Key Points

Therapeutic preparations of IVIg have high levels of HLA (Ia and Ib) reactivity. Anti–HLA-E mAbs mimicked IVIg HLA-I reactivity.

Anti–HLA-E mAbs might be useful in suppressing HLA antibody production similar to IVIg and in the way that anti-RhD Abs suppress production.

Abstract

The US Food and Drug Administration approved intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg), extracted from the plasma of thousands of blood donors, for removing HLA antibodies (Abs) in highly sensitized patients awaiting organ transplants. Since the blood of healthy individuals has HLA Abs, we tested different IVIg preparations for reactivity to HLA single antigen Luminex beads. All preparations showed high levels of HLA-Ia and -Ib reactivity. Since normal nonalloimmunized males have natural antibodies to the heavy chains (HCs) of HLA antigens, the preparations were then tested against iBeads coated only with intact HLA antigens. All IVIg preparations varied in level of antibody reactivity to intact HLA antigens. We raised monoclonal Abs against HLA-E that mimicked IVIg’s HLA-Ia and HLA-Ib reactivity but reacted only to HLA-I HCs. Inhibition experiments with synthetic peptides showed that HLA-E shares epitopes with HLA-Ia alleles. Importantly, depleting anti–HLA-E Abs from IVIg totally eliminated the HLA-Ia reactivity of IVIg. Since anti–HLA-E mAbs react with HLA-Ia, they might be useful in suppressing HLA antibody production, similar to the way anti-RhD Abs suppress production. At the same time, anti–HLA-E mAb, which reacts only to HLA-I HCs, is unlikely to produce transfusion-related acute lung injury, in contrast to antibodies reacting to intact-HLA.

Introduction

Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) is a pharmaceutical preparation of plasma-derived human immunoglobulin G (IgG). It is extracted from the plasma of 1000 to 60 000 blood donors and shown to be beneficial in the treatment of a variety of autoimmune and inflammatory conditions.1 The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved use of IVIg to treat Kawasaki disease (KD), immune-mediated thrombocytopenia, primary immunodeficiencies, hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (for those >20 years), chronic B-cell lymphocytic leukemia, and pediatric HIV type 1 infection. The following inflammatory conditions are also treated with IVIg: solid organ transplantation; hematological diseases; nephropathy; cancer; infection; autoimmune diseases; cardiomyopathy; lung, eye, and ear diseases; recurrent pregnancy loss; chronic fatigue syndrome; congenital heart block; and transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI).

In 2004, the FDA approved the Cedars–Sinai IVIg desensitization protocol for lowering allo-HLA antibodies (Abs) in patients waiting for kidney transplant so they can accept a kidney from any healthy living donor. Since that time, IVIg has emerged as a potential treatment strategy for desensitization protocols and also for lowering the incidence of donor-specific Abs (DSA) involved in Ab-mediated rejection (AMR). Several transplant centers2-8 have adopted the protocol of IVIg administration for patients awaiting transplantation and for allograft recipients in order to reduce allo-HLA Abs or DSA directed against the HLA of donor kidneys.

IVIg is plasma derived, human IgG pooled from thousands of donors. Consequently, it may contain HLA antibodies because several allo-HLA antibodies are known to occur naturally in the sera of both men (nonalloimmunized) and women.9-13 Morales–Buenrostro et al11 demonstrated the specificities and incidence of these allo-HLA-I Abs in nonalloimmunized males. Neither the origin nor cause of anti-HLA Abs occurring in healthy individuals has been established.

While examining the specificity of commercial mouse anti–HLA-E mAbs (MEM-E/02, MEM-E/06, MEM-E/07, MEM-E/08, and 3D12), it was noted that these mAbs reacted with microbeads, each coated with a single HLA-Ia molecule.14,15 The suggestion that the HLA-Ia reactivity of anti–HLA-E mAbs could be due to the peptide sequences shared between HLA-E and HLA class-Ia alleles14 was verified using synthetic peptides. The peptides inhibited both HLA-Ia and HLA-E reactivities of anti–HLA-E mAbs.14,15 These observations were extended to the sera of nonalloimmunized males to document that the observed HLA-Ia reactivity in human sera could be due to anti–HLA-E Abs.13 To ascertain whether immunizing humans with HLA-E would augment anti–HLA-E Abs with HLA-Ia reactivity, we examined sera of melanoma patients immunized with autologous melanoma cells grown in interferon-γ (IFN-γ), a cytokine known to induce overexpression of HLA-E.16-18 The immunized patients not only showed the augmentation of anti–HLA-E Abs, confirming the immunogenicity of HLA-E in humans, but also showed increased reactivity with HLA-Ia (single antigen) coated onto microbeads.18 Indeed, the pattern of HLA-Ia reactivity in immunized patients corresponded with the pattern of HLA-Ia reactivities exhibited by some of the anti–HLA-E mAbs. Furthermore, it was shown that anti–HLA-E Abs may account for the nondonor-specific anti–HLA-Ia Abs in renal and liver transplant recipients.19

Because IVIg derives from the pooled IgG Abs of multiple blood donors, it is hypothesized that IVIg may contain naturally occurring anti–HLA-E Abs that mimic anti–HLA-Ia Abs. In the present study, this hypothesis was tested by examining a therapeutic IVIg preparation for the presence of anti–HLA-E Abs and anti–HLA-Ia Abs reactivity before and after adsorbing out anti–HLA-E Abs from the preparation. In addition, mice immunized with 2 known alleles of human recombinant HLA-E alleles (HLA-ER107 and HLA-EG107) were examined to determine whether HLA-E mAbs mimic anti–HLA-Ia Abs in par with IVIg. The results confirmed that IVIg contains naturally occurring anti–HLA-E Abs that do mimic anti–HLA-Ia Abs.

Materials and methods

Sources and preparation of IgG

IVIg preparations from 4 sources were examined for anti–HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-Cw, HLA-E, HLA-F, and HLA-G Abs. The sources were (1) IVIg: GamaSTAN S/D (Talecris Biotherapeutics, Inc, Research Triangle Park, NC); (2) IVIg: Sandoglobulin (6 gr, lot 4305800026; CSL Behring, Kankakee, IL); (3) IVIg: Octagam (6 gr, lot A913A8431; Octapharma Pharmazeutika, Switzerland); and (4) IVIg: IVIGlob EX (VHB Life Sciences Limited, India). In addition, all preparations (except IVIGlob EX) and 2 lots of Gamunex-C (Talecris, 10%) were used at 1/2, 1/4, and 1/8 dilutions to test against regular beads (lot 7) and iBeads (lot 6). HLA-Ia alleles on regular beads may occur both as intact HLA with β2microglobulin (β2m) as well as heavy chains without β2m. The manufacturer of HLA beads (One Λ, Inc, Canoga Park, CA) recently generated beads with reduced amounts of β2m-free HLA, called iBeads. Differences in the reactivity of IVIg preparations to regular beads and iBeads may indicate whether IVIg binds more to intact HLA or to HLA heavy chains. All mAbs were also tested on iBeads. In addition, we used purified human IgG from Southern Biotech (cat. no. 0150-01, Birmingham, AL).

Sources of normal human sera

Sera from nonalloimmunized males, frozen and stored at the Terasaki Foundation Laboratory (TFL), were used. Informed consent was obtained from the healthy volunteers in Mexico and Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. IgG from some of the sera of normal nonalloimmunized males was purified using protein-G column as described earlier.19

Immunoassay with single-HLA antigen-coated microbeads

To detect IgG reactivity to HLA-E and HLA-Ia alleles in IVIg/purified human IgG/murine mAbs, multiplex Luminex-based immunoassay (One Λ, Inc) was used, as described elsewhere.13-15 IVIg and standard human IgG from commercial sources were serially diluted (from 1/2, ending in 1/256) with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.2) and added to the wells containing the antigen-coated microbeads. Anti–HLA-E mAbs were developed in-house (vide infra), and the supernatants collected from the hybridoma culture were used without dilution. Using dual-laser flow cytometry (Luminex xMAP multiplex technology), the single antigen assays were performed for data acquisition and analysis of anti–HLA-Ia and anti–HLA-E Abs.13-15 The LABScreen Single Antigen (One Λ) assay consists of a panel of color-coded microspheres (single antigen beads) coated with HLA antigens to identify antibody specificities. The single recombinant HLA-Ia antigens in LS1A04-lot 003, 004, and 005 were used for screening IVIg and human standard IgG. This lot contains 31 HLA-A, 50 HLA-B, and 16 HLA-Cw allelic molecules. The beads supplied by the manufacturer may have 2 categories of proteins attached to the beads: HLA heavy-chain polypeptide only and heavy-chain polypeptides in association with β2m. Realizing the heterogeneity of proteins, the manufacturer recently developed iBeads (provided as Felix beads for in-house experimental use), which are regular HLA-Ia antigen-coated microbeads subjected to proprietary enzymatic treatment to remove or reduce the amount of heavy chains (also referred to as “denatured antigens”) by the manufacturers. The recombinant HLA-E, HLA-F, and HLA-G folded heavy chains (10 mg/mL in 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid [MES] buffer) were obtained from the Immune Monitoring Laboratory, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (University of Washington, Seattle, WA). The recombinant HLA-E, HLA-F, and HLA-G heavy chains are individually attached by a process of simple chemical coupling to 5.6-μm polystyrene microspheres, which are internally dyed (by One Λ) with infrared fluorophores.13-15 The HLA-Ia microbeads have built-in control beads: positive beads that are coated with human IgG (or murine IgG when mAb was used) and negative beads that are coated with serum albumin (HSA/BSA). For HLA-E, HLA-F, and HLA-G, the control beads (both positive and negative) were added separately. Data generated with Luminex Multiplex flow cytometry (LABScan 100) were analyzed using the same computer software and protocols as reported earlier.13-15 For each analysis, at least 100 beads were counted. Mean and standard deviation (SD) of mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) for each allele were recorded. All data were stored and archived at TFL; basic statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel software.

Affinity chromatography

To determine whether the HLA-Ia reactivity of IVIg is due to the presence of HLA-E antibodies in IVIg, the recombinant HLA-E heavy-chain polypeptide (6 mg) was dialyzed overnight at 4°C against a sodium bicarbonate buffer (0.1M NaHCO3; pH 8.5) to remove urea and dithiothreitol. For conjugating HLA-E to Affi-Gel 10, Affi-Gel 10 was washed with distilled water and sodium bicarbonate buffer for 20 minutes. After removing the supernatant, HLA-E (6 mg) in 1 mL of buffer was mixed with 338 μL of the Affi-Gel 10 suspension. The mixture was kept on an inverting rotator in a refrigerator overnight. The tube was taken out and centrifuged at 600g for 5 minutes. The supernatant was recovered and the gel washed 3 times in distilled water and twice with a carbonate buffer. After removing the supernatant completely, 100 μL of IVIg (1/128 dilution) was added to the gel and mixed well. The HLA-E/Affi-Gel 10/IVIg (1/128 dilution) mixture was placed on an inverter for 1 hour. Meanwhile, 100 μL of 1/128-diluted IVIg was further serially diluted (1/128, 1/256, 1/512, and 1/1024, to a total volume of 50 μL). IVIg adsorbed to HLA-E gel (or control Affi-Gel 10 without HLA-E) was recovered and designated eluate 1a and eluate 1b. Eluate 1 was also serially diluted, as described above. Entire sets were tested against HLA-E beads and HLA-Ia beads. IVIg used for this experiment came from the same batch as the original; however, it had been stored in aliquots in the refrigerator for 6 months. Consequently, the IVIg used in the experiment had reduced potency in binding to HLA; however, it did bind 1/4 of the original. The MFI of anti–HLA-E reactivity was >18 000 but only 4500 for the stored aliquots.

Production of murine monoclonal antibodies against HLA-ER107and HLA-EG107

Essentially, murine monoclonal antibodies were produced following the guidelines in the report generated by the National Research Council’s Committee on Methods of Producing Monoclonal Antibodies.20 The recombinant polypeptides of HLA-ER107and HLA-EG107 (heavy-chain only; 10 mg/mL in MES buffer) were obtained from the Immune Monitoring Laboratory, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center. Each antigen was immunized in 2 mice. Only 1 fusion was done for HLA EG107. Fifty micrograms of the antigen in 100 μL of PBS (pH 7.4) was mixed with 100 μL of TiterMax (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) adjuvant before injection into the footpad and intraperitoneum of the mice. Three immunizations were given at about 12-day intervals, with an additional immunization after 12 days for mice receiving HLA-EG107. The clones were cultured in a medium containing RPMI 1640 w/l-glutamine and sodium bicarbonate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, cat. no. R8758), 15% fetal calf serum, 0.29 mg/mL l-glutamine/Penn-Strept (Gemini-Bio, MedSupply Partners, Atlanta, GA; cat. no. 400-110), and 1mM sodium pyruvate (Sigma; cat. no. S8636). Several clones were also grown using Hybridoma Fusion and Cloning Supplement (HFCS; Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN; cat. no. 11363735001). Isotypes of all the mAbs were characterized, and no IgM Abs were detected. All the culture supernatants were screened for IgG reacting to HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-Cw, HLA-F, HLA-F, and HLA-G using single antigen microbeads on a Luminex platform. MFI was determined for culture supernatants after diluting to 1/2. The MFI values were corrected against those obtained with negative control beads.

Results

Normal male and female sera showed both HLA class-Ia and -Ib reactivity

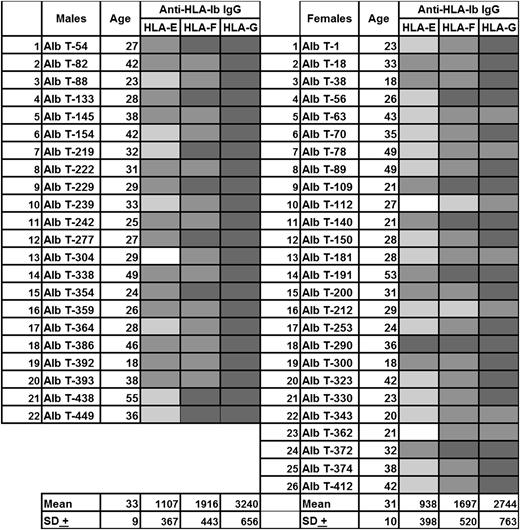

Sera of normal nonalloimmunized males and healthy females were examined for Abs reacting to HLA-E and HLA class-Ia (HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-Cw) alleles.13(Fig3) We noted that 66% of the sera with HLA-E IgG showed intense reactivity to several HLA-Ia alleles. The same sera of nonalloimmunized males that showed reactivity to HLA-E and HLA-Ia alleles also showed reactivity to all of the HLA-Ib alleles (HLA-E, HLA-F, and HLA-G; Figure 1). The difference in MFI of anti–HLA-E Abs could be due to differences in the microbeads or due to differences in the density of recombinant HLA-E used to conjugate onto the beads. Notably, the sera with HLA-E Abs and HLA-Ia reactivity also reacted with HLA-F and HLA-G. Such reactivity could be due either to individual Abs reacting with these alleles (HLA-Ia or -Ib) or to the possibility that anti–HLA-E IgG per se may react with all other HLA-I alleles.

Anti–HLA-Ib antibody reactivity (expressed as MFI) in the sera of normal nonalloimmunized males and healthy females. These sera were obtained from normal volunteers from Mexico. The sera are identified with Alb numbers. The corresponding HLA-Ia reactivity for the sera of nonalloimmunized males was reported elsewhere.9(Fig3) White box, MFI <500; light gray box, MFI 500-999; medium gray box, MFI 1000-1999; dark gray box, MFI 2000-4999.

Anti–HLA-Ib antibody reactivity (expressed as MFI) in the sera of normal nonalloimmunized males and healthy females. These sera were obtained from normal volunteers from Mexico. The sera are identified with Alb numbers. The corresponding HLA-Ia reactivity for the sera of nonalloimmunized males was reported elsewhere.9(Fig3) White box, MFI <500; light gray box, MFI 500-999; medium gray box, MFI 1000-1999; dark gray box, MFI 2000-4999.

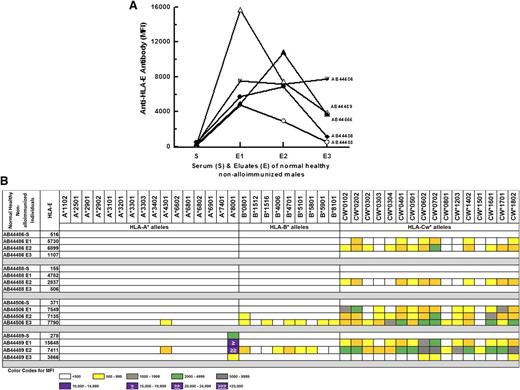

IgG purified from sera of normal males—negative for HLA-E or HLA-Ia alleles—showed anti–HLA-E reactivity concomitant with HLA-Ia reactivity

Earlier,13 we noted that 70% of sera that did not contain HLA-E Abs showed no reactivity to HLA-Ia alleles. To verify whether the presence of HLA-E Abs is revealed after purifying the sera, sera of 5 normal, healthy nonalloimmunized volunteers in Saudi Arabia were purified using protein-G columns. Three eluates were collected from each serum. The 5 sera were examined for Abs reacting to HLA-E, HLA-F, and HLA-G. Figure 2A shows that all 3 eluates of all 5 sera, which had very few or no anti–HLA-E Abs, showed the presence of anti–HLA-E IgG. Figure 2B shows that all 3 eluates of the 4 sera that had no reactivity to HLA-Ia alleles not only contained anti–HLA-E IgGs but also possessed HLA-Ia reactivity. The sera per se had highly restricted reactivity (AB44489) or no reactivity (AB44486, AB44488, AB44506) to HLA-Ia alleles. The IgG purified from 2 of the 4 sera (AB44486, AA44488) showed Cw-allele–restricted reactivity. These observations document that even those sera showing no detectable anti–HLA-E Abs or HLA-Ia reactivity contained both anti–HLA-E IgG and HLA-Ia reactivity upon purification. The alleles of HLA-Ia exhibiting reactivity to protein-G–purified human sera are strikingly similar—reactivity to the high-incidence HLA-Ia reactivity observed in normal human sera and anti–HLA-E mAb MEM-E/02.14 This suggests that anti–HLA-E IgG in the protein-G–purified normal human sera may mimic HLA-Ia reactivity.

HLA-E reactivity of IgG purified from the sera of normal nonalloimmunized males negative for anti–HLA-E Abs. These sera were obtained from normal volunteers from Saudi Arabia. The sera are identified with AB numbers. The purified IgG showed HLA-E reactivity (A) and reactivity for a variety of HLA-Ia alleles (B). MFI color code appears below data (B). This same color code can be used to assess MFI values in Figures 4 and 7.

HLA-E reactivity of IgG purified from the sera of normal nonalloimmunized males negative for anti–HLA-E Abs. These sera were obtained from normal volunteers from Saudi Arabia. The sera are identified with AB numbers. The purified IgG showed HLA-E reactivity (A) and reactivity for a variety of HLA-Ia alleles (B). MFI color code appears below data (B). This same color code can be used to assess MFI values in Figures 4 and 7.

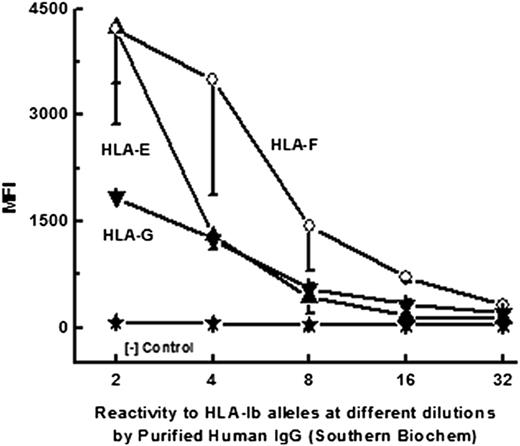

Purified human IgG reactive to HLA-E also showed HLA-Ia reactivity

Purified human IgG is available commercially and is a standard for immunoassays. Often, these commercial preparations are made from sera of 4 or 5 normal and healthy volunteers. One such preparation, obtained from Southern Biotek (Birmingham, AL), was examined to verify whether it contained both anti–HLA-E Abs and anti–HLA-Ia reactivity, as in protein-G–purified human sera. Figure 3 shows that the IgG purified from the sera of normal nonalloimmunized males reacts to HLA-Ia alleles (to avoid alloimmunized individuals, female sera were not used). Earlier13 we reported that anti–HLA-I Abs in females react to HLA-E, HLA-F, and HLA-G at different dilutions, with higher affinity for HLA-E. Table 1 shows reactivity of the purified IgG to HLA-B (HLA-B*3701) and 6 other HLA-Cw alleles (Cw*0202, Cw*0501, Cw*0602, Cw*0702, Cw*1601, and Cw*1802). The alleles of HLA-Ia exhibiting reactivity to the purified human IgG are strikingly similar in reactivity to the high incidence of HLA-Ia reactivity observed in normal human sera and by anti–HLA-E mAb MEM-E/02.14

Dosimetric profile of purified human IgG reactivity of HLA-Ib (HLA-E, HLA-F, and HLA-G) alleles.

Dosimetric profile of purified human IgG reactivity of HLA-Ib (HLA-E, HLA-F, and HLA-G) alleles.

HLA-Ia reactivity in purified human IgG from a commercial source

| . | Dilution . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | 1/2 (n = 3) . | 1/4 (n = 3) . | 1/8 (n = 3) . | |||

| HLA-la allele . | Mean . | SD . | Mean . | SD . | Mean . | SD . |

| B*3701 | 857 | 218 | 361 | 124 | 117 | 9 |

| CW*0202 | 1193 | 405 | 556 | 208 | 259 | 197 |

| CW*0501 | 1812 | 885 | 422 | 78 | 142 | 18 |

| CW*0602 | 2226 | 753 | 415 | 103 | 171 | 26 |

| CW*0702 | 3811 | 1101 | 3321 | 1283 | 904 | 133 |

| CW*1701 | 677 | 67 | 326 | 34 | 149 | 25 |

| CW*1802 | 1094 | 368 | 545 | 240 | 192 | 67 |

| . | Dilution . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | 1/2 (n = 3) . | 1/4 (n = 3) . | 1/8 (n = 3) . | |||

| HLA-la allele . | Mean . | SD . | Mean . | SD . | Mean . | SD . |

| B*3701 | 857 | 218 | 361 | 124 | 117 | 9 |

| CW*0202 | 1193 | 405 | 556 | 208 | 259 | 197 |

| CW*0501 | 1812 | 885 | 422 | 78 | 142 | 18 |

| CW*0602 | 2226 | 753 | 415 | 103 | 171 | 26 |

| CW*0702 | 3811 | 1101 | 3321 | 1283 | 904 | 133 |

| CW*1701 | 677 | 67 | 326 | 34 | 149 | 25 |

| CW*1802 | 1094 | 368 | 545 | 240 | 192 | 67 |

Human purified IgG from Southern Biochem.

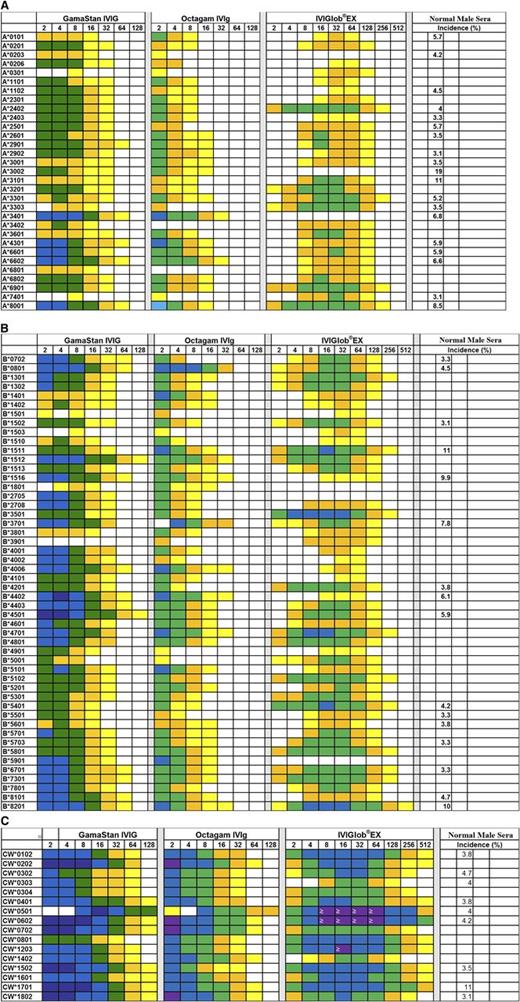

Anti–HLA-Ia and anti–HLA-Ib of IVIg

All 4 IVIg preparations showed a wide variety of reactivity to classic HLA-Ia (HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-Cw) coated on microbeads. The 4 IVIg preparations were serially diluted from 2 to 1024 with PBS and tested against single-antigen–coated microbeads containing 31 allelic proteins of HLA-A, 50 proteins of HLA-B alleles, and 16 proteins of HLA-C. The MFI values obtained for different HLA alleles at each dilution of IVIg were corrected against the corresponding MFI obtained with albumin-coated negative control beads. Table 2 shows that all the IVIg preparations reacted with several alleles of HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-Cw. GamaSTAN recognized the highest number of alleles in each category. Figure 4 illustrates dosimetric variations in the HLA-Ia allelic recognition of the 3 preparations of IVIg. Essentially, all IVIg preparations showed stronger reactivity to Cw alleles, followed by B alleles and then A alleles. IVIg reacted with all 16 Cw alleles tested. Comparing the preparations shown in Figure 4, it may be noted that the highest reactivity was observed with Cw*0102, Cw*0501, Cw*0602, Cw*0801, Cw*1502, Cw*1601, Cw*1601, and Cw1802. The Cw* reactivity of IVIg is comparable to the high incidence of HLA-Ia reactivities found in normal sera.11 IVIg reacted with several B* alleles, and high reactivity was observed with B*8201, B*1512, and B*4501. The high reactivity of IVIg observed with several B* alleles is also comparable to the incidence of HLA-B reactivity of normal nonalloimmunized male sera.11 IVIg also reacted strongly with a few A* alleles, including A*8001, A*3401, A*4301, A*6601, and A*6602. Interestingly, the high reactivity of IVIg with these A* alleles is strikingly similar to the high incidence of HLA-A reactivity observed with normal male sera.13

Dosimetric profile of HLA-Ia reactivity of IVIg from 3 Preparations. IVIg was diluted up to 1/512 and MFI was measured at all dilutions. Illustration of dosimetric HLA-A (A), HLA-B (B), and HLA-Cw (C) allelic reactivities of IVIg preparations. Percentage incidence of normal male sera is based on our earlier report.11

Dosimetric profile of HLA-Ia reactivity of IVIg from 3 Preparations. IVIg was diluted up to 1/512 and MFI was measured at all dilutions. Illustration of dosimetric HLA-A (A), HLA-B (B), and HLA-Cw (C) allelic reactivities of IVIg preparations. Percentage incidence of normal male sera is based on our earlier report.11

Number of HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-Cw alleles together with HLA-Ib alleles recognized by IVIg from different sources

| IVIg source . | Reactivity to different HLA-class Ia and Ib antigens . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of HLA-Ia alleles reactive to IVIg . | IVIg reactive HLA-Ib antigens . | |||||

| A . | B . | Cw . | E . | F . | G . | |

| GamaSTAN | 31 | 50 | 16 | + | + | + |

| Octagam | 30 | 47 | 16 | + | + | + |

| Sandoglobulin | 30 | 47 | 16 | + | + | + |

| GlobEX | 20 | 39 | 16 | + | + | + |

| IVIg source . | Reactivity to different HLA-class Ia and Ib antigens . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of HLA-Ia alleles reactive to IVIg . | IVIg reactive HLA-Ib antigens . | |||||

| A . | B . | Cw . | E . | F . | G . | |

| GamaSTAN | 31 | 50 | 16 | + | + | + |

| Octagam | 30 | 47 | 16 | + | + | + |

| Sandoglobulin | 30 | 47 | 16 | + | + | + |

| GlobEX | 20 | 39 | 16 | + | + | + |

The most noteworthy finding is that all IVIg preparations recognize most of the HLA class-Ia alleles and all HLA-Ib molecules, namely, HLA-E, HLA-F, and HLA-G. All preparations reacted with all 16 beads coated with HLA-Cw alleles. Such uniform recognition is not seen with other HLA-Ia alleles. All preparations of IVIg contained antibody reacting to HLA-E, HLA-F, and HLA-G.

HLA-Ia alleles on regular beads may occur as intact HLA with β2m as well as heavy chains without β2m, whereas on iBeads, they may occur as intact HLA with much reduced heavy chains. Table 3 shows that the different therapeutic preparations of IVIg differ in their reactivity to intact (regular beads) and heavy-chain HLA (iBeads). Octagam IVIg showed markedly decreased or reduced affinity for iBeads, suggesting its specific affinity for the heavy chains of all HLA-Ia alleles. Following Octagam, 1 lot of Gamunex (NKLK1, from Cedars–Sinai) showed a similar decreased affinity for iBeads, whereas the other lot of Gamunex (NKLG1) showed a notable increase in MFI with iBeads that was strikingly similar to that of Sandoglobulin and GamaSTAN. All IVIg preparations showed a marked increase in MFI for HLA-A and -B alleles, suggesting that these preparations bind to intact HLA-A and -B alleles. The decrease in MIF for IVIg preparations for HLA-Cw* alleles suggests that therapeutic IVIg preparations bind to heavy chains of HLA-C alleles. All of the anti–HLA-E mAbs poorly or minimally reacted with iBeads (data not shown), suggesting that the anti–HLA-E mAbs bind primarily to heavy chains of HLA.

Difference in MFI value and percentage of HLA-Ia reactivity of therapeutic IVIg preparations between regular beads and iBeads (reduced amount of heavy chain) coated with HLA-A (A), HLA-B (B), and HLA-Cw (C)

| Antigen . | Sandaglobulin . | Gamunex-C . | GamaSTAN . | Octagam . | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lot NKLG1 . | . | Lot NKLK1 . | |||||||||||||

| Regular, lot 7 . | iBead, lot 6 . | Difference . | Regular, lot 7 . | iBead, lot 6 . | Difference . | Regular, lot 7 . | iBead, lot 6 . | Difference . | Regular, lot 7 . | iBead, lot 6 . | Difference . | Regular, lot 7 . | iBead, lot 6 . | Difference . | |

| (1:4) . | (1:4) . | % . | (1:8) . | (1:8) . | % . | (1:8) . | (1:8) . | % . | (1:8) . | (1:8) . | % . | (1:8) . | (1:8) . | % . | |

| A. | |||||||||||||||

| Album in–NC | 1196 | 667 | –44 | 10753 | 7147 | –34 | 10268 | 7799 | –24 | 3793 | 5034 | 33 | 2340 | 1673 | –29 |

| A*0101(A1) | 0 | 551 | 100 | 368 | 3589 | 875 | 0 | 1355 | 100 | 0 | 809 | 100 | 260 | 262 | 1 |

| A*0201(A2) | 8 | 772 | 9550 | 0 | 4976 | 100 | 0 | 1989 | 100 | 659 | 2215 | 236 | 0 | 1002 | 100 |

| A*0203(A2) | 0 | 354 | 100 | 0 | 2975 | 100 | 233 | 648 | 178 | 24 | 328 | 1258 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| A*0206(A2) | 125 | 799 | 539 | 445 | 4409 | 891 | 913 | 2303 | 152 | 471 | 3061 | 550 | 780 | 1330 | 71 |

| A*0301(A3) | 2 | 199 | 9850 | 0 | 2839 | 100 | 410 | –211 | –151 | 236 | 0 | –100 | 515 | 0 | –100 |

| A*1101(A11) | 187 | 439 | 135 | 2535 | 3763 | 48 | 1942 | 1301 | –33 | 1073 | 1226 | 14 | 1556 | 351 | –77 |

| A*1102(A11) | 115 | 475 | 313 | 824 | 2861 | 247 | 529 | 858 | 62 | 1089 | 1859 | 71 | 829 | 46 | –94 |

| A*2301(A23) | 373 | 667 | 79 | 1775 | 3567 | 101 | 1125 | 1338 | 19 | 1877 | 1178 | –37 | 1417 | 576 | –59 |

| A*2402(A24) | 567 | 725 | 28 | 3171 | 4513 | 42 | 2352 | 2090 | –11 | 2312 | 2218 | –4 | 3071 | 663 | –78 |

| A*2403(A24) | 366 | 593 | 62 | 2701 | 3977 | 47 | 2049 | 1668 | –19 | 2297 | 1462 | –36 | 2868 | 443 | –85 |

| A*2501(A25) | 143 | 581 | 306 | 506 | 2975 | 488 | 488 | 408 | –16 | 1436 | 1905 | 33 | 790 | 58 | –93 |

| A*2601(A26) | 188 | 638 | 239 | 1732 | 4418 | 155 | 1116 | 1560 | 40 | 1004 | 1565 | 56 | 1169 | 402 | –66 |

| A*2901(A29) | 275 | 916 | 233 | 1243 | 4562 | 267 | 634 | 1418 | 124 | 897 | 3265 | 264 | 1046 | 1172 | 12 |

| A*2902(A29) | 200 | 932 | 366 | 1751 | 6014 | 243 | 820 | 2892 | 253 | 991 | 4433 | 348 | 1578 | 2268 | 44 |

| A*3001(A30) | 222 | 540 | 143 | 2107 | 4466 | 112 | 1230 | 1339 | 9 | 924 | 624 | –32 | 928 | 510 | –45 |

| A*3002(A30) | 174 | 526 | 202 | 896 | 3705 | 314 | 562 | 1412 | 151 | 1050 | 929 | –11 | 533 | 369 | –31 |

| A*3101(A31) | 0 | 295 | 100 | 166 | 3411 | 1955 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 121 | 351 | 189 | 366 | 0 | –100 |

| A*3201(A32) | 255 | 769 | 202 | 875 | 3764 | 330 | 424 | 915 | 116 | 856 | 1821 | 113 | 738 | 518 | –30 |

| A*3301(A33) | 185 | 684 | 270 | 1694 | 4462 | 163 | 925 | 1315 | 42 | 1119 | 1877 | 68 | 1494 | 1358 | –9 |

| A*3303 (A33) | 0 | 439 | 100 | 476 | 3329 | 599 | 179 | 517 | 189 | 322 | 725 | 125 | 542 | 152 | –72 |

| A*3401(A34) | 640 | 1150 | 80 | 3543 | 5215 | 47 | 2149 | 3415 | 59 | 3042 | 4323 | 42 | 2879 | 2059 | –28 |

| A*3402(A34) | 0 | 177 | 100 | 0 | 2053 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 684 | 1206 | 76 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| A*3601(A36) | 51 | 636 | 1147 | 916 | 3949 | 331 | 704 | 1551 | 120 | 564 | 1379 | 145 | 778 | 572 | –26 |

| A*4301(A43) | 397 | 949 | 139 | 1961 | 5601 | 186 | 1170 | 2719 | 132 | 1913 | 4182 | 119 | 1898 | 1693 | –11 |

| A*6601(A66) | 93 | 783 | 742 | 648 | 5328 | 722 | 875 | 2331 | 166 | 1408 | 2613 | 86 | 1695 | 1019 | –40 |

| A*6602(A66) | 364 | 768 | 111 | 1101 | 5194 | 372 | 838 | 1863 | 122 | 2362 | 4316 | 83 | 3650 | 684 | –81 |

| A*6801(A68) | 0 | 307 | 100 | 0 | 3148 | 100 | 0 | 662 | 0 | 192 | 634 | 230 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| A*6802(A68) | 455 | 596 | 31 | 1421 | 4662 | 228 | 1332 | 1948 | 46 | 2060 | 2084 | 1 | 1748 | 489 | –72 |

| A*6901(A69) | 470 | 788 | 68 | 2813 | 6243 | 122 | 2777 | 2885 | 4 | 1877 | 2410 | 28 | 1724 | 814 | –53 |

| A*7401(A74) | 0 | 316 | 100 | 666 | 3904 | 486 | 224 | 515 | 130 | 80 | 431 | 437 | 201 | 82 | –59 |

| A*8001(A80) | 401 | 564 | 41 | 3194 | 3969 | 24 | 1679 | 1188 | –29 | 2705 | 2847 | 5 | 2289 | 845 | –63 |

| B. | |||||||||||||||

| Albumin NC | 1196 | 667 | –44 | 10753 | 7147 | –34 | 10268 | 7799 | –24 | 3793 | 5034 | 33 | 2340 | 1673 | –29 |

| B*0702(B7) | 309 | 436 | 41 | 1539 | 2134 | 39 | 837 | 0 | –100 | 2223 | 2010 | –10 | 714 | 0 | –100 |

| B*0801(B8) | 233 | 274 | 18 | 2186 | 1511 | –31 | 1755 | 0 | –100 | 884 | 324 | –63 | 2119 | 114 | –95 |

| B*1301(B13) | 524 | 504 | –4 | 5168 | 3565 | –31 | 3522 | 1031 | –71 | 2244 | 1836 | –18 | 3679 | 52 | –99 |

| B*1302(B13) | 476 | 502 | 5 | 3103 | 1709 | –45 | 2532 | 0 | –100 | 2222 | 1199 | –46 | 1943 | 0 | –100 |

| B*1401(B64) | 621 | 206 | –67 | 3133 | 2100 | –33 | 2276 | 410 | –82 | 1749 | 269 | –85 | 2397 | 102 | –96 |

| B*1402(B65) | 239 | 152 | –36 | 2249 | 929 | –59 | 1441 | 0 | –100 | 670 | 0 | –100 | 1458 | 0 | –100 |

| B*1501(B62) | 0 | 148 | 100 | 0 | 749 | 100 | 15 | 53 | 253 | 106 | 394 | 270 | 100 | 0 | –100 |

| B*1502(B75) | 157 | 245 | 56 | 1525 | 2008 | 32 | 1536 | 91 | –94 | 526 | 709 | 35 | 861 | 0 | –100 |

| B*1503(B72) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2375 | 507 | –79 | 2296 | 0 | –100 | 689 | 0 | –100 | 1057 | 0 | –100 |

| B*1510(B71) | 240 | 271 | 13 | 1434 | 1452 | 1 | 1622 | 347 | –79 | 857 | 492 | –43 | 1293 | 0 | –100 |

| B*1511(B75) | 637 | 552 | –13 | 4058 | 3380 | –17 | 3825 | 1860 | –51 | 2822 | 2380 | –16 | 3640 | 1087 | –70 |

| B*1512(B76) | 382 | 1141 | 199 | 816 | 2811 | 244 | 942 | 1418 | 51 | 2655 | 5973 | 125 | 1129 | 1385 | 23 |

| B*1513(B77) | 550 | 445 | –19 | 4274 | 2353 | –45 | 3211 | 841 | –74 | 1238 | 904 | –27 | 2257 | 256 | –89 |

| B*1516(B63) | 799 | 756 | –5 | 3755 | 2400 | –36 | 3133 | 1212 | –61 | 3536 | 3285 | –7 | 3132 | 880 | –72 |

| B*1801(B18) | 0 | 114 | 100 | 538 | 1142 | 112 | 567 | 0 | –100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 246 | 0 | –100 |

| B*2705(B27) | 141 | 377 | 167 | 388 | 1657 | 327 | 160 | 0 | –100 | 1366 | 1085 | –21 | 154 | 0 | –100 |

| B*2708(B27) | 13 | 302 | 2223 | 0 | 1344 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1067 | 1407 | 32 | 54 | 0 | –100 |

| B*3501(B35) | 243 | 352 | 45 | 1672 | 1614 | –3 | 1478 | 577 | –61 | 680 | 653 | –4 | 964 | 0 | –100 |

| B*3701(B37) | 1099 | 740 | –33 | 6133 | 3639 | –41 | 4788 | 612 | –87 | 3236 | 392 | –88 | 9974 | 0 | –100 |

| B*3801(B38) | 254 | 248 | –2 | 1356 | 1375 | 1 | 1259 | 0 | –100 | 619 | 0 | 100 | 1002 | 0 | –100 |

| B*3901(B39) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 242 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| B*4001(B60) | 237 | 409 | 73 | 1677 | 2474 | 48 | 1240 | 93 | –93 | 1723 | 2286 | 33 | 987 | 4 | –100 |

| B*4002(B61) | 134 | 242 | 81 | 569 | 1679 | 195 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1564 | 1188 | –24 | 271 | 0 | –100 |

| B*4006(B61) | 765 | 359 | –53 | 5394 | 2144 | –60 | 4341 | 421 | –90 | 3470 | 2373 | –32 | 4972 | 167 | –97 |

| B*4101(B41) | 32 | 182 | 469 | 716 | 1486 | 108 | 605 | 0 | –100 | 1067 | 870 | –19 | 393 | 0 | –100 |

| B*4201(B42) | 0 | 86 | 100 | 455 | 1088 | 139 | 13 | 0 | –100 | 598 | 286 | –52 | 364 | 0 | –100 |

| B*4402(B44) | 683 | 461 | –33 | 6465 | 1869 | –71 | 5313 | 786 | –85 | 4301 | 3376 | –22 | 3997 | 702 | –82 |

| B*4403(B44) | 284 | 413 | 45 | 1110 | 2395 | 116 | 1213 | 836 | –31 | 3391 | 2904 | –14 | 1146 | 698 | –39 |

| B*4501(B45) | 272 | 612 | 125 | 1106 | 2110 | 91 | 562 | 399 | –29 | 3667 | 5397 | 47 | 956 | 308 | –68 |

| B*4601(B46) | 537 | 473 | –12 | 3014 | 3537 | 17 | 2450 | 851 | –65 | 1834 | 1460 | –20 | 2438 | 526 | –78 |

| B*4701(B47) | 355 | 655 | 85 | 2554 | 2799 | 10 | 2031 | 1235 | –39 | 1771 | 3211 | 81 | 2200 | 955 | –57 |

| B*4801(B48) | 297 | 341 | 15 | 3280 | 3131 | –5 | 1984 | 757 | –62 | 2252 | 1694 | –25 | 1863 | 104 | –94 |

| B*4901(B49) | 356 | 630 | 77 | 1586 | 1419 | –11 | 1881 | 158 | –92 | 1640 | 446 | –73 | 1340 | 0 | –100 |

| B*5001(B50) | 72 | 198 | 175 | 789 | 968 | 23 | 814 | 0 | –100 | 627 | 176 | –72 | 505 | 0 | –100 |

| B*5101(B51) | 669 | 687 | 3 | 3370 | 2343 | –30 | 2798 | 1101 | –61 | 1662 | 1336 | –20 | 1896 | 339 | –82 |

| B*5102(B51) | 688 | 604 | –12 | 2599 | 1898 | –27 | 2699 | 694 | –74 | 1677 | 476 | –72 | 1671 | 0 | –100 |

| B*5201(B52) | 707 | 869 | 23 | 3207 | 2125 | –34 | 2745 | 1224 | –55 | 1788 | 1341 | –25 | 1962 | 280 | –86 |

| B*5301(B53) | 692 | 536 | –23 | 3265 | 2368 | –27 | 4078 | 678 | –83 | 2040 | 478 | –77 | 2561 | 0 | –100 |

| B*5401(B54) | 299 | 168 | –44 | 2623 | 1463 | –44 | 1455 | 0 | –100 | 1633 | 476 | –71 | 2238 | 0 | –100 |

| B*5501(B55) | 222 | 44 | –80 | 3308 | 1072 | –68 | 1753 | 0 | –100 | 1558 | 686 | –56 | 1874 | 0 | –100 |

| B*5601(B56) | 507 | 183 | –64 | 2689 | 1269 | –53 | 2222 | 0 | –100 | 1995 | 0 | –100 | 1607 | 0 | –100 |

| B*5701(B57) | 419 | 560 | 34 | 1045 | 1987 | 90 | 942 | 286 | –70 | 1101 | 542 | –51 | 957 | 3 | –100 |

| B*5703(B57) | 897 | 382 | –57 | 2710 | 1620 | –40 | 2983 | 0 | –100 | 2148 | 0 | –100 | 2425 | 0 | –100 |

| B*5801(B58) | 726 | 455 | –37 | 4435 | 1829 | –59 | 3479 | 662 | –81 | 2758 | 106 | –96 | 3157 | 0 | –100 |

| B*5901(B59) | 502 | 446 | –11 | 3855 | 2216 | –43 | 3052 | 720 | –76 | 1798 | 1058 | –41 | 2444 | 470 | –81 |

| B*6701(B67) | 225 | 362 | 61 | 64 | 1113 | 1639 | –237 | –569 | 140 | 1108 | 603 | –46 | 841 | 0 | –100 |

| B*7301(B73) | 243 | 572 | 135 | 1817 | 3226 | 78 | 1945 | 1022 | –47 | 1755 | 3145 | 79 | 1740 | 1118 | –36 |

| B*7801(B78) | 446 | 556 | 25 | 2491 | 1568 | –37 | 2410 | 260 | –89 | 1737 | 283 | –84 | 1786 | 0 | –100 |

| B*8101(B81) | 364 | 550 | 51 | 2969 | 3082 | 4 | 1848 | 1096 | –41 | 2541 | 2799 | 10 | 1323 | 372 | –72 |

| B*8201(B82) | 639 | 360 | –44 | 6055 | 2731 | –55 | 4783 | –193 | –104 | 3857 | 4259 | 10 | 5026 | 510 | –90 |

| C. | |||||||||||||||

| Albumin NC | 1196 | 667 | –44 | 10753 | 7147 | –34 | 10268 | 7799 | −24 | 3793 | 5034 | 33 | 2340 | 1673 | –29 |

| CW*0102(Cw1) | 998 | 511 | –49 | 5361 | 5231 | –2 | 4314 | 1058 | −75 | 4538 | 2828 | –38 | 7724 | 1778 | –77 |

| CW*0202(Cw2) | 1275 | 719 | –44 | 7890 | 5379 | –32 | 6814 | 2800 | −59 | 7183 | 8101 | 13 | 9379 | 1840 | –80 |

| CW*0302(Cw10) | 1024 | 522 | –49 | 4952 | 4874 | –2 | 4130 | 1769 | −57 | 4010 | 2378 | –41 | 5608 | 1170 | –79 |

| CW*0303(Cw9) | 703 | 500 | –29 | 4262 | 4286 | 1 | 3017 | 1665 | −45 | 2855 | 2607 | –9 | 3350 | 1220 | –64 |

| CW*0304(Cw10) | 844 | 520 | –38 | 5758 | 4141 | –28 | 4429 | 1816 | −59 | 3713 | 2748 | –26 | 5552 | 1435 | –74 |

| CW*0401(Cw4) | 1569 | 601 | –62 | 7529 | 3726 | –51 | 6484 | 1882 | −71 | 6287 | 5051 | –20 | 9884 | 2013 | –80 |

| CW*0501(Cw5) | 1230 | 710 | –42 | 7553 | 4013 | –47 | 5975 | 2020 | −66 | 6968 | 6352 | –9 | 8769 | 1513 | –83 |

| CW*0602(Cw6) | 1557 | 627 | –60 | 12049 | 4226 | –65 | 10614 | 2108 | −80 | 9171 | 8176 | –11 | 16706 | 586 | –96 |

| CW*0702(Cw7) | 1973 | 746 | –62 | 11789 | 5474 | –54 | 10541 | 2402 | −77 | 7620 | 3483 | –54 | 15321 | 1619 | –89 |

| CW*0801(Cw8) | 669 | 391 | –42 | 5375 | 3227 | –40 | 4539 | 467 | −90 | 2833 | 1937 | –32 | 4419 | 650 | –85 |

| CW*1203(Cw12) | 985 | 636 | –35 | 7102 | 4807 | –32 | 5608 | 1946 | −65 | 5804 | 2663 | –54 | 8662 | 1624 | –81 |

| CW*1402(Cw14) | 991 | 410 | –59 | 7238 | 3968 | –45 | 6160 | 1073 | −83 | 4272 | 1819 | –57 | 8432 | 976 | –88 |

| CW*1502(Cw15) | 778 | 458 | –41 | 4946 | 3586 | –27 | 3693 | 1198 | −68 | 6167 | 7673 | 24 | 4819 | 255 | –95 |

| CW*1601(Cw16) | 973 | 613 | –37 | 8463 | 4069 | –52 | 6851 | 1557 | −77 | 5376 | 2954 | –45 | 9259 | 1111 | –88 |

| CW*1701(Cw17) | 1487 | 1050 | –29 | 6561 | 6148 | –6 | 5638 | 3253 | −42 | 7856 | 9610 | 22 | 8983 | 2709 | –70 |

| CW*1802(Cw18) | 1549 | 570 | –63 | 8432 | 3579 | –58 | 7155 | 1481 | −79 | 7981 | 7814 | –2 | 10610 | 873 | –92 |

| Antigen . | Sandaglobulin . | Gamunex-C . | GamaSTAN . | Octagam . | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lot NKLG1 . | . | Lot NKLK1 . | |||||||||||||

| Regular, lot 7 . | iBead, lot 6 . | Difference . | Regular, lot 7 . | iBead, lot 6 . | Difference . | Regular, lot 7 . | iBead, lot 6 . | Difference . | Regular, lot 7 . | iBead, lot 6 . | Difference . | Regular, lot 7 . | iBead, lot 6 . | Difference . | |

| (1:4) . | (1:4) . | % . | (1:8) . | (1:8) . | % . | (1:8) . | (1:8) . | % . | (1:8) . | (1:8) . | % . | (1:8) . | (1:8) . | % . | |

| A. | |||||||||||||||

| Album in–NC | 1196 | 667 | –44 | 10753 | 7147 | –34 | 10268 | 7799 | –24 | 3793 | 5034 | 33 | 2340 | 1673 | –29 |

| A*0101(A1) | 0 | 551 | 100 | 368 | 3589 | 875 | 0 | 1355 | 100 | 0 | 809 | 100 | 260 | 262 | 1 |

| A*0201(A2) | 8 | 772 | 9550 | 0 | 4976 | 100 | 0 | 1989 | 100 | 659 | 2215 | 236 | 0 | 1002 | 100 |

| A*0203(A2) | 0 | 354 | 100 | 0 | 2975 | 100 | 233 | 648 | 178 | 24 | 328 | 1258 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| A*0206(A2) | 125 | 799 | 539 | 445 | 4409 | 891 | 913 | 2303 | 152 | 471 | 3061 | 550 | 780 | 1330 | 71 |

| A*0301(A3) | 2 | 199 | 9850 | 0 | 2839 | 100 | 410 | –211 | –151 | 236 | 0 | –100 | 515 | 0 | –100 |

| A*1101(A11) | 187 | 439 | 135 | 2535 | 3763 | 48 | 1942 | 1301 | –33 | 1073 | 1226 | 14 | 1556 | 351 | –77 |

| A*1102(A11) | 115 | 475 | 313 | 824 | 2861 | 247 | 529 | 858 | 62 | 1089 | 1859 | 71 | 829 | 46 | –94 |

| A*2301(A23) | 373 | 667 | 79 | 1775 | 3567 | 101 | 1125 | 1338 | 19 | 1877 | 1178 | –37 | 1417 | 576 | –59 |

| A*2402(A24) | 567 | 725 | 28 | 3171 | 4513 | 42 | 2352 | 2090 | –11 | 2312 | 2218 | –4 | 3071 | 663 | –78 |

| A*2403(A24) | 366 | 593 | 62 | 2701 | 3977 | 47 | 2049 | 1668 | –19 | 2297 | 1462 | –36 | 2868 | 443 | –85 |

| A*2501(A25) | 143 | 581 | 306 | 506 | 2975 | 488 | 488 | 408 | –16 | 1436 | 1905 | 33 | 790 | 58 | –93 |

| A*2601(A26) | 188 | 638 | 239 | 1732 | 4418 | 155 | 1116 | 1560 | 40 | 1004 | 1565 | 56 | 1169 | 402 | –66 |

| A*2901(A29) | 275 | 916 | 233 | 1243 | 4562 | 267 | 634 | 1418 | 124 | 897 | 3265 | 264 | 1046 | 1172 | 12 |

| A*2902(A29) | 200 | 932 | 366 | 1751 | 6014 | 243 | 820 | 2892 | 253 | 991 | 4433 | 348 | 1578 | 2268 | 44 |

| A*3001(A30) | 222 | 540 | 143 | 2107 | 4466 | 112 | 1230 | 1339 | 9 | 924 | 624 | –32 | 928 | 510 | –45 |

| A*3002(A30) | 174 | 526 | 202 | 896 | 3705 | 314 | 562 | 1412 | 151 | 1050 | 929 | –11 | 533 | 369 | –31 |

| A*3101(A31) | 0 | 295 | 100 | 166 | 3411 | 1955 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 121 | 351 | 189 | 366 | 0 | –100 |

| A*3201(A32) | 255 | 769 | 202 | 875 | 3764 | 330 | 424 | 915 | 116 | 856 | 1821 | 113 | 738 | 518 | –30 |

| A*3301(A33) | 185 | 684 | 270 | 1694 | 4462 | 163 | 925 | 1315 | 42 | 1119 | 1877 | 68 | 1494 | 1358 | –9 |

| A*3303 (A33) | 0 | 439 | 100 | 476 | 3329 | 599 | 179 | 517 | 189 | 322 | 725 | 125 | 542 | 152 | –72 |

| A*3401(A34) | 640 | 1150 | 80 | 3543 | 5215 | 47 | 2149 | 3415 | 59 | 3042 | 4323 | 42 | 2879 | 2059 | –28 |

| A*3402(A34) | 0 | 177 | 100 | 0 | 2053 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 684 | 1206 | 76 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| A*3601(A36) | 51 | 636 | 1147 | 916 | 3949 | 331 | 704 | 1551 | 120 | 564 | 1379 | 145 | 778 | 572 | –26 |

| A*4301(A43) | 397 | 949 | 139 | 1961 | 5601 | 186 | 1170 | 2719 | 132 | 1913 | 4182 | 119 | 1898 | 1693 | –11 |

| A*6601(A66) | 93 | 783 | 742 | 648 | 5328 | 722 | 875 | 2331 | 166 | 1408 | 2613 | 86 | 1695 | 1019 | –40 |

| A*6602(A66) | 364 | 768 | 111 | 1101 | 5194 | 372 | 838 | 1863 | 122 | 2362 | 4316 | 83 | 3650 | 684 | –81 |

| A*6801(A68) | 0 | 307 | 100 | 0 | 3148 | 100 | 0 | 662 | 0 | 192 | 634 | 230 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| A*6802(A68) | 455 | 596 | 31 | 1421 | 4662 | 228 | 1332 | 1948 | 46 | 2060 | 2084 | 1 | 1748 | 489 | –72 |

| A*6901(A69) | 470 | 788 | 68 | 2813 | 6243 | 122 | 2777 | 2885 | 4 | 1877 | 2410 | 28 | 1724 | 814 | –53 |

| A*7401(A74) | 0 | 316 | 100 | 666 | 3904 | 486 | 224 | 515 | 130 | 80 | 431 | 437 | 201 | 82 | –59 |

| A*8001(A80) | 401 | 564 | 41 | 3194 | 3969 | 24 | 1679 | 1188 | –29 | 2705 | 2847 | 5 | 2289 | 845 | –63 |

| B. | |||||||||||||||

| Albumin NC | 1196 | 667 | –44 | 10753 | 7147 | –34 | 10268 | 7799 | –24 | 3793 | 5034 | 33 | 2340 | 1673 | –29 |

| B*0702(B7) | 309 | 436 | 41 | 1539 | 2134 | 39 | 837 | 0 | –100 | 2223 | 2010 | –10 | 714 | 0 | –100 |

| B*0801(B8) | 233 | 274 | 18 | 2186 | 1511 | –31 | 1755 | 0 | –100 | 884 | 324 | –63 | 2119 | 114 | –95 |

| B*1301(B13) | 524 | 504 | –4 | 5168 | 3565 | –31 | 3522 | 1031 | –71 | 2244 | 1836 | –18 | 3679 | 52 | –99 |

| B*1302(B13) | 476 | 502 | 5 | 3103 | 1709 | –45 | 2532 | 0 | –100 | 2222 | 1199 | –46 | 1943 | 0 | –100 |

| B*1401(B64) | 621 | 206 | –67 | 3133 | 2100 | –33 | 2276 | 410 | –82 | 1749 | 269 | –85 | 2397 | 102 | –96 |

| B*1402(B65) | 239 | 152 | –36 | 2249 | 929 | –59 | 1441 | 0 | –100 | 670 | 0 | –100 | 1458 | 0 | –100 |

| B*1501(B62) | 0 | 148 | 100 | 0 | 749 | 100 | 15 | 53 | 253 | 106 | 394 | 270 | 100 | 0 | –100 |

| B*1502(B75) | 157 | 245 | 56 | 1525 | 2008 | 32 | 1536 | 91 | –94 | 526 | 709 | 35 | 861 | 0 | –100 |

| B*1503(B72) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2375 | 507 | –79 | 2296 | 0 | –100 | 689 | 0 | –100 | 1057 | 0 | –100 |

| B*1510(B71) | 240 | 271 | 13 | 1434 | 1452 | 1 | 1622 | 347 | –79 | 857 | 492 | –43 | 1293 | 0 | –100 |

| B*1511(B75) | 637 | 552 | –13 | 4058 | 3380 | –17 | 3825 | 1860 | –51 | 2822 | 2380 | –16 | 3640 | 1087 | –70 |

| B*1512(B76) | 382 | 1141 | 199 | 816 | 2811 | 244 | 942 | 1418 | 51 | 2655 | 5973 | 125 | 1129 | 1385 | 23 |

| B*1513(B77) | 550 | 445 | –19 | 4274 | 2353 | –45 | 3211 | 841 | –74 | 1238 | 904 | –27 | 2257 | 256 | –89 |

| B*1516(B63) | 799 | 756 | –5 | 3755 | 2400 | –36 | 3133 | 1212 | –61 | 3536 | 3285 | –7 | 3132 | 880 | –72 |

| B*1801(B18) | 0 | 114 | 100 | 538 | 1142 | 112 | 567 | 0 | –100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 246 | 0 | –100 |

| B*2705(B27) | 141 | 377 | 167 | 388 | 1657 | 327 | 160 | 0 | –100 | 1366 | 1085 | –21 | 154 | 0 | –100 |

| B*2708(B27) | 13 | 302 | 2223 | 0 | 1344 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1067 | 1407 | 32 | 54 | 0 | –100 |

| B*3501(B35) | 243 | 352 | 45 | 1672 | 1614 | –3 | 1478 | 577 | –61 | 680 | 653 | –4 | 964 | 0 | –100 |

| B*3701(B37) | 1099 | 740 | –33 | 6133 | 3639 | –41 | 4788 | 612 | –87 | 3236 | 392 | –88 | 9974 | 0 | –100 |

| B*3801(B38) | 254 | 248 | –2 | 1356 | 1375 | 1 | 1259 | 0 | –100 | 619 | 0 | 100 | 1002 | 0 | –100 |

| B*3901(B39) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 242 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| B*4001(B60) | 237 | 409 | 73 | 1677 | 2474 | 48 | 1240 | 93 | –93 | 1723 | 2286 | 33 | 987 | 4 | –100 |

| B*4002(B61) | 134 | 242 | 81 | 569 | 1679 | 195 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1564 | 1188 | –24 | 271 | 0 | –100 |

| B*4006(B61) | 765 | 359 | –53 | 5394 | 2144 | –60 | 4341 | 421 | –90 | 3470 | 2373 | –32 | 4972 | 167 | –97 |

| B*4101(B41) | 32 | 182 | 469 | 716 | 1486 | 108 | 605 | 0 | –100 | 1067 | 870 | –19 | 393 | 0 | –100 |

| B*4201(B42) | 0 | 86 | 100 | 455 | 1088 | 139 | 13 | 0 | –100 | 598 | 286 | –52 | 364 | 0 | –100 |

| B*4402(B44) | 683 | 461 | –33 | 6465 | 1869 | –71 | 5313 | 786 | –85 | 4301 | 3376 | –22 | 3997 | 702 | –82 |

| B*4403(B44) | 284 | 413 | 45 | 1110 | 2395 | 116 | 1213 | 836 | –31 | 3391 | 2904 | –14 | 1146 | 698 | –39 |

| B*4501(B45) | 272 | 612 | 125 | 1106 | 2110 | 91 | 562 | 399 | –29 | 3667 | 5397 | 47 | 956 | 308 | –68 |

| B*4601(B46) | 537 | 473 | –12 | 3014 | 3537 | 17 | 2450 | 851 | –65 | 1834 | 1460 | –20 | 2438 | 526 | –78 |

| B*4701(B47) | 355 | 655 | 85 | 2554 | 2799 | 10 | 2031 | 1235 | –39 | 1771 | 3211 | 81 | 2200 | 955 | –57 |

| B*4801(B48) | 297 | 341 | 15 | 3280 | 3131 | –5 | 1984 | 757 | –62 | 2252 | 1694 | –25 | 1863 | 104 | –94 |

| B*4901(B49) | 356 | 630 | 77 | 1586 | 1419 | –11 | 1881 | 158 | –92 | 1640 | 446 | –73 | 1340 | 0 | –100 |

| B*5001(B50) | 72 | 198 | 175 | 789 | 968 | 23 | 814 | 0 | –100 | 627 | 176 | –72 | 505 | 0 | –100 |

| B*5101(B51) | 669 | 687 | 3 | 3370 | 2343 | –30 | 2798 | 1101 | –61 | 1662 | 1336 | –20 | 1896 | 339 | –82 |

| B*5102(B51) | 688 | 604 | –12 | 2599 | 1898 | –27 | 2699 | 694 | –74 | 1677 | 476 | –72 | 1671 | 0 | –100 |

| B*5201(B52) | 707 | 869 | 23 | 3207 | 2125 | –34 | 2745 | 1224 | –55 | 1788 | 1341 | –25 | 1962 | 280 | –86 |

| B*5301(B53) | 692 | 536 | –23 | 3265 | 2368 | –27 | 4078 | 678 | –83 | 2040 | 478 | –77 | 2561 | 0 | –100 |

| B*5401(B54) | 299 | 168 | –44 | 2623 | 1463 | –44 | 1455 | 0 | –100 | 1633 | 476 | –71 | 2238 | 0 | –100 |

| B*5501(B55) | 222 | 44 | –80 | 3308 | 1072 | –68 | 1753 | 0 | –100 | 1558 | 686 | –56 | 1874 | 0 | –100 |

| B*5601(B56) | 507 | 183 | –64 | 2689 | 1269 | –53 | 2222 | 0 | –100 | 1995 | 0 | –100 | 1607 | 0 | –100 |

| B*5701(B57) | 419 | 560 | 34 | 1045 | 1987 | 90 | 942 | 286 | –70 | 1101 | 542 | –51 | 957 | 3 | –100 |

| B*5703(B57) | 897 | 382 | –57 | 2710 | 1620 | –40 | 2983 | 0 | –100 | 2148 | 0 | –100 | 2425 | 0 | –100 |

| B*5801(B58) | 726 | 455 | –37 | 4435 | 1829 | –59 | 3479 | 662 | –81 | 2758 | 106 | –96 | 3157 | 0 | –100 |

| B*5901(B59) | 502 | 446 | –11 | 3855 | 2216 | –43 | 3052 | 720 | –76 | 1798 | 1058 | –41 | 2444 | 470 | –81 |

| B*6701(B67) | 225 | 362 | 61 | 64 | 1113 | 1639 | –237 | –569 | 140 | 1108 | 603 | –46 | 841 | 0 | –100 |

| B*7301(B73) | 243 | 572 | 135 | 1817 | 3226 | 78 | 1945 | 1022 | –47 | 1755 | 3145 | 79 | 1740 | 1118 | –36 |

| B*7801(B78) | 446 | 556 | 25 | 2491 | 1568 | –37 | 2410 | 260 | –89 | 1737 | 283 | –84 | 1786 | 0 | –100 |

| B*8101(B81) | 364 | 550 | 51 | 2969 | 3082 | 4 | 1848 | 1096 | –41 | 2541 | 2799 | 10 | 1323 | 372 | –72 |

| B*8201(B82) | 639 | 360 | –44 | 6055 | 2731 | –55 | 4783 | –193 | –104 | 3857 | 4259 | 10 | 5026 | 510 | –90 |

| C. | |||||||||||||||

| Albumin NC | 1196 | 667 | –44 | 10753 | 7147 | –34 | 10268 | 7799 | −24 | 3793 | 5034 | 33 | 2340 | 1673 | –29 |

| CW*0102(Cw1) | 998 | 511 | –49 | 5361 | 5231 | –2 | 4314 | 1058 | −75 | 4538 | 2828 | –38 | 7724 | 1778 | –77 |

| CW*0202(Cw2) | 1275 | 719 | –44 | 7890 | 5379 | –32 | 6814 | 2800 | −59 | 7183 | 8101 | 13 | 9379 | 1840 | –80 |

| CW*0302(Cw10) | 1024 | 522 | –49 | 4952 | 4874 | –2 | 4130 | 1769 | −57 | 4010 | 2378 | –41 | 5608 | 1170 | –79 |

| CW*0303(Cw9) | 703 | 500 | –29 | 4262 | 4286 | 1 | 3017 | 1665 | −45 | 2855 | 2607 | –9 | 3350 | 1220 | –64 |

| CW*0304(Cw10) | 844 | 520 | –38 | 5758 | 4141 | –28 | 4429 | 1816 | −59 | 3713 | 2748 | –26 | 5552 | 1435 | –74 |

| CW*0401(Cw4) | 1569 | 601 | –62 | 7529 | 3726 | –51 | 6484 | 1882 | −71 | 6287 | 5051 | –20 | 9884 | 2013 | –80 |

| CW*0501(Cw5) | 1230 | 710 | –42 | 7553 | 4013 | –47 | 5975 | 2020 | −66 | 6968 | 6352 | –9 | 8769 | 1513 | –83 |

| CW*0602(Cw6) | 1557 | 627 | –60 | 12049 | 4226 | –65 | 10614 | 2108 | −80 | 9171 | 8176 | –11 | 16706 | 586 | –96 |

| CW*0702(Cw7) | 1973 | 746 | –62 | 11789 | 5474 | –54 | 10541 | 2402 | −77 | 7620 | 3483 | –54 | 15321 | 1619 | –89 |

| CW*0801(Cw8) | 669 | 391 | –42 | 5375 | 3227 | –40 | 4539 | 467 | −90 | 2833 | 1937 | –32 | 4419 | 650 | –85 |

| CW*1203(Cw12) | 985 | 636 | –35 | 7102 | 4807 | –32 | 5608 | 1946 | −65 | 5804 | 2663 | –54 | 8662 | 1624 | –81 |

| CW*1402(Cw14) | 991 | 410 | –59 | 7238 | 3968 | –45 | 6160 | 1073 | −83 | 4272 | 1819 | –57 | 8432 | 976 | –88 |

| CW*1502(Cw15) | 778 | 458 | –41 | 4946 | 3586 | –27 | 3693 | 1198 | −68 | 6167 | 7673 | 24 | 4819 | 255 | –95 |

| CW*1601(Cw16) | 973 | 613 | –37 | 8463 | 4069 | –52 | 6851 | 1557 | −77 | 5376 | 2954 | –45 | 9259 | 1111 | –88 |

| CW*1701(Cw17) | 1487 | 1050 | –29 | 6561 | 6148 | –6 | 5638 | 3253 | −42 | 7856 | 9610 | 22 | 8983 | 2709 | –70 |

| CW*1802(Cw18) | 1549 | 570 | –63 | 8432 | 3579 | –58 | 7155 | 1481 | −79 | 7981 | 7814 | –2 | 10610 | 873 | –92 |

An HLA allele with iBead that is higher than that of the regular bead (bold) indicates that the HLA reactivity in question is toward intact HLA. Percentage of increase refers to the same. An MFI of an allele with iBead that is lower than that of the regular bead indicates that the affinity of the antibody is toward the heavy chain of HLA. Percentage of decrease refers to the same.

The dosimetric binding affinity of IgG Abs to nonclassic HLA-Ib (HLA-E, HLA-F, and HLA-G) in different preparations of IVIg is illustrated in Figure 5A-D. The basic profile of reactivity remained the same for all preparations. However, all IVIg preparations except Sandoglobulin reacted equally well with HLA-E and HLA-F. Sandoglobulin showed higher affinity for HLA-G while the dosimetric profile of anti–HLA-E reactivity remained low.

Dosimetric profile of HLA-Ib reactivity of IVIg from the following preparations: GamaSTAN (A), Octagam (B); IVIGlob EX (C); and Sandoglobulin (D).

Dosimetric profile of HLA-Ib reactivity of IVIg from the following preparations: GamaSTAN (A), Octagam (B); IVIGlob EX (C); and Sandoglobulin (D).

Antialbumin antibody reactivity of IVIg

All 4 IVIg preparations reacted with the negative control beads coated with albumin (Table 4), indicating that IVIg contains naturally occurring antialbumin Abs. This finding is consistent with that of earlier reports on the presence of naturally occurring antialbumin antibodies in normal sera.21,22 Among the 4 IVIg preparations, IVIGlob EX (India) showed the highest antialbumin reactivity. The differences could be due to different manufacturing protocols or could reflect the plasma pooled from thousands of different ethnic groups (IVIGlob Ex from India, GamaSTAN from the United States, Octagam from Mexico, and Sandoglobulin from Western Europe). Most often, IVIg reactivity of albumin-coated beads also decreased with iBeads, suggesting that the enzymatic treatment of iBeads used to remove HLA heavy chains also affects the albumin coated on the beads.

Naturally occurring anti-albumin antibodies in IVIg from different sources

| Dilution . | IVIGlob EX (n = 3) . | GamaSTAN (n = 3) . | Octagam (n = 3) . | Sandoglobulin (n = 3) . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean . | SD . | Mean . | SD . | Mean . | SD . | Mean . | SD . | |

| 2 | 21016 | 2731 | 9548 | 1697 | 4916 | 972 | 2964 | 1014 |

| 4 | 12202 | 5963 | 7767 | 362 | 4106 | 1307 | 1650 | 723 |

| 8 | 7829 | 5867 | 4237 | 1416 | 1991 | 600 | 951 | 577 |

| 16 | 3902 | 3651 | 1614 | 516 | 1109 | 464 | 594 | 356 |

| 32 | 1425 | 1516 | 945 | 333 | 356 | 120 | 281 | 182 |

| 64 | 594 | 686 | 315 | 94 | 162 | 42 | 143 | 76 |

| 128 | 255 | 186 | 124 | 15 | 74 | 18 | 71 | 30 |

| 256 | 79 | 48 | 85 | 15 | 56 | 19 | 39 | 8 |

| Dilution . | IVIGlob EX (n = 3) . | GamaSTAN (n = 3) . | Octagam (n = 3) . | Sandoglobulin (n = 3) . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean . | SD . | Mean . | SD . | Mean . | SD . | Mean . | SD . | |

| 2 | 21016 | 2731 | 9548 | 1697 | 4916 | 972 | 2964 | 1014 |

| 4 | 12202 | 5963 | 7767 | 362 | 4106 | 1307 | 1650 | 723 |

| 8 | 7829 | 5867 | 4237 | 1416 | 1991 | 600 | 951 | 577 |

| 16 | 3902 | 3651 | 1614 | 516 | 1109 | 464 | 594 | 356 |

| 32 | 1425 | 1516 | 945 | 333 | 356 | 120 | 281 | 182 |

| 64 | 594 | 686 | 315 | 94 | 162 | 42 | 143 | 76 |

| 128 | 255 | 186 | 124 | 15 | 74 | 18 | 71 | 30 |

| 256 | 79 | 48 | 85 | 15 | 56 | 19 | 39 | 8 |

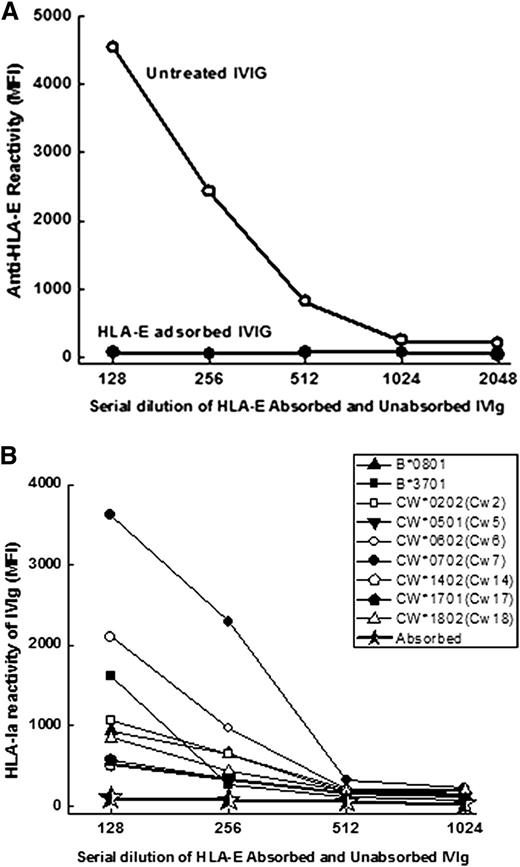

IVIg lost reactivity to both HLA-E and HLA-Ia after HLA-E-Sephadex elution

To ascertain whether the immunoreactivity to HLA-Ia alleles is due to the anti–HLA-E Abs naturally present in IVIg, the anti–HLA-E Abs were adsorbed out with Sephadex gel conjugated with recombinant HLA-E, then tested for HLA-E and HLA-Ia reactivity. As shown in Figure 6A and B, IVIg immunoreactivity to both HLA-E and HLA-Ia is lost after the adsorbing-out process.

Anti–HLA-E Abs and HLA Ia reactivity of anti–HLA-E Abs in IVIg (IVIGlob EX) before (untreated) and after adsorption to HLA-E conjugated Sephadex column. Loss of anti–HLA-E Abs after adsorption (A). Loss of HLA-Ia reactivity after adsorption (*) of anti–HLA-E Abs from IVIg (B).

Anti–HLA-E Abs and HLA Ia reactivity of anti–HLA-E Abs in IVIg (IVIGlob EX) before (untreated) and after adsorption to HLA-E conjugated Sephadex column. Loss of anti–HLA-E Abs after adsorption (A). Loss of HLA-Ia reactivity after adsorption (*) of anti–HLA-E Abs from IVIg (B).

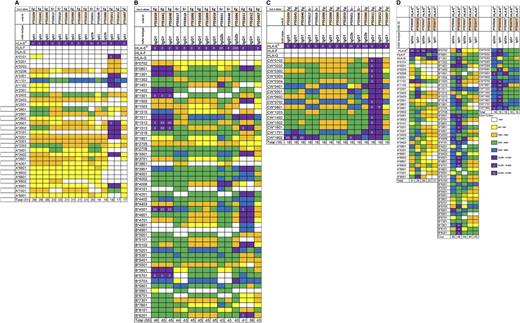

Immunization with HLA-E–generated anti–HLA-E mAbs with anti–HLA-Ia reactivity

In addition to anti–HLA-E Abs, IVIg also contains Abs that react to HLA-F and HLA-G. To find out whether anti–HLA-E antibody can also react with HLA-F and HLA-G and whether such an antibody can still react to HLA-Ia alleles, we generated >100 hybridoma clones secreting mAbs that react to HLA-E. There are 2 kinds of mAb groups or clones that secrete mAbs: (1) mAbs reacting to HLA-E and HLA-Ia but not reactive to HLA-F and HLA-G alleles (Figure 7 A-C) and (2) mAbs reacting to HLA-E, HLA-F, HLA-G, and HLA-Ia alleles (Figure 7D). The results demonstrated that immunization with HLA-E can generate anti–HLA-E mAbs that mimic HLA-Ia reactivity with or without affinity for HLA-F and HLA-G. The anti–HLA-E mAbs that react to HLA-F and HLA-G in addition to HLA-Ia appear to truly mimic IVIg.

Anti–HLA-E mAbs to the recombinant polypeptides of major HLA-E alleles (HLA-ER and HLA-EG). Anti–HLA-E mAbs did not react to HLA-F or HLA-G but did react to HLA class-Ia alleles anti–HLA-E mAbs. HLA-A* allelic reactivity of the anti–HLA-E mAbs (A); HLA-B* allelic reactivity of the anti–HLA-E mAbs (B); HLA-Cw* allelic reactivity of the anti–HLA-E mAbs (C). Anti–HLA-E mAbs reacting to HLA-F and HLA-G and also to all of the HLA class-Ia alleles (HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-Cw), mimicking the HLA-Ia and HLA-Ib reactivity of IVIg (D). These anti–HLA-E mAbs (D) are considered to be IVIg-mimetics because of the parallel HLA reactivity.

Anti–HLA-E mAbs to the recombinant polypeptides of major HLA-E alleles (HLA-ER and HLA-EG). Anti–HLA-E mAbs did not react to HLA-F or HLA-G but did react to HLA class-Ia alleles anti–HLA-E mAbs. HLA-A* allelic reactivity of the anti–HLA-E mAbs (A); HLA-B* allelic reactivity of the anti–HLA-E mAbs (B); HLA-Cw* allelic reactivity of the anti–HLA-E mAbs (C). Anti–HLA-E mAbs reacting to HLA-F and HLA-G and also to all of the HLA class-Ia alleles (HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-Cw), mimicking the HLA-Ia and HLA-Ib reactivity of IVIg (D). These anti–HLA-E mAbs (D) are considered to be IVIg-mimetics because of the parallel HLA reactivity.

These mAbs shared several features observed in IVIg. Essentially, both groups were strikingly similar to IVIg preparations in that they showed stronger reactivity to Cw alleles than to HLA-B and HLA-A alleles. Both groups of mAbs reacted with all 16 Cw alleles tested. Comparing Figure 7A and B with Figure 4, it may be noted that the highest reactivity was observed with Cw*0501, Cw*0602, Cw*0801, Cw*1601, and Cw1802. Both categories of mAbs reacted with several B* alleles; high reactivity was observed with B*8201, B*1512, and B*4501. Similar to IVIg, both sets of mAbs also reacted less with A* alleles. The HLA-Ia reactivity of these mAbs, as well as IVIg, is comparable with the high incidence of HLA-Ia reactivities found in normal sera.13

Discussion

Our principal finding is that all pharmaceutical preparations of IVIg tested contain high titers of antibodies to HLA-E and possess remarkable reactivity to a wide variety of HLA-Ia alleles (HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-Cw). Others have noted the presence of HLA-Ia Abs in IVIg,23-25 but this is the first description of the presence of HLA-E Abs with concomitant profiles of HLA-I reactivity of IVIg. This is a significant finding because it may actually be the antibody to HLA-E that led to broad HLA-1a activity. The sharing of common epitopes between HLA-E and HLA-1a alleles was demonstrated by peptide inhibition of the binding of mouse monoclonal anti–HLA-Abs14,15 and human sera anti–HLA-E Abs13 to HLA-E and HLA-Ia alleles. If, indeed, anti–HLA-E Ab is an active component of IVIg, it follows that anti–HLA-E mAb would be a simpler and more uniform product and might, therefore, replace the IVIg preparations currently in use.

In 2004, the FDA approved the Cedars–Sinai IVIg infusion protocol for desensitizing anti-HLA Abs (panel reactive antibodies [PRA] Abs) so that patients waiting for kidney transplants could accept a graft from any healthy living donor, regardless of blood type (ABO incompatible) or tissue match. The protocol also makes it possible to lower de novo anti-HLA Abs in transplant recipients, based on the reported efficacy of IVIg.26 Various mechanisms have been proposed for lowering anti-HLA Abs by IVIg. Though it was suggested that anti-idiotypic antibodies against anti-HLA Abs in IVIg might be responsible for the reduction of pretransplant or de novo HLA Ab,2-4 Barocci et al27 failed to detect anti-idiotypic Abs (Ab2 directed against Ab1 anti-HLA) in several IVIg preparations. Another possibility is that IVIg binds through the Fc portion of IgG to the inhibitory FcγRIIb that is expressed on a variety of blood cells, including B cells, leading to the reduction of proliferation and apoptosis induction.28 These earlier reports of the efficacy of IVIg in suppressing antibody production and B-cell proliferation have been recently contradicted; newer research shows that IVIg suppresses neither antibody production6-8 nor B-cell proliferation.29 Alternatively, some other suppressive type of feedback mechanism may be involved in lowering HLA antibody production such as that of anti-RhD antibodies.30,31 The prevailing mechanism seems to be that the anti-RhD reacts with RhD+RBC (RhD blood group positive Red Blood cells) and the complex then inhibits further antibody production.32 Antigen-specific IgG administered with an antigen can inhibit antigen-specific antibody production.32,33 All IVIg preparations show HLA class-Ia antibody reactivity. It is also known that IVIg contains soluble HLA class-I antigens.34-36 Possibly, HLA antibodies in IVIg act similar to anti-RhD antibodies. It is likely that use of a more uniform product such as the monoclonal anti–HLA-E IgG described in this study (Figure 7-II) yields more consistent results.

A primary objective of using IVIg in patients waiting for transplantation—and for allograft recipients—is to lower the titers of preexisting and posttransplant anti-HLA Abs.2-5 This investigation documents that IVIg per se contains reactivity to most of the HLA-Ia alleles (Table 2). Hence, it is doubtful that IVIg can lower HLA antibodies, particularly when IVIg by itself contains high HLA-Ia Abs reactivities. Three recent clinical studies document that IVIg preparations were unable to reduce HLA Abs.6-8 In the first,6 IVIg failed to lower the mean percentage of pretransplant HLA Abs observed before IVIg infusion (85% before, 80% after IVIg; P = .1). On the contrary, an increase in anti–HLA-Ia Abs was observed after IVIg in 27% of the patients. In the second study,7 titled “infusion of high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin fails to lower the strength of human leukocyte antigen antibodies in highly sensitized patients,” the authors confirmed that HLA antibody profiles, measured by calculated PRA, showed no significant change in response to IVIg treatment. The third study8 also documented that IVIg—even with rituximab—did not lead to any significant reduction in patients’ anti–HLA-Ia Abs calculated by PRA levels or MFI measured with Luminex single antigen beads. Importantly, none of these studies corroborate previous claims of the reduction of HLA antibodies (calculated panel reactive antibody) in sensitized patients undergoing desensitization with high-dose IVIg. There are 2 explanations for these divergent results: first, IVIG has no real influence on HLA antibodies as claimed in the reports; second, due to the extreme variability in the level of HLA antibodies in the different IVIg preparations, as documented here, some IVIg preparations and lots may not have the ability to lower HLA antibodies in patients. Indeed, until now, no real evidence has been produced as to exactly what the active ingredient in IVIG is that lowers antibodies.

We were surprised that the HLA antibodies in many of the commercial preparations contained HLA antibodies in high titers and that these antibodies were often against intact HLA antigens (HLA-A and -B but not HLA-Cw). We had assumed that most of the antibodies were against heavy chains of HLA antigens, as reported in normal males.37 Concentration of these antibodies during the process of purifying IgG might be expected to produce high levels of reactivity against heavy chains of HLA antigens. The antibodies to intact HLA antigens found in IVIg might have come from alloimmunized plasma (eg, pregnancy plasma) since nonalloimmunized males do not have such antibodies.

The presence of antibodies to intact HLA is of some concern since in high titers they can be expected to produce TRALI.25 Indeed, 5 instances of TRALI following administration of IVIG have been reported,38-42 with 1 death.41 These studies suggest that further use of IVIg should be preceded by titer tests of HLA antibodies because there is a distinct possibility that the active agent in IVIg is actually the HLA antibody itself. Consequently, a balancing of the danger of TRALI must be carefully considered, and the effective action of the HLA antibody must be monitored when using IVIg. It is likely that TRALI will be produced by antibodies to intact HLA antigens. The other possibility is that the monoclonal anti-HLA-E antibody can potentially replace IVIg, because the antibody reacts with denatured or heavy chain of HLA-I antigens. Therefore it may not cause TRALI as is caused by IVIg and at the same time have antibody-lowering effect of IVIg. Of course, the monoclonal antibody will have the added advantage of being a uniform agent with more predictable effect.

The mechanism of IVIg’s action has not been clarified in KD, a pediatric systemic vasculitis of unknown cause. However, administration of IVIg reduces coronary artery abnormalities such as aneurisms from 20% to 25% to 3% to 5% within 10 days of illness onset.43 Recently, Lin et al44 highlighted the role of HLA-E in the pathogenesis of KD. They measured plasma concentrations of soluble HLA-E (sHLA-E) by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in 96 Taiwanese patients with KD and in 93 healthy controls. Levels of sHLA-E in plasma of KD patients were significantly higher than those in plasma of the healthy controls (mean + SD: 209.9 + 85.19 ng/mL vs 63.63 + 13.25 ng/mL; P = .0001). Plasma levels of sHLA-E were also analyzed in relation to genotypes of KD patients. These findings, in light of the present study, suggest that the anti–HLA-E Abs in IVIg may be involved in neutralizing or eliminating sHLA-E. As noted above, it is likely that use of a more uniform product, such as monoclonal anti–HLA-E IgG (IVIg-mimetic), will yield less expensive but better or similar results. Anti–HLA-E mAbs mimicking HLA-Ia and -Ib reactivity of IVIg may have therapeutic potential by neutralizing the immunomodulatory effects of soluble HLA class-I antigens.

Increased cellular expression of HLA-E, induced by proinflammatory cytokines (eg, γ), is correlated with inflammation and malignancy and release of sHLA-E into the circulatory system.45 The sHLA-E occurs without β2m. In the intact HLA-E, the presence of β2m may mask some of the peptide sequences of the heavy chain. When sHLA-E is devoid of β2m, the peptide sequences otherwise masked by β2m in intact HLA-E are exposed to elicit an immune response. It is estimated that 100 mL of cell-free plasma is sufficient to induce HLA-specific allo-Abs in the recipient.46 Antibodies to HLA-E may be produced by β2m-free sHLA-E during pathological events such as inflammation. This could be one reason for the presence of anti–HLA-E Abs in alloimmunized males and healthy females. Possibly, the same explanation can be extended for the presence of anti–HLA-E Abs in IVIg. Indeed, immunogenic sHLA class-I molecules were reported in IVIg.34-36

In addition to anti–HLA-E Abs, IVIg may contain anti–HLA-F and anti–HLA-G Abs (Figure 5A-D). Observations of anti–HLA-E mAbs (Figure 7B) suggest that the HLA-F and HLA-G reactivities in IVIg could be due to Abs against HLA-E. IVIg also shows reactivity to HLA-Ia (HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-Cw; Figure 4A-C). Because the anti–HLA-Ia reactivity is lost concomitantly with loss of anti–HLA-E Abs when IVIg is passed through HLA-E–conjugated Affi-Gel, it is inferred that the anti–HLA-E Abs mimic the HLA-Ia reactivity (Figure 6A,B). Such a possibility may be realized if the Abs in IVIg recognize an epitope common to HLA-E and HLA-Ia—or even to other HLA-Ib alleles. Table 5 provides the profiles of such shared amino acid sequences or epitopes. These shared epitopes were identified,14(Tab1,4) localized on the heavy-chain polypeptide,15 synthesized, and applied in order to inhibit the HLA-E binding of anti–HLA-E mAbs MEM-E/02,14(Fig2,4B,C,E ) 3D12,15 and sera of normal, healthy nonalloimmunized males.14 Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that anti–HLA-E polyclonal Abs in IVIg may be recognizing 1 or more such shared peptides in both HLA class-Ia and -Ib alleles. Recognition of such shared peptides in HLA-Ia alleles implies that anti–HLA-E Abs in IVIg are mimicking HLA-Ia reactivity. This study concludes that the multiple allo-HLA-Ia reactivity of IVIg may not be due to specific allo-Abs produced against individual HLA class-Ia alleles but to reactivity mediated by anti–HLA-E Abs.

Shared epitopes recognized by anti–HLA-E mAbs10,11 and human sera9

| HLA-E peptide sequence or epitope (total number of amino acids) . | HLA allele . | Specificity . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HLA class-Ia . | HLA class-Ib . | |||||

| A . | B . | Cw . | F . | G . | ||

| 90AGSHTLQW97 (8) | 1 | 10 | 48 | 0 | 0 | HLA-Ia reactive |

| 115QFAYDGKDY123 (9) | 1 | 104 | 75 | 0 | 0 | HLA-Ia reactive |

| 116AYDGKDY123 (7) | 491 | 831 | 271 | 21 | 30 | HLA-Ia/Ib reactive |

| 126LNEDLRSWTA135 (10) | 239 | 219 | 261 | 21 | 30 | HLA-Ia/Ib reactive |

| 137DTAAQI142 (6) | 0 | 824 | 248 | 0 | 30 | HLA-Ia/G reactive |

| 137DTAAQIS143 (7) | 0 | 52 | 4 | 0 | 30 | HLA-Ia/G reactive |

| 163TCVEWL168 (6) | 282 | 206 | 200 | 0 | 30 | HLA-Ia/G reactive |

| HLA-E peptide sequence or epitope (total number of amino acids) . | HLA allele . | Specificity . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HLA class-Ia . | HLA class-Ib . | |||||

| A . | B . | Cw . | F . | G . | ||

| 90AGSHTLQW97 (8) | 1 | 10 | 48 | 0 | 0 | HLA-Ia reactive |

| 115QFAYDGKDY123 (9) | 1 | 104 | 75 | 0 | 0 | HLA-Ia reactive |

| 116AYDGKDY123 (7) | 491 | 831 | 271 | 21 | 30 | HLA-Ia/Ib reactive |

| 126LNEDLRSWTA135 (10) | 239 | 219 | 261 | 21 | 30 | HLA-Ia/Ib reactive |

| 137DTAAQI142 (6) | 0 | 824 | 248 | 0 | 30 | HLA-Ia/G reactive |

| 137DTAAQIS143 (7) | 0 | 52 | 4 | 0 | 30 | HLA-Ia/G reactive |

| 163TCVEWL168 (6) | 282 | 206 | 200 | 0 | 30 | HLA-Ia/G reactive |

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr Luis Eduardo Morales-Buenrostro, Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición, Salvador Zubiran, Mexico, for providing IVIg samples; Dr Miyuki Ozawa, One Λ, Inc, for providing IVIg preparation 4; and Dr Feroz Aziz, visiting clinical urologist, and Dr Stanley Jordan, Cedars-Sinai, Los Angeles, for providing lots NKLG1 and NKLK1 of the Gamunex-C.

Authorship

Contribution: M.H.R. formulated the hypothesis, designed the testing of the hypothesis, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper. P.I.T. designed the tests for validation of the hypothesis with iBeads on reactivity to intact vs heavy chains of HLA, coanalyzed the data, wrote a major part of the revised Introduction and first three paragraphs of revised discussion, and provided support by periodic monitoring. T.P., V.J., and S.K. performed the assays, assisted in development of the assays and presentation of the results, and proofread the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Mepur H. Ravindranath, MSc, PhD, Terasaki Foundation Laboratory, 11570 W Olympic Blvd, Los Angeles, CA 90064; e-mail: ravimh@terasakilab.org.