Key Points

GM-CSF–dependent STAT5 hypersensitivity is detected in 90% of CMML samples and is enhanced by signaling mutations.

Treatment with a GM-CSF–neutralizing antibody and JAK2 inhibitors reveals therapeutic potential.

Abstract

Granulocyte-macrophage–colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) hypersensitivity is a hallmark of juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JMML) but has not been systematically shown in the related human disease chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML). We find that primary CMML samples demonstrate GM-CSF–dependent hypersensitivity by hematopoietic colony formation assays and phospho-STAT5 (pSTAT5) flow cytometry compared with healthy donors. Among CMML patients, the pSTAT5 hypersensitive response positively correlated with high-risk disease, peripheral leukocytes, monocytes, and signaling-associated mutations. When compared with IL-3 and G-CSF, GM-CSF hypersensitivity was cytokine specific and thus a possible target for intervention in CMML. To explore this possibility, we treated primary CMML cells with KB003, a novel monoclonal anti–GM-CSF antibody, and JAK2 inhibitors. We found that an elevated proportion of immature GM-CSF receptor-α(R) subunit-expressing cells were present in the bone marrow myeloid compartment of CMML. In survival assays, we found that myeloid and monocytic progenitors were sensitive to GM-CSF signal inhibition. Our data indicate that a committed myeloid precursor expressing CD38 may represent the progenitor population with enhanced GM-CSF dependence in CMML, consistent with results in JMML. These preclinical data indicate that GM-CSF signaling inhibitors merit further investigation in CMML and that GM-CSFR expression on myeloid progenitors may be a biomarker for this therapy.

Introduction

Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) is a genetically diverse hematologic malignancy characterized by cytopenias with or without leukocytosis, marrow dysplasia, monocytosis, splenomegaly, and a propensity to transform into acute myeloid leukemia (AML).1 Owing to a series of genetic abnormalities that span across a wide array of biological processes, CMML is among the most aggressive and poorly understood chronic myeloid malignancies, with a 3-year overall survival approximating 20%.2-6 CMML is a member of the myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasms (MDS/MPN), as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO), and is subdivided into myelodysplastic or myeloproliferative variants per the French American British group designation.7 On the basis of WHO criteria, patients are subclassified by bone marrow myeloblast percentage into CMML-1 (5%-10%) and CMML-2 (11%-19%)8 categories.

In addition to CMML, juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JMML), a rare pediatric hematologic malignancy, is included among the MDS/MPN group. Although the median age of onset is 2 years, it shares many clinical features of CMML and has a poor overall prognosis. The presence of monocytosis in JMML is associated with selective hypersensitivity to granulocyte-macrophage–colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF). This phenomenon, and hallmark of the disease, was first described in 1991 by hematopoietic colony formation assays (CFAs)9 and was shown to occur in small CMML cohorts of 3 to 7 patients.9,9-11 Although GM-CSF, interleukin (IL)-3, and IL-5 regulate monocytes through a common β-chain, JMML concentration–dependent hypersensitivity is selective for GM-CSF.9 Each of the myeloid-regulating cytokines within the GM-CSF receptor (GM-CSFR) family bind specific α-chains but share a common β-chain necessary for activation.12 In the case of GM-CSF, the α-chains and β-chains combine to form its active heterododecomer complex, allowing for association with Janus kinase 2 (JAK2).13 Receptor interaction and phosphorylation by JAK2 are required for initiating intracellular signaling events that lead to signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)-5, Ras, and phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase activation.14,15 Because GM-CSF signaling is critical for monocyte differentiation and survival, targeting GM-CSF in the therapeutics of JMML in vitro and AML in vivo has been reported, with varying degrees of success.16,17

Considering the mutational and clinical variability among CMML patients and potential for therapeutic intervention, GM-CSF–dependent hypersensitivity should be explored further. Using primary samples from CMML patients, hypersensitivity to GM-CSF was determined by phosphospecific STAT5 flow cytometry (pSTAT5-flow) and by hematopoietic CFAs. The clinical characteristics and impact of known recurrent mutations on GM-CSF–dependent hypersensitivity was also investigated. Cytokine specificity was determined by comparing pSTAT5 in response to GM-CSF, IL-3, and G-CSF and by using a novel, Humaneered monoclonal antibody against GM-CSF (KB003, KaloBios Pharmaceuticals, San Francisco, CA). This humanized antibody directly binds to the cytokine, which interrupts binding to its cognate receptor. In this preclinical study, our use of this GM-CSF–specific monoclonal antibody provides rationale for future clinical development. Preclinical studies with JAK2 inhibitors also indicate the importance of the GM-CSF/JAK/STAT5 axis on cell survival in vitro in CMML.

Methods

Primary patient samples

Bone marrow–mononuclear cells (BM-MNC) were obtained from 20 patients with a pathology-confirmed diagnosis of CMML at the time of sample acquisition. Patient bone marrow aspirates were obtained at the time of diagnosis or at the time of relapse, and all patients gave informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, approved by the Moffitt Cancer Center Scientific Review Committee and the University of South Florida Institutional Review Board.

Specific details about sample collection and informed consent documentation are included in supplemental methods. Individual patient characteristics and a summary of this cohort are provided in supplemental Table 1. For analysis of pSTAT5 in healthy donors, fresh BM-MNCs (n = 7) were purchased from Lonza, Inc. These samples were cryopreserved and archived with the CMML samples.

Determination of pSTAT5 levels

Flow cytometry for the detection of pSTAT5 was examined after treatment with GM-CSF, IL-3, and G-CSF using methods established in JMML.11,18,19 For this assay, BM-MNCs from CMML patients and healthy controls were suspended in prewarmed StemSpan H3000 with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) at a concentration of 1 to 2 million cells/mL for 2 hours at 37°C. Cells were washed and suspended in prewarmed RPMI medium devoid of cytokines or serum for 1 hour at 37°C. The human MO7e cell line was used as a positive control for each assay and was obtained as a generous gift from the laboratory of Ken Zuckerman. This cell line was originally described by Avanzi et al from a human megakaryocytic leukemia cell line and is dependent on exogenous GM-CSF for expansion and survival.20 Growth of this cell line was maintained in IMDM medium, with 10 ng/mL GM-CSF. Approximately 5 × 105 cells were aliquoted into flow cytometry test tubes at a volume of 1 mL per tube. GM-CSF, IL-3, or G-CSF was added at various concentrations for 15 minutes at 37°C. Cells were then fixed and permeabilized, as previously described.11 Anti-pSTAT5 (Alexa 647, BD Biosciences, catalog no. 612599) was added at a concentration of 3 µL per tube in a 100-µL final reaction volume for 30 minutes and washed once with fluorescence-activated cell sorting buffer. All data were acquired on an LSR II flow cytometer and analyzed by Cytobank flow cytometry analysis software in the Moffitt Cancer Center Flow Cytometry Core. Flow cytometry calibration beads and Quantum MESF detection beads were used to account for daily cytometer variation and standardization of fluorescent intensity, respectively.

Sequencing of patient samples

Known mutations in CMML were examined with detailed information provided in supplemental methods.21,22 DNA was unavailable from 2 patients so this subset analysis was performed on 18 of the 20 patients studied for GM-CSF hypersensitivity by pSTAT5-flow (supplemental Table 1). Genes examined included NRAS, KRAS, C-CBL, JAK2, RUNX1, SRSF2, ASXL1, EZH2, and TET2.

Colony-forming assay

Fourteen-day CFAs were conducted using BM-MNCs cultured in GM-CSF, IL-3, G-CSF, or a cytokine cocktail, as described in supplemental methods from seven CMML patients and controls.

Survival assay with KB003

Ten primary, frozen CMML samples were defrosted in prewarmed StemSpan H3000 with 10% FBS at a concentration of 1 to 2 million cells/mL for 2 hours at 37°C. MO7e was used as a positive control. Specific details about the survival assay are provided in supplemental methods.

Treatment with JAK2 inhibitors

The doses of ruxolitinib, SD-1029, CYT-387, and TG-101348 were selected based on previously published reports.23,23-26 After 6 frozen BM-MNCs were thawed as described before, samples were pretreated with their respective JAK2 inhibitor for 1 hour. Next, cells were stimulated with 10 ng/mL of GM-CSF for 15 minutes and fixed, permeabilized, and tested for GM-CSF–dependent pSTAT5, as described before. To determine the impact of JAK2 inhibition on CMML BM-MNC viability, 5 CMML BM-MNCs were treated with class-selective inhibitors for 48 hours and the death of BM-MNC subsets was tested, as described in supplemental methods using the 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) viability assay.

Antibodies

KB003 (human IgG1k) and chimeric LMM10227 antibodies were provided by KaloBios Pharmaceuticals Inc.

Surface plasmon resonance analysis

The binding of glycosylated human GM-CSF (Humanzyme) to chimeric LMM102 and KB003 antibodies was analyzed by surface plasmon resonance on a Biacore 3000 instrument.28 Anti-F(ab’)2 polyclonal antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch) was immobilized on a CM5 chip according to the manufacturer’s protocol.28 KB003 (15 µL; 0.5 µg/mL) or chimeric LMM102 (15 µL; 5 µg/mL) was captured on the anti-F(ab’)2 immobilized chips. Binding experiments were conducted at 37°C with a constant flow rate of 30 µL/minute in phosphate-buffered saline–Tween buffer (0.02 M sodium phosphate buffer with 0.15 M NaCl and 0.05% Tween 20, pH 7.4). Human recombinant GM-CSF was diluted in phosphate-buffered saline–Tween buffer from 25 nM to 0.390 nM and injected for 500 s(s), followed by a 1500-second dissociation time.

GM-CSF neutralization

Human U937 cells (ATCC no. CRL-1593.2) were grown in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% FBS. For induction of IL-8 secretion, recombinant human GM-CSF (R&D Systems, catalog no. 215-GM) was added to the medium for 16 hours for a final concentration of 0.5 ng/mL (a concentration determined to provide 90% maximal induction). The level of IL-8 secreted into the culture supernatant was determined using a human IL-8 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (Anogen, catalog no. EL10008).

GM-CSFR density

BM-MNCs from 15 CMML patients were stained with CD34-PerCPcy5.5, CD38-PECy7, CD11b-Pacific Blue, CD33-PE, and CD14 APC Cy7 to determine myeloid subpopulations. DAPI was used to exclude nonviable cells, and CD116-PE (BD Biosciences #551373) was used to determine the density of GM-CSF on a per-cell basis.29 Flow cytometry calibration beads and Quantum MESF detection beads were used to account for daily cytometer variation and standardization of mean fluorescent intensity, respectively.

Statistical analysis

The percentage of pSTAT5-positive cells and pSTAT5 fluorescence index (FI) at the 95th percentile were compared as continuous variables between CMML cases and controls using linear regression after square root transformation. All flow cytometry data are expressed as a fold change from the cohort’s maximum pSTAT5 level and from the no-drug control when appropriate. Specific details are provided in the supplemental methods. For mutational stratification, patients were grouped by signaling (CBL, KRAS, NRAS, JAK2) (n = 7), epigenetic (TET2, EZH2, ASXL1) (n = 6), splicing (SRSF2) (n = 4), and RUNX1 mutations (n = 3), as described in Table 1 and supplemental Table 1. The continuous variables age, baseline complete blood counts, and percentage of bone marrow blasts were compared with GM-CSF–dependent pSTAT5 using the Pearson’s correlation analysis. All statistical analyses were performed with the GraphPad Prism version 5.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA; www.graphpad.com) with assistance from the Biostatistics Core at Moffitt Cancer Center.

A comparison of clinical characteristics with stimulated pSTAT5 in primary CMML samples

| Variable Type . | Mean (95%CI) stimulated pSTAT5%+ . | Mean (95%CI) stimulated pSTAT5 FI . | Pearson R (95%CI) stimulated pSTAT5%+ . | Pearson R (95%CI) stimulated pSTAT5 FI . | P value: FI, %+ . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Categorical variables | |||||

| WHO | (–0.1492 to 0.06385) | (–0.3307 to 0.1520) | .41, .47 | ||

| CMML-1 (n = 15) | 0.1713 | 0.3287 | |||

| CMML-2 (n = 5) | 0.2140 | 0.4180 | |||

| IPSS35 | (–0.1791 to 0.04663) | (–0.3739 to 0.1451) | .23, .37 | ||

| Lower (n = 16) | 0.1688 | 0.3281 | |||

| Higher (n = 4) | 0.2350 | 0.4425 | |||

| MDASC36 | (–0.1829 to −0.02400) | (–0.4178 to −0.06338) | .014, .011 | ||

| Lower (n = 11) | 0.1355 | 0.2427 | |||

| Higher (n = 9) | 0.2389 | 0.4833 | |||

| MDAPS37 | (–0.1948 to 0.02476) | (–0.4887 to −0.02133) | .12, .034 | ||

| Lower (n = 16) | 0.1650 | 0.3000 | |||

| Higher (n = 4) | 0.2500 | 0.5550 | |||

| DUSS38 | (–0.1996 to 0.05369) | (–0.4552 to 0.1156) | .24, .23 | ||

| Lower (n = 15) | 0.1200 | 0.2067 | |||

| Higher (n = 5) | 0.1929 | 0.3767 | |||

| CYTO | (–0.1139 to 0.09102) | (–0.2160 to 0.2474) | .82, .88 | ||

| Abnormal (n = 6) | 0.1900 | 0.3557 | |||

| Normal (n = 14) | 0.1786 | 0.3400 | |||

| Spleen | (–0.09002 to 0.09802) | (–0.2400 to 0.1840) | .93, .78 | ||

| Enlarged (n = 10) | 0.1840 | 0.3370 | |||

| Normal (n = 10) | 0.1800 | 0.3650 | |||

| Mutations | (*) | (*) | * | ||

| Data available† (n = 18) | 0.1411 | 0.1712 | |||

| No data available (n = 2) | 0.1400 | 0.3700 | |||

| Mutations | (–0.1119 to 0.4736) | (–0.1991 to 0.2818) | .72, .80 | ||

| Present (n = 13) | 0.4159 | 0.2288 | |||

| Absent (n = 5) | 0.2350 | 0.1875 | |||

| RUNX1 | (–0.4310 to 0.2487) | (–0.3627 to 0.1571) | .41, .58 | ||

| Mutation (n = 3) | 0.3033 | 0.1267 | |||

| No mutation (n = 15) | 0.3944 | 0.2295 | |||

| Signaling | (0.06052 to 0.4501) | (–0.009515 to 0.3874) | .055, .037 | ||

| Mutation (n = 7) | 0.5071 | 0.3271 | |||

| No mutation (n = 9) | 0.2518 | 0.1382 | |||

| Epigenetic | (–0.1441 to 0.3358) | (–0.08641 to 0.3514) | .81, 1.00 | ||

| Mutation (n = 6) | 0.4150 | 0.3000 | |||

| No mutation (n = 11) | 0.3192 | 0.1675 | |||

| Splicing | (–0.2634 to 0.2927) | (–0.2756 to 0.2456) | .87, .75 | ||

| Mutation (n = 4) | 0.3625 | 0.2000 | |||

| No mutation (n = 14) | 0.3479 | 0.2150 | |||

| Continuous variables | |||||

| WBC | 0.4984 (0.07155 to 0.7709) | 0.3117 (−0.1519 to 0.6628) | .025, .18 | ||

| MONO | 0.5875 (0.1958 to 0.8175) | 0.3974 (−0.05482 to 0.7144) | .006, .083 | ||

| HGB | −0.05400 (−0.4850 to 0.3981) | −0.1823 (−0.5783 to 0.2831) | .82, .44 | ||

| PLT | −0.1981 (−0.5891 to 0.2680) | −0.2525 (−0.6252 to 0.2140) | .40, .28 | ||

| BM BLAST % | 0.1942 (−0.2718 to 0.5864) | 0.1819 (−0.2836 to 0.5779) | .41, .44 | ||

| Age | 0.2611 (−0.2052 to 0.6308) | 0.2467 (−0.2200 to 0.6214) | .27, .29 |

| Variable Type . | Mean (95%CI) stimulated pSTAT5%+ . | Mean (95%CI) stimulated pSTAT5 FI . | Pearson R (95%CI) stimulated pSTAT5%+ . | Pearson R (95%CI) stimulated pSTAT5 FI . | P value: FI, %+ . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Categorical variables | |||||

| WHO | (–0.1492 to 0.06385) | (–0.3307 to 0.1520) | .41, .47 | ||

| CMML-1 (n = 15) | 0.1713 | 0.3287 | |||

| CMML-2 (n = 5) | 0.2140 | 0.4180 | |||

| IPSS35 | (–0.1791 to 0.04663) | (–0.3739 to 0.1451) | .23, .37 | ||

| Lower (n = 16) | 0.1688 | 0.3281 | |||

| Higher (n = 4) | 0.2350 | 0.4425 | |||

| MDASC36 | (–0.1829 to −0.02400) | (–0.4178 to −0.06338) | .014, .011 | ||

| Lower (n = 11) | 0.1355 | 0.2427 | |||

| Higher (n = 9) | 0.2389 | 0.4833 | |||

| MDAPS37 | (–0.1948 to 0.02476) | (–0.4887 to −0.02133) | .12, .034 | ||

| Lower (n = 16) | 0.1650 | 0.3000 | |||

| Higher (n = 4) | 0.2500 | 0.5550 | |||

| DUSS38 | (–0.1996 to 0.05369) | (–0.4552 to 0.1156) | .24, .23 | ||

| Lower (n = 15) | 0.1200 | 0.2067 | |||

| Higher (n = 5) | 0.1929 | 0.3767 | |||

| CYTO | (–0.1139 to 0.09102) | (–0.2160 to 0.2474) | .82, .88 | ||

| Abnormal (n = 6) | 0.1900 | 0.3557 | |||

| Normal (n = 14) | 0.1786 | 0.3400 | |||

| Spleen | (–0.09002 to 0.09802) | (–0.2400 to 0.1840) | .93, .78 | ||

| Enlarged (n = 10) | 0.1840 | 0.3370 | |||

| Normal (n = 10) | 0.1800 | 0.3650 | |||

| Mutations | (*) | (*) | * | ||

| Data available† (n = 18) | 0.1411 | 0.1712 | |||

| No data available (n = 2) | 0.1400 | 0.3700 | |||

| Mutations | (–0.1119 to 0.4736) | (–0.1991 to 0.2818) | .72, .80 | ||

| Present (n = 13) | 0.4159 | 0.2288 | |||

| Absent (n = 5) | 0.2350 | 0.1875 | |||

| RUNX1 | (–0.4310 to 0.2487) | (–0.3627 to 0.1571) | .41, .58 | ||

| Mutation (n = 3) | 0.3033 | 0.1267 | |||

| No mutation (n = 15) | 0.3944 | 0.2295 | |||

| Signaling | (0.06052 to 0.4501) | (–0.009515 to 0.3874) | .055, .037 | ||

| Mutation (n = 7) | 0.5071 | 0.3271 | |||

| No mutation (n = 9) | 0.2518 | 0.1382 | |||

| Epigenetic | (–0.1441 to 0.3358) | (–0.08641 to 0.3514) | .81, 1.00 | ||

| Mutation (n = 6) | 0.4150 | 0.3000 | |||

| No mutation (n = 11) | 0.3192 | 0.1675 | |||

| Splicing | (–0.2634 to 0.2927) | (–0.2756 to 0.2456) | .87, .75 | ||

| Mutation (n = 4) | 0.3625 | 0.2000 | |||

| No mutation (n = 14) | 0.3479 | 0.2150 | |||

| Continuous variables | |||||

| WBC | 0.4984 (0.07155 to 0.7709) | 0.3117 (−0.1519 to 0.6628) | .025, .18 | ||

| MONO | 0.5875 (0.1958 to 0.8175) | 0.3974 (−0.05482 to 0.7144) | .006, .083 | ||

| HGB | −0.05400 (−0.4850 to 0.3981) | −0.1823 (−0.5783 to 0.2831) | .82, .44 | ||

| PLT | −0.1981 (−0.5891 to 0.2680) | −0.2525 (−0.6252 to 0.2140) | .40, .28 | ||

| BM BLAST % | 0.1942 (−0.2718 to 0.5864) | 0.1819 (−0.2836 to 0.5779) | .41, .44 | ||

| Age | 0.2611 (−0.2052 to 0.6308) | 0.2467 (−0.2200 to 0.6214) | .27, .29 |

Overall Cohort (n = 20).

WBC, white blood cell count at time of sample; HGB, hemoglobin level at time of sample; PLT, platelet count at time of sample; MONOS, peripheral monocyte count at time of sample; BLAST, percent myeloblast in the bone marrow aspiration differential; CYTO, cytogenetics at time of sample (abnormal or not); Spleen, spleen enlarged at any time.

Categorical variables were analyzed using the unpaired Student t test with Welch’s correction. Continuous variables were analyzed using the Pearson model.

Number too small for statistics.

No DNA available (2 of 20).

Results

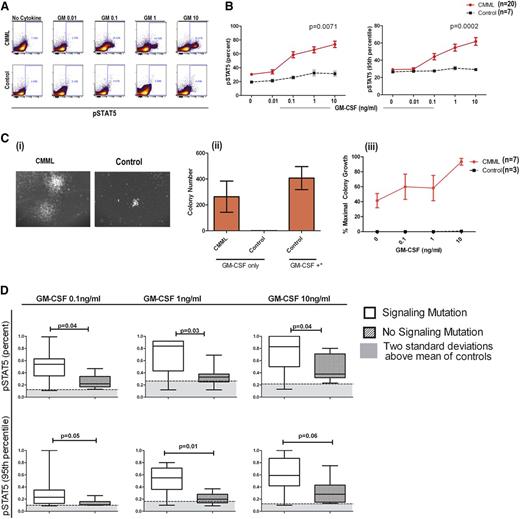

CMML displays GM-CSF-dependent hypersensitivity

Hypersensitivity testing to GM-CSF signaling is a standard criterion for the diagnosis of JMML.1 In an effort to facilitate efficient clinical testing, pSTAT5-flow has been developed and found to correlate with GM-CSF hypersensitivity by CFAs.11 In a previous study of 5 CMML patient samples, pSTAT5 activation in response to low-dose GM-CSF suggested that cytokine hypersensitivity is a feature of CMML.9 Using the JMML-established pSTAT5-flow assay, treatment with GM-CSF in healthy donors and in CMML BM-MNCs resulted in a significant induction of positive cells (Figure 1A). The percentage of pSTAT5-positive cells and the average FI per cell were compared in CMML patients and controls. Both the percentage of positive cells (P = .0071) and the molecules of pSTAT5 per cell (P = .0002) were significantly higher in CMML patients than in controls (Figure 1B). Eighteen of the 20 CMML patients (90%) displayed a GM-CSF–dependent pSTAT5 response at 0.1 ng/mL that was >2 standard deviations above that of controls meeting our criterion for hypersensitivity defined a priori.

GM-CSF–dependent pSTAT5 hypersensitivity is a feature of CMML. (A) As shown in a representative CMML sample and healthy control sample stimulated with increasing doses of GM-CSF, a distinct population of CMML primary cells becomes pSTAT5-positive at 0.1 ng/mL of GM-CSF, which does not occur in normal controls. The percentage of positive cells is indicated on the flow cytometry dot plot. (B) Bone marrow samples from 20 unique CMML patients (solid red line) were compared with 7 normal healthy controls (broken black line) after treatment with increasing doses of GM-CSF (0.01, 0.1, 1, and 10 ng/mL). All pSTAT5 flow cytometry data are expressed relative to the maximal cellular response. Data were normalized using square root transformation. P values are indicated where significant differences were detected using linear regression analysis. (Ci) Representative colonies from a CMML sample and normal control after treatment with 10 ng/mL of GM-CSF only. (Cii) Bar graph of colony numbers generated from CMML (n = 7) and healthy donors (n = 3) with GM-CSF (10 ng/mL) alone. As a positive control, GM-CSF (MethoCult H4034 Optimum), IL-6, IL-3, erythropoietin, and stem cell factor (GM-CSF+*) were added to demonstrate the capacity for colony formation by healthy control bone marrow. (Ciii) Spontaneous colonies without the addition of GM-CSF (0 ng/mL of GM-CSF) and the percent maximum colony-forming units in the presence of GM-CSF alone at increasing doses (0.1, 1, and 10 ng/mL) from CMML patients (solid red line) and controls (broken black line). Error bars represent standard error of the mean in each group. (D) Samples were placed in the signaling mutation group if a mutation in CBL (n = 5), JAK2 (n = 0), KRAS (n = 0), and/or NRAS (n = 2) was identified (n = 7). GM-CSF–dependent pSTAT5 response was compared with those without a signaling mutation (n = 11).

GM-CSF–dependent pSTAT5 hypersensitivity is a feature of CMML. (A) As shown in a representative CMML sample and healthy control sample stimulated with increasing doses of GM-CSF, a distinct population of CMML primary cells becomes pSTAT5-positive at 0.1 ng/mL of GM-CSF, which does not occur in normal controls. The percentage of positive cells is indicated on the flow cytometry dot plot. (B) Bone marrow samples from 20 unique CMML patients (solid red line) were compared with 7 normal healthy controls (broken black line) after treatment with increasing doses of GM-CSF (0.01, 0.1, 1, and 10 ng/mL). All pSTAT5 flow cytometry data are expressed relative to the maximal cellular response. Data were normalized using square root transformation. P values are indicated where significant differences were detected using linear regression analysis. (Ci) Representative colonies from a CMML sample and normal control after treatment with 10 ng/mL of GM-CSF only. (Cii) Bar graph of colony numbers generated from CMML (n = 7) and healthy donors (n = 3) with GM-CSF (10 ng/mL) alone. As a positive control, GM-CSF (MethoCult H4034 Optimum), IL-6, IL-3, erythropoietin, and stem cell factor (GM-CSF+*) were added to demonstrate the capacity for colony formation by healthy control bone marrow. (Ciii) Spontaneous colonies without the addition of GM-CSF (0 ng/mL of GM-CSF) and the percent maximum colony-forming units in the presence of GM-CSF alone at increasing doses (0.1, 1, and 10 ng/mL) from CMML patients (solid red line) and controls (broken black line). Error bars represent standard error of the mean in each group. (D) Samples were placed in the signaling mutation group if a mutation in CBL (n = 5), JAK2 (n = 0), KRAS (n = 0), and/or NRAS (n = 2) was identified (n = 7). GM-CSF–dependent pSTAT5 response was compared with those without a signaling mutation (n = 11).

Clinical characteristics of GM-CSF–hypersensitive patients

CMML patient characteristics were compared with the percentage and FI of pSTAT5-positive cells as continuous variables, and results are shown in Table 1. We found that FI and the percentage of pSTAT5 were distributed equally by age. No statistically significant difference was observed by International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS), the MD Anderson Prognostic Score (MDAPS), Dusseldorf score (DS), hemoglobin level, platelet count, bone marrow blast percentage, or the presence of splenomegaly. However, the pSTAT5 response (FI and % positive) at GM 0.1 ng/mL differed by white blood cell (WBC) count, monocyte count, and MD Anderson Scoring System (MDASC) (P = .014 and P = .01, respectively), consistent with pathological relevance.35-38 The percentage of pSTAT5 (using square root–transformed data) correlated significantly with the peripheral monocyte count (r = 0.5875, P = .006), and the FI showed a similar trend (r = 0.0.3974, P = .083). WBC count was also significantly associated with the percentage (r = 0.4984, P = .025), but not FI (r = 0.3117, P = .18), using square root–transformed pSTAT5 data.

DNA samples were examined for the presence of recurrent mutations, and the percentage of pSTAT5 and FI (as continuous variables) was compared by mutation status. Supplemental Table 1 defines individual mutations in this cohort. In comparing patients without a mutation (n = 5) with those with a mutation (n = 13), there was no difference in percent or FI of pSTAT5 at a dose of 0.1 ng/mL of GM-CSF (Table 1). Levels of GM-CSF response were also similar among patients with mutations in RUNX1, splicing, and epigenetic modifiers when compared with the cohorts without these mutations, as shown in Table 1. However, the mean percentage of pSTAT5-positive cells relative to maximal response (1.0) to GM-CSF in patients with a signaling mutation was 0.5 compared with 0.2 in those without a signaling mutation (P = .037). A difference in FI was also observed (mean of 0.3 with signaling mutations vs 0.1 with no signaling mutations, P = .05) in this cohort. Signaling mutations were associated with a greater responsive to GM-CSF at a dose of 1 and 10 ng/mL, as shown in Figure 1D, indicating that this mutation class intensifies the pSTAT5 response in CMML.

Hypersensitivity to GM-CSF confirmed by colony formation

In a subset of patients with sufficient cryopreserved cells for analysis, GM-CSF hypersensitivity was confirmed using hematopoietic CFAs (n = 7). Hematopoietic colonies were defined as a cluster of >50 cells in MethoCult solution. Only BM-MNCs from CMML patients formed colonies with 0.1 ng/mL of GM-CSF in the absence of other hematopoietic growth factors, as shown in 1 representative case (Figure 1Ci) and quantified in 7 CMML cases (Figure 1Cii). Under these conditions, colony formation was dose dependent, with concentrations of GM-CSF ranging from 0.1 to 10 ng/mL (Figure 1Ciii). Although the BM-MNCs from healthy donors were nonresponsive to low-dose GM-CSF alone, colonies were present in MethoCult solution containing a cocktail of hematopoietic cytokines, including GM-CSF, IL-6, IL-3, erythropoietin, and stem cell factor at doses >10 ng/mL (Figure 1Cii), indicating that the hematopoietic progenitors were capable of differentiation and growth.

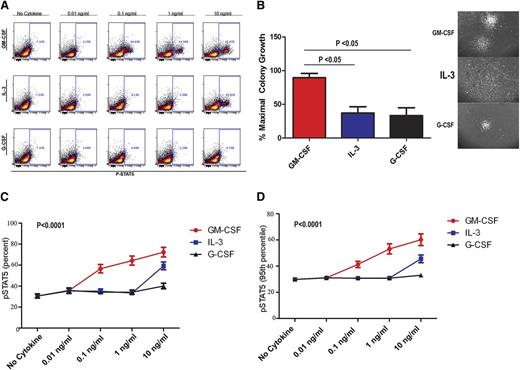

pSTAT5 and colony growth selective for GM-CSF

To confirm the selectivity to GM-CSF, pSTAT5 (Figure 2A) and CFA (Figure 2B) response was also examined after treatment with IL-3 and G-CSF using BM-MNCs from CMML samples and healthy controls. In the patient samples tested, significantly more colonies formed in the presence of GM-CSF compared with IL-3 and G-CSF. Furthermore, the morphologic appearance of colonies in response to GM-CSF was distinct (Figure 2B). Large, compact, and organized colonies were present after GM-CSF treatment, whereas the colonies induced by IL-3 were diffuse and less organized. Colonies induced by G-CSF were small and rarely detected. Essentially, all colonies were of CFU-GM morphology, suggesting an expansion in the granulocyte-macrophage progenitors in these assays. Both the percentage of pSTAT5-positive cells (Figure 2C) and the average molecules of pSTAT5 per cell (95th FI; Figure 2D) were statistically higher in the GM-CSF–treated cells compared with IL-3 and G-CSF (P < .0001). As expected, both G-CSF and IL-3 induced a detectable pSTAT5 response at 10 ng/mL (Figure 2A,C-D).

GM-CSF–dependent pSTAT5 hypersensitivity is cytokine-specific. (A) Representative flow dot plots from CMML samples stimulated with GM-CSF, IL-3, or G-CSF at 0.01, 0.1, 1, and 10 ng/mL. The percentage of pSTAT5-positive cells is indicated in each dot plot. (B) Representative colonies in methyl cellulose generated after treatment with G-CSF, IL-3, and GM-CSF at 10 ng/mL alone. (C) Percentage and (D) 95th FI of pSTAT5-positive cells from CMML patients treated with increasing doses (0.01, 0.1, 1, and 10 ng/mL) of GM-CSF, IL-3, or G-CSF. All pSTAT5 flow cytometry data are expressed as fold change from the cohort’s highest pSTAT5 level. Data were normalized using square root transformation. Significant P values are indicated using linear regression analysis.

GM-CSF–dependent pSTAT5 hypersensitivity is cytokine-specific. (A) Representative flow dot plots from CMML samples stimulated with GM-CSF, IL-3, or G-CSF at 0.01, 0.1, 1, and 10 ng/mL. The percentage of pSTAT5-positive cells is indicated in each dot plot. (B) Representative colonies in methyl cellulose generated after treatment with G-CSF, IL-3, and GM-CSF at 10 ng/mL alone. (C) Percentage and (D) 95th FI of pSTAT5-positive cells from CMML patients treated with increasing doses (0.01, 0.1, 1, and 10 ng/mL) of GM-CSF, IL-3, or G-CSF. All pSTAT5 flow cytometry data are expressed as fold change from the cohort’s highest pSTAT5 level. Data were normalized using square root transformation. Significant P values are indicated using linear regression analysis.

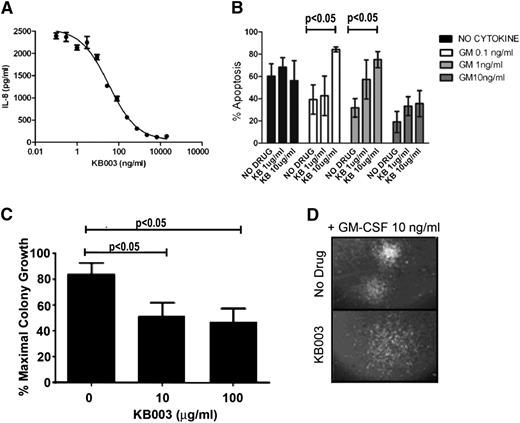

KB003 can bind to GM-CSF and affect survival in a GM-CSF–dependent cell line (MO7e) and CMML BM-MNCs

KB003 is an antibody to GM-CSF that interacts with a previously defined epitope, recognized by the LMM102 antibody.27 The antibody was humanized for future therapeutic application by KaloBios Pharmaceuticals. Surface plasmon resonance analysis was used to compare binding kinetics for the interaction of KB003 or the chimeric LMM102 reference antibody to glycosylated human GM-CSF.28 KB003 or the LMM102 reference antibody was captured onto the Biacore chip surface, and GM-CSF was used as the analyte. Kinetic constants were determined in 2 independent experiments (Table 2). GM-CSF is a monomeric molecule in solution; therefore, this assay determines the monovalent affinity for binding of GM-CSF to antibody. Similar association constants, dissociation constants, and calculated affinities were found using the two related antibodies (LMM102 and KB003).

Binding kinetics of anti–GM-CSF antibodies determined by surface plasmon resonance analysis

| Anti-GM-CSF antibody . | ka, M–1s−1 . | kd, s−1 . | KD, pM . |

|---|---|---|---|

| LMM102 | 7.20 × 105 | 2.2 × 10−5 | 30.5 |

| KB003 | 2.86 × 105 | 7.20 × 10−6 | 25.1 |

| Anti-GM-CSF antibody . | ka, M–1s−1 . | kd, s−1 . | KD, pM . |

|---|---|---|---|

| LMM102 | 7.20 × 105 | 2.2 × 10−5 | 30.5 |

| KB003 | 2.86 × 105 | 7.20 × 10−6 | 25.1 |

ka, association constant (ka); kd, dissociation constant; KD, calculated affinity.

KB003 was captured on anti-F(ab)2–coated surface in a Biacore 3000 instrument. GM-CSF was injected over the surface at multiple concentrations and global fit analysis carried out assuming a 1:1 interaction. Data are means from 2 independent assays at 37°C.

Next, the KB003 antibody was used to determine its ability to neutralize GM-CSF activity. This assay was performed using the human U937 cell line, which has been reported to secrete IL-8 in response to GM-CSF treatment.30 A dose-dependent reduction in IL-8 secretion was evident after incubation with KB003 (Figure 3A), indicating that the antibody is functional. KB003 inhibited GM-CSF activity with a mean IC50 from 3 independent assays of 48.2 ng/mL.

KB003 effectively neutralizes GM-CSF. (A) Inhibition of GM-CSF–induced IL-8 secretion from U937 cells. KB003 at various concentrations was incubated with U937 cells in the presence of 0.5 ng/mL GM-CSF for 16 hours (a concentration of GM-CSF providing 90% of maximal induction). IL-8 secreted into the culture supernatant was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Results from a representative assay carried out in triplicate are shown. Mean IC50 from 3 independent assays was 48.2 ng/mL. (B) MO7e human cells were cultured with doses of GM-CSF ranging from 0 to 10 ng/mL and increasing doses of KB003. Annexin V was used to measure apoptosis and viability at 48 hours. (C) Three distinct CMML patient aspirates cultured with GM-CSF (10 ng/mL) and increasing doses of KB003. Clusters of cells of >50 were measured. (D) Representative hematopoietic colony with and without KB003. Colonies appear less organized in the drug-treated group. Significant P values are indicated using one-way analysis of variance.

KB003 effectively neutralizes GM-CSF. (A) Inhibition of GM-CSF–induced IL-8 secretion from U937 cells. KB003 at various concentrations was incubated with U937 cells in the presence of 0.5 ng/mL GM-CSF for 16 hours (a concentration of GM-CSF providing 90% of maximal induction). IL-8 secreted into the culture supernatant was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Results from a representative assay carried out in triplicate are shown. Mean IC50 from 3 independent assays was 48.2 ng/mL. (B) MO7e human cells were cultured with doses of GM-CSF ranging from 0 to 10 ng/mL and increasing doses of KB003. Annexin V was used to measure apoptosis and viability at 48 hours. (C) Three distinct CMML patient aspirates cultured with GM-CSF (10 ng/mL) and increasing doses of KB003. Clusters of cells of >50 were measured. (D) Representative hematopoietic colony with and without KB003. Colonies appear less organized in the drug-treated group. Significant P values are indicated using one-way analysis of variance.

The ability of KB003 to neutralize GM-CSF–dependent survival of MO7e was determined. Cells were cultured in the presence or absence of GM-CSF with or without KB003. A significant dose-dependent increase in the percentage of apoptotic cells was seen in the presence of all doses of GM-CSF tested when KB003 was added at doses ranging from 1 to 10 μg/mL (Figure 3B).

To determine whether KB003 is capable of reducing CMML cells in vitro, primary BM-MNCs from 10 patients with GM-CSF hypersensitivity were used for hematopoietic CFAs. These assays were performed in the presence of GM-CSF (10 ng/mL) with increasing doses of KB003 (n = 7) compared with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) control. Hematopoietic colonies were dose-dependently decreased with KB003 (Figure 3C). These quantitative differences were accompanied by qualitative differences in colony morphology, because colonies generated in the presence of KB003 were less organized and more diffuse than controls (Figure 3D).

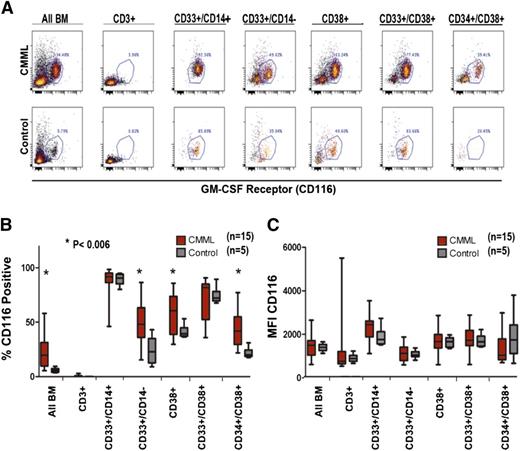

GM-CSFR density is not increased in our CMML cohort compared with controls

It is possible that GM-CSF–selective hypersensitivity could result from overexpression of the α-chain of the GM-CSFR (CD116). Therefore, GM-CSFRα density (CD116 expression) was compared in CMML patients and controls by flow cytometry. Selective myeloid subsets were examined including CD33+/CD14–, CD38+, CD33+/CD38+, and CD34+/CD38+. Patients with CMML have a higher percentage of cells within each of the subsets examined, consistent with expansion of the entire myeloid population (Figure 4A). Among the cells in each subset, we determined the proportion of cells that expressed CD116 in CMML and healthy controls. As expected, the highest percentage of CD116+ cells was present in myeloid cells and lowest in CD3+ T lymphocytes (Figure 4). All CD33+/CD14+ immature monocytes expressed CD116 in both patient and control samples; however, the proportion of CD116-positive CD33+/CD14– immature myeloid cells, CD38+ cells, and CD34+/CD38+ immature hematopoietic progenitors was increased significantly among CMML patients (P < .006, Figure 4B), suggesting that the percentage of GM-CSFRα–expressing cells may be a marker of CMML clonal burden within the immature population.

GM-CSFR (CD116) expression on BM-MNCs in CMML vs control. (A) Dot plot of a representative CMML sample and healthy control stained with anti-CD116 and analyzed by multicolor flow cytometry. (B) Fifteen unique CMML samples and 5 healthy controls gated by myeloid subpopulation (CD 3+negative control) and stained with anti-CD116 measured by (C) the percent positive CD116 cells (D) and the mean fluorescent intensity of CD116. Significant P values are indicated using a paired Student t test.

GM-CSFR (CD116) expression on BM-MNCs in CMML vs control. (A) Dot plot of a representative CMML sample and healthy control stained with anti-CD116 and analyzed by multicolor flow cytometry. (B) Fifteen unique CMML samples and 5 healthy controls gated by myeloid subpopulation (CD 3+negative control) and stained with anti-CD116 measured by (C) the percent positive CD116 cells (D) and the mean fluorescent intensity of CD116. Significant P values are indicated using a paired Student t test.

In contrast to the percentage of some myeloid populations expressing this receptor, the molecular density was indistinguishable in patients and controls within all myeloid subsets. Importantly, there was no evident difference in CD116 FI among immature monocytes, defined as CD33+/CD14+ (Figure 4C). These results suggest that GM-CSFR overexpression does not mediate the GM-CSF hypersensitivity in CMML. organized

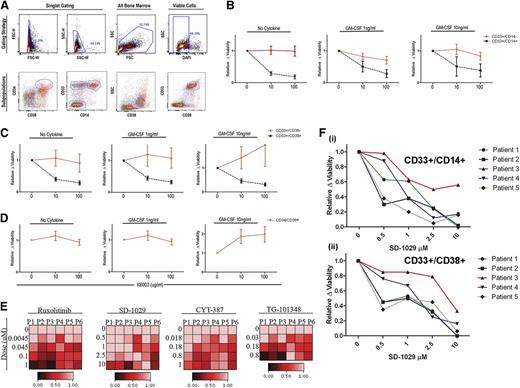

Sensitivity of myeloid subsets to KB003 and JAK2 inhibition

The sensitivity of myeloid subpopulations was examined using KB003. Because CD38+ cells are reported to be the most pSTAT5-responsive in JMML,11 this population was specifically examined for sensitivity to KB003. BM-MNCs were microcultured in the presence of KB003, FBS, and increasing doses of GM-CSF. After 48 hours, these cultures were analyzed using a flow cytometry myeloid panel and DAPI to determine viability. The percentage of distinct myeloid subpopulations within the viable gate was normalized to cells cultured without KB003 (Figure 5A).

KB003 impacts in vitro decreases in proliferation and viability in monocytic precursors. (A) The flow cytometry gating strategy used to determine the viability of specific subpopulations in each CMML sample is shown. Immature myeloids were defined as CD33-positive and CD14-negative. Immature monocytes were defined as CD33-positive and CD14-positive. Myeloid progenitor cells were further analyzed using CD34 and CD38 as shown. (B-D) Ten different CMML patient samples were tested (each in duplicate) to determine the viability of CMML subpopulations in the presence of increasing doses of KB003 and GM-CSF. Only viable cells were considered in the analysis, and all data were normalized to the no drug–treated group. Myeloid subpopulations were grouped as shown, and a one-way analysis of variance was done to compare the percentage of cells within the viable gate at each dose of KB003. Significant P values represent a comparison within each subpopulation. (E) A heat map was generated using DMSO (0) and increasing doses (as shown) to each individual JAK2 inhibitor (ruxolitinib, SD-1029, CYT-387, TG-101348). The percentage of GM-CSF (10 ng/mL)–dependent pSTAT5-responsive cells as measured by flow cytometry is shown relative to the maximal GM-CSF response in the presence of DMSO (drug vehicle control). Six individual CMML patient samples were analyzed (P1-P6). (F) Dose-response curves for 5 CMML BM-MNC subsets CD33+/CD14+ (Fi) and CD33+/CD38+ (Fii) treated for 48 hours with a representative JAK2 inhibitor (SD-1029). Viability is relative to the DMSO drug vehicle control and was measured using a viability stain (DAPI) by flow cytometry.

KB003 impacts in vitro decreases in proliferation and viability in monocytic precursors. (A) The flow cytometry gating strategy used to determine the viability of specific subpopulations in each CMML sample is shown. Immature myeloids were defined as CD33-positive and CD14-negative. Immature monocytes were defined as CD33-positive and CD14-positive. Myeloid progenitor cells were further analyzed using CD34 and CD38 as shown. (B-D) Ten different CMML patient samples were tested (each in duplicate) to determine the viability of CMML subpopulations in the presence of increasing doses of KB003 and GM-CSF. Only viable cells were considered in the analysis, and all data were normalized to the no drug–treated group. Myeloid subpopulations were grouped as shown, and a one-way analysis of variance was done to compare the percentage of cells within the viable gate at each dose of KB003. Significant P values represent a comparison within each subpopulation. (E) A heat map was generated using DMSO (0) and increasing doses (as shown) to each individual JAK2 inhibitor (ruxolitinib, SD-1029, CYT-387, TG-101348). The percentage of GM-CSF (10 ng/mL)–dependent pSTAT5-responsive cells as measured by flow cytometry is shown relative to the maximal GM-CSF response in the presence of DMSO (drug vehicle control). Six individual CMML patient samples were analyzed (P1-P6). (F) Dose-response curves for 5 CMML BM-MNC subsets CD33+/CD14+ (Fi) and CD33+/CD38+ (Fii) treated for 48 hours with a representative JAK2 inhibitor (SD-1029). Viability is relative to the DMSO drug vehicle control and was measured using a viability stain (DAPI) by flow cytometry.

As expected, the immature monocytes were more sensitive to KB003 at all doses of GM-CSF (Figure 5B) compared with CD33+/CD14– cells. Subdividing the CD33+ cells into those that are CD38+ vs CD38–, we found that the CD33+/CD38+ were extremely sensitive to GM-CSF inhibition by KB003, with a significant decrease in the proportion of viable cells (P < .05) after treatment with 10 and 100 µg/mL of KB003 (Figure 5C). In contrast, CD33+/CD38– cells were less sensitive to drug suppression. Because the CMML stem cell population is currently unknown, we compared KB003 sensitivity in CD34+/CD38+ cells and found no decrease in viable cells in response to KB003 treatment (Figure 5D). However, insufficient viable cells in the CD34+/CD38– population were available for analysis.

Because JAK2 is the sentinel kinase in the GM-CSF-pSTAT5 axis, we treated CMML BM-MNCs with a panel of JAK2 inhibitors including ruxolitinib, SD-1029, CYT-387, and TG-101384 to determine this kinase’s role in the abnormal GM-CSF signaling response. After pretreatment (n = 6) for 1 hour, GM-CSF–dependent pSTAT5 dose–dependent decreases were seen with all inhibitors (Figure 5E) tested. SD-1029 was then cultured with primary BM-MNCs and 10 ng/mL of GM-CSF to determine the impact on viability (n = 5). In the same manner that KB003 preferentially decreased viability of immature myeloid and monocytic progenitors, treatment with this JAK2 inhibitor also resulted in a dose-dependent decrease in viability of CD33+/CD14+ (Figure 5Fi) and CD33+/CD38+ populations (Figure 5Fii). The CD34+/CD38+ cells were insensitive to JAK2 inhibition (data not shown).

Discussion

Nearly all JMML patients exhibit dose-dependent activation of pSTAT5 in response to GM-CSF. This cytokine-specific response is exclusively present in JMML compared with healthy controls and other pediatric MPNs, indicating that it is critical for disease pathogenesis. Preclinical studies using diphtheria-conjugated GM-CSF have justified targeting this pathway in a clinical trial in AML.17 Unfortunately, the diphtheria-toxin conjugate demonstrated an unacceptable hepatic toxicity profile that prevented further clinical evaluation.16 Murine models of CMML/JMML indicate that activation of the Ras pathway is sufficient to induce GM-CSF–dependent pSTAT5 hypersensitivity and mediate monocyte progenitor expansion.31 Based on these data, we explored this signaling cascade in CMML. GM-CSF hypersensitivity by colony formation alone has been reported in CMML, but had not been extensively evaluated.9,9-11 By performing CFAs, pSTAT5 flow cytometry, and survival assays with GM-CSF-signaling neutralization, we show that CMML has a phenotypic abnormality similar to JMML. We also demonstrate that this phenomenon is cytokine specific, because low doses of IL-3 or G-CSF did not induce pSTAT5 signals or induce the growth of organized hematopoietic colonies.

Our results indicate that the vast majority of CMML patients respond more vigorously to GM-CSF treatment and the percentage of GM-CSFR–positive immature myeloid cells is increased. Clinically this is important because apoptotic induction was evident in CMML BM-MNCs upon GM-CSF neutralization, suggesting that molecular events contributing to monocyte differentiation or proliferation may be similar in JMML and CMML. The genetic events leading to GM-CSF hypersensitivity in JMML are clearly linked to mutations involving the Ras pathway.32 JMML is a more genetically homogenous disease, whereas CMML is characterized by genetic lesions spanning epigenetic, splicing, and signaling pathways that converge into a relatively similar clinical phenotype.5,6,33 As such, we investigated the mutation profile of our cohort and correlated mutation status to GM-CSF response. Our results indicate that patients with signaling mutations indeed have greater sensitivity to GM-CSF. Mutations in the Ras/CBL/JAK2 signaling pathway are, however, not essential for the common phenotype because 90% of CMML patients in this cohort exhibited the GM-CSF hypersensitive response. Patients in this cohort without detectable mutations and patients with other types of mutations were also hypersensitive to GM-CSF compared with healthy controls. Moreover, the level of hypersensitivity (percentage of responsive cells and FI) was an indicator of disease severity. Monocyte count and higher-risk MDASC were both associated with the degree of GM-CSF pSTAT5. Our data suggest that these divergent molecular events may mediate responses that converge within the GM-CSF/pSTAT5 pathway by an unknown mechanism that correlates with disease progression.

Even in JMML, the mechanism by which GM-CSF–dependent pSTAT5 sensitivity occurs is unknown and under investigation. The precise interaction between mutations in proteins involved in Ras signaling, such as PTPN11, NRAS, and CBL, and pSTAT5 activation is unclear.34 The matter is likely more complicated in CMML considering its genetic heterogeneity and thus requires comprehensive annotation of the mutations to unravel. However, we did consider the possibility that GM-CSFR density may be increased in CMML. Aberrant receptor expression was not detected on any of the myeloid subsets, suggesting that this is not the mechanism underlying the hyperactive pSTAT5 response. Interestingly, the percentage of GM-CSFR+ (ie, CD116+) myeloid and monocytic precursors was increased compared with controls, which may reflect the clonal burden within the diseased bone marrow. To this end, CD34/CD38/CD116 positivity may represent a phenotypic marker of tumor burden in CMML and requires prospective validation.

Finally, we tested whether GM-CSF signaling is a potential therapeutic target in CMML. GM-CSF neutralization significantly decreased the number of colonies and morphologic organization in CMML BM-MNCs in CFAs. Furthermore, our flow cytometry–based viability assay demonstrated that the CD33+/CD14+ and CD33+/CD14–/CD38+ subsets were most sensitive to GM-CSF blockade and JAK2 inhibition, which is consistent with JMML data.11 However, it is noted that the CD34-positive subset was insensitive to GM-CSF signal inhibition, suggesting that this strategy is unlikely to yield a curative therapeutic because it is possible that the CD34 subset includes, at least in part, the leukemia-initiating cell. It remains unclear whether suppression of this myeloid progenitor population is necessary to avoid risk of AML transformation or chronic anemia. Because these 2 events represent the major source of morbidity and mortality in this patient population, future therapeutic trials should incorporate biomarker analysis for the CD34 population. Taken together, however, we believe that the GM-CSF signaling cascade is an excellent CMML-specific therapeutic target, and clinical studies are ongoing to test KB003 and JAK2 inhibitor therapeutic activity in this disease.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jodi L. Kroeger and the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center flow cytometry core for their invaluable technical assistance. The authors would like to thank the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center Genomics and Biostatistics core for their invaluable technical assistance. The authors also thank Rasa Hamilton for manuscript editing. This work was performed at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center. Sequencing of selected genes was performed at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center.

This work was generously funded by KaloBios Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and the Edward P. Evans Foundation.

Authorship

Contribution: E.P. designed research, performed research, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript; J.S.P., A.W.M., K.M., M.B., C.B., G.Y., O.A.-W., E.K., S.K., and J.M.M. performed research, assisted in manuscript preparation, and analyzed data; J.L., A.F.L., and R.S.K. assisted in experimental design and sample collection; and P.K.E.-B. assisted in research design, performed statistical analysis, and wrote manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.B., C.B., and G.Y. have been or are currently employed by KaloBios Pharmaceuticals, Inc. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Eric Padron, 12902 Magnolia Dr, MRC 3047A, Tampa, FL 33612; e-mail: eric.padron@moffitt.org.