Key Points

FOXO1 directly activates PRDM1α, the master regulator of PC differentiation, and it enriches a PC signature in cHL cell lines.

PRDM1α is a tumor suppressor in cHL.

Abstract

The survival of classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL) cells depends on activation of NF-κB, JAK/STAT, and IRF4. Whereas these factors typically induce the master regulator of plasma cell (PC) differentiation PRDM1/BLIMP-1, levels of PRDM1 remain low in cHL. FOXO1, playing a critical role in normal B-cell development, acts as a tumor suppressor in cHL, but has never been associated with induction of PC differentiation. Here we show that FOXO1 directly upregulates the full-length isoform PRDM1α in cHL cell lines. We also observed a positive correlation between FOXO1 and PRDM1 expression levels in primary Hodgkin-Reed-Sternberg cells. Further, we show that PRDM1α acts as a tumor suppressor in cHL at least partially by blocking MYC. Here we provide a link between FOXO1 repression and PRDM1α downregulation in cHL and identify PRDM1α as a tumor suppressor in cHL. The data support a potential role for FOXO transcription factors in normal PC differentiation.

Introduction

Classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL) differs from other B-cell lymphomas by a unique phenotype of the malignant cells of cHL, Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg (HRS) cells, characterized by loss of the B-cell program and by the formation of a reactive infiltrate harboring these cells.1 The repression of the B-cell program in HRS cells is characterized by downregulation of critical B-cell transcription factors,2 including BCL6.3 The oncogenic program of cHL is based on the constitutive activation of JAK/STAT, NF-κB, ERK, and PI3K/AKT pathways.4-7 Ultimate targets of these pathways are the protooncogenic transcription factors MYC and IRF4.8,9

Of note, NF-κB, STAT3, and IRF4 converge to induce plasma cell (PC) differentiation in normal B cells by upregulation of the PC master transcription factor PRDM1/BLIMP-1.10-12 Surprisingly, HRS cells express only low levels of PRDM1 and other PC markers.3,13

PRDM1 acts as a tumor suppressor in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the activated B-cell type (ABC-DLBCL), whose oncogenic program resembles that of cHL, including dependency on constitutive NF-κB and JAK-STAT activation and high expression of IRF4.1,8,14,15 Of note, NF-κB activation in B cells results in the development of lymphomas only when Prdm1 is deleted.16

We found that FOXO1, which is highly expressed in B cells and in different types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, is downregulated in cHL. Overexpression of a constitutively active FOXO1 protein induces growth arrest and apoptosis in cHL cell lines.17 FOXO1 belongs to the forkhead box (Fhbox) family of transcription factors that regulates different physiological processes including cell death, differentiation, and oxidative stress.18 FOXO1 plays a central role in the early stages of B-cell differentiation,19 and it is essential for the expression of B-cell–specific genes such as BCL6, AICDA, and RAG1/2.20,21 Of note, FOXO1 modulates the activity of the transcription factors STAT3 and NF-κB, which are critical components of the cHL oncogenic program.22-25

Therefore, we hypothesized that FOXO1 repression might be essential for the establishment of the oncogenic program and for the specific phenotype of cHL. By using gene expression profiling (GEP) and functional studies, we analyzed the influence of FOXO1 reactivation on cHL cell lines. We identified PRDM1α as a direct target of FOXO1 and as a tumor suppressor in cHL.

Material and methods

For detailed description of all methods, see the supplemental data available on the Blood Web site.

Cell lines and culture conditions

The L428, L1236, KM-H2, SUP-HD1, and U-HO1 cHL cell lines stably expressing constitutively active inducible FOXO1-variant FOXO1(A3)ER were previously described.17

Expression vectors and lentiviral transduction

Open reading frames of PRDM1α and PRDM1β were cloned into the lentiviral vector SF-LV-cDNA-EGFP.26

Lentiviral particles were generated by HEK-293T cells that were cotransfected with expression vector, packaging, and envelope plasmids. cHL cell lines were transduced by supernatants containing lentiviral particles using spinoculation.

Luciferase reporter assay

Promoter regions of PRDM1α and PRDM1β were cloned into pGL4.20 (Promega). Luciferase activity was measured using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega).

RNA interference

Cells were transfected with specific siRNA or negative control siRNA at a concentration of 2 µM using Amaxa Nucleofector and nucleofection buffer “V” (Lonza). Knockdown efficiency was analyzed by immunoblot at different time points.

Flow cytometry and cell sorting

Growth dynamics of cHL cell lines transduced with a lentiviral vector coexpressing GFP were monitored by flow cytometry (FACSCalibur, BD Biosciences). For biochemical analysis, transduced GFP+ cells were sorted using a FACSAria (BD Biosciences). Sorting was performed by the Core Facility “Fluorescent Activated Cell Sorting,” Medical Faculty of Ulm, Germany.

Proliferation of cells transfected with MYC siRNA was assessed by counting viable cells at indicated time points using a Vi-Cell XR device (Beckman Coulter).

Cell-cycle analysis was performed as described in the supplemental Experimental Procedures. Cell-cycle distribution was measured by flow cytometry and was analyzed with help of ModFit LT Version 2.0 software (Verify Software House, Topsham, ME).

Q-RT-PCR and immunoblot analysis

Total RNA was extracted, cDNA was synthesized, and gene expression was analyzed by SYBR-green or TaqMan Q-RT-polymerase chain reaction (PCR). All experiments were repeated at least 3 times. For protein analysis, cells were lyzed in Laemmli buffer containing 6M urea, and they were separated by SDS-PAGE. The proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane by wet blotting and they were probed with specific antibodies.

Direct sequencing and promoter methylation analysis

For mutational analysis of PRDM1, cDNA was amplified with specific primer pairs as described,27 and the amplicons were directly sequenced by GATC Biotech. Methylation analysis of PRDM1α and PRDM1β promoters was performed by pyrosequencing as described previously.28 HRS cells were isolated by microdissection as described.28

The samples were drawn from our archive of frozen tissues and were pseudonymized to comply with the German law for ethical use of archival tissue for clinical research (Deutsches Ärzteblatt 2003; 100 A1632). Approval for these studies was obtained from the University of Ulm ethics board. Research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Electromobility shift assay

The DNA-binding domain of FOXO3, Fhbox, was cloned into pFLAG-CMV-2, giving rise to a protein that was FLAG-tagged at its N terminus. Nuclear extracts of HEK-293T cells expressing Fhbox were prepared as described.29 Oligonucleotide probes were used containing wild-type or mutated FOXO1-binding sites flanked by PRDM1α promoter region. Briefly, equal amounts of nuclear extract were incubated with radioactively labeled probes. For supershift experiments, we used anti-Flag antibody (Sigma). Anti-IRS2 antibody (Santa Cruz) was used as control.

Complexes were separated on a prerun 12% polyacrylamide gel in 0.4X TBE at 180 V for 3 hours.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

L428 cells transfected with vectors expressing bFOXO1 (FOXO1 tagged by a biotin ligase recognition signal) and BirA or empty vector (EV) and BirA were used. Briefly, cells were crosslinked, lysed, and sonicated to shear chromatin. Samples were then precleared with blocked protein A agarose beads (Millipore) for 1 hour at 4°C and were subsequently incubated with Streptavidin MagneSphere Paramagnetic Particles (Promega) for 3 hours at 4°C. Particles were washed with 2% SDS and a LiCl buffer. To isolate DNA, a 10% Chelex-100 bead-suspension (Bio-Rad) was added to the beads, followed by the addition of proteinase K and RNase A. Supernatant was collected by centrifugation, and DNA was purified using a PCR purification kit (Qiagen). Input samples were reverse-crosslinked in a 0.2 M NaCl solution and by proteinase K treatment, and they were incubated at 62°C for 2 hours. DNA was purified using the PCR purification kit from Qiagen and was analyzed by Q-PCR. For details see the supplemental Experimental Procedures. To quantify chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) data, we calculated fold enrichment of the PRDM1α promoter regions over the control Chr 12 region (R). For this, we first normalized ChIP DNA to input DNA by using the following formula: Ri = 2(Ctinput-CtChIP). We then calculated fold enrichment of PRDM1α promoter regions in samples transfected with bFOXO1 compared with EV: RF/EV = Ri(bFOXO1)/Ri(EV). Next, we calculated R using the formula R = RF/EV PRDM1 / RF/EV CH12.

GEP

Described earlier were the cHL cell lines KM-H2, L428, L1236, U-HO1, and SUP-HD1 that were stably expressing constitutively active mutant of human FOXO1, which was fused in frame with the mutant-mouse estrogen receptor ligand-binding domain (FOXO1(A3)ER).17 To induce nuclear translocation of FOXO1(A3)ER, cells were treated with 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT) at a concentration of 200 nM or by a vehicle (ethanol). A total of 24 hours after treatment, total RNA was extracted and gene expression profiles were analyzed using Human Gene 1.0 ST Affymetrix GeneChip arrays as already described.28 Probe-level data were obtained using the robust multichip average normalization algorithm. To find genes regulated by FOXO1 activation, we used fold change cutoff of 2 and Benjamini and Hochberg correction (P < .05). The analysis of differentially expressed genes was achieved with help of GeneSifter microarray data analysis software (www.genesifter.net, PerkinElmer; Waltham, MA). For all cell lines, 2 biological replicates were analyzed. Microarray data have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information’s Gene Expression Omnibus (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gds) under accession number GSE29545.

Correlation analysis

To investigate the correlation between expression levels of genes, we reanalyzed gene expression profiles of microdissected HRS cells from 29 cases. GEP data were mined from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/; GSE39133.4 The following probe sets (Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array) were used for correlation analysis: FOXO1 - 202724_s_at; MYC - 202431_s_at; PRDM1 - 228964_at; REL - 206036_s_at; JAK2 - 205842_s_at.

For correlation analysis we used Prism 6 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

Results

FOXO1 partially activates the PC program in cHL cell lines

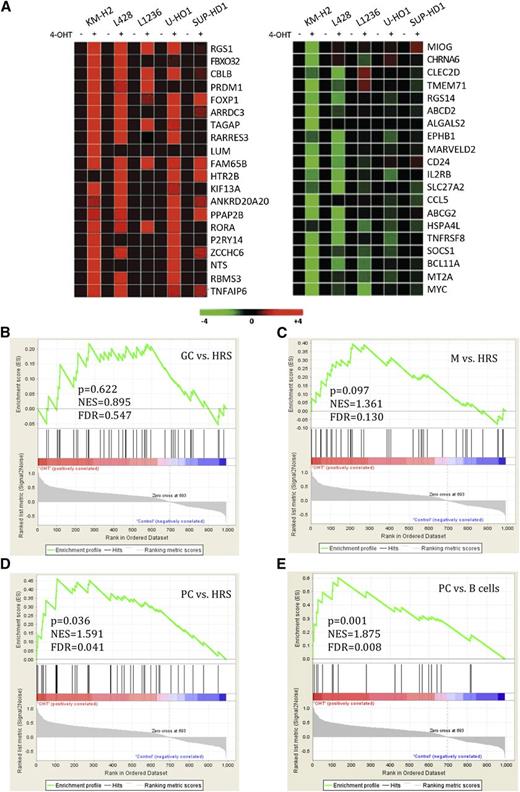

To investigate the influence of FOXO1 activation on the transcriptomes of the 5 B-cell cHL cell lines, we used GEP. The cell lines expressed the constitutively active variant of FOXO1 fused in frame to the ligand-binding domain of the estrogen receptor FOXO1(A3)ER. The fusion protein was activated by the administration of 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT).17 Given that B-cell–specific and tumor suppressor genes in cHL are often inactivated by epigenetic silencing or by genomic mutations, we did not expect that FOXO1 would induce its target genes in all cell lines.30,31 Therefore, we used a threshold of 2 to filter out 1133 probe sets modulated at least in 1 cell line (supplemental Table 1). Among the top 20 upregulated genes, we identified FOXP1, which is a FOXO1 target gene highly expressed in naïve and memory B cells32 and downregulated in cHL.33 Surprisingly, PRDM1/BLIMP-1, the master regulator of PC differentiation, was also upregulated (Figure 1A).34 Intriguingly, among the top 20 downregulated genes were the PRDM1 repression target MYC,35,36 whose constitutive expression is critical for the survival of cHL cell lines,8 and TNFRSF8/CD30, a hallmark of cHL.37 As HRS cells arise from germinal center (GC) or post-GC B cells,38 we asked whether FOXO1 reactivation specifically reprograms the molecular signature of cHL cell lines toward a GC, a memory B cell, or a PC phenotype. To clarify, we used gene set enrichment analysis.

FOXO1 significantly activates PC signature in cHL cell lines. cHL cell lines stably expressing FOXO1(A3)ER were harvested 24 hours after treatment with 4-OHT or with vehicle. (A) Heat-map representation of the top 20 upregulated (red) and downregulated (green) genes. (B-E) Gene set enrichment analysis of genes modulated by FOXO1 in cHL cell lines. The enrichment score was calculated by a running sum statistic (green line). It increases when a gene of a gene signature (vertical black bar) is encountered by walking down the ranked list obtained by our GEP. The higher the correlation of the gene with the phenotype, the higher the increment.34 (B) FOXO1 does not significantly enrich GC signature in cHL cell lines. (C) Enrichment of memory B-cell (M) signature. (D) Enrichment of signature of genes expressed fivefold higher in PCs than in HRS cells. (E) Enrichment of the PC signature. FDR, false discovery rate; NES, normalized enrichment scores.

FOXO1 significantly activates PC signature in cHL cell lines. cHL cell lines stably expressing FOXO1(A3)ER were harvested 24 hours after treatment with 4-OHT or with vehicle. (A) Heat-map representation of the top 20 upregulated (red) and downregulated (green) genes. (B-E) Gene set enrichment analysis of genes modulated by FOXO1 in cHL cell lines. The enrichment score was calculated by a running sum statistic (green line). It increases when a gene of a gene signature (vertical black bar) is encountered by walking down the ranked list obtained by our GEP. The higher the correlation of the gene with the phenotype, the higher the increment.34 (B) FOXO1 does not significantly enrich GC signature in cHL cell lines. (C) Enrichment of memory B-cell (M) signature. (D) Enrichment of signature of genes expressed fivefold higher in PCs than in HRS cells. (E) Enrichment of the PC signature. FDR, false discovery rate; NES, normalized enrichment scores.

By applying a signature comprising genes upregulated in GC B cells in comparison with microdissected HRS cells (supplemental Table 2), we found that although some genes of the GC signature (BCL6, AICDA, BACH2, GCET2) were upregulated, enrichment of the GC signature was not statistically significant (Figure 1B and supplemental Table 3). Interestingly, the memory B-cell signature was significantly enriched (FDR < 0.25). In particular, FOXP1 was on the top of the core set of genes (Figure 1C). To clarify whether induction of PRDM1 can be attributed to PC differentiation, we applied a signature that comprises genes whose expression is fivefold higher in PCs compared with HRS cells (supplemental Table 2). Enrichment of the PC signature was statistically significant (Figure 1D and supplemental Table 3). To corroborate the enrichment of PC-specific genes, we used a signature that comprises genes expressed threefold higher in PCs as compared with other B-cell subtypes (supplemental Table 2). This signature had an even higher enrichment score (Figure 1E and supplemental Table 3).

Thus, FOXO1 reactivation significantly enriched a PC-associated signature in cHL cell lines.

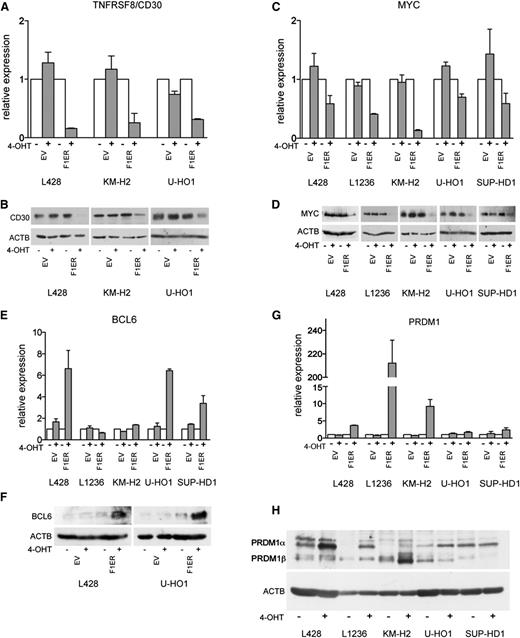

Validation of GEP data

Next, we validated the results of GEP. We first assessed the modulation of genes known to contribute to the oncogenic program of cHL. Consistent with GEP data, FOXO1 downregulated TNFRSF8 mRNA and protein levels in KM-H2, L428, and in U-HO1 cells (Figure 2A-B). In L1236 and SUP-HD1 cell lines, which do not express TNFRSF8 or express it at very low levels,39,40 TNFRSF8 was not further downregulated (data not shown). MYC downregulation was confirmed in cHL cell lines by Q-RT-PCR and immunoblot (Figure 2C-D).

Validation of GEP data. (A-H) Indicated genes were validated with Q-RT-PCR and immunoblot. cHL cell lines expressing FOXO1(A3)ER (F1ER) or EV were treated with 4-OHT for 24 hours. Q-RT-PCR data were analyzed by the comparative Ct method. RPL13A was used as reference. mRNA expression levels are shown as fold change relative to untreated cells. A 2-sided Student t test was used to estimate statistical significance between treated and untreated samples. For TNFRSF8, MYC, and PRDM1, P values were <.05 in all cell lines. For BCL6, P values were <.05 except for SUP-HD1 (P = .06). For immunoblot, ACTB was used as loading control.

Validation of GEP data. (A-H) Indicated genes were validated with Q-RT-PCR and immunoblot. cHL cell lines expressing FOXO1(A3)ER (F1ER) or EV were treated with 4-OHT for 24 hours. Q-RT-PCR data were analyzed by the comparative Ct method. RPL13A was used as reference. mRNA expression levels are shown as fold change relative to untreated cells. A 2-sided Student t test was used to estimate statistical significance between treated and untreated samples. For TNFRSF8, MYC, and PRDM1, P values were <.05 in all cell lines. For BCL6, P values were <.05 except for SUP-HD1 (P = .06). For immunoblot, ACTB was used as loading control.

Upregulation of the GC-specific FOXO1 targets BCL6 (Figure 2E-F) and AICDA (supplemental Figure 1A-B), as well as the GC program genes BACH2 and GCET2, was validated by Q-RT-PCR or immunoblot (supplemental Figure 1C-D).

Because FOXO1 induced genes of a PCs signature, we validated upregulation of PRDM1, the master regulator of PC differentiation. Consistent with GEP, a considerable induction of PRDM1 mRNA was observed in L1236, KM-H2, and L428 cells, whereas only a slight upregulation was seen in SUP-HD1 and U-HO1 (Figure 2G). Further, we verified PRDM1 induction at the protein level using immunoblot (Figure 2H; see also next section). We also validated upregulation of the PC signature gene RGS1 in all cell lines (supplemental Figure 1E).

Taken together, our results indicate that FOXO1 repression in cHL might contribute to the extinction of the B-cell program, block of PC differentiation, and consequently malignant transformation.

FOXO1 activates PRDM1α in cHL

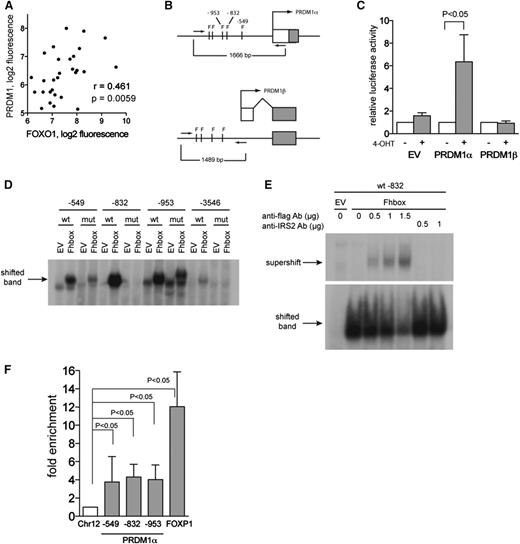

The fact that PRDM1 acts as a tumor suppressor in ABC-DLBCL prompted further investigation of FOXO1-mediated upregulation of PRDM1. We reanalyzed gene expression data of microdissected HRS cells,4 and we observed a positive correlation between FOXO1 and PRDM1 expression (Figure 3A), supporting the notion that FOXO1 is a positive regulator of PRDM1.

FOXO1 directly activates the PRDM1α promoter. (A) Positive correlation between expression levels of FOXO1 and PRDM1 in microdissected HRS cells. p, 1-tailed Student t test; r, Pearson correlation coefficient. Data were mined from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/; GSE39133. (B) Schematic diagram showing the promoter region of PRDM1α and PRDM1β. The FOXO1-binding motif TRTTTAY is indicated as F. The PRDM1β promoter is located within intron 3 of PRDM1α. Promoter regions were amplified using primers indicated as arrows and cloned into pGL4.20 luciferase reporter plasmid. (C) FOXO1 activates PRDM1α promoter. L428 cells expressing FOXO1(A3)ER were transiently transfected with empty pGL4.20 vector or vector containing PRDM1 promoter regions, together with ubi-Renilla as reference vector. A total of 2 hours later, cells were treated or were not treated with 4-OHT. Relative luciferase activity was measured 24 hours after transfection. A total of 3 independent experiments were performed. Data are shown as mean ±SD. P value was determined using Student t test. (D) EMSA indicates DNA-binding activity of FOXO1 to PRDM1α promoter. Nuclear extracts were obtained from HEK-293T cells expressing EV or the FOXO1 DNA-binding domain (Fhbox). The probes used contained wild-type (wt) or mutated (mut) FOXO1-binding motifs flanked by PRDM1α promoter region. Position of motifs is indicated. A representative of 2 independent experiments is shown. (E) Supershift assay using Flag antibody or nonspecific IRS2 antibody confirmed binding of Fhbox to wt probe −832. A representative of 2 independent experiments is shown. (F) FOXO1 binds to the PRDM1α promoter. L428 cells were transfected with bFOXO1 and BirA or with EV and BirA. Twenty-four hours later, cells were harvested and ChIP was performed as described in the “Chromatin Immunoprecipitation” section of the supplemental Experimental Procedures. The tested PRDM1α promoter regions are indicated. A FOXP1 enhancer region was used as positive control. The precipitated chromatin was quantified by Q-PCR. Data are shown as fold enrichment compared with the negative control region located on chromosome 12 (Chr12) (see also supplemental Experimental Procedures, “Chromatin Immunoprecipitation”). A total of 5 independent experiments were performed. Data are shown as the mean ±SD. For FOXP1, results from 4 experiments are shown.

FOXO1 directly activates the PRDM1α promoter. (A) Positive correlation between expression levels of FOXO1 and PRDM1 in microdissected HRS cells. p, 1-tailed Student t test; r, Pearson correlation coefficient. Data were mined from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/; GSE39133. (B) Schematic diagram showing the promoter region of PRDM1α and PRDM1β. The FOXO1-binding motif TRTTTAY is indicated as F. The PRDM1β promoter is located within intron 3 of PRDM1α. Promoter regions were amplified using primers indicated as arrows and cloned into pGL4.20 luciferase reporter plasmid. (C) FOXO1 activates PRDM1α promoter. L428 cells expressing FOXO1(A3)ER were transiently transfected with empty pGL4.20 vector or vector containing PRDM1 promoter regions, together with ubi-Renilla as reference vector. A total of 2 hours later, cells were treated or were not treated with 4-OHT. Relative luciferase activity was measured 24 hours after transfection. A total of 3 independent experiments were performed. Data are shown as mean ±SD. P value was determined using Student t test. (D) EMSA indicates DNA-binding activity of FOXO1 to PRDM1α promoter. Nuclear extracts were obtained from HEK-293T cells expressing EV or the FOXO1 DNA-binding domain (Fhbox). The probes used contained wild-type (wt) or mutated (mut) FOXO1-binding motifs flanked by PRDM1α promoter region. Position of motifs is indicated. A representative of 2 independent experiments is shown. (E) Supershift assay using Flag antibody or nonspecific IRS2 antibody confirmed binding of Fhbox to wt probe −832. A representative of 2 independent experiments is shown. (F) FOXO1 binds to the PRDM1α promoter. L428 cells were transfected with bFOXO1 and BirA or with EV and BirA. Twenty-four hours later, cells were harvested and ChIP was performed as described in the “Chromatin Immunoprecipitation” section of the supplemental Experimental Procedures. The tested PRDM1α promoter regions are indicated. A FOXP1 enhancer region was used as positive control. The precipitated chromatin was quantified by Q-PCR. Data are shown as fold enrichment compared with the negative control region located on chromosome 12 (Chr12) (see also supplemental Experimental Procedures, “Chromatin Immunoprecipitation”). A total of 5 independent experiments were performed. Data are shown as the mean ±SD. For FOXP1, results from 4 experiments are shown.

The PRDM1 gene produces at least 2 proteins. PRDM1α is the full-length form with a PR-domain involved in target gene repression, whereas PRDM1β is the truncated variant with a disrupted PR-domain. PRDM1β still binds to DNA but has a severely impaired ability to repress target genes and thereby is believed to act as a dominant-negative variant.41 The immunoblot showed that FOXO1 differentially regulated these 2 PRDM1 isoforms (Figure 2H). In most cell lines, only PRDM1α was upregulated, except in KM-H2, where PRDM1β was also upregulated.

To investigate further the induction of PRDM1 by FOXO1, we analyzed the PRDM1α and PRDM1β promoters in silico. Promoter regions of both transcriptional variants harbored FOXO-binding motifs (TRTTTAY) (Figure 3B). To investigate the influence of FOXO1 on PRDM1 promoter activity, we used a luciferase reporter assay in L428 cells. FOXO1 activation significantly increased PRDM1α but not PRDM1β promoter activity (Figure 3C).

To investigate the potential of FOXO to bind directly to the PRDM1α promoter, we performed an electromobility shift assay (EMSA). For this, we used nuclear extracts of HEK-293T cells transfected with the highly conserved Fhbox DNA-binding domain of human FOXO (Fhbox) (supplemental Figure 2A). The probes used for the EMSA contained the FOXO-binding motifs within the PRDM1α promoter. Compared with EV, Fhbox resulted in a gel shift when using probes containing the FOXO1-binding motifs at position −549, −832, −953, and −3546 upstream of the PRDM1α transcription start site (Figure 3D). The strongest shift was obtained with probe −832. Scrambling of the FOXO-binding motif strongly decreased complex formation. A supershift assay confirmed specific binding of Fhbox to the FOXO1-binding site at −832 (Figure 3E).

To clarify whether FOXO1 directly binds to the PRDM1α promoter in vivo, we used ChIP. For this, we generated a construct expressing the constitutively active form of FOXO1 tagged by a biotin ligase recognition signal (bFOXO1). Efficient biotinylation by the humanized version of the bacterial biotin ligase BirA42 was confirmed by the pulling down of bFOXO1 with streptavidin magnetic beads (supplemental Figure 2B). Luciferase reporter assays showed that transactivation activity of the tagged construct was not impaired (supplemental Figure 2C). We tested binding of FOXO1 to the promoter regions at −549, −832, and −953 upstream of the PRDM1α start of transcription (see also Figure 3B). Compared with a control gene desert locus on chromosome 12 containing no FOXO1-binding sites, all 3 promoter regions were significantly enriched (Figure 3F). As a positive control, we used a FOXP1 enhancer region where FOXO3 was shown to bind directly.43 Notably, FOXP1 was also upregulated in our GEP (Figure 1A).

Thus, we conclude that PRDM1α is a direct target gene of FOXO1.

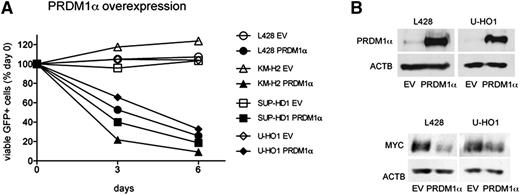

PRDM1α is a tumor suppressor in cHL

To investigate the influence of PRDM1α on the proliferation of cHL cell lines, we transduced cHL cell lines with a lentiviral vector expressing PRDM1α and GFP as a fluorescent marker. Using flow cytometry, we monitored the dynamics of the GFP+ PRDM1α-expressing population (Figure 4A). Compared with EV, the percentage of cells expressing PRDM1α significantly decreased with time in all cell lines. Because MYC repression by PRDM1α is responsible for cell-cycle exit during terminal differentiation,35,36 we measured MYC levels in sorted L428 and U-HO1 cells ectopically expressing PRDM1α or GFP. PRDM1α strongly inhibited MYC expression in L428 and U-HO1 cells (Figure 4B). In summary, our results identify PRDM1α as a tumor suppressor in cHL, and repression of MYC might be involved in the tumor-suppressive effect.

PRDM1α is a tumor suppressor in cHL. (A) PRDM1α is toxic to cHL cell lines. PRDM1α was ectopically expressed in cHL cell lines using the lentiviral SF-LV-cDNA-EGFP vector. Percentage of live GFP+ cells expressing PRDM1α or EV was measured by flow cytometry. Percentage on first day of measurement (day 0) was defined as 100%. The data are shown as mean of 3 independent experiments. P value was determined by a 2-sided Student t test, P < .05. (B) PRDM1α represses MYC in cHL cell lines. L428 and U-HO1 cells were transduced with lentiviral vector expressing PRDM1α or with EV and were sorted 4 to 5 days later. PRDM1α and MYC protein levels were analyzed by immunoblot.

PRDM1α is a tumor suppressor in cHL. (A) PRDM1α is toxic to cHL cell lines. PRDM1α was ectopically expressed in cHL cell lines using the lentiviral SF-LV-cDNA-EGFP vector. Percentage of live GFP+ cells expressing PRDM1α or EV was measured by flow cytometry. Percentage on first day of measurement (day 0) was defined as 100%. The data are shown as mean of 3 independent experiments. P value was determined by a 2-sided Student t test, P < .05. (B) PRDM1α represses MYC in cHL cell lines. L428 and U-HO1 cells were transduced with lentiviral vector expressing PRDM1α or with EV and were sorted 4 to 5 days later. PRDM1α and MYC protein levels were analyzed by immunoblot.

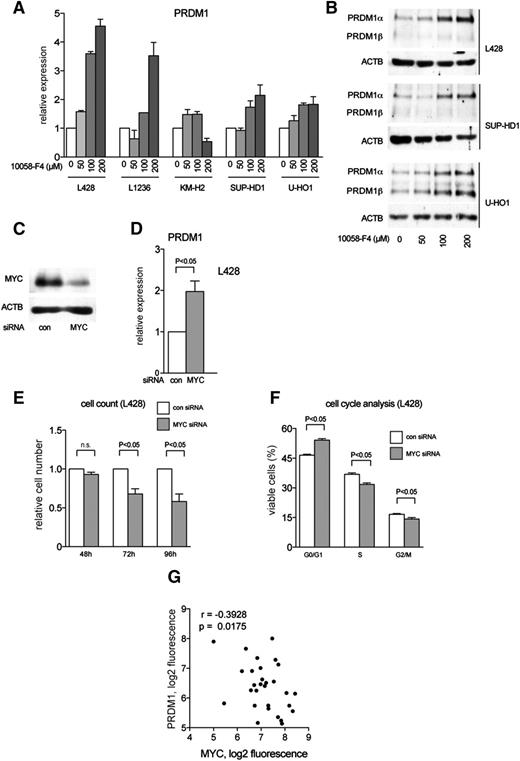

MYC contributes to PRDM1 repression in cHL

One of the most prominent effects of FOXO1 activation in cHL cell lines was repression of MYC. Because MYC and PRDM1α are reciprocally regulated,35,44 we asked whether high MYC expression in cHL contributes to PRDM1α downregulation. To this end, we treated cHL cell lines with the low molecular weight MYC inhibitor 10058-F4. The inhibitor strongly upregulated PRDM1 mRNA and protein expression in a dose-dependent manner in most cHL cell lines (Figure 5A-B). In addition, we used specific siRNA to knock down MYC in L428 cells. Downregulation of MYC protein by about 70% (Figure 5C) led to a twofold increase of PRDM1 mRNA (Figure 5D). The physiological efficacy of MYC downregulation was proved by cell-cycle and cell-proliferation analyses (Figure 5E-F).

MYC represses PRDM1 in cHL. (A-B) cHL cell lines were treated with the small molecular weight MYC inhibitor 10058-F4 for 24 hours. Control cells were treated with equal volumes of DMSO. PRDM1 expression was determined by (A) Q-RT-PCR and (B) immunoblot. (C-F) L428 cells were transiently transfected with control siRNA (con) or siRNA against MYC. (C) Knockdown of MYC was confirmed 48 hours after transfection. (D) PRDM1 expression levels were measured by Q-RT-PCR 24 hours after transfection with siRNA. The experiment was repeated 3 times. The data are shown as mean ±SD. P value was determined using Student t test. (E) L428 cells were counted at indicated time points after transfection with con or MYC siRNA. Two independent experiments were performed. n.s., not statistically significant; P value was determined using Student t test. (F) The effect of MYC knockdown on cell-cycle distribution was measured by propidium iodide staining 48 hours after transfection with control (con) or MYC siRNA. Two independent experiments with 3 technical replicates each were performed. Data are presented as mean ±SD. P value was determined using Student t test. (G) Negative correlation between expression levels of MYC and PRDM1 in microdissected HRS cells from 29 cases. Data were mined from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/; GSE39133. ; p, 1-tailed Student t test; r, Pearson correlation coefficient.

MYC represses PRDM1 in cHL. (A-B) cHL cell lines were treated with the small molecular weight MYC inhibitor 10058-F4 for 24 hours. Control cells were treated with equal volumes of DMSO. PRDM1 expression was determined by (A) Q-RT-PCR and (B) immunoblot. (C-F) L428 cells were transiently transfected with control siRNA (con) or siRNA against MYC. (C) Knockdown of MYC was confirmed 48 hours after transfection. (D) PRDM1 expression levels were measured by Q-RT-PCR 24 hours after transfection with siRNA. The experiment was repeated 3 times. The data are shown as mean ±SD. P value was determined using Student t test. (E) L428 cells were counted at indicated time points after transfection with con or MYC siRNA. Two independent experiments were performed. n.s., not statistically significant; P value was determined using Student t test. (F) The effect of MYC knockdown on cell-cycle distribution was measured by propidium iodide staining 48 hours after transfection with control (con) or MYC siRNA. Two independent experiments with 3 technical replicates each were performed. Data are presented as mean ±SD. P value was determined using Student t test. (G) Negative correlation between expression levels of MYC and PRDM1 in microdissected HRS cells from 29 cases. Data were mined from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/; GSE39133. ; p, 1-tailed Student t test; r, Pearson correlation coefficient.

To estimate the role of MYC in PRDM1α repression in vivo, we reanalyzed GEP data of microdissected HRS cells. In accordance with in vitro data, we found a statistically significant inverse correlation between MYC and PRDM1 (Figure 5G). Thus, our data indicate that MYC contributes to the oncogenic program of cHL by repressing PRDM1α. In turn, FOXO1 repression contributes to enhanced expression of MYC.

Genomic mutations and chromosomal aberrations do not play a major role in PRDM1α downregulation in cHL

To investigate whether genomic alterations in PRDM1α play a role in cHL, we sequenced the PRDM1α coding region in 5 cHL cell lines. Only in the L428 cell line was a missense variant detected, which, however, was not located in a functionally important protein domain (supplemental Table 4). When analyzing microdissected HRS cells from 10 cases, we found no evidence of somatic single nucleotide variants or small insertions/deletions as compared with intratumor T-cell control (data not shown). We further investigated the frequency of chromosomal aberrations at the PRDM1 locus in cHL cell lines and in microdissected HRS cells. We found monoallelic deletions in 2 cell lines and a chromosomal gain in 1 cell line (supplemental Table 5). Similarly, in 18.9% of cases (10 of 53 cases) chromosomal deletions of PRDM1 were detected. However, there was no correlation between PRDM1 copy number and gene expression (supplemental Figure 3). Thus, genomic mutations and chromosomal aberrations do not play a major role in PRDM1α inactivation in cHL.

Promoter hypermethylation and PRDM1β might contribute to PRDM1α inactivation in cHL

Epigenetic factors such as promoter hypermethylation,45 microRNAs,46,47 and enhanced PRDM1β levels48 have been reported to contribute to PRDM1α inactivation in lymphomas.

We assessed the methylation status of PRDM1α promoter CpG islands located in proximity to the transcription start sites (Figure 6A). We found that the PRDM1α promoter was hypermethylated in KM-H2 and in U-HO1 cell lines, but neither in CD19+ B cells (Figure 6B) nor in microdissected HRS cells (Figure 6C). This discovery indicates that methylation seen in the cell lines is either a cell-culture consequence or a late-stage phenomenon, secondary to repression of PRDM1α transcription.

The role of promoter methylation and PRDM1β expression in PRDM1α inhibition. (A) Schematic diagram showing PRDM1α and PRDM1β promoter CpG island (gray horizontal bar). CpG-dinucleotides (vertical lines), amplification primers (forward and reverse arrows) and sequencing (seq) primer at PRDM1α and PRDM1β promoters are depicted. The broken arrow indicates start of transcription. (B) Bisulfite pyrosequencing analysis of PRDM1α and PRDM1β promoter in cHL cell lines and normal tonsillar CD19+ B cells. The methylation intensity is shown by color coding. (C) Bisulfite pyrosequencing analysis of PRDM1α promoter in microdissected HRS cells of 9 cHL cases. (D) PRDM1β is upregulated in cHL cell lines. End point RT-PCR analysis of PRDM1α and PRDM1β expression in cHL and MM cell lines using PRDM1α and PRDM1β specific primers. GAPDH was used as a reference gene. (E) PRDM1β/PRDM1α ratio in cHL and MM cell lines were measured by TaqMan Q-RT-PCR using PRDM1α and PRDM1β specific primers. (F-G) PRDM1β has reduced toxicity to cHL cell lines as compared with PRDM1α. cHL cell lines were transduced with lentiviral SF-LV-cDNA-EGFP vector expressing PRDM1β or EV. (F) PRDM1β protein expression in transduced cell lines is shown by immunoblot. (G) Percentage of live GFP+ cells was monitored over 9 days by flow cytometry as described in Figure 4A. Data are presented as mean of 2 independent experiments.

The role of promoter methylation and PRDM1β expression in PRDM1α inhibition. (A) Schematic diagram showing PRDM1α and PRDM1β promoter CpG island (gray horizontal bar). CpG-dinucleotides (vertical lines), amplification primers (forward and reverse arrows) and sequencing (seq) primer at PRDM1α and PRDM1β promoters are depicted. The broken arrow indicates start of transcription. (B) Bisulfite pyrosequencing analysis of PRDM1α and PRDM1β promoter in cHL cell lines and normal tonsillar CD19+ B cells. The methylation intensity is shown by color coding. (C) Bisulfite pyrosequencing analysis of PRDM1α promoter in microdissected HRS cells of 9 cHL cases. (D) PRDM1β is upregulated in cHL cell lines. End point RT-PCR analysis of PRDM1α and PRDM1β expression in cHL and MM cell lines using PRDM1α and PRDM1β specific primers. GAPDH was used as a reference gene. (E) PRDM1β/PRDM1α ratio in cHL and MM cell lines were measured by TaqMan Q-RT-PCR using PRDM1α and PRDM1β specific primers. (F-G) PRDM1β has reduced toxicity to cHL cell lines as compared with PRDM1α. cHL cell lines were transduced with lentiviral SF-LV-cDNA-EGFP vector expressing PRDM1β or EV. (F) PRDM1β protein expression in transduced cell lines is shown by immunoblot. (G) Percentage of live GFP+ cells was monitored over 9 days by flow cytometry as described in Figure 4A. Data are presented as mean of 2 independent experiments.

In ABC-DLBCL, aberrant expression of PRDM1β has been suggested to promote lymphomagenesis by blocking PRDM1α.48 One study indicated expression of PRDM1β in HL.64 We also noticed that PRDM1β is expressed in cHL cell lines (Figure 2H). In normal B cells, this variant is normally not49 expressed or is only weakly expressed.41 Aberrant PRDM1β expression was confirmed in L428, KM-H2, and U-HO1 cells using end-point RT-PCR (Figure 6D). Expression levels were compared with those of the multiple myeloma (MM) cell line Karpas 707H. MM cell lines and MM cells of patients are known to express PRDM1β at higher levels than normal PCs.50 Q-RT-PCR analysis showed that PRDM1β /PRDM1α mRNA ratios were greater than 1 in KM-H2 and in U-HO1 cell lines (Figure 6E), confirming end-point PCR (Figure 6D) and immunoblot (Figure 2H) data. In the other cell lines, ratios varied between 0.17 and 0.30.

In ABC-DLBCL, the PRDM1β promoter is demethylated.49 Vrzalikova et al found PRDM1β promoter hypomethylation in 3 B-cell cHL cell lines and cHL cases.64 Therefore, we investigated the methylation status of the PRDM1β promoter in 5 cHL cell lines. Indeed, the PRDM1β promoter was hypomethylated in comparison with normal CD19+ B cells. An exception was the L1236 cell line having a PRDM1β promoter methylation pattern similar to CD19+ B cells (Figure 6B). To investigate the effect of PRDM1β on cell proliferation, we ectopically expressed PRDM1β in L428, SUP-HD1, and U-HO1 cells (Figure 6F) using the same lentiviral vector as already described (Figure 4A) and monitored the percentage of PRDM1β-expressing cells (Figure 6G). During a period of 9 days, the percentage of L428 and SUP-HD1 cells expressing PRDM1β was reduced only marginally. The results indicate that PRDM1β has a minor antiproliferative activity in cHL in comparison with PRDM1α, and upregulation of PRDM1β might provide a survival advantage by competing with the remaining PRDM1α.

Discussion

Here we show that FOXO1 downregulation contributes to the extinction of the B-cell program in cHL and plays an important role in PRDM1α repression. To our knowledge, FOXO1 has never been reported to induce PRDM1 or to facilitate PC differentiation. Our finding apparently contradicts previously published observations. Given that FOXO1 induces BCL6, a PRDM1 antagonist and repressor of PC differentiation,51 it would be logical to assume that FOXO1 inhibits or delays PC differentiation. Indeed, it was reported that Foxo1 knockout enhances generation of PCs,52 and constitutively active Foxo1 decreases formation of antibody-secreting cells.53 On the other hand, FOXO3 levels substantially increase during PC differentiation.54 These discrepancies might be caused by the known differences in B-cell differentiation between human and mouse,55 or they may represent a cHL-specific phenomenon. It is possible that the effect of FOXO1 is strongly context dependent and requires other factors, such as NF-κB, IRF4, and STAT3. This would imply that FOXO1 specifically contributes to PRDM1α induction in a specific differentiation stage. This issue certainly requires further investigation.

When activating FOXO1 in cHL cell lines, in some cases we observed coinduction of the known antagonists PRDM1α and BCL6.56 This resembles the previously reported transitory dichotomous expression of PRDM1 and BCL6 in normal B cells committed to PC differentiation.57,58 It is conceivable that FOXO1 is critical for the initiation of both BCL6 and PRDM1 expression, whereas the decision for the expression of the preferred gene might depend on other factors.

In this study, we provide evidence for PRDM1α as a tumor suppressor in cHL. Its tumor suppressor function has already been shown in different lymphoid malignancies,59 including ABC-DLBCL.14,16 In contrast to ABC-DLBCL, mutations and chromosomal aberrations do not play a major role in cHL, a finding that is supported by a previous study of cHL cell lines.47 Additionally, our data demonstrate that promoter hypermethylation is also not a primary cause of PRDM1α downregulation.

So far, the only known mechanism that might contribute to PRDM1α repression in cHL cell lines was high expression of the micro-RNAs miR-9 and let-7a.47,60 These results highlight the importance of gene regulatory mechanisms for PRDM1α repression in cHL and identify a central role for FOXO1 in this context.

We also found that FOXO1 activation strongly downregulates MYC, which is essential for the survival of cHL.8 FOXO1 is known to repress MYC on transcriptional and posttranscriptional levels by upregulation of specific miRNAs.61,62 As PRDM1 is a repressor of MYC transcription, our data implicate a novel mechanism by which FOXO1 downregulates MYC. We further show that MYC represses PRDM1 in cHL. This is in line with a previous study showing that MYC represses PRDM1α in primary GC B cells and in Burkitt lymphoma cell lines.44 Therefore, MYC repression might contribute to FOXO1-mediated induction of PRDM1α. We propose that FOXO1, PRDM1α, and MYC constitute a negative feed-forward regulatory loop driven by FOXO1 (Figure 7). In the absence of FOXO1, the regulation might become imbalanced in favor of MYC, which might ultimately lead to a block of PC differentiation.

Model–FOXO1 repression in cHL contributes to a block of PC differentiation and is required for high MYC expression. In the absence of FOXO1, JAK/STAT, NF-κB, and IRF4 are not able to induce PRDM1α expression at high levels in cHL. Instead, MYC expression is high. Thus, downregulation of FOXO1 shifts PRDM1α–MYC balance toward MYC, thereby facilitating transformation or maintenance of the cHL oncogenic program. FOXO1 reactivation initiates a negative feed-forward loop resulting in high PRDM1α levels and MYC repression.

Model–FOXO1 repression in cHL contributes to a block of PC differentiation and is required for high MYC expression. In the absence of FOXO1, JAK/STAT, NF-κB, and IRF4 are not able to induce PRDM1α expression at high levels in cHL. Instead, MYC expression is high. Thus, downregulation of FOXO1 shifts PRDM1α–MYC balance toward MYC, thereby facilitating transformation or maintenance of the cHL oncogenic program. FOXO1 reactivation initiates a negative feed-forward loop resulting in high PRDM1α levels and MYC repression.

Our study supported the finding that PRDM1β is expressed in cHL.64 It is believed that this short form acts as a dominant negative inhibitor.41,63 In agreement with previous findings showing that PRDM1β retains only 50% of the ability to repress MYC,41 we demonstrate that PRDM1β has a reduced antiproliferative effect in cHL cell lines. We propose that PRDM1β expression provides an advantage for HRS cells by interfering with the function of residual PRDM1α.

Taken together, we show that FOXO1 repression contributes to a block of PC differentiation by downregulating PRDM1α. In addition, we identified PRDM1α as a tumor suppressor in cHL. In a broader view, it will be interesting to investigate whether FOXO1 inactivation contributes to PRDM1α repression and block of terminal differentiation in other B lymphoma entities with an ABC-like oncogenic program. Further, our results imply a role of FOXO transcription factors during normal PC differentiation. Future studies in this direction are warranted.

The microarray data reported in this article have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession number GSE29545).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Vasily Ogryzko of the Institut de Cancerologie Gustave Roussy, Villejuif, France, for donating the BirA-expressing vector. The authors also thank the Core Facility FACS of the Medical Faculty, University of Ulm, for sorting, Frank Leithäuser for critically reading the manuscript, and Petra Weihrich for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported in part by grants from Deutsche Krebshilfe eV (grant 110564) (T.W., A.U.) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant 81101788) (H.G.) (grant 81201867) (L.X.).

Authorship

Contribution: M.J.V., L.X., H.G., R.M.T., T.M., U.K., H.J.M., K.H., F.C.C., C.S., J.B.R., C.D.W., F.G., A.B.K., E.C., M.R., R.D.G., and A.U. performed research and analyzed data; and M.J.V., H.J.M., P.M., T.W., and A.U. designed research and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Thomas Wirth, Institute of Physiological Chemistry, University of Ulm, Albert-Einstein-Allee 11, 89081 Ulm, Germany; e-mail: thomas.wirth@uni-ulm.de; and Alexey Ushmorov, Institute of Physiological Chemistry, University of Ulm, Albert-Einstein-Allee 11, 89081 Ulm, Germany; e-mail: alexey.ushmorov@uni-ulm.de.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal