Abstract

SF3B1 is a critical component of the splicing machinery, which catalyzes the removal of introns from precursor messenger RNA (mRNA). Next-generation sequencing studies have identified mutations in SF3B1 in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) at high frequency. In CLL, SF3B1 mutation is associated with more aggressive disease and shorter survival, and recent studies suggest that it can be incorporated into prognostic schema to improve the prediction of disease progression. Mutations in SF3B1 are predominantly subclonal genetic events in CLL, and hence are likely later events in the progression of CLL. Evidence of altered pre-mRNA splicing has been detected in CLL cases with SF3B1 mutations. Although the causative link between SF3B1 mutation and CLL pathogenesis remains unclear, several lines of evidence suggest SF3B1 mutation might be linked to genomic stability and epigenetic modification.

Introduction

The advent of next-generation sequencing has been transformative for understanding the molecular underpinnings of cancer, including the blood malignancies. One of the most surprising findings arising from the recent next-generation sequencing data has been the discovery of mutated splicing factor 3b1 (SF3B1) as a putative candidate driver gene of the common lymphoid malignancy, chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). This discovery has been particularly revealing in CLL because it had been long suspected that distinct subgroups of the disease exist based on its highly variable clinical course, ranging from indolent disease in some patients to a rapidly fatal course despite aggressive therapy in others.1 By now, massively parallel DNA sequencing and targeted DNA sequencing have been undertaken in >250 and 3800 CLL cases, respectively, and have consistently identified SF3B1 as one of the most frequently mutated genes in CLL in 5% to 18% of patients, depending on the composition of the various cohorts in terms of the proportion of cases at presentation, at the time of treatment or at disease progression.2-4 Contemporaneously, a high frequency of mutation in SF3B1 was identified in a variant of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) (refractory anemia with ringed sideroblasts), suggesting that altered splicing may be an important pathogenic mechanism in blood malignancies and cancer. Herein, we review the emerging understanding of the impact of SF3B1 mutations on the clinical outcome of CLL patients and stepwise transformation of CLL, and discuss the potential mechanisms by which SF3B1 mutation is linked to the pathobiology of CLL.

Identification of mutated SF3B1 as a putative CLL driver

Initial studies to characterize the mutational landscape of CLL using whole-genome sequencing and whole-exome sequencing (WES) unexpectedly revealed a high frequency of nonsilent heterozygous mutations in CLL.2-4 Subsequent studies in CLL, summarized in Table 1,3,5-8 have confirmed that mutated SF3B1 consistently ranks among the most commonly identified somatic mutations in CLL, together with other putative CLL-associated driver mutations in TP53, ATM, MYD88, BIRC3, and NOTCH1.

Incidence of SF3B1 mutation in CLL varies depending on disease status

| Disease status . | Incidence (%) . | No. of subjects in cohort . | Reference . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Newly diagnosed | 3.6 | 360 | 5 |

| 5 | 301 | 3 | |

| 9.3 | 1124 | 6 | |

| Firstline treatment | 17 | 437 | 7 |

| 18.4 | 621 | 8 | |

| Treatment refractory | 17 | 59 | 3 |

Because SF3B1 is a critical component of the splicing machinery, the discovery of a high frequency of SF3B1 mutations in CLL has highlighted the essential pathway (in which the introns from precursor messenger RNAs [pre-mRNAs] are removed) as involved in CLL. Splicing is catalyzed by the spliceosome, which consists of a set of small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particles (snRNPs), namely U1, U2, U4, U5, and U6, as well as numerous splicing factors.9 SF3B1 is an essential component of the U2 snRNP.

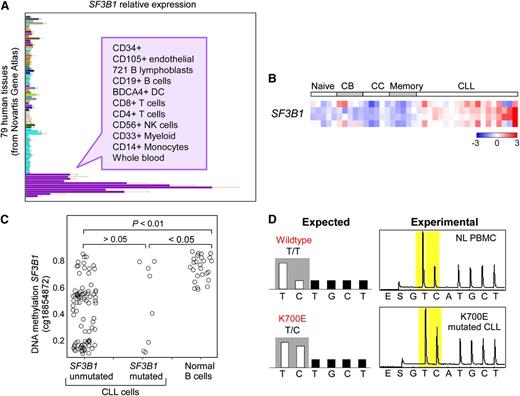

The vast majority of mutations in SF3B1 are localized to its highly conserved C-terminal domain, which comprises 22 Huntington Elongation Factor 3 PR65/A TOR (HEAT) repeats. As shown in Figure 1, most mutations have been detected between the fifth to the eighth HEAT repeats (encoded by exons 14-16), with K700E as the most frequently mutated site (50% of reported cases). A second hot spot has been detected at G742 (19%), with additional common sites at K666 (12%) and H662 (4%). All of these hot-spot mutations occur within highly conserved sequences, even to Caenorhabditis elegans, suggesting that they occur in functionally important regions. As aforementioned, SF3B1 mutations have been also predominantly identified in MDS (76% of patients with ringed sideroblasts), and in breast (2%) and pancreatic cancers (3%),10-14 at sites similar to those in CLL (ie, most commonly at K700E, Figure 1). Of note, the G742D mutation is very rare in cancers other than CLL. A separate recent exome sequencing study in uveal melanoma reported an unexpectedly high frequency of mutations (18.6% of 102 cases) occurring exclusively at codon 625 of the SF3B1 gene.15 Altogether, these observations demonstrate that mutations at different sites of SF3B1 can be differentially enriched depending on the specific cancer type, and suggest these mutations might have different functional impact on the respective diseases. For CLL, the striking positional clustering of SF3B1 mutations suggests that they are positively selected during CLL pathogenesis, and therefore are most likely driver mutations in CLL. Consistent with the distribution of affected cancers, SF3B1 is ubiquitously expressed, although at higher levels in cells from hematopoietic lineages (Figure 2A).16 Compared with normal B cells, CLL cells have increased SF3B1 expression (Figure 2B).3 DNA hypomethylation in the gene body of SF3B1 has been observed in CLL (Figure 2C),17 although it remains unclear whether this hypomethylation is related to the increased SF3B1 expression in CLL. Cases with mutated SF3B1 at the DNA level also have detectable expression of the mutated transcript at the mRNA level (Figure 2D).

Distribution of mutations in SF3B1. Mutations in SF3B1 predominantly localize to its C-terminal domain between the fifth and eighth HEAT repeats (exons 14-16). (A) The accumulated mutation sites and frequencies from 5 published CLL sequencing studies. (B) The mutation sites and frequencies reported from other types of cancers (retrieved from COSMIC [version 62]). Rare mutations outside of the fifth to eighth HEAT repeats are not shown.

Distribution of mutations in SF3B1. Mutations in SF3B1 predominantly localize to its C-terminal domain between the fifth and eighth HEAT repeats (exons 14-16). (A) The accumulated mutation sites and frequencies from 5 published CLL sequencing studies. (B) The mutation sites and frequencies reported from other types of cancers (retrieved from COSMIC [version 62]). Rare mutations outside of the fifth to eighth HEAT repeats are not shown.

SF3B1 expression and methylation in normal and CLL cells. (A) SF3B1 relative expression in different human tissues. (B) SF3B1 relative expression in normal B-cell subpopulations and CLL samples. CB, centroblast; CC, centrocyte. Data generated from Affymetrix HG-U133Plus2 arrays. (C) DNA methylation on SF3B1 in CLL samples with or without SF3B1 mutation and normal B cells. (D) Targeted pyrosequencing of a SF3B1 K700E site of cDNA from normal peripheral blood mononuclear cells (top, NL PBMC) compared with cDNA from a CLL sample with known K700E mutation in SF3B1 (bottom). K700E mutation is generated from an A2098G transition on the sense strand; this pyrosequencing assay was designed to detect the T to C transition at the corresponding site on the antisense strand. cDNA, complementary DNA. Panel A adapted from the Novartis Gene Atlas16 with permission. Panel B adapted from Rossi et al3 with permission. Panel C adapted from Kulis et al17 with permission.

SF3B1 expression and methylation in normal and CLL cells. (A) SF3B1 relative expression in different human tissues. (B) SF3B1 relative expression in normal B-cell subpopulations and CLL samples. CB, centroblast; CC, centrocyte. Data generated from Affymetrix HG-U133Plus2 arrays. (C) DNA methylation on SF3B1 in CLL samples with or without SF3B1 mutation and normal B cells. (D) Targeted pyrosequencing of a SF3B1 K700E site of cDNA from normal peripheral blood mononuclear cells (top, NL PBMC) compared with cDNA from a CLL sample with known K700E mutation in SF3B1 (bottom). K700E mutation is generated from an A2098G transition on the sense strand; this pyrosequencing assay was designed to detect the T to C transition at the corresponding site on the antisense strand. cDNA, complementary DNA. Panel A adapted from the Novartis Gene Atlas16 with permission. Panel B adapted from Rossi et al3 with permission. Panel C adapted from Kulis et al17 with permission.

SF3B1 mutation is associated with poorer clinical outcome

Two of the initial studies that reported associations with mutated SF3B1 and CLL were conducted using case cohorts that were heterogeneous with respect to their clinical characteristics, and which were collected at variable points in disease course.2,4 These studies found SF3B1 mutations to associate with poorer clinical outcome. Wang et al reported that SF3B1 mutation is significantly associated with an earlier time-to-treatment initiation,2 while Quesada et al observed associations with faster disease progression and shorter overall survival.4 Importantly, both studies found SF3B1 mutation to provide independent prognostic information from other known CLL prognostic markers, such as ZAP70 expression, IGHV mutational status, and cytogenetic aberrations.2,4 Rossi et al identified that SF3B1 mutations were associated with more advanced disease, as 17% of fludarabine-refractory cases had SF3B1 mutations, compared with 5% of cases at diagnosis.3

More recent studies have provided a consistent picture that SF3B1 mutation is associated with more aggressive disease and poorer clinical outcome (summarized in Table 1 and Table 22-7,10,11,18-23 ). Greco et al found that SF3B1 mutations were present in only 1.5% of individuals with the CLL precursor condition, monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis.18 Consistent with these reports, Mansouri et al examined 360 newly diagnosed Scandinavian patients, and identified only a small percentage of cases with mutated SF3B1 (3.6%).5 However, multivariate analysis revealed that those patients harboring SF3B1 mutation demonstrated significantly worse overall survival and earlier time to treatment. Independently, a large study of 1124 newly diagnosed CLL patients from the German CLL Study Group (GCLLSG) has confirmed that SF3B1 mutations associate with a shorter time to first therapy, and with unmutated IGHV status.6 An analysis of ∼500 cases from a prospective and controlled clinical trial (the UK LRF CLL4 trial) demonstrated a high rate of SF3B1 mutation (17%) in patients requiring frontline treatment, and that presence of mutation associated with significantly worse overall survival and with a trend toward shorter progression-free survival.7 Finally, a recent analysis of cases enrolled in the GCLLSG CLL8 trial, in which patients were randomized to firstline therapy with either the combination of fludarabine and cyclophosphamide alone or with rituximab demonstrated that while SF3B1 mutations did not impact response to therapy, they were associated with significantly lower progression-free survival and a trend toward inferior overall survival.8

Associations of SF3B1 mutation in patients with CLL and MDS

| Disease . | Initial discovery of association, reference . | Association with a disease subtype . | Further clinical associations . | Clonal status . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLL | 2 | del(11q)2,6 | • Shorter treatment-free or overall survival3,4,6,7,18 | Predominantly subclonal: likely a later event19 |

| 3 | • Faster disease progression2,4,5,18 | |||

| 4 | • Fludarabine refractoriness3 | |||

| MDS | 10 | Refractory anemia with ring sideroblasts10,11,20-22 | • Longer event-free or overall survival11,21-23 | Predominantly clonal: likely an earlier event21 |

| 11 | • Lower risk of evolution into AML21 |

| Disease . | Initial discovery of association, reference . | Association with a disease subtype . | Further clinical associations . | Clonal status . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLL | 2 | del(11q)2,6 | • Shorter treatment-free or overall survival3,4,6,7,18 | Predominantly subclonal: likely a later event19 |

| 3 | • Faster disease progression2,4,5,18 | |||

| 4 | • Fludarabine refractoriness3 | |||

| MDS | 10 | Refractory anemia with ring sideroblasts10,11,20-22 | • Longer event-free or overall survival11,21-23 | Predominantly clonal: likely an earlier event21 |

| 11 | • Lower risk of evolution into AML21 |

Taken together, these findings suggest that a molecular marker such as SF3B1 mutation can potentially help refine the existing framework for prognostication in CLL. The current gold standard uses common fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) cytogenetic abnormalities, and includes favorable cytogenetic abnormalities such as del(13q), and poorer features such as trisomy 12, del(11q), and del(17p).24 Recently, Rossi et al evaluated the potential of mutations in SF3B1, NOTCH1, and BIRC3 to more finely stratify patients into different risk groups beyond what could be achieved with FISH cytogenetics alone.25 In this integrated analysis of mutations and cytogenetics, patients with SF3B1 mutation and/or NOTCH1 mutation and/or del(11q) were classified into the intermediate-risk group with 37% 10-year survival. Although SF3B1 mutation does not confer the same degree of poor prognosis as TP53 mutation,7 these results overall demonstrate that SF3B1 mutation status can improve the accuracy of prediction of disease progression in combination with conventional biologic markers.25 Interestingly, a recent analysis shows that CLL patients with poor prognostic markers, such as SF3B1, TP53, and NOTCH1 mutation, do not show decreased 6-year survival after reduced-intensity allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), demonstrating these mutations do not have high impact on the long-term disease control of HSCT.26

SF3B1 and the temporal order of mutations in CLL

The genetic studies described above consistently demonstrate that mutated SF3B1 is associated with poor prognosis. We considered that the common cytogenetic abnormalities in CLL can often be present in only leukemia cell subpopulations and yet still hold prognostic significance. For example, up to 80% of CLL samples have detectable FISH abnormalities, and multiple FISH abnormalities often occur at varying frequencies within the same bulk sample, implying the coexistence of subclones harboring different chromosome-level changes. Acknowledgment of the existence of subpopulations harboring prognostically significant cytogenetic abnormalities raises the question of whether and how specific genetic alterations, including driving somatic mutations, such as SF3B1, that are present within subclones, can impact clinical course.

Recently, whole-genome sequencing and WES studies have provided the opportunity to address this question, as subpopulations can be detected and tracked at unprecedented resolution through identification and clustering of mutations with similar allelic frequencies.27,28 Using this approach, a striking degree of intratumoral heterogeneity has been detected across blood malignancies.29,30 In the case of CLL, Schuh et al performed whole-genome sequencing on sequential samples collected from 3 CLL cases over the course of years and following various treatments to investigate clonal evolution of somatic mutations in CLL. Their longitudinal analysis revealed that the clonal evolution patterns between individual patients are quite heterogeneous.31 Specifically, a remarkable equilibrium among leukemia subpopulations over the course of years, even in the presence of cytoreductive therapy, was observed in some cases, while acquisition of new mutations and change in the percentage of affected cells over time was observed in others. These data suggest that subclonal mutations expand over time as a function of their fitness-integrating intrinsic factors (eg, proliferation and apoptosis) and extrinsic pressures (eg, interclonal competition and therapy).32 In a separate analysis, Landau et al developed an analytic approach to enable the study of clonal evolution of CLL using WES data. In this study, WES and copy number data were integrated to estimate the fraction of cancer cells harboring each somatic mutation, and this approach was applied to study clonal evolution of somatic mutations in 149 CLL samples.19

Analysis of the clonal and subclonal mutations in this large CLL series by Landau et al revealed that SF3B1 is typically a subclonal mutation and hence likely a later event in the progression of CLL.19 This result was inferred by comparing the aggregate frequencies of recurrent driver mutations across this large series of cases. Focusing on a set of 24 CLL driver events that were derived by performing a significance analysis for frequent somatic single nucleotide variants and recurrent somatic copy number alterations, Landau et al inferred the fraction of cancer cells and the percentage of clonality of these driver events across 149 samples.19 As shown in Figure 3A,19 3 driver mutations (MYD88 [n = 12 samples], trisomy 12 [n = 24], and heterozygous del(13q) [n = 62]) were clonal in 80% to 100% of samples, a significantly higher level than for other driver events (q < 0.1), suggesting that they arise earlier in typical CLL development. Moreover, in CLL samples that harbored 1 of these 3 early driver mutations, additional driver alterations were found at either similar or lower cancer cell fraction (CCF) suggesting that the proposed order of events holds across individual patients, not only in aggregate. Other drivers (eg, ATM, TP53, and SF3B1) were often observed at subclonal frequencies, indicating that they often arise later in leukemic development. Analysis of co-occurrence of the 19 SF3B1 mutations within this cohort with other driver alterations revealed that SF3B1 was subclonal in 10 of 19 cases (53%). In 7 of 10 cases (70%), subclonal SF3B1 was present together with clonal del(13q), and in 3 of 10 cases (30%), with clonal del(11q) (Figure 3B). These data together suggest that mutations that selectively affect B cells may contribute more to the initiation of disease and precede selection of more generic cancer drivers that underlie disease progression.

SF3B1 mutation is a predominantly subclonal event in CLL. (A) Percentage of the mutations classified as clonal (orange) and subclonal (blue) for each putative CLL driver, within a cohort of 149 CLL cases. The number of cases (n) affected by each genetic alteration is shown (*Drivers with q value < 0.1 for a higher proportion of clonal mutations compared with the entire CLL drivers set). (B) Analysis of co-occurrence of the 19 SF3B1 mutations within 149 CLL cases with other driver alterations. Top bar shows the color representation of CCF. (C) Joint distributions of CCF values across 2 time points using clustering analysis (see Landau et al for method19 ). Red denotes a mutation that had an increase in CCF of >0.2 (with probability >0.5). The dotted diagonal line represents CCF values that were identical across the 2 time points. The dotted parallel lines denote the 0.2 CCF interval on either side. Panel A adapted from Landau et al19 with permission.

SF3B1 mutation is a predominantly subclonal event in CLL. (A) Percentage of the mutations classified as clonal (orange) and subclonal (blue) for each putative CLL driver, within a cohort of 149 CLL cases. The number of cases (n) affected by each genetic alteration is shown (*Drivers with q value < 0.1 for a higher proportion of clonal mutations compared with the entire CLL drivers set). (B) Analysis of co-occurrence of the 19 SF3B1 mutations within 149 CLL cases with other driver alterations. Top bar shows the color representation of CCF. (C) Joint distributions of CCF values across 2 time points using clustering analysis (see Landau et al for method19 ). Red denotes a mutation that had an increase in CCF of >0.2 (with probability >0.5). The dotted diagonal line represents CCF values that were identical across the 2 time points. The dotted parallel lines denote the 0.2 CCF interval on either side. Panel A adapted from Landau et al19 with permission.

Within this conceptual framework, SF3B1 mutations are mostly subclonal and these results suggest that SF3B1 mutations are not typically initiators of CLL, but rather promoters of disease progression. As such, it is likely that SF3B1 mutations cooperate with other mutations to affect CLL. Consistent with this framework, Landau et al assessed the evolution of somatic mutations in 18 patients, in which data from 2 distant time points were available.19 Clonal evolution was observed in 11 of 18 patients (10 of 12 who received intervening treatment, but only 1 of 6 without intervening treatment, P = .012) and confirmed that subclonal mutations (eg, del(11q), SF3B1 and TP53) shifted toward clonality over time (Figure 3C).

One notable observation by Landau et al from the analysis of these 18 longitudinally studied cases was that the presence of subclonal driver mutations (defined by CLL significance analysis19 or by mutations within highly conserved sites of genes within the Cancer Gene Census33 ) in the pretreatment sample appeared to be indicative of clonal evolution. Further analysis of the 149 patients revealed that presence of subclonal (but not clonal) driver mutations, such as SF3B1, was indeed associated with poorer clinical outcome, and was independent of confounding factors such as IGHV mutation status, the identity of driver mutations and presence of cytogenetic abnormalities.19 Thus, an important finding with potential clinical implications is that detection of subclonal (but not clonal) driver mutations such as SF3B1 marks ongoing clonal evolution, which is in turn associated with more aggressive disease in CLL.

Potential functional effects of SF3B1 mutations in CLL

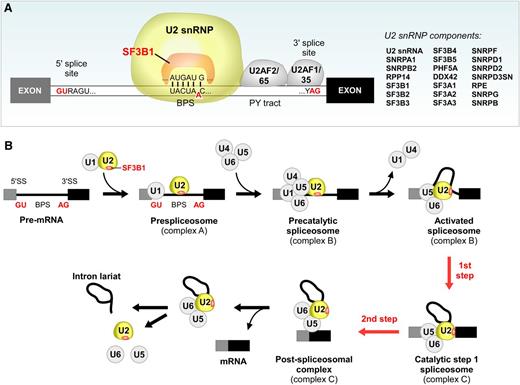

At present, it remains unclear how SF3B1 mutation impacts CLL at the cellular level. However, it is constructive to consider the known cellular functions of SF3B1, as these might offer important clues. SF3B1 is an essential component of U2 snRNP, which contains U2 small nuclear RNA and ∼20 proteins that associate in a highly organized complex. As shown in Figure 4A, SF3B1 directly interacts with both the 5′ and 3′ sides of the branch point sequence (BPS) (Figure 4A). In addition to the components within the U2 snRNP, SF3B1 also interacts with other proteins in the spliceosome. For instance, SF3B1 directly interacts with U2AF2, which binds to the polypyrimidine tract (PY tract) adjacent to the SF3B1 binding site.34,35 It has been suggested that such multiple interactions are crucial for the recognition and stabilization of the spliceosome at the 3′ splice sites.36 In fact, the formation of a duplex between the U2 small nulcear RNA and the BPS is an early step in the splicing pathway (Figure 4A), and results in the bulging of a conserved adenosine in the BPS. This adenosine is used as the nucleophile for the first catalytic step of the splicing reaction (Figure 4B).9 The rough structure of the C-terminal 22 HEAT repeats domain of SF3B1 has been characterized by single-particle electron cryomicroscopy techniques, and these studies suggest that the HEAT repeats region might undergo significant conformational change during the formation of the U2 snRNP complex37,38 Quesada et al constructed a tentative homology model of the C-terminal domain of SF3B1.4 According to this model, the mutation hot spots in SF3B1 seem to cluster at the inner surfaces of the structure, at the supposed sites of interaction with RNA and cofactors. These characterizations suggest that mutation in SF3B1 could possibly mediate alteration in its normal function through change in the physical interactions of SF3B1 with its binding partners.

SF3B1 is an essential component in U2 snRNP and crucial for RNA splicing. (A) SF3B1 lies within the U2 snRNP and interacts with the 5′ and 3′ adjacent sites of the BPS, a critical splice site motif. PY tract, polypyrimidine tract. (B) A schematic of the stepwise process of pre-mRNA splicing.

SF3B1 is an essential component in U2 snRNP and crucial for RNA splicing. (A) SF3B1 lies within the U2 snRNP and interacts with the 5′ and 3′ adjacent sites of the BPS, a critical splice site motif. PY tract, polypyrimidine tract. (B) A schematic of the stepwise process of pre-mRNA splicing.

Consistent with the critical role of SF3B1 in splicing, evidence of altered splicing has been detected in CLL cases with SF3B1 mutations. Wang et al reported intron retention in known target genes of spliceosome inhibition.2,39,40 Quesada et al compared splicing in CLL cases with and without mutated SF3B1 by exon arrays and RNA sequencing. They detected relatively few transcripts with altered splicing in CLL cases with mutated SF3B1, suggesting that the SF3B1 mutation does not exert a global effect on splicing, but rather only affects few specific target transcripts.4 Of note, the differential splice site usage identified by RNA sequencing found previously described 5′ splice sites but novel 3′ splice sites, consistent with the crucial function of SF3B1 in the interaction between the U2 snRNP and BPS, close to the 3′ splice site.4 One of the identified splicing variants associated with mutant SF3B1 affects the FOXP1 forkhead transcription factor, and expression of truncated FOXP1 variants has been implicated in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.41 This observation suggests that the splicing variants associated with SF3B1 mutation might affect factors involved in malignant transformation of B cells.

One hint of the potential impact of SF3B1 mutation on CLL comes from the observation that SF3B1 mutation significantly co-occurs with del(11q).2 As the minimal deleted region of 11q(del) contains the ATM gene, one intriguing possibility is that SF3B1 mutation could alter responses to DNA damage.2 In support of this idea, te Raa et al demonstrated that CLL samples with SF3B1 mutation show decreased expression of P53 target genes in response to irradiation, resembling CLL samples with ATM mutation or del(11q).42 Of note, a large unbiased small interfering RNA screen identified a group of splicing factors, including multiple components in U2 snRNP, as key factors involved in DNA damage response.43 These results implicate a general role of splicing in maintenance of genomic stability.

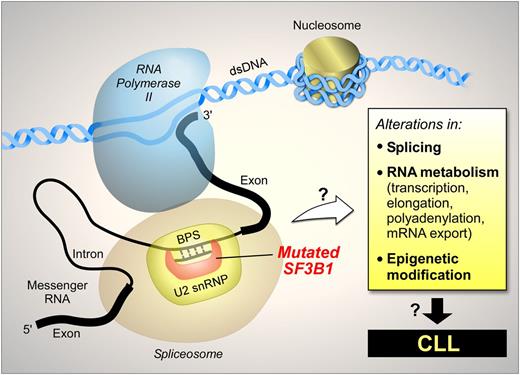

These observations suggest that SF3B1 mutation might have broader functions beyond RNA splicing alone. An open question is whether such effects are mediated through splicing variant intermediaries or other direct effects (schematically shown in Figure 5). For example, gene expression involves a highly complex network of interactions, and splicing is coupled with other steps in gene expression, such as transcription, capping, polyadenylation, and mRNA nuclear export.44 Thus, mutations in splicing factors, such as SF3B1, might affect gene expression through mechanisms other than splicing itself. Recently, Ramsay et al reported frequent somatic mutations in components of the RNA processing machinery in CLL, raising the question of whether disruption of not only splicing but also the entire RNA processing pathway might be involved in CLL.45

Finally, heterozygous Sf3b1 knockout mice show decreased interaction with the Polycomb protein Zfp144 and manifest defects in bone development concomitant with ecotopic expression of Hox genes. These associations suggest a potential role of SF3B1 in epigenetic modification.46 Recently, Kulis et al reported global DNA hypomethylation in CLL, and demonstrated a significant role of epigenetic alteration in the disease.17 It is conceivable that SF3B1 mutation might also lead to some epigenetic modifications, which impacts CLL, but this has yet to be fully demonstrated.

SF3B1 mutations in MDS

SF3B1 mutation in MDS has been extensively reviewed recently.47,48 In striking contrast to CLL, SF3B1 mutations in MDS are associated with favorable prognosis and appear to be mostly clonal events in MDS (Table 2). The basis of these differences between MDS and CLL are currently unknown. SF3B1 mutations are highly prevalent in a mild MDS variant with presence of ring sideroblasts. Visconte et al reported that bone marrow aspirates of Sf3b1 heterozygous knockout mice show ring sideroblasts, suggesting that SF3B1 haploinsufficiency leads to the formation of ring sideroblasts.49 Despite this finding, whether SF3B1 mutations cause loss of function in MDS remains unclear.

Conclusion

SF3B1 mutation is associated with rapid disease progression and shorter survival in CLL, which can be used as a prognosis marker to improve the prediction of disease progression. In CLL, SF3B1 mutations are mostly subclonal events, and therefore likely involved in disease progression. Dedicated efforts are now required to investigate the causative link between SF3B1 mutation and CLL pathogenesis. Mutated SF3B1 might be a good therapeutic target for the treatment of CLL if the underlying mechanism of the functional impact of SF3B1 in CLL can be clarified.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Robin Reed and Angela Brooks for critical reading of this manuscript. They also thank Peter Stojanov for analysis data.

Y.W. is supported by a fellowship from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society. C.J.W. acknowledges support from the Blavatnik Family Foundation, the Lymphoma Research Foundation, and the National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (1RO1HL103532-01, 1RO1HL116452-01) and National Cancer Institute (1R01CA155010-01A1), and is a recipient of a Leukemia Lymphoma Translational Research Program Award and an American Association of Cancer Research: Stand Up To Cancer Innovative Research Grant.

Authorship

Contribution: Y.W. and C.J.W. conceived the article and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Catherine J. Wu, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Harvard Institute of Medicine, Room 420, 77 Avenue Louis Pasteur, Boston, MA 02115; e-mail: cwu@partners.org.

![Figure 1. Distribution of mutations in SF3B1. Mutations in SF3B1 predominantly localize to its C-terminal domain between the fifth and eighth HEAT repeats (exons 14-16). (A) The accumulated mutation sites and frequencies from 5 published CLL sequencing studies. (B) The mutation sites and frequencies reported from other types of cancers (retrieved from COSMIC [version 62]). Rare mutations outside of the fifth to eighth HEAT repeats are not shown.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/121/23/10.1182_blood-2013-02-427641/4/m_4627f1.jpeg?Expires=1765891458&Signature=aFh3y5j5r6hnFiFy950mQUuCopaEOSshcxz5Us-Nu-2OPZSkH2WgaA39GycuK6BJqekRqAmQ~LT0Mz-wF~gu18Ft-qY0XR6wUi62Z-BvpoZ0DB9cVebbEB~fiorIvHkTsHSvCBox7gquUUjj5btOWWsvCrPQIn3ZCiznY~jQwDudCGTYvWuWXzlvCIjW3MdlDxVSfxMCb0R5DMoc7-j~~c00-nIQ3H-ZvtPbjlccTiHS4kcIfICbmv~yUUclz~LMS5wKIuiVcO8ewwDrT6d~sogq09BzCkY~LVsW5b8LOiVY9oPTD1ZIIDNsbQVVIXa195-j8ZUbMm1~axJteiNe~A__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)