In this issue of Blood, Simon and colleagues provide the first proof that dengue virus (DENV) raids platelets and steals their translational machinery to replicate and produce infectious virus.1

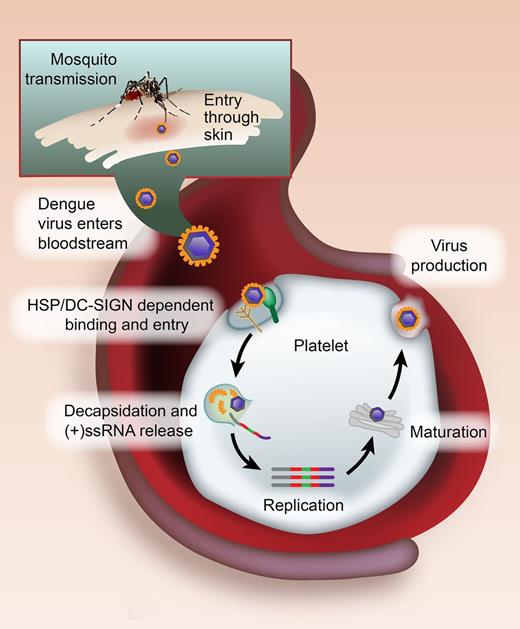

Model of DENV binding and replication by platelets. DENV belongs to the Flaviviridae family and is transmitted to humans by infected female mosquitoes of the Aedes genus. When an infected mosquito bites a human, DENV enters the bloodstream and binds to platelets via heparin sulfate proteoglycans (HSP) and DC-SIGN. Through mechanisms that are unresolved, the DENV enters into platelets and the viral particle is uncoated (decapsidation). This uncoating process releases the (+)ssRNA virus genome into the cytosol, where the (+)ssRNA directs the synthesis of viral proteins, and then the generation of a minus strand, which is transcribed into new plus-stranded molecules (replication). Nucleocapsid assembly and maturation ensue in the Golgi, leading to infectious virus production. See Figure 7 in the article by Simon et al that begins on page 378.

Model of DENV binding and replication by platelets. DENV belongs to the Flaviviridae family and is transmitted to humans by infected female mosquitoes of the Aedes genus. When an infected mosquito bites a human, DENV enters the bloodstream and binds to platelets via heparin sulfate proteoglycans (HSP) and DC-SIGN. Through mechanisms that are unresolved, the DENV enters into platelets and the viral particle is uncoated (decapsidation). This uncoating process releases the (+)ssRNA virus genome into the cytosol, where the (+)ssRNA directs the synthesis of viral proteins, and then the generation of a minus strand, which is transcribed into new plus-stranded molecules (replication). Nucleocapsid assembly and maturation ensue in the Golgi, leading to infectious virus production. See Figure 7 in the article by Simon et al that begins on page 378.

Dengue is a viral disease spread by mosquitoes that is primarily observed in subtropical and tropical regions but with increased globalization has begun invading all corners of the world. Upon infection, DENV induces a spectrum of clinical manifestations that range from a self-limiting fever to a more severe form (dengue hemorrhagic fever) that can progress to increased vascular permeability, shock, and death. Dengue infection commonly results in thrombocytopenia (in both mild and severe forms), and platelets have emerged as key voyagers in the pathogenesis of dengue.

Recent studies have shown that dengue induces platelet activation and apoptosis, which modulate inflammatory responses in target monocytes.2,3 Additionally, dengue infection triggers the synthesis and release of interleukin-1β (IL-1β) by human platelets.4 Although binding of dengue to the dendritic cell–specific intracellular adhesion molecule-3–grabbing nonintegrin (DC-SIGN) has been implicated in platelet activation, apoptosis, and IL-1β synthesis, the authors substantiate that dengue directly binds DC-SIGN on the surface of platelets. Binding of dengue to DC-SIGN, however, also requires heparin sulfate proteoglycan and is significantly enhanced by thrombin. The DENV readily binds platelets at 37°C, but binding is also observed at room temperature (25°C). Interestingly, the authors found that trypsinization did not remove all of the surface-bound DENV. This finding suggested that DENV may be internalized, initiating a search for replication of the virus in platelets.

Although there was no prior evidence that platelets replicate DENV, the virus has been detected in platelets isolated from dengue patients.5 Based on these findings and previous studies demonstrating that anucleate platelets are capable of translating their own messenger RNA,6 the authors postulated that the DENV could replicate its viral RNA by usurping the translational machinery of platelets. DENV is a positive-sense (+) single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) with a genome of ∼11 kb.7 The dengue genome encodes a polyprotein precursor that is cleaved to 3 structural proteins (a core protein, membrane-associated protein, and envelope protein) and 7 nonstructural (NS) proteins. The authors show that platelets synthesize NS1 protein and replicate the dengue viral genome. Intact platelets, but not damaged platelets (ie, freeze-thawed), were capable of replicating all 4 serotypes of dengue and as predicted, the authors’ studies revealed that platelets facilitate the generation of infectious DENV progeny. Production of infectious virus also indicates that platelets use functional Golgi components for nucleocapsid assembly and formation of virions.

This story has several implications. First and foremost, it provides compelling evidence that dengue replication occurs in platelets (see figure) and raises the possibility that other (+)ssRNA viruses may be similarly propagated by these anucleate cytoplasts. Although platelets are in a prime position to defend against blood-borne viruses, it appears that dengue takes advantage of this frontline positioning to board platelets and swipe their translational cargo as a mode of survival. Second, de novo synthesis of NS1 may have implications beyond its primary role in dengue replication. NS1 is reported to be released into the plasma, where it is highly immunogenic,8 and antiplatelet autoantibodies elicited by DENV NS1 induce thrombocytopenia in mice.9 Thus, it is conceivable that production of viral antigens may impact platelet clearance by immune complex formation. Finally, the findings by Simon et al provide important new insights relevant to human DENV infection and platelet transfusion practices. Previously, DENV-induced synthesis and release of IL-1β in platelet-derived microparticles have been linked to injurious systemic inflammatory response syndromes and increased vascular permeability.4 As DENV is now shown to commandeer human platelets, DENV may also use platelets to ship newly formed virions throughout the circulation and thus extend its infectious reach. Whether the thrombocytopenia that commonly occurs during dengue infection is a host-defense mechanism to limit viral dissemination remains to be determined. In addition, in the current report, DENV binding and replication in platelets occurred at 25°C, the temperature at which platelet concentrates are commonly stored prior to transfusion into recipient patients. As DENV infection may not always result in clinical symptoms, platelet concentrates collected from asymptomatic DENV-infected donors may serve as a reservoir for DENV transmission during platelet transfusions, especially in tropical or subtropical climates where DENV is endemic.

As pirates say, “batten down the hatches.” The elegant studies by Simon and cohorts suggest new and potentially hostile roles for human platelets when they are boarded and seized by DENV. “Shiver me timbers….”

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.