Key Points

The Kd for the association of FXIII subunits is in the range of 10−10 M, and in plasma approximately 1% of FXIII-A2 exists in free form.

The binding site for FXIII-A is located within the 2 N-terminal sushi domains of FXIII-B.

Coagulation factor XIII (FXIII) is a heterotetramer consisting of 2 catalytic A subunits (FXIII-A2) and 2 protective/inhibitory B subunits (FXIII-B2). FXIII-B, a mosaic protein consisting of 10 sushi domains, significantly prolongs the lifespan of catalytic subunits in the circulation and prevents their slow progressive activation in plasmatic conditions. In this study, the biochemistry of the interaction between the 2 FXIII subunits was investigated. Using a surface plasmon resonance technique and an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay–type binding assay, the equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd) for the interaction was established in the range of 10−10 M. Based on the measured Kd, it was calculated that in plasma approximately 1% of FXIII-A2 should be in free form. This value was confirmed experimentally by measuring FXIII-A2 in plasma samples immunodepleted of FXIII-A2B2. Free plasma FXIII-A2 is functionally active, and when activated by thrombin and Ca2+, it can cross-link fibrin. In cerebrospinal fluid and tears with much lower FXIII subunit concentrations, >80% of FXIII-A2 existed in free form. A monoclonal anti-FXIII-B antibody that prevented the interaction between the 2 subunits reacted with the recombinant combined first and second sushi domains of FXIII-B, and its epitope was localized to the peptide spanning positions 96 to 103 in the second sushi domain.

Introduction

Blood coagulation factor XIII (FXIII) is a protransglutaminase that is converted into an active form (FXIIIa) by the concerted action of thrombin and Ca2+ in the final phase of the clotting cascade. Transglutaminases crosslink peptide chains by ε(γ-glutamyl)lysyl bonds, and the main task of FXIIIa is to crosslink fibrin α and γ chains and covalently attach α2-plasmin inhibitor to fibrin. This mechanism is essential for maintaining hemostasis; it protects newly formed fibrin from the shear stress of circulating blood and from degradation by the fibrinolytic machinery. Plasma FXIII (pFXIII) is a heterotetramer (FXIII-A2B2) consisting of 2 potentially active A subunits (FXIII-A2) and 2 carrier/inhibitory B subunits (FXIII-B2). FXIII-A2 consists of 4 structural domains (a β-sandwich domain, a catalytic core domain, and 2 β-barrel domains) and an N-terminal activation peptide. FXIII-B is a mosaic protein consisting of 10 so-called sushi domains, each held together by a pair of disulfide bonds. It is a glycoprotein containing approximately 8.5% carbohydrate. FXIII-A2 also exists in the cytoplasm of certain cells, particularly platelets and monocytes/macrophages.1,2

FXIII-A is synthesized by cells of bone marrow origin, whereas FXIII-B is produced by hepatocytes.3,,,-7 The 2 subunits form a complex in the plasma; FXIII-B is in excess, and approximately 50% of it exists in free form,8 very likely as dimer.9,10 Complex formation between the 2 subunits is essential for maintaining normal hemostasis. The main role of FXIII-B is to prolong the lifespan of FXIII-A in the circulation.11 In FXIII-B–deficient patients, the FXIII-A2 concentration in the plasma is significantly decreased, and due to the low level of FXIII-A2, these patients present moderate bleeding diathesis.11,-13 This role of FXIII-B may be related to the prevention of a slow progressive activation of FXIII-A2, which may occur in plasmatic conditions in the absence of FXIII-B.14 Considering the importance of complex formation between the 2 FXIII subunits, it is surprising that the biochemistry of their interactions is only superficially explored. The epitopes involved in the interaction of the 2 subunits have not been specified. Although it is generally accepted that FXIII-A in the circulation is “fully” complexed, this has not been proven experimentally. So far, 2 values (4 × 10−7 M and 8 × 10−8 M) have been reported for the apparent equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd).15,16 However, these values were determined in enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)-type binding assays using a relatively high (>10−8 M) FXIII-B subunit concentration as receptor. If total receptor concentrations [Rt] > > Kd, then the binding constant could be significantly overestimated.17 Indeed, using the above 2 binding constants and the mean plasma concentrations of FXIII-A and FXIII-B subunits, 87% or 55% of pFXIII-A2 should be in free form, which is evidently not the case. Most recently, the administration of recombinant FXIII-A2 (rFXIII-A2) has been introduced as substitution therapy in FXIII-A deficiency.18 The fact that the long-term survival of rFXIII-A2 in the circulation depends on its complex formation with the available free FXIII-B2 underlines the importance of exploring the mechanism of FXIII-A2B2 complex formation.

In the present study, several aspects of the interaction between the FXIII subunits was investigated. We determined the Kd for the interaction and calculated and experimentally determined the concentration of free FXIII-A2 in the plasma and other body fluids (cerebrospinal fluid [CSF] and tears). It was tested if free FXIII-A present in the plasma was functional. Finally, an anti-FXIII-B monoclonal antibody that prevented complex formation was produced and its epitope on FXIII-B was determined.

Methods

Materials

Human thrombin, hirudin, 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate, bovine serum albumin (BSA) fraction V, horseradish peroxidase (HRP) type VI, biotinamido-hexanoic acid hydrazide, goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Fc specific), and trypsin (proteomics grade) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Bis(sulfosuccinimidyl)suberate was a product of Pierce (Rockford, IL). Batroxobin moojeni was purchased from Pentapharm (Basel, Switzerland). Sheep anti-human FXIII-A and rabbit anti-human FXIII-B polyclonal antibodies were obtained from Affinity Biologicals (Ancaster, Canada) and Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA), respectively. Vectastain ABC reagent was from Vector (Burlingame, CA). HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG was purchased from Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories (Westgrove, PA). Streptavidin-coated microplates were from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Vantaa, Finland). Monoclonal anti-FXIII-A and anti-FXIII-B antibodies were produced in BALB/c mice (see in details in the supplemental Methods available on the Blood Web site).19,20 IgG was separated from ascites fluid by affinity chromatography on a protein G Sepharose column (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden). For the binding assay, anti-FXIII-B IgG was biotinylated at the carbohydrate moiety using biotinamido-hexanoic acid hydrazide reagent.21 CNBr-activated Sepharose 4B gel and CM5 sensor chips were from GE Healthcare.

FXIII preparations and FXIII antigen determinations

Highly purified human pFXIII22 and pFXIII-B223,24 were prepared from pooled human plasma. Cellular FXIII was prepared from human placenta,14 and rFXIII-A2 was a kind gift from Dr Eva H.N. Olsen (Novo Nordisk, Måløv, Denmark). Recombinant FXIII-B2 (rFXIII-B2) produced in insect cells was from Zedira (Darmstadt, Germany). FXIII-A2B2 and FXIII-A2 antigen concentrations were determined as described earlier.19,20

Surface plasmon resonance investigations

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) investigations were performed on Biacore X instrument (GE Healthcare). A total of 100 μg/mL pFXIII-B2 or rFXIII-B2 was immobilized to flow cell 2 of a CM5 sensor chip according to the amine coupling protocol. BSA was used to cover control flow cell 1. Various concentrations of cellular (placenta) FXIII-A2 (cFXIII-A2) or rFXIII-A2 in 10 mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid buffer (pH 7.4) containing 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM EDTA, and 0.005% volume to volume ratio (v/v) surfactant were used as analyte. The flow rate through the cells was 10 μL/minute. The solution used for regeneration contained 50 U/mL thrombin, 250 mM CaCl2, 10 mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid buffer, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.005% v/v surfactant (pH 7.4). In this setup, after cleaving off the activation peptide by thrombin, the bound FXIII-A2 dissociates from FXIII-B2 linked to the sensor chip. The association rate constant (ka), dissociation rate constant (kd), and equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd) were calculated using Biaevaluation software (GE Healthcare).

ELISA-type binding assay

Various concentrations of cFXIII-A2 or rFXIII-A2 were incubated with 0.25 nM FXIII-B2 for 1 hour at 23°C. In the meantime, 100 μL biotinylated monoclonal anti-FXIII-B antibody (1 μg/mL) was added to the wells of a streptavidin-coated microplate. After a 30-minute incubation, the nonbound biotinylated antibody was removed by washing. Then, 100 μL of the incubation mixture containing the formed complex was transferred to the wells and incubated for 1 hour. After extensive washing, the amount of formed complex was determined by using HRP-labeled anti-FXIII-A antibody and TMB substrate. The concentration of formed complex was determined by comparison with a standard curve of FXIII-A2B2. The Kd was calculated using GraphPad (San Diego, CA) Prism Software (version 5.0).

Calculation and measurement of free FXIII-A in body fluids

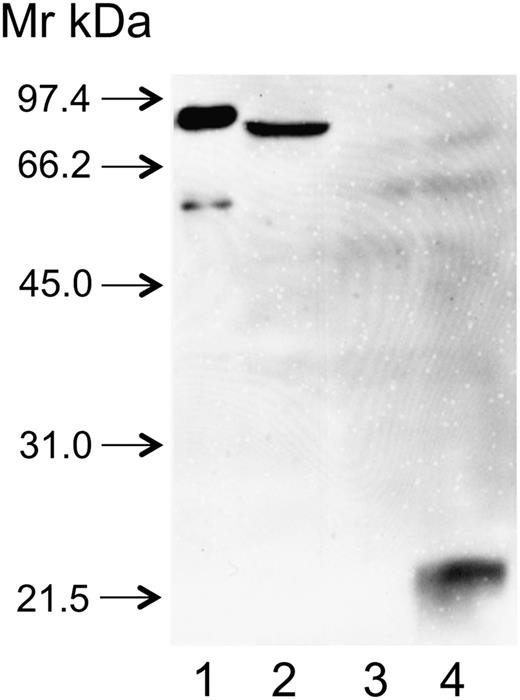

The following formula17 was used for the calculations:

where [R] is the receptor concentration [total FXIII-B2], [L] is the ligand concentration [total FXIII-A2], and [RL] is the concentration of the complex [FXIII-A2B2]. For plasma, [total FXIII-B2] and [total FXIII-A2] represent the mean of total FXIII-B2 and total FXIII-A220 concentrations determined in the plasma of 35 healthy volunteers. Mean and median concentrations reported earlier were used for the calculation concerning CSF and tears, respectively.25,26 Kd used in the formula was the mean of Kd values determined by SPR and the ELISA-type binding assay (4.17 × 10−10 M).

The measurement of free FXIII-A2 concentration in the plasma was performed on samples immunodepleted of FXIII-A2 present in complex. Citrated plasma samples from 11 healthy volunteers were depleted of FXIII-A2B2 and free FXIII-B by immunoabsorption using monoclonal anti-FXIII-B(1) antibody covalently coupled to Sepharose 4B. The complete removal of complexed FXIII-A2 was verified by the absence of FXIII-A2B2 in immunodepleted plasma samples. In the case of CSF and tears, the difference between the measured total molar concentrations of FXIII-A2 and FXIII-A2 in complex was considered the free FXIII-A2 concentration.

Characterization of anti-FXIII-B monoclonal antibodies

Based on preliminary screening experiments, 2 monoclonal anti-FXIII-B antibodies, anti-FXIII-B(1) and anti-FXIII-B(2), were selected for further studies. First, they were used for immunoprecipitation of FXIII-B2 from normal human plasma. The anti-FXIII-B antibodies were coupled to CNBr-activated Sepharose 4B gel (1.2 mg antibody/1 mL gel). A total of 1 mL normal human plasma was added to 100 μL antibody-coated beads and incubated for 2 hours at 23°C. After discarding the plasma, the beads were washed extensively with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.2). The immunoprecipitate was eluted by nonreducing sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) sample buffer at 95°C for 5 min. After centrifugation, the supernatants were reduced by 0.7 M 2-mercaptoethanol. The samples then were subjected to SDS-PAGE and analyzed by western blotting. The blots were incubated with sheep polyclonal anti-FXIII-A IgG or rabbit polyclonal anti-FXIII-B antibodies. The immune reaction was developed by biotinylated anti-sheep IgG and avidin-biotinylated peroxidase complex (Vectastain ABC kit) or by HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG. The reaction was visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence detection (ECL Prime Reagent; GE Healthcare).

Effect of anti-FXIII-B antibodies on the interaction of FXIII subunits

To test if anti-FXIII-B(2) monoclonal antibody inhibits the complex formation, we set up a modified ELISA that included the following steps: (1) binding of biotinylated monoclonal anti-FXIII-B(1) antibody (1 μg/mL in PBS dilution buffer containing 0.5% BSA and 0.5 M NaCl) to the wells of a streptavidin-coated microplate, (2) binding of FXIII-B2 (100 ng/mL in dilution buffer) to the immobilized antibody, (3) the addition of various concentrations of anti-FXIII-B(2) antibody or buffer to the wells, (4) the complex formation of surface-linked FXIII-B2 with FXIII-A2 (100 ng/mL in dilution buffer), and (5) measurement of the formed FXIII-A2B2 complex by HRP-labeled anti-FXIII-A antibody. Each incubation step was carried out at 23°C for 60 minutes, and it was followed by extensive washing with 0.05% Tween 20 in PBS. The amount of bound HRP-conjugated antibody was determined by TMB substrate at 450 nm.

Fibrin crosslinking by free FXIII-A2 remaining in the plasma after the removal of FXIII-A2B2 complex

The free FXIII-A2 that remained in the plasma after immunodepletion was investigated for fibrin crosslinking activity. Plasma samples were clotted by 2 U/mL human thrombin and 10 mM CaCl2 in the absence and presence of 2 mM iodoacetamide at 37°C for 60 minutes. After extensive washing with saline, the recovered clots were solubilized in reducing SDS-PAGE sample buffer and the dissolved clots were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. In certain experiments, thrombin was replaced by batroxobin (11 U/mL), a thrombin-like snake venom protease that clots fibrinogen by releasing fibrinopeptide A from the Aα chain of fibrinogen but does not activate FXIII-A2. In this case, the activation of FXIII by thrombin generated in the plasma in the presence of Ca2+ was inhibited by 10 U/mL hirudin.

Production of recombinant FXIII-B and its 1+2 sushi domains

FXIII-B and its 2 combined N-terminal sushi domains (SD1+2) were transiently expressed in Spodoptera frugiperda Sf9 insect cells using the InsectDirect kit from Novagen- EMD4Biosciences (Darmstadt, Germany).27 Briefly, F13B ORF (ImaGenes, Berlin, Germany; accession number BC148333) including the region coding for the signal peptide was amplified by PCR until the end of FXIII-B molecule or SD1+2. All primers included the extensions required by the ligation-independent cloning method, and reverse primers also included a stop codon (depicted in italics). The following primers were used: forward primer, 5′-CAG-GGA-CCC-GGT-ATG-AGG-TTG-AAA-AAC-CTG-AC-3′; reverse primer for FXIII-B, 5′-GG-CAC-CAG-AGC-GTT-TTA-TGT-TCT-TAA-GGG-TTC-TTG-AT-3′; reverse primer for SD1+2, 5′-GG-CAC-CAG-AGC-GTT-CTA-TGT-TTC-ATG-TTC-TTT-CC-3′. The PCR products were cloned into the insect cell expression vector pIEX/BAC-3 containing an AcNPV-derived hr5 enhancer and an IE1 promoter and an N-terminal 6×His tag. NovaBlue GigaSingle-competent cells (EMD4Biosciences) were transformed with this construct and the integrity of the insert of purified plasmid was verified by DNA sequencing. Sf9 insect cells were transfected using polyethylenimine (linear, Mr 25,000 Da)28 in a 1:4 plasmid-to-polyethylenimine ratio. Subsequently, a 1 × 107/mL suspension cell culture in BacVector serum free medium (Novagen) was grown for 48 hours at 28°C. The supernatant was concentrated and analyzed by western blotting using anti-FXIII-B(2) antibody. The immune reaction was developed by biotinylated anti-mouse IgG followed by avidin-biotinylated peroxidase complex (Vectastain ABC kit) and visualized by chemiluminescence detection.

Epitope mapping by mass spectrometry

Epitope mapping was performed by the method of Hager-Braun and Tomer in compact reaction columns (USB Corporation, Cleveland, OH).29 Polyclonal goat anti-mouse Fc-specific IgG was bound to CNBr-Sepharose beads, and then the monoclonal anti-human FXIII-B antibodies were covalently crosslinked to the immobilized anti-mouse IgG by bis(sulfosuccinimidyl)suberate. A total of 20 μL of washed and drained beads were incubated with 100 μL 10 μg/mL FXIII-B in PBS or with PBS alone at room temperature for 1 hour. After washing with 3 × 400 μL 0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.5), 50 μL 1 ng/mL trypsin in 0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.5) was added to the beads and incubated for 16 hours at 37°C. The supernatant was discarded and the beads were washed with 3 × 400 μL PBS and 3 × 400 μL 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate (pH 8.0). Approximately 1 μL of washed beads was mixed with 1 μL of saturated α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid in ethanol/water/formic acid (45/45/10 v/v/v) on a matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization target. The air-dried mixture was analyzed by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry on a Voyager DE STR instrument (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) in positive reflectron mode.

Results

Equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd) and kinetic parameters for the FXIII subunit interaction

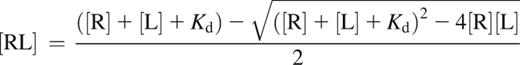

The Kd for the interaction of FXIII-A2 and FXIII-B2 was determined by SPR and an ELISA-type binding assay. The representative SPR sensorgrams (Figure 1A) and the binding curve (Figure 1B) demonstrate the binding of rFXIII-A2 to plasma-derived FXIII-B2. As demonstrated in Figure 1A, the fitting curves nicely followed the sensorgrams. The same experiments were also carried out with cFXIII-A2 prepared from human placenta. The Kd values obtained by both techniques were similar, in the range of 10−10, indicating tight binding (Table 1). The dissociation rate constants, approximately 2 × 10−4 s−1, suggest slow dissociation. As expected, there was hardly any difference between results with rFXIII-A2 and cFXIII-A2. The binding of rFXIII-A2 to rFXIII-B2 was also tested by SPR. rFXIII-B2 was produced in insect cells, in which the pattern of N-glycosylation is different from mammalian cells.30,31 The difference in N-glycan residues on FXIII-B2 resulting in a protein with a lower molecular mass did not influence significantly its interaction with FXIII-A2 (Table 1).

The binding of various concentrations of recombinant FXIII-A2to FXIII-B2. (A) FXIII-B prepared from plasma was fixed to a CM5 chip and the binding of FXIII-A2 was followed by the measurement of SPR. Each sensorgram corresponds to the rFXIII-A2 concentration indicated in the figure. The data were fit to a simple 1:1 interaction model using the global data analysis option available within Biaevaluation software. (B) The binding of rFXIII-A2 to plasma-derived FXIII-B2 was detected in an ELISA-type binding assay; the binding curve represents the means of 3 separate experiments not deviating by more than 10%. FXIII-A2B2/FXIII-B2(t): the molar concentration of measured formed FXIII-A2B2 was divided by molar concentration of total added FXIII-B2.

The binding of various concentrations of recombinant FXIII-A2to FXIII-B2. (A) FXIII-B prepared from plasma was fixed to a CM5 chip and the binding of FXIII-A2 was followed by the measurement of SPR. Each sensorgram corresponds to the rFXIII-A2 concentration indicated in the figure. The data were fit to a simple 1:1 interaction model using the global data analysis option available within Biaevaluation software. (B) The binding of rFXIII-A2 to plasma-derived FXIII-B2 was detected in an ELISA-type binding assay; the binding curve represents the means of 3 separate experiments not deviating by more than 10%. FXIII-A2B2/FXIII-B2(t): the molar concentration of measured formed FXIII-A2B2 was divided by molar concentration of total added FXIII-B2.

Kinetic parameters of FXIII-A2B2 complex formation

| . | n . | ka ± SE (1/Ms × 105) . | kd ± SE (1/s × 10−4) . | Kd ± SE (M × 10−10) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPR assay | ||||

| cFXIII-A2 + FXIII-B2 | 7 | 6.35 ± 0.80 | 2.62 ± 0.30 | 5.17 ± 1.44 |

| rFXIIII-A2 + FXIII-B2 | 4 | 5.76 ± 0.79 | 1.69 ± 0.08 | 3.14 ± 0.55 |

| rFXIII-A2 + rFXIII-B2 | 3 | 1.38 ± 0.30 | 0.76 ± 0.26 | 6.26 ± 2.76 |

| ELISA-type assay | ||||

| cFXIII-A2 + FXIII-B2 | 4 | — | — | 2.93 ± 0.68 |

| rFXIIII-A2 + FXIII-B2 | 3 | — | — | 5.43 ± 0.95 |

| . | n . | ka ± SE (1/Ms × 105) . | kd ± SE (1/s × 10−4) . | Kd ± SE (M × 10−10) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPR assay | ||||

| cFXIII-A2 + FXIII-B2 | 7 | 6.35 ± 0.80 | 2.62 ± 0.30 | 5.17 ± 1.44 |

| rFXIIII-A2 + FXIII-B2 | 4 | 5.76 ± 0.79 | 1.69 ± 0.08 | 3.14 ± 0.55 |

| rFXIII-A2 + rFXIII-B2 | 3 | 1.38 ± 0.30 | 0.76 ± 0.26 | 6.26 ± 2.76 |

| ELISA-type assay | ||||

| cFXIII-A2 + FXIII-B2 | 4 | — | — | 2.93 ± 0.68 |

| rFXIIII-A2 + FXIII-B2 | 3 | — | — | 5.43 ± 0.95 |

Results are expressed as mean ± standard error (SE).

rFXIII-B2, recombinant FXIII-B2.

Free FXIII-A2 in the plasma and other body fluids

Using the mean of Kd values measured by the 2 techniques and the mean total FXIII-A2 and FXIII-B2 concentration, the amount of complexed FXIII-A2 and free FXIII-A2 in the plasma was calculated (Table 2). According to the calculation, approximately 1% of the total FXIII-A2 should exist in free form, not associated with FXIII-B2. This surprising finding was tested experimentally. Eleven human plasma samples were fully depleted of FXIII-A2B2 and also of free FXIII-B2 by immunoabsorption using a monoclonal antibody, anti-FXIII-B(1), that equally reacted with both the free and complexed forms of FXIII-B2. The complete removal of FXIII-A2B2 was proven by a highly sensitive ELISA, the detection limit of which is 0.003 nM, which corresponds to 0.004% of average pFXIII-A2B2 concentration.19 In the immunodepleted plasma samples, 1.06 ± 0.49 nM free FXIII-A2 was measured; ie, 1.38% ± 0.55% of pFXIII-A2 existed in free form (Table 2).

Comparison of calculated and measured free FXIII-A2 in plasma and in other body fluids

| . | Mean/median total FXIII-B2 . | Mean/median total FXIII-A2 . | FXIII-A2 in complex calculated . | Free FXIII-A2 calculated . | % free FXIII-A2 calculated . | % free FXIII-A2 measured . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma | 113.1 nM | 69.9 nM | 69.2 nM | 0.7 nM | 1.0 | 1.38 ± 0.55 |

| CSF* | 113.0 pM | 80.4 pM | 3.37 pM | 12.9 pM | 81.0 | 95.8 |

| Tears* | 45.1 pM | 12.8 pM | 2.00 pM | 24.7 pM | 89.5 | 83.7 |

| . | Mean/median total FXIII-B2 . | Mean/median total FXIII-A2 . | FXIII-A2 in complex calculated . | Free FXIII-A2 calculated . | % free FXIII-A2 calculated . | % free FXIII-A2 measured . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma | 113.1 nM | 69.9 nM | 69.2 nM | 0.7 nM | 1.0 | 1.38 ± 0.55 |

| CSF* | 113.0 pM | 80.4 pM | 3.37 pM | 12.9 pM | 81.0 | 95.8 |

| Tears* | 45.1 pM | 12.8 pM | 2.00 pM | 24.7 pM | 89.5 | 83.7 |

Measured plasma free FXIII-A2 concentration was expressed as percentage of total FXIII-A2 concentration. The results represent the mean ± SD of values measured in 11 individual samples.

To test the validity of the established Kd, calculated and measured free FXIII-A2 were also compared in CSF and tears, in which FXIII subunit concentrations were at least 3 magnitudes lower than in the plasma. In such conditions, one would expect a much higher proportion of free FXIII-A2. Indeed, both the calculated and measured values were above 80%, and they showed fair agreement.

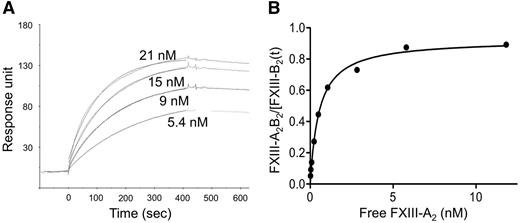

Free FXIII-A2 in the plasma is functionally intact

To answer the question of whether free FXIII-A2 present in the plasma is functionally intact, plasma immunodepleted of FXIII-A2B2 was treated by thrombin and Ca2+ and the formed clot was analyzed for fibrin crosslinking (Figure 2). Fibrin formed in nondepleted plasma showed complete dimerization of its γ chains and the formation of highly crosslinked α-chain polymers (αp). Fibrin chain crosslinking was prevented by the FXIIIa inhibitor iodoacetamide. In the immunodepleted plasma, the transglutaminase-dependent formation of γ-chain dimers was well detectable, demonstrating that free pFXIII-A2 can be transformed into an active transglutaminase. As opposed to nondepleted plasma, no αp was detected on the top of concentrating gel. This is not surprising; γ-chain dimerization is a highly sensitive indicator of FXIIIa activity, whereas α-chain polymerization requires much higher FXIIIa concentration and is a much slower process than γ-chain crosslinking.32,33 The fibrin crosslinking pattern in immunodepleted plasma corresponds well to the finding that only approximately 1% of pFXIIIFXIII-A2 is in free form. The next question was if free FXIII-A2 was in the nonactivated or active form. To address this question, fibrin clot formation was induced by B moojeni and Ca2+ in immunodepleted plasma. B moojeni cleaves off fibrinopeptide A, but not fibrinopeptide B, from fibrinogen and fails to activate FXIII. The activation of FXIII by thrombin generated in the plasma in the presence of Ca2+ was prevented by hirudin. In such a setup, no fibrin-chain crosslinking occurred, indicating that free FXIII-A2 in the plasma was in the nonactivated form.

Fibrin crosslinking by noncomplexed free FXIII-A2remaining in the plasma after removal of FXIII-A2B2complex by immunodepletion. Plasma was depleted of FXIII-A2B2 and FXIII-B2 by immunoabsorption on Sepharose-linked anti-FXIII-B monoclonal antibody that reacted with both free and complexed FXIII-B. Depleted plasma (DP) and normal plasma (P) were clotted by thrombin (T) in the presence and absence of the FXIIIa inhibitor iodoacetamide (IA). Depleted plasma was also clotted by batroxobin (B) in the presence of the thrombin inhibitor hirudin (H). The fibrin clots were washed and analyzed by SDS-PAGE; fibrin α, β, and γ chains; γ-chain dimers (γ-γ); and high-Mr α-chain polymers (αp) are indicated on the figure. The table below the gel shows the components of the clotting mixture that resulted in the fibrin clot shown on the respective lane.

Fibrin crosslinking by noncomplexed free FXIII-A2remaining in the plasma after removal of FXIII-A2B2complex by immunodepletion. Plasma was depleted of FXIII-A2B2 and FXIII-B2 by immunoabsorption on Sepharose-linked anti-FXIII-B monoclonal antibody that reacted with both free and complexed FXIII-B. Depleted plasma (DP) and normal plasma (P) were clotted by thrombin (T) in the presence and absence of the FXIIIa inhibitor iodoacetamide (IA). Depleted plasma was also clotted by batroxobin (B) in the presence of the thrombin inhibitor hirudin (H). The fibrin clots were washed and analyzed by SDS-PAGE; fibrin α, β, and γ chains; γ-chain dimers (γ-γ); and high-Mr α-chain polymers (αp) are indicated on the figure. The table below the gel shows the components of the clotting mixture that resulted in the fibrin clot shown on the respective lane.

Monoclonal anti-FXIII-B antibody that prevents the interaction between FXIII subunits

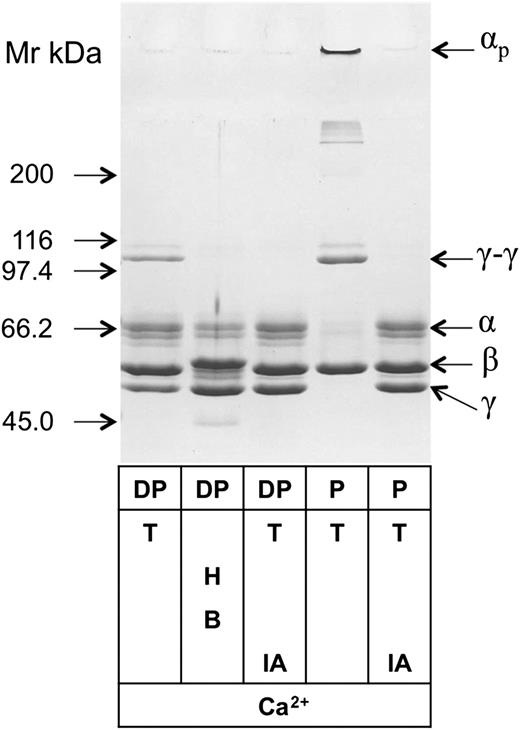

Figure 3A demonstrates the interaction of 2 selected monoclonal anti-FXIII-B antibodies with FXIII-B present in complex and in free form. The immunoprecipitate obtained by anti-FXIII-B(1) antibody cross-reacted with anti-FXIII-A antibody on the western blot, whereas no such cross-reaction was detected when anti-FXIII-B(2) antibody was used for immunoprecipitation. The results clearly indicate that anti-FXIII-B(1) recognizes FXIII-B both in the free and complexed form, whereas anti-FXIII-B(2) reacts only with the free form. Furthermore, preincubation of FXIII-B2 with anti-FXIII-B(2) prevented complex formation with FXIII-A2, whereas anti-FXIII-B(1) had no such effect (Figure 3B).

The differential binding of 2 monoclonal anti-FXIII-B antibodies to complexed and free FXIII-B. (A) FXIII-B was immunoprecipitated from human plasma by 2 monoclonal anti-FXIII-B antibodies and the presence of FXIII-B and FXIII-A, and the immunoprecipitates were detected by western blotting using polyclonal anti-FXIII-B or anti-FXIII-A antibodies on separate blots. FXIII-A was present in the immunoprecipitate obtained by anti-FXIII-B(1) but absent when anti-FXIII-B(2) was used for immunoprecipitation. (B) the concentration-dependent inhibition of FXIII-A2B2 complex formation by anti-FXIII-B(2), but not by anti-FXIII-B(1), antibody was demonstrated in an ELISA-type assay as described in “Effect of anti-FXIII-B antibodies on the interaction of FXIII subunits” in “Methods.” The label on the y-axis (optical density [OD] 450 nm) is a measure of FXIII-A2B2 complex formation.

The differential binding of 2 monoclonal anti-FXIII-B antibodies to complexed and free FXIII-B. (A) FXIII-B was immunoprecipitated from human plasma by 2 monoclonal anti-FXIII-B antibodies and the presence of FXIII-B and FXIII-A, and the immunoprecipitates were detected by western blotting using polyclonal anti-FXIII-B or anti-FXIII-A antibodies on separate blots. FXIII-A was present in the immunoprecipitate obtained by anti-FXIII-B(1) but absent when anti-FXIII-B(2) was used for immunoprecipitation. (B) the concentration-dependent inhibition of FXIII-A2B2 complex formation by anti-FXIII-B(2), but not by anti-FXIII-B(1), antibody was demonstrated in an ELISA-type assay as described in “Effect of anti-FXIII-B antibodies on the interaction of FXIII subunits” in “Methods.” The label on the y-axis (optical density [OD] 450 nm) is a measure of FXIII-A2B2 complex formation.

Epitope mapping for anti-FXIII-B antibodies

rFXIII-B2 was engineered in insect cells. Due to incomplete N-glycosylation, the molecular mass of rFXIII-B2 is somewhat lower than that of its plasma counterpart and rFXIII-B2 moved somewhat faster in SDS gel than FXIII-B2 prepared from plasma (Figure 4, lanes 1 and 2). Plasma and rFXIII-B reacted equally well with anti-FXIII-B(2), whereas there was no reaction with the concentrated supernatant of mock-transfected cells (lane 3). The antibody gave strong reaction with recombinant SD1+2, the combined first 2 N-terminal sushi domains of FXIII-B (lane 4). The results indicate that the antibody interfering with the interaction of FXIII subunits binds to an epitope on SD1+2.

The binding of anti-FXIII-B(2) antibody to recombinant FXIII-B and its combined 1+2 sushi domains (SD1+2). FXIII-B and SD1+2 were expressed in insect cells as described in the text. Cell culture supernatants were concentrated and analyzed by western blotting. Lane 1: FXIII-B isolated from the plasma (the faint band below FXIII-B corresponds to a proteolytic product); lane 2: supernatant of cultured cells expressing rFXIII-B; lane 3: supernatant of mock-transfected cells; lane 4: supernatant of cells expressing SD1+2.

The binding of anti-FXIII-B(2) antibody to recombinant FXIII-B and its combined 1+2 sushi domains (SD1+2). FXIII-B and SD1+2 were expressed in insect cells as described in the text. Cell culture supernatants were concentrated and analyzed by western blotting. Lane 1: FXIII-B isolated from the plasma (the faint band below FXIII-B corresponds to a proteolytic product); lane 2: supernatant of cultured cells expressing rFXIII-B; lane 3: supernatant of mock-transfected cells; lane 4: supernatant of cells expressing SD1+2.

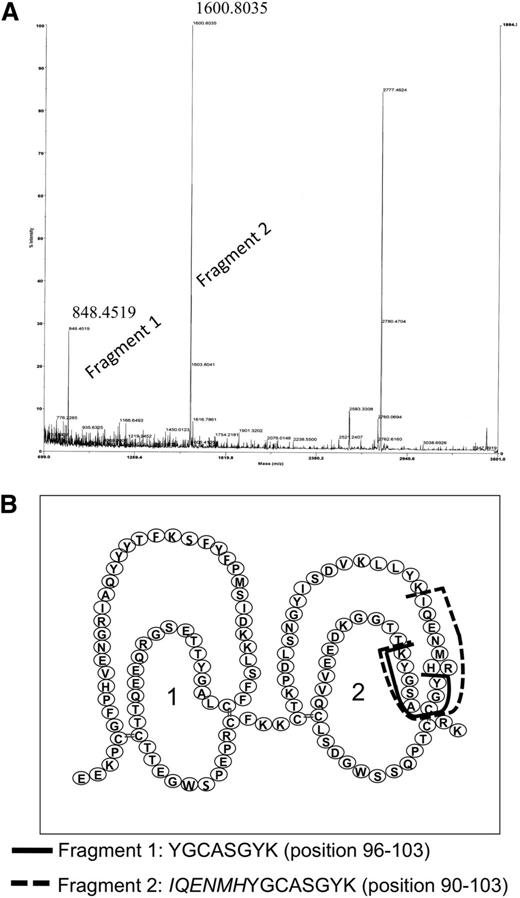

Because efforts to express sushi domains 1 and 2 separately remained unsuccessful, we searched for the epitope reacting with anti-FXIII-B(2) by using a different technique. Anti-FXIII-B(2) was covalently linked to Fc-fragment-specific anti-mouse IgG immobilized on Sepharose gel and incubated with FXIII-B. After exhaustive digestion with trypsin, the fragments that remained attached to anti-FXIII-B(2) were identified by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. We were able to identify 2 tryptic fragments (Figure 5A) with the sequences that correspond to amino acid positions 90 to 103 and 96 to 103 on the second sushi domain (Figure 5B). The presence of these overlapping peptides is explained by the Arg95His FXIII-B polymorphism.16 The frequency of the His95 allele is approximately 7.5% in the white population (International HapMap project; www.hapmap.org), and in the FXIII-B preparation purified from pooled plasma, both variants must have been present. The presence of His at position 95 eliminates a trypsin cleavage site, and instead of the peptide YGCASGYK, a longer peptide with the sequence IQENMHYGCASGYK was recovered. The results locate the epitope for anti-FXIII-B(2) antibody to the octapeptide present in the second sushi domain between positions 96 and 103. Using the same technique, the epitope for anti-FXIII-B(1) antibody, which did not interfere with complex formation, was located to the peptide sequence 405 to 412 (CNEYYLLR) in seventh sushi domain.

Identification of the epitope for anti-FXIII-B(2) antibody on FXIII-B. (A) The tryptic fragments of FXIII-B bound to anti-FXIII-B(2) antibody was identified by MALDI-TOF. The numbers above the peaks corresponding to the 2 fragments represent the measured m/z values. A third major peak at m/z 2777.47 could not be identified in the primary structure of FXIII-B. (B) The amino acid sequence of identified fragments and their location in the primary structure of FXIII-B.

Identification of the epitope for anti-FXIII-B(2) antibody on FXIII-B. (A) The tryptic fragments of FXIII-B bound to anti-FXIII-B(2) antibody was identified by MALDI-TOF. The numbers above the peaks corresponding to the 2 fragments represent the measured m/z values. A third major peak at m/z 2777.47 could not be identified in the primary structure of FXIII-B. (B) The amino acid sequence of identified fragments and their location in the primary structure of FXIII-B.

Discussion

Unequivocal results obtained by 2 different techniques showed that the Kd for the association of the 2 types of FXIII subunit is in the range of 10−10 M, which is magnitudes lower than the values published in earlier reports.15,16 The estimated Kd is in the range of high-affinity antigen-antibody interaction and suggests very tight binding between FXIII-A2 and FXIII-B2. It has been generally accepted that FXIII-A2 in the plasma is fully complexed with FXIII-B. However, calculations based on the estimated Kd and the FXIII subunit concentrations present in the plasma suggested that, in spite of the tight binding, a minor fraction of FXIII-A2 (approximately 1%) exists in the free noncomplexed form. The presence of free FXIII-A2 in plasma was also confirmed experimentally. In tears and CSF at FXIII subunit concentrations a minimum of 3 magnitudes lower than in plasma, the proportion of free FXIII-A2 was much higher. The established Kd was also validated by the fair agreement between calculated and measured free FXIII-A2 in the 3 body fluids.

It was also shown that the measured free FXIII-A2 is neither a degraded nor an activated form of FXIII; it is functionally active, and when activated by thrombin and Ca2+, it can crosslink fibrin. At this stage, one can only offer speculations on the physiological significance of free FXIII-A2 in the plasma. FXIII-A2 in the absence of FXIII-B2 does not need the removal of activation peptide for activation. Noncleaved FXIII-A2 goes through a slow progressive activation at Ca2+ and NaCl concentrations present in the plasma, and fibrinogen might promote this nonproteolytic activation. Years ago, a low-grade “constitutive” fibrin and fibrinogen crosslinking activity of nonactivated pFXIII was described.34 One wonders if this constitutive activity could be associated with the free fraction of FXIII-A2. This presumption seems to be contradicted by the finding that in immunodepleted plasma containing only free FXIII-A2, fibrin formed by batroxobin was not crosslinked. However, any nonproteolytically activated free FXIII-A2 might bind to cellular elements or to fibrin(ogen) fibrils and might be cleared from the plasma. It is also possible that in newly formed fibrin, this more easily activated fraction of pFXIII contributes to the rapid crosslinking of fibrin γ chains, which needs only a minute amount of FXIIIa.35

FXIII-B is N-glycosylated at Asn142 and Asn525, which reside in the third and ninth sushi domains, respectively.36,37 Neither the removal of carbohydrate residues from FXIII-B by neuraminidase or N-glycosidase F nor the different carbohydrate side chain on rFXIII-B expressed in insect cells prevented the formation of A2B2 complex.10,15 In the present experiments, the Kd for the binding of plasma-derived FXIII-B2 to rFXIII-A2 did not differ significantly from the Kd for the interaction of rFXIII-B2 and rFXIII-A2. These findings strongly suggest that the binding epitope(s) responsible for the interaction with FXIII-A2 must reside in the protein part.

To locate the epitope on FXIII-B responsible for the interaction with FXIII-A, Souri et al produced various truncated rFXIII-Bs of various lengths.10 They demonstrated that those truncated FXIII-B subunits that lacked the first sushi domain were not able to form a complex with FXIII-A. Just like us, they were not able to express isolated sushi domain 1. We took a different approach by producing an anti-FXIII-B monoclonal antibody that interacted only with free FXIII-B2 and prevented its complex formation with FXIII-A2. The antibody recognized FXIII-B on western blots; that is, it reacted with a sequential epitope. The finding that it reacted with SD1+2 confirms that the N-terminal part of the molecule is involved in the interaction with FXIII-A2. By the combination of immunoabsorption and MALDI-TOF techniques, it was demonstrated that epitope for the antibody is in the peptide YGCASGYK spanning positions 96 to 103 in the second sushi domain. The other antibody that reacted with the seventh sushi domain failed to influence the interaction of FXIII subunits. The findings of Souri et al and our results suggesting the interaction site for complex formation on the first and second sushi domains of FXIII-B, respectively, are not necessarily contradictory. The lack of the first sushi domain might influence the orientation/configuration of the second sushi domain and distort the binding site. On the other hand, the antibody reacting with the second sushi domain might make the binding site on the first sushi domain inaccessible for FXIII-A2 by steric hindrance. Further experiments are needed to pinpoint the epitope(s) on SD1+2 of FXIII-B that are involved in the formation of FXIII-A2B2 complex.

The combination of the antibodies reacting only with free FXIII-B2 and with both free and complexed FXIII-B2 provides the potential of developing a sandwich ELISA for the measurement of free FXIII-B2 in the plasma. Such an assay could be useful for the determination of rFXIII-A2 binding capacity in substituted patients.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Gizella Haramura and Judit Csapó for excellent technical support.

This work was supported by research grants from the Hungarian Scientific Research Fund and the National Development Agency (CNK80776 and K109543) (L.M.) and by research grants from the Hungarian Academy of Science (MTA11003, TKI227) (L.M.), the National Development Agency (TÁMOP projects 4.2.2.B-10/1-2010-0024, 4.2.2.A-11/1/KONV-2012-0045) (L.M.), and the University of Debrecen Medical and Health Science Center (MEC1/2011) (Z.B.). K.P. is a recipient of an Ányos Jedlik fellowship (National Excellence Program; TÁMOP-4.2.4.A/ 2-11/1-2012-0001), and this work is part of her doctoral thesis. Z.B. is the recipient of János Bólyai fellowship of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences and Lajos Szodoray Prize.

Authorship

Contribution: É.K. performed experiments, designed the study, and wrote the paper; K.P. and Z.B. performed the SPR experiments and analyzed the data; A.C. and Z.Z.O. performed experiments; F.F. performed the mass spectrometry experiments; M.L.U. expressed recombinant proteins; and L.M. designed and supervised the study and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: László Muszbek, Clinical Research Center, University of Debrecen, Medical and Health Science Center, 98 Nagyerdei Krt, 4032 Debrecen, Hungary; e-mail: muszbek@med.unideb.hu.

![Figure 3. The differential binding of 2 monoclonal anti-FXIII-B antibodies to complexed and free FXIII-B. (A) FXIII-B was immunoprecipitated from human plasma by 2 monoclonal anti-FXIII-B antibodies and the presence of FXIII-B and FXIII-A, and the immunoprecipitates were detected by western blotting using polyclonal anti-FXIII-B or anti-FXIII-A antibodies on separate blots. FXIII-A was present in the immunoprecipitate obtained by anti-FXIII-B(1) but absent when anti-FXIII-B(2) was used for immunoprecipitation. (B) the concentration-dependent inhibition of FXIII-A2B2 complex formation by anti-FXIII-B(2), but not by anti-FXIII-B(1), antibody was demonstrated in an ELISA-type assay as described in “Effect of anti-FXIII-B antibodies on the interaction of FXIII subunits” in “Methods.” The label on the y-axis (optical density [OD] 450 nm) is a measure of FXIII-A2B2 complex formation.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/123/11/10.1182_blood-2013-10-533596/2/m_1757f3.jpeg?Expires=1769234082&Signature=by07pp1jWne6hVhdOJpkS3i3IJh00TnMr9xoj6sLdfMkiYv~vheYdowfXAbZQRG9EfeVGe~qaLgZF-ixMVZzBrU0Z~Uk-pTVA45nUcdKQpdWk20CGsRtatn~HSzkRNgY7JzhHo-rnVrYjOTmCiAfZJZ51QDqvb1uXNyuWGoPoJb9iUU~UMci9995aiMWtzvD6w79k0L6VIIiAKgRh0AkVxfb6BkRc75UlO83N44x72mfZrPLERgwRgWkHW9LcxQEbTYPK6ExXCa~RFkLHKK0yoz9shg0VX61DIt6k3lCmeOrpH7wHvEfIXjufCy7XJq3Afj4PCDj6DyK1o0Dj6WMZg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal