In this issue of Blood, Hofbauer et al1 provide an explanation to the puzzling observation that, in the plasma of healthy subjects and hemophilia A patients treated with factor VIII (FVIII) concentrates, the presence of anti-FVIII antibodies is not consistently associated with a reduction in FVIII activity. On the basis of these findings, they describe a novel sensitive method for the identification of the clinically relevant high-affinity anti-FVIII antibodies.1

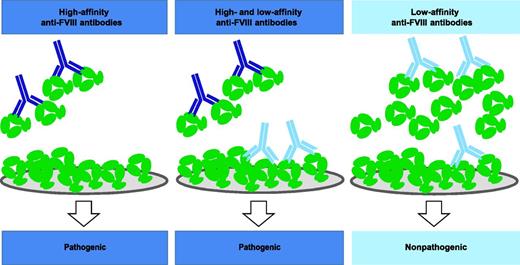

Competition-based ELISA discriminates between pathogenic high-affinity and nonpathogenic low-affinity anti-FVIII antibodies. High-affinity pathogenic antibodies (dark blue) interact with a low concentration of FVIII (green) in the fluid phase and therefore do not bind to FVIII insolubilized on a solid surface. On the contrary, low-affinity nonpathogenic antibodies (light blue) do not make complexes with a low concentration of FVIII in solution but bind to insolubilized FVIII, possibly because each antibody can interact with 2 FVIII molecules that are held in close proximity at the solid surface. High- and low-affinity antibodies bind to FVIII when it is present at a high concentration in solution. Only a fraction of low-affinity antibodies are then still available to interact with insolubilized FVIII. High-affinity antibodies are found only in hemophilia A patients treated with FVIII concentrates who develop FVIII inhibitors or in patients with acquired hemophilia A. The low-affinity anti-FVIII antibodies are found in hemophilia A patients with a normal response to FVIII concentrates and in healthy controls.

Competition-based ELISA discriminates between pathogenic high-affinity and nonpathogenic low-affinity anti-FVIII antibodies. High-affinity pathogenic antibodies (dark blue) interact with a low concentration of FVIII (green) in the fluid phase and therefore do not bind to FVIII insolubilized on a solid surface. On the contrary, low-affinity nonpathogenic antibodies (light blue) do not make complexes with a low concentration of FVIII in solution but bind to insolubilized FVIII, possibly because each antibody can interact with 2 FVIII molecules that are held in close proximity at the solid surface. High- and low-affinity antibodies bind to FVIII when it is present at a high concentration in solution. Only a fraction of low-affinity antibodies are then still available to interact with insolubilized FVIII. High-affinity antibodies are found only in hemophilia A patients treated with FVIII concentrates who develop FVIII inhibitors or in patients with acquired hemophilia A. The low-affinity anti-FVIII antibodies are found in hemophilia A patients with a normal response to FVIII concentrates and in healthy controls.

Hemophilia A is a hereditary bleeding disorder characterized by deficient or dysfunctional FVIII. Treatment includes the transfusion of plasma-derived or recombinant FVIII concentrates, which can result in the induction of anti-FVIII antibody production in up to 30% of patients with severe hemophilia.2 Anti-FVIII antibodies are also responsible for the autoimmune disorder acquired hemophilia A.

Anti-FVIII antibodies are currently detected in vitro by their capacity to inhibit FVIII activity in functional assays.3 However, these assays cannot detect antibodies that are directed toward the nonfunctional sites of FVIII, even though they may accelerate the clearance rate of FVIII4-6 and are therefore of pathological relevance. Alternative techniques such as the use of immunoblotting, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and immunoprecipitation have therefore been developed to detect a broader range of anti-FVIII antibodies. Recently, very sensitive techniques based on immunofluorescence have also been implemented.6,7 Such assays can also identify the isotypes and the immunoglobulin(Ig)G subclasses of the antibodies,7 notably, the IgG4 subclass, which predominates in the immune response to FVIII.8 Despite these advances, the usefulness of nonfunctional assays has remained questionable because they do not establish a clear distinction between pathogenic and nonpathogenic anti-FVIII antibodies. Nonpathogenic antibodies can be found in healthy donors and in some hemophilia A patients treated with FVIII concentrates and do not elicit the clinical manifestations associated with inhibitor development.

To better discriminate between the different types of anti-FVIII antibodies, Hofbauer et al1 have taken into account antibody affinities. Such studies have previously been attempted with monoclonal antibodies. For example, the affinity of the human monoclonal antibody BO2C11, which was produced by the immortalization of B lymphocytes from a patient with a high titer inhibitor, was determined by Scatchard analysis of FVIII inhibition and surface plasmon resonance.9 The high affinity of this antibody (KA ≥ 1011 M) correlated with the congruence observed in crystallography between the antibody binding site and the phospholipid binding site of the FVIII C2 domain.10 Unfortunately, these techniques for evaluating the affinity of monoclonal antibodies cannot be used for polyclonal antibodies such as anti-FVIII antibodies in the plasma of patients.

Hofbauer et al1 have therefore developed a sensitive ELISA platform that can discriminate between high- and low-affinity anti-FVIII antibodies in plasma. In this assay, both types of antibodies are able to bind to FVIII insolubilized on ELISA plates, possibly because in these circumstances, the antibodies can bind to 2 FVIII molecules that are held in close proximity at the solid surface (see figure). However, the activity of low- vs high-affinity antibodies differs when FVIII is added in the fluid phase. According to the law of mass action, only high-affinity antibodies make complexes with FVIII when FVIII is at a low concentration in solution. This prevents the high-affinity antibodies from being available to interact with insolubilized FVIII (see figure). In contrast, a high concentration of FVIII in solution allows low-affinity antibodies to make complexes with FVIII and reduces the binding of low-affinity antibodies to insolubilized FVIII (see figure).

Using this principle, Hofbauer et al1 have characterized anti-FVIII antibodies from different cohorts of patients with congenital and acquired hemophilia A and compared them to healthy individuals. They analyzed the apparent affinities of FVIII-specific antibodies found in patients with FVIII inhibitors detected through the Nijmegen-Bethesda assay.3 This revealed that antibody affinities from these patients were up to 100-fold higher than the affinities of antibodies found in hemophilia A patients without inhibitors and in healthy individuals. This novel method also appears to be much more sensitive for the detection of inhibitor than functional assays, because high-affinity anti-FVIII antibodies were detected in the plasma of one patient more than a year before the first detection of FVIII inhibitors.

These results suggest that the appearance of high-affinity antibodies against FVIII is a suitable marker for the early detection of a clinically relevant immune response to FVIII. This competition-based ELISA may therefore be of interest for evaluating the immunogenicity of novel FVIII concentrates in a well-standardized and sensitive manner. It may also help in identifying the poorly characterized noninhibitory antibodies suspected of accelerating the clearance of FVIII. Given that FVIII is at a low concentration in plasma (0.1-0.2 nM), such antibodies should have a high affinity for making complexes with FVIII.

The ability of this novel assay to detect early anti-FVIII antibody development may also have useful clinical applications for optimizing inhibitor eradication because the success rate of immune tolerance induction is higher when treatment is started early after inhibitor detection and when inhibitor titer is low. Similarly, this novel assay may be useful for the follow-up of patients with mild/moderate hemophilia A, in whom the spreading of an immune response from the allogeneic FVIII to the patient’s self FVIII can transform the patients’ bleeding phenotype into that of severe hemophilia A. In such patients, the detection of an initial immune response to allogeneic FVIII may allow their therapy to be adapted to prevent the development of an autoimmune response to self FVIII.

Prospective clinical studies will thus be needed to investigate the opportunities provided by this novel approach of inhibitor detection.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal