Abstract

The costimulatory effects of CD27 on T lymphocyte effector function and memory formation has been confined to evaluations in mouse models, in vitro human cell culture systems, and clinical observations. Here, we tested whether CD27 costimulation actively enhances human T-cell function, expansion, and survival in vitro and in vivo. Human T cells transduced to express an antigen-specific chimeric antigen receptor (CAR-T) containing an intracellular CD3 zeta (CD3ζ) chain signaling module with the CD27 costimulatory motif in tandem exerted increased antigen-stimulated effector functions in vitro, including cytokine secretion and cytotoxicity, compared with CAR-T with CD3ζ alone. After antigen stimulation in vitro, CD27-bearing CAR-T cells also proliferated, up-regulated Bcl-XL protein expression, resisted apoptosis, and underwent increased numerical expansion. The greatest impact of CD27 was noted in vivo, where transferred CAR-T cells with CD27 demonstrated heightened persistence after infusion, facilitating improved regression of human cancer in a xenogeneic allograft model. This tumor regression was similar to that achieved with CD28- or 4-1BB–costimulated CARs, and heightened persistence was similar to 4-1BB but greater than CD28. Thus, CD27 costimulation enhances expansion, effector function, and survival of human CAR-T cells in vitro and augments human T-cell persistence and antitumor activity in vivo.

Introduction

The genetic engineering of T cells to express chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) has emerged as an attractive “off-the-shelf” approach for generating tumor antigen-specific T cells for adoptive immunotherapy. CARs couple the high-affinity binding of antibodies with the signaling domains of the TCR CD3ζ chain for antigen-specified triggering of T-cell activation similar to the endogenous TCR.1 In early phase 1/2 trials, adoptive transfer of CAR-redirected T cells (CAR-T) did not induce tumor regression because of the poor persistence of the gene-modified T cells in vivo,2,3 consistent with the finding that persistence of tumor antigen-specific T cells after adoptive transfer correlates with the regression of tumor in patients with advanced metastatic cancer.4 The addition of costimulatory domains, including the intracellular domain of CD28 and tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) family members, CD134 (OX-40), inducible costimulator, and CD137 (4-1BB), into CARs can significantly augment the ability of these receptors to stimulate cytokine secretion, promote T-cell survival and enhance net antitumor efficacy in preclinical animal models of solid tumors and leukemia that lack cognate costimulatory ligands.5-12 Costimulated CAR therapy is now demonstrating promising clinical results in patients with lymphoma.13,14

CD27 (also known as TNFRSF7) is a member of the TNFR superfamily, whose expression is constitutive by human CD8 and CD4 T cells, natural killer T cells, natural killer-cell subsets, and hematopoietic progenitors and induced in FOXP3+ CD4 T-cell and B-cell subsets. Its ligand, CD70, is transiently expressed by activated T and B lymphocytes and mature dendritic cells. CD27 signaling plays a costimulatory role in T-cell activation yet appears to be dispensable for immune development because CD27−/− mice are immunocompetent, lack overt autoimmune symptoms, and respond to viral infection; however, T-cell memory responses in these mice are impaired in formation, kinetics of response, and cell number, which has been attributed to the impact of CD27 on activated T-cell survival.15,16 Similarly, T-cell priming in the absence of CD70 interaction with CD27 results in abortive clonal expansion, dysfunctional antitumor responses, and no CD8+ T-cell memory.17

The role of CD27 signaling in human T-cell activation, survival, and memory formation is less clear. In patients responding to adoptive T-cell therapy, the absolute number of CD27+ antigen-specific T cells that persist in the blood after infusion is remarkably stable,18 implying that the CD27 subset present in the early aftermath of infusion is the precursor to the emergent memory pool. Response to adoptive T-cell therapy is also associated with the transfer of high numbers of T cells expressing CD27 costimulatory receptor.19 Whether CD27 costimulatory signaling facilitates improved human T-cell survival, memory formation, and antitumor response in vivo or is a functionally dispensable marker for the evolving human T-cell memory pool is not known.

To investigate the functional role of CD27 in human T-cell memory development and antitumor function in vivo, we took advantage of the CAR approach and gene transfer technology to develop human T cells bearing a tumor antigen-specific scFv-based CAR fused with an intracellular CD3ζ signaling domain alone or in tandem with a CD27 signaling domain. We tested whether the addition of CD27 signaling to CAR-T cells promoted antigen-induced proliferation, antiapoptosis Bcl-XL protein expression, proinflammatory cytokine production, and cytolytic functions in vitro and evaluated whether transfer of CD27-containing CAR-T cells into tumor-bearing mice resulted in improved human T-cell survival and antitumor efficacy in a xenogeneic model of human cancer. We further compared CD27 with CD28 and CD137 (4-1BB) costimulation in CAR-T cells in vivo. Our results support the notion that CD27 promotes primary human T-cell survival in vivo and serve to rationalize the incorporation of CD27 costimulatory modules in the creation of antigen-specific CAR-T therapy.

Methods

CAR construction

CAR backbone constructs were generated as previously described.5 The anti-FR scFv sequence was derived from MOv19,20,21 a monoclonal antibody directed against folate receptor-α (FR). MOv19 scFv22,23 was amplified by use of the following primers: 5′-GCGGGATCCTCTAGAGCGGCCCAGCCGGCCATGGCCCAGGTG-3′ (BamHI is underlined) and 5′-GCGGCTAGCGGCCGCCCGTTTTATTTCCAACTTTGTCCCCCC-3′ (NheI is underlined) and cloned into the CAR backbone vector.5 The CD27 (amino acids 213-260) or CD314 (NKG2D, amino acids 1-51) intracellular domain was amplified from cDNA with the High Capacity RNA-to-cDNA Kit (Applied Biosystems) from total RNA isolated from activated T cells by the Trizol method and fused to a CD8α hinge-TM and CD3ζ fragment via overlap extension PCR. The primer sequences for FR-27z CAR construction are summarized in Table 1. The insert was then digested with XbaI and SalI and ligated into pELNS, a third-α generation self-inactivating lentiviral expression vector, based on pRRL-SIN-CMV-eGFP-WPRE,24 containing the EF-1α promoter. FR-BBz CAR constructs were described previously,25 as was the -28z CAR backbone into which MOv19 was cloned.5 The CD19-27z CAR was constructed as described previously by the use of a CD19 CAR template provided by Michael Milone (University of Pennsylvania).10 High-titer replication-defective lentiviral vectors were produced and concentrated as previously described.26

Primer sequences for FR-27z CAR construction

| Primer name . | Primer sequence (5′-3′) . |

|---|---|

| CD8a Hinge + TM F | ata gct agc accacgacgccagcgccgcgaccaccaac (NheI) |

| CD8a Hinge + TM R | gca gtaaagggtgataaccagtgacag |

| CD27 ICD F | gttatcaccctttactgccaacgaaggaaatatagatc |

| CD27 ICD R | gggggagcaggcaggctccggttttcg |

| CD3 zeta F | ccggagcctgcctgctcccccagagtgaagttcagcagg |

| CD3 zeta R | atagtcgacttagcgagggggcagggcctg (SalI) |

| Primer name . | Primer sequence (5′-3′) . |

|---|---|

| CD8a Hinge + TM F | ata gct agc accacgacgccagcgccgcgaccaccaac (NheI) |

| CD8a Hinge + TM R | gca gtaaagggtgataaccagtgacag |

| CD27 ICD F | gttatcaccctttactgccaacgaaggaaatatagatc |

| CD27 ICD R | gggggagcaggcaggctccggttttcg |

| CD3 zeta F | ccggagcctgcctgctcccccagagtgaagttcagcagg |

| CD3 zeta R | atagtcgacttagcgagggggcagggcctg (SalI) |

Restriction enzyme recognition sites are underlined.

CAR indicates chimeric antigen receptor; F, forward; ICD, intracellular domain; R, reverse; and TM, transmembrane.

T cells

Primary human CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were isolated from healthy volunteer donors after leukapheresis by negative selection and purchased from the Human Immunology Core at University of Pennsylvania. All specimens were collected under a University Institutional Review Board-approved protocol, and written informed consent was obtained from each donor in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. T cells were cultured in complete media (RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin sulfate, 10mM HEPES) and stimulated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 mAbs–coated beads (Invitrogen) as described.27 At 12-24 hours after activation, cells were transduced with lentiviral vectors at MOI of ∼ 5-10. CD4+ and CD8+ T cells used for in vivo experiments were mixed at 1:1 ratio, activated, and transduced. Human recombinant IL-2 (Novartis) was added every other day to a 50 IU/mL final concentration and a 0.5-1 × 106 cells/mL cell density was maintained. T cells were cultured for ∼ 14 days after stimulation to a resting state as determined by decreased growth kinetics and cell size (∼ 250 fL) via use of the Multisizer3 Coulter Counter (Beckman Coulter). Engineered cells were then adjusted to equalize the frequency of transgene expressing cells and level of surface CAR expression (mean fluorescence intensity) before functional assays.

Cell lines

Lentivirus packaging was performed in the immortalized normal fetal renal 293T cell line purchased from ATCC. Mycoplasma-free human cancer cell lines used in immune-based assays include the established ovarian cancer cell lines SKOV3, OVCAR8, OVCAR4, A1847, OVCAR3, OVCAR5, C30, and PEO-1 and breast cancer cell lines SKBR3, MCF7, MDA-231, and MDA-468. For bioluminescence assays, target cancer cell lines were transduced to express firefly luciferase (fLuc) with lentivirus and validated for positive expression by bioluminescence imaging. The mouse malignant mesothelioma cell line, AE17 (provided by Steven Albelda, University of Pennsylvania), was transduced to express FR (AE17.FR) with lentivirus. CD19-expressing K562 (CD19+K562) cells, a human erythroleukemic cell line, were provided by Michael Milone (University of Pennsylvania).

Cytokine release assays

Cytokine release assays were performed by coculture of 105 T cells with 105 target cells per well in triplicate in 96-well round bottom plates in a 200-μL volume of complete media. After ∼ 24 hours, coculture supernatants were assayed for the presence of IFN-γ with an ELISA Kit (Biolegend). Values represent the mean of triplicate wells. IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, IFN-γ, and TNF-α cytokines were measured by flow cytometry with Cytometric Bead Array (BD Biosciences).

Cytotoxicity assays

For the cell-based bioluminescence assay, 5 × 104 firefly Luciferase expressing (fLuc+) tumor cells were cultured with complete media in the presence of different ratios of transduced T cells with the use of a 96-well Microplate (BD Biosciences). After incubation for ∼ 20 hours at 37°C, each well was filled with 50 μL of DPBS resuspended with 1 μL of D-luciferin (0.015 g/mL) and imaged with the Xenogen IVIS Spectrum. Percent tumor cell viability was calculated as the mean luminescence of the experimental sample minus background divided by the mean luminescence of the input number of target cells used in the assay minus background times 100. All data are represented as a mean of triplicate wells. For extended-duration killing assays, tumor cells were labeled with carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE; Molecular Probes Inc) and then cultured with T cells as described previously. FACS analysis was performed with the use of forward and side scatter gating to determine viable cells, whereas CFSE and CD3 staining was used to distinguish T cells from unlabeled tumor cells.

Flow cytometric analysis

The following mAbs were used for phenotypic analysis: allophycocyanin (APC)–Cy7 mouse anti–human CD3; FITC-anti–human CD4; APC-anti–human CD8; PE-anti–human CD45; FITC-anti–human CD45RO; PE-anti–human CD62L; PE-anti–human CD27; and FITC-anti–human CD28 (BD Biosciences). In transfer experiments, blood was obtained via retro-orbital bleeding and stained for the presence of human CD45, CD4, and CD8 T cells. Human CD45+-gated, CD4+, and CD8+ subsets were quantified with the TruCount tubes (BD Biosciences) per manufacturer's instructions. Spleens pooled from each group were homogenized in RPMI cell culture medium. RBCs were lysed by adding 1× FACS Lysing Solution (BD Biosciences). Cells were washed in FACS buffer (1× PBS, 2% FCS), and 1 × 106 cells per sample were analyzed for transferred T cells phenotype.

Tumor cell surface expression of FR was detected by Mov18/ZEL antibody (Enzo Life Sciences). CD70 (CD27 ligand) expression on SKOV3 cells was detected by FITC-anti–human CD70 antibody (BD Biosciences). CAR expression was detected by biotin-labeled Protein L (GeneScript) at 100 ng per 106 cells followed by incubation with APC-conjugated streptavidin or PE-conjugated goat anti–mouse IgG F(ab′)2 (Jackson Immuno-Research Laboratories). PE-conjugated antiBcl-XL antibody was purchased from Southern Biotech. Isotype-matched control Abs were used in all analyses. Flow cytometric data were analyzed by FlowJo Version 7.2.5 software.

T-cell proliferation, expansion, and apoptosis

For cell division, 2 × 107 T cells in PBS were labeled with 2.5μM CFSE for 5 minutes at room temperature. Labeled cells were cocultured with tumor cells at 2:1 ratio in the absence of exogenous IL-2. After 5 days, cells were stained with CD3 and analyzed for CFSE dilution by FACS analysis. For expansion, viable T cells were cocultured with tumor cells at 1:1 ratio in the absence of IL-2, and T-cell counts were determined by the Multisizer 3 Coulter Counter (Beckman Coulter) and Trypan blue exclusion on day 5 and 10. For apoptosis assays, T cells were cocultured with tumor cells at 2:1 ratio in the absence of IL-2. After 3 days, T cells were detected by simultaneous staining with anti-CD3 antibody, annexin V–FITC, and 7-AAD-PerCP-Cy5.5, according to the manufacturer's instructions (BD Pharmingen).

Xenograft model of ovarian cancer

Animals were obtained from the Stem Cell and Xenograft Core of the Abramson Cancer Center, University of Pennsylvania. Then, 8- to 12-week-old nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficient/γ-chain−/− (NSG) mice were bred, treated, and maintained under pathogen-free conditions in-house under University of Pennsylvania Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee–approved protocols. Female NSG mice were inoculated subcutaneously with 3 × 106 SKOV3 fLuc+ cells on the flank on day 0. Five mice were randomized per group before treatment. After tumors became palpable, human primary T cells (CD4+ and CD8+ cells mixed at 1:1 ratio) were activated and transduced as described previously. After 2 weeks' expansion, when tumor burden was ∼ 250-300 mm3, mice were injected with 107 CAR-T cells (∼ 2 × 107 at 50% CAR+) intratumorally or intravenously and again 5-7 days later. Tumor dimensions were measured with calipers, and tumor volumes calculated with the following formula: V = 1/2(length × width2), where length is greatest longitudinal diameter and width is greatest transverse diameter. Animals were imaged before T-cell transfer and approximately every 2 weeks thereafter. Tumors were resected immediately after the animals were euthanized, which was 25 days after first T-cell dose for size measurement.

Bioluminescence imaging

Imaging of tumor was performed with the Xenogen IVIS imaging system and the photons emitted from fLuc+ cells within the animal body were quantified with the Living Image Version 3.0 software (Xenogen). To summarize in brief, mice bearing SKOV3 fLuc+ tumor cells were injected intraperitoneally with D-luciferin (150 mg/kg stock, 100 μL of D-luciferin per 10 g of mouse body weight) suspended in PBS, and imaged under isoflurane anesthesia after ∼ 10 minutes. Pseudocolor images representing light intensity (blue, least intense; red, most intense) were generated with Living Image. Imaging findings were confirmed at necropsy.

Statistical analysis

The data are reported as means and SD. Statistical analysis was performed by the use of 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA for the tumor burden (tumor volume, photon counts). Student t test was used to evaluate differences in absolute numbers of transferred T cells, cytokine secretion, and specific cytolysis. GraphPad Prism 4.0 (GraphPad Software) was used for the statistical calculations. P < .05 was considered significant.

Results

CAR construction and T-cell transduction

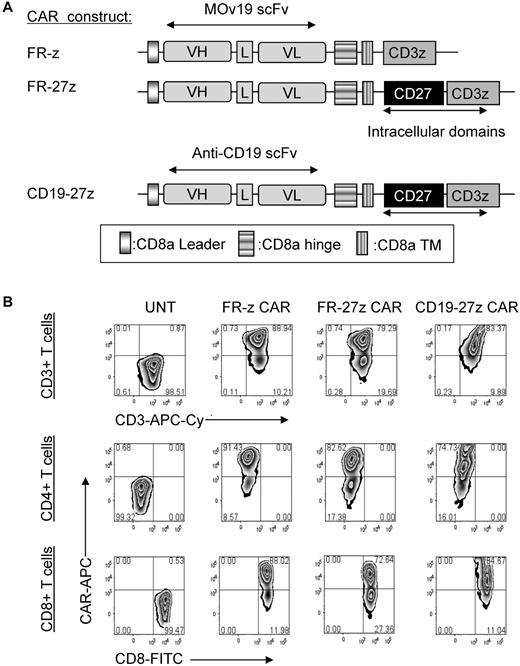

FR-specific CARs were constructed containing the mouse anti-human scFv MOv19, which has high affinity for FR (108-109 M−1).20,21,23 FR is a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored protein that is overexpressed on the surface of cancer cells in a wide array of epithelial malignancies, including ovarian, lung, breast, colorectal, renal, and other solid cancers but limited in normal tissues.20,28-34 FR CAR constructs were composed of the MOv19 scFv linked to a CD8α hinge and transmembrane region, followed by a CD3ζ signaling moiety alone (FR-z) or in tandem with the CD27 intracellular signaling motif (FR-27z; Figure 1A). A CD19-specific CAR containing CD3ζ and CD27 signaling motifs in tandem (CD19-27z) was constructed to control for antigen specificity. CAR constructs were subcloned into the pELNS lentiviral vector, where transgene expression is driven off the EF-1α promoter.

CAR constructs and expression of CD27 containing FR CAR or CD19 CAR on primary human CD4 and CD8 T cells. (A) Schematic representation of anti-FR MOv19 scFv-based CAR constructs containing the CD3ζ cytosolic domain alone (FR-z CAR) or in combination with CD27 intracellular domain (FR-27z CAR). CD19-27z CAR was also constructed and used as an antigen specific control. VL indicates variable light chain; L, linker; VH, variable heavy chain; and TM, transmembrane region. (B) Both primary human CD4 and CD8 T cells can efficiently express either FR-specific CARs or CD19-specific CAR as measured by flow cytometry. A viable CD3+ lymphocyte gating strategy was used. UNT indicates untransduced cells.

CAR constructs and expression of CD27 containing FR CAR or CD19 CAR on primary human CD4 and CD8 T cells. (A) Schematic representation of anti-FR MOv19 scFv-based CAR constructs containing the CD3ζ cytosolic domain alone (FR-z CAR) or in combination with CD27 intracellular domain (FR-27z CAR). CD19-27z CAR was also constructed and used as an antigen specific control. VL indicates variable light chain; L, linker; VH, variable heavy chain; and TM, transmembrane region. (B) Both primary human CD4 and CD8 T cells can efficiently express either FR-specific CARs or CD19-specific CAR as measured by flow cytometry. A viable CD3+ lymphocyte gating strategy was used. UNT indicates untransduced cells.

When gene transfer technology established for clinical application was used, lentiviral vectors efficiently transduced primary human T cells to express anti-FR or CD19 CARs (Figure 1B). Transduced cells showed a CD45RO+CD62L+CD28+CD27+ central memory-like phenotype (supplemental Figure 1A, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). For in vitro assays, whole CD3+ cells or enriched CD8+ or CD4+ T cells were transduced independently with CAR. Reproducibly, the efficiency of cell transduction with CAR was high (> 70%), as assessed by flow cytometry, with transduction efficiency with FR-z CAR being identical or slightly greater than with FR-27z CAR. The frequency of CAR-expressing T cells was equalized before all functional assays.

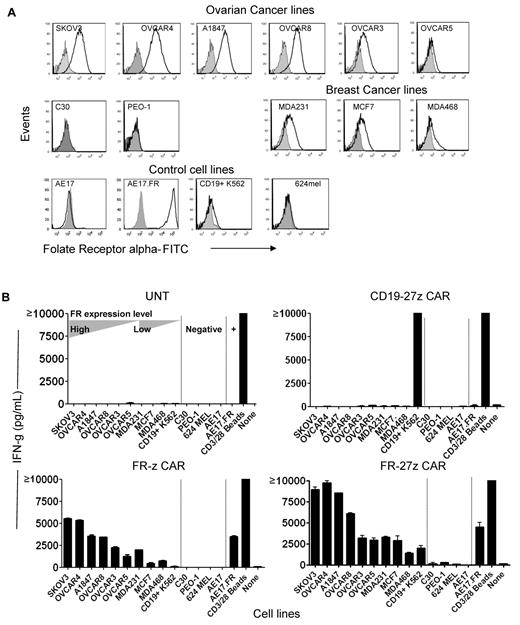

CAR T cells with CD27 signaling exert enhanced antigen-specific reactivity in vitro

Ovarian and breast cancers frequently express FR.20,35 A panel of established human ovarian and breast cancer cell lines that express surface FR at various levels was selected for assays (Figure 2A). Flow cytometry results confirmed that ovarian cancer lines SKOV3, A1847, OVCAR8, OVCAR4, OVCAR3, and OVCAR5 and breast cancer cell lines MCF7, MDA231, and MDA468 all expressed surface FR protein, as did control lines AE17.FR (a mouse mesothelioma cell line36 engineered to express human FR) and CD19+ K562 (a human erythromyeloblastoid leukemia cell line engineered to express human CD19). Two ovarian cancer lines, C30 and PEO-1, were negative for FR, as were the parental AE17 line and the 624 melanoma line.

Enhanced immune recognition of tumor cells by CD27-bearing CAR-T cells. (A) FR surface expression on human ovarian cancer and breast cancer cell lines by flow cytometry. FR-specific mAb MOv18 was used to measure FR expression on tumor cell lines (open empty histogram), compared with a matched isotype Ab control (filled gray histogram). (B) Antigen-specific cytokine production by FR CAR-transduced T cells. IFN-γ secretion of FR-z and 27z CAR-transduced T cells after 20 hours' coculture with the indicated tumor lines at a 1:1 ratio. Untransduced T cells (UNT) and CD19-27z CAR-T cells were used as negative controls. Anti-CD3/28 beads stimulation served as positive control. CD19+K562 cell line was used as positive target control for CD19 CAR. Results are expressed as a mean and SD of triplicate wells from 1 of at least 3 separate experiments.

Enhanced immune recognition of tumor cells by CD27-bearing CAR-T cells. (A) FR surface expression on human ovarian cancer and breast cancer cell lines by flow cytometry. FR-specific mAb MOv18 was used to measure FR expression on tumor cell lines (open empty histogram), compared with a matched isotype Ab control (filled gray histogram). (B) Antigen-specific cytokine production by FR CAR-transduced T cells. IFN-γ secretion of FR-z and 27z CAR-transduced T cells after 20 hours' coculture with the indicated tumor lines at a 1:1 ratio. Untransduced T cells (UNT) and CD19-27z CAR-T cells were used as negative controls. Anti-CD3/28 beads stimulation served as positive control. CD19+K562 cell line was used as positive target control for CD19 CAR. Results are expressed as a mean and SD of triplicate wells from 1 of at least 3 separate experiments.

To evaluate the impact of CD27 costimulation on antigen-specific antitumor function of CAR-T cells in vitro, engineered human T cells and cancer cells were cocultured and T-cell reactivity measured by proinflammatory cytokine secretion. FR-z or FR-27z CAR-T cells recognized FRpos ovarian and breast cancer lines and secreted high levels of IFN-γ, which was associated with the level of FR expression by tumor cells but not when stimulated with FRneg cell lines (Figure 2B). Invariably, increased quantities of secreted IFN-γ were detected when FR-27z CAR-T cells where stimulated with the various FRpos target cells, relative to FR-z CAR-T cells. FR-27z and FR-z CARs functioned in both primary human CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, with CD8+ T cells producing more Th-1 type cytokines than CD4+ T cells (supplemental Figure 2). CD8+ FR-27z CAR-T cells also secreted greater levels of TNF-α and IL-2 than FR-z CAR-T cells when stimulated with FRpos cancer cells (supplemental Figure 2). CD4+ and CD8+ CAR-T cells produced low levels of IL-4 and IL-10, which were uniformly lower in FR-27z CAR-T cells compared with FR-z, indicating that CD27 signaling reinforces the Th-1 response.

When the CD27 domain was replaced by the CD314 endodomain, which is similar in length but has no intrinsic signaling capacity,37,38 FR-314z CAR-T cells failed to increase IFN-γ secretion after coculture with FR+ SKOV3 cells, compared with FR-z (supplemental Figure 3), confirming that the costimulatory CAR effects are not because of simple extension of the intracellular domain.39 CD19-27z CAR-T cells did not produce IFN-γ, except when coincubated with CD19+ K562 cells, and untransduced T cells did not secrete cytokine when stimulated with FRpos cancer cells, illustrating the requirement for antigen specificity for CAR-T cell activity.

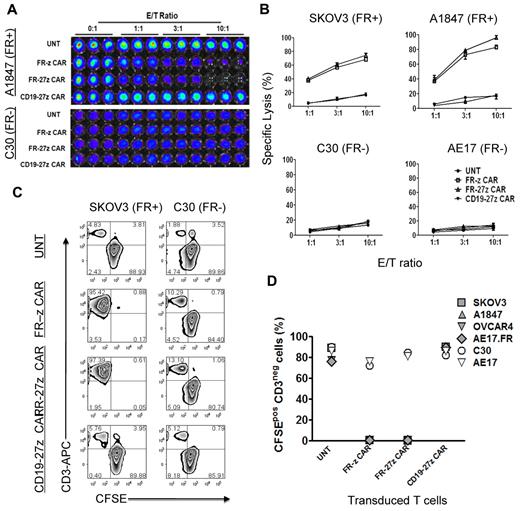

We next evaluated the antigen-specific cytolytic potential of FR-specific CD8+ CAR-T cells in vitro using overnight luminescence and 5-day coculture assays. CAR-T cells were cocultured with FRpos SKOV3 and A1847 cancer cells or FRneg C30 and AE17 cells expressing firefly luciferase (fLuc+) and assessed for bioluminescence after overnight culture. Representative luminescence results shown in Figure 3A reveal that both FR-z and FR-27z CAR-T cells specifically eliminated FRpos A1847 ovarian cancer cells but not FRneg C30. Untransduced or CD19-27z CAR-T cells did not lyse ovarian cancer cells, but the latter did efficiently lyse CD19+ K562 cells (supplemental Figure 4). FR-z and FR-27z CAR-T cells directly and efficiently lysed FRpos human ovarian cancer cell lines SKOV3 and A1847 but not FRneg C30 or AE17 cell lines (Figure 3B). Similar to cytokine production results, FR-27z CAR-T cells demonstrated enhanced cytotoxicity, particularly at high E/T ratios, compared with FR-z CAR-T cells, but not at lower ratios (P = .024). To assess the cytotoxic function of CAR-T cells in extended culture, CAR-T cells were cocultured with CFSE-labeled tumor cells for 5 days. Representative dot plots show that CFSE+ CD3-negative SKOV3 cancer cells, but not C30 cells, were eliminated when cultured with FR-specific CAR-T cells but control T cells (Figure 3C). Cocultures containing FR-specific CAR-T cells were dominated by CFSE-negative CD3+ human T cells that had eliminated all FRpos cancer cells tested (SKOV3, A1847, OVCAR4, AE17.FR) in extended culture, but not FRneg lines (Figure 3D).

Specific tumor cell lysis by CD27 costimulated FR-specific CAR-T cells. (A-B) CAR-transduced T-cell lytic function was tested in bioluminescent killing assay with a 96-well microplate. FR CAR-T cells killed FR+ SKOV3 and A1847 cells but showed no killing of the FR− C30 and AE17 cells at the indicated E/T ratio for ∼ 20 hours, where untransduced T cells (UNT) and CD19 CAR-T cells served as negative controls. Results are expressed as a mean and SD of triplicate wells from 1 of at least 3 separate experiments. (C) T cells were cocultured with CFSE-labeled tumor cells at a 2:1 ratio in the absence of exogenous IL-2. After 5 days of coculture, cells were collected, stained with CD3, and analyzed for CFSE dilution by FACS analysis. Both FR-z and 27z CAR-transduced T cells killed SKOV3 cells, as evidenced by the lack of CD3neg CFSEpos cells, but not C30 cells. Nontransduced T cells and CD19-27 CAR-transduced T cells did not kill ovarian cells. (D) In all extended coculture experiments, both FR-z and 27z CAR-transduced T cells eliminated the CD3neg CFSEpos FRpos tumor cells (SKOV3, A1847, OVCAR4, and AE17.FR) but not FRneg tumor cells (C30 and AE17).

Specific tumor cell lysis by CD27 costimulated FR-specific CAR-T cells. (A-B) CAR-transduced T-cell lytic function was tested in bioluminescent killing assay with a 96-well microplate. FR CAR-T cells killed FR+ SKOV3 and A1847 cells but showed no killing of the FR− C30 and AE17 cells at the indicated E/T ratio for ∼ 20 hours, where untransduced T cells (UNT) and CD19 CAR-T cells served as negative controls. Results are expressed as a mean and SD of triplicate wells from 1 of at least 3 separate experiments. (C) T cells were cocultured with CFSE-labeled tumor cells at a 2:1 ratio in the absence of exogenous IL-2. After 5 days of coculture, cells were collected, stained with CD3, and analyzed for CFSE dilution by FACS analysis. Both FR-z and 27z CAR-transduced T cells killed SKOV3 cells, as evidenced by the lack of CD3neg CFSEpos cells, but not C30 cells. Nontransduced T cells and CD19-27 CAR-transduced T cells did not kill ovarian cells. (D) In all extended coculture experiments, both FR-z and 27z CAR-transduced T cells eliminated the CD3neg CFSEpos FRpos tumor cells (SKOV3, A1847, OVCAR4, and AE17.FR) but not FRneg tumor cells (C30 and AE17).

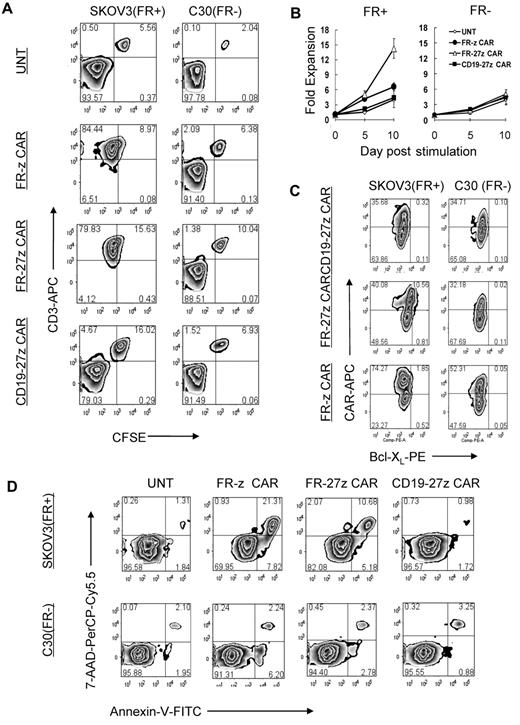

CD27 signaling improves the survival of antigen-stimulated CAR-T cells in vitro

To determine the impact of CD27 costimulation on antigen-stimulated proliferation of redirected T cells, CFSE-labeled CAR-T cells were cocultured with FRpos SKOV3 or FRneg C30 cell lines, respectively. CFSE-labeled control CD3+ T cells did not dilute CFSE or eliminate CFSEneg CD3neg tumor cells after 72 hours' incubation (Figure 4A). However, FR-z and FR-27z CAR-T cells both proliferated, and to a similar extent, in response to FRpos tumor stimulation as measured by CFSE dilution and eliminated the tumor cell fraction, in agreement with results in the preceding paragraph (Figure 3D).

CD27 costimulation enhances CAR-T–cell survival and expansion in vitro. (A) CFSE-labeled FR-z and 27z CAR-transduced T cells undergo cellular division when cocultured for 5 days with FRpos SKOV3 cells but not the FRneg C30 cells. Untransduced T cells (UNT) and CD19-27z CAR-T cells did not dilute CFSE when cocultured with either FRpos SKOV3 cells or FRneg C30 cells. (B) FR CAR-T cell expansion was measured in response to stimulation with FRpos target cells at a 1:2 ratio in the absence of exogenous IL-2. Viable (trypan blue exclusion) cell counting results showed that FR-27z CAR-T cells underwent increased numerical expansion after 10 days, compared with FR-z CAR-T cells. Counts reflect mean ± SD for triplicate cultures of 2 independent assays. (C) Bcl-XL expression by FR- or CD19-specific CAR CD8 T cells was examined after 3 days of coculture with SKOV3 or C30 cells. Bcl-XL expression was preferentially increased in FR-27z CAR T-cell populations, compared with FR-z CAR+ T cells after stimulation with FRpos tumor cells. One representative FACS analysis is shown (n = 3). (D) CD27 costimulation protects against antigen-induced cell death. Apoptotic T cells were detected by simultaneous staining with annexin V (AV)–FITC and 7-AAD-PerCP-cy5.5 at 72 hours after indicated tumor cell stimulation. Apoptosis was quantified in percentages of living (AV−/7AAD−), early apoptotic (AV+/7AAD−), late apoptotic (AV+/7AAD+), and necrotic (AV−/7AAD+) cells. One representative experiment of 3 is shown.

CD27 costimulation enhances CAR-T–cell survival and expansion in vitro. (A) CFSE-labeled FR-z and 27z CAR-transduced T cells undergo cellular division when cocultured for 5 days with FRpos SKOV3 cells but not the FRneg C30 cells. Untransduced T cells (UNT) and CD19-27z CAR-T cells did not dilute CFSE when cocultured with either FRpos SKOV3 cells or FRneg C30 cells. (B) FR CAR-T cell expansion was measured in response to stimulation with FRpos target cells at a 1:2 ratio in the absence of exogenous IL-2. Viable (trypan blue exclusion) cell counting results showed that FR-27z CAR-T cells underwent increased numerical expansion after 10 days, compared with FR-z CAR-T cells. Counts reflect mean ± SD for triplicate cultures of 2 independent assays. (C) Bcl-XL expression by FR- or CD19-specific CAR CD8 T cells was examined after 3 days of coculture with SKOV3 or C30 cells. Bcl-XL expression was preferentially increased in FR-27z CAR T-cell populations, compared with FR-z CAR+ T cells after stimulation with FRpos tumor cells. One representative FACS analysis is shown (n = 3). (D) CD27 costimulation protects against antigen-induced cell death. Apoptotic T cells were detected by simultaneous staining with annexin V (AV)–FITC and 7-AAD-PerCP-cy5.5 at 72 hours after indicated tumor cell stimulation. Apoptosis was quantified in percentages of living (AV−/7AAD−), early apoptotic (AV+/7AAD−), late apoptotic (AV+/7AAD+), and necrotic (AV−/7AAD+) cells. One representative experiment of 3 is shown.

Because T-cell division does not adequately measure the extent of overall cell expansion, which encompasses both cell proliferation and apoptosis, viable cell counting was performed. In response to FRpos tumor stimulation, FR-27z CAR-T cells underwent increased numerical expansion after 10 days, compared with FR-z CAR-T cells, suggesting a survival advantage for cells receiving CD27 costimulation (Figure 4B). Nonspecific stimulation with FRneg tumor cells did not induce substantial cell expansion. CD27 signaling can induce expression of Bcl-XL,40,41 an antiapoptotic protein of the Bcl-2 family. When stimulated with FRpos tumor cells, more FR-27z CAR-T cells (∼ 20% of CAR+) expressed Bcl-XL compared with FR-z (∼ 2.4%) and CD19-27z CAR-T cells (∼ 0.9%; Figure 4C). Bcl-XL up-regulation was restricted to the CAR+ T-cell population, confirming dependence on antigen-specific stimulation. Consistent with these findings, more viable (7-AADneg annexin Vneg) and fewer early apoptotic (7-AADneg annexin Vpos) and late apoptotic (7-AADpos annexin Vpos) T cells were detected in cocultures of FR-27z CAR-T cells and FRpos SKOV3 tumor cells, compared with FR-z CAR-T cell cultures where apoptosis was more prevalent (Figure 4D).

CD27 promotes CAR-T cell survival and antitumor function in vivo

The addition of CD28 or CD137(4-1BB) endodomains to CARs can improve CAR-T cell persistence and antitumor function in vivo.5,25,42 To test and compare CD27 to these domains, we generated MOv19-based FR-28z and FR-BBz CARs.25 Transduced human CD4+ and CD8+ T cells efficiently expressed the various FR-specific CAR constructs (Figure 5A). CAR-T cells bearing -z, -27z, -28z, or -BBz endodomains directly and efficiently lysed FRpos SKOV3 cells in vitro but not FRneg C30 (Figure 5B). Next, immunodeficient nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficient/IL-2Rγcnull (NSG) mice were inoculated subcutaneously with fLuc+ FRpos SKOV3 human ovarian cancer cells on the hind flank and received intravenous injections of 107 CAR+ T cells on days 40 and 45 after tumor inoculation (p.i. in Figure 5C), when tumors were ∼ 250 mm3 in size and evident by bioluminescence imaging.

Comparison of FR-specific CARs with CD27, CD28, and 4-1BB costimulatory endodomain. (A) FR-specific CAR expression on primary human T cells. As shown, CD8+ T cells can efficiently express FR-specific CARs with or without CD27, CD28, and 4-1BB costimulatory endodomains as measured by flow cytometry. (B) CAR-transduced T cells showed lytic function in a bioluminescent killing assay. FR CAR-T cells killed FR+ SKOV3 but did not kill FR− C30 cells at the indicated E/T ratio more than ∼ 20 hours. Untransduced T cells (UNT) served as negative controls. Mean and SD of triplicate wells from 1 of at least 3 independent experiments is shown. (C) Bioluminescence images show fLuc+ SKOV3 tumors in NSG mice immediately before and 3 weeks after first intravenous injection of 10 × 106 CAR-T cells on days 40 and 45 after tumor inoculation. (D) Tumors in mice treated with FR-27z, -28z, and -BBz CAR-T cells regressed; tumors treated with untransduced T cells (UNT) did not regress 3 weeks after first T-cell dose (P < .0001). Arrows indicate timing of T-cell infusion. FR-z CAR-transduced T cells only slowed tumor growth (P = .015). Before infusion, CAR+ T-cell frequency (∼ 50%) and surface scFv expression level (range, 315-398 mean fluorescence intensity) was equalized. (E) Circulating human CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell counts. In contrast to CD28, CD27 and 4-1BB signaling enhances the survival of circulating human CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in vivo 3 weeks after T-cell infusion (27z vs z, P = .029; BBz vs z, P = .024; 28z vs z, P = .20). Mean cell concentration (cells/μL) ± SD for all evaluable mice in each treatment group is shown. (F) Surface CAR expression on persisting FR-specific human CD3+ T cells from blood of treated mice measured by flow cytometry. Mean CAR+ expression frequency per CD3+ T cells and SD per group is shown.

Comparison of FR-specific CARs with CD27, CD28, and 4-1BB costimulatory endodomain. (A) FR-specific CAR expression on primary human T cells. As shown, CD8+ T cells can efficiently express FR-specific CARs with or without CD27, CD28, and 4-1BB costimulatory endodomains as measured by flow cytometry. (B) CAR-transduced T cells showed lytic function in a bioluminescent killing assay. FR CAR-T cells killed FR+ SKOV3 but did not kill FR− C30 cells at the indicated E/T ratio more than ∼ 20 hours. Untransduced T cells (UNT) served as negative controls. Mean and SD of triplicate wells from 1 of at least 3 independent experiments is shown. (C) Bioluminescence images show fLuc+ SKOV3 tumors in NSG mice immediately before and 3 weeks after first intravenous injection of 10 × 106 CAR-T cells on days 40 and 45 after tumor inoculation. (D) Tumors in mice treated with FR-27z, -28z, and -BBz CAR-T cells regressed; tumors treated with untransduced T cells (UNT) did not regress 3 weeks after first T-cell dose (P < .0001). Arrows indicate timing of T-cell infusion. FR-z CAR-transduced T cells only slowed tumor growth (P = .015). Before infusion, CAR+ T-cell frequency (∼ 50%) and surface scFv expression level (range, 315-398 mean fluorescence intensity) was equalized. (E) Circulating human CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell counts. In contrast to CD28, CD27 and 4-1BB signaling enhances the survival of circulating human CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in vivo 3 weeks after T-cell infusion (27z vs z, P = .029; BBz vs z, P = .024; 28z vs z, P = .20). Mean cell concentration (cells/μL) ± SD for all evaluable mice in each treatment group is shown. (F) Surface CAR expression on persisting FR-specific human CD3+ T cells from blood of treated mice measured by flow cytometry. Mean CAR+ expression frequency per CD3+ T cells and SD per group is shown.

Transfer of FR-27z CAR-T cells by intravenous or intratumoral administration resulted in the rapid regression of established human tumor (Figure 5C-D and supplemental Figure 5A; P < .0001), which was superior to first-generation FR-z CAR therapy. FR-27z CAR–mediated regression was similar to that achieved with FR-28z and FR-BBz CAR-T cells. Although SKOV3 cells do express low levels of CD70, the CD27 ligand, FR-z CAR-T cells that expressed endogenous cell surface CD27 at the time of cell infusion had only a modest impact on tumor outgrowth, compared with animals receiving untransduced T cells (P = .015), and did not express surface CD27 3 weeks after transfer (supplemental Figure 1A). Although these observations do not define the role for endogenous CD27 in this system, it does demonstrate that enforced expression of CD27 in CAR-T cells augments their antitumor function in vivo.

Significantly greater numbers of circulating human CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were observed in tumor-treated mice receiving either FR-27z or FR-BBz CAR-T cells 3 weeks after the first T-cell dose compared with FR-z and FR-28z CAR groups (Figure 5D; P < .05). Improved engraftment of FR-27z CAR-T cells required both antigen-specific stimulation and CD27 costimulation. Persistence was not a product of constitutive CD27 activity because CD19-27z CAR-T cells did not engraft or treat tumor (supplemental Figures 6-7). Furthermore, cognate antigen recognition reinforces the persistence of CAR-T cells in vivo because mice that received FR-z CAR-T cells had increased CAR+ T-cell counts compared with mice in CD19-27z CAR-T (P = .017) or gfp T-cell groups, which had little to no detectable persistence of CAR+ T cells, respectively (supplemental Figure 6).

Notably, surface CAR expression was better maintained in the FR-28z group (Figure 5F), compared with other groups (P < .01), consistent with previous findings.12 As such, the absolute number of circulating CAR+ T cells in tumor-bearing mice administered FR-27z, FR-28z, and FR-BBz were not statistically different (P > .05) but greater than that observed in mice receiving first-generation FR-z CAR-T cells (supplemental Figure 5B).

Discussion

In this study, we elucidate a role for CD27 costimulatory function in promoting the survival of adoptively transferred human T cells in vivo and enhancing the antitumor efficacy of CAR therapy. Primary human T cells expressing a FR-specific CAR, outfitted with intracellular TCR CD3ζ and a CD27 costimulatory signaling domain in tandem, recognized and killed FR-expressing cancer cells lines in vitro and demonstrated improved antigen-dependent memory formation and antitumor potency in vivo in a mouse xenograft model of advanced cancer.

In our study, the role of CD27 costimulatory signaling in T-cell effector proliferation, activity, and survival was evaluated via incorporation of the CD27 receptor endodomain into the intracellular signaling portion of a FR-specific CAR-z construct. The addition of the CD27 signaling domain to CAR supported significant improvement in tumor antigen-specific T-cell reactivity in vitro, relative to first-generation FR-z CAR. Consistently, the production of proinflammatory cytokines such as IFN-γ by FR-27z CAR-T cells was substantially increased after coculture with all FRpos ovarian and breast cancer cell lines, compared with FR-z T cells. Interestingly, the levels of cytokine secretion measured were associated with the expression of surface FR expression by target cancer cells for both FR-27z and FR-z CAR-T cells. In overnight killing assays, provision of CD27 costimulation to CAR resulted in marginally increased cytolytic function; however, with extended coculture, both FR-27z and FR-z CARs induced complete tumor killing with no viable FR-expressing tumor cells detected. Mechanisms accounting for increased effector function by CD27 costimulated CAR-T cells in vitro are not known but appear linked in part to their ability to resist antigen-induced cell death and suggest that CAR-T cells with CD27 costimulatory capacity might demonstrate improved function and therapeutic efficacy in vivo.

With the use of in vitro assay systems, CD27 has been established as a costimulator of human T-cell responses43 ; however, its importance for immune responses and memory formation in vivo has been primarily restricted to studies in which the authors use mouse model systems. Although CD27−/− mice are immunocompetent, intranasal infection with influenza virus revealed that CD27 costimulation regulates the survival and accumulation of virus specific T cells at the site of infection independent and complementary to CD28.15,16 Moreover, T-cell memory responses are reduced in CD27−/− mice on secondary infection.15,16

Similar results have been observed in a model of CD8+ T cell–mediated cardiac allograft rejection where disruption of CD27-CD70 interactions contributes to reduced CD28-independent effector T-cell accumulation, function, and memory response.44 Alternatively, constitutive CD27 costimulatory signaling in CD70 transgenic mice promotes virus- and cancer-specific CD8+ memory T-cell formation by initially reducing effector phase contraction and supporting the maintenance of high numbers of antigen-specific T cells with increased effector function in the memory pool.45 Notably, superior cancer-specific CD8+ memory formation induced by constitutive CD27 ligation can protect CD70 transgenic mice against lethal tumor dose challenge in an IFN-γ–dependent manner.45

The intracytoplasmic domain of CD27 used in our study and triggered naturally by CD70 ligation mediates prosurvival effects through interaction with TRAF2 and activation of Jun kinase and NF-κB, which is required for optimal effector/memory CD8+ T-cell generation.46 The mechanism by which CD27 prevents activation-induced cell death and promotes T-cell survival includes the up-regulation of antiapoptotic Bcl-XL protein expression41 and resistance to Fas-mediated apoptosis.47 After stimulation in vitro, increased Bcl-XL protein expression has been observed in T cells engineered to express a CD70-specific, chimeric CD27-CD3z CAR consisting of the both the extracellular and intracellular CD27 domains.40 Consistent with this finding, we observed increased expression of Bcl-XL protein in FR-27z CAR-T cells after antigen stimulation, compared with FR-z alone. Moreover, incorporation of the CD27 intracellular signaling domain to CAR also reduced T-cell apoptosis after antigen-induced activation and consequently increased numerical expansion of transduced T cells in vitro. These results suggested that provision of CD27 costimulatory signaling through CAR engagement with cognate antigen in vivo might improve T-cell survival and numerical expansion, thereby significantly augmenting their potential for antitumor activity after adoptive transfer.

The role of CD27 on human T-cell activity and memory formation in vivo has not been formally evaluated to date. We first reported that after adoptive transfer of heterogeneous tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) to patients with metastatic melanoma in vivo, a subpopulation of CD27+ tumor antigen–specific T cells was temporally selected for in vivo, suggesting that these cells possessed a function advantage in long-term survival and that CD27+ cells detectable in the blood in the early aftermath of adoptive transfer represented the precursors to the emerging memory pool.18 These results were later reproduced at the clonal level for HIV-specific CD8+ T cells persisting after adoptive transfer.48 Similarly, a population of CD27+ HIV-specific CD8+ T cells with memory characteristics and direct effector capabilities has been observed in vivo when viral replication is inhibited with antiretroviral therapy.49 Consistent with these results, retrospective analysis of TILs administered to patients with melanoma revealed a significant association between the absolute number of administered CD27+ CD8+ TILs and the ability of those TILs to persist in vivo and mediate objective clinical response after transfer.19 Because T-cell persistence after infusion is a major factor limiting adoptive cell therapy,4 the elucidation of approaches to promote T-cell survival has the potential to significantly improve response rates in adoptive immunotherapy.

The impact of CD27 costimulation on human T-cell survival and antitumor activity was most evident in vivo, where CD27-bearing CAR-T cells facilitated superior regression of established tumors in a human ovarian cancer xenograft model compared with the marginal inhibition achieved with conventional, noncostimulated CAR-T cells. Consistent with clinical observations,4,50 tumor regression in our model was associated with enhanced T-cell persistence in vivo. Tumor regression and T-cell persistence were antigen-specific because transfer of CD19-27z T cells had no impact on tumor progression and resulted in poor persistence after intratumoral infusion. Moreover, tumor regression and T-cell persistence was increased in mice that received first-generation FR-z CAR-T cells, compared with costimulated CD19-27z CAR, demonstrating that provision of a CD27 costimulatory domain in the absence of antigen-specific ligation of the CAR does not substantially bolster T-cell survival and effector function in vivo. In this line, the greatest number of CAR+ T cells persisting in the blood 1 month after the first T-cell dose was observed in those animals administered FR-27z CAR-T cells followed by FR-z and then CD19-27z, indicating that simultaneous TCR CD3ζ signaling and CD27 costimulation triggered by CAR ligation with antigen improves on TCR signaling alone, implicating a role for CD27 costimulation in memory T-cell formation in vivo.

Our results support the notion that human T cells that are enabled to receive CD27 costimulatory signals in conjunction with CD3ζ signaling receive amplified antiapoptotic signals that facilitate enhanced effector activity and better survival in vivo, assuring the generation of stable human T-cell memory. The addition of costimulatory domains, particularly the intracellular domains of CD28, and the tumor necrosis factor receptor family members, CD134 and 4-1BB (CD137), can also significantly augment the ability of these receptors to stimulate cytokine secretion, support T-cell survival and enhance antitumor efficacy in preclinical animal models using both solid tumors and leukemia that lack the expression of their cognate costimulatory ligands.5-12

Results of comparative in vivo studies of CARs containing these various costimulatory domains demonstrated that CD137 (4-1BB), like CD27, another member of the TNFR superfamily enhances T cell antitumor activity and persistence. In contrast, CD28, which can support enhanced antitumor activity, does not support robust numerical T-cell persistence. Rather, CD28 supports stable surface CAR expression, which may be attributed in part to the inclusion of its transmembrane region in the CAR construct, as suggested previously.12 Notably, each of these costimulatory molecules can dramatically improve the activity and overcomes the limitations of first-generation CAR approaches by improving the persistence of transferred T cells in vivo. These results rationalize the clinical investigation of CD27 costimulated CAR-T cell therapy in combination with lymphodepleting pre-conditioning for the treatment of cancer. Our data further suggest that the combination of CD27 or CD137 endodomains with the CD28 signaling domain may be more effective than CD27, CD137 or CD28 alone.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs George Coukos, Silvana Canevari, Carl June, Gwenn Danet-Desnoyers, and Michael Milone for helpful discussions.

This work was supported (in part) by the Ovarian Cancer Research Fund, the Marsha Rivkin Center for Ovarian Cancer Research, and the Sandy Rollman Ovarian Cancer Foundation.

Authorship

Contribution: D.-G.S., Q.Y., M.P., and G.M.H. performed research; M.F. provided vital new reagents; D.-G.S. collected data and performed statistical analysis; D.J.P. designed research and interpreted data; and D.S. and D.J.P. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Daniel J. Powell Jr, University of Pennsylvania, Rm 1313 BRB II/III, 421 Curie Blvd, Philadelphia, PA 19104; e-mail: poda@mail.med.upenn.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal