Abstract

The periprocedural management of patients receiving long-term oral anticoagulant therapy remains a common but difficult clinical problem, with a lack of high-quality evidence to inform best practices. It is a patient's thromboembolic risk that drives the need for an aggressive periprocedural strategy, including the use of heparin bridging therapy, to minimize time off anticoagulant therapy, while the procedural bleed risk determines how and when postprocedural anticoagulant therapy should be resumed. Warfarin should be continued in patients undergoing selected minor procedures, whereas in major procedures that necessitate warfarin interruption, heparin bridging therapy should be considered in patients at high thromboembolic risk and in a minority of patients at moderate risk. Periprocedural data with the novel oral anticoagulants, such as dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban, are emerging, but their relatively short half-life, rapid onset of action, and predictable pharmacokinetics should simplify periprocedural use. This review aims to provide a practical, clinician-focused approach to periprocedural anticoagulant management.

Introduction

The periprocedural management of patients who are receiving long-term oral anticoagulant therapy, usually with a vitamin K antagonist (VKA), such as warfarin, is a common but complex clinical problem, affecting an estimated 250 000 patients per year in North America alone or approximately 1 in 10 patients on chronic VKA.1 It is well established that continuing oral anticoagulation is associated with an increased risk of bleeding in the periprocedural period and that the absence of anticoagulant therapy postoperatively confers a marked increased risk for venous thromboembolism (VTE), especially after major surgery.2,3 Emerging data suggest that interruption of warfarin in patients with arterial indications, especially in the immediate postoperative period, confers a higher risk of arterial thromboembolism (ATE) than predicted by mathematical modeling assumptions.4,5 The accumulating clinical data relating to periprocedural antithrombotic therapy has necessitated the development of new chapters and recommendations in clinical practice guidelines that are dedicated to periprocedural antithrombotic management.1,6,7

It has been suggested that the use of periprocedural bridging anticoagulation with parenteral heparin, either unfractionated heparin (UFH), or low molecular weight heparin (LMWH), would mitigate the risk of periprocedural thromboembolism by allowing for continued anticoagulation during temporary discontinuation of VKAs for an elective procedure or surgery.8 Since 2003, there have been multiple observational cohort studies of heparin bridging therapy with well-described periprocedural bridging protocols and well-defined and objectively verified outcomes.9 However, the quality of evidence with which to inform best practices is weak, with no randomized trials, few control groups, and no placebo arms to assess the safety and efficacy of bridging therapy. Although in the past decade we have learned “how to bridge” in perceived at-risk patients on warfarin needing temporary interruption for an elective procedure or surgery, the more crucial question of “should I bridge” remains unanswered.

The emergence and anticipated routine clinical use of novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs), such as the direct factor IIa (thrombin) inhibitor dabigatran and the direct factor Xa inhibitors rivaroxaban and apixaban, have the potential to greatly simplify periprocedural anticoagulant management because of their relatively short elimination half-lives, rapid onset of action, predictable pharmacokinetic properties, and few drug-drug interactions.10 There is emerging guidance for NOAC-treated patients who may require anticoagulant reversal and measurement of hemostatic function.10,11 Although periprocedural protocols for the use of the NOACs in the absence of robust clinical data are emerging,12,13 early reports as to their use and clinical outcomes in the immediate periprocedural period using large databases from phase 3 clinical trials will be forthcoming in constructing evidence-based periprocedural guideline recommendations.14

This review will use a case-based approach to illustrate the periprocedural management of patients on chronic oral anticoagulant therapy in clinical practice. Our aims are to address: (1) patients on VKA undergoing minor procedures; (2) patients on VKA needing temporary anticoagulant interruption for an elective surgery or procedure; (3) the use of heparin bridging therapy; and (4) the periprocedural management of patients receiving a NOAC. Our clinical guidance discussed herein will incorporate the best available evidence, acknowledging that this evidence can be weak or based solely on expert opinion.

Thrombotic risk when discontinuing oral anticoagulant therapy in the periprocedural period

In patients with VTE indications for VKA therapy, it is estimated that the risk of recurrence is 40% in the first month after discontinuing a VKA and 10% during the subsequent 2 months.2 The overall risk of recurrence is much lower after 3 months of VKA therapy, estimated at 15% for the first year.2 Acquired hypercoagulable states, such as the antiphospholipid syndrome, active malignancy and certain congenital thrombophilias (eg, homozygous factor V Leiden), are independent risk factors for VTE recurrence.15,16

In patients with arterial indications for VKA therapy, patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) or mechanical heart valves (MHV) are at increased risk of stroke in the absence of warfarin therapy or with subtherapeutic levels of anticoagulation.5,17 For patients with NVAF, the CHADS2 score is a validated clinical prediction score that uses congestive heart failure, hypertension, age > 75 years, diabetes, and history of stroke or transient ischemic attack in a cumulative manner to estimate expected stroke rate per 100-patient years in nonsurgical settings.18 Recently, preliminary data suggest that the CHADS2 score may also be used to predict risk for postsurgical stroke.19 Thus, patients with CHADS2 scores of 5 or 6 would be considered at high risk of thrombosis.

Patients with MHVs are at increased risk of systemic embolization and occlusive thrombus of the orifice of the prosthetic valve during subtherapeutic levels of warfarin, especially when the international normalized ratio (INR) falls below 2.0.20 Older, caged-ball valves (ie, Starr-Edwards) are the most thrombogenic, followed by tilting disc valves (ie, Bjork-Shiley), and with bileaflet valves (ie, St Jude) being the least thrombogenic.21 In the absence of anticoagulant therapy, mitral position valves have an annualized risk of thrombosis of 22% compared with aortic position valves, with an annualized risk of approximately 10%-12%,21 Similarly, patients with caged-ball valves, mitral position valves, and prosthetic valves with other risk factors for embolization (such as prior embolic event, severe left ventricular dysfunction, and an underlying hypercoagulable state) are considered at high risk for thrombosis.22

The American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP), as part of their most recent 9th Edition Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines on Antithrombotic Therapy, suggest a clinically useful thromboembolic risk stratification in the periprocedural period as shown in Table 1.7 The 3 most common groups of patients receiving VKAs (those with VTE, MHV, and NVAF indications) are divided into a 3-tier low-, intermediate-, and high-risk scheme for periprocedural thromboembolic risk. It is a patient's thromboembolic risk that should drive the need for a conservative or aggressive strategy (such as bridging therapy) with respect to periprocedural antithrombotic management.

Suggested risk stratification for perioperative thromboembolism7

| Risk category . | MHV . | Atrial fibrillation . | VTE . |

|---|---|---|---|

| High (> 10%/y risk of ATE or > 10%/mo risk of VTE) | Any mechanical mitral valve | CHADS2 score of 5 or 6 | Recent (< 3 mo) VTE |

| Caged-ball or tilting disc valve in mitral/aortic position | Recent (< 3 mo) stroke or TIA | Severe thrombophilia | |

| Deficiency of protein C, protein S or antithrombin | |||

| Recent (< 6 mo) stroke or TIA | Rheumatic valvular heart disease | Antiphospholipid antibodies | |

| Multiple thrombophilias | |||

| Intermediate (4%-10%/y risk of ATE or 4%-10%/mo risk of VTE) | Bileaflet AVR with major risk factors for stroke | CHADS2 score of 3 or 4 | VTE within past 3-12 mo |

| Recurrent VTE | |||

| Nonsevere thrombophilia | |||

| Active cancer | |||

| Low (< 4%/y risk of ATE or < 2%/mo risk of VTE) | Bileaflet AVR without major risk factors for stroke | CHADS2 score of 0-2 (and no prior stroke or TIA) | VTE > 12 mo ago |

| Risk category . | MHV . | Atrial fibrillation . | VTE . |

|---|---|---|---|

| High (> 10%/y risk of ATE or > 10%/mo risk of VTE) | Any mechanical mitral valve | CHADS2 score of 5 or 6 | Recent (< 3 mo) VTE |

| Caged-ball or tilting disc valve in mitral/aortic position | Recent (< 3 mo) stroke or TIA | Severe thrombophilia | |

| Deficiency of protein C, protein S or antithrombin | |||

| Recent (< 6 mo) stroke or TIA | Rheumatic valvular heart disease | Antiphospholipid antibodies | |

| Multiple thrombophilias | |||

| Intermediate (4%-10%/y risk of ATE or 4%-10%/mo risk of VTE) | Bileaflet AVR with major risk factors for stroke | CHADS2 score of 3 or 4 | VTE within past 3-12 mo |

| Recurrent VTE | |||

| Nonsevere thrombophilia | |||

| Active cancer | |||

| Low (< 4%/y risk of ATE or < 2%/mo risk of VTE) | Bileaflet AVR without major risk factors for stroke | CHADS2 score of 0-2 (and no prior stroke or TIA) | VTE > 12 mo ago |

TIA indicates transient ischemic attack; AVR, aortic valve replacement; ATE, arterial thromboembolism; VTE, venous thromboembolism; and MHV, mechanical heart valve.

Lastly, in addition to patient-related factors for thrombosis, there is a well-described prothrombotic effect of major surgery and laparoscopic procedures where the presence of pneumoperitoneum and reverse Trendelenburg position may introduce additional thrombotic risk.23 Although it is estimated that surgery will theoretically increase the postoperative VTE risk 100-fold,2,23,24 there is emerging evidence that surgery may also increase the risk of ATE in the postoperative period, with recent estimates suggesting a 10-fold higher than expected risk of stroke in the periprocedural period in warfarin-treated patients compared with mathematical modeling assumptions.4,25

Bleed risk in the periprocedural period

A patient's previous history of bleeding, especially with invasive procedures or trauma, is an important determinant in assessing surgical bleeding risk, as is use of concomitant antiplatelet and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications. As shown in Table 2, surgical procedures that appear to have a high bleeding risk include major cardiovascular surgery, orthopedic surgery, head and neck cancer surgery, urologic surgery, and surgeries and procedures lasting ≥ 45 minutes. Procedures with a low bleeding risk include nonmajor procedures (lasting < 45 minutes), such as general surgical procedures, cutaneous procedures, and cholecystectomy.26 Procedural bleeding risks have also been identified as high risk or low risk by various surgical and subspecialty societies.27,28 A reasonable estimate of perioperative major bleeding with the use of periprocedural anticoagulants is 2%-4% for major surgery and 0%-2% for nonmajor surgery or minor procedures.29

| High (2-day risk of major bleed 2%-4%) |

| Heart valve replacement |

| Coronary artery bypass |

| Abdominal aortic aneurysm repair |

| Neurosurgical/urologic/head and neck/abdominal/breast cancer surgery |

| Bilateral knee replacement |

| Laminectomy |

| Transurethral prostate resection |

| Kidney biopsy |

| Polypectomy, variceal treatment, biliary sphincterectomy, pneumatic dilatation |

| PEG placement |

| Endoscopically guided fine-needle aspiration |

| Multiple tooth extractions |

| Vascular and general surgery |

| Any major operation (procedure duration > 45 minutes) |

| Low (2-day risk of major bleed 0%-2%) |

| Cholecystectomy |

| Abdominal hysterectomy |

| Gastrointestinal endoscopy ± biopsy, enteroscopy, biliary/pancreatic stent without sphincterotomy, endonosonography without fine-needle aspiration |

| Pacemaker and cardiac defribillator insertion and electrophysiologic testing |

| Simple dental extractions |

| Carpal tunnel repair |

| Knee/hip replacement and shoulder/foot/hand surgery and arthroscopy |

| Dilatation and curettage |

| Skin cancer excision |

| Abdominal hernia repair |

| Hemorrhoidal surgery |

| Axillary node dissection |

| Hydrocele repair |

| Cataract and noncataract eye surgery |

| Noncoronary angiography |

| Bronchoscopy ± biopsy |

| Central venous catheter removal |

| Cutaneous and bladder/prostate/thyroid/breast/lymph node biopsies |

| High (2-day risk of major bleed 2%-4%) |

| Heart valve replacement |

| Coronary artery bypass |

| Abdominal aortic aneurysm repair |

| Neurosurgical/urologic/head and neck/abdominal/breast cancer surgery |

| Bilateral knee replacement |

| Laminectomy |

| Transurethral prostate resection |

| Kidney biopsy |

| Polypectomy, variceal treatment, biliary sphincterectomy, pneumatic dilatation |

| PEG placement |

| Endoscopically guided fine-needle aspiration |

| Multiple tooth extractions |

| Vascular and general surgery |

| Any major operation (procedure duration > 45 minutes) |

| Low (2-day risk of major bleed 0%-2%) |

| Cholecystectomy |

| Abdominal hysterectomy |

| Gastrointestinal endoscopy ± biopsy, enteroscopy, biliary/pancreatic stent without sphincterotomy, endonosonography without fine-needle aspiration |

| Pacemaker and cardiac defribillator insertion and electrophysiologic testing |

| Simple dental extractions |

| Carpal tunnel repair |

| Knee/hip replacement and shoulder/foot/hand surgery and arthroscopy |

| Dilatation and curettage |

| Skin cancer excision |

| Abdominal hernia repair |

| Hemorrhoidal surgery |

| Axillary node dissection |

| Hydrocele repair |

| Cataract and noncataract eye surgery |

| Noncoronary angiography |

| Bronchoscopy ± biopsy |

| Central venous catheter removal |

| Cutaneous and bladder/prostate/thyroid/breast/lymph node biopsies |

This table is based on definitions derived from surgical/subspecialty societies in anticoagulant bridging or anticoagulant bridging management studies.

Overall periprocedural antithrombotic strategy

Patient-related and procedure-related risk factors for both thrombosis and bleeding for a patient on chronic oral anticoagulant therapy undergoing a specific surgery or procedure should be considered when developing a periprocedural antithrombotic strategy. Although the thromboembolic risk categories previously defined as high, intermediate, and low have not been prospectively validated and may have some overlap, there is considerable usefulness in their designation in developing a periprocedural antithrombotic strategy. The clinical consequences of a thrombotic or bleeding event must be taken into consideration: MHV thrombosis is fatal in 15% of patients, embolic stroke results in death or major disability in 70% of patients, while VTE has a case-fatality rate of approximately 5%-9%, and major bleeding has a case-fatality rate of ∼ 8%-10%.30-34

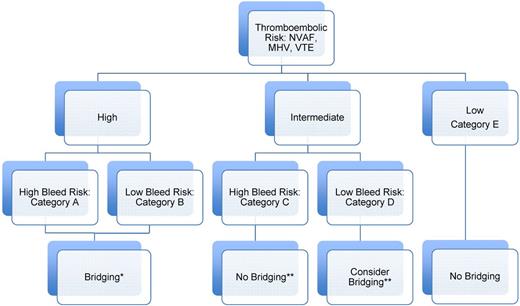

An overall periprocedural antithrombotic strategy for a patient on chronic oral anticoagulation should be conceptualized in the scheme shown in Figure 1 within 5 categories (A-E) based on a 3-tier thromboembolic risk scheme and a 2-tier bleed risk scheme. It is a patients' estimated thromboembolic risk that determines whether a conservative or aggressive periprocedural antithrombotic strategy is used (such as bridging therapy). It is the procedural bleed risk that determines how that strategy is used in the postoperative period (such as stepwise increase in anticoagulant intensity). Lastly, because of the more severe clinical consequences with ATE than major bleeding, a strategy that incurs 3-10 more major bleeds to prevent one stroke would be, in theory, clinically acceptable based on the trade-off between the clinical consequences of a stroke as compared with a bleed.

Suggested periprocedural heparin bridging strategies for patients on chronic VKA based on patient thromboembolic and procedural bleed risk. Data from the 9th edition ACCP Guidelines: all grade 2C, except intermediate TE risk.7 *For high-bleed risk procedures: wait a full 48-72 hours before reinitiating postprocedural heparin (LMWH) bridging (especially treatment dose); stepwise increase in postprocedural heparin (LMWH) dose from prophylactic dose first 24-48 hours to intermediate/treatment dose; no postprocedural heparin (LMWH) bridging in very high bleed risk procedures (ie, major neurosurgical or cardiovascular surgeries) but use of mechanical prophylaxis. **Based on individual patient- and procedural-related risk factors for thrombosis and bleeding.

Suggested periprocedural heparin bridging strategies for patients on chronic VKA based on patient thromboembolic and procedural bleed risk. Data from the 9th edition ACCP Guidelines: all grade 2C, except intermediate TE risk.7 *For high-bleed risk procedures: wait a full 48-72 hours before reinitiating postprocedural heparin (LMWH) bridging (especially treatment dose); stepwise increase in postprocedural heparin (LMWH) dose from prophylactic dose first 24-48 hours to intermediate/treatment dose; no postprocedural heparin (LMWH) bridging in very high bleed risk procedures (ie, major neurosurgical or cardiovascular surgeries) but use of mechanical prophylaxis. **Based on individual patient- and procedural-related risk factors for thrombosis and bleeding.

Management of patients on chronic oral anticoagulant therapy undergoing minor procedures

Case 1

A 48-year-old woman on chronic warfarin with a Starr-Edwards prosthetic heart valve in the mitral position is having multiple dental extractions requiring local anesthetic injections.

This patient is at high thromboembolic risk (older generation prosthetic heart valve in the mitral position) and is undergoing a minor procedure (multiple dental extractions). Approximately 15%-20% of patients receiving a VKA who are assessed for perioperative anticoagulant management require minor dental, dermatologic, or ophthalmologic procedures.26 The majority of these procedures are associated with little or self-limiting blood loss that can be controlled with local hemostatic measures.

Minor dental procedures include tooth extractions, endodontic (root canal), and minor reconstructive procedures. Clinical data (which includes randomized trials with limitations) support 2 approaches: (1) continuation of VKA and the use of a prohemostatic agent (such as oral tranexamic acid mouthwash with local application and expectoration), or (2) partial interruption of VKA therapy 2-3 days before the procedure.35,36 Both approaches are associated with a low risk of clinically relevant bleeding (< 5%) and rare thromboembolic outcomes (< 0.1%), although minor bleeding (such as oozing from gingival mucosa) may be common.

For patients undergoing minor dermatologic procedures (including excision of skin cancers), cohort studies indicate a low incidence of major bleeding (< 5%) in patients who continued VKA therapy.37 There was a 3-fold higher incidence of nonmajor and minor bleeding with this approach, although most of these episodes were self-limiting. For ophthalmologic procedures, which include mostly cataract surgery, a meta-analysis of observational studies found an increased risk for bleeding (odds ratio [OR] = 3.26; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.73-6.16) in patients who continued VKA, but almost all bleeds were self-limiting, consisting of dot hyphemas or subconjunctival bleeds without compromised visual acuity.38 Retrobulbar hematoma in such patients who continued VKAs while undergoing retrobulbar anesthesia was also rare.

Management of patients on chronic oral anticoagulant therapy requiring temporary interruption for major procedures

Case 2

A 51-year-old woman on chronic warfarin (target INR 2.5) with an aortic-position St Jude valve is having a colonoscopy to investigate rectal bleeding. She does not have a history of stroke, transient-ischemic attack, hypertension, diabetes, or systolic heart dysfunction. The gastroenterologist believes that this colonoscopy is diagnostic only, but it would depend on whether a lesion is amenable to therapy.

This patient with an aortic-position St Jude MHV without other stroke risk factors is at low thromboembolic risk and will undergo a low-bleed risk procedure with a diagnostic colonoscopy. She would fall into category E by our risk scheme. Bridging therapy would not be recommended. The timing of interruption of VKA therapy must be carefully considered based on the anticipated length of time required for sufficient lowering of a patient's INR. The ACCP Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines recommend discontinuing warfarin 5 days before a procedure to allow for INR lowering.1 In patients with an INR between 2.0 and 3.0, the INR has been shown to decrease to < 1.5 within 115 hours after withholding warfarin.39 Thus, for a patient with an INR between 2.0 and 3.0, a washout period withholding 5 warfarin doses could be used to reduce the INR to < 1.5 before surgery. For elderly patients, patients with a high-intensity INR range (INR 3.0-4.0), or patients receiving longer-lasting coumarins, such as phenprocoumon, a longer period of interruption is recommended to reach the preferred preoperative INR range.39,40 Before surgery, an INR of ≤ 1.5 is recommended.11,41 In many cases, the variability in decreasing INR over time warrants INR testing on the day before surgery. If it is elevated (usually > 1.8), there are data to suggest that the patient would benefit by receiving low-dose oral vitamin K (1-2.5 mg) for reversal.42 If the INR < 1.5, then one can proceed with the intervention. Once adequate hemostasis is achieved, our practice is to resume warfarin postoperatively at the usual maintenance dose (or some clinicians would give twice the maintenance dose) the same evening or the next morning with continued monitoring.43

Case 3

An obese 48-year-old woman with antiphospholipid syndrome and recurrent venous thrombosis (including recurrent pulmonary embolism) on chronic high intensity warfarin (INR range, 2.3-3.5) is being considered for a spinal laminectomy. She will be receiving neuraxial anesthesia.

This represents a challenging case of a patient at high thromboembolic risk (antiphospholipid syndrome with recurrent thrombosis) undergoing a procedure with potential catastrophic consequences for bleeding. She would fall into category A. The patient's preprocedural and postprocedural warfarin management should follow a similar strategy as our previous patient (it is of greater importance that a day −1 INR is drawn in this setting to make sure it is < 1.5). In this setting, the 9th edition ACCP Guidelines would suggest the use of heparin bridging therapy, especially as heparin will reduce the postoperative VTE risk by approximately two-thirds.2,7 This must be tempered by data indicating that a major bleed rate as high as ∼ 20% may be expected if treatment-dose LMWH is given as postprocedural bridging too close to the time of surgery and without regard for surgical bleed risk.44

Periprocedural bridging therapy should be initiated in the outpatient setting, when feasible, using bridging regimens (specifically LMWH) and a validated protocol, as shown in Table 3. Bridging therapy using LMWH injections should start ∼ 36 hours after the last warfarin dose, usually around 3 days before surgery. The last dose of LMWH is administered 24 hours before the procedure using half the normal daily dose because discontinuing LMWH therapy too close to the time of surgery may increase the risk of bleeding because of a residual anticoagulant effect.45 Within 24 hours after a minor procedure, it is recommended that LMWH be resumed at the patient's full daily therapeutic dose.1,46 Recently, bridging regimens using intermediate doses of LMWH have also shown favorable safety and efficacy profiles.47,48 If a procedure is major or confers a high risk of bleeding (such as our patient undergoing spinal laminectomy), options include waiting 48-72 hours after surgery before resuming full-dose LMWH bridging therapy, using an intermediate or prophylactic LMWH dose, or, if the procedural bleeding risk is extremely high, foregoing bridging therapy altogether and using mechanical methods of thromboprophylaxis, such as pneumatic compression devices.1,6 Lastly, when neuraxial anesthesia is considered, the dosing of LMWH should conform to evidence-based guidelines from the American Society of Regional Anesthesia: waiting a full 24 hours after the last treatment-dose LMWH is administered before a spinal/epidural catheter is placed, and delaying LMWH 2 hours after catheter removal.49

Periprocedural anticoagulation and bridging protocol

| Day . | Intervention . |

|---|---|

| Preprocedural intervention | |

| −7 to −10 | Assess for perioperative bridging anticoagulation; classify patients as undergoing high-bleeding risk or low-bleeding risk procedure; check baseline labs (Hgb, platelet count, creatinine, INR) |

| −7 | Stop aspirin (or other antiplatelet drugs) |

| −5 or −6 | Stop warfarin |

| −3 | Start LMWH at therapeutic or intermediate dose* |

| −1 | Last preprocedural dose of LMWH administered no less than 24 h before start of surgery at half the total daily dose; assess INR before the procedure; proceed with surgery if INR < 1.5; if INR > 1.5 and < 1.8, consider low-dose oral vitamin K reversal (1-2.5 mg) |

| Day of procedural intervention | |

| 0 or +1 | Resume maintenance dose of warfarin on evening of or morning after procedure† |

| Postprocedural intervention | |

| +1 | Low-bleeding risk: restart LMWH at previous dose; resume warfarin therapy |

| High-bleeding risk: no LMWH administration; resume warfarin therapy | |

| +2 or +3 | Low-bleeding risk: LMWH administration continued |

| High-bleeding risk: restart LMWH at previous dose | |

| +4 | Low-bleeding risk: INR testing (discontinue LMWH if INR > 1.9) |

| High-bleeding risk: INR testing (discontinue LMWH if INR > 1.9) | |

| +7 to +10 | Low-bleeding risk: INR testing |

| High bleeding risk: INR testing |

| Day . | Intervention . |

|---|---|

| Preprocedural intervention | |

| −7 to −10 | Assess for perioperative bridging anticoagulation; classify patients as undergoing high-bleeding risk or low-bleeding risk procedure; check baseline labs (Hgb, platelet count, creatinine, INR) |

| −7 | Stop aspirin (or other antiplatelet drugs) |

| −5 or −6 | Stop warfarin |

| −3 | Start LMWH at therapeutic or intermediate dose* |

| −1 | Last preprocedural dose of LMWH administered no less than 24 h before start of surgery at half the total daily dose; assess INR before the procedure; proceed with surgery if INR < 1.5; if INR > 1.5 and < 1.8, consider low-dose oral vitamin K reversal (1-2.5 mg) |

| Day of procedural intervention | |

| 0 or +1 | Resume maintenance dose of warfarin on evening of or morning after procedure† |

| Postprocedural intervention | |

| +1 | Low-bleeding risk: restart LMWH at previous dose; resume warfarin therapy |

| High-bleeding risk: no LMWH administration; resume warfarin therapy | |

| +2 or +3 | Low-bleeding risk: LMWH administration continued |

| High-bleeding risk: restart LMWH at previous dose | |

| +4 | Low-bleeding risk: INR testing (discontinue LMWH if INR > 1.9) |

| High-bleeding risk: INR testing (discontinue LMWH if INR > 1.9) | |

| +7 to +10 | Low-bleeding risk: INR testing |

| High bleeding risk: INR testing |

LMWH regimens include enoxaparin 1.5 mg/kg once daily or 1.0 mg/kg twice daily subcutaneously; dalteparin 200 IU/kg once daily or 100 IU/kg twice daily subcutaneously; and tinzaparin 175 IU/kg once daily subcutaneously. Intermediate-dose LMWH (ie, nadroparin 2850-5700 U twice daily subcutaneously; enoxaparin 40 mg twice daily subcutaneously) has been less studied in this setting

Loading doses (ie, 2 times the daily maintenance dose) of warfarin have also been used.

A recent systematic review of 7169 patients undergoing periprocedural bridging therapy found a 0.9% rate of thromboembolism (95% CI, 0.0%-3.4%) coupled with a rate of major bleeding of 4.3% (95% CI, 2.4%-6.2%) when mostly treatment-dose LMWH bridging was used.50 In the absence of high-quality placebo-controlled data to inform whether we should use bridging therapy, this appears as an acceptable trade-off for our high-risk patient given the high case-fatality of thrombosis compared with major bleeding as discussed previously.

Case 4

A 78-year-old man on chronic warfarin (target INR 2.5) with a history of nonvalvular atrial fibrillation, hypertension, and adult-onset diabetes mellitus for 15 years will be undergoing a transurethral resection of the prostate for benign prostatic hyperplasia.

This case illustrates a patient at intermediate risk of thromboembolism undergoing a high-bleed risk urologic procedure, who would fall under category C in our risk scheme. His advanced age, hypertension, and history of diabetes would give him at a CHADS2 score of 3, placing him at intermediate (or moderate) thrombotic risk. The intermediate-risk group is the largest patient group on chronic VKA being evaluated in the periprocedural setting and the group with the greatest clinical equipoise as to the need for heparin bridging.9 Although it is clear that our patient would need to stop and restart warfarin around the time of his procedure using well-described protocols (and assessment of adequate hemostasis postprocedure), it is less clear that he would benefit from heparin bridging therapy. Although the 2008 ACCP Guidelines suggested the use of heparin bridging (grade 2C) for moderate thromboembolic risk patients on chronic VKA, the more methodologically stringent 2012 9th Edition ACCP Guidelines did not provide a recommendation for moderate risk groups and suggested an individualized assessment based on risk factors for thrombosis and bleeding.1,7

The previously discussed large systematic review and meta-analysis of bridging therapy found no significant risk reduction for TE (including ATE) with bridging anticoagulation (0.80; 95% CI, 0.42-1.54).50 However, the bridging treatment and comparison groups had different TE risks at baseline, with the majority of bridged patients at high risk of TE events. Two large placebo-controlled randomized trials, using treatment-dose LMWH as bridging therapy (BRIDGE and PERIOP-2), are ongoing and aim to inform clinical practice with high-quality data as to the need for periprocedural bridging anticoagulation in patients with arterial indications for warfarin, such as NVAF.51,52 It is expected that the majority of patients in these trials will fall under the intermediate thrombotic risk category, such as the case of our patient.

Management of patients on novel oral anticoagulants undergoing elective procedures or surgeries

Case 5

A 73-year-old woman with atrial fibrillation and a CHADS2 score of 4 (prior stroke, diabetes, hypertension) is receiving dabigatran, 150 mg twice a day and is scheduled for elective hip replacement with spinal anesthesia. She has moderate renal insufficiency, with an estimated creatinine clearance (CrCl) of 38 mL/min.

In patients who are receiving dabigatran and require elective surgery, the timing of preoperative dabigatran interruption to ensure a minimal or no residual anticoagulant effect at surgery is predicated on 3 factors: (1) elimination half-life of dabigatran, (2) patient renal function and its effect on dabigatran elimination, and (3) planned surgery and anesthesia.10,12 In patients with renal function that is normal (CrCl > 80 mL/min) or mildly impaired (CrCl, 50-80 mL/min) dabigatran has an elimination half-life of 14-17 hours,53 which implies that in such patients the last dabigatran dose should be given 3 days before surgery (ie, skip 4 doses). This period of interruption corresponds to 4-5 dabigatran half-lives (48-60 hours) which, in turn, corresponds to a minimal (∼ 3%-6%) anticoagulant effect at surgery. In patients with moderately impaired renal function, as in case 5, the half-life of dabigatran is 16-18 hours54 ; and to allow 4-5 half-lives (64-90 hours) to elapse between the last dabigatran dose and surgery would require the last dose to be given 5 days before surgery (ie, skip 8 doses). If this patient was having minor surgery (eg, laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair), a 2-day period of dabigatran interruption (ie, 4 doses skipped) may be reasonable, as this would allow 2-3 drug half-lives to elapse with a modest (∼ 12%-25%) residual anticoagulant effect at surgery.

There is uncertainty about when to safely stop dabigatran before surgery, we suggest the default management is to give the last dose of dabigatran 3 days before surgery (ie, skip 4 doses) in all patients with normal or mildly impaired renal function (CrCl > 50 mL/min) and to give the last dose of dabigatran 5 days before (skip 8 doses) in all patients with moderately impaired renal function (CrCl = 30-50 mL/min). Our suggested preoperative management for dabigatran-treated patients is shown in Table 4.

Preoperative interruption of new oral anticoagulants: a suggested management approach

| Drug (dose)* . | Patient renal function . | Low bleeding risk surgery† (2 or 3 drug half-lives between last dose and surgery) . | High bleeding risk surgery‡ (4 or 5 drug half-lives between last dose and surgery) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dabigatran (150 mg twice daily) | |||

| t1/2 = 14-17 h | Normal or mild impairment (CrCl > 50 mL/min) | Last dose: 2 days before surgery (skip 2 doses) | Last dose: 3 days before surgery (skip 4 doses) |

| t1/2 = 16-18 h | Moderate impairment (CrCl 30-50 mL/min) | Last dose: 3 days before surgery (skip 4 doses) | Last dose: 4-5 days before surgery (skip 6-8 doses) |

| Rivaroxaban (20 mg once daily) | |||

| t1/2 = 8-9 h | Normal or mild impairment (CrCl > 50 mL/min) | Last dose: 2 days before surgery (skip 1 dose) | Last dose: 3 days before surgery (skip 2 doses) |

| t1/2 = 9 h | moderate impairment (CrCl 30-50 mL/min) | Last dose: 2 days before surgery (skip 1 dose) | Last dose: 3 days before surgery (skip 2 doses) |

| t1/2 = 9-10 h | Severe impairment§ (CrCl 15-29.9 mL/min) | Last dose: 3 days before surgery (skip 2 doses) | Last dose: 4 days before surgery (skip 3 doses) |

| Apixaban (5 mg twice daily) | |||

| t1/2 = 7-8 h | Normal or mild impairment (CrCl > 50 mL/min) | Last dose: 2 days before surgery (skip 2 doses) | Last dose: 3 days before surgery (skip 4 doses) |

| t1/2 = 17-18 h | Moderate impairment (CrCl 30-50 mL/min) | Last dose: 3 days before surgery (skip 4 doses) | Last dose: 4 days before surgery (skip 6 doses) |

| Drug (dose)* . | Patient renal function . | Low bleeding risk surgery† (2 or 3 drug half-lives between last dose and surgery) . | High bleeding risk surgery‡ (4 or 5 drug half-lives between last dose and surgery) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dabigatran (150 mg twice daily) | |||

| t1/2 = 14-17 h | Normal or mild impairment (CrCl > 50 mL/min) | Last dose: 2 days before surgery (skip 2 doses) | Last dose: 3 days before surgery (skip 4 doses) |

| t1/2 = 16-18 h | Moderate impairment (CrCl 30-50 mL/min) | Last dose: 3 days before surgery (skip 4 doses) | Last dose: 4-5 days before surgery (skip 6-8 doses) |

| Rivaroxaban (20 mg once daily) | |||

| t1/2 = 8-9 h | Normal or mild impairment (CrCl > 50 mL/min) | Last dose: 2 days before surgery (skip 1 dose) | Last dose: 3 days before surgery (skip 2 doses) |

| t1/2 = 9 h | moderate impairment (CrCl 30-50 mL/min) | Last dose: 2 days before surgery (skip 1 dose) | Last dose: 3 days before surgery (skip 2 doses) |

| t1/2 = 9-10 h | Severe impairment§ (CrCl 15-29.9 mL/min) | Last dose: 3 days before surgery (skip 2 doses) | Last dose: 4 days before surgery (skip 3 doses) |

| Apixaban (5 mg twice daily) | |||

| t1/2 = 7-8 h | Normal or mild impairment (CrCl > 50 mL/min) | Last dose: 2 days before surgery (skip 2 doses) | Last dose: 3 days before surgery (skip 4 doses) |

| t1/2 = 17-18 h | Moderate impairment (CrCl 30-50 mL/min) | Last dose: 3 days before surgery (skip 4 doses) | Last dose: 4 days before surgery (skip 6 doses) |

Estimated t1/2 based on renal clearance.

Aiming for mild to moderate residual anticoagulant effect at surgery (< 12%-25%).

Aiming for no or minimal residual anticoagulant effect (< 3%-6%) at surgery.

Patients receiving rivaroxaban, 15 mg once daily.

In the RE-LY trial, a > 18 000-patient randomized trial comparing dabigatran (150 mg twice a day or 110 mg twice a day) with warfarin for stroke prevention in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation,55 management of dabigatran for patients who required elective surgery was left to the discretion of the treating physician. However, midway through the study, a standardized protocol was adopted for preoperative interruption of dabigatran and is similar to that suggested in Table 4. In RE-LY, there were > 4500 patients who had a first interruption of anticoagulation, in whom the last dose of dabigatran was given < 2 days, 2-5 days, and > 5 days before surgery in 37%, 33%, and 13% of patients, respectively. There was no statistically significant difference in perioperative major bleeding among dabigatran-treated patients (3.8% with 110-mg dose, 5.1% with 150-mg dose) and warfarin-treated patients (4.6%).14 Moreover, the incidence of ATE was low (< 1%), irrespective of anticoagulant therapy. Taken together, these findings suggest that dabigatran-treated patients are not at increased risk for perioperative adverse clinical consequences compared with warfarin-treated patients.

In patients having minor procedures (dental, skin, cataract) or coronary angiography, in whom warfarin can be safely continued,7 it may be reasonable also to continue dabigatran in dabigatran-treated patients undergoing these procedures. However, clinical data to support this approach are, to date, lacking.

Two practical issues relating to resuming dabigatran and other NOACs after surgery are their relatively rapid onset of action, with peak levels occurring 1-3 hours after ingestion,13 and the potential effect of postoperative bowel dysmotility and use of acid-suppressive therapy on drug absorption. The rapid peak anticoagulant effect is similar to that of LMWH; therefore, resuming a therapeutic-dose NOAC (eg, dabigatran 150 mg twice a day or rivaroxaban 20 mg once daily) after surgery may be similar to resuming a treatment-dose LMWH bridging regimen (eg, enoxaparin 1 mg/kg twice a day). Consequently, we suggest that postoperative resumption of NOACs should be done cautiously, as with postoperative resumption of LMWH bridging.7 In patients having major bowel surgery, it is likely that intake of oral medications will be limited, although this typically resolves within 24-72 hours.56 In dabigatran-treated patients, the concomitant use of drugs that decrease gastric acidity (ie, proton pump inhibitors, H2-blockers) may decrease drug absorption. Although such factors may have some effect on the bioavailability of dabigatran, this is unlikely to be clinically important.57

Determining the optimal postoperative resumption of dabigatran is based on 2 source of evidence. The first comes from studies assessing dabigatran as thromboprophylaxis after orthopedic surgery.16,58 In these studies, the starting dose of dabigatran was 110 mg on the evening after surgery followed by 220 mg once daily starting the next day. The incidence of postoperative bleeding was comparable with that in patients who received enoxaparin, 40-60 mg daily, suggesting that a lower dose of dabigatran can be safely given soon after surgery. The second source of evidence comes from the reported experience in the RE-LY trial in which postoperative resumption of dabigatran was left to the discretion of the treating physician.14 In RE-LY, dabigatran was resumed within 1 day, after 2 days, after 2-5 days, and > 5 days after surgery in 49%, 15%, 13%, and 10% of patients, respectively. For case 5, in which the patients is having major surgery, we suggest resuming dabigatran at 50% of the total daily dose (ie, 150 mg once daily) for the first 2 days after surgery followed by a full-dose dabigatran regimen (ie, 150 mg twice a day) thereafter. An alternative approach is to use the 75 mg once daily dabigatran dose during the initial 1-2 days after surgery, especially if there is greater than expected bleeding. Both of these approaches are empiric and require validation in prospective studies. Our proposed approach to postoperative resumption of dabigatran is summarized in Table 5.

Postoperative resumption of new oral anticoagulants: a suggested management approach

| Drug . | Low bleeding risk surgery . | High bleeding risk surgery . |

|---|---|---|

| Dabigatran | Resume on day after surgery (24 h postoperative), 150 mg twice daily | Resume 2-3 days after surgery (48-72 h postoperative), 150 mg twice daily* |

| Rivaroxaban | Resume on day after surgery (24 h postoperative), 20 mg once daily | Resume 2-3 days after surgery (48-72 h postoperative), 20 mg once daily† |

| Apixaban | Resume on day after surgery (24 h postoperative), 5 mg twice daily | Resume 2-3 days after surgery (48-72 h postoperative), 5 mg twice daily† |

| Drug . | Low bleeding risk surgery . | High bleeding risk surgery . |

|---|---|---|

| Dabigatran | Resume on day after surgery (24 h postoperative), 150 mg twice daily | Resume 2-3 days after surgery (48-72 h postoperative), 150 mg twice daily* |

| Rivaroxaban | Resume on day after surgery (24 h postoperative), 20 mg once daily | Resume 2-3 days after surgery (48-72 h postoperative), 20 mg once daily† |

| Apixaban | Resume on day after surgery (24 h postoperative), 5 mg twice daily | Resume 2-3 days after surgery (48-72 h postoperative), 5 mg twice daily† |

For patients at high risk for thromboembolism, consider administering a reduced dose of dabigatran (eg, 110-150 mg once daily) on the evening after surgery and on the following day (first postoperative day) after surgery.

Consider a reduced dose (ie, rivaroxaban 10 mg once a day or apixaban 2.5 mg twice a day) in patients at high risk for thromboembolism.

Case 6

A 75-year-old man with atrial fibrillation and CHADS2 score of 2 (age, hypertension) is receiving rivaroxaban, 20 mg once daily and is scheduled for laparoscopic colon resection with spinal anesthesia. His renal function is normal.

In patients who are receiving the rivaroxaban or apixaban, the preoperative drug interruption will be predicated on the drug elimination half-lives (8-9 hours for rivaroxaban, 7-8 hours for apixaban) and the drug dependence on renal clearance (33% for rivaroxaban, 25% for apixaban).59,60 As shown in Table 4, we suggest for case 6 that rivaroxaban is stopped 2 days before surgery (ie, skip 1 dose) as this would correspond to approximately 4 half-lives expired and a minimal (∼ 6%) residual anticoagulant effect at surgery. A longer duration of interruption is probably required in patients with impaired renal function, but there are no published studies relating to the preoperative interruption of rivaroxaban and apixaban in such patients.

For the postoperative management of rivaroxaban- and apixaban-treated patients, we suggest the same approach as with dabigatran-treated patients in that resumption of a treatment-dose regimen should not be initiated too soon after surgery. As shown in Table 5, we suggest using a low-dose regimen for the first 2 to 3 days in patients undergoing major surgery followed by a treatment-dose regimen thereafter. For case 6, this implies resuming rivaroxaban 10 mg once daily for 2 days, starting on the morning after surgery, and increasing to 20 mg once daily thereafter. In patients undergoing less invasive surgery, we suggest resuming a treatment-dose regimen the day after the surgery or procedure but at least after 24 hours have elapsed to allow sufficient time for wound hemostasis.

Perioperative laboratory monitoring

Perioperative laboratory monitoring of NOAC-treated patients is not routinely required given their relatively rapid offset of action and predictable pharmacokinetics but there may be clinical situations, for example, in patients receiving spinal anesthesia, where there is a need for laboratory confirmation of no significant residual anticoagulant effect so that the patient may safely proceed to surgery.

If there is need to determine a residual anticoagulant effect of dabigatran before surgery, a dilute thrombin time assay (eg, Hemoclot) may be the most reliable test.61 If such testing is not available, a normal activated partial thromboplastin time and normal thrombin clotting time are probably indicative of no residual anticoagulant effect.12,62 However, because the thrombin clotting time is very sensitive to small amounts of the anticoagulant effect of dabigatran, a normal activated partial thromboplastin time coupled with a near-normal thrombin clotting time is likely to also indicate that surgery and spinal anesthesia can be safely performed. Although some data exist for the use of the ecarin clotting time as a measure of dabigatran's activity, the assay is not used in routine clinical practice. Determining whether there is a significant anticoagulant effect of rivaroxaban or apixaban before surgery is probably best done with an appropriately calibrated antifactor Xa assay, such as Rotachrome, because these drugs have minimal effect on the activated partial thromboplastin time and unpredictable effects on the prothrombin time.63,64

Need for NOAC perioperative bridging anticoagulation

The rapid offset and onset of action of NOACs should obviate the need for perioperative bridging anticoagulation for many patients. However, there may be a role for 2-3 days of a low-dose LMWH bridging regimen (eg, enoxaparin 40 mg once daily) in postoperative patients who are unable to take oral medications. In addition, an extended period of bridging, for example with therapeutic-dose LWMH (eg, enoxaparin, 1 mg/kg twice a day), may be warranted in patients with gastric resection or postoperative ileus in whom NOAC bioavailability may be affected over a prolonged period.

Conclusions

The periprocedural management of patients on chronic oral anticoagulant therapy (including the VKA warfarin and more recently the NOACs, such as the direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran and direct factor Xa inhibitors rivaroxaban and apixaban) is a common but complex clinical problem, with little high quality data to inform clinical practice. A careful assessment of patient- and procedural-related risks of thrombosis and bleeding must be done to develop a thoughtful periprocedural antithrombotic strategy. The patient cases illustrate that a patient's thromboembolic risk should drive whether there is a need for an aggressive periprocedural antithrombotic strategy (such as the use of heparin bridging therapy in the case of warfarin or discontinuing NOACs closer to the time of surgery), whereas it is the procedural bleed risk that determines how that strategy is used in the postprocedural setting (such delayed reinitiation of heparin bridging therapy or the NOACs).

Most minor procedures, such as dental, dermatologic, and ophthalmologic procedures, can be safely undergone while a patient is on warfarin within the specified target INR range and probably the NOACs in this setting. For major or high bleed risk procedures that necessitate interruption of oral anticoagulant therapy, heparin bridging therapy using a standardized protocol should be reserved only for patients at high thromboembolic risk and for a minority of patients at intermediate thromboembolic risk. Depending on procedural bleed risk and hemostasis, postprocedure reinitiation of bridging therapy for most major surgeries should include delayed resumption for a full 48-72 hours of treatment-dose therapy, using a stepwise approach from prophylactic to treatment doses, or avoiding bridging therapy altogether during reinitiation of warfarin. For the NOACs, the timing of postprocedural reinitiation should also depend on procedural bleed risk, hemostasis, and patient's renal function (especially in the case of dabigatran), with either delayed resumption of full-dose or stepwise resumption from prophylactic to full dose in cases of high bleed risk procedures. Given the pharmacokinetic profiles of the NOACs, heparin bridging therapy is unlikely to be useful except in cases where patients cannot tolerate oral medications postoperatively.

There is a compelling need for further clinical research to allow more evidence-based recommendations for periprocedural antithrombotic therapy. There are 2 ongoing large placebo-controlled trials that should inform clinicians as to the safety and efficacy of LMWH bridging therapy. There are also large multinational registries and emerging clinical data from the large phase 3 studies of the NOACs that should provide periprocedural-related outcomes with these agents using standardized protocols.

Authorship

Contribution: A.C.S. and J.D.D. wrote and reviewed the manuscript and approved each other's sections within the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: There is no financial reimbursement from any organization for this work. A.C.S. has worked as a consultant and received honoraria from Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bayer, Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Sanofi-Aventis. He also has worked as a member of the Drug Safety Monitoring Board for a study with Portola and as a Steering Committee member for a study with Bayer. J.D.D. has worked as a consultant to Boehringer-Ingelheim, Ortho-Janssen, and AGEN Biomedical. He has worked as a prior advisory board participant for Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bayer, Astra-Zeneca, Sanofi, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. He has participated in event adjudication committees for Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Sanofi, and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Correspondence: Alex C. Spyropoulos, Department of Medicine, Division of Hematology/Oncology, University of Rochester Medical Center, 601 Elmwood Ave, Rochester, NY 14642; e-mail: Alex_Spyropoulos@URMC.Rochester.edu.