ouwehand, Department of Haematology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge Biomedical Campus, Long Rd, Cambridge CB2 0PT, United Kingdom; e-mail: who1000@cam.ac.uk.