Abstract

There is evidence suggesting that N-cadherin expression on osteoblast lineage cells regulates hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) function and quiescence. To test this hypothesis, we conditionally deleted N-cadherin (Cdh2) in osteoblasts using Cdh2flox/flox Osx-Cre mice. N-cadherin expression was efficiently ablated in osteoblast lineage cells as assessed by mRNA expression and immunostaining of bone sections. Basal hematopoiesis is normal in these mice. In particular, HSC number, cell cycle status, long-term repopulating activity, and self-renewal capacity were normal. Moreover, engraftment of wild-type cells into N-cadherin–deleted recipients was normal. Finally, these mice responded normally to G-CSF, a stimulus that mobilizes HSCs by inducing alterations to the stromal micro-environment. In conclusion, N-cadherin expression in osteoblast lineage cells is dispensable for HSC maintenance in mice.

Introduction

Osteoblast lineage cells have been shown to play an important role in regulating hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs),1-3 and there is intense interest in identifying HSC regulatory molecules they produce. Cadherins are cell-cell adhesion molecules, which play a crucial role in the regulation of Drosophila stem cell niches,4 and given that osteolineage cells express several cadherins,5 it is hypothesized that cadherins may play a role in regulating mammalian hematopoiesis. Indeed, it has been reported that HSCs lie adjacent to spindle-shaped N-cadherin+ osteoblasts (SNO cells),3 and purified HSCs home to SNO cells in irradiated recipients.6 It was thus proposed that N-cadherin expressed on HSCs tethers them to N-cadherin expressed on osteoblasts. Consistent with this possibility, human CD34+ cells appear to anchor themselves to stromal cells through homotypic N-cadherin junctions in vitro.7

The role that N-cadherin plays in the regulation of hematopoiesis is controversial. Indeed, there are conflicting results as to whether N-cadherin protein is expressed in HSCs,6-9 although a recent study by Hosokawa et al convincingly showed that N-cadherin mRNA is present in phenotypic murine HSCs.10 Genetic deletion of Cdh2 (encoding N-cadherin) from HSCs results in no observable hematopoietic phenotype.9 In contrast, silencing of N-cadherin using shRNA10 or a dominant negative protein11 results in loss of HSC quiescence and repopulating activity. N-cadherin is thought to form homodimers with N-cadherin molecules expressed on other cells, although it has also been described to interact with other cadherins, such as E-cadherin,12-14 C-cadherin,12 and R-cadherin15 as well as noncadherins, such as KLRG1.16 Thus, it is possible that expression of other cadherins in HSCs may compensate for the loss of N-cadherin.

Rather than attempt to reconcile the conflicting results involving N-cadherin expression and function in HSCs, we chose to investigate what role osteolineage production of N-cadherin plays in the regulation of hematopoiesis. Because Cdh2−/− mice die during early embryogenesis,17 we used a conditional knockout strategy to delete Cdh2 from osteolineage cells, including SNO cells. We show that loss of N-cadherin expression from osteolineage cells has no impact on basal hematopoiesis or HSC function.

Methods

Mice

Cdh2flox [B6.129S6(SJL)-Cdh2tm1Glr/J],18 Osx-Cre [B6.Cg-Tg(Sp7-tTA,tetO-EGFP/cre)1Amc/J],19 and wild-type (WT) mice that have the Ly5.1 gene (B6.SJL-Ptprca Pepcb/BoyJ) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Cdh2flox mice were backcrossed to more than 99% congenic with the C57BL/6 background as verified by microsatellite analysis performed by the Rheumatic Disease Core Center for Speed Congenics (Washington University). Mixed-strain mT/mG mice20 were a gift from Dr Fanxin Long (Washington University). Mixed strain Osx-Cre mice were used as controls for the micro-CT analysis. Age- (6-8 weeks) and sex-matched mice were used in all experiments. All mice were maintained under specific pathogen free conditions according to methods approved by the Washington University Animal Studies Committee.

Bone microstructure

For analysis of bone microstructure and mineralization, animals were subjected to in vivo scanning using micro-CT (VIVA CT 40, Scanco Medical AG), using previously described methods.21,22 Briefly, with the animal under isoflurane (1%-2%) anesthesia, one leg was immobilized in a custom-made fixture. Scans included 100 slices encompassing the proximal epiphysis and metaphysis of the tibia, and 25 slices of the diaphysis 5 mm proximal to the tibia-fibular junction. Scans were performed at 21.5 μm voxel resolution, 109 μA current, and 70 kEV. The metaphysis was analyzed for trabecular bone volume/tissue volume and tissue mineral density; the volumetric density of the trabecular fraction. In the diaphyseal scans, marrow area and tissue area were determined.

Bone marrow, blood, and spleen analysis

Bone marrow cells were obtained by flushing isolated femurs with 1 mL of PBS supplemented with 10% FCS. Blood, bone marrow, and spleen cells were quantified using a Hemavet automated cell counter (CDC Technologies).

Bone marrow transplantation

For competitive transplantation, bone marrow cells from WT Ly5.1/5.2-expressing mice were mixed at a 1:1 ratio with marrow from experimental (Cdh2flox/flox Osx-Cre) or control mice (Cdh2flox/flox) expressing the Ly5.2 locus. At least 2 donor mice of each genotype were pooled for each experiment. A total of 2 × 106 cells injected retro-orbitally into lethally irradiated (1000 cGy) WT Ly5.1-expressing mice. For secondary transplants, bone marrow from primary recipients was pooled, and 2 × 106 cells were transplanted into irradiated Ly5.1 expressing WT mice. For engraftment experiments, 2 × 106 bone marrow cells from mice expressing the Ly5.1 locus were transplanted into lethally irradiated experimental (Cdh2flox/flox Osx-Cre) or control (Cdh2flox/flox) mice expressing the Ly5.1 locus. Antibiotics (trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; Alpharma) were given for 2 weeks after transplantation.

Flow cytometry

Red blood cells in peripheral blood and bone marrow mononuclear cell preparations were lysed in Tris-buffered ammonium chloride (pH 7.2) buffer and incubated with the indicated antibody at 4°C for 30 minutes in PBS containing 0.1% sodium azide, 1mM EDTA, and 0.2% (weight/volume) BSA to block nonspecific binding. All flow cytometry antibodies were purchased from eBioscience unless otherwise stated. For chimerism analysis and analysis of lineage distributions, the following directly conjugated monoclonal antibodies were used: peridinin chlorophyll protein complex (PerCP)–Cy5.5-conjugated Ly5.1 (A20, CD45.1), allophycocyanin (APC)–conjugated Ly5.2 (104, CD45R.2), APC-conjugated CD115 (AFS98, monocytes), FITC-conjugated Ly6C/G (RB6-8C5, Gr-1, myeloid), phycoerythrin (PE)–conjugated CD3e (145-2C11, T lymphocytes), and APC-eFluor780–conjugated CD45R (RA3-6B2, B220, B lymphocytes).

For HSC staining, cells were stained with a cocktail of biotin-conjugated B220, ter119, CD3e, Gr1, and CD41 (MWReg30), PE-conjugated CD150 (TC15-12F12.2; BioLegend), PE-Cy7–conjugated CD48 (HM48-1; BD Biosciences), PerCP-Cy5.5-conjugated Sca1 (D7), APC-conjugated CD117 (2B-8), and APC eFluor-780–conjugated strepavidin. For cell cycle analysis, cells were then fixed using the Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD Biosciences), blocked with 5% goat serum, stained with FITC-conjugated Ki67 (B56, BD Biosciences), and resuspended in 1 mg/mL of 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Invitrogen). For lineage− c-kit+ sca+ (KLS) analysis, cells were stained with a panel of FITC-conjugated lineage markers, PE-conjugated Sca, and APC-conjugated c-kit. Data were collected on a Gallios 10-color, 3-laser flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter) and analyzed with FlowJo Version 9.4.10 software (TreeStar).

Real time quantitative RT-PCR

For the marrow fraction, femurs were flushed with 1 mL of Trizol (Invitrogen). For the bone fraction, femurs were flushed with 1 mL of PBS, the flow-through was discarded, and then the bones were flushed with 1 mL of Trizol. RNA was prepared according to the manufacturer's specifications. One-step quantitative RT-PCR was performed using the TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) using no template and no RT controls. Data were collected on a 7300 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). N-cadherin was detected with custom TaqMan Gene Expression Assay Mixes (Mm0048320, Applied Biosystems). β-actin was detected using forward primer: 5′-ACCAACTGGGACGATATGGAGAAGA-3′; β-actin reverse primer, 5′- TACGACCAGAGGCATACAGGGACAA-3′; and β-actin dT-FAM/TAMRA probe, 5′-AGCCATGTACGTAGCCATCCAGGCTG-3′.

CFU-C assay

We plated 10 μL of blood, 5 × 104 nucleated spleen cells, or 2.0 × 104 nucleated bone marrow cells in 2.5 mL methylcellulose media supplemented with a cocktail of recombinant cytokines (MethoCult 3434; StemCell Technologies). Cultures were plated in duplicate and placed in a humidified chamber with 5% carbon dioxide (CO2) at 37°C. After 7 days of culture, the number of colonies per dish was counted.

G-CSF administration

Recombinant human G-CSF (Amgen) was administered by twice-daily subcutaneous injection at a dose of 125 μg/kg for 7 days. For bone marrow, spleen, and blood KLS numbers, mice were analyzed 2 hours after injections of G-CSF on day 3 or day 7.

5-FU administration

Mice were treated with a single intravenous dose of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU; 150 mg/kg) at day 0 and followed by serial bleeding over 21 days. The absolute neutrophil count was determined by multiplying the percentage of Gr1hi cells in the blood by the white blood count.

Immunofluorescence

Bones were fixed for 24 hours in 10% zinc-buffered formalin, decalcified in dilute formic acid (Immunocal; Decal Chemical Corporation) for 72 hours, and then processed for paraffin embedding. Sections (5μM) were prepared and baked at 37°C for 5 to 7 days to increase section adherence. Sections were then deparaffinized, rehydrated, antigen retrieved at 95°C in citrate buffer, pH 6, for 10 minutes, blocked with 3% H2O2, blocked in TNB buffer provided in the TSA biotin kit (PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences), and then blocked for avidin and biotin using a kit (Vector Labs). Sections were then stained with a polyclonal rabbit anti–human N-cadherin antibody (10 μg/mL, ab18203, Abcam) followed by biotinylated donkey anti–rabbit IgG (2 μg/mL; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories), amplification using the biotinyl tyramide using the kit, and then detection using strepavidin Dylight 594 (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). Green fluorescent protein (GFP) was detected with chicken anti-GFP (2 μg/mL, ab13970; Abcam) followed by Dylight 488–conjugated anti–chicken IgY (2 μg/mL; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). Slides were mounted with Vectashield with DAPI (Vector Labs) and visualized on an Apotome fluorescent microscope (Carl Zeiss) using a 20× (0.8) objective. Images were taken using an Axiiocam MRm camera and analyzed using Axiovision Version 4.8 software (Carl Zeiss). No N-cadherin staining was observed in sections stained with polyclonal rabbit isotype IgG (data not shown). No GFP staining was observed in mice lacking expression of GFP (data not shown). Isotype controls slides demonstrated that dTomato fluorescence was entirely quenched during paraffin embedding (data not shown).

In vitro bone marrow stromal cell differentiation

Bone marrow stromal cells were isolated by removing the distal epiphyses, centrifuging the bone at 15.7g for 15 seconds, and then processing for culture as described.23 Bone marrow stromal cell cultures were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 in ascorbic acid free α-MEM (Invitrogen) with 20% FCS, 40mM l-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin-G, and 100 mg/mL streptomycin. For mineralization, bone marrow stromal cells were seeded in a 6-well plate at 400 000 cells per well and cultured for 25 days in media with mineralization cocktail (50μM ascorbic acid and 10μM β-glycerophosphate). Samples were collected every 5 days by scraping the cells in cold PBS. Whole cell lysates for Western blot analysis were made by spinning cells down at 0.8g for 5 minutes and resuspending them in RIPA buffer. A total of 5 μg of total protein was loaded on NuPAGE gel (4%-12%; Invitrogen) and separated by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis. Transferred proteins were revealed using anti–β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich), anti–N-cadherin (BD Transduction Laboratories), and anti-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase (GeneTex).

Statistics

Statistical significance of differences was calculated using 2-tailed Student t tests (assuming equal variance) or 1- or 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni posttesting. P values less than .05 were considered significant. All data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Results

N-cadherin is efficiently deleted from osteolineage cells in Cdh2flox/flox Osx-Cre mice

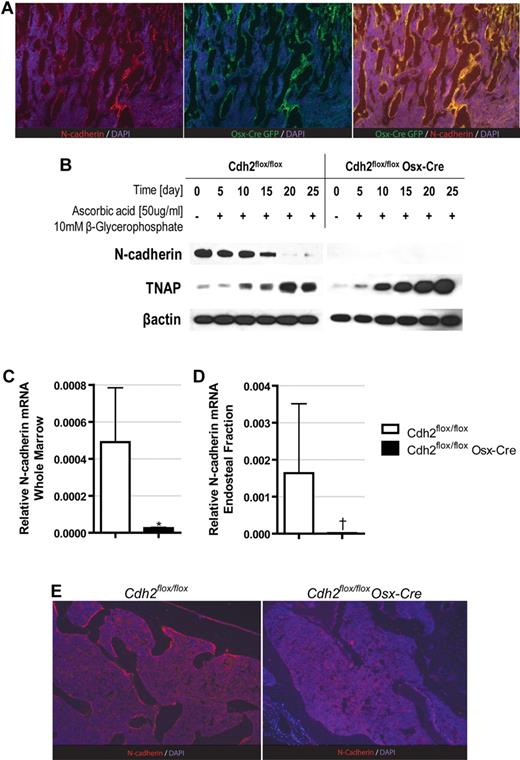

Because SNO cells have been shown to express the early osteoblast transcription factor osterix,6 we chose to use transgenic mice expressing cre-recombinase (Cre) driven by the osterix promoter (Osx-Cre mice) to delete Cdh2. To confirm that SNO cells are targeted by Osx-Cre, we first performed lineage mapping using the mT/mG reporter mice, in which Cre-mediated recombination results in expression of GFP. As reported previously,6 N-cadherin expression was readily detected in endosteal osteoblasts in the trabecular region, with lower expression in osteoblasts in the diaphysis; no N-cadherin expression was detected in hematopoietic cells in the bone marrow or periosteal osteoblasts (Figure 1A). Importantly, GFP expression in the mT/mG Osx-Cre mice mirrored that of N-cadherin, demonstrating that N-cadherin is almost exclusively expressed in cells targeted by Osx-Cre.

N-cadherin expression is efficiently ablated in osteoblast lineage cells in Osx-Cre Cdh2flox/flox mice. (A) Representative photomicrographs of bone sections from mT/mG Osx-Cre mice stained for N-cadherin (red), GFP (green), and DAPI (blue). (B) Primary bone marrow stromal cells were differentiated toward the osteoblast lineage, and Western blots were performed for N-cadherin, tissue nonspecific alkaline phosphatase (TNAP), and β-actin. (C-D) RNA was isolated from total bone marrow (C) or the endosteal bone marrow fraction (D), and N-cadherin mRNA expression relative to β-actin expression was determined by real-time RT-PCR. Data are the mean ± SEM of 5 mice. *P = .002. †P = .007. (E) Representative photomicrographs of bone sections stained for N-cadherin (red) and DAPI (blue). Images are representative of 3 independent experiments (original magnification ×20).

N-cadherin expression is efficiently ablated in osteoblast lineage cells in Osx-Cre Cdh2flox/flox mice. (A) Representative photomicrographs of bone sections from mT/mG Osx-Cre mice stained for N-cadherin (red), GFP (green), and DAPI (blue). (B) Primary bone marrow stromal cells were differentiated toward the osteoblast lineage, and Western blots were performed for N-cadherin, tissue nonspecific alkaline phosphatase (TNAP), and β-actin. (C-D) RNA was isolated from total bone marrow (C) or the endosteal bone marrow fraction (D), and N-cadherin mRNA expression relative to β-actin expression was determined by real-time RT-PCR. Data are the mean ± SEM of 5 mice. *P = .002. †P = .007. (E) Representative photomicrographs of bone sections stained for N-cadherin (red) and DAPI (blue). Images are representative of 3 independent experiments (original magnification ×20).

We next intercrossed Osx-Cre mice with Cdh2flox/flox mice18 to generate Cdh2flox/flox Osx-Cre mice. Mutant mice were born at Mendelian frequency and had no outward observable phenotype aside from a 5% to 10% reduction in size (data not shown). The conditional Cdh2 allele contains loxP sites surrounding exon 1 of the gene, which includes not only the translational start site but also approximately 1 kb upstream of the exon. We thus would predict that conditional deletion of Cdh2 would remove both the translational start site and several transcriptional elements important for mRNA expression. We first tested N-cadherin deletion using in vitro osteoblastic differentiation of primary bone marrow stromal cells. Consistent with previously reported data,21 in WT controls, N-cadherin is expressed at high levels early during culture, but its expression decreases as the cells mature and express osteoblast-specific genes, such as tissue nonspecific alkaline phosphatase. In contrast, N-cadherin–deleted mice show no expression of N-cadherin at baseline or on differentiation (Figure 1B). Indeed, when examined in vivo, N-cadherin mRNA expression in total bone marrow was reduced 20-fold compared with control mice (Figure 1C). To assay the level of N-cadherin expression in the osteoblast compartment, we then prepared mRNA from the bone fraction by first flushing the bones with PBS, discarding the flow-through, and then flushing the bones with Trizol, a method that highly enriches for osteoblasts.24 As shown in Figure 1D, this fraction was highly enriched for N-cadherin mRNA and demonstrated a 132-fold loss of N-cadherin in Cdh2flox/flox Osx-Cre mice. Finally, to demonstrate loss of the N-cadherin protein specifically in osteoblasts, we performed immunostaining for N-cadherin on bone sections from Cdh2flox/flox Osx-Cre mice, using the highly sensitive tyramide amplification system to detect any residual low levels of N-cadherin. Whereas N-cadherin expression in osteoblasts was readily detected in control animals, no N-cadherin expression was detected in Cdh2flox/flox Osx-Cre mice (Figure 1E). These data demonstrate that N-cadherin is efficiently deleted in osteoblasts using the Osx-Cre.

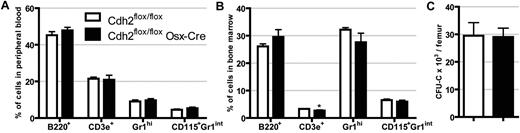

Basal hematopoiesis is normal in mice lacking osteoblast N-cadherin

To assess the contribution of osteoblast N-cadherin to hematopoiesis, we first analyzed blood and bone marrow from Cdh2flox/flox Osx-Cre mice and compared them with Cdh2flox/flox controls. No difference in peripheral white blood cells, red blood cells, or platelet counts was observed (Table 1). Likewise, bone marrow cellularity and spleen size were similar. Moreover, the relative percentage of granulocytes, monocytes, B cells, and T cells in the blood and bone marrow were similar (Figure 2A-B). Finally, the number and cytokine responsiveness of lineage-committed progenitors, as measured using the CFU-C assay, were similar between Cdh2flox/flox Osx-Cre and control mice (Figure 2C). Together, these data show that basal hematopoiesis is normal in mice lacking N-cadherin expression in osteolineage cells.

Baseline hematopoietic parameters

| Organ . | Parameter . | Unit . | Cdh2flox/flox . | Cdh2flox/flox Osx-Cre . | n . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood | WBC | × 103/μL | 9.47 ± 1.02 | 11.70 ± 0.96 | 10-17 | .52 |

| RBC | × 106/μL | 8.82 ± 0.39 | 9.05 ± 0.17 | 7-17 | .52 | |

| MCV | fL | 48.96 ± 0.82 | 48.06 ± 0.53 | 7-17 | .37 | |

| Platelets | × 103/μL | 649.30 ± 31.05 | 694.80 ± 36.57 | 7-17 | .46 | |

| Bone marrow | Cellularity | × 106/femur | 22.68 ± .95 | 19.60 ± 1.83 | 15-29 | .1 |

| Spleen | Cellularity | × 106/spleen | 71.85 ± 7.00 | 88.38 ± 6.06 | 16-26 | .46 |

| Organ . | Parameter . | Unit . | Cdh2flox/flox . | Cdh2flox/flox Osx-Cre . | n . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood | WBC | × 103/μL | 9.47 ± 1.02 | 11.70 ± 0.96 | 10-17 | .52 |

| RBC | × 106/μL | 8.82 ± 0.39 | 9.05 ± 0.17 | 7-17 | .52 | |

| MCV | fL | 48.96 ± 0.82 | 48.06 ± 0.53 | 7-17 | .37 | |

| Platelets | × 103/μL | 649.30 ± 31.05 | 694.80 ± 36.57 | 7-17 | .46 | |

| Bone marrow | Cellularity | × 106/femur | 22.68 ± .95 | 19.60 ± 1.83 | 15-29 | .1 |

| Spleen | Cellularity | × 106/spleen | 71.85 ± 7.00 | 88.38 ± 6.06 | 16-26 | .46 |

Data are mean ± SEM.

WBC indicates white blood cells; RBC, red blood cells; and MCV, mean corpuscular volume.

Basal hematopoiesis is normal in N-cadherin–deleted mice. The percentage of B cells (B220+), T cells (CD3e+), neutrophils (Gr-1hi), and monocytes (CD115+ Gr-1int) in the blood (A) and bone marrow (B). Data are the mean ± SEM of 12 to 14 mice. *P = .003. (C) The number of CFU-C in the femur is shown. Data are the mean ± SEM of 4 or 5 mice.

Basal hematopoiesis is normal in N-cadherin–deleted mice. The percentage of B cells (B220+), T cells (CD3e+), neutrophils (Gr-1hi), and monocytes (CD115+ Gr-1int) in the blood (A) and bone marrow (B). Data are the mean ± SEM of 12 to 14 mice. *P = .003. (C) The number of CFU-C in the femur is shown. Data are the mean ± SEM of 4 or 5 mice.

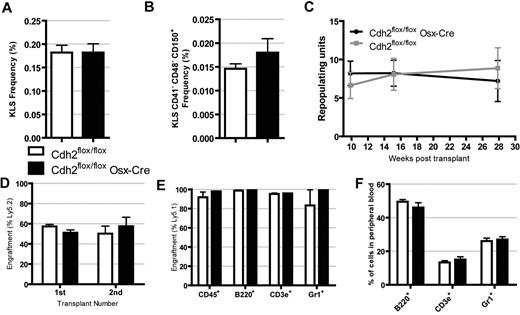

Osteoblast N-cadherin is not required of HSC long-term repopulating activity

To assess the effect of the loss of osteoblast N-cadherin on HSCs, we first quantified the frequency of phenotypic hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in the bone marrow. The frequency of KLS cells, a heterogeneous population containing HSCs and their progenitors, was similar between N-cadherin–deleted and control mice (Figure 3A). Similarly, the frequency of KLS CD41− CD48− CD150+ (KLS SLAM) cells, a cell population highly enriched in HSCs,25 was also similar in N-cadherin–deleted and control mice (Figure 3B). Long-term repopulating activity was assessed using a competitive repopulation assay. Bone marrow cells from Cdh2flox/flox or Cdh2flox/flox Osx-Cre mice were transplanted in an approximately 1:1 ratio with competitor bone marrow cells into lethally irradiated recipients, and donor chimerism was assessed up to 7.5 months after transplantation. No difference in long-term multilineage repopulating activity between N-cadherin–deleted and control cells was observed (Figure 3C). Next, we assessed HSC self-renewal capacity by performing secondary transplantation in a separate cohort of competitively repopulated mice. The percentage of N-cadherin–deleted donor cells in the secondary recipients was similar to that observed in the primary recipients and did not differ significantly from recipients of control cells (Figure 3D). These data show that N-cadherin expression in osteolineage cells is not required for the maintenance of HSC long-term repopulating activity or self-renewal.

HSC number and long-term repopulating activity are normal in N-cadherin–deleted mice. (A) The frequency of KLS cells (n = 5). (B) The frequency of KLS CD41− CD48− CD150+ (KLS SLAM) cells (n = 5). (C) Competitive repopulation assays were performed, and the number of repopulating units was calculated up to 7.5 months after transplantation. Data are representative of 2 independent transplants with n = 4 or 5 mice per group per experiment. (D) Competitive repopulation assays were repeated with N-cadherin–deleted or control cells, and then secondary transplantation was performed after 12 weeks. Shown is the percentage of donor cells in the primary recipients (at 12 weeks) or secondary recipients (at 8 weeks, n = 5). (E-F) Bone marrow cells expressing the Ly5.1 locus were transplanted into irradiated N-cadherin–deleted or control mice. Donor engraftment (E) and lineage distribution (F) in the peripheral blood 38 weeks after transplantation (n = 4). Data are the mean ± SEM.

HSC number and long-term repopulating activity are normal in N-cadherin–deleted mice. (A) The frequency of KLS cells (n = 5). (B) The frequency of KLS CD41− CD48− CD150+ (KLS SLAM) cells (n = 5). (C) Competitive repopulation assays were performed, and the number of repopulating units was calculated up to 7.5 months after transplantation. Data are representative of 2 independent transplants with n = 4 or 5 mice per group per experiment. (D) Competitive repopulation assays were repeated with N-cadherin–deleted or control cells, and then secondary transplantation was performed after 12 weeks. Shown is the percentage of donor cells in the primary recipients (at 12 weeks) or secondary recipients (at 8 weeks, n = 5). (E-F) Bone marrow cells expressing the Ly5.1 locus were transplanted into irradiated N-cadherin–deleted or control mice. Donor engraftment (E) and lineage distribution (F) in the peripheral blood 38 weeks after transplantation (n = 4). Data are the mean ± SEM.

Hematopoietic engraftment is not affected by the loss of osteoblast N-cadherin

SNO cells have been reported to proliferate after total body irradiation and transplanted cells home to them.26 To determine whether N-cadherin expression contributed to engraftment, we transplanted WT bone marrow cells expressing the Ly5.1 locus into lethally irradiated Cdh2flox/flox Osx-Cre mice or control mice. All mice survived the transplant and had equal levels of multilineage engraftment at 38 weeks (Figure 3E). In addition, there was no difference in the distribution of donor-derived B-cells, T cells, or granulocytes in the peripheral blood of the recipient mice (Figure 3F). Together, these data suggest that N-cadherin expression in osteolineage cells is not required for the efficient engraftment or maintenance of hematopoietic progenitors.

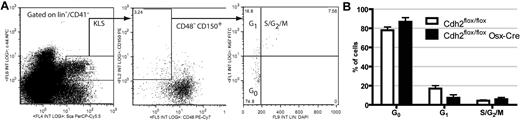

Osteoblast N-cadherin is not required to maintain HSC quiescence

HSCs expressing intermediate levels of N-cadherin have been suggested to have different cell cycle dynamics than those lacking N-cadherin,9 presumably because of increased adhesion to SNO cells. Thus, we assessed the cell cycle status of KLS SLAM cells (Figure 4A). Consistent with previous reports, the majority of KLS SLAM cells were quiescent (ie, in the G0 phase of cell cycle; Figure 4B), and loss of osteoblast N-cadherin had no significant effect on the cell cycle status of KLS SLAM cells. These data show that N-cadherin expression in osteolineage cells is not required to maintain HSC quiescence.

HSC cell cycling is normal in N-cadherin–deleted mice. (A) Representative dot plots for cell cycle analysis of KLS SLAM cells using DAPI and Ki67 staining. The gating strategy used to identify KLS SLAM cells is shown. (B) HSC cell cycle status (n = 5). Data are the mean ± SEM.

HSC cell cycling is normal in N-cadherin–deleted mice. (A) Representative dot plots for cell cycle analysis of KLS SLAM cells using DAPI and Ki67 staining. The gating strategy used to identify KLS SLAM cells is shown. (B) HSC cell cycle status (n = 5). Data are the mean ± SEM.

Deletion of osteoblast N-cadherin does not alter G-CSF mobilization

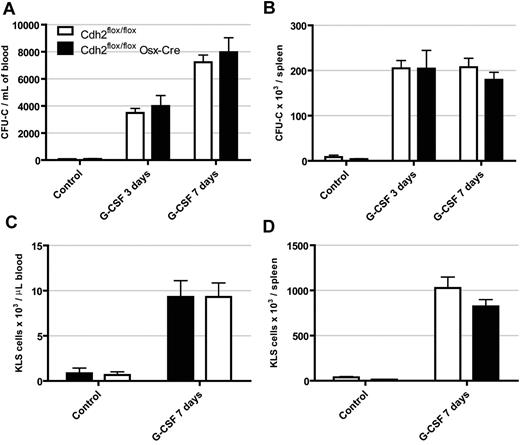

N-cadherin expression has been suggested to define a population of reserved HSCs that are activated and mobilized in response to stress.8 G-CSF is a stress cytokine commonly used clinically to mobilize HSCs from the bone marrow into the peripheral blood. Moreover, G-CSF leads to suppression of osteoblast number and function.27,28 We thus hypothesized that deletion of N-cadherin from osteoblasts may alter cellular responses to G-CSF. If N-cadherin were involved in tethering HSCs to the niche, then it would be expected that loss of N-cadherin would result in constitutive mobilization. However, at baseline, both Cdh2flox/flox Osx-Cre mice and controls had very low levels of circulating progenitors and KLS cells (Figure 5). Moreover, after 3 days or 7 days of G-CSF treatment, both cohorts of mice exhibited a similar magnitude of progenitor and KLS cell mobilization to the blood and spleen. These data show that loss of N-cadherin in osteoblasts does not affect G-CSF induced mobilization.

G-CSF induced hematopoietic progenitor mobilization is normal in N-cadherin–deleted mice. Mice were treated with G-CSF (250 μg/kg per day) for 3 or 7 days, and the number of CFU-C (A,C) and KLS cells (B,D) in the blood and spleen were determined. Data are the mean ± SEM of 4 to 11 mice.

G-CSF induced hematopoietic progenitor mobilization is normal in N-cadherin–deleted mice. Mice were treated with G-CSF (250 μg/kg per day) for 3 or 7 days, and the number of CFU-C (A,C) and KLS cells (B,D) in the blood and spleen were determined. Data are the mean ± SEM of 4 to 11 mice.

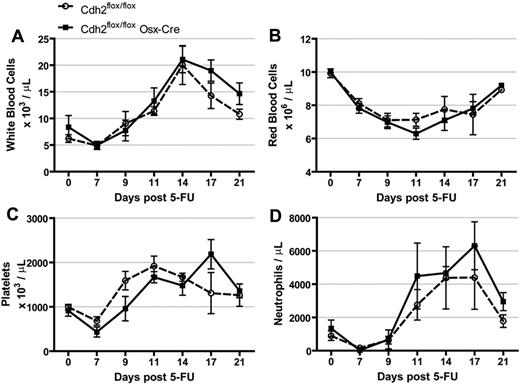

Deletion of osteoblast N-cadherin does not alter response to 5-FU

The myelosuppressive drug 5-FU kills cells cycling in the bone marrow while sparing quiescent cells, such as HSCs.29 After treatment with 5-FU, the remaining HSCs proliferate rapidly to restore blood homeostasis. N-cadherin mRNA has been reported to be up-regulated in HSCs during this proliferative period, and those HSCs that express low levels of N-cadherin are preferentially mobilized from the bone marrow.8 To determine whether deletion of osteolineage N-cadherin affects this response (a myelosuppressive stress), we treated mice with 5-FU and followed their recovery. The magnitude of myelosuppression and kinetics of hematopoietic recovery was similar in N-cadherin–deleted and control mice (Figure 6).

Response to 5-FU is normal in N-cadherin–deleted mice. Mice were treated with 150 mg/kg of 5-FU and (A) white blood cell count, (B) red blood cell count, (C) platelet count, and (D) average neutrophil count were followed over 21 days. Data are the mean ± SEM 4 to 8 mice.

Response to 5-FU is normal in N-cadherin–deleted mice. Mice were treated with 150 mg/kg of 5-FU and (A) white blood cell count, (B) red blood cell count, (C) platelet count, and (D) average neutrophil count were followed over 21 days. Data are the mean ± SEM 4 to 8 mice.

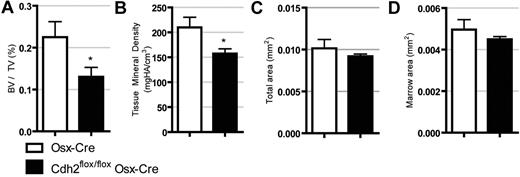

Deletion of osteoblast N-cadherin results in osteopenia

Previous studies using transgenic mice in which N-cadherin was deleted in mature osteoblasts using the Col2.3-Cre demonstrated that loss of N-cadherin leads to decreased bone mass with aging.30 Similarly, expression of a dominant negative N-cadherin in mature osteoblasts results in decreased mineralization and a shift toward adipogenesis.31 Given that osteoblast function has been linked to HSC number,1,3 we next asked whether N-cadherin deletion using the more broadly expressed Osx-Cre affects the skeletal structure. As shown in Figure 7, micro-CT analysis on 8-week-old male mice demonstrate that N-cadherin–deleted mice have significantly reduced bone volume/tissue volume and tissue mineral density, whereas total cortical area and marrow area are unchanged. These data confirm previous reports that loss of osteolineage N-cadherin results in osteopenia.

N-cadherin–deleted mice are osteopenic. MicroCT data demonstrating (A) bone volume/tissue volume, (B) tissue mineral density, (C) total cortical area, and (D) total cortical marrow area. Data are the mean ± SEM of 5 to 7 mice. *P < .05.

N-cadherin–deleted mice are osteopenic. MicroCT data demonstrating (A) bone volume/tissue volume, (B) tissue mineral density, (C) total cortical area, and (D) total cortical marrow area. Data are the mean ± SEM of 5 to 7 mice. *P < .05.

Discussion

N-cadherin was originally defined as an HSC niche molecule because long-term BrdU retaining cells (presumed to be HSCs) were preferentially localized next to SNO cells.3 Subsequent studies showed that, after transplantation of purified HSCs, approximately 60% of cells homed to SNO cells.6 These observations led to the hypothesis that N-cadherin on osteoblasts tethers HSCs to the niche and keeps them quiescent through modulation of β-catenin signaling.

Numerous groups have explored whether N-cadherin on HSCs affects their regulation, and these studies have produced conflicting results.3,8,10,11,32,33 Initial studies using the monoclonal MNCD2 anti–N-cadherin antibody suggested that N-cadherin-expressing HSCs identified a population of “reserved” HSCs that are activated under stress.8 However, other studies have raised concern about the specificity of the MNCD2 antibody,9,34 and a study using different antibodies report that N-cadherin+ cells have no repopulating activity.9 Most recently, Hosokawa et al provided convincing evidence of N-cadherin mRNA expression in phenotypic HSCs.11 On one hand, genetic ablation of Cdh2 in hematopoietic cells had no discernible effect on basal hematopoiesis, HSC number, or repopulating activity.9 On the other hand, transduction of HSCs with dominant-negative N-cadherin or knockdown of N-cadherin was associated with increased cell cycling and reduced hematopoietic engraftment.10,11 How to reconcile these divergent phenotypes is not clear; however, it has been suggested that compensatory mechanisms or redundant pathways (eg, other cadherins) might account for the lack of phenotype in HSCs genetically lacking N-cadherin.

In this study, we show that the Osx-Cre transgene efficiently deletes Cdh2 from osteolineage cells in the bone marrow, including SNO cells. N-cadherin mRNA expression in the bone marrow is reduced 20-fold, and immunostaining for N-cadherin shows a complete loss of N-cadherin protein in vitro as well in vivo. Our data show that N-cadherin expression on SNO cells (and other osteoblast-lineage cells) is dispensable for HSC maintenance. Specifically, HSC number, cell cycle status, long-term repopulating activity, and self-renewal capacity were normal. Moreover, hematopoietic engraftment into these mice and G-CSF induced HPSC mobilization are normal, suggesting that N-cadherin expression on osteolineage cells is not required for efficient engraftment or retention of HSCs in the bone marrow.

Previous studies have shown that loss of Cdh2 in mature osteoblasts using the Col2.3-Cre is associated with decreased bone mineral density.30,31 Using the earlier expressed Osx-Cre, we confirm this observation and demonstrate a more striking loss of bone density. These data thus provide another example of decoupling of bone cell function from maintenance of HSCs.9,35

Together with the study of Cdh2 deletion in HSCs by Kiel et al,9 our data strongly suggest that N-cadherin does not play a significant role in HSC maintenance or trafficking. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that other cadherins can compensate for N-cadherin's loss; for example, R-cadherin in stromal cells could theoretically form heterophilic junctions with N-cadherin on hematopoietic cells.15 In addition, the Osx-Cre deletes during embryonic development; thus, early loss of N-cadherin may be compensated by other cadherins in later life. Future studies should strive for postnatal conditional deletion of the gene to exclude this possibility. It is also important to note that these results neither argue for or against the importance of osteoblasts in regulating HSCs, nor do these results discount the role that SNO cells may play in the regulation of HSCs. SNO cells are suggested to be immature osteoblasts, and N-cadherin may simply mark an earlier developmental stage of osteoblasts important for niche maintenance. Several different types of stromal cells have been described to support HSCs, including sinusoidal endothelial cells,36 osteoprogenitors,37 and mesenchymal stem cells.38 It is possible that N-cadherin expression is these stromal cell types may contribute to HSC maintenance. Studies that delete N-cadherin from these other stormal cell populations are required to address this possibility.

There is an Inside Blood commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Valerie Salazar for technical assistance and advice regarding osteoblast function; Alex Khalaf and Dr Fulu Liu for technical assistance; Gayle Callis and Dr Andrea Hooper for advice on immunofluorescence; and Jackie Tucker-Davis for animal care.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants F30 HL097423-01, A.M.G.; R01 AR055913, R.C.; and R01 HL60772, D.C.L.).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: A.M.G. designed and performed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; L.D.R. performed the in vitro culture and assisted with the micro-CT; J.R.W. assisted in the 5-FU and G-CSF experiments; and R.C. and D.C.L. supervised all of the research and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Daniel C. Link, Division of Oncology, Washington University School of Medicine, Campus Box 8007, 660 S Euclid Ave, St Louis, MO 63110; e-mail: dlink@dom.wustl.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal