Abstract

The treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia has improved considerably after recognition of the effectiveness of all-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA), anthracycline-based chemotherapy, and arsenic trioxide (ATO). Here we report the use of all 3 agents in combination in an APML4 phase 2 protocol. For induction, ATO was superimposed on an ATRA and idarubicin backbone, with scheduling designed to exploit antileukemic synergy while minimizing cardiotoxicity and the severity of differentiation syndrome. Consolidation comprised 2 cycles of ATRA and ATO without chemotherapy, followed by 2 years of maintenance with ATRA, oral methotrexate, and 6-mercaptopurine. Of 124 evaluable patients, there were 4 (3.2%) early deaths, 118 (95%) hematologic complete remissions, and all 112 patients who commenced consolidation attained molecular complete remission. The 2-year rate for freedom from relapse is 97.5%, failure-free survival 88.1%, and overall survival 93.2%. These outcomes were not influenced by FLT3 mutation status, whereas failure-free survival was correlated with Sanz risk stratification (P[trend] = .03). Compared with our previously reported ATRA/idarubicin-based protocol (APML3), APML4 patients had statistically significantly improved freedom from relapse (P = .006) and failure-free survival (P = .01). In conclusion, the use of ATO in both induction and consolidation achieved excellent outcomes despite a substantial reduction in anthracycline exposure. This trial was registered at the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (www.anzctr.org.au) as ACTRN12605000070639.

Medscape EDUCATION Continuing Medical Education online

This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the Essential Areas and policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education through the joint sponsorship of Medscape, LLC and the American Society of Hematology. Medscape, LLC is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

Medscape, LLC designates this Journal-based CME activity for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

All other clinicians completing this activity will be issued a certificate of participation. To participate in this journal CME activity: (1) review the learning objectives and author disclosures; (2) study the education content; (3) take the post-test with a 70% minimum passing score and complete the evaluation at http://www.medscape.org/journal/blood; and (4) view/print certificate. For CME questions, see page 1752.

Disclosures

Harry J. Iland, Frank Firkin, and John F. Seymour served as consultants for Phebra. John Reynolds was a statistician for ALLG; he has since joined Novartis. The remaining authors, the Associate Editor Martin S. Tallman, and CME questions author Laurie Barclay, freelance writer and reviewer, Medscape, LLC, declare no competing financial interests.

Learning objectives

Upon completion of this activity, participants will be able to:

Describe the acute promyelocytic leukemia (APML4) phase-2 protocol.

Describe efficacy outcomes with the APML4 phase-2 protocol, based on a study of 124 patients.

Describe safety outcomes with the APML4 phase-2 protocol, based on a study of 124 patients.

Release date: August 23, 2012; Expiration date: August 23, 2013

Introduction

Acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) is a discrete subtype of acute myeloid leukemia characterized by a t(15;17) translocation, rearrangement of the PML and RARA genes, and formation of an abnormal chimeric retinoic acid receptor transcription factor (PML-RARA).1 The latter disrupts normal myeloid differentiation programs, but simultaneously imparts a unique sensitivity on APL cells to pharmacologic doses of all-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA).2 The combination of ATRA and anthracycline-based chemotherapy for induction and consolidation has achieved dramatic improvements in outcome for patients with APL, with long-term disease-free survival (DFS) now exceeding 80%.3,4

Arsenic trioxide (ATO) is also a highly effective antileukemic agent in APL. ATRA and ATO degrade PML-RARA synergistically, resulting in the eradication of APL-initiating cells,5 and ATO is currently the agent of choice for treating relapse after initial ATRA-anthracycline therapy.6–8 Several studies have now reported its use, either as a single agent9,10 or in combination with ATRA,11,12 as initial induction therapy for APL, with relapse rates approximating those that have been achieved with ATRA and multiple cycles of chemotherapy. The benefit of adding ATO in consolidation has also been demonstrated in a randomized North American Leukemia Intergroup trial.13

In an attempt to build on the proven benefits of ATRA and idarubicin,14–16 and to exploit the potent antileukemic efficacy of ATO, the Australasian Leukaemia and Lymphoma Group (ALLG) initiated a single-arm, phase 2 study using triple induction with ATRA, idarubicin, and ATO for patients with newly diagnosed APL. Consolidation consisted of 2 additional cycles of ATRA and ATO without chemotherapy, and was followed by maintenance with ATRA, oral methotrexate (MTX), and 6-mercaptopurine (6MP). We report herein the results of a protocol-specified interim analysis showing outstanding antileukemic efficacy combined with acceptable tolerability when delivered in a multi-institutional setting. The ALLG's previous APML3 study,16 which used ATRA and idarubicin in both induction and consolidation without ATO, provides an appropriate historic control with which to illustrate the benefits of incorporating ATO in the initial therapy for APL.

Methods

Patients

This trial was approved by human research ethics committees in all participating ALLG and Australian & New Zealand Children's Haematology/Oncology Group centers, and was registered at the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (www.anzctr.org.au) as ACTRN12605000070639. Patients were accrued between November 2004 and September 2009. Eligibility criteria included: morphologic diagnosis of de novo APL according to French-American-British criteria; demonstration of PML-RARA fusion transcripts by RT-PCR or cytogenetic demonstration of t(15;17); Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status 0-3; age > 1 year with no upper limit; normal left ventricular ejection fraction and Q-Tc interval < 500 milliseconds; a negative pregnancy test in females of child-bearing potential; no prior treatment for APL; no history of grand mal seizures or cancer (other than basal cell skin cancer or carcinoma of the cervix in situ); absence of serious cardiac, pulmonary, hepatic, or renal disease; and written informed consent. Patients with genetic variants of APL (X-RARA where X was not PML) were ineligible. Patient registration, data collection and validation, and statistical analyses were performed at the Centre for Biostatistics and Clinical Trials (Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, East Melbourne, Australia).

APML4 protocol

Induction (Table 1) comprised ATRA 45 mg/m2/d plus age-adjusted IV idarubicin, given on days 2, 4, 6, and 8, followed on day 9 by IV ATO 0.15 mg/kg/d (Phebra). Blood product support was administered to achieve protocol-specified platelet and coagulation targets. Because both ATRA and ATO can induce APL differentiation syndrome (DS), prednisone 1 mg/kg/d was administered prophylactically to all patients for at least 10 days regardless of WBC count at presentation. The use of heparin, antifibrinolytics, and G-CSF was discouraged. Decisions regarding when to use antibiotics, antivirals, and antifungals and the choice of specific agents were left to individual investigators. Twice weekly electrocardiographic surveillance was combined with 3 times per week electrolyte assessment to minimize the risk of arrhythmias due to arsenic-associated Q-Tc prolongation. For grade 3-4 nonhematologic toxicity, treatment with ATRA and/or ATO was either suspended temporarily or reduced to doses still known to be active (25 mg/m2/d and 0.08 mg/kg/d, respectively). When ATRA or ATO was omitted for 3 or more days, the treatment duration was extended beyond day 36 to compensate for the omitted doses.

Induction was followed by 2 consolidation cycles with ATRA and ATO (Table 1); both agents were given continuously in cycle 1 and intermittently in cycle 2 (to facilitate outpatient administration of ATO and to minimize the risk of developing ATRA resistance). Maintenance therapy continued for 2 years and consisted of eight 3-monthly cycles. ATRA was administered alone for the first 2 weeks of each cycle; oral MTX and 6MP were taken for the remainder of each cycle, targeting a neutrophil count of 1-2 × 109/L with dose adjustments for excessive myelosuppression or hepatotoxicity. BM morphology, cytogenetics, and quantitative RT-PCR for PML-RARA were performed after induction and each consolidation cycle. Subsequent BM assessments occurred every 3 months for 36 months (ie, until 12 months after completion of maintenance).

Components of the APML4 protocol

| Induction | ||

| ATRA | 45 mg/m2/d PO | Days 1-36 in divided doses |

| Idarubicin | 12 mg/m2/d IV (ages 1-60) | Days 2, 4, 6, and 8 |

| 9 mg/m2/d IV (ages 61-70) | ||

| 6 mg/m2/d IV (ages > 70) | ||

| ATO | 0.15 mg/kg/d IV | Days 9-36 as a 2-hour IV infusion Supplemental potassium and magnesium as required to maintain serum levels in the upper half of the respective normal ranges |

| Prednisone | 1 mg/kg/d PO | Days 1-10 or until WBC count falls below 1 × 109/L or until resolution of differentiation syndrome (whichever occurs last) |

| Hemostatic support | Products administered once or twice daily as required to achieve specified targets | Platelets > 30 × 109/L Normal prothrombin time Normal activated partial thromboplastin time Fibrinogen > 1.5 g/L |

| Consolidation cycle 1 (3-4 wks after the end of induction) | ||

| ATRA | 45 mg/m2/d PO | Days 1-28 |

| ATO | 0.15 mg/kg/d IV | Days 1-28 |

| Consolidation cycle 2 (3-4 wks after the end of consolidation cycle 1) | ||

| ATRA | 45 mg/m2/d PO | Days 1-7, 15-21, 29-35 |

| ATO | 0.15 mg/kg/d IV | Days 1-5, 8-12, 15-19, 22-26, 29-33 |

| Maintenance: 8 cycles (3-4 wks after the end of consolidation cycle 2) | ||

| ATRA | 45 mg/m2/d PO | Days 1-14 |

| MTX | 5-15 mg/m2/wk PO | Days 15-90 |

| 6MP | 50-90 mg/m2/d PO | Days 15-90 |

| Induction | ||

| ATRA | 45 mg/m2/d PO | Days 1-36 in divided doses |

| Idarubicin | 12 mg/m2/d IV (ages 1-60) | Days 2, 4, 6, and 8 |

| 9 mg/m2/d IV (ages 61-70) | ||

| 6 mg/m2/d IV (ages > 70) | ||

| ATO | 0.15 mg/kg/d IV | Days 9-36 as a 2-hour IV infusion Supplemental potassium and magnesium as required to maintain serum levels in the upper half of the respective normal ranges |

| Prednisone | 1 mg/kg/d PO | Days 1-10 or until WBC count falls below 1 × 109/L or until resolution of differentiation syndrome (whichever occurs last) |

| Hemostatic support | Products administered once or twice daily as required to achieve specified targets | Platelets > 30 × 109/L Normal prothrombin time Normal activated partial thromboplastin time Fibrinogen > 1.5 g/L |

| Consolidation cycle 1 (3-4 wks after the end of induction) | ||

| ATRA | 45 mg/m2/d PO | Days 1-28 |

| ATO | 0.15 mg/kg/d IV | Days 1-28 |

| Consolidation cycle 2 (3-4 wks after the end of consolidation cycle 1) | ||

| ATRA | 45 mg/m2/d PO | Days 1-7, 15-21, 29-35 |

| ATO | 0.15 mg/kg/d IV | Days 1-5, 8-12, 15-19, 22-26, 29-33 |

| Maintenance: 8 cycles (3-4 wks after the end of consolidation cycle 2) | ||

| ATRA | 45 mg/m2/d PO | Days 1-14 |

| MTX | 5-15 mg/m2/wk PO | Days 15-90 |

| 6MP | 50-90 mg/m2/d PO | Days 15-90 |

PO indicates oral administration.

Molecular monitoring

Either peripheral blood or BM was acceptable for demonstration of PML-RARA transcripts at diagnosis, but only BM was acceptable for molecular monitoring after treatment commenced. Of 910 informative samples collected before the study closeout date, 906 (99.6%) were analyzed at a central laboratory (Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Camperdown, Australia). RNA was extracted from mononuclear cells isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque density centrifugation16 or, if necessary, from BM collected simultaneously into RNAlater (Invitrogen). The majority of samples (84%) were assayed by quantitative RT-PCR for PML-RARA fusion transcripts using FusionQuant kits (Ipsogen). The remainder were assayed with a seminested qualitative RT-PCR protocol16 with a sensitivity of at least 10−4 (especially those with more proximal bcr2 breakpoints not amenable to FusionQuant analysis). Identification of mutant FLT3 transcripts, both internal tandem duplications (ITDs) and codon 835/836 mutations, was performed as described previously.16

Definitions and study end points

Hematologic complete remission (hCR) was assessed according to criteria described by the International Working Group.17 Molecular complete remission (mCR) required the absence of detectable PML-RARA transcripts. Relapse was defined as either: (1) the reappearance of abnormal blast cells and/or promyelocytes or the development of extramedullary disease (hematologic relapse) or (2) reversion to PML-RARA positivity confirmed on serial samples after previously documented negativity (molecular relapse), whichever occurred first. The primary end point of the study, freedom from relapse (FFR), was calculated as the time from documented hCR to hematologic or molecular relapse. Secondary end points were measured as follows: overall survival (OS), time from commencement of ATRA therapy to death from any cause; DFS, time from documented hCR to the earliest of relapse or death; and failure-free survival (FFS), time from commencement of ATRA therapy to the earliest of treatment failure, relapse, or death, where treatment failure included failure to achieve mCR by the end of consolidation or withdrawal from protocol therapy because of patient refusal to continue or excessive toxicity. Early death was defined as death during induction (ie, within 36 days from the commencement of ATRA therapy). Adverse events (AEs) were reported using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events Version 3.0 (National Cancer Institute).

Statistical methods

This interim analysis was planned to take place approximately 1 year after accrual had ceased. At the time of analysis, a study closeout (censor) date was set as the earliest of the dates of last contact of patients who were still alive and being followed up. Therefore, with the exception of patients who had been lost to follow-up, the status of all patients in the trial for the time-to-event end points was known at this date. FFR, OS, DFS, and FFS curves were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier product limit method; 2-year survival estimates and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were also calculated. The associations of FLT3 status (wild-type versus ITD and/or codon 835/836 mutations) and Sanz risk stratification18 with time-to-event outcomes were assessed using Cox proportional hazards regression models. The relationship between WBC count at baseline and early death was investigated using binary logistic regression. AEs were summarized descriptively using the number of events and percentages for induction and consolidation separately; McNemar's test was used to compare the incidence of specific grade 3-4 AEs between induction and the first consolidation cycle and also between the first and second consolidation cycles. All statistical analyses were performed in R Version 2.10 software (http://www.R-project.org).

APML3 historic control data

To better assess the impact of adding ATO in induction and consolidation and eliminating chemotherapy from consolidation, data from the ALLG's previous APML3 trial16 were used as a historic control. APML3 involved ATRA and idarubicin induction and consolidation used a second cycle of idarubicin followed by three 14-day blocks of ATRA. APML3 was subsequently amended during the study to incorporate 2 years of maintenance with ATRA, oral MTX, and 6MP. A total of 101 eligible patients were registered in the APML3 trial, but the comparator group used here has been restricted to the 70 patients registered after the maintenance amendment was activated to eliminate differing postconsolidation therapy as a confounding variable. Their median potential follow-up time determined by the reverse Kaplan-Meier method was 48 months (range, 30-68). The time interval between the first patient registered in the APML3 comparator cohort and the first patient registered in the APML4 cohort was 63 months. Comparisons between these cohorts were performed for early death using the Fisher exact test and for time-to-event outcomes using the log-rank test and Cox proportional hazards regression.

Results

Induction

A total of 129 patients from 27 Australian centers were registered. Five patients were excluded from the analysis; 3 patients were negative for both t(15;17) and PML-RARA and 1 of these was subsequently found to have a genetic variant APL (PRKAR1A-RARA)19 ; 1 patient withdrew consent before commencing therapy; and 1 patient with an eligibility infringement (prior malignancy) also withdrew consent. The characteristics of the 124 evaluable patients are summarized in Table 2. With a study closeout date of 16 November 2009, the median potential follow-up time was 24 months (range 2-61).

Pretreatment characteristics of evaluable patients

| Characteristic . | APML4 . | APML3 . | P (APML4 vs APML3) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) . | Median (range) . | n (%) . | Median (range) . | ||

| No. of patients | 124 (100) | 70 (100) | |||

| Age, y | 44 (3-78) | 39 (19-73) | .06 | ||

| Age subgroup, y | |||||

| ≤ 60 | 108 (87) | 63 (90) | |||

| 61-70 | 9 (7) | 6 (9) | .43 | ||

| > 70 | 7 (6) | 1 (1) | |||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 62 (50) | 37 (53) | .77 | ||

| Female | 62 (50) | 33 (47) | |||

| ECOG status | |||||

| 0 | 64 (52) | 37 (53) | |||

| 1 | 43 (35) | 23 (33) | .57 | ||

| 2 | 11 (9) | 9 (13) | |||

| 3 | 6 (5) | 1 (1) | |||

| FAB classification* | |||||

| M3 | 99 (80) | 57 (81) | .85 | ||

| M3v | 25 (20) | 13 (19) | |||

| PML breakpoint† | |||||

| bcr1 | 66 (53) | 38 (57) | |||

| bcr2 | 8 (6) | 6 (9) | .64 | ||

| bcr3 | 50 (40) | 23 (34) | |||

| WBC count, × 109/L | 2.4 (0.1-85.8) | 2.4 (0.4-109.0) | .99 | ||

| Platelet count, × 109/L‡ | 22 (1-173) | 22 (4-180) | .61 | ||

| Sanz risk category‡ | |||||

| Low | 32 (26) | 20 (29) | |||

| Intermediate | 67 (54) | 35 (50) | .85 | ||

| High | 24 (20) | 15 (21) | |||

| FLT3 status§ | |||||

| Wild-type | 66 (56) | 37 (59) | .75 | ||

| Mutation | 52 (44) | 26 (41) | |||

| Characteristic . | APML4 . | APML3 . | P (APML4 vs APML3) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) . | Median (range) . | n (%) . | Median (range) . | ||

| No. of patients | 124 (100) | 70 (100) | |||

| Age, y | 44 (3-78) | 39 (19-73) | .06 | ||

| Age subgroup, y | |||||

| ≤ 60 | 108 (87) | 63 (90) | |||

| 61-70 | 9 (7) | 6 (9) | .43 | ||

| > 70 | 7 (6) | 1 (1) | |||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 62 (50) | 37 (53) | .77 | ||

| Female | 62 (50) | 33 (47) | |||

| ECOG status | |||||

| 0 | 64 (52) | 37 (53) | |||

| 1 | 43 (35) | 23 (33) | .57 | ||

| 2 | 11 (9) | 9 (13) | |||

| 3 | 6 (5) | 1 (1) | |||

| FAB classification* | |||||

| M3 | 99 (80) | 57 (81) | .85 | ||

| M3v | 25 (20) | 13 (19) | |||

| PML breakpoint† | |||||

| bcr1 | 66 (53) | 38 (57) | |||

| bcr2 | 8 (6) | 6 (9) | .64 | ||

| bcr3 | 50 (40) | 23 (34) | |||

| WBC count, × 109/L | 2.4 (0.1-85.8) | 2.4 (0.4-109.0) | .99 | ||

| Platelet count, × 109/L‡ | 22 (1-173) | 22 (4-180) | .61 | ||

| Sanz risk category‡ | |||||

| Low | 32 (26) | 20 (29) | |||

| Intermediate | 67 (54) | 35 (50) | .85 | ||

| High | 24 (20) | 15 (21) | |||

| FLT3 status§ | |||||

| Wild-type | 66 (56) | 37 (59) | .75 | ||

| Mutation | 52 (44) | 26 (41) | |||

French-American-British.

PML breakpoint was not available in 3 APML3 patients, so n = 67.

Pretransfusion platelet count was not available in 1 APML4 patient, so n = 123.

FLT3 status was available for 118 APML4 patients (95%) and 63 APML3 patients (90%); FLT3 mutations included ITDs and/or codon 835/836 mutations.

Four of 124 patients died during induction (early death rate, 3.2%). The causes of death were myocardial ischemia and cardiac arrest (day 1), intracerebral hemorrhage (days 3 and 7), and cerebral edema (day 30). Early deaths were associated with age > 70 years (P = .02), but not with WBC count > 10 × 109/L at diagnosis (P = .17). Two patients withdrew from study during induction without subsequent evaluation of remission status; 1 withdrew on day 29 because he no longer wanted to attend for daily ATO infusions and the other withdrew on day 16 because of grade 4 DS that had commenced before day 9. The latter patient did not receive any ATO before withdrawal, but was treated subsequently with ATO off-protocol. The remaining 118 patients (95%) had hCR documented a median of 53 days (range 34-83) from the start of ATRA therapy. Table 3 lists grade 3-4 nonhematologic AEs observed during induction. Grade 3-4 DS (Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events Version 3.0 retinoic acid syndrome) was reported in 14%, but there were no deaths attributable to DS. Q-Tc prolongation to > 500 ms occurred during ATO therapy in 14% of patients, but there were no instances of torsades de pointes or other severe arrhythmias. One patient developed marked T-wave inversion after the first dose of ATO. Despite cessation of ATO, T-wave inversion persisted and the patient was withdrawn from the study. Whether the preceding 4 doses of idarubicin (total dose, 35 mg/m2) or the single dose of ATO (0.15 mg/kg) was responsible is unclear. Biochemical hepatotoxicity was common, but responded to protocol-specified ATO dose reduction and resolved after ATO withdrawal. Other potential contributors to the observed hepatotoxicity include ATRA, idarubicin, allopurinol, and antifungal prophylaxis. Table 4 lists the spectrum of infections that were reported and the organisms that were identified. Six patients withdrew consent before commencing consolidation because of unacceptable toxicity during induction (2 with severe rash, 2 with infection, 1 with persistent deep T-wave inversion, and 1 with peripheral neuropathy); all 6 patients were in hCR after induction and 4 were also in mCR.

Number of patients experiencing grade 3-4 nonhematologic AEs during induction and consolidation

| . | Induction . | Con 1* . | Con 2† . | P (Induction vs Con 1) . | P (Con 1 vs Con 2) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients for whom AE data are available | 120 (97%) | 112 (100%) | 110 (98%) | ||

| Cardiac‡ | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Prolonged Q-Tc interval | 17 (14%) | 10 (9%) | 4 (4%) | .17 | .11 |

| Hepatic§ | 53 (44%) | 13 (12%) | 2 (2%) | < .0001 | .01 |

| Gastrointestinal¶ | 33 (28%) | 3 (3%) | 1 (1%) | < .0001 | .62 |

| Infection# | 91 (76%) | 21 (19%) | 3 (3%) | < .0001 | .0005 |

| Differentiation syndrome | 17 (14%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | .0005 | |

| Neurological** | 7 (6%) | 2 (2%) | 0 (0%) | .29 | .48 |

| Headache | 4 (3%) | 2 (2%) | 0 (0%) | .68 | .48 |

| Dermatological | 5 (4%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | .48 | |

| Respiratory†† | 2 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Metabolic‡‡ | 19 (16%) | 4 (4%) | 4 (4%) | .002 | 1.0 |

| Second malignancy | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%)§§ | 0 (0%) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| . | Induction . | Con 1* . | Con 2† . | P (Induction vs Con 1) . | P (Con 1 vs Con 2) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients for whom AE data are available | 120 (97%) | 112 (100%) | 110 (98%) | ||

| Cardiac‡ | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Prolonged Q-Tc interval | 17 (14%) | 10 (9%) | 4 (4%) | .17 | .11 |

| Hepatic§ | 53 (44%) | 13 (12%) | 2 (2%) | < .0001 | .01 |

| Gastrointestinal¶ | 33 (28%) | 3 (3%) | 1 (1%) | < .0001 | .62 |

| Infection# | 91 (76%) | 21 (19%) | 3 (3%) | < .0001 | .0005 |

| Differentiation syndrome | 17 (14%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | .0005 | |

| Neurological** | 7 (6%) | 2 (2%) | 0 (0%) | .29 | .48 |

| Headache | 4 (3%) | 2 (2%) | 0 (0%) | .68 | .48 |

| Dermatological | 5 (4%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | .48 | |

| Respiratory†† | 2 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Metabolic‡‡ | 19 (16%) | 4 (4%) | 4 (4%) | .002 | 1.0 |

| Second malignancy | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%)§§ | 0 (0%) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

Consolidation cycle 1.

Consolidation cycle 2.

Conduction abnormalities other than Q-Tc prolongation or left ventricular systolic dysfunction.

Clinical liver failure or elevation of bilirubin, ALT, AST, or GGT.

Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, mucositis, or enterocolitis.

Documented infection or febrile neutropenia.

Dizziness, mood alteration, musculoskeletal pain, or seizure.

Dyspnea or hypoxia not attributed to differentiation syndrome.

Hyperglycemia, hypertriglyceridemia, hypoalbuminemia, hypokalemia, hypophosphatemia, or renal failure.

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of skin. Because the latency of skin cancer related to arsenic exposure is usually measured in years or decades (Levine T, Marcus W, Chen C. US Environmental Protection Agency Risk Assessment Forum: Special Report on Ingested Inorganic Arsenic. Available from: http://www.epa.gov/raf/publications/pdfs/EPA_625_3-87_013.PDF. Accessed April 2, 2012), it is unlikely that this SCC was a consequence of the therapeutic ATO used in this protocol.

Spectrum and number of infections observed during induction and consolidation

| . | Induction . | Consolidation cycle 1 . | Consolidation cycle 2 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bloodstream and/or catheter-related* | 42 | 12 | 3 |

| Respiratory tract† | 15 | 0 | 0 |

| Urinary tract‡ | 4 | 2 | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal§ | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Skin/wound¶ | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Viral# | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| Fungal** | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Miscellaneous | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| . | Induction . | Consolidation cycle 1 . | Consolidation cycle 2 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bloodstream and/or catheter-related* | 42 | 12 | 3 |

| Respiratory tract† | 15 | 0 | 0 |

| Urinary tract‡ | 4 | 2 | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal§ | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Skin/wound¶ | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Viral# | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| Fungal** | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Miscellaneous | 0 | 2 | 0 |

Includes S epidermidis and coagulase-negative Staphylococcus, S aureus, Enterococcus spp, K pneumoniae, K oxytoca, P aeruginosa, S maltophilia, Acinetobacter spp, group B Streptococcus, A baumannii, P putida, A xylosoxidans, S liquefaciens, E cloacae, B cepacia, E faecalis, A lwoffii, M catarrhalis, S salivarus, Clostridium spp, and S cohnii.

Includes E coli, coagulase-negative Staphylococcus, L bozemanii, S maltophilia, and H influenzae.

Includes E coli, E cloacae, and K pneumoniae.

Includes Clostridium spp, E faecium, and E faecalis.

Includes Serratia spp and S aureus.

Includes herpes simplex and herpes zoster.

Includes Aspergillus spp.

Consolidation

Of 118 patients in hCR, 112 (95% of hCR patients and 90% of the total study population) commenced consolidation at a median of 6.5 days (range, 0-28) after documentation of hCR and all 112 (100%) were in mCR by the end of consolidation cycle 2. There were no instances of DS and no deaths were attributed to either of the 2 cycles of consolidation. Grade 3-4 nonhematologic AEs experienced in each consolidation cycle are shown in Table 3 and the spectrum of infections are listed in Table 4. In general, consolidation was associated with considerably less toxicity than induction, and this was especially evident for hepatic, gastrointestinal, infective, and metabolic AEs. Compared with the first cycle of consolidation, biochemical hepatotoxicity and infections were also statistically significantly less frequent in the second cycle when ATO and ATRA were given on an intermittent schedule (weekdays only for ATO and alternate weeks for ATRA). Myelotoxicity associated with ATO was also schedule dependent, because any grade 3-4 cytopenia occurred in 52% of patients during the first cycle of consolidation compared with 24% during the second cycle (P < .0001). This myelotoxicity was predominantly manifest as neutropenia (51% in cycle 1 and 23% in cycle 2). Q-Tc prolongation was less frequent during consolidation than during induction, but the differences were not statistically significant. One episode of ventricular tachycardia occurred in a single patient during the first cycle of consolidation, but this was transient and was not associated with serious sequelae. Toxicities experienced by the 4 pediatric and adolescent patients (ages 3, 15, 16, and 17 years) were comparable with those seen in adult patients.

Outcomes

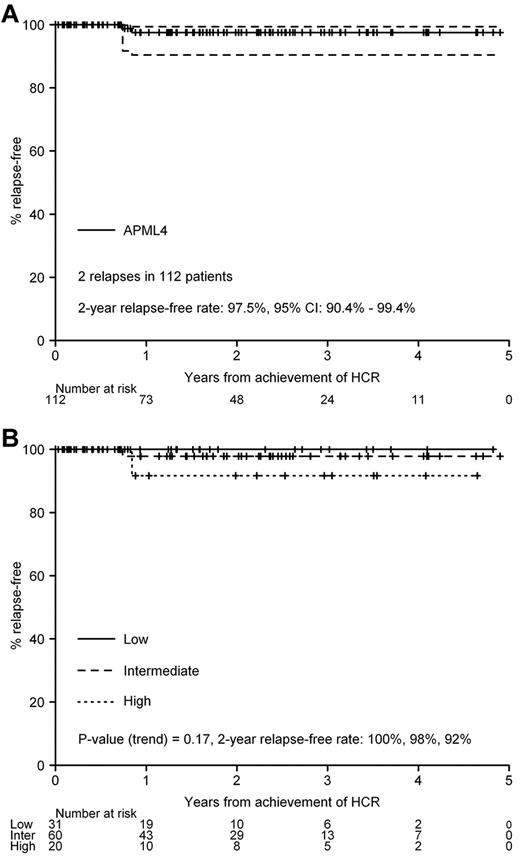

At the closeout date, 2 patients were known to have relapsed after completion of consolidation. One patient (intermediate risk) had a molecular BM relapse 166 days after consolidation cycle 2, followed soon after by overt CNS relapse, and died of progressive disease. The other patient (high risk) had an isolated molecular relapse 189 days after consolidation cycle 2 and died of infective complications related to salvage chemotherapy with intermediate-dose cytarabine and etoposide. The 2-year FFR rate is 97.5% (95% CI: 90.4%-99.4%, Figure 1A), and was unaffected by Sanz risk stratification (P[trend] = .17, Figure 1B). Because there have been no protocol-associated deaths in remission, the estimates for DFS and FFR at 2 years are identical.

FFR. (A) All patients who commenced consolidation (n = 112). (B) Stratification by Sanz risk category.

FFR. (A) All patients who commenced consolidation (n = 112). (B) Stratification by Sanz risk category.

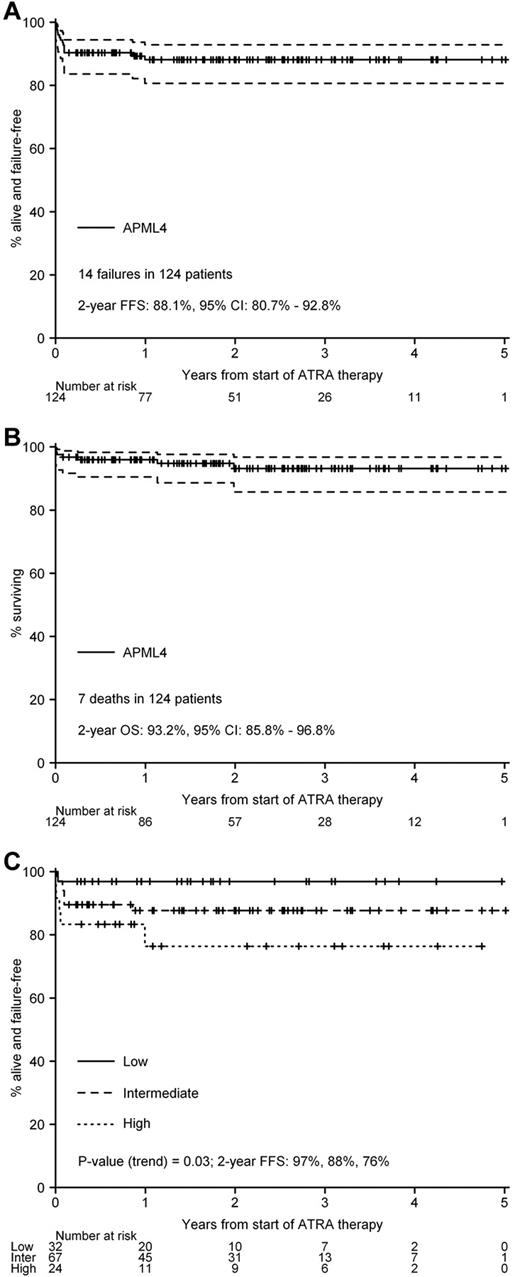

The actuarial 2-year rate for FFS is 88.1% (95% CI, 80.7%-92.8%, Figure 2A), and for OS is 93.2% (95% CI, 85.8%-96.8%, Figure 2B). Sanz risk stratification did not affect OS (P[trend] = .16), but was statistically significantly correlated with FFS (P[trend] = .03, Figure 2C). However, the relevance of this association is tempered by the fact that FFS, as defined in this study, included withdrawal because of patient refusal or excessive toxicity in addition to relapse, death, or failure to achieve mCR. Accordingly, FFS is a less precise end point than FFR, DFS, and OS in identifying patient subgroups with a poorer prognosis. When considered as a continuous covariate, age was not statistically significantly correlated with FFR/DFS (P = .92), OS (P = .10), or FFS (P = .07).

Kaplan-Meier survival curves. (A) FFS. (B) OS. (C) FFS stratified by Sanz risk category.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves. (A) FFS. (B) OS. (C) FFS stratified by Sanz risk category.

Dose delivery

The majority of patients received total doses of idarubicin, ATRA, and ATO above the minimum specified for each cycle of the protocol (Table 5) and most received at least 80% of the maximum specified doses. These data demonstrate the feasibility of combining all 3 drugs and delivering APML4 in a multi-institutional setting.

Summary of idarubicin, ATRA, and ATO doses delivered according to protocol specifications and treatment cycle

| . | No. of patients with data available . | Protocol-specified maximum/minimum* total dose . | Median total dose delivered (range)† . | No. that received at least 80% of the maximum total dose (%) . | No. that received at least 100% of the minimum* total dose (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Induction (n = 121)‡ | |||||

| Idarubicin, mg/m2 | 121 | 24-48§/NA¶ | 47.5 (22.2-52.4) | 118 (97) | NA |

| ATRA, mg/m2 | 118 | 1620/850 | 1584.2 (136.1-1988.1) | 106 (90) | 112 (95) |

| ATO, mg/kg | 117 | 4.2/2.08 | 4.03 (0-4.94) | 84 (72) | 109 (93) |

| Consolidation cycle 1 (n = 112) | |||||

| ATRA, mg/m2 | 110 | 1260/650 | 1269.8 (515.9-2655.0) | 108 (98) | 108 (98) |

| ATO, mg/kg | 109 | 4.2/2.08 | 4.2 (1.97-4.72) | 100 (92) | 108 (99) |

| Consolidation cycle 2 (n = 112) | |||||

| ATRA, mg/m2 | 109 | 945/475 | 948.4 (522.6-1260.0) | 106 (97) | 109 (100) |

| ATO, mg/kg | 111 | 3.75/1.84 | 3.75 (1.66-4.48) | 100 (90) | 110 (99) |

| . | No. of patients with data available . | Protocol-specified maximum/minimum* total dose . | Median total dose delivered (range)† . | No. that received at least 80% of the maximum total dose (%) . | No. that received at least 100% of the minimum* total dose (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Induction (n = 121)‡ | |||||

| Idarubicin, mg/m2 | 121 | 24-48§/NA¶ | 47.5 (22.2-52.4) | 118 (97) | NA |

| ATRA, mg/m2 | 118 | 1620/850 | 1584.2 (136.1-1988.1) | 106 (90) | 112 (95) |

| ATO, mg/kg | 117 | 4.2/2.08 | 4.03 (0-4.94) | 84 (72) | 109 (93) |

| Consolidation cycle 1 (n = 112) | |||||

| ATRA, mg/m2 | 110 | 1260/650 | 1269.8 (515.9-2655.0) | 108 (98) | 108 (98) |

| ATO, mg/kg | 109 | 4.2/2.08 | 4.2 (1.97-4.72) | 100 (92) | 108 (99) |

| Consolidation cycle 2 (n = 112) | |||||

| ATRA, mg/m2 | 109 | 945/475 | 948.4 (522.6-1260.0) | 106 (97) | 109 (100) |

| ATO, mg/kg | 111 | 3.75/1.84 | 3.75 (1.66-4.48) | 100 (90) | 110 (99) |

Protocol-specified dose reductions for ATRA (25 mg/m2/d) and ATO (0.08 mg/kg/d), and omission of up to 2 days per cycle for both drugs were permitted according to clinical circumstances.

In each cycle, 1%-3% of patients received more than 110% of the maximum specified doses due to protocol deviations.

Induction dose delivery data excludes the 3 patients who died prior to commencement of ATO therapy (day 9).

Idarubicin dosing was age adjusted (Table 1).

Not applicable (NA) because there was no protocol-specified minimum idarubicin dose (apart from dose reduction for age > 60).

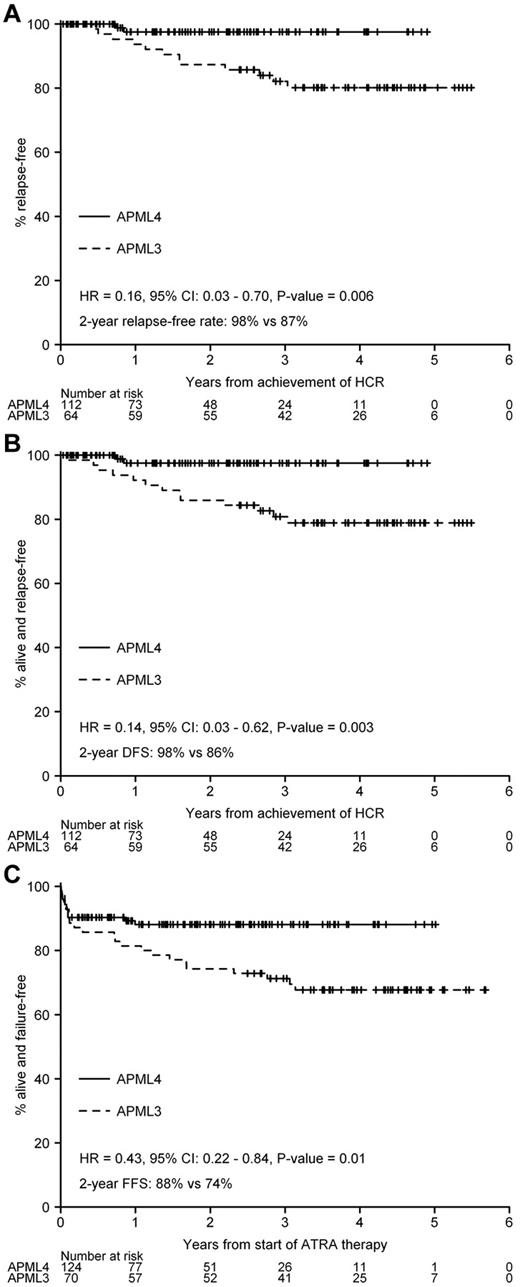

Comparison with APML3 historic control data

There were no statistically significant differences in age, sex distribution, median WBC count, median platelet count, Sanz risk classification, or FLT3 mutation status between the APML3 and APML4 cohorts (Table 2). The difference in early death rate between the 2 studies (7.1% in APML3 and 3.2% in APML4) was not statistically significant (P = .29), nor was the difference in OS (hazard ratio = 0.47, 95% CI, 0.18-1.23, P = .12; APML4 93% vs APML3 90% at 2 years). In contrast, we observed statistically significant improvements in FFR, DFS, and FFS associated with the use of frontline ATO (APML4) compared with APML3 (Figure 3A-C).

Comparison of APML4 with APML3 (historic control). (A) FFR. (B) DFS. (C) FFS.

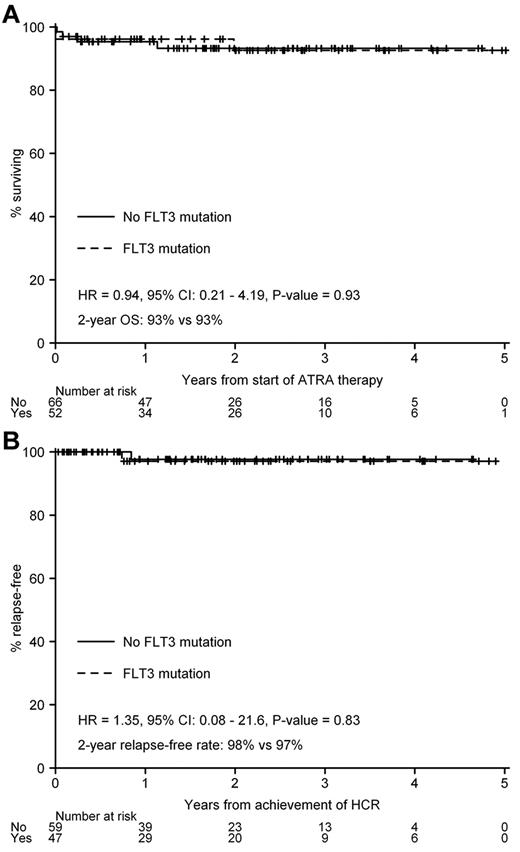

In APML3, FLT3 mutation status was the most important predictor of OS (P = .005), and this association with inferior OS was true for both ITDs and codon 835/836 mutations.16 However, in APML4, OS did not differ by FLT3 mutation status (P = .93, Figure 4A), nor was there any impact on FFR (P = .83, Figure 4B) or FFS (P = .98).

Discussion

The potential mechanisms of the striking antileukemic activity of ATO in APL have been studied extensively. ATO can induce both differentiation and apoptosis of APL cells in a dose-dependent manner.20 Furthermore, ATO has potent and relatively selective activity against APL-initiating cells as a result of its ability to induce PML-RARA fusion protein degradation.5,21 ATO is universally recognized as the treatment of choice for patients who relapse after initial therapy with ATRA and chemotherapy,6–8 and in most instances it is active even in patients whose leukemic cells exhibit ATRA and chemotherapy resistance. Several studies have established the activity of ATO in the management of previously untreated patients, including its use as a single agent9,10 in countries where access to both ATRA and chemotherapy is limited, and tetra-arsenic tetra-sulfide (As4S4)22 has also been used successfully as a single agent for the treatment of newly diagnosed and relapsed APL. However, whereas single-agent arsenic is undoubtedly effective, outcomes with this approach do not appear to be superior to those achieved by protocols using the combination of ATRA with anthracycline-based chemotherapy (Table 6). Synergism of ATO and ATRA has been demonstrated in a mouse model of human APL,23 and has been clinically confirmed in a small randomized trial.24 Because the benefit of ATO is now well established, identification of the optimal way in which it can be incorporated into frontline therapy remains one of the major challenges in the treatment of APL.

Comparison of treatment regimens and outcomes for representative contemporary protocolsa

| Reference . | No. (age restriction) . | Median followup, y . | No. of arsenic treatment daysb . | Idarubicin equivalent, mg/m2c . | Cytarabine, g/m2b . | Other cytotoxic agents in induction and/or consolidation . | OSd . | DFSd . | EFSd . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adès (APL 2000)28 | 178 (< 65) | 5.2 | 99 | 10.8-22.8e | 94% (3 y) | 86% (3 y) | |||

| Sanz (LPA 2005)3 | 402 | 2.3 | 105-125e | 0-5.8e | 88% (4 y) | 90% (4 y) | |||

| Lo Coco (AIDA 2000)4 | 445 (< 62) | 4.9 | 121.7 | 0-6.3e | Etoposidef 6-thioguaninef | 87% (6 y) | 86% (6 y) | ||

| Matthews (Vellore)9 | 72 | 5.0 | 112-158 | Hydroxyureag Low-dose anthracyclineg | 74% (5 y) | 80% (5 y) | 69% (5 y) | ||

| Ghavamzadeh (Tehran)10 | 197 | 3.2 (patients in CR) | 58-142h | Hydroxyureag | 64% (5 y) | 67% (5 y) | |||

| Lu (Beijing)22 i | 19 | 1.1 | 546-597 | 77% (3 y) | |||||

| Powell (North American Intergroup C9710)13 | 243 | 2.4 | 50 | 100 | 1.4 | Hydroxyureag | 86% (3 y) | 90% (3 y) | 80% (3 y) |

| Gore (Baltimore)25 | 45 | 2.7 | 30 | 72 | 2.0 | Hydroxyureag | 88% (3 y) | 89% (3 y) | 76% (3 y) |

| Hu (Shanghai)11 | 85 | 5.8 | 175 | 81 | 17.7-26.7e | Hydroxyureag Idarubicin + cytarabineg Homoharringtoninej | 92% (5 y) | 95% (5 y)k | 89% (5 y) |

| Dai (Changsha)26 j | 90 | 2.7 | 68-84 | 135 | 2.6-3.6e | Hydroxyureag Homoharringtonineg,j | 93% (2.5 y) | ||

| Ravandi (Houston)12 | 82 | 1.9 | 99-110h | Gemtuzumab ozogamicing | 85% (3 y) | 81% (3 y)m | |||

| Iland APML4 (current study) | 124 | 2.0 | 81 | 48 | 93% (2 y) | 98% (2 y) | 88% (2 y) |

| Reference . | No. (age restriction) . | Median followup, y . | No. of arsenic treatment daysb . | Idarubicin equivalent, mg/m2c . | Cytarabine, g/m2b . | Other cytotoxic agents in induction and/or consolidation . | OSd . | DFSd . | EFSd . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adès (APL 2000)28 | 178 (< 65) | 5.2 | 99 | 10.8-22.8e | 94% (3 y) | 86% (3 y) | |||

| Sanz (LPA 2005)3 | 402 | 2.3 | 105-125e | 0-5.8e | 88% (4 y) | 90% (4 y) | |||

| Lo Coco (AIDA 2000)4 | 445 (< 62) | 4.9 | 121.7 | 0-6.3e | Etoposidef 6-thioguaninef | 87% (6 y) | 86% (6 y) | ||

| Matthews (Vellore)9 | 72 | 5.0 | 112-158 | Hydroxyureag Low-dose anthracyclineg | 74% (5 y) | 80% (5 y) | 69% (5 y) | ||

| Ghavamzadeh (Tehran)10 | 197 | 3.2 (patients in CR) | 58-142h | Hydroxyureag | 64% (5 y) | 67% (5 y) | |||

| Lu (Beijing)22 i | 19 | 1.1 | 546-597 | 77% (3 y) | |||||

| Powell (North American Intergroup C9710)13 | 243 | 2.4 | 50 | 100 | 1.4 | Hydroxyureag | 86% (3 y) | 90% (3 y) | 80% (3 y) |

| Gore (Baltimore)25 | 45 | 2.7 | 30 | 72 | 2.0 | Hydroxyureag | 88% (3 y) | 89% (3 y) | 76% (3 y) |

| Hu (Shanghai)11 | 85 | 5.8 | 175 | 81 | 17.7-26.7e | Hydroxyureag Idarubicin + cytarabineg Homoharringtoninej | 92% (5 y) | 95% (5 y)k | 89% (5 y) |

| Dai (Changsha)26 j | 90 | 2.7 | 68-84 | 135 | 2.6-3.6e | Hydroxyureag Homoharringtonineg,j | 93% (2.5 y) | ||

| Ravandi (Houston)12 | 82 | 1.9 | 99-110h | Gemtuzumab ozogamicing | 85% (3 y) | 81% (3 y)m | |||

| Iland APML4 (current study) | 124 | 2.0 | 81 | 48 | 93% (2 y) | 98% (2 y) | 88% (2 y) |

References 3, 4, and 28 are ATRA/chemotherapy protocols; references 9, 10, and 22 are single-agent arsenic protocols (ATO or As4S4); references 13 and 25 are ATRA/chemotherapy protocols with ATO in consolidation; references 11 and 26 are ATRA/ATO/chemotherapy protocols; and reference 12 is an ATRA/ATO protocol with gemtuzumab ozogamicin for high-risk patients.

Data for arsenic exposure (ATO or As4S4) include amounts used in induction, consolidation, and (where appropriate) maintenance; data for idarubicin equivalent and cytarabine doses include amounts used in induction and consolidation.

Idarubicin equivalent calculated as follows41 : 10 mg of idarubicin = 12 mg of mitoxantrone = 50 mg of daunorubicin.

OS: overall survival; DFS: disease-free survival; EFS: event-free survival; survival data are single time-point figures at the times shown in parentheses.

Higher dose for high-risk patients, except LPA 2005, in which the intermediate-risk group received the highest idarubicin equivalent dose of anthracycline (idarubicin) plus anthraquinone (mitoxantrone).

Additional chemotherapy during consolidation for high-risk patients.

Additional chemotherapy during induction for high-risk patients.

Based on median number of days to CR = 30.

This study used single-agent As4S4 rather than ATO.

Additional chemotherapy during consolidation for all patients.

Data were reported as RFS with no deaths in CR and are therefore included as DFS here.

Results shown are for the group B1 patients who received ATRA and ATO during induction; the total cytarabine dose ranged from 4.5-6.3 g and has been adjusted for an average body surface area of 1.73 m2.

EFS in this series was measured from the date of CR until relapse or death and is therefore listed here as DFS.

The North American Leukemia Intergroup Study C971013 demonstrated that the addition of 2 cycles of ATO to ATRA and chemotherapy during consolidation significantly improved event-free survival. In a similar ATRA and chemotherapy protocol, postinduction ATO has been used as a substitute for the second cycle of consolidation chemotherapy.25 The Shanghai11 and Changsha26 groups have also demonstrated excellent outcomes with ATRA- and ATO-based induction therapy, although both studies variably used additional cytotoxic agents during induction for high-risk patients. In addition, both studies used substantial postremission chemotherapy (daunorubicin, cytarabine, and homoharringtonine) in multiple cycles of consolidation (Table 6). In contrast, we attempted to maximize antileukemic activity during induction by adding ATO to ATRA and idarubicin in the APML4 protocol, and also omitted all other chemotherapeutic agents from consolidation. This approach has proven extremely successful, with DFS and OS in the APML4 study reported here that compare favorably with other published data (Table 6). Furthermore, the APML4 results have been achieved at relatively low cumulative ATO and anthracycline exposures and without the use of other chemotherapeutic agents that have been advocated recently for high-risk patients,3,27,28 such as intermediate- or high-dose cytarabine. Although the median followup in this interim analysis is relatively short, it is comparable with several other studies with a median followup that was less than 3 years at the time of reporting.3,12,13,22,25,26 Nevertheless, we recognize that additional relapses are likely to be seen with a longer period of observation, and a final APML4 analysis will be performed when the last registered patient has been followed for a minimum of 2 years after consolidation.

The strategy that most closely resembles APML4 was reported by investigators at the MD Anderson Cancer Center.12 They omitted anthracycline chemotherapy entirely, using only ATRA and ATO in both induction and consolidation, although gemtuzumab ozogamicin was added for patients with high-risk disease. The OS and DFS data reported herein with APML4 are at least as good as the MD Anderson data (Table 6) despite the use of less ATO and a similar median duration of follow-up, suggesting that some anthracycline in induction is beneficial in maximizing long-term outcomes. Because gemtuzumab ozogamicin is no longer readily accessible after its voluntary withdrawal from the market, the combination of idarubicin with ATO and ATRA in induction represents a highly effective and readily available therapeutic approach, especially for patients with high-risk disease.

The potent antileukemic activity of ATO-based combination therapy is particularly evident when FLT3 mutation data are taken into account. Although the prognostic impact of FLT3 mutations in APL has been more controversial than in non-APL acute myeloid leukemia, a large meta-analysis29 encompassing 1063 patients with APL identified FLT3 ITDs as being significantly associated with inferior OS and DFS, and a trend toward adverse outcomes was also observed for patients with codon 835 mutations. An association between WBC count and FLT3 ITDs was noted in that study,29 and it is not entirely clear whether the adverse impact of FLT3 mutations was independent of WBC count. However, it is interesting to note that 10 of the 11 reports that were included in that meta-analysis used ATRA plus chemotherapy. The final study showing no association between FLT3 mutations and adverse outcomes was a study of single-agent ATO.30 In our previous study of ATRA and idarubicin (APML3),16 our FLT3 mutation data were in close agreement with the meta-analysis, because FLT3 mutation status was the single most important predictor of OS in multivariate analysis and the association with inferior survival persisted when ITD and codon 835/836 mutations were assessed separately. Furthermore, FLT3 mutations also emerged as important predictors of remission duration and DFS in multivariate analyses when maintenance components were treated as time-dependent covariates. In contrast, the OS and FFR curves that we have observed in the current APML4 study for FLT3 wild-type and mutant subgroups are superimposable (Figure 4A-B). Therefore, any adverse effect of FLT3 mutations that is evident when APL is treated with ATRA plus chemotherapy appears to be abrogated by inclusion of ATO during induction and consolidation. Accordingly, despite the frequent occurrence of FLT3 mutations in APL, it is highly unlikely that FLT3 inhibitor therapy will have any role in the future management of APL.

The early death rate is typically identified as 5%-10% in most studies of APL, although it is undoubtedly higher in population-based studies,31,32 indicating that selection bias is inevitable in APL trials. Whereas the same criticism can be directed at the present study, the low early death rate (3.2%) likely also reflects better supportive care during induction. In contrast to APML3, where hemostatic targets were not protocol specified and hemostatic support was administered according to local practice, APML4 used clear recommendations to maintain adequate hemostasis (Table 1). In addition, all patients in APML4 received prophylactic prednisone33 to minimize the frequency and severity of DS regardless of pretreatment WBC count, whereas in APML3, prednisone was only used if the WBC count exceeded 10 × 109/L during induction or once clinical features of DS were present. DS was a contributory factor in the early deaths of 2 patients in the APML3 study, whereas there were no fatalities due to DS in APML4. Therefore, although the induction protocol in APML4 was more intensive than that in APML3, a trend toward lower early deaths was evident and most likely reflects improved supportive care.

Because both idarubicin and ATO are potentially cardiotoxic, in the present study we delayed initiation of ATO until day 9, after the fourth and final dose of idarubicin. Strict attention to electrolyte levels was specified in the protocol, and no instances of torsades de pointes or other life-threatening arrhythmias occurred during induction despite 14% of patients experiencing Q-Tc prolongation to > 500 milliseconds on at least 1 occasion. It is likely that the use of oral ATO34,35 will reduce the risk of significant arrhythmias, especially when administered during consolidation, when outpatient therapy is desirable and feasible.

A second reason for delaying commencement of ATO until day 9 was to reduce the risk and severity of DS. Whereas DS is typically seen with ATRA therapy, ATO can also cause an identical syndrome,36 so we delayed ATO until the protective cytoreductive effect of idarubicin chemotherapy was manifest. We also used prednisone prophylaxis in all patients, regardless of initial WBC count, to further reduce DS complications. Although the routine use of prophylactic corticosteroids has not been shown conclusively to prevent DS,8 there is some evidence33 suggesting that they may be beneficial in patients receiving ATRA-based induction. Because our patients received both ATRA and ATO, we felt that the potential benefits of short-term prophylactic prednisone outweighed any potential risks, and the absence of early deaths attributable to either DS or corticosteroid toxicity appears to have vindicated that decision. Furthermore, it is worth noting that of the 4 early deaths in this study, 3 occurred before day 9 when ATO therapy was initiated, and ATO was not implicated in any of the other 3 deaths that occurred beyond day 36. Accordingly, only 1 of 7 deaths in our series of 124 patients was potentially associated with ATO toxicity, and we believe this highlights the lack of safety concern associated with the incorporation of ATO in the regimen described herein.

The optimal number of consolidation cycles required to maximize FFR is unknown, and the number incorporated into currently used regimens is quite variable among the protocols listed in Table 6, ranging from 2-9. In APML4, only 2 cycles were used, further emphasizing the value of arsenic-based consolidation, because our results for DFS are not inferior to protocols incorporating 3 or more cycles of chemotherapy-based consolidation. Whereas our dose-delivery data demonstrate the feasibility of the APML4 regimen, logistic issues associated with repeated IV infusions of ATO constitute a relative disadvantage. Adopting an intermittent ATO schedule (5 days per week for 5 weeks) for both APML4 consolidation cycles would reduce toxicity, improve resource utilization, and be more palatable for patients. Whether this would compromise outcomes is unknown, but any impact on efficacy is likely to be small. Alternatively, provided that pharmacologic and therapeutic equivalence were established, oral rather than IV ATO would significantly facilitate administration, but assuring protocol adherence would be more difficult, as seen with other long-term oral anticancer therapies.37

Based on the benefits of maintenance that were observed in our previous APML3 study,16 maintenance with ATRA, oral MTX, and 6MP was administered to all patients in APML4. The role of maintenance, however, remains controversial, because there are conflicting data from randomized studies. Maintenance treatment was associated with significantly better outcomes in both the European APL9338 and North American Intergroup APL39 studies, whereas the AIDA 049340 report from GIMEMA showed no advantage for maintenance. All of these studies were based on an ATRA/chemotherapy backbone, and it would be appropriate to reexamine the requirement for maintenance in the era of ATO-based therapy for newly diagnosed patients with APL.

In summary, APML4 induction therapy, which uses the 3 most active agents in APL (ATRA, idarubicin, and ATO) combined with consolidation restricted to ATRA and ATO, is capable of achieving excellent DFS and OS. The total doses of anthracycline and ATO used in the present study are at the low end of the spectrum of studies that have been associated with DFS in excess of 90% (Table 6), and APML4 is further characterized by the omission of any other cytotoxic agents during consolidation. The toxicity profile is manageable, and the lack of deaths associated with consolidation therapy is a major advantage compared with protocols that use intensive postremission chemotherapy. Furthermore, the toxicity associated with the APML4 protocol is theoretically capable of further attenuation by the use of a risk-adapted reduction in idarubicin dose during induction, the incorporation of oral ATO during consolidation, and possibly reduction or elimination of maintenance. Our experience with APML4 adds further support to the use of ATRA and ATO as initial therapy for APL in both induction and consolidation, with minimal requirement for additional chemotherapy.

There is an Inside Blood commentary in this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Andrew Wei (ALLG Acute Leukaemia and Myelodysplasia Disease Group Chair) for helpful comments regarding the manuscript; Richard Fisher and Jenny Beresford (Centre for Biostatistics and Clinical Trials) for assistance with the statistical analysis; and the nurses, data coordinators, and patients who participated. The following members of ALLG and Australian & New Zealand Children's Haematology/Oncology Group contributed patients to the APML4 study: B. Augustson, J. Bashford, K. Bavishi, R. Bell, W. Benson, R. Bird, K. Bradstock, P. Campbell, P. Cannell, D. Carney, K. Cartwright, L. Coyle, P. Crispin, G. Cull, I. Cunningham, J. Curnow, M. Dean, S. Deveridge, S. Dunkley, P. Eliadis, A. Enjeti, A. Enno, J. Estell, H. Fairweather, K. Fay, R. Filshie, F. Firkin, C. Fraser, T. Frost, J. Gibson, P. Giri, M. Greenwood, A. Grigg, U. Hahn, M. Hertzberg, L. L. Ho, P. J. Ho, C.-H. Hui, H. J. Iland, I. Irving, A. Johnston, I. Kerridge, J. Koutts, H. C. Lai, S. Larsen, G. Lieschke, R. Lowenthal, S. Milliken, J. Moore, E. Morris, J. Morton, H. Nandurkar, J. Norman, N. Patton, M. Pidcock, I. Prosser, W. Rasheed, A. Roberts, M. Roberts, J. Robilliard, D. Ross, P. Rowlings, M. Seldon, A. Spencer, M. Stevens, W. Stevenson, J. Szer, J. Taper, K. Taylor, P. Thompson, C. Tiley, J. Trotman, C. Turtle, C. Ward, A.-M. Watson, A. Wei, and D. Westerman.

The molecular monitoring was supported in part by a grant from the Leukaemia Foundation of Australia. Phebra provided ATO for the entire study.

Authorship

Contribution: H.J.I. was the principal investigator and takes primary responsibility for the manuscript; H.J.I., K.B., M.H., P.B., F.F., J.R., and J.F.S. designed the study; H.J.I., K.B., M.H., A.G., F.F., C.T., K.T., R.F., M.S., J.T., J.S., J.M., J.B., and J.F.S. recruited the patients; S.G.S., A.C., and A.H. performed the laboratory work; H.J.I., M.C., J.R., and J.D.I. performed the data validation and interpretation; M.C. performed the statistical analysis; H.J.I., M.C., and J.F.S. wrote the manuscript; and all authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: H.J.I., F.F., and J.F.S. served as consultants for Phebra. Apart from the provision of ATO, Phebra had no involvement in APML4 trial design, conduct of the trial, data analysis, or preparation of the manuscript. J.R. served as a statistician for the ALLG during the APML4 study, but has since joined Novartis (ATRA, idarubicin, and ATO are not Novartis products). The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Harry Iland, Institute of Haematology, Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Missenden Road, Camperdown, New South Wales, Australia 2050; e-mail: harryiland@gmail.com.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal