In this issue of Blood, Lu et al demonstrate the requirement of membrane localization for proper functioning of the human germinal center–associated lymphoma (HGAL) gene product in enhancing signals generated by engagement of the antigen receptor on germinal center B cells.1

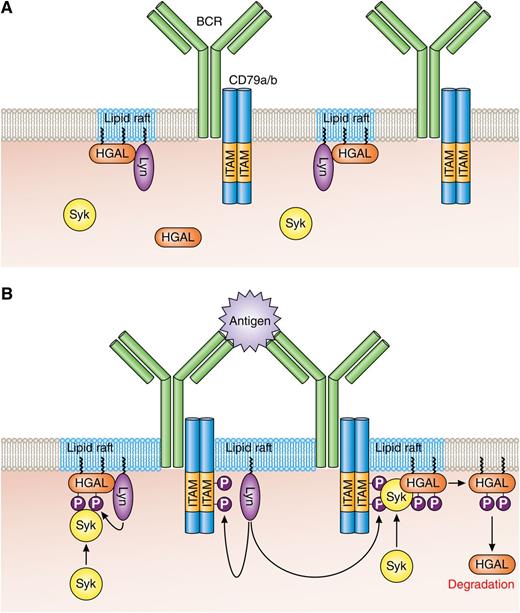

HGAL within lipid rafts enhances BCR signaling. (A) In resting B cells, HGAL is mainly located within lipid rafts together with Lyn. (B) In BCR-stimulated B cells, Lyn phosphorylates tyrosine residues within the ITAMs of CD79a/b, and this attracts and activates Syk. Coassociation of Syk with HGAL enhances Syk kinase activity and BCR signaling strength. Following BCR engagement, HGAL is shunted from lipid rafts to ultimately end up in the cell cytoplasm for destruction by the proteasome. Professional illustration by Patrick Lane, ScEYEnce Studios.

HGAL within lipid rafts enhances BCR signaling. (A) In resting B cells, HGAL is mainly located within lipid rafts together with Lyn. (B) In BCR-stimulated B cells, Lyn phosphorylates tyrosine residues within the ITAMs of CD79a/b, and this attracts and activates Syk. Coassociation of Syk with HGAL enhances Syk kinase activity and BCR signaling strength. Following BCR engagement, HGAL is shunted from lipid rafts to ultimately end up in the cell cytoplasm for destruction by the proteasome. Professional illustration by Patrick Lane, ScEYEnce Studios.

HGAL, also known as germinal center–expressed transcript 2, was first identified in profiling studies as an interleukin (IL)-4–inducible gene whose expression in cases of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) predicts for longer overall survival.2,3 As the name suggests, the protein product of HGAL is expressed in normal B cells undergoing the germinal center (GC) reaction and is typically observed in B-cell malignancies that originate within GCs such as follicular lymphomas, Burkitt’s lymphomas, and DLBCLs. A mouse homolog of HGAL, known as M17, is identified, but targeted disruption of its expression has only revealed that the presence of this protein is dispensable for the GC reaction.4 However, recent work by the Lossos laboratory,5 including the paper in this issue,1 has brought clarity to the role of HGAL in GC B cells and has also revealed directions for further research.

HGAL is already demonstrated by this group as an enhancer of antigen receptor (B-cell receptor [BCR]) signaling in GC B cells,5 and the paper by Lu et al is a biochemical study showing that this signal enhancing function of HGAL is crucially dependent on myristoylation, palmitoylation, and lipid raft localization. Thus, in resting B cells, a proportion of HGAL resides in lipid rafts together with the src family kinase Lyn (see panel A). Syk may associate with HGAL in these rafts, but such an association is likely nonproductive in terms of Syk kinase activity. BCR is, for the most part, also largely located outside these rafts. This all changes during BCR engagement (see panel B); BCR is recruited to lipid rafts where immunotyrosine activation motifs (ITAMs) within CD79a and b become phosphorylated by Lyn. This, in turn, attracts and activates Syk, which, through coassociation with HGAL (possibly by interacting with phospho-tyrosines within HGAL), has heightened kinase activity leading to enhanced induction of the BCR signaling pathway. Active Syk then catalyzes a phosphorylation reaction that rapidly sends HGAL out of the lipid raft/BCR signalosome and to the proteasome for destruction. Importantly, expressed cytosolic HGAL (ie, a mutant that can neither be myristoylated nor palmitoylated) does not associate with Syk, nor does it enhance BCR signaling. However, this does not mean cytosolic HGAL is without function. Ectopic expression of this HGAL mutant blocks cell migration in response to IL-6 and stromal cell–derived factor 1 (SDF-1), presumably through its described role in activating RhoA signaling and influencing actin/myosin dynamics.6,7

We can now dissect the function of HGAL and divide its role in mediating enhancement of BCR signaling from that in regulating cell migration. This ability potentially gives insight into why expression of HGAL is associated with good outcome in DLBCLs. BCR plays an important role in the pathogenesis of GC-derived lymphomas, and the signal enhancing effect of HGAL may provide growth signals to the malignant cells. Why HGAL expression is linked to good outcome in DLBCL is likely because of the role it plays in retaining malignant cells within the GC environment by keeping their migration in check.6,7 This notion is supported by demonstration that transgenic expression of HGAL in B cells leads to enlargement of Peyer’s patches,5 an organ where B lymphocytes require functional CXCR4 for egress.8 Considering that ectopic expression of HGAL inhibits cell migration to SDF-1 (CXCL12, the ligand of CXCR4), it is highly probable that the enlarged Peyer’s patches in HDAC-transgenic mice are due to restricted egress of B cells. Moreover, earlier findings from this group showing that miR-155 targets HGAL expression suggest that high expression of this micro-RNA in some cases of DLBCL may contribute to malignant cell dissemination and aggressive tumor behavior.9

A chief question now is whether HGAL works in concert with BCR signaling to block malignant cell migration. Critically, cytosolic HGAL is more efficient than wild-type HGAL in blocking cell migration. Conceivably, in BCR-stimulated cells, the efficiency with which wild-type HGAL is sent to the cytosol to inhibit migration will be key for holding these cells within the GC. However, wild-type HGAL is observed in the cytosol of resting DLBCL B-cell lines and can be induced by IL-4 in naïve B cells. In this case, the HGAL within cytoplasm may slow migration of B cells through T cell-rich regions of the white pulp to allow easier identification of cognate antigen for BCR stimulation. Overexpression of HGAL in this environment may stop B cells from migrating, and proliferative stimulation by IL-4 and T cell-expressed CD154 could then lead to development of the B-lymphoid hyperplasia and amyloidosis observed in splenic tissues of HGAL transgenic mice.5 What is now needed to more fully understand the functional interplay between HGAL’s role in enhancing BCR signaling and that in controlling B-cell migration is the generation of transgenic mice expressing cytosolic HGAL, and an exploration of how BCR cross-linking affects the migration of B cells that are HGAL positive and negative.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal