Key Points

A gain-of-function variant in DIAPH1 causes macrothrombocytopenia and hearing loss and extends the spectrum of DIAPH1-related disease.

Our findings of altered megakaryopoiesis and platelet cytoskeletal regulation highlight a critical role for DIAPH1 in platelet formation.

Abstract

Macrothrombocytopenia (MTP) is a heterogeneous group of disorders characterized by enlarged and reduced numbers of circulating platelets, sometimes resulting in abnormal bleeding. In most MTP, this phenotype arises because of altered regulation of platelet formation from megakaryocytes (MKs). We report the identification of DIAPH1, which encodes the Rho-effector diaphanous-related formin 1 (DIAPH1), as a candidate gene for MTP using exome sequencing, ontological phenotyping, and similarity regression. We describe 2 unrelated pedigrees with MTP and sensorineural hearing loss that segregate with a DIAPH1 R1213* variant predicting partial truncation of the DIAPH1 diaphanous autoregulatory domain. The R1213* variant was linked to reduced proplatelet formation from cultured MKs, cell clustering, and abnormal cortical filamentous actin. Similarly, in platelets, there was increased filamentous actin and stable microtubules, indicating constitutive activation of DIAPH1. Overexpression of DIAPH1 R1213* in cells reproduced the cytoskeletal alterations found in platelets. Our description of a novel disorder of platelet formation and hearing loss extends the repertoire of DIAPH1-related disease and provides new insight into the autoregulation of DIAPH1 activity.

Introduction

Platelet formation by megakaryocytes (MKs) requires an ordered sequence of differentiation steps from hematopoietic stem cells, followed by MK maturation during which repeated rounds of DNA replication without cell division usually result in very large MKs with a single nucleus and DNA contents up to 128N. This process enables the accumulation of platelet-specific granules and an invaginated membrane system that will later contribute to the platelet cytoplasmic contents and surface membrane.1,2 Platelets are generated from mature MKs by the protrusion of cytoplasmic extensions termed proplatelets into bone marrow sinusoids, where final platelet sizing and shaping occurs.3 Platelet formation strongly depends on microtubules, which enable proplatelet elongation and transport of organelles from the MK cytoplasm,1 and on actin-dependent processes, which mediate the branching of elongating proplatelets, thereby determining the number of available proplatelet tips to form platelets.4

Altered regulation of platelet formation is a feature of several human hematopoietic disorders, including macrothrombocytopenia (MTP), in which circulating platelets are enlarged and reduced in number, sometimes resulting in abnormal bleeding.5,6 MTP has been associated with pathogenic variants in genes that regulate MK maturation (GATA1, GFI1B, and NBEAL2) or that encode platelet surface proteins (GP1BA, GP1BB, GP9, ITGA2B, and ITGB3; reviewed in Pecci and Balduini5 ). However, a prevalent subgroup of MTP arises from variants in ACTN1,7 FLNA,8 MYH9,9,10 TUBB1,11 and PRKACG12 that encode MK cytoskeletal proteins or interactors. It has been proposed that the platelet phenotype associated with some MYH9,13,14 ACTN1,7 and TUBB115 variants results from aberrant cytoskeletal rearrangements during proplatelet formation, leading to altered platelet production. Cytoskeletal dysfunction may also underlie phenotypes such as hearing loss, cataract, and glomerulopathy associated with some variants in MYH9,10,16 and periventricular nodular heterotopia and otopalatodigital syndromes associated with some variants in FLNA.8

Here, we extend the repertoire of MTP by reporting the discovery of a new dominant syndromic disorder of platelet formation. We show that MTP is linked to sensorineural hearing loss in 2 unrelated pedigrees and that this phenotype segregates with the same chain-truncating variant in DIAPH1 that encodes the cytoskeletal regulator and Rho-effector diaphanous-related formin 1 (DIAPH1, or mDia1), identified previously as a regulator of megakaryocytopoiesis in vitro.17

Methods

Recruitment of cases and genetic analysis

The cases were enrolled to the Biomedical Research Centres/Units Inherited Diseases Genetic Evaluation–Bleeding and Platelet Disorders (BRIDGE-BPD) study (UK REC10/H0304/66) or the French study “Network on the inherited diseases of platelet function and platelet production” (INSERM RBM 04-14) after they provided informed written consent. Control groups comprised other cases with BPD of unknown genetic basis or with unrelated rare disorders enrolled to the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) BioResource–Rare Diseases study (UK REC 13/EE/0325). Data collection, human phenotype ontology (HPO) coding, and high-throughput sequencing were performed as previously reported.18 Splice site, frameshift, stop-gain/loss or start-loss variants were analyzed further if they were less frequent than 1 in 10 000 in the Exome Aggregation Consortium database and 1 in 100 in our in-house database. Candidate genes for BPD were identified by phenotype similarity regression19 to allow for the high degree of phenotypic and genetic heterogeneity among the BPD cases.

Platelet imaging

Fixed peripheral blood smears were stained with May-Grünwald-Giemsa stain. Transmission electron microscopy was performed on platelets fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde. Platelet characteristics were measured in a minimum of 99 sections for each case using ImageJ as described previously.8 Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical significance was determined by Student t test for continuous variables, and by the χ2 test for categorical variables. P < .01 was considered statistically significant.

MK colony culture and analysis

CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells were isolated from peripheral blood by magnetic cell sorting and differentiated into MKs as described previously in plate and liquid cultures.20,21 MK colony-forming units (CFU-MKs) and MKs were visualized by light or confocal microscopy after staining with May-Grünwald-Giemsa stain, phalloidin, or anti-CD61 antibodies. Proplatelet formation in liquid MK cultures was determined by light microscopy and ploidy by flow cytometry as described previously.21

DIAPH1 expression in cell lines

The DIAPH1-R1213* complementary DNA (cDNA) was generated by site-directed mutagenesis of the full-length wild-type DIAPH1 cDNA and cloned into the pCMV6-Fc-S (Origene, Rockville, MD) mammalian expression vector, before transient transfection into human embryonic kidney (HEK293FT) or adenocarcinomic human alveolar basal epithelial (A549) cells, cultured using standard conditions.

Western blotting and immunofluorescence microscopy

Denatured washed platelet or transfected HEK293FT cell lysates were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and blotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. The membranes were probed with primary antibodies recognizing DIAPH1, DIAPH3, DIAPH2, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, α-tubulin, tyrosinated tubulin (Tyr-tub), detyrosinated tubulin (Glu-tub), and acetylated tubulin (ac-tub).

For confocal microscopy, transfected A549 cells or platelets applied to fibrinogen-coated coverslips were fixed and probed with antibodies recognizing tubulin or DIAPH1 as described earlier. Filamentous actin (F-actin) was stained using phalloidin-Atto647N. Where indicated, platelets were preincubated with 10 μM colchicine. Platelets and cells were visualized by confocal microscopy as reported previously.22

Microtubule sedimentation and cold-induced disassembly

Polymerized and soluble microtubule fractions were prepared from lysates of resting or colchicine-treated (10 μM) platelets and from resting or SMIFH2 (small-molecule inhibitor of formin homology [FH]2 domain)-treated (25 μM) transfected HEK293FT cells by centrifugation for 30 minutes at 100 000g and 37°C. Microtubule fractions were visualized by western blot analysis. Microtubules were depolymerized by incubation of platelets at 4°C or with colchicine (10 μM). Reassembly was allowed by subsequent rewarming at 37°C as previously reported.22-24

Detailed methods and uncropped images of western blots are provided in supplemental Methods and supplemental Figures, respectively, available on the Blood Web site.

Results

Selection of DIAPH1 as a candidate gene for MTP

We identified DIAPH1 as a novel candidate gene for MTP by analyzing data from 702 index cases with bleeding or platelet disorders of unknown genetic basis recruited to the BRIDGE-BPD study of the NIHR BioResource–Rare Diseases. Control data were analyzed from 3453 cases with unrelated rare disorders or unaffected pedigree members recruited to other branches of the NIHR BioResource–Rare Diseases.

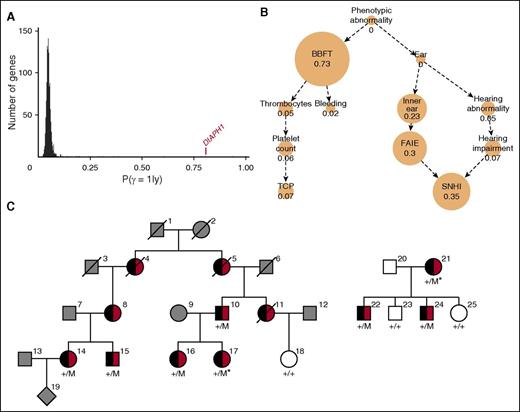

There were 1073 genes for which at least 2 BPD cases carried a rare variant predicted to have a high impact on gene translation. After phenotype similarity regression analysis of the genes in this group, DIAPH1 had the highest probability for the model specifying a statistical association between phenotype and genotype for which thrombocytopenia was inferred (P (γ = 1|y) = 0.81; Figure 1A) The inferred characteristic phenotype for DIAPH1 primarily comprised the HPO terms “Sensorineural hearing impairment” and “Abnormality of blood and blood-forming tissues,” with the latter driven by the terms “Thrombocytopenia” and “Abnormal bleeding” (Figure 1B).

DIAPH1 is a candidate gene for macrothrombocytopenia and hearing loss. (A) Each BPD index case was coded using HPO terms relating to hematologic features and to phenotypes in other organ systems and underwent high-throughput sequencing.18 Candidate genes for BPD were identified by similarity regression in which “baseline” and “alternate” statistical models are compared for every gene.19 Under the baseline model, all cases are assumed to have the same log odds of carrying a rare variant. Under the alternate model, which we give a prior probability of .05 of being the true model, the log odds is modeled as a linear function of the phenotypic similarity of each case to an HPO-encoded “characteristic phenotype.” The characteristic phenotype (φ) and a binary variable indicating the true model (γ) are inferred from the genotype and phenotype data. A high posterior mean for γ is indicative of a potential association between the presence of a rare variant in a gene, coded by a binary vector y, and a disorder characterized by φ. The histogram indicates the mean posterior probability of the alternate model being true (P(γ = 1|y)) for all 1073 genes in which at least 2 BPD cases carry a high-impact variant. The value for DIAPH1 is indicated in red. (B) The inferred HPO-coded characteristic phenotype (φ) for DIAPH1 is represented as a graph, whereby each edge denotes an “is a” relationship and each node contains an HPO term with its marginal posterior probability of inclusion in φ, which is also represented by the node size. When a node and all its descendants in the HPO graph have a marginal posterior probability of inclusion in φ <0.02, it is not shown. (C) Pedigrees of the index cases (*) in which the colored symbols indicate macrothrombocytopenia (black) and hearing loss (red). The gray symbols indicate that the clinical phenotype is unknown, and the white symbols indicate no macrothrombocytopenia or hearing loss. Genotyped cases are indicated by +/M for the heterozygous DIAPH1 R1213* variant and by +/+ for the reference sequence at that locus. BBFT, Abnormality of blood and blood forming tissues; Bleeding, Abnormal bleeding; Ear, Abnormality of the ear; FAIE, Functional abnormality of the inner ear; Inner ear, Abnormality of the inner ear; Platelet count, Abnormal platelet count; SNHI, Sensorineural hearing impairment; Thrombocytes, Abnormality of thrombocytes; TCP, Thrombocytopenia.

DIAPH1 is a candidate gene for macrothrombocytopenia and hearing loss. (A) Each BPD index case was coded using HPO terms relating to hematologic features and to phenotypes in other organ systems and underwent high-throughput sequencing.18 Candidate genes for BPD were identified by similarity regression in which “baseline” and “alternate” statistical models are compared for every gene.19 Under the baseline model, all cases are assumed to have the same log odds of carrying a rare variant. Under the alternate model, which we give a prior probability of .05 of being the true model, the log odds is modeled as a linear function of the phenotypic similarity of each case to an HPO-encoded “characteristic phenotype.” The characteristic phenotype (φ) and a binary variable indicating the true model (γ) are inferred from the genotype and phenotype data. A high posterior mean for γ is indicative of a potential association between the presence of a rare variant in a gene, coded by a binary vector y, and a disorder characterized by φ. The histogram indicates the mean posterior probability of the alternate model being true (P(γ = 1|y)) for all 1073 genes in which at least 2 BPD cases carry a high-impact variant. The value for DIAPH1 is indicated in red. (B) The inferred HPO-coded characteristic phenotype (φ) for DIAPH1 is represented as a graph, whereby each edge denotes an “is a” relationship and each node contains an HPO term with its marginal posterior probability of inclusion in φ, which is also represented by the node size. When a node and all its descendants in the HPO graph have a marginal posterior probability of inclusion in φ <0.02, it is not shown. (C) Pedigrees of the index cases (*) in which the colored symbols indicate macrothrombocytopenia (black) and hearing loss (red). The gray symbols indicate that the clinical phenotype is unknown, and the white symbols indicate no macrothrombocytopenia or hearing loss. Genotyped cases are indicated by +/M for the heterozygous DIAPH1 R1213* variant and by +/+ for the reference sequence at that locus. BBFT, Abnormality of blood and blood forming tissues; Bleeding, Abnormal bleeding; Ear, Abnormality of the ear; FAIE, Functional abnormality of the inner ear; Inner ear, Abnormality of the inner ear; Platelet count, Abnormal platelet count; SNHI, Sensorineural hearing impairment; Thrombocytes, Abnormality of thrombocytes; TCP, Thrombocytopenia.

Two index cases from different pedigrees in the BRIDGE-BPD collection (Bordeaux case 17 and Bristol case 21; Figure 1C) harbored the same high-impact variant in DIAPH1. This was a heterozygous c.3637C>T transition, annotated relative to the DIAPH1 isoform ENST00000398557, which encodes the consensus coding sequence–annotated DIAPH1 protein (UNIPROT O60610). This predicted the substitution of the conserved (PhyloP P = 5.25 × 10−4) arginine at amino acid position 1213 with a premature stop codon (R1213*; Figure 2). This variant was not observed in any of the 61 486 exomes in the Exome Aggregation Consortium database nor in the remaining 4151 exomes sequenced in-house. Sanger sequencing showed that the R1213* variant was present in 6 further pedigree members with both MTP and sensorineural hearing loss but was absent in 3 asymptomatic pedigree members, indicating segregation with the DIAPH1 genotype (P = 3.66 × 10−4, conditional on the genotypes of the index cases; Figure 1C). We found no other rare variants shared by the index cases within 10 Mb around DIAPH1. The sequencing data provided no evidence that these cases were closely related at the genome-wide level or more locally within the DIAPH1-containing chromosome 5 (supplemental Figure 1).

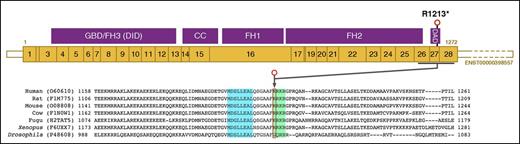

Location of the DIAPH1 R1213* variant. Schematic representation of the major MK DIAPH1 transcript ENST00000398557, which is predicted to encode the 1272–amino acid DIAPH1 protein. R1213 is 60 amino acids from the carboxyl terminus of DIAPH1 within the DAD. In the amino acid sequence lineup of human DIAPH1 and orthologs, there is conservation of the core MDxLLExL (blue box) and basic RRKR (green box) motifs within the DAD that mediate autoinhibitory interactions with the DID near the amino terminus of DIAPH1. Because R1213 is at position 1 of the basic RRKR motif, R1213* is predicted to cause expression of a truncated DIAPH1 protein with an intact core MDxLLExL motif, but without the basic RRKR motif. CC, coiled-coil; GBD, GTPase-binding domain.

Location of the DIAPH1 R1213* variant. Schematic representation of the major MK DIAPH1 transcript ENST00000398557, which is predicted to encode the 1272–amino acid DIAPH1 protein. R1213 is 60 amino acids from the carboxyl terminus of DIAPH1 within the DAD. In the amino acid sequence lineup of human DIAPH1 and orthologs, there is conservation of the core MDxLLExL (blue box) and basic RRKR (green box) motifs within the DAD that mediate autoinhibitory interactions with the DID near the amino terminus of DIAPH1. Because R1213 is at position 1 of the basic RRKR motif, R1213* is predicted to cause expression of a truncated DIAPH1 protein with an intact core MDxLLExL motif, but without the basic RRKR motif. CC, coiled-coil; GBD, GTPase-binding domain.

The R1213* variant predicts DIAPH1 protein truncation

DIAPH1 is a homodimeric formin-family protein that promotes actin assembly and regulates microtubule stability through an FH1 domain that contains binding sites for profilin, and an FH2 domain that promotes nucleation and elongation of actin filaments and possibly microtubule interactions.25-27 DIAPH1 is regulated by a diaphanous autoregulatory domain (DAD) near the carboxyl terminus, which inhibits DIAPH1 activity through an interaction with the diaphanous inhibitory domain (DID) near the amino terminus (Figure 2). Autoinhibition is normally released by competitive binding of activated Rho GTPases, enabling cytoskeletal remodeling.28,29 The inhibitory DAD-DID interaction is mediated by “core” MDxLLExL and “basic” RRKR motifs in the DAD (Figure 2) that bind cognate DID sequences.30

Reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction and amplification of the R1213 region with subsequent restriction endonuclease digestion proved the presence of both wild-type and DIAPH1 R1213* messenger RNA transcripts in platelets from cases 10 and 16 (supplemental Figure 2). The premature stop codon created by the DIAPH1 R1213* variant occurs at position 1 of the RRKR motif (residues 1213-1216) but is closer to the DIAPH1 carboxyl terminus than the MDxLLExL motif (residues 1199-1206). Therefore, the predicted consequence of the R1213* variant is expression of DIAPH1 protein with a truncation within the DAD, resulting in loss of the RRKR motif, but not the MDxLLExL motif (Figure 2).

DIAPH1 R1213* is associated with syndromic MTP and hearing loss and frequently with mild neutropenia

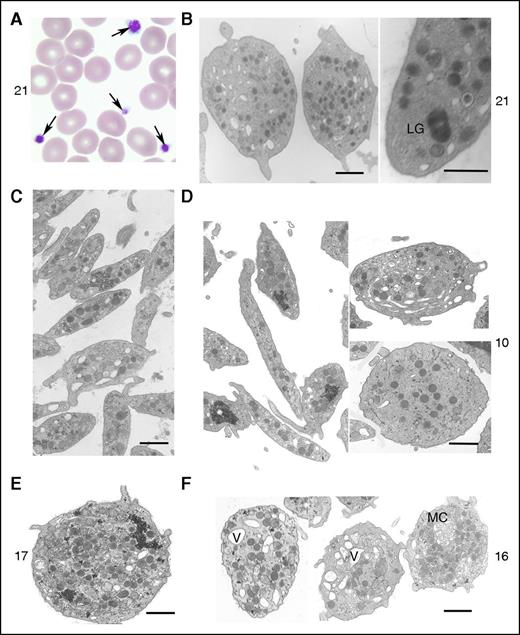

All 8 genotyped R1213* cases had thrombocytopenia (baseline automated platelet counts, 63-147 × 109 L−1) and enlarged platelets (mean platelet volume, 11.2-14.1 fL), confirmed by light microscopy (Figure 3A; Table 1) and by morphometric analysis of platelet electron micrographs (Table 2). The platelet count ranges in the male and female cases corresponded to the percentile ranges 0.15 to 2.81 and 0.08 to 0.38, respectively, of a sex-stratified population of 443 142 UK BioBank volunteers. For mean platelet volume, the corresponding percentiles were 99.81 to 99.83 and 94.14 to 99.92 (supplemental Figure 3). Asymptomatic mild neutropenia was observed on at least 1 occasion in 6 cases (range of neutrophil counts, 0.62-4.34 × 109 L−1) but varied within the cases at different times (Table 1). Four cases displayed iron deficiency anemia, which corrected completely with dietary iron supplementation. The other cases had no red cell abnormalities, suggesting that the erythroid lineage was unaltered by the DIAPH1 R1213* variant. Platelets from 3 tested cases showed normal aggregation with adenosine 5′-diphosphate (ADP; 2.5-10 μM), collagen (2 μg mL−1), arachidonic acid (0.5 mg mL−1), thrombin receptor–activating peptide 14-mer (TRAP; 50 μM), and ristocetin (0.5, 1, and 5 mg mL−1). Dense-granule secretion stimulated by ADP and TRAP (cases 10, 16, 17, and 21) as well as α-granule secretion (cases 10 and 16) were unchanged compared with controls. Platelet surface expression of αIIbβ3 integrin and glycoprotein Ib-IX-V (cases 10, 16, and 17) was slightly increased compared with controls, consistent with the increased platelet size. Electron microscopy (cases 10, 16, 17, and 21) showed that the enlarged platelets were typically round, although occasionally highly elongated. There were also abnormal vacuoles, membrane complexes, and abnormally distributed α-granules, some of which were unusually large (Figure 3B-F). Using electron microscopy, we have quantified the surface, maximal, and minimal diameters of platelets on sections, which confirmed the increased platelet size (Table 2). Only for case 10 was the concentration of granules significantly increased (Table 2). Electron micrographs of neutrophils from the DIAPH1 R1213* cases showed a heterogeneous content of granules but no abnormal cytoplasmic inclusions, as observed in some cases with MYH9-related disorder (MYH9-RD; supplemental Figure 4).

Effect of DIAPH1 R1213* variant on platelet morphology. Illustration of the typical platelet morphology for cases 10, 16, 17, and 21. (A) Arrows highlight platelets of different size (case 21). Original magnification, ×100; May-Grünwald-Giemsa stain. (B) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) revealed an abnormal large granule (LG) (case 21). (C) TEM image of control platelets shows they are discoid and of regular size and have homogeneously distributed granules. All examined platelets of the patients show a heterogeneous size, shape, and distribution of α granules. (D) TEM image of a very thin elongated platelet and other platelets with a more round shape with few granules (case 10). (E) TEM image illustrates a very round platelet with many granules (case 17). (F) TEM of platelets from case 16 revealed an abnormal presence of vacuoles (V) and a membrane complex (MC). Bars represent 1 μm. The TEM images were acquired using either an EM900 (Carl Zeiss) or a JEM-1010 (JEOL) transmission electron microscope.

Effect of DIAPH1 R1213* variant on platelet morphology. Illustration of the typical platelet morphology for cases 10, 16, 17, and 21. (A) Arrows highlight platelets of different size (case 21). Original magnification, ×100; May-Grünwald-Giemsa stain. (B) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) revealed an abnormal large granule (LG) (case 21). (C) TEM image of control platelets shows they are discoid and of regular size and have homogeneously distributed granules. All examined platelets of the patients show a heterogeneous size, shape, and distribution of α granules. (D) TEM image of a very thin elongated platelet and other platelets with a more round shape with few granules (case 10). (E) TEM image illustrates a very round platelet with many granules (case 17). (F) TEM of platelets from case 16 revealed an abnormal presence of vacuoles (V) and a membrane complex (MC). Bars represent 1 μm. The TEM images were acquired using either an EM900 (Carl Zeiss) or a JEM-1010 (JEOL) transmission electron microscope.

Characteristics of 8 cases with the DIAPH1 R1213* variant

| . | Pedigree 1 cases . | Pedigree 2 cases . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 . | 14 . | 15 . | 16 . | 17 . | 21 . | 22 . | 24 . | |

| Gender | Male | Female | Male | Female | Female | Female | Male | Male |

| Year of birtd in 5-y bins | 1951-1955 | 1976-1980 | 1976-1980 | 1981-1985 | 1976-1980 | 1976-1980 | 2001-2005 | 2006-2010 |

| Platelet count, ×109 L−1 | 69-110* | 97* | 140-147* | 66-114* | 94-107* | 63-115* | 116-129* | 93-102* |

| Mean platelet volume, fL | 13.6* | 11.2* | 13.5* | 13.1-14.1* | 12.1* | 13.2* | 12.9* | 13.2* |

| Neutrophil count, ×109 L−1 | 1.21* | 1.49† | 1.66† | 3.11-3.74 | 0.9-2.27† | 1.29-4.34† | 0.64-1.84† | 0.62-1.02† |

| Hemoglobin, g dL−1 | 13.2-14.1 | 12.7 | 15 | 12.3-12.5 | 10.9-12.4† | 10.2-12.6† | 11.2-11.9† | 10.4-11.1† |

| Bleeding score‡ | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Type of hearing loss | HFSN | HFSN | HFSN, C | HFSN | HFSN | HFSN | HFSN | HFSN |

| Age of hearing loss, y | 8 | 2 | 8 | 6 | 6 | Not known | 2 | 1 |

| . | Pedigree 1 cases . | Pedigree 2 cases . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 . | 14 . | 15 . | 16 . | 17 . | 21 . | 22 . | 24 . | |

| Gender | Male | Female | Male | Female | Female | Female | Male | Male |

| Year of birtd in 5-y bins | 1951-1955 | 1976-1980 | 1976-1980 | 1981-1985 | 1976-1980 | 1976-1980 | 2001-2005 | 2006-2010 |

| Platelet count, ×109 L−1 | 69-110* | 97* | 140-147* | 66-114* | 94-107* | 63-115* | 116-129* | 93-102* |

| Mean platelet volume, fL | 13.6* | 11.2* | 13.5* | 13.1-14.1* | 12.1* | 13.2* | 12.9* | 13.2* |

| Neutrophil count, ×109 L−1 | 1.21* | 1.49† | 1.66† | 3.11-3.74 | 0.9-2.27† | 1.29-4.34† | 0.64-1.84† | 0.62-1.02† |

| Hemoglobin, g dL−1 | 13.2-14.1 | 12.7 | 15 | 12.3-12.5 | 10.9-12.4† | 10.2-12.6† | 11.2-11.9† | 10.4-11.1† |

| Bleeding score‡ | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Type of hearing loss | HFSN | HFSN | HFSN, C | HFSN | HFSN | HFSN | HFSN | HFSN |

| Age of hearing loss, y | 8 | 2 | 8 | 6 | 6 | Not known | 2 | 1 |

Data from the hematologic tests are presented as the minimum and maximum values observed in all available results from the cases.

C, conductive; HFSN, high-frequency sensorineural.

Every observed test result value is outside laboratory reference interval.

Test result value (or at least 1 value in the range) is outside age- and sex-adjusted laboratory reference intervals.

Determined by using the International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis Bleeding Assessment Tool. Pathological bleeding is associated witd bleeding scores >4.

Quantitative morphometric evaluation of platelet size parameters and the number of α granules of cases 10, 16, and 17 and controls using electron microscopy

| Group (n*) . | Area, µm2 . | Maximal diameter, µm . | Minimal diameter, µm . | Platelets >4 µm2, % . | No. of α granules per square micrometer . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (862) | 2.53 ± 1.47 | 2.89 ± 0.67 | 1.09 ± 0.46 | 10.90 | 2.60 ± 0.1 |

| P10 (99) | 3.90 ± 2.50† | 3.17 ± 0.76† | 1.51 ± 0.73† | 31.26‡ | 3.23 ± 1.46† |

| P16 (107) | 6.84 ± 4.92† | 3.77 ± 0.96† | 2.14 ± 0.91† | 71.03‡ | 2.45 ± 0.95 |

| P17 (100) | 5.48 ± 3.30† | 3.64 ± 0.90† | 1.85 ± 0.81† | 49.00‡ | 2.46 ± 1.26 |

| Group (n*) . | Area, µm2 . | Maximal diameter, µm . | Minimal diameter, µm . | Platelets >4 µm2, % . | No. of α granules per square micrometer . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (862) | 2.53 ± 1.47 | 2.89 ± 0.67 | 1.09 ± 0.46 | 10.90 | 2.60 ± 0.1 |

| P10 (99) | 3.90 ± 2.50† | 3.17 ± 0.76† | 1.51 ± 0.73† | 31.26‡ | 3.23 ± 1.46† |

| P16 (107) | 6.84 ± 4.92† | 3.77 ± 0.96† | 2.14 ± 0.91† | 71.03‡ | 2.45 ± 0.95 |

| P17 (100) | 5.48 ± 3.30† | 3.64 ± 0.90† | 1.85 ± 0.81† | 49.00‡ | 2.46 ± 1.26 |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

Number of platelet sections examined.

P < .01 vs control by Student t test (P < .01 is considered significant).

P < .01 vs control by χ2 test.

Abnormal bleeding symptoms included menorrhagia and mild subcutaneous bleeding in case 17 and a postpartum bleed in case 21 but were absent in the other cases. The sensorineural hearing loss that segregated with MTP was detected either at birth or in the first decade of life but progressed rapidly to a severe defect requiring bilateral hearing aids in all 8 cases. None of the DIAPH1 R1213* cases had abnormal renal function or early-onset cataract.

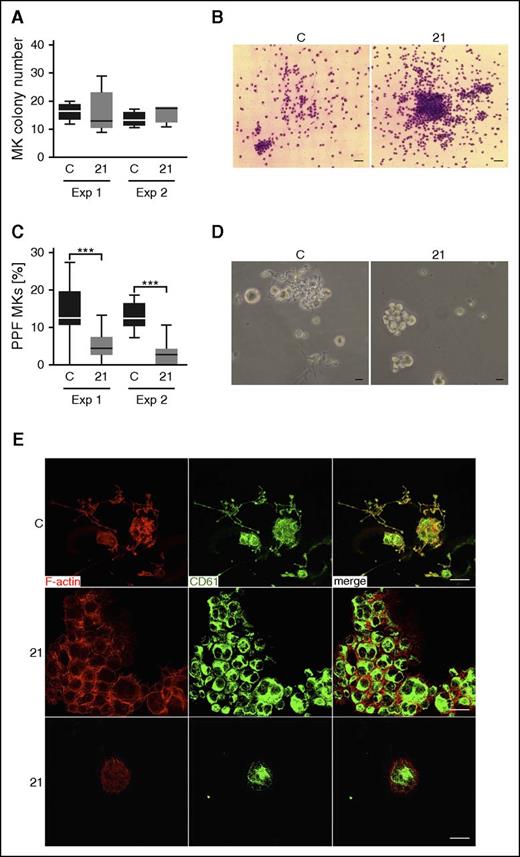

Abnormal maturation of DIAPH1 R1213* MKs

Assessment of MK proliferation, differentiation, and proplatelet formation of CD34+ stem cell–derived MKs from case 21 and controls on 2 separate occasions revealed similar numbers of CFU-MKs at day 12 of culture (Figure 4A). However, the MK colonies from case 21 had a higher cell density compared with controls (Figure 4B; supplemental Figure 5). Suspension cultures from case 21 showed a pronounced defect in proplatelet formation compared with different controls in 2 independent experiments (Figure 4C-D). In addition, we found numerous MK clusters containing small and large MKs (Figure 4D; supplemental Figure 6) in cultures from case 21 that were not present in control cultures, which hampered analysis of MK ploidy by flow cytometry (supplemental Figure 7).

Repeated MK proliferation, differentiation, and proplatelet-formation studies for a R1213* variant case. (A) Total amount of CFU-MK colonies derived from a total of 5000 peripheral blood CD34+ mononuclear cells per plate from a control and from case 21 (21) at day 12 of culture. This experiment (Exp) was repeated at 2 independent occasions (Exp 1 and Exp 2). (B) Representative images of cultured CFU-MK colonies from a control and from case 21 at day 12 of culture visualized by light microscopy after staining with May-Grünwald-Giemsa stain (Exp 2). Bars represent 50 μm. (C) MKs in triplicated liquid suspension cultures performed at 2 independent occasions were classified as proplatelet forming (PPF) MKs when proplatelet extensions were visible by light microscopy. The proportion of PPF MKs was lower in the cultures from case 21 compared with controls (1-way analysis of variance, ***P > .001). (D) Representative light microscopy images of cultured MKs showing formation of proplatelet extensions for the control. PPF MKs are almost absent for case 21, although they typically present in MK clusters that contain large and small cells. Bars represent 20 μm. (E) Immunofluorescence confocal microcopy images of differentiated fibrinogen-adhered MKs at day 12 of culture visualized by anti-integrin β3 (green; CD61) and phalloidin (red; F-actin) staining, showing colocalization in MKs from control, but not from case 21. Bars represent 20 μm. Numerous PPF MKs are present in the control (representative image), whereas MKs for case 21 form clusters. C, control.

Repeated MK proliferation, differentiation, and proplatelet-formation studies for a R1213* variant case. (A) Total amount of CFU-MK colonies derived from a total of 5000 peripheral blood CD34+ mononuclear cells per plate from a control and from case 21 (21) at day 12 of culture. This experiment (Exp) was repeated at 2 independent occasions (Exp 1 and Exp 2). (B) Representative images of cultured CFU-MK colonies from a control and from case 21 at day 12 of culture visualized by light microscopy after staining with May-Grünwald-Giemsa stain (Exp 2). Bars represent 50 μm. (C) MKs in triplicated liquid suspension cultures performed at 2 independent occasions were classified as proplatelet forming (PPF) MKs when proplatelet extensions were visible by light microscopy. The proportion of PPF MKs was lower in the cultures from case 21 compared with controls (1-way analysis of variance, ***P > .001). (D) Representative light microscopy images of cultured MKs showing formation of proplatelet extensions for the control. PPF MKs are almost absent for case 21, although they typically present in MK clusters that contain large and small cells. Bars represent 20 μm. (E) Immunofluorescence confocal microcopy images of differentiated fibrinogen-adhered MKs at day 12 of culture visualized by anti-integrin β3 (green; CD61) and phalloidin (red; F-actin) staining, showing colocalization in MKs from control, but not from case 21. Bars represent 20 μm. Numerous PPF MKs are present in the control (representative image), whereas MKs for case 21 form clusters. C, control.

Confocal microscopy of control MKs on day 12 of culture showed a partial colocalization of CD61 and F-actin, which was not observed in MKs from case 21 (Figure 4E). There was also aberrant architecture of the cortical F-actin cytoskeleton in MKs from case 21, as well as small filopodia-like protrusions and F-actin-positive junctions at the contact zones of clustered MKs (Figure 4E). This is in line with previous studies in which DIAPH1 was shown to regulate adherens junctions via the actin network.31,32

The R1213* variant is associated with altered DIAPH expression in platelets

We next investigated the effect of the R1213* variant on DIAPH1 expression in platelets by performing western blot analysis using an antibody recognizing the DIAPH1 amino terminus. In EDTA-anticoagulated platelet lysates from cases 10, 16, 17, and 21, normal expression levels of DIAPH1 were found, whereas in acid citrate dextrose–anticoagulated platelet lysates, the 155 kDa band corresponding to the full-length DIAPH1 protein was decreased in intensity compared with controls, and a band of ∼80 kDa was more intense (Figure 5A; supplemental Figures 8 and 9). The 80 kDa band did not correspond to any DIAPH1 transcripts listed in Ensembl but, after immunoprecipitation and mass spectrometry, was found to contain peptide sequences with 57% coverage across the full length of the DIAPH1 protein sequence (supplemental Proteomic Data). Moreover, this band was also immunoreactive with antibodies recognizing the DIAPH1 carboxyl terminus (supplemental Figure 8), suggesting that it resulted from limited proteolysis of DIAPH1 in platelets as reported previously.33 Because DIAPH1 expressed from the R1213* variant allele is predicted to have only a 60–amino acid truncation, it was not possible to resolve the relative contribution of the variant DIAPH1 to either of the immunoreactive bands (supplemental Figure 8B).

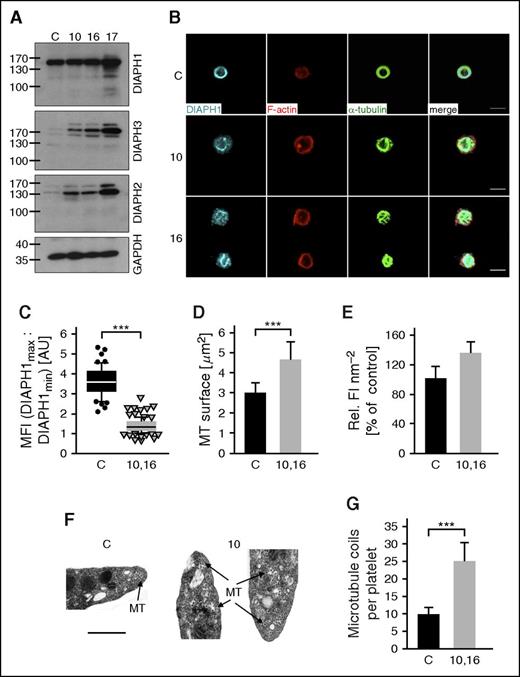

Altered expression of DIAPH1-3 and cytoskeletal organization in platelets from DIAPH1 R1213* variant cases. (A) Representative western blots of resolved platelet protein extracts from DIAPH1 R1213* cases 10, 16, and 17 and from a control probed with antibodies recognizing DIAPH1, DIAPH3, DIAPH2, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). Compared with the control, the DIAPH1 R1213* cases show normal expression of DIAPH1. The content of DIAPH2 and DIAPH3 is increased in the cases compared with control. Similar quantities of total protein in the western blot lanes are indicated by the control blot probed with an antibody recognizing GAPDH. (B) Representative confocal microscopy images of poly-l-lysine-immobilized resting platelets from cases 10 and 16 and from a control stained for DIAPH1 (cyan), F-actin (red), and α-tubulin (green). Platelets were visualized using a Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems). Bars represent 3 μm. (C) Image analysis (ratio of the mean of the first and last maxima and the mean of the first and last minima) revealed an aberrant distribution of DIAPH1 in platelets from cases 10 and 16 as compared with controls. Box plots display first and third quartiles, and whiskers mark minimum and maximum values unless exceeding 1.5 times the interquartile range of at least 50 platelets per group; symbols represent outliers, and the horizontal line displays the median. Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test, ***P < .001. (D-E) Quantification of the immunostained α-tubulin surface (D) and fluorescence intensity per surface unit of the F-actin staining (E) revealed an increased content and an abnormal distribution in platelets from the cases. Values represent means ± SD (n = 3 controls vs case 10 and 16; 100 platelets). Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test, ***P < .001. (F) Representative transmission electron micrographs showing that the microtubules (indicated by arrows) are disorganized and distributed throughout the cytoplasm of platelets from case 10 compared with controls in which microtubules are organized into the marginal band. Images were collected using an EM900 (Carl Zeiss) electron microscope. Bars represent 0.5 μm. (G) Manual counting of microtubules revealed an increased number of microtubules in platelets from the cases (n = 41 platelets) compared with controls (n = 104 platelets). Microtubule numbers per platelet are expressed as mean ± SD. Unpaired Student t test, ***P < .001. AU, arbitrary units; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; MT, microtubule; Rel. FI, relative fluorescence intensity; SD, standard deviation.

Altered expression of DIAPH1-3 and cytoskeletal organization in platelets from DIAPH1 R1213* variant cases. (A) Representative western blots of resolved platelet protein extracts from DIAPH1 R1213* cases 10, 16, and 17 and from a control probed with antibodies recognizing DIAPH1, DIAPH3, DIAPH2, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). Compared with the control, the DIAPH1 R1213* cases show normal expression of DIAPH1. The content of DIAPH2 and DIAPH3 is increased in the cases compared with control. Similar quantities of total protein in the western blot lanes are indicated by the control blot probed with an antibody recognizing GAPDH. (B) Representative confocal microscopy images of poly-l-lysine-immobilized resting platelets from cases 10 and 16 and from a control stained for DIAPH1 (cyan), F-actin (red), and α-tubulin (green). Platelets were visualized using a Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems). Bars represent 3 μm. (C) Image analysis (ratio of the mean of the first and last maxima and the mean of the first and last minima) revealed an aberrant distribution of DIAPH1 in platelets from cases 10 and 16 as compared with controls. Box plots display first and third quartiles, and whiskers mark minimum and maximum values unless exceeding 1.5 times the interquartile range of at least 50 platelets per group; symbols represent outliers, and the horizontal line displays the median. Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test, ***P < .001. (D-E) Quantification of the immunostained α-tubulin surface (D) and fluorescence intensity per surface unit of the F-actin staining (E) revealed an increased content and an abnormal distribution in platelets from the cases. Values represent means ± SD (n = 3 controls vs case 10 and 16; 100 platelets). Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test, ***P < .001. (F) Representative transmission electron micrographs showing that the microtubules (indicated by arrows) are disorganized and distributed throughout the cytoplasm of platelets from case 10 compared with controls in which microtubules are organized into the marginal band. Images were collected using an EM900 (Carl Zeiss) electron microscope. Bars represent 0.5 μm. (G) Manual counting of microtubules revealed an increased number of microtubules in platelets from the cases (n = 41 platelets) compared with controls (n = 104 platelets). Microtubule numbers per platelet are expressed as mean ± SD. Unpaired Student t test, ***P < .001. AU, arbitrary units; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; MT, microtubule; Rel. FI, relative fluorescence intensity; SD, standard deviation.

Western blots generated from platelets from the DIAPH1 R1213* cases also showed increased DIAPH2 and DIAPH3 expression compared with controls (Figure 5A). Expression of DIAPH2 and DIAPH3 has previously been observed to decrease during MK maturation,17 which we confirmed by RNA sequencing analysis (supplemental Figure 10). Therefore, our observations in the DIAPH1 R1213* cases are consistent with platelet formation from MKs with deregulated maturation and support the previous observations in MKs from bone marrow and culture (Figure 4A-B).17

DIAPH1 R1213* and altered platelet cytoskeleton

Using confocal microscopy, we found that DIAPH1 was localized to the peripheral marginal band in resting platelets from controls but was distributed throughout the cytoplasm of platelets from DIAPH1 R1213* cases 10 and 16 (Figure 5B-C). There was also increased F-actin and α-tubulin staining and aberrant organization of microtubules compared with controls (Figure 5B-E). Electron microscopy confirmed microtubule disorganization (Figure 5F), and quantification by manual counting revealed ∼2.6-fold more microtubule coils in platelets from the DIAPH1 R1213* cases compared with controls (Figure 5G). Incubation of platelets from controls at 4°C caused disassembly of microtubules, which then reassembled to the marginal band after rewarming to 37°C, as previously reported.22-24 In contrast, cold incubation or rewarming did not grossly affect the microtubules in platelets from the DIAPH1 R1213* cases (Figure 6A-B), suggesting that the increased microtubule content resulted from increased microtubule stability.

Increased microtubule stability in platelets from DIAPH1 R1213* cases. (A-C) Representative confocal microscopy images (A,C) and quantification of the microtubule surface (B) of platelets from DIAPH1 R1213* cases 10 and 16 and from a control after incubation at 4°C (A-B) or after treatment with the microtubule destabilizing toxin colchicine (10 μM; B-C). F-actin is displayed as red; posttranslationally modified α-tubulin (ac-tub and Glu-tub) as green. Values are expressed as means ± SD (n = 3 controls [black] vs case 10 and 16 [gray]; 100 platelets). Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test, ***P < .001. (D) Representative confocal microscopy images of platelets after spreading on fibrinogen (2.5 μg cm−2). F-actin is displayed as red; α-tubulin, ac-tub, and Glu-tub as green. Platelets in panels A, C, and D were visualized using a Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems). Bars represent 3 μm. (E) Quantification of the fluorescence intensity per surface unit of the immunostaining for F-actin and posttranslational modifications on α-tubulin. Values are expressed as means ± SD (n = 3 controls vs cases 10 and 16; 100 platelets). Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test, ***P < .001. (F) Western blots of the platelet microtubule cytoskeleton in total protein extract and in pellet or soluble fractions from a healthy control and from cases 10 and 16 separated by ultracentrifugation and probed with antibodies recognizing Tyr-tub, ac-tub, or Glu-tub. Data are presented from resting platelets and after treatment with 10 μM colchicine. Equivalent quantities of total platelet extract protein were loaded in each lane. (G-H) Densitometric analyses of the immunoblots. The data are expressed as the means ± SD of the ratios of the stable microtubule markers ac-tub (G) and Glu-tub (H) to the content of the dynamic microtubule marker Tyr-tub (n = 3 blots). Unpaired Student t test, *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001. colch, 10 μM colchicine–treated platelets; α-tubulin, α-tub; F-act, F-actin; NS, nonsignificant; rest, resting platelets; P, pellet tubulin fraction; S, soluble tubulin fraction; T, total protein extract.

Increased microtubule stability in platelets from DIAPH1 R1213* cases. (A-C) Representative confocal microscopy images (A,C) and quantification of the microtubule surface (B) of platelets from DIAPH1 R1213* cases 10 and 16 and from a control after incubation at 4°C (A-B) or after treatment with the microtubule destabilizing toxin colchicine (10 μM; B-C). F-actin is displayed as red; posttranslationally modified α-tubulin (ac-tub and Glu-tub) as green. Values are expressed as means ± SD (n = 3 controls [black] vs case 10 and 16 [gray]; 100 platelets). Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test, ***P < .001. (D) Representative confocal microscopy images of platelets after spreading on fibrinogen (2.5 μg cm−2). F-actin is displayed as red; α-tubulin, ac-tub, and Glu-tub as green. Platelets in panels A, C, and D were visualized using a Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems). Bars represent 3 μm. (E) Quantification of the fluorescence intensity per surface unit of the immunostaining for F-actin and posttranslational modifications on α-tubulin. Values are expressed as means ± SD (n = 3 controls vs cases 10 and 16; 100 platelets). Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test, ***P < .001. (F) Western blots of the platelet microtubule cytoskeleton in total protein extract and in pellet or soluble fractions from a healthy control and from cases 10 and 16 separated by ultracentrifugation and probed with antibodies recognizing Tyr-tub, ac-tub, or Glu-tub. Data are presented from resting platelets and after treatment with 10 μM colchicine. Equivalent quantities of total platelet extract protein were loaded in each lane. (G-H) Densitometric analyses of the immunoblots. The data are expressed as the means ± SD of the ratios of the stable microtubule markers ac-tub (G) and Glu-tub (H) to the content of the dynamic microtubule marker Tyr-tub (n = 3 blots). Unpaired Student t test, *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001. colch, 10 μM colchicine–treated platelets; α-tubulin, α-tub; F-act, F-actin; NS, nonsignificant; rest, resting platelets; P, pellet tubulin fraction; S, soluble tubulin fraction; T, total protein extract.

The formation of stable microtubules is associated with posttranslational detyrosination (Glu-tub) and acetylation (ac-tub) of α-tubulin, whereas dynamic microtubules are characterized by tyrosinated α-tubulin (Tyr-tub).34,35 After treatment with colchicine or cold incubation to destabilize microtubules, platelets from DIAPH1 R1213* cases 10 and 16 showed a higher content of stable detyrosinated and acetylated microtubules compared with controls (Figure 6A-C; supplemental Figure 11). During spreading on fibrinogen, platelets from the DIAPH1 R1213* cases maintained detyrosinated and acetylated microtubules, whereas these modifications were rarely detected in controls (Figure 6D-E). Platelets from the DIAPH1 R1213* cases also displayed an increased content and aberrant organization of F-actin, particularly at the platelet cortex where there was increased formation of small filopods (Figure 6D-E). Fractionation of the tubulin cytoskeleton by ultracentrifugation revealed higher ac-tub/Tyr-tub and Glu-tub/Tyr-tub band-density ratios in the DIAPH1 R1213* cases compared with controls, particularly in the polymerized (pellet) microtubule fraction, confirming a higher content of stable microtubules (Figure 6F-H).

DIAPH1 R1213* alters cytoskeletal organization in cell lines

In HEK293FT cells transfected with wild-type (DIAPH1 WT) or variant (DIAPH1 R1213*) expression constructs, western blots confirmed overexpression of both DIAPH1 WT and DIAPH1 R1213* proteins. However, in contrast to platelets from the DIAPH1 R1213* cases, expression of DIAPH2 or DIAPH3 was not increased, allowing us to study the effect of the truncated DIAPH1 R1213* variant in isolation (Figure 7A). Transfection of the human adenocarcinoma lung (A549) epithelial cell line with both expression constructs increased the prevalence of F-actin, microtubules, and acetylated microtubules compared with adjacent untransfected cells. This effect was more pronounced in DIAPH1 R1213* than in DIAPH1 WT cells (Figure 7B-D; supplemental Figure 12).

Overexpression of DIAPH1 R1213* in cell lines reproduces the cytoskeletal alterations in platelets. (A) Western blot of protein extracts from HEK293FT cells transfected with DIAPH1 WT (WT), DIAPH1 R1213* (R1213*), or empty (C) expression constructs, probed with antibodies recognizing the DIAPH1 amino terminus, DIAPH3, or DIAPH2. Confocal microscopy images of A549 cells transiently transfected with the DIAPH1 WT or R1213* expression constructs were stained for F-actin (red), α-tubulin (green), and DIAPH1 (cyan) (B) and for F-actin (red), ac-tub (green), and DIAPH1 (cyan) (C) and with DAPI nuclear counterstain (blue) (B-C). (D) Quantification of the relative fluorescence intensity per surface unit of transfected and nontransfected cells revealed an increased content of F-actin, α-tubulin, and ac-tub in the cells overexpressing DIAPH1 R1213* compared with adjacent nontransfected cells (differences are indicated by asterisks) and DIAPH1 WT–overexpressing cells (differences are indicated by pound signs). (E-F) Incubation with the FH2 domain inhibitor SMIFH2 reduced F-actin content, but not the content of microtubules and ac-tub as determined by quantification of the relative fluorescence intensity per surface unit. Values in panels D and F are expressed as means ± SD (n = 100 cells). Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test, **,##P < .01; ***,###P < .001. The cells in panels B, C, and E were visualized using a Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems). Bars represent 10 μm.

Overexpression of DIAPH1 R1213* in cell lines reproduces the cytoskeletal alterations in platelets. (A) Western blot of protein extracts from HEK293FT cells transfected with DIAPH1 WT (WT), DIAPH1 R1213* (R1213*), or empty (C) expression constructs, probed with antibodies recognizing the DIAPH1 amino terminus, DIAPH3, or DIAPH2. Confocal microscopy images of A549 cells transiently transfected with the DIAPH1 WT or R1213* expression constructs were stained for F-actin (red), α-tubulin (green), and DIAPH1 (cyan) (B) and for F-actin (red), ac-tub (green), and DIAPH1 (cyan) (C) and with DAPI nuclear counterstain (blue) (B-C). (D) Quantification of the relative fluorescence intensity per surface unit of transfected and nontransfected cells revealed an increased content of F-actin, α-tubulin, and ac-tub in the cells overexpressing DIAPH1 R1213* compared with adjacent nontransfected cells (differences are indicated by asterisks) and DIAPH1 WT–overexpressing cells (differences are indicated by pound signs). (E-F) Incubation with the FH2 domain inhibitor SMIFH2 reduced F-actin content, but not the content of microtubules and ac-tub as determined by quantification of the relative fluorescence intensity per surface unit. Values in panels D and F are expressed as means ± SD (n = 100 cells). Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test, **,##P < .01; ***,###P < .001. The cells in panels B, C, and E were visualized using a Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems). Bars represent 10 μm.

Western blot analysis of microtubule fractions showed that DIAPH1 R1213*–transfected HEK293FT cells had a higher content of acetylated and detyrosinated microtubules in the polymerized tubulin fraction compared with DIAPH1 WT or mock-transfected controls (supplemental Figure 12), thereby reproducing the cytoskeletal alterations found in platelets from the cases. Incubation of the cells with the small-molecule FH2-domain inhibitor SMIFH2 did not influence expression of DIAPH1, -2, or -3 (Figure 7A) and did not prevent stabilization of microtubules by DIAPH1 R1213* (Figure 7E-F). However, SMIFH2 did reduce the increase in F-actin content in cells overexpressing DIAPH1 R1213* (Figure 7E-F), confirming that the DIAPH1 FH2 domain is critical for the F-actin polymerization.

Discussion

We have identified DIAPH1 as a novel candidate gene for dominant MTP and sensorineural hearing loss by analysis of the largest ever assembled collection of cases with previously uncharacterized BPD. Essential to this discovery was the annotation of the characteristics of the cases with HPO terms for hematologic features and phenotypes in other organ systems, and then statistical analysis to identify similarities in HPO terms between cases. We have previously shown that cluster analysis of HPO terms within a large BPD case collection enabled identification of causal variants in ACTN1 and MYH9 that have been associated with MTP.7,9 However, the statistical evidence supporting DIAPH1 as a candidate gene could only be obtained by applying a novel similarity regression method to the phenotype and genotype data.19 Specifically, similarity regression revealed a hitherto unidentified association between a characteristic phenotype that was ontologically similar for 2 unrelated index cases and the shared presence of a high-impact variant in DIAPH1. We also showed that the high-impact variant in DIAPH1 was the same premature stop variant R1213* in both index cases and that this segregated with MTP and sensorineural hearing loss in a further 6 pedigree members, thereby confirming linkage with R1213*.

It is noteworthy that DIAPH1 has been identified previously as the candidate gene for nonsyndromic sensorineural deafness type “Deafness, Autosomal Dominant 1” (DFNA1) (ORPHA90635) in a single characterized pedigree, in which hearing loss typically developed later in childhood than in the DIAPH1 R1213* cases.36,37 The causal variant for DFNA1 caused aberrant splicing of DIAPH1 in lymphocyte cDNA that predicted expression of DIAPH1 with an abnormal carboxyl terminus sequence from glutamine 1220, and chain truncation after a further 21 amino acids.36 No platelet count or volume data are reported for the DFNA1 pedigree, preventing a direct comparison with the DIAPH1 R1213* pedigrees reported here. However, an important difference is that the DFNA1 variant disrupts only the 2 final residues in the DIAPH1 DAD domain (1194-1222 in UNIPROT O60610), which in contrast to R1213* does not result in loss of the autoregulatory basic RRKR motif. Absent expression of DIAPH1 resulting from a homozygous stop-gain variant at codon 778 has been associated previously with short stature, microcephaly, and visual impairment without reported hearing or hematologic phenotypes.38 These observations suggest that genetic abnormalities of DIAPH1 may be associated with a range of phenotypes that together constitute a novel group of DIAPH1-RD.

MTP and hearing loss may also cosegregate in MYH9-RD (ORPHA182050) in which abnormal expression of nonmuscle myosin heavy-chain IIA alters myosin-dependent organelle distribution and F-actin organization, thereby disrupting MK proplatelet formation.13,14 Aberrant cytoskeletal organization in inner ear stereocilia has been proposed as a mechanism for hearing loss in MYH9-RD16 and may contribute to this phenotype in the DIAPH1 R1213* cases. However, there are also several characteristics of the DIAPH1 R1213* cases that are absent in MYH9-RD. For example, platelets in the DIAPH1 R1213* cases were elongated or round, moderately enlarged, and contained few membrane complexes, whereas in MYH9-RD, platelets are highly enlarged and contain abundant membrane complexes. Hearing loss was early onset and severe in the DIAPH1 R1213* cases but develops in only 35% of MYH9-RD cases, typically after 10 years of age.10 Cataract and nephropathy are reported in 5% and 21% of MYH9-RD cases, respectively,10 but were absent in the DIAPH1 R1213* cases. Interestingly, mild neutropenia was frequently observed in the DIAPH1 R1213* cases (Table 1). These observations indicate that DIAPH1 R1213* should be regarded as distinct from MYH9-RD.

DIAPH1 is a conserved member of the formin protein family, which mediates Rho GTPase–dependent assembly of F-actin and microtubule regulation during cytoskeletal remodeling in cytokinesis, organelle trafficking, and filopodia formation. Several mammalian formins mediate cell differentiation and adhesive events required for hematopoiesis.25,39 However, a critical negative regulatory role for DIAPH1 is indicated by the observations that targeted knockout of the murine DIAPH1 ortholog Drf1 resulted in hyperproliferative myelodysplasia.40,41 Consistent with this, DIAPH1 knockdown in cultured human MKs resulted in increased proplatelet formation.17 In contrast, overexpression of a constitutively active DIAPH1, in which both the DID and DAD were deleted by artificial mutagenesis (mDiaΔN3), reduced proplatelet formation in cultured human MKs.17 We also observed reduced proplatelet formation in CD34+ cell–derived MKs from DIAPH1 R1213* case 21, suggesting that this variant may also result in constitutive activation of DIAPH1. The MK culture experiments also suggested that the DIAPH1 R1213* variant was associated with enhanced MK proliferation because an increased number of cells were present in the separate CFU-MK colonies from case 21. As a consequence of the increased cell density in the CFU-MK colonies, we were unable to confirm this by counting the total number of single MKs. However, ploidy analysis of suspension cultures revealed no obvious differences in MK endomitosis because both large and small MKs were present in cultures from case 21. Further studies are required to evaluate the possibility of a hyperproliferative effect of early MKs due to the DIAPH1 R1213* variant.

The hypothesis that the DIAPH1 R1213* variant results in constitutively active DIAPH1 is also supported by the prediction that R1213* causes a partial truncation of the DIAPH1 DAD. Mutagenesis of the DAD has been shown previously to increase the formation of stable microtubule networks and F-actin bundles in cell models,42,43 consistent with loss of the DID interaction. This interaction is mediated in part by a DAD core MDxLLExL motif, which is unaffected by the DIAPH1 R1213* variant, and by the DAD basic RRKR motif, which is absent in the DIAPH1 R1213* variant.30 This second site of DID-DAD interaction is necessary for complete autoregulation of DIAPH1 because selective mutagenesis of the basic RRKR motif also conferred constitutive activity to DIAPH1 orthologs, resulting in abnormal F-actin polymerization and altered cell architecture.43,44

We provided experimental support for constitutive activation of DIAPH1 by showing disorganization of actin filaments and increased stability and content of microtubules in platelets from the DIAPH1 R1213* cases. Overexpression of DIAPH1 R1213* also resulted in increased assembly of actin filaments and stabilization of microtubules in cell lines, thereby reproducing the cytoskeletal alterations observed in platelets from the DIAPH1 R1213* cases. These effects on cytoskeletal organization may account directly for the reduced proplatelet formation from MKs derived from the cases, because highly regulated microtubule and F-actin dynamics are necessary for proplatelet extension and branching.4,45,46 It is noteworthy that overexpression of the constitutively active DIAPH1 mDiaΔN3, which reduced proplatelet formation in cultured human MKs, was shown previously to increase polymerization of F-actin, similar to that observed with the DIAPH1 R1213* variant. However, in MKs overexpressing mDiaΔN3, microtubule stability was reduced, showing that the cytoskeletal alterations do not completely reproduce those associated with the R1213* variant.17 One possible explanation for this difference is that in contrast to DIAPH1 R1213*, the mDiaΔN3 model additionally carries an N-terminal deletion, including the Rho GTPase–binding domain of DIAPH1, potentially causing a different effect of DIAPH1 regulation.17,43

The gain-of-function DIAPH1 R1213* variant represents a new human dominant syndromic disorder of MTP and sensorineural hearing loss that has different characteristics than DIAPH1 gene–deletion models. The platelet phenotype of the R1213* variant cases highlights the impact of abnormal regulation of DIAPH1 on cytoskeletal organization during platelet production.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted using full blood count data from the UK Biobank Resource. The authors thank Xavier Pillois and Line Pourtau from the Institut Hospitalo-Universitaire–L'Institut de Rythmologie et modélisation Cardiaque, Pessac, France, for their help in the preparation of DNA samples and platelet samples, respectively; Stephanie Burger-Stritt for assistance with blood withdrawals; Stephanie Lamer and Andreas Schlosser for their assistance with mass spectrometry and the microscopy platform of the Rudolf Virchow Center; Jean-Claude Bordet from the Reference Center for Platelet Disease, Lyon, France, for help in quantifying platelet granules and for electron microscopy; and the many colleagues and their patients who have made the BRIDGE-BPD study possible.

The NIHR BioResource–Rare Diseases and the associated BRIDGE genome sequencing projects are supported by the NIHR (http://www.nihr.ac.uk). This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB 688) (B.N.); a grant from the German Excellence Initiative to the Graduate School of Life Sciences, University of Würzburg (S. Stritt); the NIHR BioResource–Rare Diseases (E.T., D.G., J.C.S., S.P., I.S., C.J.P., R.M., S. Ashford, S.T., and K.S.); the Fund for Scientific Research-Flanders (FWO-Vlaanderen, Belgium, G.0B17.13N) and the Research Council of the University of Leuven (Bijzonder Onderzoeksfonds KU Leuven, Belgium, OT/14/098) (K.F., C.T., and C.v.G.); the Cancer Council Western Australia (W.N.E.); program grants from the European Commission, NIHR (RP-PG-0310-1002) and the National Health Service Blood and Transplant (NHSBT) (W.J.A., S. Maiwald, M.K., R.P., S.B.J., and W.H.O.); Medical Research Council Clinical Training Fellowships (MR/K023489/1) (C.L. and S.K.W.); a British Society of Haematology/NHSBT grant (T.K.B.); the Imperial College London Biomedical Research Centre (M.A.L. and C.L.); the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre (J.R.B.); the Medical Research Council and Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre (S.R.); the Bayer and Norbert Heimburger (CSL Behring) Chairs (C.v.G.); and the NIHR Bristol Cardiovascular Biomedical Research Unit (A.D.M.).

Authorship

Contribution: P.N. initiated the collaboration of the French Reference Center on Inherited Platelet Disorders, established the joint working with the BRIDGE-BPD Consortium, enrolled cases, and designed and performed experiments; S. Marlin provided expert advice on the observed hearing disorder in the cases; S. Stritt designed and performed experiments and was supervised by A.T.N., B.N., and P.N.; A.D.M. enrolled cases, collected phenotype data, and with K.F., designed and oversaw experiments by S.K.W. and C.T.; W.N.E. reviewed blood films and provided expert bone marrow pathology interpretation; W.H.O. and F.L.R. direct the NIHR BioResource–Rare Diseases and oversee with K.S. the DNA handling (J.C.S. and R.M.) and genome sequencing (analysis by C.J.P., S.T., and A.R.), whole exome sequencing (by I.S.), and whole genome sequencing (Illumina Cambridge Ltd); S. Ashford provided ethics support and NIHR BioResource–Rare Diseases study management; J.R.B. established and directs the NIHR BioResource, a collaborative network for enrolment across England; W.H.O. established and directs with M.A.L. and C.v.G. the BRIDGE-BPD Consortium and supervised with S.R. the genetic analysis by E.T. (chief analyst) and D.G., who developed and applied the similarity regression model, performed statistical analysis, and assisted with manuscript preparation; W.J.A. analyzed the full blood count data from the UK BioBank cohort; S.B.J. performed the experiments underlying the sequencing of RNA from immature (CD42b−) and mature (CD42b+) MKs; R.P., who was supervised by M.K., analyzed RNA sequencing data; S. Maiwald performed experiments on the DIAPH1 transcripts; S.K.W., C.L., T.K.B., A.M.K., T.B., P.C., R.F., M.P.L., M.M., C.M.M., D.J.P., S. Austin, S. Schulman, other members of the BRIDGE-BPD Consortium, K.G., P.N., and C.v.G. enrolled cases and collected phenotype data; J.C.S. encoded the pedigrees; S.P. was the study coordinator, provided ethics support, and assisted with manuscript preparation; and P.N., S.S., E.T., D.G., K.F., B.N., A.T.N., W.H.O., and A.D.M. cowrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

A list of additional members of the BRIDGE-BPD Consortium appears in the online data supplement.

Correspondence: Ernest Turro, Department of Haematology, University of Cambridge, and National Health Service Blood and Transplant, Long Rd, Cambridge CB2 0PT, United Kingdom; e-mail: et341@cam.ac.uk; and Kathleen Freson, Department of Cardiovascular Sciences, Center for Molecular and Vascular Biology, University of Leuven, Gasthuisberg O&N1, Herestraat 49- box 911, 3000 Leuven, Belgium; e-mail: kathleen.freson@med.kuleuven.be.

References

Author notes

S. Stritt, P.N., and E.T. contributed equally to this study.

K.F., W.H.O., and A.D.M. contributed equally to this study.

![Figure 6. Increased microtubule stability in platelets from DIAPH1 R1213* cases. (A-C) Representative confocal microscopy images (A,C) and quantification of the microtubule surface (B) of platelets from DIAPH1 R1213* cases 10 and 16 and from a control after incubation at 4°C (A-B) or after treatment with the microtubule destabilizing toxin colchicine (10 μM; B-C). F-actin is displayed as red; posttranslationally modified α-tubulin (ac-tub and Glu-tub) as green. Values are expressed as means ± SD (n = 3 controls [black] vs case 10 and 16 [gray]; 100 platelets). Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test, ***P < .001. (D) Representative confocal microscopy images of platelets after spreading on fibrinogen (2.5 μg cm−2). F-actin is displayed as red; α-tubulin, ac-tub, and Glu-tub as green. Platelets in panels A, C, and D were visualized using a Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems). Bars represent 3 μm. (E) Quantification of the fluorescence intensity per surface unit of the immunostaining for F-actin and posttranslational modifications on α-tubulin. Values are expressed as means ± SD (n = 3 controls vs cases 10 and 16; 100 platelets). Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test, ***P < .001. (F) Western blots of the platelet microtubule cytoskeleton in total protein extract and in pellet or soluble fractions from a healthy control and from cases 10 and 16 separated by ultracentrifugation and probed with antibodies recognizing Tyr-tub, ac-tub, or Glu-tub. Data are presented from resting platelets and after treatment with 10 μM colchicine. Equivalent quantities of total platelet extract protein were loaded in each lane. (G-H) Densitometric analyses of the immunoblots. The data are expressed as the means ± SD of the ratios of the stable microtubule markers ac-tub (G) and Glu-tub (H) to the content of the dynamic microtubule marker Tyr-tub (n = 3 blots). Unpaired Student t test, *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001. colch, 10 μM colchicine–treated platelets; α-tubulin, α-tub; F-act, F-actin; NS, nonsignificant; rest, resting platelets; P, pellet tubulin fraction; S, soluble tubulin fraction; T, total protein extract.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/127/23/10.1182_blood-2015-10-675629/4/m_2903f6.jpeg?Expires=1767697785&Signature=N-jTnBS0zVzCFxgI7w3q2fkS9wixUisvV2UrUXwV2FpJboS4rcygwNYrt85KI5GTDTh0REOchI8R1N-CLlKrW-HteaMWhCKRsf0UW7hyNQVteBp42j8rhypraaejMlqmG~cppBgt-3PboAptwy9B4JPLFrnVA2oqURzERd1~vkw8u5C~OWJf5LE7X2nsczCHQbT7tLCXfzKUTgk3dgX~LpxW2o4NIAoEtlPTCVnKNQwArlqAGJvHigFuRoiskpU2TUbNFU2rkBME~po~vtpC7PFO4kdu6dxM4RZUAMr4d~lhE8fbyTsEi0rTnO-XeqQS1NE4x4TVgK6W6mxV3Jz7LA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)