Abstract

Endothelial cell protein C receptor (EPCR) was first identified and isolated as a cellular receptor for protein C on endothelial cells. EPCR plays a crucial role in the protein C anticoagulant pathway by promoting protein C activation. In the last decade, EPCR has received wide attention after it was discovered to play a key role in mediating activated protein C (APC)-induced cytoprotective effects, including antiapoptotic, anti-inflammatory, and barrier stabilization. APC elicits cytoprotective signaling through activation of protease activated receptor-1 (PAR1). Understanding how EPCR-APC induces cytoprotective effects through activation of PAR1, whose activation by thrombin is known to induce a proinflammatory response, has become a major research focus in the field. Recent studies also discovered additional ligands for EPCR, which include factor VIIa, Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein, and a specific variant of the T-cell receptor. These observations open unsuspected new roles for EPCR in hemostasis, malaria pathogenesis, innate immunity, and cancer. Future research on these new discoveries will undoubtedly expand our understanding of the role of EPCR in normal physiology and disease, as well as provide novel insights into mechanisms for EPCR multifunctionality. Comprehensive understanding of EPCR may lead to development of novel therapeutic modalities in treating hemophilia, inflammation, cerebral malaria, and cancer.

Introduction

Endothelial cell protein C receptor (EPCR) was originally identified and cloned as a endothelial cell-specific transmembrane glycoprotein capable of binding to protein C and activated protein C (APC).1 EPCR plays a critical role in protein C activation by the thrombin-thrombomodulin (TM) complex.2 Recent studies established that EPCR plays a crucial role in supporting APC-mediated cytoprotective signaling. Studies performed in the last few years have shown that EPCR also binds other ligands, which paves unsuspected new roles for the receptor. In this review, we discuss the recent literature on EPCR, with a specific emphasis on discoveries of novel ligands for the EPCR and how they expand the role of EPCR in pathophysiology.

EPCR structure with bound ligands

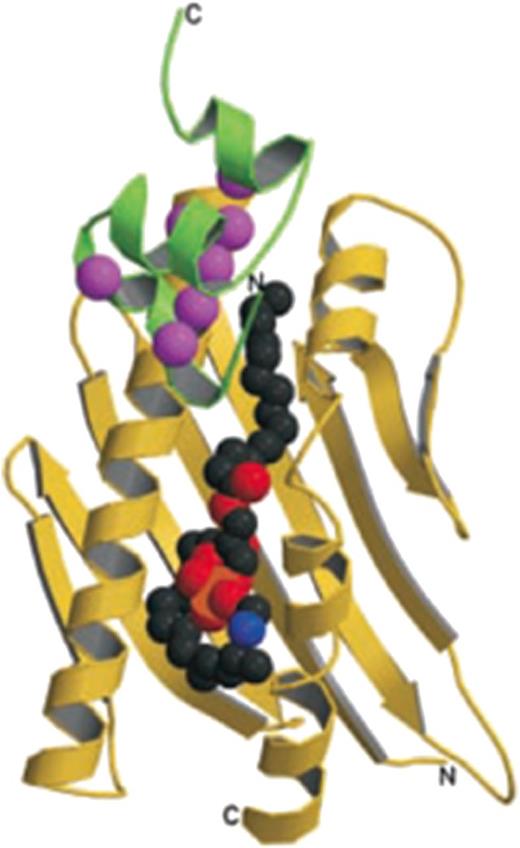

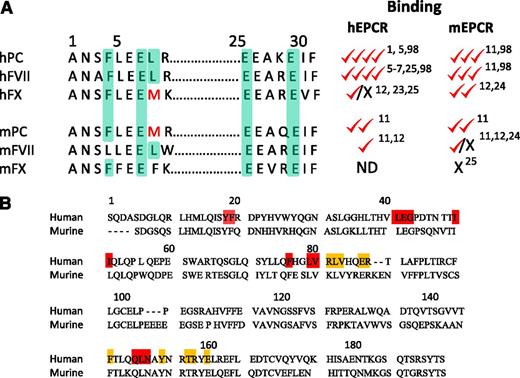

EPCR is a type 1 transmembrane protein that exhibits sequence and 3-dimensional structural homology with the major histocompatibility class 1/CD1 family of proteins, particularly CD1d1,3 (Figure 1). Similar to the CD1 family of proteins, EPCR has a tightly bound phospholipid in the antigen presenting groove, and the extraction of lipid resulted in the loss of protein C binding.3 Recent studies showed phosphatidylcholine as the major phospholipid bound to human EPCR, which could be exchanged with lysophosphatidylcholine and platelet activating factor, facilitated by the enzymatic action of secretory group V phospholipase A2.4 The placement of lysophosphatidylcholine and platelet activating factor in the hydrophobic groove impaired the ability of EPCR to bind protein C.4 The crystal structure of the complex of human EPCR bound to the human protein C Gla domain identified that Phe-4 and Leu-8 located in the conserved ω-loop of the protein C Gla domain contribute to the majority of the binding energy required to interact with EPCR. Another 3 residues of the protein C Gla domain that interact with EPCR are Gla-7, Gla-27, and Gla-29. All residues in protein C that were shown to interact with EPCR are fully conserved in human factor VII (FVII) but not in other human Gla domain proteins (Figure 2). Both FVII and FVIIa were shown to bind EPCR with a similar affinity as of protein C (∼40 nM).5-7 Interestingly, none of murine Gla domain proteins, including protein C, contain Phe-4 and Leu-8 simultaneously (Figure 2). Nonetheless, both in vivo and in vitro studies indicate that murine protein C binds murine EPCR.8-12 In contrast, murine FVII/FVIIa fails to bind murine EPCR in any significant manner.11,12 However, human FVIIa binds murine EPCR with a similar high affinity as it binds human EPCR.11

EPCR structure. The soluble EPCR molecule (yellow ribbon) with a portion of the protein C Gla domain (green ribbon), and a lipid molecule (the space filling balls in the center). In EPCR, 2 α-helices and an 8-strand β-sheet create a groove that is filled with the phospholipid. Binding of calcium ions (magenta spheres) to the protein C Gla domain exposes the N-terminal ω-loop to interact with EPCR (reproduced from Oganesyan et al., J Biol Chem. 2002;277:24851-24854).3

EPCR structure. The soluble EPCR molecule (yellow ribbon) with a portion of the protein C Gla domain (green ribbon), and a lipid molecule (the space filling balls in the center). In EPCR, 2 α-helices and an 8-strand β-sheet create a groove that is filled with the phospholipid. Binding of calcium ions (magenta spheres) to the protein C Gla domain exposes the N-terminal ω-loop to interact with EPCR (reproduced from Oganesyan et al., J Biol Chem. 2002;277:24851-24854).3

Amino acid homology and binding characteristics of human and murine ligands to EPCR. (A) The amino acid residues in human protein C (hPC) that are involved in binding to human EPCR and the corresponding residues in other proteins were highlighted (light green color). Ability of these proteins to bind either human or murine EPCR is shown relative to human protein C binding to human EPCR, which was assigned 4 checkmarks. The binding properties reported earlier,1,5-7,11,12,23-25,98 including Kd values, relative amounts of the ligand bound to a constant amount of EPCR, and in vivo displacement of the bound ligand by exogenously administered competing ligand, were used cumulatively in assigning the relative binding. X, no detectable or significant binding; ND, not determined. Both the zymogen and the corresponding active protease ligand interact with EPCR with similar affinities. (B) Amino acid homology of the extracellular region of human and murine EPCR. The 10 residues highlighted with orange boxes are those that, when mutated to alanine, resulted in the loss of APC binding to hEPCR.99 Residues highlighted in red were shown to be important for proper EPCR conformation. Therefore, when these residues are mutated to alanine, they result in the loss of APC binding and all mAb epitopes.99

Amino acid homology and binding characteristics of human and murine ligands to EPCR. (A) The amino acid residues in human protein C (hPC) that are involved in binding to human EPCR and the corresponding residues in other proteins were highlighted (light green color). Ability of these proteins to bind either human or murine EPCR is shown relative to human protein C binding to human EPCR, which was assigned 4 checkmarks. The binding properties reported earlier,1,5-7,11,12,23-25,98 including Kd values, relative amounts of the ligand bound to a constant amount of EPCR, and in vivo displacement of the bound ligand by exogenously administered competing ligand, were used cumulatively in assigning the relative binding. X, no detectable or significant binding; ND, not determined. Both the zymogen and the corresponding active protease ligand interact with EPCR with similar affinities. (B) Amino acid homology of the extracellular region of human and murine EPCR. The 10 residues highlighted with orange boxes are those that, when mutated to alanine, resulted in the loss of APC binding to hEPCR.99 Residues highlighted in red were shown to be important for proper EPCR conformation. Therefore, when these residues are mutated to alanine, they result in the loss of APC binding and all mAb epitopes.99

EPCR expression and localization

Originally EPCR expression was reported to be primarily limited to endothelium of the large blood vessels with exceptions in some organs, such as the liver sinusoidal endothelium and spleen.13 However, others have reported low level expression on microvascular endothelium.14 EPCR expression is also detected in many other cell types including monocytes, neutrophils, smooth muscle cells, keratinocytes, placental trophoblasts, cardiomyocytes, and neurons.15 EPCR expression is also found on hematopoietic, neuronal, and epithelial progenitor cells and breast cancer stem cells.16-19 A majority of EPCR on cells is localized on the cell surface in membrane microdomains that are positive for caveolin-1.20 A small fraction of EPCR is also localized intracellularly in the recycling compartment.20 Ligand binding to EPCR promotes endocytosis of EPCR.20 Endocytosis of EPCR carries the ligand along with it into the recycling compartment. EPCR-mediated endocytosis and recycling facilitate the transport of its cargo across the endothelial cell barrier and thus influence the catabolism and bioavailability of its ligands.20,21 EPCR endocytosis and the subsequent intracellular trafficking are regulated by specific Rab GTPases in a temporospatial-dependent manner.22

EPCR novel ligands

Factor X

It has been reported that both human factor X (hFX) and hFXa bind hEPCR.23,24 The presence of tissue factor (TF) could influence the association between FX/FXa and EPCR.24 Furthermore, EPCR is shown to induce efficient cleavage of protease activated receptor-1 (PAR1) and PAR2 by the TF-FVIIa-FXa complex.24 However, we and others failed to observe any noticeable binding of hFX to hEPCR.12,25 Human FX contains the same sequence as of murine protein C in the EPCR binding region (Phe4-Leu-Glu-Met8; Figure 2). It had been shown that hFX binds murine (m)EPCR, but with a much lower affinity than protein C.12,24 It is unlikely that mFX binds mEPCR, as Leu-8 is substituted by Phe rather than by Met. Failure of administration of a high concentration of human APC to increase plasma levels of FX in EPCR-overexpressing mice supports the above notion.25 Further studies are needed to determine whether FX or FXa acts as a true ligand for EPCR and the biological significance of the interaction between FX/FXa and EPCR.

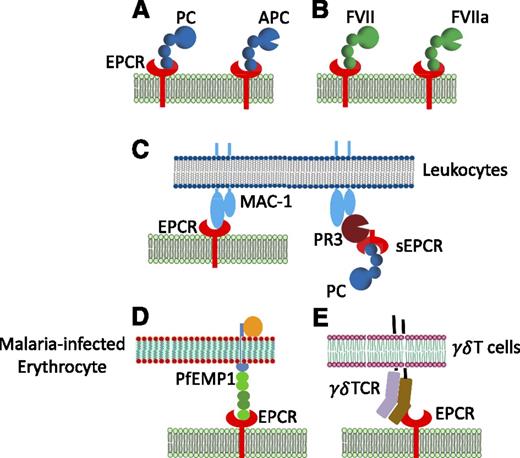

Proteinase-3/Mac-1

Soluble EPCR was found to bind activated neutrophils, and the binding protein was identified as proteinase-3 (PR3), an elastase-like protein released from activated neutrophils.26 Further studies revealed that β2 integrin Mac-1 contributes to sEPCR binding to the activated neutrophils as the PR3 forms a heteromeric complex with Mac-1 on neutrophils (Figure 3).26 Because APC failed to block sEPCR binding to activated neutrophils, it is believed that the EPCR binding site for PR3 was distinct from that of APC.26 Interestingly, PR3 not only acts as a ligand to EPCR but also cleaves EPCR at multiple sites, resulting in EPCR degradation.27 A recent study showed that EPCR also binds directly to Mac-1 on monocytes, and APC blocks this binding.28

Various ligands of EPCR. In addition to (A) acting as a cellular receptor for protein C (PC) and APC, (B) EPCR was shown to interact with factor VII (FVII) and factor VIIa (FVIIa), (C) Mac1 on leukocytes, either directly or indirectly through its binding to proteinase 3 (PR3), (D) P falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP1) expressed by P falciparum-infected erythrocyte, and (E) a variant of γδ T-cell receptor induced in response to stress elicited by infection or malignancy. PC/APC, FVII/FVIIa, Mac1, and PfEMP1 bind EPCR at the same or an overlapping site.

Various ligands of EPCR. In addition to (A) acting as a cellular receptor for protein C (PC) and APC, (B) EPCR was shown to interact with factor VII (FVII) and factor VIIa (FVIIa), (C) Mac1 on leukocytes, either directly or indirectly through its binding to proteinase 3 (PR3), (D) P falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP1) expressed by P falciparum-infected erythrocyte, and (E) a variant of γδ T-cell receptor induced in response to stress elicited by infection or malignancy. PC/APC, FVII/FVIIa, Mac1, and PfEMP1 bind EPCR at the same or an overlapping site.

γδ T-cell antigen receptor

T cells bearing γδ T-cell antigen receptor (TCR) play an important role in immune surveillance as they can target and kill infected and transformed cells. A subpopulation of γδ T cells (Vδ2−γδ T cells) recognizes cells infected with cytomegalovirus, and EPCR serves as a ligand for γδ TCR.29 γδ TCR binding to EPCR is dependent on the conformational integrity of EPCR but is independent of glycosylation and lipid binding status of EPCR. A distinct patch on the solvent-exposed surface of the β sheet of EPCR acts as the binding site to the γδ TCR.29 The ability of γδ TCR to bind EPCR raise the possibility that γδ T cells may use EPCR to survey the endothelium for signs of viral infection or to detect malignant cell type.29,30

Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein I

Sequestration of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes on the microvascular endothelium is a critical event in the pathogenesis of severe childhood malaria. This sequestration is mediated by specific interaction between members of the P falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP1) family and receptors on the endothelial cell lining. Severe malaria is associated with expression of specific PfEMP1 subtypes, such as DC8 and DC13. Recently, EPCR has been revealed as the potential binding partner to these specific subtypes on the endothelium.31 DC8 PfEMP1 binds EPCR with a high affinity (KD, ∼29 nM) and competes with protein C binding.31

Regulation of coagulation by EPCR

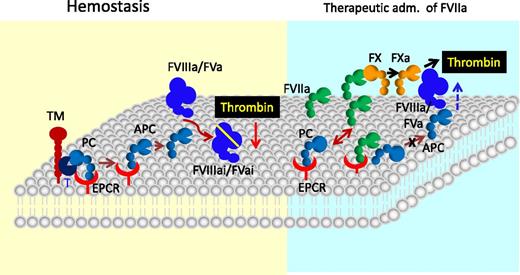

Activation of protein C is critical to the negative regulation of blood coagulation as APC inactivates FVIIIa and FVa, 2 key cofactors responsible for amplification of blood coagulation reactions that lead to thrombin generation (Figure 4). EPCR augments protein C activation by the thrombin-TM complex by lowering Km for the activation.2 The importance of EPCR in protein C activation in vivo was clearly established by the observation that anti-EPCR antibodies markedly reduced thrombin-induced APC generation in baboons.32 Marked impairment of APC generation in EPCR-deficient mice and enhanced APC generation in EPCR-overexpressing mice, and the inverse thrombin-antithrombin (TAT) complex levels in these mice further document the key role of EPCR in protein C activation and regulation of thrombin generation.9,33 The observation of normal protein C activation in EPCR+/− mice transplanted with bone marrow from EPCR−/− mice suggests that nonhematopoietic cell EPCR, presumably endothelial cell EPCR, is primarily responsible for the activation of protein C in vivo.34

The role of EPCR in blood coagulation. In hemostasis, EPCR promotes the activation of protein C (PC) bound to it by thrombin (T):TM complex. The APC then down-regulates thrombin generation by interacting with phospholipids on the membrane and inactivating cofactors factor VIIIa and factor Va. However, in specific therapeutical conditions, such as administration of a high concentration of rFVIIa to treat hemophilic patients with inhibitors or trauma patients, the EPCR anticoagulant function may be diminished as the exogenously administered FVIIa effectively competes with plasma protein C for binding to EPCR and thus displaces protein C from the EPCR, resulting in down-regulation of APC generation. Down-regulation of APC generation could lead to increased thrombin generation as FVa and FVIIIa are relieved from their inactivation by APC. This mechanism may be responsible partly to the hemostatic effect conferred by therapeutic administration of rFVIIa.

The role of EPCR in blood coagulation. In hemostasis, EPCR promotes the activation of protein C (PC) bound to it by thrombin (T):TM complex. The APC then down-regulates thrombin generation by interacting with phospholipids on the membrane and inactivating cofactors factor VIIIa and factor Va. However, in specific therapeutical conditions, such as administration of a high concentration of rFVIIa to treat hemophilic patients with inhibitors or trauma patients, the EPCR anticoagulant function may be diminished as the exogenously administered FVIIa effectively competes with plasma protein C for binding to EPCR and thus displaces protein C from the EPCR, resulting in down-regulation of APC generation. Down-regulation of APC generation could lead to increased thrombin generation as FVa and FVIIIa are relieved from their inactivation by APC. This mechanism may be responsible partly to the hemostatic effect conferred by therapeutic administration of rFVIIa.

Recent observations that EPCR also acts as a cellular receptor for FVII(a) raise the possibility that EPCR may regulate the blood coagulation independent of its role in protein C activation.15,35,36 Studies from us and others showed that FVIIa binding to EPCR had no effect on FVIIa activation of FX.5,24 However, it had been reported by others that EPCR attenuates TF-FVIIa activation of FX.7 EPCR was also shown to down-regulate the activation of FVII.37 At present, the physiological significance of EPCR interaction with FVII(a) in hemostasis is unclear. However, a recent study, using a mouse model system, has shown that the EPCR interaction with FVIIa contributes to the correction of hemostasis in the setting of pharmacologic rFVIIa administration in hemophilia.38 These data are consistent with our hypothesis that FVIIa binding to EPCR may induce procoagulant effect in specific therapeutic conditions, such as in treating hemophiliacs or trauma patients with high concentrations of FVIIa to restore hemostasis.5,35 Under these conditions, the plasma concentration of FVIIa could reach as much as the plasma concentration of protein C39 ; therefore, FVIIa could effectively compete with protein C for EPCR and thus result in downregulation of APC generation (Figure 4). Experiments conducted using an endothelial cell model system support this hypothesis.5,7 Infusion of high concentrations of human rFVIIa was shown to increase plasma levels of protein C in wild-type and EPCR-overexpressing mice, indicating that exogenously administered FVIIa could displace the bound protein C from EPCR.11

EPCR-mediated cell signaling and cytoprotection

Initial studies showing that blockade of protein C binding to EPCR exacerbated the response to sublethal doses of Escherichia coli in baboons,40 and the apparent success of APC in reducing mortality in patients with severe sepsis in a clinical trial41 indicated that EPCR-APC provides a cytoprotection. This concept received further support by studies of Joyce et al,42 who showed that APC directly modulated cell signaling and altered gene expression in 2 major pathways of inflammation and apoptosis. Riewald et al demonstrated that APC-induced cytoprotective signaling is mediated through APC activation of PAR1, and APC uses the EPCR as a coreceptor for the cleavage of PAR1.43 In subsequent studies, EPCR-APC activation of PAR1 in a variety of cell types was shown to exert multiple cytoprotective effects.44 They include beneficial alterations in gene expression profile, anti-inflammatory activities, antiapoptotic activity, and protection of endothelial barrier integrity (Figure 5). The literature on EPCR-APC–mediated cytoprotection and its mechanism and regulation were nicely summarized in recent reviews.15,36,44-47

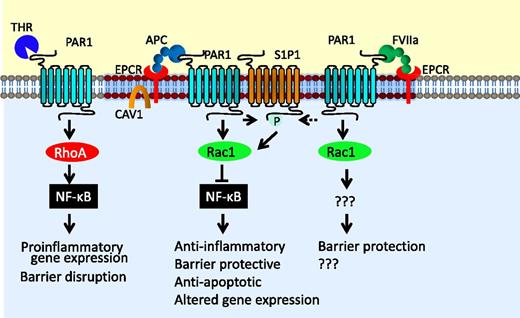

The cytoprotective signaling of EPCR-APC. EPCR-bound APC cleaves PAR1, and this PAR1 cleavage specifically activates Rac1 pathway, inhibits the activation of the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) pathway, and provides barrier protection. Cross-activation of the S1P1 by sphingosine kinase-1 stimulated by EPCR-APC activation of PAR1 may contribute to the EPCR-APC–mediated barrier protective effect and cell survival. FVIIa bound to EPCR can also cleave PAR1 and provide the barrier protective effect. However, mechanistic details involved in the FVIIa-EPCR–induced barrier protective effect are unknown. In contrast to EPCR-dependent PAR1 signaling, thrombin cleavage of PAR1 leads to RhoA activation and activation of nuclear factor-κB, leading to proinflammatory gene expression and barrier disruption. Various hypotheses were put forth on why EPCR-APC cleavage of PAR1 leads to cytoprotective signaling, whereas thrombin activation of PAR1 leads to proinflammatory response. These hypotheses have been discussed in the text.

The cytoprotective signaling of EPCR-APC. EPCR-bound APC cleaves PAR1, and this PAR1 cleavage specifically activates Rac1 pathway, inhibits the activation of the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) pathway, and provides barrier protection. Cross-activation of the S1P1 by sphingosine kinase-1 stimulated by EPCR-APC activation of PAR1 may contribute to the EPCR-APC–mediated barrier protective effect and cell survival. FVIIa bound to EPCR can also cleave PAR1 and provide the barrier protective effect. However, mechanistic details involved in the FVIIa-EPCR–induced barrier protective effect are unknown. In contrast to EPCR-dependent PAR1 signaling, thrombin cleavage of PAR1 leads to RhoA activation and activation of nuclear factor-κB, leading to proinflammatory gene expression and barrier disruption. Various hypotheses were put forth on why EPCR-APC cleavage of PAR1 leads to cytoprotective signaling, whereas thrombin activation of PAR1 leads to proinflammatory response. These hypotheses have been discussed in the text.

PAR1 was originally identified as a thrombin receptor.48 Thrombin cleaves PAR1 with 3 to 4 orders of magnitude higher catalytic efficiency than APC.49 In contrast to APC, thrombin cleavage of PAR1 was shown to induce proinflammatory responses and apoptosis and to enhance the barrier permeability in endothelial cells.50 Therefore, how EPCR-APC activation of the same receptor elicits exactly opposite response has become an enigma. Localization of EPCR with PAR1 in caveolae or caveolin-1–rich membrane microdomains and APC activation of PAR1 in these specific microdomains were thought to be responsible for EPCR-APC–mediated cytoprotection.51,52 It had been suggested that APC-selective signaling of PAR1 comes from APC-mediated PAR1-dependent transactivation of the sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P1) receptor and Tie2.53-55 The observation that thrombin activation of PAR1 does not result in S1P1 activation fits with this hypothesis.53 However, the above concepts alone are insufficient to explain why PAR1 activation of APC is fundamentally different from the activation by thrombin. Recent studies from several groups provided interesting clues on the biased signaling of PAR1 activated by EPCR-APC.

Rezaie and colleagues suggested that the binding of the Gla domain of APC to EPCR determines the type of PAR1 response rather than the protease type that cleaves the receptor.56 Their studies showed that when EPCR is occupied by its ligand, the cleavage of PAR1 by thrombin elicits protective signaling response in endothelial cells.56 EPCR localizes within the lipid rafts and interacts with caveolin-1.51 The ligand occupancy of EPCR leads to dissociation of EPCR from the caveolin-1, and this appears to change the PAR1-dependent signaling specificity of thrombin and APC from enhancing barrier permeability to a barrier protective response.47,56 They suggested that EPCR occupancy recruits PAR1 to a protective pathway by coupling the PAR1 to Gi/o protein instead of Gq and/or G12/13.47,56 Interestingly, EPCR occupancy by protein C was also shown to switch the signaling specificity of PAR2 activated by FXa from a barrier disruptive function to a barrier protective effect in endothelial cells.57

Recent studies of Soh and Trejo provided a different explanation for biased signaling of PAR1 by APC and thrombin.58 They showed that APC-activated PAR1 cytoprotective signaling is mediated by β-arrestin recruitment and activation of the dishevelled-2 (Dvl-2) scaffold in caveolar microdomains and not by G protein-dependent signaling as seen with thrombin activation of PAR1. The role of EPCR in recruitment of β-arrestin was unclear in these studies. It is possible that EPCR occupancy by its ligand, ie, APC, is responsible for APC-activated PAR1 recruiting β-arrestin. In a similar analogy, EPCR occupancy by its ligand may also couple thrombin-activated PAR1 signaling to β-arrestin/Dvl-2–mediated pathway.

Recent reports of noncanonical cleavage of PAR1 by APC have provided another important piece in the puzzle of understanding the differential signaling by thrombin and APC.59,60 These studies showed that APC cleaves PAR1 predominantly at Arg46 in the presence of EPCR, in contrast to thrombin cleavage of PAR1 at the canonical Arg41 site. A synthetic peptide comprising PAR1 residues 47 to 66 was shown to mimic APC-like protective signaling in endothelial cells. It had been suggested that cleavage of PAR1 at Arg46 by APC induces a subset of PAR1 conformations with functional consequences that differ from that induced by PAR1 cleaved at Arg41 site by thrombin.46,59 It is conceivable that PAR1 conformation conferred by APC cleavage at the noncanonical site initiates β-arrestin 2/Dvl-2–dependent signaling, leading to highly selective signaling outcomes and functional consequences for APC activation of PAR. Differences in specific conformations of PAR1 resulting from its cleavage by thrombin and APC may also explain why thrombin-cleaved PAR1 is rapidly internalized, whereas APC-activated PAR1 tends to remain on the cell surface.61 In a more recent study, Burnier and Mosnier showed that APC, in an EPCR-dependent manner, also activates PAR3 by cleaving at a noncanonical cleavage site (Arg41), and PAR3 tethered-ligand peptide beginning at amino acid 42 provides an endothelial barrier protective effect both in vitro and in vivo.62

Recent studies from our laboratory showed that EPCR-FVIIa also activates endogenous PAR1 on endothelial cells with the same efficiency as APC.63 Additional studies revealed that EPCR-FVIIa activation of PAR1 leads to the barrier protective effect both in vitro and in vivo.63,64 At present, it is unknown whether EPCR-FVIIa-PAR1–induced cytoprotection observed in our studies was mediated by the same mechanisms that had been proposed for EPCR-APC.

EPCR role in disease

Because EPCR is critical for the generation of APC and many of APC’s cytoprotective effects, the role of EPCR in a specific disease may be very similar to that of APC. In the following section, we limit our discussion to recent literature on novel functions of EPCR in a few key specific disease processes rather than providing a comprehensive review on cytoprotective actions of the protein C pathway, which have been reviewed in earlier articles.44,45,65

Inflammation

Increased evidence indicates that loss of EPCR expression or function contributes to inflammation in both severe and chronic conditions. Baboons challenged with a sublethal dose of E coli died more rapidly when administered with anti-EPCR antibody that blocks EPCR’s interaction with protein C/APC compared with baboons treated with a nonblocking EPCR antibody.40 The animals receiving the blocking mAb exhibited not only significantly elevated levels of the thrombin-antithrombin complex, increased consumption of fibrinogen, and microvascular thrombosis, but also elevated levels of interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-8 and an intense influx of neutrophils into the adrenal, renal, and hepatic microvasculature. Consistent with the above data that EPCR plays a crucial role in the host defense mechanism against an acute inflammatory challenge, EPCRLow mice exhibited reduced survival compared with wild-type mice following lipopolysaccharide (LPS) challenge.66,67 Studies with APC variants in wild-type and EPCRLow mice in an endotoxemia/sepsis model system showed that EPCR-mediated signaling is responsible for APC’s efficacy in reducing sepsis mortality.67 It had been shown that non–hematopoietic-derived EPCR is crucial for maintaining endogenous immune response to LPS challenge.34 However, Kerschen et al10 showed that EPCR on hematopoietic cells, ie, CD8+ dendritic cells, was required for exogenously administered APC to reduce the mortality of endotoxemia in mice. The importance of EPCR in providing protection against acute inflammation was further supported by the observation that EPCR-overexpressing mice exhibited reduced mortality compared with wild-type mice when challenged with LPS.9

EPCR may also play a role in controlling chronic inflammation. Individuals with active inflammatory bowel disease were found to exhibit reduced EPCR expression in their colonic mucosal microvasculature.68 Elaboration of inflammatory cytokines in inflammatory bowel disease may be responsible for diminished EPCR expression in the intestinal microvascular endothelium. Administration of APC was found to be therapeutically effective in ameliorating experimental colitis,68 indicating that impairment of protein C activation due to the loss of EPCR in the inflamed mucosal microvasculature may contribute to the disease.

The anti-inflammatory effects of EPCR come primarily from its effects on down-regulation of inflammatory mediators and vascular adhesion molecules, which reduces leukocyte adhesion and infiltration and thus limits damage to the underlying tissue. Most of these effects are mediated through EPCR’s role in APC generation and EPCR-APC–mediated cytoprotective signaling.44,45,65 However, EPCR may also affect inflammation independent of APC. The ability of soluble (s)EPCR to bind Mac-1 on neutrophils indirectly through its association with PR326 suggests that EPCR may interfere with neutrophil adhesion to activated endothelium.69 However, the ability of sEPCR and cell-associated EPCR to bind Mac1 directly28 suggests that the role of EPCR in leukocyte adhesion may vary and would be dependent on the ratio of sEPCR vs cell surface EPCR.

Recent literature provides compelling evidence that a breakdown in the endothelial barrier function plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of sepsis, and prevention of vascular leakage reduces mortality from sepsis.70 EPCR’s protective role in vivo in inflammation may come from its barrier protective effect. In vitro studies showed that EPCR confers a potent barrier protective effect through EPCR-APC–mediated activation of PAR1 that involves induction of sphingosine kinase-1 and up-regulation of S1P.53,54 In addition, EPCR-APC-PAR1–mediated cell signaling can also stabilize barrier function through the angiopoietin/Tie2 axis.55 EPCR occupancy by its ligand is shown to switch PAR1-dependent signaling specificity of thrombin from barrier permeability to barrier stabilization through up-regulation of the angiopoietin/Tie2 pathway.71 It is possible that EPCR-APC–induced barrier stabilization through the angiopoietin/Tie2 pathway may also involve S1P.

EPCR-FVIIa activation of PAR1 is also shown to provide a barrier protective effect, but the details of the mechanism are not fully known.63 Recent studies of von Drygalski et al72 demonstrated a protective role for EPCR in vivo against vascular leakage during inflammation. Their study revealed that EPCR-dependent vascular protection may be organ specific.72 Our recent studies of VEGF-induced permeability in the skin further established the importance of EPCR in providing a barrier protective effect.64 Our studies also showed that exogenous administration of FVIIa is as effective as APC in restoring the barrier integrity disrupted by vascular endothelial growth factor64 or LPS administration (L.V.M., C.T.E. and U.R.P., unpublished data, January 2012). The FVIIa-induced barrier protective effect in vivo is dependent on EPCR and involves PAR1 activation.64

Cancer

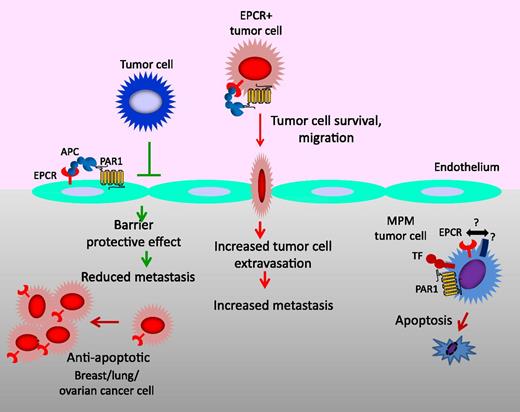

The role of EPCR in cancer is complex. The ability of EPCR to promote APC generation that attenuates thrombin formation should be advantageous in preventing tumor growth and metastasis. Similarly, EPCR-mediated vascular barrier protection may limit cancer metastasis by limiting cancer cell extravasation. However, EPCR-mediated cell signaling in a tumor cell may promote cancer cell migration, invasion, and angiogenesis and inhibit cancer cell apoptosis.73-76 Data from recent studies reflect these opposing effects of EPCR in cancer.

In murine B16-F10 metastasis models, transgenic EPCR-overexpressing mice exhibited a marked reduction in liver and lung metastasis compared with wild-type animals.77,78 A similar reduction in metastasis is also observed in wild-type mice when treated with APC.78 Endogenous APC is shown to limit cancer cell extravasation through S1P1-mediated vascular endothelial-cadherin–dependent vascular endothelial barrier enhancement.77 Endogenous APC also plays a role in immune-mediated cancer cell elimination from the circulation.79 In contrast to the above findings, EPCR appears to promote tumor metastasis in lung adenocarcinoma as EPCR silencing or blockade of its interaction with APC reduced infiltration of tumor cells in the target organ and resulted in impaired prometastatic activity.74 Conversely, EPCR overexpression in lung adenocarcinoma cells increased the metastatic activity in the target organs.74 It is possible that EPCR on the endothelium of host and EPCR on tumor cells may have opposing effects on cancer metastasis (Figure 6).

Multiple effects of EPCR on cancer. In the vasculature, the EPCR-APC–mediated signaling pathway on the endothelium provides an antimetastatic effect by inhibiting the extravasation of tumor cells through down-regulation of vascular adhesion molecules on the endothelium that are involved in tumor cell adhesion and by enhancing barrier integrity of the endothelium. EPCR on tumor cells may increase the metastatic potential as EPCR-APC signaling promotes tumor cell survival, migration, and invasion. In the tumor compartment, EPCR, in general, promotes tumor growth and burden through its survival benefits. However, in malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM), EPCR suppresses tumor growth by promoting tumor cell apoptosis and/or inhibiting tumor cell proliferation. At present, it is unclear whether specific receptor(s) present on MPM cells or the pleural microenvironment is responsible for the EPCR-mediated tumor cell apoptosis in MPM. TF, tissue factor; PAR1, protease activated receptor-1.

Multiple effects of EPCR on cancer. In the vasculature, the EPCR-APC–mediated signaling pathway on the endothelium provides an antimetastatic effect by inhibiting the extravasation of tumor cells through down-regulation of vascular adhesion molecules on the endothelium that are involved in tumor cell adhesion and by enhancing barrier integrity of the endothelium. EPCR on tumor cells may increase the metastatic potential as EPCR-APC signaling promotes tumor cell survival, migration, and invasion. In the tumor compartment, EPCR, in general, promotes tumor growth and burden through its survival benefits. However, in malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM), EPCR suppresses tumor growth by promoting tumor cell apoptosis and/or inhibiting tumor cell proliferation. At present, it is unclear whether specific receptor(s) present on MPM cells or the pleural microenvironment is responsible for the EPCR-mediated tumor cell apoptosis in MPM. TF, tissue factor; PAR1, protease activated receptor-1.

EPCR is expressed by highly aggressive basal-like breast cancer cell types and considered one of the critical markers for breast cancer stem cells.17,19 Recently, Schaffner et al80 showed that EPCR-expressing cells isolated from mammary fat pad-enhanced MDA-MB-231 mfp cells have stem cell-like properties. They also reported that EPCR-expressing cells, selected from expansion of an EPCR+ cancer stem cell-like population of MDA-MB-231 mfp cells, had markedly increased tumor cell-initiating activity compared with EPCR− cells. Administration of EPCR blocking antibodies reduced tumor initiation and growth of EPCR+ cells, indicating that ligands for EPCR present in the tumor microenvironment regulate these cancer stem cell-like populations.80 In agreement with these data, we found that EPCR overexpression in breast cancer cells increased the tumor cell growth potential, at least in the initial stage of tumor growth.81 Interestingly, in the later stage of tumor progression, the differences in tumor growth between tumors derived from EPCR+ or EPCRlow cells vanished. In fact, at the end of a 60-day experimental period, tumor volume in mice injected with EPCR+ cells was 30% lower than mice injected with EPCRlow cells.81 Analysis of tumor tissue sections revealed a significant reduction in macrophage infiltration and angiogenesis in tumors derived from EPCR-expressing tumor cells, which may be responsible for the reduction of the tumor growth of EPCR-expressing tumor cells at a later stage.

As discussed in an earlier section, EPCR-mediated cell signaling typically activates cell survival and antiapoptotic pathways.44 However, in specific cell types and/or in a specific in vivo microenvironment, EPCR-mediated cell signaling may actually activate cytotoxic apoptotic pathways. For example, we recently found that EPCR functions as a crucial negative regulator of cancer progression in malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) because the introduction of EPCR expression to aggressive MPM cells lacking EPCR completely attenuated their tumorigenicity, whereas the knockdown of EPCR expression in nonaggressive MPM cells expressing EPCR markedly increased their tumorigenicity.82 This study also revealed that EPCR in MPM cells promotes tumor cell apoptosis in vivo. These data are quite intriguing, and at present, the mechanism by which EPCR activates cytotoxic effect in MPM cells is unknown.

Recent studies raise the possibility that EPCR may influence cancer pathogenesis through modulation of innate immunity. γδ T cells are innate lymphocytes that recognize and kill a range of tumor cells.82,83 The recent observation that showed EPCR acts as a ligand to a subset of human γδ T cells29 raises the possibility that EPCR present on tumor cells could direct γδ T cells toward the tumor to facilitate tumor killing. In this context, expression of EPCR on tumor cells would make them more susceptible for anticancer immunity. If so, dysregulation of EPCR in tumorigenesis may influence tumor surveillance. A costimulatory ligand is required for EPCR-dependent activation of γδ T cells.29 This requirement may safeguard against γδ T cells reacting with EPCR-expressing cells under normal conditions.

The EPCR expression pattern in various human cancers also suggests that EPCR either could promote or limit cancer progression.84-88 Scheffer et al found that expression of EPCR in tumor cells is a rare event, and more EPCR+ tumors could be found in stage pT1 than in pT2.88 Analysis of EPCR expression in lung adenocarcinomas of a large group of patients showed a variable degree of EPCR expression in the lungs of these patients; high EPCR levels appeared to be associated with poor prognosis in stage 1 patients but not in patients with more advanced disease.74 Heng et al reported significantly higher levels of EPCR expression in lung carcinoma compared with para-carcinoma tissues, and EPCR expression was found to be correlated to tumor size and lymph node metastasis.85 In breast cancer, EPCR expression was found in in situ carcinoma within the luminal A subtype but not in invasive tumors.19 It had been suggested that sEPCR can be a biomarker of cancer progression.85,86

Malaria

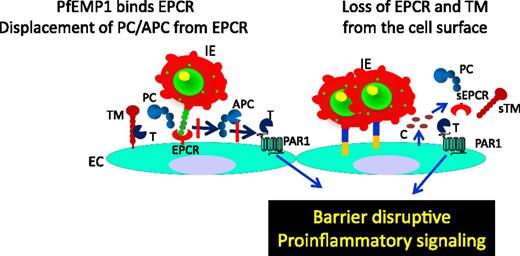

Sequestration of P falciparum-infected erythrocytes in the microvasculature involves the specific interaction of the PfEMP1 family of proteins on infected erythrocytes and receptors on the endothelial cell lining.89 Severe malaria is associated with the expression of specific subtypes of PfEMP1 containing domain cassettes (DCs)8 and 13.90 A recent observation of Turner et al31 that showed EPCR acts as a specific receptor for DC8 and DC13 PfEMP1 indicates that EPCR plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of severe malaria. The interaction between PfEPMP1 on infected erythrocytes and EPCR on the endothelium not only leads to sequestration of P falciparum-infected erythrocytes in host blood vessels but also impairs EPCR-mediated generation of the APC or EPCR-APC–mediated cytoprotective effect because PfEMP1 binds EPCR near or at the same region of APC and therefore prevents protein C and APC binding to EPCR31 (Figure 7). The finding that PfEMP1 binds to EPCR provides important clues for understanding severe malaria pathology and for the development of new malaria interventions.

Role of EPCR in malaria. In malaria, Plasmodium-infected erythrocytes (IEs) express PfEMP1 on the membrane. PfEMP1 binds EPCR in the same region as protein C (PC) and APC; therefore, IEs expressing PfEMP1 compete with PC and APC for EPCR. Such competition reduces PC and APC binding to EPCR and leads to down-regulation of PC activation by the thrombin (T):TM complex and loss of EPCR-APC–induced cytoprotective signaling. This results in increased barrier disruption and proinflammatory responses. Furthermore, binding of IEs to the endothelium, either through PfEMP1-EPCR interaction or other adhesive mechanisms, activates endothelial cells, and the activated endothelial cells release proinflammatory cytokines (C), which induce shedding of EPCR and TM from the cell surface. Loss of EPCR and TM from the cell surface impairs the ability of the endothelium to generate the APC and APC-induced cytoprotective effect. Down-regulation of APC also leads to increased thrombin generation and thrombin-induced proinflammatory reactions.

Role of EPCR in malaria. In malaria, Plasmodium-infected erythrocytes (IEs) express PfEMP1 on the membrane. PfEMP1 binds EPCR in the same region as protein C (PC) and APC; therefore, IEs expressing PfEMP1 compete with PC and APC for EPCR. Such competition reduces PC and APC binding to EPCR and leads to down-regulation of PC activation by the thrombin (T):TM complex and loss of EPCR-APC–induced cytoprotective signaling. This results in increased barrier disruption and proinflammatory responses. Furthermore, binding of IEs to the endothelium, either through PfEMP1-EPCR interaction or other adhesive mechanisms, activates endothelial cells, and the activated endothelial cells release proinflammatory cytokines (C), which induce shedding of EPCR and TM from the cell surface. Loss of EPCR and TM from the cell surface impairs the ability of the endothelium to generate the APC and APC-induced cytoprotective effect. Down-regulation of APC also leads to increased thrombin generation and thrombin-induced proinflammatory reactions.

Sequestration of P falciparum-infected erythrocytes in the cerebral microvasculature causes major health complications and has a very high morbidity and mortality rate, whereas sequestration of infected erythrocytes on other tissues has fewer or no consequences. A recent study by Moxon et al91 provides an explanation for why the brain is preferentially affected by the sequestration of infected erythrocytes. In a postmortem analysis of African children who died with cerebral malaria (CM), they found fibrin clots and loss of EPCR and TM expression in the microvasculature of the brain where infected erythrocytes were sequestrated. Higher levels of soluble EPCR and TM in the cerebrospinal fluid in children with CM over febrile control patients suggested that increased receptor shedding may be responsible for the reduction of EPCR and TM in the microvasculature. Overall, these data indicate that CM is associated with localized disturbance of coagulation, and probably inflammation, caused by a local loss of EPCR and TM following the sequestration of infected erythrocytes. Because of the already low constitutive expression of EPCR and TM in brain microvessels13,91 and the pleiotropic effects of EPCR and TM on coagulation and inflammation, any reduction in EPCR and TM in the brain microvasculature in CM may result in functional loss of EPCR and TM, shifting the thrombin-protein C axis toward a procoagulant, proinflammatory, and barrier destabilization state.

The studies by Turner et al31 and Moxon et al91 clearly demonstrate a critical role for EPCR in malaria and open new avenues for basic and translational research in the malaria research field. They also provide a rationale for the development of novel therapeutic strategies based on soluble EPCR and EPCR ligands (refer to the original articles and subsequent comment/review articles for further discussion on this92-94 ). The addition of soluble EPCR at levels between 15 and 300 ng/mL was shown to progressively inhibit the binding between DC8-expressing parasites and endothelial cells.31 Consistent with the hypothesis that elevated levels of soluble EPCR may protect from severe malaria, a recent study of genotyping of 707 Thai patients with P falciparum malaria showed that patients with the EPCR haplotype rs867186-G allele (serine to glycine substitution at position 219 of EPCR), which had been shown to be associated with higher levels of plasma-soluble EPCR, were protected from severe malaria.95

As described in an earlier section, EPCR is also shown to bind to a specific variant of the T-cell receptor present on γδ T cells.29 It had been suggested that γδ T cells are involved in the initial stage of P falciparum infection.96,97 It will be interesting to investigate in the future whether EPCR targeting of γδ T cells also plays a role in the pathogenesis of severe malaria.

Concluding remarks

Recent studies discovered many new ligands and novel functions for EPCR. The discovery that FVIIa binds EPCR with the same affinity as of protein C/APC and is capable of providing barrier protective effect in an EPCR-dependent manner opens novel therapeutic options for FVIIa or modified FVIIa from restoring hemostasis in hemophiliacs to preventing tissue edema and damage in specific disease conditions. The role of EPCR in cancer appears to be complex. New data identifying EPCR as a stress ligand for a subset of γδ T cells may help in the design of new immunotherapies for cancer. Recent observations on the important role of EPCR in malaria pathogenesis could lead to exciting research in this field and may lead to novel therapeutic approaches in treating severe malaria.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants HL107483 (L.V.M.R.) and UM1 HL120877 (C.T.E.).

Authorship

Contribution: All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: L. Vijaya Mohan Rao, Department of Cellular and Molecular Biology, The University of Texas Health Science Center, Tyler, TX 75708-3154; e-mail: vijay.rao@uthct.edu.