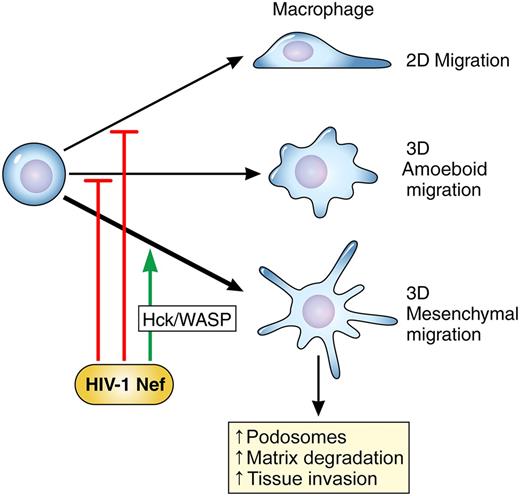

In this issue of Blood, Vérollet et al show that expression of the HIV-1–derived protein Nef alters the migratory mode adopted by macrophages, enhancing macrophage tissue infiltration and explaining the observed accumulation of tissue-resident macrophages in some HIV-infected patients.1

HIV-1 infection of macrophages, through the expression of the HIV-1–derived protein Nef, pushes macrophages to adopt the “mesenchymal” mode of migration through effects upon the src-family kinase Hck and a downstream effector, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein (WASP). Migratory macrophages that employ the mesenchymal mode are better able to invade dense extracellular matrix and tissues. Results from Vérollet et al provide a mechanistic understanding of the increased infiltration of macrophages observed in HIV-infected patients. Professional illustration by Patrick Lane, ScEYEnce Studios.

HIV-1 infection of macrophages, through the expression of the HIV-1–derived protein Nef, pushes macrophages to adopt the “mesenchymal” mode of migration through effects upon the src-family kinase Hck and a downstream effector, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein (WASP). Migratory macrophages that employ the mesenchymal mode are better able to invade dense extracellular matrix and tissues. Results from Vérollet et al provide a mechanistic understanding of the increased infiltration of macrophages observed in HIV-infected patients. Professional illustration by Patrick Lane, ScEYEnce Studios.

Cure of HIV infection, defined as the eradication of HIV from infected patients, has not yet been achieved. Although highly active antiretroviral therapy (HA-ART) has been extraordinarily effective at reducing the morbidity and mortality of HIV infection, HA-ART does not remove latent virus from all cellular reservoirs.2 Macrophages residing in tissues are potential cellular reservoirs that could contribute to the difficulty in eradicating HIV infection.3 Furthermore, invasion of tissues by HIV-laden macrophages may contribute to HIV-associated pathologies. Monocyte/macrophage infiltration of the central nervous system correlated with HIV-associated dementia (HIV-D) and encephalitis.4 Patients with HIV-D also exhibited greater macrophage infiltration of other tissues, including liver, lymph node, and spleen. A mechanistic understanding of the biochemical underpinnings of macrophage tissue invasion during HIV infection may be essential to developing HIV cures.4

Macrophage infiltration of tissues is enhanced by the adoption of the mesenchymal mode of migration. Vérollet et al now show that one of the many ways HIV subverts physiological processes to enable its own survival is by altering the choice of migratory mode to promote tissue invasion of HIV-infected macrophages.1 To place the results of Vérollet et al into context, I will briefly review cellular migratory modes. Migrating cells employ different modes of movement depending on the extracellular environment they are traversing.5 The different modes are classified according to cellular morphologies, molecular signaling pathways, and generation of propulsive vs traction forces.5,6 The best-studied mode of migration is that of polarized cells crawling over the surface of coverslips, or two-dimensional (2D) migration. Most widely modeled in gliding fibroblasts, 2D migration is characterized by Rac-mediated lamellipodial formation at the leading edge and uropod formation at the rear. Requirements for cellular migration in three-dimensional (3D) tissue environments in vivo may vary from those observed in 2D. 3D migration has been divided into two modes, termed amoeboid and mesenchymal. The amoeboid mode is characterized by the movement of rounded cells that do not form strong focal adhesions or stress fibers. Cells employing the amoeboid mode generate propulsive, rather than traction, forces. Amoeboid migration is integrin independent and very rapid, enabling speeds of up to 10 μm/min. Finally, amoeboid migration is not associated with proteolysis of extracellular matrix.5 Lymphocytes moving through lymph nodes exclusively use the amoeboid mode.

In contrast, macrophages can opt to move in either the amoeboid or mesenchymal mode of migration. Cells employing the mesenchymal mode adopt an elongated or spindly appearance.5 The mesenchymal mode is associated with stronger, integrin-based sites of adhesion that anchor the cells to extracellular matrix and enable the generation of cellular traction forces. Mesenchymal movement is slower, with ranges of 0.1 to 1 μm/min, but is associated with proteolysis of surrounding extracellular matrix and supports movement through dense tissues. To support mesenchymal migration, macrophages generate podosomes, specialized integrin-based adhesion structures that quickly remodel over the course of minutes.5 Podosomes contain integrin-binding proteins, such as vinculin and talin, signaling kinases such as the src-family kinase Hck, and actin-binding proteins such as cortactin. Previous work from the group of Maridonneau-Parini has explored the regulatory role of the kinase Hck in podosome formation.7

In this elegant study, Vérollet et al now provide clear evidence that HIV infection pushes macrophages into choosing the mesenchymal mode of migration (see figure).1 Infection with HIV lacking the viral protein Nef did not result in a similar increase in cells adopting the mesenchymal mode, demonstrating that Nef expression was necessary for the phenotype. A shift toward mesenchymal migration promoted the invasion of Matrigel by infected macrophages, an in vitro model of tissue infiltration. Forced overexpression of Nef in macrophages in a transgenic mouse resulted in increased tissue infiltration by macrophages, providing a physiologically relevant correlate of the in vitro findings. The shift toward mesenchymal migration correlated with increased podosome formation and stability and increased matrix degradation. The authors conclude their study by demonstrating that Nef exerts effects upon actin rearrangements via the kinase Hck and the actin regulator WASP. This study thus links prior work showing that Nef binds Hck through its SH3 domain8 and work demonstrating that Hck modulates podosome formation7 to reveal a novel mechanistic understanding of how HIV infection may drive macrophages into tissues, creating a hidden cellular reservoir of virus (see figure).

This study raises several significant questions that offer opportunities for further research. Although some patients with HIV-associated pathology clearly exhibit an increased burden of HIV-laden macrophages in visceral organs,4 it is not yet known whether macrophages form a clinically significant reservoir in all HIV-infected patients, including elite controllers. Furthermore, the current study relies upon a model of tissue macrophage development in which circulating monocytes migrate from the bloodstream into peripheral tissues, differentiating into macrophages and taking up long-term residence in tissues.1 While this model may accurately represent the life history of inflammatory macrophages, other tissue-resident macrophages, including microglia and liver Kupffer cells, are not continually replenished by circulating monocytes.9 Instead, some tissue-resident macrophage subsets arise from yolk sac precursors during embryonic development and autoregenerate without drawing upon the pool of circulating monocytes.9 Whether HIV infection exerts similar effects upon long-lived tissue-resident macrophages as upon inflammatory macrophages remains an open question. Finally, no current clinically employed therapies for HIV-infected patients target HIV-infected macrophages residing in visceral organs. It is not even clear whether concentrations of commonly used HA-ART regimens achieve inhibitory levels in macrophages residing in the liver, central nervous system, or other relevant tissue type.10 The results from Vérollet et al thus highlight the formidable challenges HIV infection still presents to researchers, clinicians, and patients battling to overcome it.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author has no financial conflicts-of-interest to disclose.