Abstract

Background: Recurrent mutations in >100 different genes have been described in AML, but the clinical relevance of most of these alterations has not been defined. Moreover, high-throughput sequencing techniques revealed that AML patients (pts) may harbor multiple, genetically related disease subclones. It is unclear whether clonal heterogeneity at diagnosis also associates with clinical characteristics or outcomes. To address these questions, we set out to characterize a relatively large, uniformly treated patient cohort for mutations in known and putative AML driver genes.

Patients and Methods: We studied pretreatment blood or bone marrow specimens from adult AML pts who received high-dose cytarabine-based induction chemotherapy within the German multicenter AMLCG-2008 trial. Sequence variants (single nucleotide variants and insertions/deletions up to approx. 150bp) in 70 genes known to be mutated in AML or other hematologic neoplasms were analyzed by multiplexed amplicon resequencing (Agilent Haloplex; target region, 321 kilobases). Sequencing was performed on an Illumina MiSeq instrument using 2x250bp paired-end reads. A variant allele frequency (VAF) threshold of 2% was set for mutation detection, corresponding to heterozygous mutations present in 4% of cells in a specimen. Variants were classified as known/putative driver mutations, variants of unknown significance, or known germline polymorphisms based on published data (including dbSNP, the Catalogue Of Somatic Mutations In Cancer [COSMIC] and The Cancer Genome Atlas [TCGA]). In patients with more than one single nucleotide variant, the chi square test was used assess if the observed VAFs, adjusted for ploidy, were compatible with the presence of a single clone.

Results: Material for genetic analyses was available for 280 of the 396 participants (71%) enrolled on the AMLC-2008 trial. To date, analyses have been completed for 248 pts (130 male, 118 female; median age, 54y; range 19-81y). Updated results for the entire cohort will be presented at the meeting. Mean coverage of target regions was >600-fold, and on average, 98.2% of target bases were covered >30-fold.

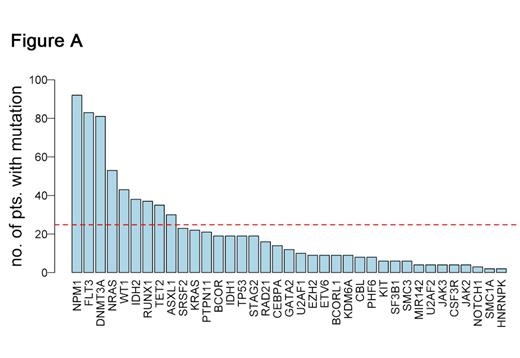

We detected a total of 914 mutations in 46 genes, including 37 genes mutated in >1 patient (Fig. A). Nine genes (NPM1, FLT3, DNMT3A, NRAS, WT1, IDH2, RUNX1, TET2 and ASXL1) were mutated in >10% of patients (red dashed line in Fig. A). We found a median of 4 mutations per patient (range: 0-10). Of note, only 1 patient had no detectable mutation and no abnormality on cytogenetic analysis. Patients with Intermediate-risk cytogenetics according to the MRC classification harbored a higher number of driver gene mutations (median, 4) compared to patients with MRC Favorable (median, 2 mutations) or Unfavorable (median, 3 mutations) cytogenetics (P<.001).

When analyzing patterns of co-occurring and mutually exclusive mutations, we confirmed well-known associations (e.g., between CEBPA and GATA2 mutations) and identified novel pairs of mutations that frequently occur in combination and, to our knowledge, have not yet been reported in AML (e.g., ASXL1/STAG2, SRSF2/STAG2). These findings may guide functional studies on the molecular mechanisms of leukemogenesis.

We found evidence for clonal heterogeneity in 129 (52%) of 248 pts, based on the presence of mutations with significantly (P<.001) different VAFs within the same sample. Our analyses reveal differences in allele frequencies between different AML driver genes. Mutations can be grouped into "early" events that often are present in the founding clone, and "late" events which frequently appear to be restricted to subclones (Fig. B).

Conclusion: Targeted sequencing allowed detection of mutations affecting a panel of known and putative AML driver genes in clinical specimens with high sensitivity. Our data from the AMLCG-2008 patient cohort reveal novel patterns of cooperating gene mutations, and show that the presence of subclonal driver mutations is a frequent event in AML pts. Differentiating between "founding clone" mutations, and subclonal mutations that typically occur later in the disease has implications for choosing targeted therapies aimed at disease eradication.

No relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal