Key Points

For patients with acute myelogenous leukemia, post-transplant survival is not determined by donor source (unrelated vs related).

However, for patients with myelodysplastic syndromes, donor source remains an important determinant of post-transplantation outcomes.

Abstract

Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) from human leukocyte antigen (HLA) matched related donor (MRD) and matched unrelated donors (MUD) produces similar survival for patients with acute myelogenous leukemia. Whether these results can be extended to patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) is unknown. Therefore, analysis of post-HCT outcomes for MDS was performed. Outcomes of 701 adult MDS patients who underwent HCT between 2002 and 2006 were analyzed (MRD [n = 176], 8 of 8 HLA-A, -B, -C, -DRB1 allele matched MUD [n = 413], 7 of 8 MUD [ n = 112]). Median age was 53 years (range, 22-78 years). In multivariate analyses, MRD HCT recipients had similar disease free survival (DFS) and survival rates compared with 8 of 8 MUD HCT recipients (relative risk [RR] 1.13 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.91-1.42] and 1.24 [95% CI 0.98-1.56], respectively), and both MRD and 8 of 8 MUD had superior DFS (RR 1.47 [95% CI 1.10-1.96] and 1.29 [95% CI 1.00-1.66], respectively) and survival (RR 1.62 [95% CI 1.21-2.17] and 1.30 [95% CI 1.01-1.68], respectively) compared with 7 of 8 MUD HCT recipients. In patients with MDS, MRD remains the best stem cell source followed by 8 of 8 MUD. Transplantation from 7 of 8 MUD is associated with significantly poorer outcomes.

Introduction

Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) are acquired myeloid clonal disorders of the hematopoietic precursors. Although MDS represents a heterogeneous group of diseases, early in their course they share manifestations of ineffective hematopoiesis and, if left untreated, most patients ultimately die of complications of their cytopenias or from progression to acute myelogenous leukemia (AML).1,2

The prognosis of patients with MDS, as determined by the international prognostic scoring system (IPSS)2 and the more recently reported IPSS-R,3 can guide clinicians and patients in determining the optimal risk-adapted treatment strategy. Cutler et al4 performed a Markov model decision analysis to determine the optimal timing of myeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) from human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-matched related donors (MRD) in patients who were <60 years of age. This analysis, which predated the widespread use of hypomethylating agents, demonstrated that proceeding immediately to HCT was preferred for patients with intermediate-2/high-risk IPSS score, whereas a delayed HCT strategy in those with low-risk/intermediate-1 IPSS until the patient’s disease progressed, produced the longest quality adjusted life expectancy. In a recent analysis, the results were extended to patients aged 60 to 70 years with de novo MDS undergoing T-cell replete reduced intensity conditioning allogeneic HCT. Sixty five percent were recipients of unrelated donor grafts. Outcomes of transplantation were compared with the outcomes of patients that received either the best supportive care, growth factors, or hypomethylating agents. The Markov model-based analysis demonstrated that for intermediate-2/high-risk patients, an early HCT strategy is preferred, whereas delayed HCT is preferred for those with low-risk/intermediate-1 disease.5

The decision to recommend HCT is a complex one and requires proper understanding of the disease, the expected outcome with available treatment options, and the impact of different donor sources on post-HCT outcomes that will help to provide an informed decision. For AML, a prior analysis of HCT outcomes in 2223 adult patients demonstrated similar survival after a MRD vs 8 of 8 HLA-A, -B, -C, -DRB1 allele matched unrelated donors (MUD) vs 7 of 8 HLA MUD HCT.6 MDS patients differ in many ways from patients with de novo AML. Given the inherent differences in the disease biology of AML and MDS, it is imperative to define the features associated with outcome after HCT for MDS patients. With this aim, we conducted a disease-specific analysis using data reported to the Center for International Blood & Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) for patients with MDS.

Patients and methods

Data source

The CIBMTR is a combined research program of the Medical College of Wisconsin and the National Marrow Donor Program. The CIBMTR comprises a voluntary network of more than 450 transplantation centers worldwide that contribute detailed data on consecutive allogeneic and autologous HCT to a centralized statistical center. Observational studies conducted by the CIBMTR are performed in compliance with all applicable federal regulations pertaining to the protection of human research participants. Protected health information used in the performance of such research is collected and maintained in the CIBMTR capacity as a public health authority under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act Privacy Rule. Additional details regarding the data source are described elsewhere.7

Patient selection

The patient population consisted of adult patients (≥21 years) with MDS undergoing allogeneic HCT in the United States between 2002 and 2006, who had comprehensive data reported to the CIBMTR. A total of 701 cases fulfilling the inclusion criteria were identified. Of these, 176 received MRD transplants, 413 received 8 of 8 HLA-matched MUD transplants, and 112 received 7 of 8 HLA-matched MUD transplants. Patients whose grafts were depleted of T cells ex vivo were excluded. Patients undergoing umbilical cord blood transplantation and patients receiving stem cells from identical twins or HLA-mismatched or nonsibling-related donors were also excluded.

Due to missing data on IPSS components at HCT, we were unable to use IPSS to risk stratify patients at HCT. Therefore, to be able to define those with advanced disease status at HCT, we used bone marrow blasts percent (>5%) and a French American British [FAB8 ] class of refractory anemia with excess blasts, or refractory anemia with excess blasts in transformation, or chronic myelomonocytic leukemia at any time between diagnosis and HCT.

Study end points and definitions

The primary outcome studied was survival. Patients were considered to have an event at time of death from any cause; survivors were censored at last contact. Relapse was defined as disease recurrence as reported by the centers to the CIBMTR, and transplantation-related mortality (TRM) was considered a competing event. TRM was defined as death from any cause in the first 28 days post-HCT or death without evidence of disease recurrence beyond day 28. Disease-free survival (DFS) was defined as time to treatment failure (death or relapse). Time to engraftment was calculated as the time from transplantation to achieving the first of 3 consecutive days with an absolute neutrophil count >500/mm3. Acute graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) was graded using the International Blood & Marrow Transplant Research Severity Index.9 Chronic GVHD was diagnosed by standard criteria.10 For cumulative incidence of engraftment, death before engraftment was considered a competing event. Similarly, for cumulative incidence of GVHD, death without GVHD was considered a competing event.

Statistical analysis

All end points were assessed through 3 years from time of HCT with 91% follow-up data available to that time point. TRM, relapse, engraftment, acute GVHD, and chronic GVHD were estimated as cumulative incidences, taking into account competing risks. Probabilities of survival and DFS were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier estimator with variance estimated by the Greenwood formula. Survival curves were compared using the log-rank test. Multivariate analyses were conducted to identify and adjust for independent predictors of TRM, relapse, DFS, and survival other than donor type. The proportional hazards model was built by forcing the main effect variable (MRD vs 8 of 8 MUD vs 7 of 8 MUD, using MRD as the reference group) into the model. Backward elimination with a criterion of P < .05 for retention was used to select a final model. The following variables were analyzed for their prognostic value on each of the outcomes: patient characteristics (age, sex, race, and performance status [Karnofsky Performance scores]), disease characteristics (white blood cell count and IPSS score at diagnosis, therapy-related MDS, and disease status at transplantation), and transplant-related factors (interval between diagnosis and HCT, donor-recipient sex match, donor-recipient cytomegalovirus serostatus combinations, conditioning regimen intensity, stem cell source, GVHD prophylaxis regimen, and use of antithymocyte globulin). The proportional hazards assumption was assessed for each variable using a time-dependent covariate approach. Two-way interactions were checked between each selected variable and the main effect variable; no significant interactions were detected. Adjusted 3-year DFS and survival probabilities were estimated through the direct adjusted survival curves estimation method.11 SAS software, version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used in all analyses.

Results

Patients

Baseline characteristics of the population are summarized in Table 1. Median follow-up times for surviving patients were 50, 46, and 39 months for the MRD, 8 of 8 MUD, and 7 of 8 MUD donor groups, respectively. Median age (range) for the entire cohort was 53 years (22-78 years) and the distribution of age was similar among the 3 groups. The 7 of 8 MUD HCT recipients had a higher performance status at HCT compared with the other 2 groups. Most patients were white, but the MRD group had a higher proportion of non-white recipients. Two-thirds of the patients in each group had advanced disease at HCT. Most patients in all 3 groups had primary MDS. The distributions of IPSS categories and white blood cell count at diagnosis were similar among the 3 groups. Time between diagnosis and HCT was longest in the 7 of 8 MUD HCT recipients. As expected, donor age correlated with donor type. There was 3% of donors in the MRD group who were <30 years old, whereas 39% and 26% of donors in the 8 of 8 and 7 of 8 MUD groups, respectively, were <30 years old. There were more male donors in the 8 of 8 MUD HCT recipients, and both the 8 of 8 and 7 of 8 MUD HCT recipients were more likely than the MRD HCT recipients to be cytomegalovirus seronegative. There was 40% of patients in each of the 3 groups who received reduced intensity/nonmyeloablative conditioning regimens. MUD HCT recipients were more likely to receive marrow grafts, FK506-based GVHD prophylaxis, antithymocyte globulin therapy, and more recently undergo transplantation.

Baseline characteristics of 701 MDS patients that underwent allogeneic HCT between 2002 and 2006 and reported to the CIBMTR

| Variable . | MRD . | 8/8 MUD . | 7/8 MUD . | P* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 176 | 413 | 112 | |

| Age | 54 (22-72) | 53 (22-78) | 54 (26-72) | .19† |

| Age grouped | .06 | |||

| 20-29 | 6 (3) | 27 (7) | 3 (3) | |

| 30-39 | 16 (9) | 64 (15) | 8 (7) | |

| 40-49 | 45 (26) | 97 (23) | 36 (32) | |

| 50-59 | 79 (45) | 160 (39) | 46 (41) | |

| ≥60 | 30 (17) | 65 (16) | 19 (17) | |

| Gender | .07 | |||

| Male | 105 (60) | 245 (59) | 80 (71) | |

| Female | 70 (40) | 168 (41) | 32 (29) | |

| Missing | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | |

| Karnofsky score | <.001 | |||

| ≥90 | 101 (57) | 229 (55) | 72 (64) | |

| <90 | 68 (39) | 119 (29) | 30 (27) | |

| Missing | 7 (4) | 65 (16) | 10 (9) | |

| Race | .053 | |||

| White | 156 (89) | 392 (95) | 106 (95) | |

| Black | 8 (5) | 8 (2) | 1 (1) | |

| Asian | 8 (5) | 3 (1) | 2 (2) | |

| Others-American Indian-Native Hawaiian | 1 (1) | 2 (<1) | 1 (1) | |

| Missing | 3 (2) | 8 (2) | 2 (2) | |

| Bone marrow blast percent at transplant‡ | .41 | |||

| ≤5% | 76 (57) | 224 (63) | 62 (61) | |

| >5% | 57 (43) | 128 (36) | 40 (39) | |

| FAB at diagnosis§ | .31 | |||

| Refractory anemia | 47 (28) | 108 (26) | 25 (22) | |

| Refractory anemia with ringed sideroblasts | 10 (6) | 21 (5) | 8 (7) | |

| Refractory Anemia with Excess Blasts | 72 (43) | 154 (37) | 43 (39) | |

| Refractory anemia with excess blasts in transformation | 4 (2) | 15 (4) | 5 (4) | |

| Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia | 15 (9) | 42 (10) | 15 (13) | |

| MDS/MPD not otherwise specified | 18 (11) | 73 (17) | 15 (13) | |

| MDS disease status at transplant | .37 | |||

| Early | 58 (33) | 138 (33) | 33 (29) | |

| Advanced | 115 (65) | 264 (64) | 79 (71) | |

| Missing | 3 (2) | 11 (3) | 0 | |

| Secondary MDS (therapy related) | <.001 | |||

| No | 125 (71) | 329 (80) | 86 (77) | |

| Yes | 28 (16) | 81 (20) | 22 (20) | |

| Missing | 23 (13) | 3 (1) | 4 (4) | |

| Cytogenetics|| | .37 | |||

| Favorable (normal, ch. 5 abnormal, ch. 20 abnormal) | 79 (51) | 159 (47) | 46 (52) | |

| Adverse (≥3 abnormal, ch. 7 abnormal) | 39 (25) | 113 (33) | 27 (31) | |

| Intermediate (all others) | 37 (24) | 70 (20) | 15 (17) | |

| IPSS at diagnosis | .26 | |||

| Low | 19 (10) | 29 (7) | 12 (10) | |

| Int-1 | 37 (21) | 129 (31) | 27 (24) | |

| Int-2 | 41 (23) | 80 (19) | 21 (19) | |

| High | 9 (5) | 23 (5) | 8 (7) | |

| Missing | 70 (40) | 152 (37) | 44 (39) | |

| WBC at diagnosis | .82 | |||

| Less then 3.2 ×10^9/L | 85 (48) | 187 (45) | 51 (46) | |

| Greater than 3.2 ×10^9/L | 72 (41) | 189 (46) | 49 (44) | |

| Missing | 19 (11) | 37 (9) | 12 (11) | |

| Interval between diagnosis and transplant | 6 (2-129) | 8 (1-194) | 10 (2-269) | <.001† |

| Donor age | 52 (18-75) | 33 (19-60) | 36 (19-218) | <.001† |

| Donor age | <.001 | |||

| Younger than 20 y | 2 (1) | 8 (2) | 3 (3) | |

| 20-29 | 4 (2) | 151 (37) | 26 (23) | |

| 30-39 | 17 (10) | 141 (34) | 46 (41) | |

| 40-49 | 52 (30) | 92 (22) | 28 (25) | |

| 50-59 | 69 (39) | 20 (5) | 8 (7) | |

| Older than 60 y | 30 (17) | 1 (<1) | 0 | |

| Missing | 2 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | |

| Sex match | <.001 | |||

| M-M | 55 (31) | 196 (47) | 50 (45) | |

| M-F | 43 (25) | 110 (27) | 13 (12) | |

| F-M | 50 (29) | 49 (12) | 30 (27) | |

| F-F | 27 (15) | 58 (14) | 19 (17) | |

| Missing | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Cytomegalovirus match | <.001 | |||

| Pos-pos | 72 (41) | 65 (16) | 20 (18) | |

| Pos-neg | 16 (9) | 31 (8) | 15 (13) | |

| Neg-pos | 44 (25) | 151 (37) | 36 (32) | |

| Neg-neg | 34 (19) | 131 (32) | 34 (30) | |

| Not tested/inconclusive | 10 (6) | 35 (8) | 7 (6) | |

| Conditioning regimen intensity | <.001 | |||

| Myeloablative | 99 (56) | 246 (59) | 65 (58) | |

| Reduced intensity | 46 (26) | 119 (29) | 33 (29) | |

| Nonmyeloblative | 24 (15) | 47 (11) | 14 (13) | |

| Missing | 4 (2) | 1 (<1) | 0 | |

| Stem cell source | <.001 | |||

| Bone marrow | 14 (8) | 123 (30) | 21 (19) | |

| Peripheral blood | 162 (92) | 290 (70) | 91 (81) | |

| GVHD prophylaxis | <.001 | |||

| None | 1 (1) | 1 (<1) | 1 (1) | |

| FK506+MTX+-oth | 57 (32) | 198 (48) | 45 (40) | |

| FK506+-oth | 30 (17) | 63 (15) | 28 (25) | |

| CsA+MTX+-oth | 40 (23) | 91 (22) | 26 (23) | |

| CsA+-oth | 46 (26) | 50 (12) | 11 (10) | |

| Other | 2 (1) | 10 (2) | 1 (1) | |

| Anti-thymocyte globulin therapy | <.001 | |||

| No | 158 (90) | 306 (74) | 82 (73) | |

| Yes | 18 (10) | 107 (26) | 30 (27) | |

| Year of transplant | .01 | |||

| 2002 | 38 (22) | 47 (11) | 14 (13) | |

| 2003 | 23 (13) | 69 (17) | 22 (20) | |

| 2004 | 37 (21) | 81 (20) | 19 (17) | |

| 2005 | 44 (25) | 91 (22) | 32 (29) | |

| 2006 | 34 (19) | 125 (30) | 25 (22) | |

| Median (range) follow-up of survivors, mo | 50 (3-96) | 46 (6-87) | 39 (9-83) | |

| Total number died | 107 | 253 | 82 |

| Variable . | MRD . | 8/8 MUD . | 7/8 MUD . | P* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 176 | 413 | 112 | |

| Age | 54 (22-72) | 53 (22-78) | 54 (26-72) | .19† |

| Age grouped | .06 | |||

| 20-29 | 6 (3) | 27 (7) | 3 (3) | |

| 30-39 | 16 (9) | 64 (15) | 8 (7) | |

| 40-49 | 45 (26) | 97 (23) | 36 (32) | |

| 50-59 | 79 (45) | 160 (39) | 46 (41) | |

| ≥60 | 30 (17) | 65 (16) | 19 (17) | |

| Gender | .07 | |||

| Male | 105 (60) | 245 (59) | 80 (71) | |

| Female | 70 (40) | 168 (41) | 32 (29) | |

| Missing | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | |

| Karnofsky score | <.001 | |||

| ≥90 | 101 (57) | 229 (55) | 72 (64) | |

| <90 | 68 (39) | 119 (29) | 30 (27) | |

| Missing | 7 (4) | 65 (16) | 10 (9) | |

| Race | .053 | |||

| White | 156 (89) | 392 (95) | 106 (95) | |

| Black | 8 (5) | 8 (2) | 1 (1) | |

| Asian | 8 (5) | 3 (1) | 2 (2) | |

| Others-American Indian-Native Hawaiian | 1 (1) | 2 (<1) | 1 (1) | |

| Missing | 3 (2) | 8 (2) | 2 (2) | |

| Bone marrow blast percent at transplant‡ | .41 | |||

| ≤5% | 76 (57) | 224 (63) | 62 (61) | |

| >5% | 57 (43) | 128 (36) | 40 (39) | |

| FAB at diagnosis§ | .31 | |||

| Refractory anemia | 47 (28) | 108 (26) | 25 (22) | |

| Refractory anemia with ringed sideroblasts | 10 (6) | 21 (5) | 8 (7) | |

| Refractory Anemia with Excess Blasts | 72 (43) | 154 (37) | 43 (39) | |

| Refractory anemia with excess blasts in transformation | 4 (2) | 15 (4) | 5 (4) | |

| Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia | 15 (9) | 42 (10) | 15 (13) | |

| MDS/MPD not otherwise specified | 18 (11) | 73 (17) | 15 (13) | |

| MDS disease status at transplant | .37 | |||

| Early | 58 (33) | 138 (33) | 33 (29) | |

| Advanced | 115 (65) | 264 (64) | 79 (71) | |

| Missing | 3 (2) | 11 (3) | 0 | |

| Secondary MDS (therapy related) | <.001 | |||

| No | 125 (71) | 329 (80) | 86 (77) | |

| Yes | 28 (16) | 81 (20) | 22 (20) | |

| Missing | 23 (13) | 3 (1) | 4 (4) | |

| Cytogenetics|| | .37 | |||

| Favorable (normal, ch. 5 abnormal, ch. 20 abnormal) | 79 (51) | 159 (47) | 46 (52) | |

| Adverse (≥3 abnormal, ch. 7 abnormal) | 39 (25) | 113 (33) | 27 (31) | |

| Intermediate (all others) | 37 (24) | 70 (20) | 15 (17) | |

| IPSS at diagnosis | .26 | |||

| Low | 19 (10) | 29 (7) | 12 (10) | |

| Int-1 | 37 (21) | 129 (31) | 27 (24) | |

| Int-2 | 41 (23) | 80 (19) | 21 (19) | |

| High | 9 (5) | 23 (5) | 8 (7) | |

| Missing | 70 (40) | 152 (37) | 44 (39) | |

| WBC at diagnosis | .82 | |||

| Less then 3.2 ×10^9/L | 85 (48) | 187 (45) | 51 (46) | |

| Greater than 3.2 ×10^9/L | 72 (41) | 189 (46) | 49 (44) | |

| Missing | 19 (11) | 37 (9) | 12 (11) | |

| Interval between diagnosis and transplant | 6 (2-129) | 8 (1-194) | 10 (2-269) | <.001† |

| Donor age | 52 (18-75) | 33 (19-60) | 36 (19-218) | <.001† |

| Donor age | <.001 | |||

| Younger than 20 y | 2 (1) | 8 (2) | 3 (3) | |

| 20-29 | 4 (2) | 151 (37) | 26 (23) | |

| 30-39 | 17 (10) | 141 (34) | 46 (41) | |

| 40-49 | 52 (30) | 92 (22) | 28 (25) | |

| 50-59 | 69 (39) | 20 (5) | 8 (7) | |

| Older than 60 y | 30 (17) | 1 (<1) | 0 | |

| Missing | 2 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | |

| Sex match | <.001 | |||

| M-M | 55 (31) | 196 (47) | 50 (45) | |

| M-F | 43 (25) | 110 (27) | 13 (12) | |

| F-M | 50 (29) | 49 (12) | 30 (27) | |

| F-F | 27 (15) | 58 (14) | 19 (17) | |

| Missing | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Cytomegalovirus match | <.001 | |||

| Pos-pos | 72 (41) | 65 (16) | 20 (18) | |

| Pos-neg | 16 (9) | 31 (8) | 15 (13) | |

| Neg-pos | 44 (25) | 151 (37) | 36 (32) | |

| Neg-neg | 34 (19) | 131 (32) | 34 (30) | |

| Not tested/inconclusive | 10 (6) | 35 (8) | 7 (6) | |

| Conditioning regimen intensity | <.001 | |||

| Myeloablative | 99 (56) | 246 (59) | 65 (58) | |

| Reduced intensity | 46 (26) | 119 (29) | 33 (29) | |

| Nonmyeloblative | 24 (15) | 47 (11) | 14 (13) | |

| Missing | 4 (2) | 1 (<1) | 0 | |

| Stem cell source | <.001 | |||

| Bone marrow | 14 (8) | 123 (30) | 21 (19) | |

| Peripheral blood | 162 (92) | 290 (70) | 91 (81) | |

| GVHD prophylaxis | <.001 | |||

| None | 1 (1) | 1 (<1) | 1 (1) | |

| FK506+MTX+-oth | 57 (32) | 198 (48) | 45 (40) | |

| FK506+-oth | 30 (17) | 63 (15) | 28 (25) | |

| CsA+MTX+-oth | 40 (23) | 91 (22) | 26 (23) | |

| CsA+-oth | 46 (26) | 50 (12) | 11 (10) | |

| Other | 2 (1) | 10 (2) | 1 (1) | |

| Anti-thymocyte globulin therapy | <.001 | |||

| No | 158 (90) | 306 (74) | 82 (73) | |

| Yes | 18 (10) | 107 (26) | 30 (27) | |

| Year of transplant | .01 | |||

| 2002 | 38 (22) | 47 (11) | 14 (13) | |

| 2003 | 23 (13) | 69 (17) | 22 (20) | |

| 2004 | 37 (21) | 81 (20) | 19 (17) | |

| 2005 | 44 (25) | 91 (22) | 32 (29) | |

| 2006 | 34 (19) | 125 (30) | 25 (22) | |

| Median (range) follow-up of survivors, mo | 50 (3-96) | 46 (6-87) | 39 (9-83) | |

| Total number died | 107 | 253 | 82 |

ch., chromosome; CsA, cyclosporin; F, female; FK506, tacrolimus; M, male; MTX, methotrexate; neg, negative; oth, other; pos, positive.

χ-square test.

Wilcoxon scores test.

Missing = 114.

In 80% of patients, the FAB class did not change from diagnosis to transplant, and in 9%, the FAB progressed to an advanced category.

Missing = 116.

GVHD and engraftment

By day 100 post-HCT, the cumulative incidence of neutrophil recovery was ≥90% in all 3 groups (P = .09) (Table 2). Similarly, by day 100 the cumulative incidence of platelet recovery was not significantly different among the 3 groups (77% to 86%; P = .24) (Table 2). By day 100, the cumulative incidence of grades B to D (P = .009) and grades C to D (P = .024) acute GVHD was significantly higher in recipients of unrelated donor transplantation than MRD transplantation (Table 2). By 3 years posttransplantation, the cumulative incidence of chronic GVHD did not differ significantly among the 3 groups (41% to 51%; P = .25) (Table 2).

Univariate analysis of engraftment, acute and chronic GVHD, DFS and Survival in 701 MDS patients that underwent allogeneic HCT from 2002-2006 by donor type

| . | MRD . | 8/8 MUD . | 7/8 MUD . | . | 8/8 MUD vs MRD . | 7/8 MUD vs MRD . | 7/8 MUD vs 8/8 MUD . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome . | N . | Probability (95% CI) . | N . | Probability (95% CI) . | N . | Probability (95% CI) . | P* . | P‡ . | P‡ . | P‡ . |

| ANC recovery | 176 | 413 | 112 | |||||||

| @ 28 d | 93 (89-96) | 92 (89-95) | 87 (79-92) | .21 | ||||||

| @ 100 d | 96 (93-99) | 96 (94-98) | 90 (84-95) | .09 | ||||||

| Platelets recovery (20 × 109/L) | 174 | 413 | 111 | |||||||

| @ 60 d | 86 (80-90) | 80 (75-83) | 76 (67-83) | .08 | ||||||

| @ 100 d | 86 (80-90) | 83 (79-86) | 77 (69-85) | .24 | ||||||

| Acute GVHD grade B-D | 176 | 413 | 111 | |||||||

| @ 100 d | 42 (35-49) | 54 (49-59) | 57 (48-67) | .009 | .006 | .009 | .52 | |||

| Acute GVHD grade C-D | 176 | 413 | 112 | |||||||

| @ 100 d | 21 (15-27) | 31 (27-36) | 30 (22-39) | .024 | .007 | .08 | .85 | |||

| Chronic GVHD | 171 | 400 | 110 | |||||||

| @ 1 y | 45 (38-53) | 47 (42-52) | 34 (25-43) | .033 | .66 | .055 | .009 | |||

| @ 3 y | 51 (43-59) | 49 (45-55) | 41 (32-51) | .25 | ||||||

| TRM | 175 | 413 | 112 | |||||||

| @ 1 y | 25 (18-31) | 32 (28-37) | 37 (28-46) | .06 | ||||||

| @ 3 y | 32 (25-39) | 40 (35-44) | 44 (34-53) | .08 | ||||||

| Relapse | 175 | 413 | 112 | |||||||

| @ 1 y | 25 (19-32) | 22 (19-27) | 24 (17-32) | .78 | ||||||

| @ 3 y | 30 (23-37) | 25 (21-29) | 28 (20-37) | .41 | ||||||

| DFS | 175 | 413 | 112 | .06† | ||||||

| @ 1 y | 50 (42-57) | 45 (40-50) | 40 (31-49) | .24* | ||||||

| @ 3 y | 38 (30-45) | 35 (30-40) | 28 (20-37) | .21* | ||||||

| Survival | 176 | 413 | 112 | .01† | ||||||

| @ 1 y | 57 (49-64) | 53 (48-58) | 46 (37-55) | .19* | ||||||

| @ 3 y | 44 (37-52) | 39 (34-44) | 29 (21-39) | .03* | .27 | .01 | .05 | |||

| . | MRD . | 8/8 MUD . | 7/8 MUD . | . | 8/8 MUD vs MRD . | 7/8 MUD vs MRD . | 7/8 MUD vs 8/8 MUD . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome . | N . | Probability (95% CI) . | N . | Probability (95% CI) . | N . | Probability (95% CI) . | P* . | P‡ . | P‡ . | P‡ . |

| ANC recovery | 176 | 413 | 112 | |||||||

| @ 28 d | 93 (89-96) | 92 (89-95) | 87 (79-92) | .21 | ||||||

| @ 100 d | 96 (93-99) | 96 (94-98) | 90 (84-95) | .09 | ||||||

| Platelets recovery (20 × 109/L) | 174 | 413 | 111 | |||||||

| @ 60 d | 86 (80-90) | 80 (75-83) | 76 (67-83) | .08 | ||||||

| @ 100 d | 86 (80-90) | 83 (79-86) | 77 (69-85) | .24 | ||||||

| Acute GVHD grade B-D | 176 | 413 | 111 | |||||||

| @ 100 d | 42 (35-49) | 54 (49-59) | 57 (48-67) | .009 | .006 | .009 | .52 | |||

| Acute GVHD grade C-D | 176 | 413 | 112 | |||||||

| @ 100 d | 21 (15-27) | 31 (27-36) | 30 (22-39) | .024 | .007 | .08 | .85 | |||

| Chronic GVHD | 171 | 400 | 110 | |||||||

| @ 1 y | 45 (38-53) | 47 (42-52) | 34 (25-43) | .033 | .66 | .055 | .009 | |||

| @ 3 y | 51 (43-59) | 49 (45-55) | 41 (32-51) | .25 | ||||||

| TRM | 175 | 413 | 112 | |||||||

| @ 1 y | 25 (18-31) | 32 (28-37) | 37 (28-46) | .06 | ||||||

| @ 3 y | 32 (25-39) | 40 (35-44) | 44 (34-53) | .08 | ||||||

| Relapse | 175 | 413 | 112 | |||||||

| @ 1 y | 25 (19-32) | 22 (19-27) | 24 (17-32) | .78 | ||||||

| @ 3 y | 30 (23-37) | 25 (21-29) | 28 (20-37) | .41 | ||||||

| DFS | 175 | 413 | 112 | .06† | ||||||

| @ 1 y | 50 (42-57) | 45 (40-50) | 40 (31-49) | .24* | ||||||

| @ 3 y | 38 (30-45) | 35 (30-40) | 28 (20-37) | .21* | ||||||

| Survival | 176 | 413 | 112 | .01† | ||||||

| @ 1 y | 57 (49-64) | 53 (48-58) | 46 (37-55) | .19* | ||||||

| @ 3 y | 44 (37-52) | 39 (34-44) | 29 (21-39) | .03* | .27 | .01 | .05 | |||

ANC, absolute neutrophil count.

Overall pointwise.

Log-rank.

Pointwise pairwise comparison.

Transplant-related mortality

In univariate analysis, the cumulative incidence of TRM at 1 (P = .06) and 3 years (P = .08) were not significantly higher in both unrelated groups compared with the MRD HCT recipients (Table 2). In multivariate analysis, the risk of TRM was higher in 8 of 8 MUD HCT recipients (relative risk [RR] 1.44 [95% CI 1.06-1.95]), and in 7 of 8 MUD HCT recipients (RR 1.80 [95% CI 1.23-2.63]) compared with the MRD HCT recipients. TRM risk was higher, but not statistically significant, in the 7 of 8 MUD compared with the 8 of 8 MUD HCT recipients (RR 1.25 [95% CI 0.91-1.72]) (Table 3; Figure 1). Other adverse prognostic factors that were significant in the final TRM model included female donor/male recipient and lower KPS at transplant.

Multivariate analysis for TRM, relapse, treatment failure, and mortality in adult MDS patients who underwent HLA-identical sibling (MRD) HCT or 8/8 or 7/8 MUD HCT from 2002-2006

| . | TRM* . | P . | Relapse† . | P . | Treatment failure (death or relapse)‡ . | P . | Mortality§ . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR (95% CI) . | RR (95% CI) . | RR (95% CI) . | RR (95% CI) . | |||||

| 8/8 MUD vs MRD | 1.43 (1.06-1.95) | .02 | 0.85 (0.60-1.18) | .33 | 1.13 (0.91-1.42) | .26 | 1.24 (0.98-1.56) | .06 |

| 7/8 MUD vs MRD | 1.80 (1.23-2.63) | .002 | 1.02 (0.66-1.60) | .91 | 1.47 (1.10-1.96) | .008 | 1.62 (1.21-2.17) | .001 |

| 7/8 MUD vs 8/8 MUD | 1.25 (0.91-1.72) | .16 | 1.21 (0.81-1.81) | .35 | 1.29 (1.00-1.66) | .04 | 1.30 (1.01-1.68) | .03 |

| . | TRM* . | P . | Relapse† . | P . | Treatment failure (death or relapse)‡ . | P . | Mortality§ . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR (95% CI) . | RR (95% CI) . | RR (95% CI) . | RR (95% CI) . | |||||

| 8/8 MUD vs MRD | 1.43 (1.06-1.95) | .02 | 0.85 (0.60-1.18) | .33 | 1.13 (0.91-1.42) | .26 | 1.24 (0.98-1.56) | .06 |

| 7/8 MUD vs MRD | 1.80 (1.23-2.63) | .002 | 1.02 (0.66-1.60) | .91 | 1.47 (1.10-1.96) | .008 | 1.62 (1.21-2.17) | .001 |

| 7/8 MUD vs 8/8 MUD | 1.25 (0.91-1.72) | .16 | 1.21 (0.81-1.81) | .35 | 1.29 (1.00-1.66) | .04 | 1.30 (1.01-1.68) | .03 |

Other significant factors in the multivariate model includes the following:

KPS and female donor into male recipient.

Disease status at HCT, IPSS at diagnosis, and conditioning regimen.

KPS and IPSS at diagnosis.

Age, KPS, and IPSS at diagnosis.

Adjusted probability of transplant-related mortality in adult MDS patients by donor source. In multivariate analysis, the risk of transplant-related mortality was lower in MRD HCT recipients compared with both MUD groups (RR 1.44 (95% CI 1.06-1.95) and 1.80 (95% CI 1.23-2.63) for 8/8 MUD and 7/8 MUD HCT recipients, respectively).

Adjusted probability of transplant-related mortality in adult MDS patients by donor source. In multivariate analysis, the risk of transplant-related mortality was lower in MRD HCT recipients compared with both MUD groups (RR 1.44 (95% CI 1.06-1.95) and 1.80 (95% CI 1.23-2.63) for 8/8 MUD and 7/8 MUD HCT recipients, respectively).

The 3-year probabilities of TRM, adjusted for other significant variables in the multivariate models were 29% (95% CI 22-35), 41% (95% CI 36-46), and 42% (95% CI 33-51) after MRD, 8 of 8 MUD, and 7 of 8 MUD transplantation, respectively (Table 4).

Adjusted 3-year cumulative incidences of TRM, relapse, and 3-year probabilities of DFS and survival in adult patients with primary and secondary MDS who underwent HLA-identical sibling (MRD) HCT or 8/8 or 7/8 MUD HCT from 2002-2006

| . | MRD Probability (95% CI) . | 8/8 MUD Probability (95% CI) . | 7/8 MUD Probability (95% CI) . | 8/8 MUD vs MRD . | 7/8 MUD vs MRD . | 7/8 MUD vs 8/8 MUD . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P* . | P* . | P* . | ||||

| TRM | 29 (22-35) | 41 (36-46) | 42 (33-51) | .003 | .01 | .74 |

| Relapse | 31 (24-38) | 25 (21-29) | 27 (20-35) | .11 | .46 | .57 |

| DFS | 41 (34-48) | 35 (30-40) | 29 (21-37) | .16 | .02 | .19 |

| Survival | 47 (40-55) | 38 (34-43) | 31 (22-39) | .04 | .003 | .11 |

| . | MRD Probability (95% CI) . | 8/8 MUD Probability (95% CI) . | 7/8 MUD Probability (95% CI) . | 8/8 MUD vs MRD . | 7/8 MUD vs MRD . | 7/8 MUD vs 8/8 MUD . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P* . | P* . | P* . | ||||

| TRM | 29 (22-35) | 41 (36-46) | 42 (33-51) | .003 | .01 | .74 |

| Relapse | 31 (24-38) | 25 (21-29) | 27 (20-35) | .11 | .46 | .57 |

| DFS | 41 (34-48) | 35 (30-40) | 29 (21-37) | .16 | .02 | .19 |

| Survival | 47 (40-55) | 38 (34-43) | 31 (22-39) | .04 | .003 | .11 |

Pointwise pairwise comparison.

Relapse

In univariate analysis, the 1-year (P = .78) and 3-year (P = .41) cumulative incidences of relapse were similar among the 3 groups (Table 2). There was no difference in the risk of relapse between the groups in the multivariate analysis (overall P value = .49) (Table 3; Figure 2). Other predictive factors that were significant in the final relapse model included higher IPSS score at diagnosis, advanced disease status at transplant, and lower conditioning regimen intensity.

Adjusted probability of relapse in adult MDS patients by donor source. In multivariate analysis there was no difference in the risk of relapse among the three groups.

Adjusted probability of relapse in adult MDS patients by donor source. In multivariate analysis there was no difference in the risk of relapse among the three groups.

The 3-year probabilities of relapse, adjusted for other significant variables in the multivariate models, were 31% (95% CI 24-38), 25% (95% CI 21-29), and 27% (95% CI 20-35) after MRD, 8 of 8 MUD, and 7 of 8 MUD transplantation, respectively (Table 4).

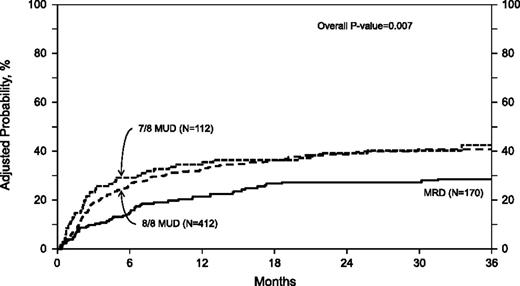

DFS

In univariate analysis, the 1-year (P = .24) and 3-year (P = .21) probabilities of DFS were not significantly different among the 3 groups (Table 2). In multivariate analysis, the risk of treatment failure (death or relapse, inverse of DFS) was similar with 8 of 8 MUD transplantation (RR 1.13 [95% CI 0.91-1.42]), but higher with 7 of 8 MUD transplantation (RR 1.47 [95% CI 1.10-1.96]) when compared with MRD transplantation (Table 3; Figure 3). There was 7 of 8 MUD HCT that was also associated with higher risk of treatment failure when compared with 8 of 8 MUD HCT (RR 1.29 [95% CI 1.00-1.66]). Other negative prognostic factors that were significant in the final DFS model included lower KPS and higher IPSS score at diagnosis.

Adjusted probability of DFS in 694 adult MDS patients by donor source. In multivariate analysis, the risk of treatment failure (death or relapse) was significantly higher with 7 of 8 MUD HCT recipients compared with MRD and 8 of 8 MUD HCT recipients (RR 1.47 [95% CI 1.10-1.96] and 1.29 [95% CI 1.00-1.66], respectively). The risk was not different between 8 of 8 MUD and MRD HCT recipients (RR 1.13, 95% CI 0.91-1.42).

Adjusted probability of DFS in 694 adult MDS patients by donor source. In multivariate analysis, the risk of treatment failure (death or relapse) was significantly higher with 7 of 8 MUD HCT recipients compared with MRD and 8 of 8 MUD HCT recipients (RR 1.47 [95% CI 1.10-1.96] and 1.29 [95% CI 1.00-1.66], respectively). The risk was not different between 8 of 8 MUD and MRD HCT recipients (RR 1.13, 95% CI 0.91-1.42).

The 3-year probabilities of DFS, adjusted for other significant variables in the multivariate models, were 41% (95% CI 34-48), 35% (95% CI 30-40), and 29% (95% CI 21-37) after MRD, 8 of 8 MUD, and 7 of 8 MUD transplantation, respectively (Table 4).

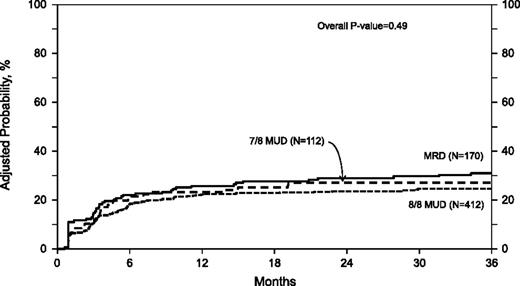

Survival

In univariate analysis, compared with the MRD group, the 3-year probability of survival was similar in the 8 of 8 MUD HCT recipients (P = .27), but lower in the 7 of 8 MUD group (P = .01). The 3-year survival was lower in the 7 of 8 MUD group compared with the 8 of 8 MUD group (P = .05) (Table 2). In multivariate analysis, survival was similar after 8 of 8 MUD transplantation compared with MRD transplantation (all-cause mortality RR 1.24 [95% CI 0.98-1.56]). Survival was significantly lower after 7 of 8 MUD HCT compared with MRD HCT (all-cause mortality RR 1.62 [95% CI 1.21-2.17]) and compared with 8 of 8 MUD HCT (all-cause mortality RR 1.30 [95% CI 1.01-1.68]) (Table 3; Figure 4). Other adverse covariates that were significant in the final survival model included older age, lower KPS, and higher IPSS score at diagnosis.

Adjusted probability of overall survival in 701 adult MDS patients by donor source. In multivariate analysis, the risk of all-cause mortality was significantly higher with 7 of 8 MUD HCT recipients compared with MRD and 8 of 8 MUD HCT recipients (RR 1.62 [95% CI 1.21-2.17] and 1.30 [95% CI 1.01-1.68], respectively). The risk was not different between 8 of 8 MUD and MRD HCT recipients (RR 1.24, 95% CI 0.98-1.56).

Adjusted probability of overall survival in 701 adult MDS patients by donor source. In multivariate analysis, the risk of all-cause mortality was significantly higher with 7 of 8 MUD HCT recipients compared with MRD and 8 of 8 MUD HCT recipients (RR 1.62 [95% CI 1.21-2.17] and 1.30 [95% CI 1.01-1.68], respectively). The risk was not different between 8 of 8 MUD and MRD HCT recipients (RR 1.24, 95% CI 0.98-1.56).

The 3-year probabilities of survival, adjusted for other significant variables in the multivariate models, were 47% (95% CI 40-55), 38% (95% CI 34-43), and 31% (95% CI 22-39) after MRD, 8 of 8 MUD, and 7 of 8 MUD transplantation, respectively (Table 4).

Primary MDS

A subgroup analysis of outcomes restricted to patients with primary MDS (n = 540) was conducted. In multivariate analysis, relapse risk was similar among the 3 groups (overall P = .33), but TRM risk was higher in both unrelated donor groups compared with the MRD group (RR 1.46 [95% CI 1.02-2.06] and 1.76 [95% CI 1.14-2.70] for 8 of 8 MUD and 7 of 8 MUD groups, respectively). Treatment failure risk was similar in the 8 of 8 MUD group (RR 1.11 [95% CI 0.86-1.44]) and not significantly higher in the 7 of 8 MUD group (RR 1.39[ 95% CI 0.99-1.93]) compared with the MRD group. Survival probabilities were significantly lower after both 8 of 8 and 7 of 8 unrelated donor HCT compared with the MRD HCT (RR 1.32 [95% CI 1.00-1.73] and 1.60 [95% CI 1.13-2.27] for 8 of 8 MUD and 7 of 8 MUD groups, respectively).

The 3-year adjusted probabilities for relapse, TRM, DFS, and survival are summarized in supplemental Table 1 (available on the Blood Web site).

Causes of death

Supplemental Table 2 summarizes the causes of death by donor type as reported by the transplant centers. The most common cause of death in all groups was relapse of primary disease (35%, 28%, and 28% in MRD, 8 of 8 MUD, and 7 of 8 MUD groups, respectively). Graft rejection and organ toxicity are reported as causes of death in both MUD groups, but were rare in the MRD group (supplemental Table 2).

Discussion

For patients with MDS, despite the improvement in survival with the introduction of hypomethylating agents,12,13 allo-HCT remains the only potentially curative therapy. Significant advances involving all aspects of transplantation have been achieved over the past 2 decades.14-17 As a result of this progress, the numbers of allo-HCTs performed on an annual basis in the United States have steadily increased, and robust improvement in post-HCT outcomes have been observed in patients of all ages and across different malignancies.18,19 For patients with MDS, outcomes have improved after both MRD HCT,19 as well as after MUD.20

Although these data are reassuring, there are no prospective clinical trials comparing HCT to non-HCT therapies, and there are many unanswered questions that remain regarding the exact role of HCT for patients with MDS.21 Previous studies comparing MRD and MUD transplantation have yielded conflicting results, with some reporting inferior survival or DFS with MUD HCTs,22,23 and others reporting similar survival.24,25

A prior CIBMTR analysis in 2 223 adults with AML demonstrated similar survival among MRD HCT, 8 of 8 MUD HCT, and 7 of 8 MUD HCT recipients.6 The risk of relapse was lower after 7 of 8 MUD and similar after 8 of 8 MUD HCT, compared with MRD HCT. We also observed higher TRM risk after 7 of 8 MUD, but not after 8 of 8 MUD compared with MRD.6 In this study among patients with MDS, we observed an increased risk of TRM with both MUD groups, but no reduction in relapse risk.

In a recent study, Walter et al26 compared the frequency of recurrently mutated genes in de novo MDS and AML. Mutations involving TP53, U2AF1, SF3B1, NF1, EZH2, and BCOR were detected at a significantly higher rate among MDS cases compared with AML. Conversely, mutations involving FLT3, NPM1, IDH1, and IDH2 were detected at higher rates among AML cases.26 These findings strongly suggest that important differences in pathophysiology exist between MDS and AML, and that these differences may also influence outcomes after HCT. Additionally, MDS patients are often not in complete remission at the time of HCT. This additional disease burden may reduce the efficacy of graft vs MDS effects. In our previous AML analysis, 70%, 68%, and 64% of MRD, 8 of 8 MUD, and 7 of 8 MUD HCT recipients were in complete remission at the time of HCT, respectively.6 In the current analysis, two-thirds of the entire cohort had advanced disease by FAB and bone marrow blasts percent at transplant. Scott et al27 examined whether the use of induction chemotherapy (IC) prior to conditioning improves post HCT outcomes among a cohort of 125 patients, all of whom had advanced MDS by FAB. Only 33 patients received IC. The use of IC was not associated with any improvement in outcomes. However, a fairly small sample size that prohibited a full multivariate analysis, was an important limitation. In addition, all of these patients were transplanted in the era before hypomethylating agents were widely available.27 Therefore, we believe the differences in molecular pathology and disease burden at the time of transplant between patients with MDS and AML largely explain the discrepancy in outcomes between patients transplanted with well-matched compared with partially matched donors. To be able to dissect the impact of patient-related and disease-related factors from transplant-related factors on outcomes, the selection criteria used in the current analysis is identical to the criteria that were used to select the AML cohort.6

Furthermore, MDS patients are generally older and may have higher burden of comorbidities. Data on the Hematopoietic Cell Transplant-Comorbidity Index was not collected on patients enrolled in the current analysis.28 A higher Hematopoietic Cell Transplant-Comorbidity Index potentially could be responsible for higher TRM, not only after 7 of 8 MUD, but also after 8 of 8 MUD compared with MRD HCT.

In multivariate analysis of the entire cohort, survival, and DFS rates were similar after 8 of 8 MUD HCT compared with MRD HCT, but were significantly lower after 7 of 8 MUD HCT. Excess TRM with no disease control advantage accounted for worse outcomes with 7 of 8 MUD HCT. Time from diagnosis to HCT was longest in the 7 of 8 MUD group, and although this variable was adjusted for in the multivariate analysis, the decision to pursue transplantation with these less than optimal donors was likely undertaken later in the disease course, and this can possibly explain the inferior outcomes among the 7 of 8 MUD HCT recipients. In a subgroup analysis of outcomes of patients with primary MDS, DFS rates were similar after 8 of 8 MUD HCT compared with MRD HCT, and lower after 7 of 8 MUD HCT. However, in this subgroup analysis, survival was also significantly lower not only after 7 of 8 MUD HCT, but also after 8 of 8 MUD HCT compared with MRD HCT. The pattern of failure was again driven by excess in TRM after unrelated donor HCT.

Higher rates of acute GVHD grades B to D and C to D were seen in the MUD groups compared with the MRD group. This increase rate of acute GVHD likely contributed to the observed higher TRM in the MUD groups compared with the MRD group.

In multivariate analysis the risk of relapse was similar among the 3 groups. However, there was no difference seen in chronic GVHD at 3 years, and because with previous work it was suggested that the development of chronic (but not acute) GVHD is associated with lower relapse rate,29 this may, in part, explain the lack of protection against the relapse that would be expected with MUD HCT compared with MRD HCT.

To identify the optimal role of HCT for Medicare beneficiaries with MDS, an ongoing CIBMTR study will compare the 100-day survival of 240 MDS patients age ≥65 years that underwent HCT to a similar cohort age 55 to 64 years, to determine if HCT is associated with excessive early mortality in older patients. Interim analyses have not exceeded the stopping rule threshold.30 This study continues to accrue patients and will also examine prognostic factors in older patients. However, given the advances in non-HCT therapies, a prospective comparative trial is needed to determine whether HCT is associated with survival advantage in older MDS patients. To address this question, a phase 2 biologic randomization trial of 230 patients aged 55 to 70 years is currently ongoing in Europe.31 Furthermore, a US biologic randomization trial of donor vs no donor therapies in >400 patients with IPSS intermediate-2 or high-risk disease, aged 50 to 75 years, is expected to begin enrollment in 2013. Both the European and the US trials are poised to address not only survival questions, but also quality of life and costs of care associated with the 2 treatment strategies.

To our knowledge, this is the first disease-specific analysis that compares these 3 donor sources in a large cohort of recently treated MDS patients. Many comparative analyses of different donor sources include patients with different hematologic malignancies together in multivariate analyses.29,32,33 These analyses were adjusted for disease type, and although this approach has the advantage of increasing the sample size, differential effects of donor source on specific malignancies may require an even larger sample and an interaction test could be limited by a type II error. This is especially true if the model is already adjusting for many other covariates.

In an analysis of 719 MDS patients (median age 58 years), the impact of donor age on post-HCT outcomes was analyzed. In this study, the median donor ages of related donors and unrelated donors were 56 years (range 35-78 years) and 34 years (range 19-64 years), respectively. In multivariate analysis, HCT from the younger unrelated donors (<30 years of age) was associated with superior survival compared with HCT from the older related donors (RR 0.65 [95% CI 0.45-0.95]).34 However, in a recent analysis of 2172 patients with leukemia and lymphoma, Alousi et al35 compared outcomes after an HCT from younger unrelated donor (donor age <50 years; n = 757) to HCT from an older MRD (donor age = 50 years; n = 1 415). In multivariate analysis, HCT from an older MRD was associated with superior outcomes compared with HCT from a younger unrelated donor. A strong correlation between donor age and donor source in our dataset limited our ability to examine the independent association between donor age and post-HCT outcomes.

Our analysis has limitations that are expected in a registry-based study. Data on important prognostic factors, such as iron overload36,37 and comorbidities38-41 were not available for these patients. Additionally, detailed data on pre-HCT therapies and disease response to different lines of treatments were not available. Due to missing data on some its components, we were unable to compute IPSS scores “at HCT” to risk stratify patients. Importantly, none of the widely used risk stratification systems are “transplant-specific,” because all of these prognostic systems included only a minority of patients that underwent HCT, and these few patients were censored at the time of HCT.2,3,42-44 In addition, only 2 of these systems are time-dependent.43,44 Furthermore, in a previous paper by Sierra et al,45 analyzing post-MRD HCT outcomes among MDS patients, multivariate analysis adjusting for IPSS scores at diagnosis and at transplant, FAB subtypes and blasts percent, it was found that only blasts percent at transplant was associated with DFS and overall survival. After adjusting for IPSS scores “at diagnosis” in all of our analyses, we used the reported pre-transplant bone marrow blasts percent and the FAB classification to assign patients into early vs advanced disease status, data readily available in the registry.

Future comparative studies of donor source should incorporate emerging prognostic factors, examine the prognostic value of recently identified novel mutations,26,46,47 further evaluate the role of pre-transplantation cytoreductive strategies,27,48 and continue to investigate strategies to prevent relapse post HCT.49,50

In conclusion, our study confirms that for patients with MDS, although significant progress has been achieved in unrelated donor HCT, donor source remains a critical determinant of outcomes. An HLA-matched sibling remains the best donor source followed by 8 of 8 MUD HCT. Transplantation from a 7 of 8 MUD is associated with inferior outcomes. These results should inform clinicians, patients, and the design of prospective clinical trials.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work (CIBMTR) was supported by the Public Health Service Grant/Cooperative Agreement U24-CA76518 from the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, a Grant/Cooperative Agreement 5U01HL069294 from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute and the National Cancer Institute, a contract HHSH234200637015C with Health Resources and Services Administration, 2 grants (N00014-06-1-0704 and N00014-08-1-0058) from the Office of Naval Research, and grants from Allos, Inc., Amgen, Inc., Angioblast, an anonymous donation to the Medical College of Wisconsin, Ariad, Be the Match Foundation, Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association, Buchanan Family Foundation, CaridianBCT, Celgene Corporation, CellGenix, GmbH, Children’s Leukemia Research Association, Fresenius-Biotech North America, Inc., Gamida Cell Teva Joint Venture, Ltd., Genentech, Inc., Genzyme Corporation, GlaxoSmithKline, Kiadis Pharma, The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, The Medical College of Wisconsin, Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Milliman USA, Inc., Miltenyi Biotec, Inc., National Marrow Donor Program, Optum Healthcare Solutions, Inc., Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc., Seattle Genetics, Sigma-τ Pharmaceuticals, Soligenix, Inc., Swedish Orphan Biovitrum, THERAKOS, Inc., and Wellpoint, Inc. The views expressed in this article do not reflect the official policy or position of the National Institutes of Health, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, or any other agency of the US Government.

Authorship

Contribution: W.S. and M.M.H. conceived the idea of the project and wrote the manuscript; W.S., M.M.H., and J.D.R. designed the study; C.S.C., R.N., E.A., R.T.M., J.C., M.E.K., and J.D.R. revised and approved the manuscript; and M.-J.Z. and W.S. performed the statistical analyses.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Wael Saber, Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research, Medical College of Wisconsin, 9200 W. Wisconsin Ave, Suite C5500, Milwaukee, WI 53226; e-mail: wsaber@mcw.edu.

![Figure 3. Adjusted probability of DFS in 694 adult MDS patients by donor source. In multivariate analysis, the risk of treatment failure (death or relapse) was significantly higher with 7 of 8 MUD HCT recipients compared with MRD and 8 of 8 MUD HCT recipients (RR 1.47 [95% CI 1.10-1.96] and 1.29 [95% CI 1.00-1.66], respectively). The risk was not different between 8 of 8 MUD and MRD HCT recipients (RR 1.13, 95% CI 0.91-1.42).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/122/11/10.1182_blood-2013-04-496778/4/m_1974f3.jpeg?Expires=1769832631&Signature=aCKqatSOaUMbLEI3~jq2p0UBddUjaCo22hi63QAKji4~HcYorqjQoffk6TRlkYWVg7ycCJjfJDx9DCDnV-pyt8bTy8IpVIn9navcMJuGvKG93cnxdJJtKWnX0FTDtboGPThCD0iwWOC6DbYxU-KAFmqO6btxxJ9G3AFUoEYT62PVJSBlRDjOv4IGVK0A-Ihr2q7P9CZhJoMsIkFgwEq5MwKJ-LI7bYKbZljQU~MG9JUfgNxiCrFeFofF5ORJtsLcEKPJviOIgydcoXOMbNCln8aXNPXnL5yLvGsrlcsnh-zqodZydH3uOtnvtZ~YwOrijvH9ojO6GFE-6z-uvkavMw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 4. Adjusted probability of overall survival in 701 adult MDS patients by donor source. In multivariate analysis, the risk of all-cause mortality was significantly higher with 7 of 8 MUD HCT recipients compared with MRD and 8 of 8 MUD HCT recipients (RR 1.62 [95% CI 1.21-2.17] and 1.30 [95% CI 1.01-1.68], respectively). The risk was not different between 8 of 8 MUD and MRD HCT recipients (RR 1.24, 95% CI 0.98-1.56).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/122/11/10.1182_blood-2013-04-496778/4/m_1974f4.jpeg?Expires=1769832631&Signature=xB9BfWF40VvXzYzU-9A9mv2wUiQ8YaM~u0pJXDLMKC-i1D8j3RkzSnQGj~WBBgX1SzZdg82ujQm41aATRSJ3ObFg-OXHd1jgwdSOlQj9zrP9v6-HtQ-5Q3uRnHekaTO-KyQrAQwm5r9Q0Z57qekNsGtO5XBLXBnKeFo~NSEAArnuaIbziiaRQAT27rPuOwqvUrxm3Fu1cnk3ZvU6Cqa8TGex3VJocV5q3PBlaQ3UAohokcjvU83-UtGkgKbcfKyfAZvtB7-AgmUDL6RkaczO6jA8RNWWeHAZzJHTOZw1mBwIOIMBpohvysO06sOWXmrzrokP10ufX-~ap9~BgaazPQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)