Abstract

Nodal marginal zone lymphoma (NMZL) is a rare form of indolent small B-cell lymphoma which has only been clearly identified in the last 2 decades and which to date remains incurable. Progress in therapeutic management has been slow, largely due to the very small number of patients treated and the heterogeneity of treatments administered; thus, standard-of-care treatment is currently nonspecific for this lymphoma entity. In this review, treatments routinely used to manage adult NMZL patients are presented, principally based on immunochemotherapy (when treatment is needed). Biological research behind the key axes of agents currently under development is described; development of novel agents is heavily based on data from gene profiling and genome-wide sequencing research, uncovering a number of critical deregulated pathways specific to NMZL tumors. These include B-cell receptor, JAK/STAT, NF-κB, NOTCH, and Toll-like receptor signaling pathways, as well as intracellular processes such as the cell cycle, chromatin remodeling, and transcriptional regulation in terms of epigenetic modifiers, histones, or transcriptional co-repressors, along with immune escape via T-cell–mediated tumor surveillance. These pathways are examined in detail and a projection of how the field may evolve in the near future for an efficient personalized treatment approach for NMZL patients is presented.

Introduction

Nodal marginal zone lymphomas (NMZLs) represent 1 of 3 recognized entities within the category of marginal zone lymphomas (MZLs), along with splenic marginal zone lymphomas (SMZLs) and extranodal marginal zone lymphomas, with the latter tumors also known as mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas. NMZLs, SMZLs, and MALT all belong to the category of indolent small B-cell lymphomas.1,2 NMZL is a distinct primary nodal B-cell lymphoma recognized as having morphologic and immunophenotypic similarities with SMZL and MALT lymphomas,3 but displays differences in terms of clinical presentation, molecular findings, treatment, and prognosis.

Historically, different terminologies have been used to describe NMZL, reflecting the difficulty in recognizing it and understanding its biological and clinical characteristics. It was first described by Sheibani et al in 1986 and termed “monocytoid B-cell lymphoma” taking its name from the predominant morphology of neoplastic cells resembling monocytes.4 Cousar et al then identified NMZL as a “parafollicular B-cell lymphoma,”5 while Piris et al reported a relationship to marginal zone cells.6 In 1990, the revised Kiel classification included the provisional entity “nodal monocytoid B-cell lymphoma,” which was renamed in 1994 in the Revised European-American Classification of Lymphoid Neoplasms (REAL) as “nodal marginal zone lymphoma with or without monocytoid B-cells.”7 NMZL was ultimately included as 1 of 3 MZL types in the 2001 and 2008 World Health Organization (WHO) classifications.1,8

Here, we review current management of NMZL patients, present the most recent preclinical research and active therapeutic developments in NMZL offering new insights into managing this incurable disease, and finally describe emerging therapeutics currently under evaluation and novel therapeutic areas being developed.

Epidemiology and clinical presentation

NMZL is a rare lymphoma subtype constituting <2% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas and ∼10% of MZLs. In a recent Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database, annual incidence of NMZL was 0.83 per 100 000 adults, and is even rarer in childhood.9 Incidence has increased by 41% since 2001,10 although this apparent increase is likely to reflect improved and more accurate recognition of this entity in recent years.

Given the rarity of this disease, descriptions of clinical features of NMZL are based on very few reports with relatively small numbers of patients.11-20 Clinically, NMZL has the same presentation as other indolent nodal lymphomas such as small lymphocytic lymphoma and follicular lymphoma.21 The vast majority of patients present with disseminated peripheral, abdominal, and thoracic nodal involvement, and disease is usually nonbulky. Diagnosis requires the exclusion of extranodal and splenic involvement so as to distinguish it from other MZL entities. Median age at diagnosis ranges from 50 to 64 years and the sex ratio differs between publications. Patients generally have a good performance status at diagnosis and no B symptoms. Bone marrow involvement is observed in approximately one-third of patients whereas peripheral blood involvement is rare, as is cytopenia.

Evidence exists supporting an association between NMZL and the hepatitis C virus (HCV; at least in geographic regions where high incidence of HCV has been reported22-25 ) and with chronic inflammation (but rarely with autoimmunity, which is in contrast with the other MZL entities where autoimmunity is frequently present). Cryoglobulin may be present when associated with HCV infection. Serum immunoglobulin M (IgM) paraprotein is detected infrequently (10% of patients).

Cellular origin

Hints as to the cellular origin of lymphoid B-cell tumors have been obtained by analysis of the immunoglobulin gene repertoire. Due to the relative rarity of NMZL, the small number of cases in initial reports has limited interpretation of these data.26-28 Further larger studies provided discordant results,29-31 showing either predominant involvement of IGVH4 genes, and more specifically the IGHV4-34 gene (30%), with most cases displaying hypersomatic mutations (HSMs) often with signs of antigenic selection,29 or of IGHV3 genes with very few HSMs.30 Very recently, analysis of 37 NMZL cases collected from public databases and collaborative multi-institutional studies confirmed the predominant involvement of the IGHV4-34 gene in this MZL subtype and the presence of HSMs with the majority of IGHV sequences.31 Of note, preferential involvement of the IGHV1-69 gene has also been found in HCV-associated NMZL,28 but as this gene is frequently found in other HCV-associated lymphoma types, this may merely reflect the viral infection context. Taken together, the data support a memory B-cell origin, or in cases where ongoing HSMs have been demonstrated, a germinal center B-cell origin.27 Accordingly, these lymphomas exhibit a low frequency of activation-induced cytidine deaminase–mediated somatic mutations in some oncogenes such as BCL-6, PAX5, PIM1, RHO-H,32 further indicating a transit through the germinal centers.32,33

Morphology and immunophenotype

NMZL has a heterogeneous morphology in terms of both architecture and cytology.34,35 Different patterns of lymph node infiltration have been reported including marginal zone-like/perifollicular, inverse follicular, perisinusoidal, follicular via colonization of reactive follicles, and diffuse.11 A combination of different patterns in a single case is common. Cytologically, NMZLs show varying proportions of small lymphocytes, marginal zone-like cells, centrocyte-like cells, and monocytoid B cells. Plasma cell differentiation is a well-described feature of NMZL in 20% to 40% of cases. Unlike SMZL and MALT lymphoma, the neoplastic population often contains a relatively high proportion (>20%) of large blastic B cells, and the mitotic index is frequently elevated. Criteria for large-cell transformation in NMZL are poorly defined, and cases with apparently increased numbers of large cells may be challenging to treat.

The antigen expression profile found on NMZL cells is similar to that of other MZLs. These B cells express CD19+, CD20+, and CD79a+ and are usually Bcl-2 positive. They are typically sIgM+D−/G+, cIg+−, and Pax5+. Cells are frequently negative for CD5, CD10, CD23, and cyclin D1 typically although knowledge of phenotypical variation such as CD5, IgD expression in some cases and Bcl6 expression in large cells is important to recognize NMZL.34,35 Plasmacytic differentiation is commonly associated with expression of CD38, CD138, and MUM1.16

Cytogenetic and molecular features

Recurrent clonal abnormalities found in other MZL types have been described and can support NMZL diagnosis by ruling out other small B-cell lymphomas. This includes trisomy 3, trisomy 18, trisomy 7, trisomy 12, and del6q.36 The most frequent abnormalities are gain of chromosome 3 (affecting FOXP1, NFKBIZ, and BCL6), occurring in 24% of cases, and 18q23 (affecting NFATC1) occurring in about 50% of cases.36 Deletion of 7q, which is frequent in SMZL, is not present in NMZL.37 Translocations typically detected in MALT lymphoma such as the t(11;18)(q21;q21) are not found in NMZL.

Inactivation of the A20 gene (located on 6q23) by either somatic mutation and/or deletion has been described in 3 of 9 published cases analyzed. This is a common genetic aberration across all MZL subtypes that may contribute to lymphomagenesis via induction of constitutive NF-κB.38

Given the potential difficulty of distinguishing between lymphoma types on the basis of histology due to the presence of a marginal zone pattern or monocytoid B cells, markers specific to NMZL will not only aid diagnosis but also offer insight into potential therapeutic pathways for NMZL. Gene expression profiling studies have identified a set of markers with differential expression in NMZL compared with follicular lymphoma.39,40 Novel markers proposed to differentiate between these 2 entities include notably the myeloid cell nuclear differentiation antigen (MNDA), CHIT1, TGFBi, TAC1, miR-221, and miR-223 for NMZL. In addition, markers such as BCL6, HGAL, LMO2 for distinguishing follicular lymphoma, or the MYD88 L265P somatic mutation preferentially associated with Waldenström macroglobulinemia,41,42 will allow elimination of other diagnoses; algorithms are currently under discussion for this differential diagnosis.43 Regarding this latter point, NMZL with monoclonal paraproteinemia IgM should probably be screened for the MYD88 mutation.

Clinical outcome and prognostic factors in NMZL

The clinical outcome of NMZL patients is similar to that of other nodal indolent lymphomas. To date, the disease has not proven curable with classical chemotherapy and is characterized by a continuous pattern of relapses. Relapse at extranodal sites is rare, occurring predominantly in nodes. However, with improvements in available therapies as new agents and combinations have been developed, survival has increased significantly over the past 2 decades, with 5-year overall survival (OS) reaching 70% to 90% (Table 110,11,13,14,16,18-20,44,46 ).

OS and progression in published studies including NMZL patients

| Study . | No. of patients . | 5-y OS rate, % . | Median OS, y . | Median progression, y . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Armitage et al (1998)15 | 25 | 57 | ND | ND |

| Nathwani et al (1999)44 | 20 | 56 | ND | ND |

| Berger et al (2000)11 | 37 | 55 | ND | ND |

| Camacho et al (2003)16 | 22 | 79 | ND | ND |

| Arcaini et al (2004)13 | 9 | ND | Not reached | 2.8 |

| Traverse-Glehen et al (2006)12 | 21 | 64 | ND | 1.3 |

| Oh et al (2006)18 | 36 | 83 | 5.5 | 1.3 |

| Arcaini et al (2007)14 | 47 | 69 | Not reached | 2.6 |

| Kojima et al (2007)45 | 65 | 85 | ND | ND |

| Orciuolo (2010)46 | 89 | 96 | ND | ND |

| Heilgeist et al (2012)20 | 32 | 89 | ND | ND |

| Olszewski & Castillo (SEER) (2013)10 | 4724 | 77* | ND | ND |

| Study . | No. of patients . | 5-y OS rate, % . | Median OS, y . | Median progression, y . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Armitage et al (1998)15 | 25 | 57 | ND | ND |

| Nathwani et al (1999)44 | 20 | 56 | ND | ND |

| Berger et al (2000)11 | 37 | 55 | ND | ND |

| Camacho et al (2003)16 | 22 | 79 | ND | ND |

| Arcaini et al (2004)13 | 9 | ND | Not reached | 2.8 |

| Traverse-Glehen et al (2006)12 | 21 | 64 | ND | 1.3 |

| Oh et al (2006)18 | 36 | 83 | 5.5 | 1.3 |

| Arcaini et al (2007)14 | 47 | 69 | Not reached | 2.6 |

| Kojima et al (2007)45 | 65 | 85 | ND | ND |

| Orciuolo (2010)46 | 89 | 96 | ND | ND |

| Heilgeist et al (2012)20 | 32 | 89 | ND | ND |

| Olszewski & Castillo (SEER) (2013)10 | 4724 | 77* | ND | ND |

ND, not done

Relative survival.

Conflicting data have been reported in terms of comparative survival outcomes for NMZL vs MALT and SMZL. In the prerituximab era, NMZL had a worse outcome compared with MALT lymphoma.11 It is unclear whether the introduction of rituximab has influenced the prognosis of NMZL patients relative to SMZL and MALT lymphoma, with 2 retrospective analyses and a large SEER database analysis of 15 908 MZL patients reporting conflicting data in terms of significant differences in progression-free survival (PFS) or OS.10,20,46 Nonetheless, overall, data suggest that NMZL is characterized by a worse outcome than MALT lymphoma, with the caveat of taking into consideration that MALT lymphoma patients present much more frequently with localized disease compared with NMZL and that a recent Nordic analysis reported that localized NMZL did not carry a worse prognosis than localized MALT lymphoma.47

Two existing prognostic indexes, the International Prognostic Index (IPI) and the Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (FLIPI) discriminate between lymphoma patients with high and low risk in terms of survival. The FLIPI has been reported to have some prognostic value in NMZL patients (Table 210,14,16,18-20,48 ).20 Various biological characteristics of tumor cells have been reported to be significantly associated with survival, including loss of survivin, active caspase 3, and overexpression of cyclin E.16 Lack of expression of MUM1/IRF4 and Ki67 in <5% of the cells has been associated with a better prognosis.40,48 Nonetheless, as these conclusions are mainly derived from retrospective studies with limited patient numbers and nonuniform treatment approaches, they should be interpreted with caution. Likewise, various clinical characteristics have been associated with survival prognosis, notably older age, advanced-stage disease, and the presence of B symptoms. Nonetheless, with the small patient numbers and the heterogeneity of treatment in these studies, it is not surprising that an NMZL-specific prognostic score has yet to be published.

Clinical and biological adverse prognostic factors in NMZL

| Factor . | PFS . | OS . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N= . | Reference . | N= . | Reference . | |

| Age >60 y | 36 | 18 | 47; 65; 4188* | 14; 19; 10 |

| Elevated LDH | 36 | 18 | 47 | 14 |

| Hb <12 g/dL | 36; 47 | 18; 14 | 36 | 18 |

| BM+ | 36 | 18 | 36; 47 | 18; 14 |

| ECOG ≥2 | 36 | 18 | 36 | 18 |

| Stage III/IV | 36 | 18 | 36; 4188* | 18; 10 |

| B symptoms | 47 | 14 | 36; 4188* | 18; 10 |

| No anthracycline | 36 | 18 | ||

| Survivin | 27 | 16 | ||

| Caspase 3 | 27 | 16 | ||

| FLIPI 3-5 | 32 | 20 | ||

| Male | 4188* | 10 | ||

| HCV+ | 47 | 14 | ||

| Cyclin E | 27 | 16 | ||

| Ki67 | 12 | 48 | ||

| IRF4 | 12 | 48 | ||

| FLIPI 3-5 | 32 | 20 | ||

| Factor . | PFS . | OS . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N= . | Reference . | N= . | Reference . | |

| Age >60 y | 36 | 18 | 47; 65; 4188* | 14; 19; 10 |

| Elevated LDH | 36 | 18 | 47 | 14 |

| Hb <12 g/dL | 36; 47 | 18; 14 | 36 | 18 |

| BM+ | 36 | 18 | 36; 47 | 18; 14 |

| ECOG ≥2 | 36 | 18 | 36 | 18 |

| Stage III/IV | 36 | 18 | 36; 4188* | 18; 10 |

| B symptoms | 47 | 14 | 36; 4188* | 18; 10 |

| No anthracycline | 36 | 18 | ||

| Survivin | 27 | 16 | ||

| Caspase 3 | 27 | 16 | ||

| FLIPI 3-5 | 32 | 20 | ||

| Male | 4188* | 10 | ||

| HCV+ | 47 | 14 | ||

| Cyclin E | 27 | 16 | ||

| Ki67 | 12 | 48 | ||

| IRF4 | 12 | 48 | ||

| FLIPI 3-5 | 32 | 20 | ||

BM, bone marrow; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; Hb, hemoglobin; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

Lymphoma-specific survival.

Current NMZL treatments

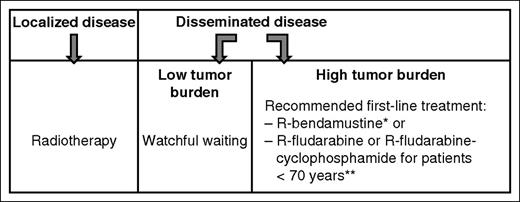

As of today, there are no standard recommended treatments for NMZL. Typically, the same strategy as that used for follicular lymphoma is initially proposed for NMZL patients (Figure 149,50 ).51 Patients with strictly localized disease may be considered for localized radiation therapy. In cases of low tumor burden, a watchful waiting strategy is usually employed, whereas in disseminated-stage disease, immunochemotherapy (rituximab plus chemotherapy with or without an anthracycline) is considered an appropriate option. In the context of NMZL, this raises the question as to possible choices in terms of classical chemotherapy and whether rituximab-bendamustine should be the new gold standard for first-line treatment. These treatment options are elaborated in the next paragraph.

Standard first-line treatment approaches in adult NMZL not associated with HCV. Treatment follows the approach used with follicular lymphoma. *R-bendamustine > R-CHOP: PFS, 69.5 vs 32.1 months (hazard ratio, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.44-0.74; P < .0001).49 **Fludarabine > chlorambucil; PFS, 36.3 vs 27.1 months, P = .01250 ; because of the toxicity profile, R-fludarabine or R-fludarabine-cyclophosphamide should only be proposed to patients <70 years of age. Note: There is no evidence for recommending maintenance with rituximab or an intensive treatment plus autologous stem cell transplantation in first line.

Standard first-line treatment approaches in adult NMZL not associated with HCV. Treatment follows the approach used with follicular lymphoma. *R-bendamustine > R-CHOP: PFS, 69.5 vs 32.1 months (hazard ratio, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.44-0.74; P < .0001).49 **Fludarabine > chlorambucil; PFS, 36.3 vs 27.1 months, P = .01250 ; because of the toxicity profile, R-fludarabine or R-fludarabine-cyclophosphamide should only be proposed to patients <70 years of age. Note: There is no evidence for recommending maintenance with rituximab or an intensive treatment plus autologous stem cell transplantation in first line.

Current combinations include rituximab/cyclophosphamide/vincristine/prednisone (R-CVP),52 rituximab/fludarabine (FR),53 and fludarabine/cyclophosphamide/rituximab (FCR),54 (although only a limited number of patients have been treated), with reported overall response rates (ORRs) >85% and 3-year PFS in the range of 60% to 90%. Of note, in the trial evaluating FR, excessive toxicity was reported and only 58% of these MZL patients completed the planned protocol.53 In a retrospective comparison of 47 NMZL patients treated with 2-CdA with or without rituximab, the ORR, complete response rate, and time to relapse were all superior with combination therapy.46

As the most common treatment of all lymphomas, anthracycline-containing chemotherapy (rituximab/cyclophosphamide/doxorubicin/vincristine/prednisone [R-CHOP]) is commonly used to treat NMZL patients; however, there are no convincing data justifying its recommendation in this patient population. Berger et al recommended anthracycline-containing chemotherapy in the presence of an increased number of large cells (>50% of the neoplastic cell population),11 however, the Italian LL01 randomized study, including 23 MZL patients, showed that the addition of epirubicin to chlorambucil did not improve the ORR, PFS, or OS compared with chlorambucil alone.55

Bendamustine-rituximab (BR) was tested as first-line therapy in a multicenter, randomized, phase 3 study comparing the efficacy and safety of BR vs R-CHOP in 549 indolent lymphomas (including 67 MZL, 41 lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma, 21 small lymphocytic lymphoma).49 In the overall study population, after a median follow-up of 45 months, median PFS was longer in the BR group than with R-CHOP (69.5 vs 31.2 months; hazard ratio, 0.58; 95% confidence interval, 0.44-0.74; P < .0001). BR was less frequently associated with serious adverse events than R-CHOP (19% vs 29%), notably severe infectious complications with fatal outcomes. The very small proportion of MZL patients included limits unequivocal extrapolation of this data to NMZL patients. Preliminary data from an ongoing phase 2 Italian study using first-line BR in a subset of indolent nonfollicular B-cell lymphoma patients have confirmed these results.54,56

Of note, HCV+ patients may benefit from antiviral therapy and do not need immediate cytoreductive treatment.24 Antiviral therapy results in HCV-RNA clearance and consequent tumor regression in most patients. It has also been shown that antiviral therapy used at any time is associated with improved OS.24

Interestingly, pediatric NMZL was described as a separate variant of NMZL in the most recent WHO classification of tumors of hematologic and lymphoid tissues in light of its distinct clinical presentation and given that it stands out as an indolent disease with remarkably better overall prognosis compared with classic NMZL.57 As such, a watchful waiting strategy may be a more appropriate approach than an aggressive strategy with chemotherapy.

Deregulated signaling pathways in NMZL as potential targets

As genetic research moves forward, large-scale molecular biology screening has permitted major steps forward in a short period of time. This approach has been successfully exploited in many disease areas to identify potential therapeutic targets, as is also the case for NMZL. Transcriptomic analyses of 15 NMZL cases was reported in 2012, proposing a specific “NMZL signature” composed of 264 upregulated and 184 downregulated genes.40 Deregulated pathways included B-cell receptor (BCR) signaling, interleukins (IL-2, IL-6, IL-10), integrin signaling (CD40), and cell survival pathways (MAPKs, tumor necrosis factor, transforming growth factor-β, and NF-κB), revealing survival pathways activated in NMZL. In addition, a tumor necrosis factor–family receptor for differentiation and NF-κB activation and CD74 (antigen presentation and B-cell maturation) may serve as potential therapeutic targets.

Data presented at the 2014 American Society of Hematology (ASH) annual meeting reported characterization of multiple deregulated pathways in NMZL by integrating studies combining whole-exome sequencing, deep sequencing of tumor-related genes, high-resolution small nucleotide polymorphism array, and RNAseq.58 Thirty-five cases were analyzed and 39 genes were shown to be recurrently affected by mutations (30 genes) or focal copy-number aberrations (9 genes) in 3 patients (9%). Among them, MLL2 (34% of cases), protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor δ (PTPRD) tumor suppressor (20%), and NOTCH2 (20%) were the most frequently mutated. The study identified several deregulated pathways whose combinations appear to be specific for NMZL across mature B-cell tumors, notably JAK/STAT (43% of cases), NF-κB (54%), NOTCH (40%), and Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling (17%), cell cycle (43%), chromatin remodeling/transcriptional regulation in terms of epigenetic modifiers, histones or transcriptional co-repressors (71%), and immune escape via T-cell–mediated tumor surveillance (14%-17%). These transcriptomic analyses offer fertile ground for the development of future therapeutic new targets. In the following section, we describe studies evaluating agents inhibiting these various candidate targets.

Treatment perspectives and novelties

The past 5 years have seen a revolution in the treatment of lymphoid malignancies, including NMZL. New knowledge in terms of its biological features along with the engineering of novel drugs has resulted in innovative options in the therapeutic strategy for this disease group, combining improved activity with increasingly acceptable toxicity profiles. This has opened the door to therapeutic options based on targeting signaling pathways and overcoming potential resistance due to mutational redundancies from multiple pathways. However, because of the rarity of NMZL, preclinical and clinical research specific to this entity is sporadic, with specific clinical trials few and far between. Those that have been performed include only a limited number of patients, making it extremely challenging to obtain a comprehensive view of the efficacy of new agents in MZL. In some cases, MZL entities are incorporated into larger trials designed for a biologically similar indolent disease, and in particular follicular lymphoma. Emerging results of trials evaluating new therapeutic opportunities are described in the next paragraph. A summary of completed studies in MZL patients including NMZL is presented in Table 359-66 and ongoing studies are summarized in Table 4.

Novel treatments in clinical trials including MZL patients with relapsed/refractory NHL or relapsed BCL

| Pathway . | Drug . | Target . | No. of evaluable MZL patients* . | Response . | Limiting toxicity . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name . | Reference . | |||||

| PI3K/AKT/mTOR | Everolimus | 59 | mTOR | 24 MZL (16 MALT; 4 NMZL) | CR 4%-ORR 28% | Hematologic (46% G3/4), interstitial pneumonia (4%) |

| Idelalisib | 60 | PI3K-d | 15 MZL | CR 6%-ORR 57% | Neutropenia (27% G3/4), aminotransferase elevations (13% G3/4), diarrhea (13% G3/4), pneumonia (7% G3/4) | |

| Copanlisib | 61 | PI3K-d and PI3K-α | 3 MZL | ORR 2/3 | Hypertension (49% G3/4), neutropenia (30% G3/4), hyperglycemia (30% G3/4), anemia (15% G3/4) | |

| BCR | Ibrutinib | 62 | BTK | 4 MZL | ORR 1/4 | Diarrhea (< 5% G3/4), neutropenia (13% G3/4), thrombocytopenia (7% G3/4), anemia (7% G3/4) |

| Apoptosis | ABT-199 | 63 | BCL2 | 3 MZL | Unknown for MZL | Neutropenia (27%), anemia (19%), thrombocytopenia (19%), febrile neutropenia (12%) |

| Microenvironment | Lenalidomide | 64 | Immunomodulator | 40 MZL | CR 65% ORR 86% | Neutropenia (35%), muscle pain (9%), rash (7%), cough, dyspnea, or other pulmonary symptoms (5%), thrombosis (5%), thrombocytopenia (4%) |

| Proteasome | Bortezomib | 65,66 | Proteasome | 48 MALT | CR 35% ORR 64% | Peripheral neuropathy (65%) |

| Pathway . | Drug . | Target . | No. of evaluable MZL patients* . | Response . | Limiting toxicity . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name . | Reference . | |||||

| PI3K/AKT/mTOR | Everolimus | 59 | mTOR | 24 MZL (16 MALT; 4 NMZL) | CR 4%-ORR 28% | Hematologic (46% G3/4), interstitial pneumonia (4%) |

| Idelalisib | 60 | PI3K-d | 15 MZL | CR 6%-ORR 57% | Neutropenia (27% G3/4), aminotransferase elevations (13% G3/4), diarrhea (13% G3/4), pneumonia (7% G3/4) | |

| Copanlisib | 61 | PI3K-d and PI3K-α | 3 MZL | ORR 2/3 | Hypertension (49% G3/4), neutropenia (30% G3/4), hyperglycemia (30% G3/4), anemia (15% G3/4) | |

| BCR | Ibrutinib | 62 | BTK | 4 MZL | ORR 1/4 | Diarrhea (< 5% G3/4), neutropenia (13% G3/4), thrombocytopenia (7% G3/4), anemia (7% G3/4) |

| Apoptosis | ABT-199 | 63 | BCL2 | 3 MZL | Unknown for MZL | Neutropenia (27%), anemia (19%), thrombocytopenia (19%), febrile neutropenia (12%) |

| Microenvironment | Lenalidomide | 64 | Immunomodulator | 40 MZL | CR 65% ORR 86% | Neutropenia (35%), muscle pain (9%), rash (7%), cough, dyspnea, or other pulmonary symptoms (5%), thrombosis (5%), thrombocytopenia (4%) |

| Proteasome | Bortezomib | 65,66 | Proteasome | 48 MALT | CR 35% ORR 64% | Peripheral neuropathy (65%) |

BCL, B-cell lymphoma; CR, complete remission; G, grade; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

The number of patients with MALT, SMZL, and NMZL was not systematically available.

Ongoing trials for MZL including NMZL patients

| Compound . | Clinical setting . | Class . | Target . | Ongoing trial . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase . | No. of patients . | Comparator . | Primary end point . | Trial status . | ||||

| Obinutuzumab | Rituximab-refractory MZL (among iNHL) | mAb | CD20 | III (combo with bendamustine) | 414 | Bendamustine | PFS | Complete |

| Relapsed MZL (among iNHL) | I/II (combo with lenalidomide) | 72 | MTD, DLT | Recruiting (est. compl. 5/2016) | ||||

| Ibrutinib | r/r MZL (among iNHL) | iTK | BTK, ITK | III (combo with BR or rituximab only) | 400 | R-CHOP | PFS | Active (est. compl. 8/2012) |

| r/r MZL | II | 60 | ORR | Active, not recruiting (est. 12/2017) | ||||

| Relapsed MZL (among B-cell NHL) | I (combo with lenalidomide) | 34 | DLT, MTD, safety | 12/2015 (primary outcome measure) | ||||

| Lenalidomide | r/r MZL (among iNHL) | Small-molecule IMiDs | Immuno-modulatory | I (combo with rituximab and bendamustine) | 26 | MTD | Active, nonrecruiting (est. compl. 11/2016) | |

| r/r MZL (among B-cell NHL) | I/II (combo with romidepsin and rituximab) | 56 | MTD, ORR | Not yet recruiting (est. compl. 10/2020) | ||||

| r/r MZL (together with follicular lymphoma) | III (combo with rituximab) | 350 | Rituximab + placebo | PFS | 12/2016 | |||

| Ublituximab | r/r MZL (among B-cell NHL) | mAb | CD20 | I/II | 60 | MTD, safety | Complete | |

| Idelalisib | Rituximab and alkylating agents-refractory MZL (among iNHL) | Small molecule | PI3K | II | 125 (15 MZL) | ORR | Active, nonrecruiting (est. compl. 12/2015) | |

| r/r MZL (among iNHL) | III (combo with rituximab) | 375 | Rituximab + placebo | PFS | Recruiting (est. compl. 6/2022) | |||

| Idelalisib + GS-9973 | r/r hematologic malignancies | Small molecules | PI3K | II | 66 | ORR | Active, nonrecruiting (est. compl. 9/2015) | |

| Syk | ||||||||

| Duvelisib | Rituximab and CT or RIT-refractory MZL (among iNHL) | Small molecule | PI3K | II | 120 | ORR | Recruiting (est. compl. 1/2018) | |

| Compound . | Clinical setting . | Class . | Target . | Ongoing trial . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase . | No. of patients . | Comparator . | Primary end point . | Trial status . | ||||

| Obinutuzumab | Rituximab-refractory MZL (among iNHL) | mAb | CD20 | III (combo with bendamustine) | 414 | Bendamustine | PFS | Complete |

| Relapsed MZL (among iNHL) | I/II (combo with lenalidomide) | 72 | MTD, DLT | Recruiting (est. compl. 5/2016) | ||||

| Ibrutinib | r/r MZL (among iNHL) | iTK | BTK, ITK | III (combo with BR or rituximab only) | 400 | R-CHOP | PFS | Active (est. compl. 8/2012) |

| r/r MZL | II | 60 | ORR | Active, not recruiting (est. 12/2017) | ||||

| Relapsed MZL (among B-cell NHL) | I (combo with lenalidomide) | 34 | DLT, MTD, safety | 12/2015 (primary outcome measure) | ||||

| Lenalidomide | r/r MZL (among iNHL) | Small-molecule IMiDs | Immuno-modulatory | I (combo with rituximab and bendamustine) | 26 | MTD | Active, nonrecruiting (est. compl. 11/2016) | |

| r/r MZL (among B-cell NHL) | I/II (combo with romidepsin and rituximab) | 56 | MTD, ORR | Not yet recruiting (est. compl. 10/2020) | ||||

| r/r MZL (together with follicular lymphoma) | III (combo with rituximab) | 350 | Rituximab + placebo | PFS | 12/2016 | |||

| Ublituximab | r/r MZL (among B-cell NHL) | mAb | CD20 | I/II | 60 | MTD, safety | Complete | |

| Idelalisib | Rituximab and alkylating agents-refractory MZL (among iNHL) | Small molecule | PI3K | II | 125 (15 MZL) | ORR | Active, nonrecruiting (est. compl. 12/2015) | |

| r/r MZL (among iNHL) | III (combo with rituximab) | 375 | Rituximab + placebo | PFS | Recruiting (est. compl. 6/2022) | |||

| Idelalisib + GS-9973 | r/r hematologic malignancies | Small molecules | PI3K | II | 66 | ORR | Active, nonrecruiting (est. compl. 9/2015) | |

| Syk | ||||||||

| Duvelisib | Rituximab and CT or RIT-refractory MZL (among iNHL) | Small molecule | PI3K | II | 120 | ORR | Recruiting (est. compl. 1/2018) | |

BR, bendamustine/rituximab; combo, combination; CT, chemotherapy; DLT, dose-limiting toxicity; est. compl., estimated completion; iNHL, indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma; iTK, tyrosine-kinase inhibitor; ITK, inhibitor of tyrosine kinase; mAb, monoclonal antibody; MTD, maximum tolerated dose; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; r/r = relapsed/refractory; RIT, radioimmunotherapy.

The NF-κB pathway is unequivocally deregulated in MZL, and specifically in NMZL.58,67 The proteasome inhibitor, bortezomib, targeting the NF-κB pathway, has demonstrated promising activity in both NMZL and MALT lymphoma, achieving complete or partial remissions in patients failing previous therapies.65,66,68 In the trial reported by Conconi et al, 31 patients with relapsed/refractory MALT lymphoma received 1.3 mg/m2 bortezomib on days 1, 4, 8, and 11 for up to six 21-day cycles.65 Among the 29 patients assessable for response, the ORR was 48%, including 9 patients who achieved a complete response. Similar activity was seen when bortezomib was combined with rituximab, with 2 combination regimens proving effective in relapsed/refractory MZL, as documented in a randomized trial in which 81 patients received 375 mg/m2 rituximab weekly for 4 weeks with either 1.3 mg/m2 bortezomib twice weekly or 1.6 mg/m2 bortezomib weekly.69 The ORR was 49% with twice-weekly bortezomib and 43% with the weekly regimen (including 10% complete response). Disappointingly, the high rate of neuropathy (up to 65% of patients) dramatically limits the clinical usefulness of proposing this agent to patients.

Critical evidence has been accumulating for the centrality of the BCR signaling pathway in the majority of B-cell malignancies, including NMZL. Small-molecule inhibitors of kinases involved in B-cell signaling represent a booming area of research, including phosphoinositide 3-kinase and Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK). Several inhibitors of the phosphoinositol 3 kinase (PI3K)/AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway have been tested in MZL patients including everolimus,59 idelalisib,60 and copanlisib,61 with responses observed in the relapse setting. Ibrutinib, targeting BCR signaling via BTK, is currently under investigation in the relapse MZL setting (PCYC1121, clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT01980628). Data from this, the only trial performed to date, should be available in 2016, and discussions over combining rituximab with ibrutinib have already been initiated.

NOTCH orchestrates an important cell-fate switch in the hematopoietic system, with this binary switch now well characterized in terms of the T-cell over B-cell switch, marginal zone B cell over follicular B cell, and erythroid cell over myeloid cell choices.70 The NOTCH family comprises 4 transmembrane receptors (NOTCH1-4). These receptors engage 1 of 5 ligands, Jagged (Jag) 1, 2 or Δ-like (DLL) 1, 3, 4, and are ultimately cleaved by γ-secretase, liberating the signaling-competent, intracellular domain from the membrane (NOTCHIC). NOTCHIC then interacts with proteins in the cytoplasm, such as NF-κB, or translocates to the nucleus to mediate downstream gene transcription, including the classical targets Hairy enhancer of split (Hes), and Hes-related with YRPW motif.71 NOTCH signaling has been suggested to be of major importance in MZL, including NMZL and SMZL, given that NOTCH1 and 2 are among the most commonly mutated genes in these diseases.58 The development of a novel agonist specifically targeting the NOTCH2 receptor may represent a promising strategy for NMZL.72

The JAK/STAT pathway also appears to contribute to cell survival signaling in NMZL in a specific manner compared with the other MZL entities, as demonstrated by the exome-sequencing analysis58 with mutations in numerous kinases in this pathway. Specific inhibitors such as ruxolitinib (INCB018424) a small-molecule adenosine triphosphate mimetic, inhibits both JAK1 and JAK2. It is already used to treat myelofibrosis, a bone marrow disorder, and is being investigated for the treatment of certain cancers and autoimmune diseases.73

TLR signaling is a key deregulated signaling pathway in NMZL. MYD88 is an important linker protein in signaling via TLRs 7, 8, 9, and IL-1R.58 After ligand stimulation, TLR/IL-1R interacts with MYD88 via the Toll/IL-1R domain. MYD88 binds subsequently via its death domain IRAK1 which in turn phosphorylates and activates IRAK4. In association with TRAF6 and TAK1, the IRAK1/IRAK4/MYD88 complex activates the NF-κB pathway. Strategies targeting TLR, IRAK4, and TAK1 mediator proteins of MYD88 signaling or MYD88 homodimerization are in clinical and preclinical development, but research to date is essentially in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

BCL2 is overexpressed in NMZL making targeting apoptosis via BCL2 inhibitors such as ABT-199 another potential option.74 However, as yet, no clinical data are available. Immunomodulatory drugs are oral immunomodulators with direct antineoplastic activity and immunologic effects, including blocking tumor cell proliferation and angiogenesis, and stimulating T-cell and natural killer cell–mediated cytotoxicity in experimental models.75,76 Antineoplastic and antiproliferative effects as well as increased natural killer cell numbers and activity have been observed in vitro and in vivo against malignant lymphoma B cells in general77 and specifically against diffuse large B-cell, follicular, and mantle cell lymphoma cells.78,79 The first-generation immunomodulatory drug, thalidomide, showed a lack of efficacy when administered as monotherapy in a small pilot study,80 however, the second-generation molecule lenalidomide, administered either alone at 25 mg per day or combined with rituximab in MALT lymphoma, showed a 70% ORR in a phase 2 trial as monotherapy and an impressive 86% when combined with rituximab.64,81

Importantly, these biological insights and knowledge of the toxicity profiles of the novel available drugs provide guidance to physicians when deciding whether or not to combine these agents with classical chemotherapy. In addition, there is no doubt that, as in all cancers, the microenvironment is of major importance and targeting it with anti-PD1 or anti-PDL1/2 may be an important next step.

Conclusion

NMZL is considered a distinct entity among non-Hodgkin lymphomas, and more particularly among the indolent small B-cell lymphomas, with unique clinical and morphological characteristics. Although characterized by a very different clinical presentation compared with SMZL and MALT lymphoma, striking similarities in their epidemiology and tumor cell biology support a common origin in the B cells of the marginal zone, making outcomes of clinical trials in these 2 other MZL entities of interest for NMZL.

Until now, immunochemotherapy has formed the backbone of NMZL treatment, but this situation is rapidly evolving. Personalized medicine for NMZL patients will integrate clinicopathologic features of the disease combined with state-of-the-art molecular profiling to create diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic strategies tailored to specific patient and disease requirements. This will improve therapeutic efficacy with targeted treatments, although for now, few data have been generated to allow novel strategies to be defined. In the past 5 years, an extensive collaborative effort by biologists, pathologists, and clinicians has resulted in agreement on more stringent criteria for disease diagnosis and for evaluation of clinical response. These efforts support the design of further prospective clinical trials to define the optimal targeted therapeutic approach to NMZL.

Authorship

Contribution: C.T., T.M., and F.D. wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Catherine Thieblemont, Hemato-oncologie, Hôpital Saint-Louis, AP-HP, 1, Ave Claude Vellefaux, 75010, Paris, France; e-mail: catherine.thieblemont@aphp.fr.