Key Points

Myeloid cells in subjects with cancer contain fibrocytes, a cell subset previously implicated in chronic inflammation.

Fibrocytes in cancer patients are immunosuppressive and may contribute to immune escape.

Abstract

Fibrocytes are hematopoietic stem cell–derived fibroblast precursors that are implicated in chronic inflammation, fibrosis, and wound healing. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) expand in cancer-bearing hosts and contribute to tumor immune evasion. They are typically described as CD11b+HLA-DR– in humans. We report abnormal expansions of CD11b+HLA-DR+ myeloid cells in peripheral blood mononuclear fractions of subjects with metastatic pediatric sarcomas. Like classical fibrocytes, they display cell surface α smooth muscle actin, collagen I/V, and mediate angiogenesis. However, classical fibrocytes serve as antigen presenters and augment immune reactivity, whereas fibrocytes from cancer subjects suppressed anti–CD3-mediated T-cell proliferation, primarily via indoleamine oxidase (IDO). The degree of fibrocyte expansion observed in individual subjects directly correlated with the frequency of circulating GATA3+CD4+ cells (R = 0.80) and monocytes from healthy donors cultured with IL-4 differentiated into fibrocytes with the same phenotypic profile and immunosuppressive properties as those observed in patients with cancer. We thus describe a novel subset of cancer-induced myeloid-derived suppressor cells, which bear the phenotypic and functional hallmarks of fibrocytes but mediate immune suppression. These cells are likely expanded in response to Th2 immune deviation and may contribute to tumor progression via both immune evasion and angiogenesis.

Introduction

Tumors evade immune destruction via a panoply of mechanisms, including expansion and recruitment of immunosuppressive cells into their microenvironment.1 Among the most prominent subsets of tumor-induced immunosuppressive cells are myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), a heterogeneous group of immature monocytic and granulocytic cells, which suppress immune responses through a variety of mechanisms including nutrient depletion, oxidative stress, and activation of regulatory T cells (reviewed in Gabrilovich and Nagaraj,2 Serafini et al,3 and Gabrilovich et al4 ). MDSCs are rare in healthy hosts but progressively increase in number in the blood, lymphoid organs, and the tumor microenvironment as tumor burden increases. Murine MDSCs coexpress Gr-1 and CD11b5 and are typically described as monocytic precursors (Ly6C+) or neutrophilic precursors (Ly6G+). Human MDSCs appear to be more heterogeneous but are most commonly described as Lin–CD11b+CD33+HLADR– cells,6-10 with a neutrophilic phenotype in some settings (CD14–CD15+CD66b+)11 and a monocytic phenotype in others (CD14+CD15–CD66b–).3,12-14

The term fibrocyte was coined in 1994 to describe a blood-borne, fibroblastlike cell that is recruited to sites of tissue injury and mediates tissue repair (reviewed in references 15 and 16). Fibrocytes have been described in both mice and humans, where they bear a hematopoietic progenitor phenotype (CD45+CD34+) and produce extracellular matrix proteins. Fibrocytes are rare in healthy hosts but expand in conditions associated with macrophage-driven inflammation and fibroblast activation.17-20 Current concepts hold that fibrocytes mediate proinflammatory effects via their macrophagelike properties, as well as tissue remodeling effects because of their capacity to produce extracellular matrix proteins.21-23 Fibrocytes are also reported to function as antigen-presenting cells, consistent with their expression of MHC class II and CD80/86 and their capacity to secrete a multitude of cytokines.24-27 Fibrocytes have not been previously described in human cancer patients but have recently been implicated in murine cancer, most notably in a study wherein FAP+ fibrocytes were implicated as mediators of tumor immune escape.28

In this study, we report a novel subset of circulating myeloid-derived suppressor cells, expanded in subjects with metastatic pediatric sarcomas but essentially absent from healthy controls. These cells bear hallmark features of fibrocytes including CD45+CD34+HLA-DR+ expression, production of extracellular matrix proteins, and the capacity to induce angiogenesis. Unlike previous reports, however, fibrocytes expanded in cancer subjects mediate immune suppression rather than serving as antigen presenters. The cells demonstrate features of both neutrophilic and monocytic lineages and express indoleamine oxidase, which is primarily responsible for their immunosuppressive properties. Expansion correlates with Th2 deviation in cancer subjects, and similar cells can be readily generated from monocytes obtained from healthy donors using IL-4. We conclude that subjects with metastatic cancer experience expansion of immunosuppressive fibrocytes, which are predicted to augment tumor growth by mediating immune escape and inducing angiogenesis.

Materials and methods

Donors and cells, serum or plasma collection, and cytokine analysis

Peripheral blood lymphocytes and monocytes and sera were obtained from subjects (n = 53; age range 3-33 years) via leukapheresis after informed consent was given and enrollment into the NCI institutional review board–approved clinical trials. All subjects had metastatic pediatric sarcomas (Ewing sarcoma n = 34, alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma n = 19), and cells were analyzed from the subjects either at the time of initial presentation before initiation of any therapy (n= 26) or at the time of recurrent or progressive disease (n = 27) after standard therapy.29,30 Cells and sera were obtained from healthy controls after informed consent was given and enrollment in a National Institutes of Health Clinical Center institutional review board–approved clinical trial.

Monocyte-rich fractions were separated from lymphocyte-rich fractions in apheresis products via countercurrent centrifugal elutriation as previously described.31 To generate fibrocytes in vitro, elutriated monocyte-rich fractions from healthy donors were plated at 106 cells/mL in 20 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) in T75 flasks (Nunc) for 2 hours at 37°C. Nonadherent cells and PBS were removed by gentle pipetting; then AIM V medium (Invitrogen) and the designated cytokines at a concentration of 10 ng/mL (Peprotech) were added. Cultures were incubated for 9 to 12 days and then analyzed for morphology, phenotype, and gene expression.

Flow cytometry, electronic cell sorting, and immunomagnetic bead separation

Cells from monocyte-rich or lymphocyte-rich fractions were cryopreserved, thawed using standard techniques, resuspended in 100 μL of fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) staining solution (PBS containing 0.5% fetal calf serum and 2 mM ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid) and then co-incubated with the appropriate mAb on ice for 30 minutes. For intracellular staining, cells were first fixed and permeabilized (eBioscience). The following fluorochrome or biotin-conjugated monoclonal antibodies were used: PM2K (Abcam); anti-CD11c (clone 3.9), -CD14 (clone M5E2), -CD15 (clone H198), -CD66b (clone G10F5), -CD123 (clone 6H6), -CD127 (clone A019D5), -CD181 (clone 8F1/CXCR1), -HLA-DR (clone L243), -MMP9 (clone F11P2C3), -TSLPR (clone 1B4) (Biolegend); Strepavidin-PE or PerCP/Cy5.5; anti-LSP1 (clone 16/LSP1) (eBioscience); anti-CD33 (clone WM53), anti-GATA3 (clone TWAJ), anti-Foxp3 (clone PCH101) (BD Biosciences); anti-CD33 (clone CD33-4D3), -CD34 (581) (Invitrogen); anti-CD11b (clone M1/70.15.11.5) (Miltenyi Biotec); 25F9 (CD163), anti-S100A8/A9 (27E10) (Novus Biologicals); anti-αSMA (clone 1A4), -CD124 (BAF230), anti-hFibronectin (clone P1F11) (R&D); and anti-collagen I (600-406-103), anti-collagen V (600-406-107) (Rockland). Flow cytometry was performed using FACS Aria II using FACS Diva software (Becton Dickinson) and analyzed by FlowJo 9.6 (Treestar). FACS sorting was also performed using FACS Aria II and resulted in consistent purities >90%.

For cytospin analysis, electronically sorted cells were spun on a glass slide, fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde, stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and analyzed by conventional light microscopy. For immunomagnetic bead selection, IL4-treated monocytes cultured for 9 to 10 days were incubated with Dynabeads CD14 (11149D; Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s recommendation. CD14– fibrocytes were negatively selected by removal of Dynabeads-bound CD14+ cells using a magnetic particle concentrator.

Proliferation and suppression assays

Lymphocytes were plated in triplicate at 5 × 104 cells/well in 96-well flat-bottomed plates (Nunc), which had been previously coated with the designated concentrations of OKT3 (Orthoclone). Cultures were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 3 to 5 days and then cell proliferation was measured by incorporation of 3H-thymidine (1 μCi/well, Perkin Elmer) after a 16- to 18-hour pulse using a microplate scintillation counter (Top Count; Packard). Suppression assays used electronically sorted cell subsets or immunomagnetically separated subsets as designated and were performed at a ratio of 1 suppressor: 2 T cells, and proliferation was measured in the presence or absence of 20 μM 1-MT (Sigma), an IDO inhibitor.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction analysis

Total RNA was extracted using an RNeasy mini extraction kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. First-strand cDNAs were synthesized using oligodT primers and SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed on an ABI PRISM 7000 using primers and probes of genes of interest (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative values of genes of interest were normalized to β-actin using the ΔΔCt method.32

Tube formation assay

Angiogenesis was analyzed by seeding 1.5 × 104 human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) (Lonza) and 2 × 104 patient monocytes, or fibrocytes in 1% serum per well in 96 flat-bottomed well plates coated with growth factor–reduced Matrigel (BD Biosciences), then incubating them at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere for 18 hours. Fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-2 (PeproTech) was added at 25 ng/mL instead of cells where designated as a positive control. Formation of capillarylike tubular structures was visualized and compared using 40× original magnification. The total number of branch points was calculated for each well as previously described.33

Expression profiling and gene set enrichment analysis

RNA was extracted from electronically sorted CD14+ vs CD14– cells using the Qiagen RNeasy mini-kit as described before. Purified RNA was analyzed for gene expression using the Nugen WT Ovation labeling kit with Affymetrix human U133 plus 2.0 array. Gene set enrichment analysis was conducted as described previously.34,35 Lindset dendritic cell maturation data sets B and C comprise genes expressed during reprogramming of dendritic cells during maturation36 and contain genes known to regulate responses of both innate immune cells and lymphocytes. The Rutella gene set comprises genes expressed by human growth factor–activated monocytes, which possess toleragenic properties.37

Statistical analysis

Tests were performed using GraphPad Prism 5 software. Comparisons between 2 groups were done using a 2-tailed unpaired Student t test, with significance determined as P < .05. A 2-way analysis of variance was performed for multiple comparisons. Correlations were calculated using the Spearman R coefficient.

Results

Patients with metastatic pediatric sarcomas have expanded numbers of circulating fibrocytes

MDSC expansion has been described in numerous murine and human cancers.2-4 We investigated whether MDSCs were expanded in monocyte-rich fractions obtained via apheresis from 53 subjects with metastatic Ewing sarcoma or rhabdomyosarcoma (details contained in supplemental Table 1).29,30 As shown in Figure 1A, cancer-bearing subjects had an abnormal population of CD14–CD11chiCD123– cells, whereas healthy donors showed few such cells (blue box). This population is distinct from monocytes (red box), myeloid dendritic cells (green polygon), and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (orange box). Overall, 52 of 53 subjects we studied demonstrated expansions that were greater than 2 SD beyond the mean found in healthy donors, with a wide range in the degree of expansion observed (Figure 1B) in the patient population. We observed no relationship between the degree of CD14–CD11chiCD123– cell expansion and histology, age, history of previous cytotoxic chemotherapy, and survival outcome (data not shown). Because all subjects studied had high tumor burdens and metastatic disease, we could not assess the relationship between this CD14–CD11chiHLA-DR+ population expansion and tumor burden/or metastases.

Expansion of a novel myeloid cell subset in cancer patients. (A) In cancer patients, gating on CD14– cells in monocyte-rich fractions elutriated from apheresis products showed expansion of CD11chiCD123– cells (blue box) that are not present in healthy donors. The green box denotes myeloid dendritic cells and the orange box denotes plasmacytoid dendritic cells. The CD14+ fraction is comprised entirely of monocytes (red box) in patients and healthy donors. (B) Percent of CD11c+CD123– cells in the patient cohort (n = 53) vs healthy donors (n = 10). The red dotted line represents the mean, and the error bar represents the SEM. (C) Expression profiles of gated subsets (color coded) are shown. CD11chiCD123–CD14– cells express common MDSC markers, including CD11b, CD15, CD66b, and CD124, but they also express HLA-DR and CD127. Quadrants set based on the background fluorescence using fluorescence minus one (FMO) controls. Representative flow cytometry plots from a representative subject are shown. (D) Hematoxylin and eosin–stained cytospins of electronically sorted subsets (original magnification ×200) from a representative subject. CD11chiCD123–CD14– cells resemble immature monocytes, whereas other subsets show the expected morphology.

Expansion of a novel myeloid cell subset in cancer patients. (A) In cancer patients, gating on CD14– cells in monocyte-rich fractions elutriated from apheresis products showed expansion of CD11chiCD123– cells (blue box) that are not present in healthy donors. The green box denotes myeloid dendritic cells and the orange box denotes plasmacytoid dendritic cells. The CD14+ fraction is comprised entirely of monocytes (red box) in patients and healthy donors. (B) Percent of CD11c+CD123– cells in the patient cohort (n = 53) vs healthy donors (n = 10). The red dotted line represents the mean, and the error bar represents the SEM. (C) Expression profiles of gated subsets (color coded) are shown. CD11chiCD123–CD14– cells express common MDSC markers, including CD11b, CD15, CD66b, and CD124, but they also express HLA-DR and CD127. Quadrants set based on the background fluorescence using fluorescence minus one (FMO) controls. Representative flow cytometry plots from a representative subject are shown. (D) Hematoxylin and eosin–stained cytospins of electronically sorted subsets (original magnification ×200) from a representative subject. CD11chiCD123–CD14– cells resemble immature monocytes, whereas other subsets show the expected morphology.

As with previously reported MDSCs, Figure 1C demonstrates that the abnormal population is CD11b+CD15+CD66b+ and expresses CD124 (IL4Rα); however, the cells are distinct from previously reported MDSCs based on high expression of HLA-DR, CD127 (IL7Rα) and low/absent expression of CD33. Morphologically, the abnormal population resembles immature myeloid cells of the monocyte lineage (Figure 1D). Thus, we observe cancer-related expansion of a unique population of HLA-DR+ cells with physical and morphologic characteristics of immature monocytes, and a cell surface expression profile that bears features of neutrophilic myeloid-derived suppressor cells.

High expression of HLA-DR on this population led us to question whether this subset bore features of fibrocytes, blood-borne fibroblast precursors associated with chronic inflammation that are known to express MHC class II. Indeed, further analysis revealed that the majority of cells in the abnormal myeloid subset expressed αSMA, collagen I+/V+ CD34+, MMP9, S100A8/A9, fibronectin, and LSP-1, consistent with a fibrocyte lineage38 (Figure 2A, supplemental Figure 2). Monocytes, myeloid DCs, or plasmacytoid DCs did not express αSMA or collagen I+/V+. Furthermore, fibrocytes did not express CD163 or PM-2K, thus distinguishing them from macrophages (Figure 2A, supplemental Figure 1B). Interestingly, the fibrocytes also expressed TSLPR and variably expressed CXCR1. We next tested these cells for their capacity to mediate angiogenesis, a property attributed to fibrocytes.39,40 Electronically sorted CD14–CD11chiCD123– cells obtained from cancer-bearing subjects induced cell dose–dependent new vessel development in a standard tube formation assay, whereas similar effects were not induced by CD14+ monocytes from the same subject (Figure 2B-C). Thus, subjects with metastatic cancer show expanded populations of circulating fibrocytes that mediate angiogenesis and bear some phenotypic features in common with previously described myeloid-derived suppressor cells.

Expanded CD11chiCD123–CD14– cells are fibrocytes that mediate angiogenesis. (A) Using the same gating strategy as shown in Figure 1A, CD11chiCD123–CD14– cells from a representative subject sample were analyzed for cell surface phenotype. The shaded areas represent background fluorescence on the designated population as indicated by FMO controls. This is representative of more than 10 experiments. (B) Comparison of tube formation by both electronically sorted CD11chiCD123–CD14– cells (designated fibrocytes) and CD14+ monocytes from 1 representative cancer subject, which were then plated in an angiogenesis assay. HUVEC cultures in FGF-2 were used as a positive control. This is representative of 5 experiments. (C) Mean ± SEM joint counts formed by HUVEC cocultured with FGF-2, monocytes vs fibrocytes in 5 separate tube formation assays using fibrocytes, and monocytes from 5 separate subjects.

Expanded CD11chiCD123–CD14– cells are fibrocytes that mediate angiogenesis. (A) Using the same gating strategy as shown in Figure 1A, CD11chiCD123–CD14– cells from a representative subject sample were analyzed for cell surface phenotype. The shaded areas represent background fluorescence on the designated population as indicated by FMO controls. This is representative of more than 10 experiments. (B) Comparison of tube formation by both electronically sorted CD11chiCD123–CD14– cells (designated fibrocytes) and CD14+ monocytes from 1 representative cancer subject, which were then plated in an angiogenesis assay. HUVEC cultures in FGF-2 were used as a positive control. This is representative of 5 experiments. (C) Mean ± SEM joint counts formed by HUVEC cocultured with FGF-2, monocytes vs fibrocytes in 5 separate tube formation assays using fibrocytes, and monocytes from 5 separate subjects.

Fibrocytes circulating in cancer patients mediate T-cell immunosuppression via IDO

Several groups have reported that fibrocytes serve as antigen-presenting cells.24,25 We therefore examined the capacity of fibrocytes expanded in cancer patients to enhance T-cell proliferation after stimulation with suboptimal concentrations of anti-CD3. Although the addition of electronically sorted CD14+ monocytes or myeloid DCs to populations of enriched T cells enhanced anti–CD3-induced T-cell proliferation, electronically sorted fibrocytes from cancer-bearing subjects did not enhance T-cell proliferation in this assay (Figure 3A). Further, when fibrocytes were added to T cell cultures (fibrocyte:T-cell ratio of 1:2) with concentrations of anti-CD3 sufficient to induce T-cell activation, we observed suppression of T-cell proliferation (Figure 3B). Therefore, unlike conventional fibrocytes described in states of chronic inflammation and wound healing, fibrocytes circulating in cancer subjects possess immunosuppressive properties.

Fibrocytes mediate immune suppression via IDO. (A) Fibrocytes do not co-stimulate T cells treated with submitogenic concentrations of anti-CD3. Elutriated lymphocytes (5 × 104 cells/well) and designated electronically sorted cell subsets (2.5 × 104 cells/well) were added to a 96-well plate precoated with the designated concentration of anti-CD3, and thymidine incorporation was measured on day 3. This is representative of 5 experiments using cells from 5 separate subjects. (B) Suppression of anti–CD3-mediated T-cell proliferation by fibrocytes. T cells were plated as in (A), but the designated electronically sorted cell subsets (purity >90%) were added (2.5 × 104 cells/well) at a ratio of 2 lymphocytes:1 suppressor, and thymidine incorporation was measured on day 3. This is representative of 6 experiments using cells from 6 separate subjects. (C) Semiquantitative real-time PCR was used to measure IDO, Arginase I, and INOS2. Relative amounts compared with normal peripheral blood mononuclear cells are shown. The mean ± SEM was derived from 6 experiments. (D) Fibrocyte-mediated suppression can be reversed by the addition of an IDO inhibitor, 1MT. Cultures were set up as described in (A) and, where designated, 1MT was added at a concentration of 20 μM at the beginning on the co-culture. Results are representative of 5 experiments using fibrocytes from 5 separate subjects. All experiments in Figure 3 used electronically sorted fibrocytes with purity >90%.

Fibrocytes mediate immune suppression via IDO. (A) Fibrocytes do not co-stimulate T cells treated with submitogenic concentrations of anti-CD3. Elutriated lymphocytes (5 × 104 cells/well) and designated electronically sorted cell subsets (2.5 × 104 cells/well) were added to a 96-well plate precoated with the designated concentration of anti-CD3, and thymidine incorporation was measured on day 3. This is representative of 5 experiments using cells from 5 separate subjects. (B) Suppression of anti–CD3-mediated T-cell proliferation by fibrocytes. T cells were plated as in (A), but the designated electronically sorted cell subsets (purity >90%) were added (2.5 × 104 cells/well) at a ratio of 2 lymphocytes:1 suppressor, and thymidine incorporation was measured on day 3. This is representative of 6 experiments using cells from 6 separate subjects. (C) Semiquantitative real-time PCR was used to measure IDO, Arginase I, and INOS2. Relative amounts compared with normal peripheral blood mononuclear cells are shown. The mean ± SEM was derived from 6 experiments. (D) Fibrocyte-mediated suppression can be reversed by the addition of an IDO inhibitor, 1MT. Cultures were set up as described in (A) and, where designated, 1MT was added at a concentration of 20 μM at the beginning on the co-culture. Results are representative of 5 experiments using fibrocytes from 5 separate subjects. All experiments in Figure 3 used electronically sorted fibrocytes with purity >90%.

To explore the mechanism responsible for fibrocyte-mediated T-cell suppression, we measured expression of IDO, tryptophan-2,3-dioxygenase (TDO), Arg1, and iNOS2 in this cell subset. As shown in Figure 3C, fibrocytes express high levels of IDO, whereas CD14+ monocytes, myeloid DCs, and plasmacytoid DCs expressed little IDO, and none of these subsets expressed substantial levels of Arg1 or iNOS2. Notably, none of these subsets expressed measureable TDO. Fibrocyte-mediated suppression of T-cell proliferation was also significantly inhibited by the addition of 1-methyl tryptophan (1MT) (Figure 3D), an inhibitor of IDO-mediated immunosuppression.41 Thus, IDO plays a role in fibrocyte-mediated immune suppression.

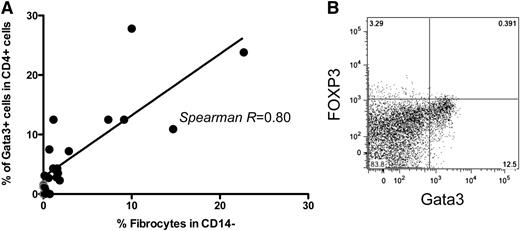

GATA3+ T cells are associated with the appearance of immunosuppressive fibrocytes in cancer subjects

Several reports have implicated Th2 cytokines, including IL-4 and IL-13, in fibrocyte differentiation.23,42 We hypothesized that alterations in the cytokine milieu and/or helper T-cell polarization of subjects with pediatric sarcomas could contribute to expansion of immunosuppressive fibrocytes in this setting. Given that there was a wide range of fibrocyte expansion observed in our subject cohort, we assessed whether the degree of fibrocyte expansion correlated with the degree of Th2 deviation present, as measured by GATA3 expression in CD4+ T cells. We observed a direct correlation between the magnitude of fibrocyte expansion and the percent of CD4+ T cells expressing GATA3+ T cells (Figure 4A-B), whereas there was no relationship between fibrocyte expansion and expression of other measured CD4+ transcription factors, which included T-bet, FOXP3, or RORγt factors (data not shown). Despite this relationship, we did not detect elevations in Th2 cytokines such as IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13, in the sera of subjects with elevated frequencies of fibrocytes or GATA3-expressing CD4+ T cells (data not shown).

Frequency of circulating fibrocytes in cancer subjects correlates with the expansion of circulating GATA3+CD4+ T cells. (A) Correlation between % fibrocytes in the monocyte-rich apheresis fraction and GATA3+CD4+ T cells in the lymphocyte-rich apheresis fraction acquired simultaneously. Each closed dot represents a value measured in an individual subject from whom adequate simultaneous monocyte-rich and lymphocyte-rich samples were available (n = 22 subjects). Gray dots represent results from normal donors (P < .05). (B) Representative flow cytometry dot plot illustrating high levels of GATA3+CD4+ T cells from 1 subject with simultaneous fibrocyte expansion. CD4+ cells were analyzed immediately after thawing and permeabilization without stimulation.

Frequency of circulating fibrocytes in cancer subjects correlates with the expansion of circulating GATA3+CD4+ T cells. (A) Correlation between % fibrocytes in the monocyte-rich apheresis fraction and GATA3+CD4+ T cells in the lymphocyte-rich apheresis fraction acquired simultaneously. Each closed dot represents a value measured in an individual subject from whom adequate simultaneous monocyte-rich and lymphocyte-rich samples were available (n = 22 subjects). Gray dots represent results from normal donors (P < .05). (B) Representative flow cytometry dot plot illustrating high levels of GATA3+CD4+ T cells from 1 subject with simultaneous fibrocyte expansion. CD4+ cells were analyzed immediately after thawing and permeabilization without stimulation.

IL-4 differentiation of monocytes into immunosuppressive CD14– fibrocytes is enhanced by TSLP and fibrocytes can be distinguished from macrophages based on phenotype and gene expression profile

Previous studies have demonstrated that IL-4 can induce monocytes to differentiate into fibrocytes, but such cells have not been described to mediate immunosuppression.23 We therefore explored the ability for IL-4–induced fibrocytes, generated via differentiation of monocytes from healthy donors, to mediate immune suppression and to compare these cells with macrophages generated in these same cultures. Consistent with previous reports,20 monocytes from healthy donors cultured for 9 to 12 days with rhIL-4 generated a population of adherent cells, some of which showed a fibroblastic-appearing spindle shape previously reported for fibrocytes (Figure 5A). Phenotypic analysis revealed that these cells could be divided into CD14+ vs CD14– subsets and that, similar to the results found in circulating monocytic populations from cancer subjects, CD14– cells expressed high levels of collagen and TSLPR, consistent with a fibrocyte phenotype (Figure 5B). Although rhIL-7 did not affect fibrocyte generation (data not shown), the addition of TSLP to IL-4 significantly increased the number of CD14– fibrocytes generated in this system (Figure 5C), thus implicating TSLP as a growth factor for this cell subset. To identify whether rhIL-4–induced, monocyte-derived fibrocytes mediate T-cell suppression, we measured expression of IDO, TDO, ARG1, and iNOS2 in the CD14+ vs CD14– differentiated populations. As with fibrocytes circulating in subjects with metastatic cancer, IDO was highly expressed in rhIL-4–differentiated CD14– fibrocytes (Figure 5D), and rhIL-4–differentiated fibrocytes suppressed anti–CD3-mediated T-cell proliferation (Figure 5E). Therefore, rhIL-4 induces monocyte differentiation into immunosuppressive fibrocytes, which demonstrate a phenotype and functional profile similar to fibrocytes that circulate in subjects with pediatric solid tumors.

IL-4 induces monocytes to differentiate into CD14– fibrocytes that are readily distinguished from CD14+ macrophages in the same culture. (A) Culture of monocyte-rich apheresis fractions from healthy donors with rhIL-4 induces differentiation into an adherent population that contains cells with a typical spindlelike appearance, consistent with a fibrocyte lineage (original magnification ×20). (B) Cell surface phenotype of IL-4–differentiated adherent cells identifies 2 subsets based on CD14 expression, which further shows differential expression of collagen and TSLPR. FMO controls on gated CD14+ vs CD14– populations are shown by shaded gray histograms. This is representative of more than 5 experiments from 5 separate healthy donors. (C) Fibrocyte (defined as CD14–CD123–CD11c+) numbers in monocyte cultures incubated for 9 days with rhIL-4 alone (10 ng/mL) vs rhIL-4 plus TSLP (10 ng/mL). This is representative of 4 separate experiments. (D) CD14+ macrophages vs CD14– fibrocytes generated using rhIL-4 as described in (C) were analyzed by reverse transcriptase PCR for IDO, TDO, ARG1, and INOS2. The mean ± SEM of relative increases normalized to PBMC are shown from 5 separate experiments. (E) RhIL4-induced fibrocytes suppress autologous T-cell proliferation to various concentrations of anti-CD3. Comparisons between 2 groups (with T-cell-alone group) were done using a 2-way analysis of variance for multiple comparisons, with significance determined as P < .05. This is representative of 3 experiments. (F) Using RNA expression profiles of cells generated and electronically sorted as described in (C), gene set enrichment analysis of CD14+ macrophages vs CD14– fibrocytes for the Lindstedt DC maturation C gene set is shown. The most underexpressed of 49 genes in CD14– fibrocytes vs the CD14+ macrophages is listed below the figure. This is representative of 3 separate expression profile-based analyses.

IL-4 induces monocytes to differentiate into CD14– fibrocytes that are readily distinguished from CD14+ macrophages in the same culture. (A) Culture of monocyte-rich apheresis fractions from healthy donors with rhIL-4 induces differentiation into an adherent population that contains cells with a typical spindlelike appearance, consistent with a fibrocyte lineage (original magnification ×20). (B) Cell surface phenotype of IL-4–differentiated adherent cells identifies 2 subsets based on CD14 expression, which further shows differential expression of collagen and TSLPR. FMO controls on gated CD14+ vs CD14– populations are shown by shaded gray histograms. This is representative of more than 5 experiments from 5 separate healthy donors. (C) Fibrocyte (defined as CD14–CD123–CD11c+) numbers in monocyte cultures incubated for 9 days with rhIL-4 alone (10 ng/mL) vs rhIL-4 plus TSLP (10 ng/mL). This is representative of 4 separate experiments. (D) CD14+ macrophages vs CD14– fibrocytes generated using rhIL-4 as described in (C) were analyzed by reverse transcriptase PCR for IDO, TDO, ARG1, and INOS2. The mean ± SEM of relative increases normalized to PBMC are shown from 5 separate experiments. (E) RhIL4-induced fibrocytes suppress autologous T-cell proliferation to various concentrations of anti-CD3. Comparisons between 2 groups (with T-cell-alone group) were done using a 2-way analysis of variance for multiple comparisons, with significance determined as P < .05. This is representative of 3 experiments. (F) Using RNA expression profiles of cells generated and electronically sorted as described in (C), gene set enrichment analysis of CD14+ macrophages vs CD14– fibrocytes for the Lindstedt DC maturation C gene set is shown. The most underexpressed of 49 genes in CD14– fibrocytes vs the CD14+ macrophages is listed below the figure. This is representative of 3 separate expression profile-based analyses.

To further investigate the CD14– subset and to more directly assess its distinction from the CD14+ macrophages generated in this model, we undertook 3 independent experiments to compare gene expression in electronically sorted CD14+ vs CD14– subsets. Each experiment was independently analyzed by gene set enrichment analysis as previously described.34,43 Only 3 gene sets were significantly differentially expressed in all 3 experiments, and each differentially expressed gene set comprised genes associated with dendritic cell maturation. In each case, dendritic cell maturation–associated genes were significantly underexpressed in the CD14– fibrocytes compared with the CD14+ macrophages (Table 1). Figure 5F shows a representative snapshot of an enrichment plot with the 49 most underexpressed genes in all 3 CD14– fibrocyte samples. This result confirms fundamental distinctions between CD14– fibrocytes and CD14+ macrophages and is consistent with a model wherein fibrocytes represent a cell subset with reduced antigen-presenting cell capacity compared with macrophages.

Gene set enrichment analysis of CD14– fibrocytes vs CD14+ macrophages

| GSEA gene set . | Exp # . | NES . | % Overlap with gene set . | FDR . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lindstedt DC Maturation C (66 genes) | 1 | −2.7 (1st) | 74 | 0.000 | .000 |

| 2 | −2.6 (1st) | 79 | 0.000 | .000 | |

| 3 | −2.6 (1st) | 62 | 0.000 | .000 | |

| Rutella response to HGF (236 genes) | 1 | −2.6 (2nd) | 48 | 0.000 | .000 |

| 2 | −2.3 (3rd) | 50 | 0.000 | .000 | |

| 3 | −2.2 (9th) | 37 | 0.000 | .000 | |

| Lindstedt DC Maturation B (50 genes) | 1 | −2.4 (3rd) | 64 | 0.000 | .000 |

| 2 | −2.2 (4th) | 54 | 0.000 | .000 | |

| 3 | −2.2 (7th) | 44 | 0.000 | .000 |

| GSEA gene set . | Exp # . | NES . | % Overlap with gene set . | FDR . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lindstedt DC Maturation C (66 genes) | 1 | −2.7 (1st) | 74 | 0.000 | .000 |

| 2 | −2.6 (1st) | 79 | 0.000 | .000 | |

| 3 | −2.6 (1st) | 62 | 0.000 | .000 | |

| Rutella response to HGF (236 genes) | 1 | −2.6 (2nd) | 48 | 0.000 | .000 |

| 2 | −2.3 (3rd) | 50 | 0.000 | .000 | |

| 3 | −2.2 (9th) | 37 | 0.000 | .000 | |

| Lindstedt DC Maturation B (50 genes) | 1 | −2.4 (3rd) | 64 | 0.000 | .000 |

| 2 | −2.2 (4th) | 54 | 0.000 | .000 | |

| 3 | −2.2 (7th) | 44 | 0.000 | .000 |

NES, normalized enrichment score (rank in all gene sets evaluated for the experiment); FDR, false discovery rate HGF, Hepatocyte Growth Factor.

Discussion

Fibrocytes comprise a well-described cell lineage that shares characteristics of both macrophages and fibroblasts, and has been implicated in chronic inflammation, wound healing, and fibrosis.15 Inflammation is increasingly recognized as a cofactor in oncogenesis,43,44 and emerging concepts hold that cancers share many characteristics of nonhealing wounds. Given that fibrocytes accumulate in states of chronic inflammation, it is not surprising that fibrocytes are expanded in subjects with cancer. Nonetheless, there are only limited reports implicating fibrocytes in cancer pathogenesis. A recent murine model using a reporter mouse to identify fibroblast activation protein (FAP)–expressing cells demonstrated that some FAP+ cells bear a fibrocyte phenotype and accumulate in the microenvironment of solid tumors.28 Depletion of FAP+ cells in this model enhanced the efficacy of immunotherapy, thus indirectly implicating FAP+ fibrocytes in tumor-immune evasion.

Cancer induces a broad network of immunosuppression that favors immune evasion and tumor cell growth. Among the major mediators of tumor immune evasion are FOXP3+ regulatory T cells, TGF-β, IL-10, and MDSCs. MDSCs comprise a heterogeneous group of cells that include granulocytic MDSCs, monocytic MDSCs, tumor-associated macrophages, and immature dendritic cells.45 Fibrocytes express a phenotype that overlaps with previously described myeloid-derived suppressor cells (CD34+CD33lo/–CD15+CD66b+IL4Rα+) but is distinct with regard to expression of HLA-DR, CD127, TSLPR, α–smooth muscle actin, and collagens. Moreover, T-cell suppression mediated by MDSCs has classically been attributed to Arg1 and iNOS2, whereas fibrocytes produced IDO, and immunosuppression was significantly diminished by IDO inhibition. Still, it remains possible that fibrocytes also mediate immunosuppression via other pathways, and this is an area that deserves further study. Regardless of the mechanisms involved, we conclude that fibrocytes represent a novel myeloid-derived suppressor cell subset.

This study is the first to demonstrate expansion of fibrocytes in subjects with cancer and the first to demonstrate T-cell immunosuppression via fibrocytes. On this basis, we propose a nomenclature that distinguishes between conventional immune-activating F1 fibrocytes, which have been described in the setting of benign disease and the immunosuppressive F2 fibrocytes described here. This extends the M1/M2 paradigm of macrophage differentiation46,47 and the N1/N2 paradigm of neutrophil differentiation,48,49 which have been used to discriminate between other immunostimulatory and immunosuppressive myeloid subsets. Our data demonstrates that expansion of GATA3+CD4+ T cells correlate with the expansion of fibrocytes in this subject population and confirm previous work, demonstrating that rhIL-4 is sufficient to induce F2-immunosuppressive fibrocytes from monocytes obtained from healthy donors. These results implicate IL-4 in the induction of this lineage and are reminiscent of IL-4’s essential role in inducing M2 macrophage differentiation.50 Interestingly, rhIL-13, a cytokine that has also been associated with M2 macrophage differentiation also induces fibrocytes that are phenotypically indistinguishable from rhIL-4–induced fibrocytes, but IL-13–induced fibrocytes expressed less IDO than IL-4–induced fibrocytes and mediated less potent immune suppression (data not shown). We also provide the novel observation that TSLPR and IL7Rα are expressed by fibrocytes, and we observed increased numbers of fibrocytes generated ex vivo in the presence of TSLP, but not IL-7. TSLP has already been implicated in immune evasion in murine tumor models via the induction of Th2 polarization, and these results raise the prospect that TSLP may act in part by the generation of immunosuppressive fibrocytes.51-53

The relationship between fibrocytes and macrophages is not clearly defined in the literature, and some features of these subsets have overlapping properties. We contend that the fibrocytes identified in this report are distinct from macrophages based on several features. First, the fibrocytes circulate in large numbers in patients with pediatric sarcoma, whereas macrophages reside in the tissue and do not circulate in large numbers. Second, macrophages have been consistently reported to express CD163 and PM-2K,38 whereas the fibrocytes identified in this report do not express these markers. Third, using an IL-4–based monocyte differentiation model, we generated 2 distinct subsets: (1) a subset comprising CD14+ cells that appeared typical of macrophages, and (2) CD14– cells expressing features consistent with an F2 fibrocyte lineage, including high levels of surface expression of collagens. Notably, TSLPR expression also served to distinguish CD14– fibrocytes from CD14+ macrophages in this model system. Finally, direct comparison of gene expression profiles between CD14+ vs CD14– cells generated from healthy donor monocytes demonstrated that these subsets are quite distinct with regard to expression of genes associated with dendritic cell maturation. Such genes are significantly underexpressed in CD14– fibrocytes compared with CD14+ macrophages, further implicating fibrocytes as an immunosuppressive subset.

In summary, we report that a novel subset of immunosuppressive fibrocytes, which we have termed F2 fibrocytes, expand in subjects with metastatic cancer. These cells have characteristics of myeloid-derived suppressor cells but also possess angiogenic properties and likely contribute to the immune-evasive microenvironment in solid tumors. F2 fibrocytes mediate immunosuppression primarily via IDO and are readily inducible from healthy monocytes by prolonged culture with rhIL4. Future studies are needed to more fully characterize the signaling pathways responsible for fibrocyte polarization and to further study the role of these cells in oncogenesis and tumor-immune evasion.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Dr Joost Oppenheim, who suggested using the F2 concept to describe this population of immunosuppressive fibrocytes, and Dr Tim Greten for his careful review of the manuscript. They also thank the patients who enrolled in the clinical trials and provided the source of these cells.

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute.

Authorship

Contribution: H.Z., I.M., M.J.D., and R.N.K. conducted experiments; H.Z. and C.L.M. analyzed data; J.K. and R.J.O. analyzed gene chip data; C.L.M. provided resources and edited the manuscript; and H.Z. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Crystal L. Mackall, Immunology Section, Pediatric Oncology Branch, NCI, Bldg 10-CRC, 1W-3750, 10 Center Dr, MSC 1928, Bethesda, MD 20892; e-mail: cm35c@nih.gov.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal