To the editor:

We have read with great interest the “Perspectives” article by Steinberg et al in the January 23, 2014, edition of Blood.1 The authors present a mathematical model that implies that the critical content of fetal hemoglobin (HbF) required to prevent polymerization of sickle hemoglobin is higher than the threshold HbF content that renders an erythrocyte detectable as an “F-cell” on immunofluorescent staining by flow cytometry. This would lead to a hypothesis that only a subset of F-cells are resistant to hypoxia-induced sickling. We obtained data from a new imaging flow cytometry assay that can qualitatively support this general principle, although with clear assay limitations that don’t permit us to address quantitatively the predictions of Steinberg et al in detail. These new results show that intracellular HbF is a major factor influencing sickling, but it is clearly not the only factor.

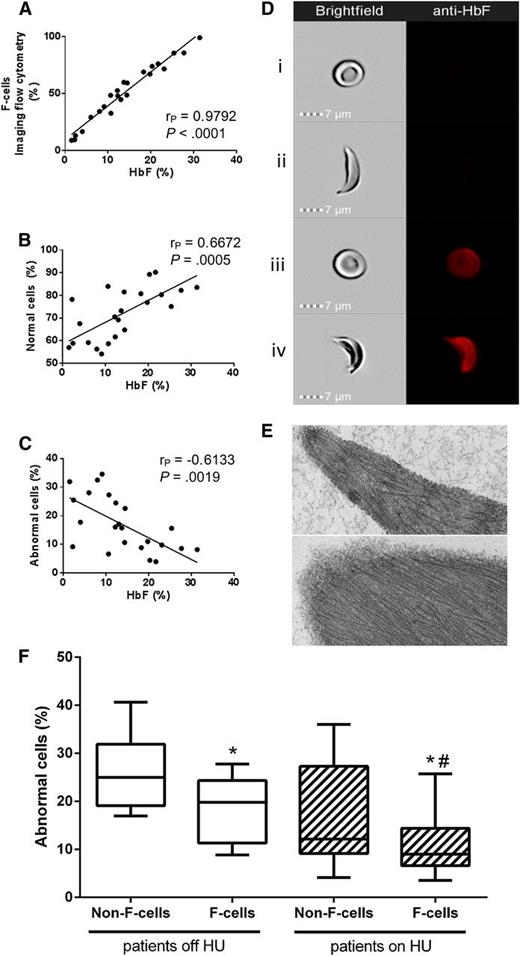

We investigated the influence of HbF content on sickling at the individual cell level through our recently developed Sickle Imaging Flow Cytometry Assay (SIFCA), a robust, reproducible sickling assay.2 We developed an enhanced version of SIFCA that allows simultaneous analysis of both intracellular expression of HbF and morphological features of each red blood cell (RBC). Peripheral venous blood samples were collected with written consent from 22 adult sickle cell anemia (SCA) patients (8 off and 14 on hydroxyurea, median HbF 10.7% and 18.3%, respectively) with a wide HbF range (1.5% to 33.0%). We subjected 1% RBC suspensions to deoxygenation for 2 hours at 2% oxygen followed by fluorescent labeling against HbF. Images from 20 000 cells were obtained by imaging flow cytometry (ImageStreamX Mk II; Amnis Corporation), allowing combined analysis of shape change and HbF expression for each RBC. We confirmed previous observations3 using conventional flow cytometry that F-cell count significantly correlates with percent HbF determined by HPLC (Figure 1A). F-cell count by SIFCA correlated highly with conventional F-cell flow cytometry by an independent Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments–certified facility (r2 = 0.9976, 95% CI 0.9861-0.9996, P < .0001, data not shown). SIFCA yields automated determination of the percentage of “normal cells,” which remain biconcave discs, and of “abnormal cells,” which change their shape on hypoxic incubation, including the majority of sickled cells. As expected, the HbF percentage correlated positively and negatively with the percentage of normal and abnormal cells, respectively (Figure 1B-C).

Imaging flow cytometry documents incomplete resistance of human sickle F-cells to ex vivo hypoxia-induced sickling. (A) HbF in the hemolysate correlates positively with the percentage of F-cells detected by SIFCA. HbF protective effect against sickling is shown by a positive correlation with the percent of cells that remain in normal shape after deoxygenation (B), and an opposite correlation with the percent of cells that become sickled (C). Sample images acquired by the imaging flow cytometer show simultaneous brightfield images (left column) and fluorescence of an anti-HbF-PE antibody (right column) in a normal non-F-cell (Di), sickled non-F-cell (Dii), normal F-cell (Diii), and a sickled F-cell (Div). (E) Transmission electron microscopy of RBCs enriched by fluorescence-activated cell sorting was performed to confirm that sickled cells contained similar fibers corresponding to hemoglobin S polymers regardless of whether they were non-F-cells (top) or F-cells (bottom). Bar = 100 nm. Images acquired with a JEM1400 electron microscope (JEOL) equipped with an AMT XR-111 digital camera (Advanced Microscopy Techniques Corporation). Image Adjust-Levels and Image Adjust Brightness functions in Photoshop Creative Suite 6 software (Adobe Systems Corporation) were used to equalize the densities in both images. (F) Non-F-cells sickled more than F-cells in both patients off hydroxyurea (left side, *P = .0014, paired Student t test) and on HU (right side, *P = .0057, paired Student t test), but cells from treated patients sickle less than from untreated patients (Mann-Whitney test, #P = .0197 for F-cells from patients off HU compared with on HU, P = .0501 for comparison between non-F-cells).

Imaging flow cytometry documents incomplete resistance of human sickle F-cells to ex vivo hypoxia-induced sickling. (A) HbF in the hemolysate correlates positively with the percentage of F-cells detected by SIFCA. HbF protective effect against sickling is shown by a positive correlation with the percent of cells that remain in normal shape after deoxygenation (B), and an opposite correlation with the percent of cells that become sickled (C). Sample images acquired by the imaging flow cytometer show simultaneous brightfield images (left column) and fluorescence of an anti-HbF-PE antibody (right column) in a normal non-F-cell (Di), sickled non-F-cell (Dii), normal F-cell (Diii), and a sickled F-cell (Div). (E) Transmission electron microscopy of RBCs enriched by fluorescence-activated cell sorting was performed to confirm that sickled cells contained similar fibers corresponding to hemoglobin S polymers regardless of whether they were non-F-cells (top) or F-cells (bottom). Bar = 100 nm. Images acquired with a JEM1400 electron microscope (JEOL) equipped with an AMT XR-111 digital camera (Advanced Microscopy Techniques Corporation). Image Adjust-Levels and Image Adjust Brightness functions in Photoshop Creative Suite 6 software (Adobe Systems Corporation) were used to equalize the densities in both images. (F) Non-F-cells sickled more than F-cells in both patients off hydroxyurea (left side, *P = .0014, paired Student t test) and on HU (right side, *P = .0057, paired Student t test), but cells from treated patients sickle less than from untreated patients (Mann-Whitney test, #P = .0197 for F-cells from patients off HU compared with on HU, P = .0501 for comparison between non-F-cells).

Fluorescent labeling of HbF allowed us to discriminate non-F-cells (Figure 1Di-ii) from F-cells (Figure 1Diii-iv), and analyze their shape as captured in the brightfield images. The images confirmed the prediction that some RBCs with detectable HbF content still sickle (Figure 1Div), and also identified RBCs that are resistant to sickling despite no detectable HbF (Figure 1Dii). The percentage of non-F-cells sickling on deoxygenation was significantly higher than among F-cells (20.08% [95% CI 15.56-24.60] vs 13.44% [95% CI 10.21-16.68], P < .0001). This difference was statistically significant both in patients not taking HU and in treated patients (Figure 1F). F-cells from patients on HU sickled significantly less than F-cells from patients off HU, and the same difference was borderline significant when comparing non-F-cells from patients on HU with those off HU.

Our observations support that the threshold used for detection of F-cells is not the same threshold that defines protection against sickling. Similar to previous investigators, we also have found that the very high concentration of intraerythrocytic hemoglobin poses a difficult challenge in achieving the antigen saturation with anti-γ-globin antibody that is necessary to measure accurately the amount of HbF per F-cell,4 which will be needed ultimately to test fully the mathematical modeling predictions of Steinberg et al. Differential RBC susceptibility of non-F-cells to sickling between patients on or off HU also supports the existence of additional beneficial mechanisms of HU other than HbF induction.4 The identification of factors besides HbF that modulate sickle hemoglobin polymerization may help in the design of novel therapies for HU-resistant SCA patients.

Authorship

Contribution: K.Y.F., E.J.v.B., L.S., L.G.M., and R.S. performed sample processing and flow cytometry experiments with supervision of J.P.M. and G.J.K.; J.S.N. enrolled patients and procured samples; D.A.H. and C.A.B. performed electron microscopy processing, imaging and developed related figures with supervision of M.P.D.; K.Y.F., J.P.M., and G.J.K. designed the study; K.Y.F. and G.J.K. performed data analysis and drafted the manuscript; and all authors reviewed and edited the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Gregory J. Kato, Department of Medicine, Division of Hematology-Oncology, and the Heart, Lung, Blood and Vascular Medicine Institute, University of Pittsburgh, 200 Lothrop St, BST E1240, Pittsburgh, PA 15261; e-mail: katogj@upmc.edu.