Abstract

Erythroid (red blood) cells are the first cell type to be specified in the postimplantation mammalian embryo and serve highly specialized, essential functions throughout gestation and postnatal life. The existence of 2 developmentally and morphologically distinct erythroid lineages, primitive (embryonic) and definitive (adult), was described for the mammalian embryo more than a century ago. Cells of the primitive erythroid lineage support the transition from rapidly growing embryo to fetus, whereas definitive erythrocytes function during the transition from fetal life to birth and continue to be crucial for a variety of normal physiologic processes. Over the past few years, it has become apparent that the ontogeny and maturation of these lineages are more complex than previously appreciated. In this review, we highlight some common and distinguishing features of the red blood cell lineages and summarize advances in our understanding of how these cells develop and differentiate throughout mammalian ontogeny.

Introduction

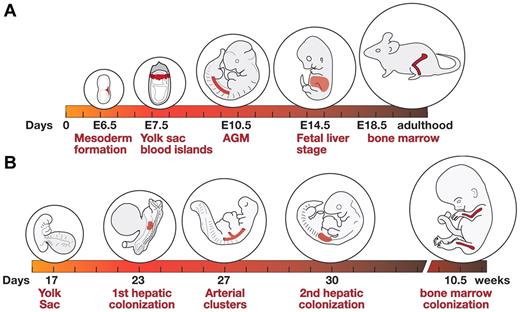

During embryonic development, hematopoiesis functions in the rapid production of large numbers of erythroid cells that support the growth and survival of the embryo/fetus and, later, in the generation of a pool of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) that persist throughout the life of the adult animal.1,2 Hematopoiesis in the developing vertebrate embryo occurs in multiple waves and in several different anatomic sites (Figure 1). The first wave occurs in the yolk sac in both mouse and humans3-5 and produces primarily primitive erythroid cells (EryP) as well as macrophages and megakaryocytes.3,6 The second wave also arises in the yolk sac but is “definitive,” composing erythroid, megakaryocyte, and several myeloid lineages.7,8 The third wave emerges from HSCs produced within the major arteries of the embryo, yolk sac, and placenta.1-3,9 HSCs home to and expand within the fetal liver and eventually seed the bone marrow.10,11 Definitive erythroid cells are produced continuously from HSCs in the bone marrow throughout postnatal life.1,2

Shifts in site of hematopoiesis during mouse and human development. (A) Hematopoietic development in the mouse. Formation of mesoderm during gastrulation (around E6.5), development of yolk sac blood islands (∼ E7.5), emergence of HSCs in the aorta-gonad-mesonephros region (E10.5; other sites such as large arteries and placenta not shown), active fetal liver hematopoiesis (E14.5), and hematopoiesis in the bone marrow of the late gestation fetus (E18.5) and adult animal. Active circulation begins at approximately E9.0.43 (B) Hematopoietic development in the human embryo. An embryo at yolk sac stage of hematopoiesis (day 17), at the time of the first hepatic colonization by HSCs (day 23), arterial cluster formation (day 27), second hepatic colonization (day 30), and bone marrow colonization (10.5 weeks). Active circulation begins at approximately day 21.3

Shifts in site of hematopoiesis during mouse and human development. (A) Hematopoietic development in the mouse. Formation of mesoderm during gastrulation (around E6.5), development of yolk sac blood islands (∼ E7.5), emergence of HSCs in the aorta-gonad-mesonephros region (E10.5; other sites such as large arteries and placenta not shown), active fetal liver hematopoiesis (E14.5), and hematopoiesis in the bone marrow of the late gestation fetus (E18.5) and adult animal. Active circulation begins at approximately E9.0.43 (B) Hematopoietic development in the human embryo. An embryo at yolk sac stage of hematopoiesis (day 17), at the time of the first hepatic colonization by HSCs (day 23), arterial cluster formation (day 27), second hepatic colonization (day 30), and bone marrow colonization (10.5 weeks). Active circulation begins at approximately day 21.3

Before the initiation of definitive (adult-type) hematopoiesis from multipotent stem cells in the fetal liver, the embryonic circulation is dominated by large, nucleated erythroid cells of the EryP lineage. Primitive erythropoiesis is transient: EryP progenitors are produced in the yolk sac of the embryo for only a brief period (∼ 2 days).7,12 Their terminally differentiated progeny persist in the circulation through the end of gestation and even for a while after birth.13 However, they are rapidly outnumbered by the rapidly expanding population of definitive erythroid cells (EryD) arising from the growing fetal liver.13,14

Failure in primitive erythropoiesis (as observed, for example, after targeted disruption of genes encoding the transcription factors Gata-1, Gata-2, Lmo2, or Scl) is uniformly associated with embryonic lethality.1,15 The importance of this lineage is underscored by the fact that primitive erythropoiesis is conserved among vertebrates.1,15

Emergence of primitive erythroid cells in the yolk sac

During gastrulation, a single epithelial cell layer (the epiblast) is transformed into the 3 germ layers of the embryo (ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm), and the basic body plan of the animal is established.16 In the mouse, gastrulation initiates around embryonic day (E) 6.5 (Figure 1A), when surface ectoderm cells undergo an epithelial-mesenchymal transition and become migratory, moving through the primitive streak and into the extraembryonic region of the embryo. There they form a mesodermal layer that lies directly adjacent to the visceral endoderm, in the early yolk sac.4 In the mouse, EryP are first detected at around E7.5, within “blood islands”5 (Figure 1A). They arise from mesodermal progenitors with restricted hematopoietic potential.

A role for yolk sac (visceral) endoderm in hematopoietic and vascular induction was suggested by classic studies in the chick embryo and was supported by the observation that embryoid bodies formed from Gata4-deficient embryonic stem (ES) cells lacked visceral endoderm and showed greatly reduced primitive erythropoiesis.17 Explant experiments with mouse embryos suggested that soluble signals from visceral endoderm activate hematopoiesis and vascular development during gastrulation17 and function, at least in part, through Indian hedgehog (Ihh), which may in turn regulate expression of BMP4 from the adjacent mesoderm.18,19 Recent coculture experiments have indicated that signals from primitive endoderm-derived extraembryonic endoderm cells20 can stimulate the expansion of EryP progenitors.21 Candidate-secreted factors identified on the basis of a microarray analysis include vascular endothelial growth factor and Ihh.21

Wnt/β-catenin signaling regulates specification of the EryP lineage from mesoderm in differentiating mouse ES cells22 in a process that requires inhibition of the Notch pathway.23 A microarray analysis of maturing primary mouse EryP isolated at distinct developmental stages indicated that a number of Wnt/β-catenin pathway genes are expressed in EryP progenitors and are rapidly down-regulated as the cells mature.12 That the Wnt pathway is active and functions autonomously in EryP progenitors was suggested by immunostaining for activated (stabilized) β-catenin and by fluorescence of a nuclear-GFP Wnt/β-catenin reporter in the blood islands of the yolk sac.12

The close spatial and temporal association between primitive erythropoiesis and vasculogenesis (the formation of blood vessels from angioblasts) in the yolk sac led to the concept of a common progenitor termed the “hemangioblast.”1,15 Hemangioblasts were thought to give rise to “blood islands,” clusters of EryP surrounded by endothelial cells within the mesodermal layer of the yolk sac.5 Experimental support for the hemangioblast came from studies of differentiating mouse and human ES cells24,25 and from mouse embryos.26 Although “blast colony”-forming cells (BL-CFCs) were hypothesized to be the in vitro equivalent of the hemangioblast,24 the majority of BL-CFC activity in the mouse embryo was found not in the yolk sac but in the posterior primitive streak.26 BL-CFCs are not strictly bipotential: in addition to primitive and definitive hematopoietic cell types,6,24 they can also give rise to smooth muscle in vitro.27

On the basis of lineage-tracing experiments, it was concluded that EryP and angioblasts in the yolk sac do not share a common progenitor.28 Analysis of mouse tetrachimeras expressing different fluorescent proteins has suggested that blood islands are polyclonal and, therefore, that hematopoietic and angioblastic lineage commitment in the yolk sac does not involve a 2-potential progenitor.29 However, it may be possible to reconcile these findings with the BL-CFC analyses from mouse embryos26 : the rare hemangioblasts in the posterior streak may produce more restricted progenitors (eg, megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitors, EryP progenitors, angioblasts) that then colonize the yolk sac. In a careful immunohistochemical analysis of the early mouse yolk sac,5 independent blood islands could not be identified. Instead, a “blood band” of CD41-positive hematopoietic progenitor cells was observed (∼ E7.75) to gradually circumscribe the proximal yolk sac.5 It was proposed that this blood band, containing primitive erythroid cells and more sparsely distributed endothelial cells, is later subdivided by layers of endothelial cells.5 Consistent with this idea, 2 waves of angioblast development have been identified in the yolk sac: one closely associated with and a second independent of hematopoiesis.30 Therefore, it remains unclear whether an equivalent of the hemangioblast exists in vivo.

Primitive erythropoiesis

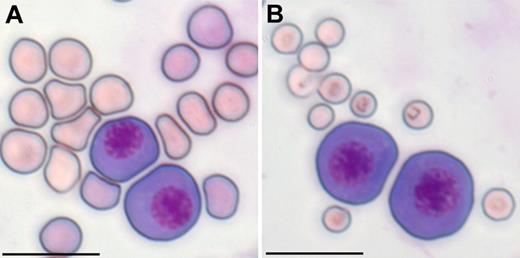

Embryonic and fetal erythropoiesis has been best studied in the mouse. Primitive and definitive erythroid cells are distinct lineages that arise from different populations of mesoderm (posterior and lateral plate, respectively) generated during gastrulation.4 Cells of the 2 erythroid lineages differ in a number of important characteristics. The “megaloblastic” EryP are much larger than either fetal liver or adult EryD (Figure 2), express distinct globin genes,34 and differ in their O2-carrying capacity and response to low oxygen tension.35 Whereas EryP form only in the yolk sac, progenitors for EryD are found both in the yolk sac and fetal liver.7,36 The primitive and definitive erythroid lineages also differ in their dependence on specific cytokines, transcription factors, and downstream regulatory pathways.

Primitive red blood cells are megaloblastic. EryP (E10.5) were mixed with (A) fetal (E17.5) or (B) maternal peripheral blood erythrocytes, cytospun, and stained with Giemsa as described by Fraser et al.13 Scale bar represents 20 μm.

Primitive red blood cells are megaloblastic. EryP (E10.5) were mixed with (A) fetal (E17.5) or (B) maternal peripheral blood erythrocytes, cytospun, and stained with Giemsa as described by Fraser et al.13 Scale bar represents 20 μm.

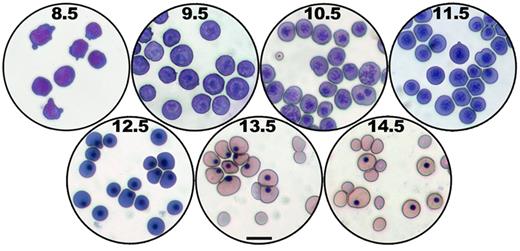

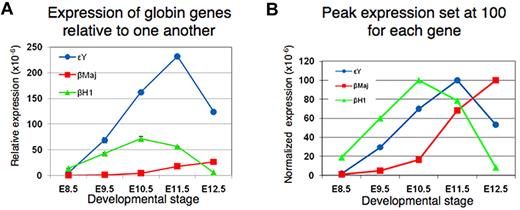

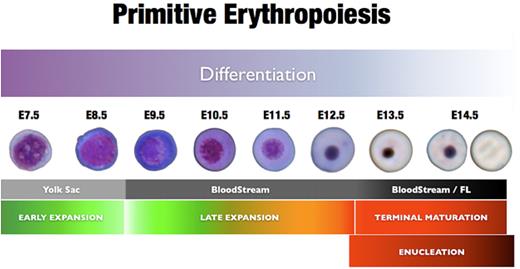

More than a century ago, it was observed that mammalian blood contains distinct nucleated and enucleated erythroid cells, leading to the conventional wisdom that a key distinguishing feature of primitive and definitive erythroid cells at all stages was the presence or absence of a nucleus.37 In contrast with EryD, which enucleate extravascularly in the fetal liver or adult bone marrow before entering the bloodstream, EryP were thought to retain their nuclei throughout their development. These large circulating cells were thought to represent a “primitive” form of erythropoiesis because, like the nucleated red cells of nonmammalian vertebrates, they formed in the yolk sac and were confined to embryonic stages of development. However, it is now clear that primitive erythroblasts in the mouse embryo are nucleated for only part of their life span, maturing and expelling their nuclei around midgestation.13,14 They then continue to circulate as enucleated cells until and perhaps, for a short time, past the time of birth.13 In addition to enucleation late in their maturation,13,14 the 2 lineages share a number of other features, including terminal differentiation from unipotential progenitors, progressive stages of maturation as nucleated erythroblasts,13,14,38 accumulation of hemoglobin, decrease in cell size, nuclear condensation, and regulation by erythroid transcription factors, such as GATA1 and EKLF/KLF1.12-14,37,39 The cytologic changes observed during primitive erythroid maturation are shown in Figure 3. EryP display “maturational” gene switching within the β-globin locus40 involving sequential changes in expression from βh1- to εY- (both embryonic) to adult βmaj- (β1) globin. It is evident from Figure 4A that εY-globin remains the predominant transcript throughout EryP development and that, even at late times, βmaj-globin expression remains low. The data are presented in a normalized form in Figure 4B, with peak expression set at 100 for each gene, to emphasize the sequential gene expression.

Cytologic changes during primitive erythroid maturation. Giemsa-stained cytospin preparations of FACS-sorted E8.5 EryP from dispersed ε-globin-H2B-GFP embryos12,42 or peripheral blood from wild-type embryos at E9.5 to E14.5.13 Panels E9.5 to 14.5 were taken from Fraser et al.13 Scale bar represents 20 μm.

Cytologic changes during primitive erythroid maturation. Giemsa-stained cytospin preparations of FACS-sorted E8.5 EryP from dispersed ε-globin-H2B-GFP embryos12,42 or peripheral blood from wild-type embryos at E9.5 to E14.5.13 Panels E9.5 to 14.5 were taken from Fraser et al.13 Scale bar represents 20 μm.

Maturational globin gene switching in developing primitive erythroid cells. “Maturational” globin gene switching40 refers to sequential changes in expression from βh1- to εY- (both embryonic) to adult βmaj- (β1) globin within the primitive erythroid lineage during its differentiation. (A) Relative expression is shown for the 3 β-like globin genes. εY-globin remains the predominant transcript throughout EryP development; even at late times, βmaj-globin expression remains low. (B) The data are presented in a normalized form, with peak expression set at 100 for each gene, to emphasize their sequential expression within maturing EryP from E8.5 to E12.5 (J.I., Z. He, M.H.B., unpublished data, February 2009).

Maturational globin gene switching in developing primitive erythroid cells. “Maturational” globin gene switching40 refers to sequential changes in expression from βh1- to εY- (both embryonic) to adult βmaj- (β1) globin within the primitive erythroid lineage during its differentiation. (A) Relative expression is shown for the 3 β-like globin genes. εY-globin remains the predominant transcript throughout EryP development; even at late times, βmaj-globin expression remains low. (B) The data are presented in a normalized form, with peak expression set at 100 for each gene, to emphasize their sequential expression within maturing EryP from E8.5 to E12.5 (J.I., Z. He, M.H.B., unpublished data, February 2009).

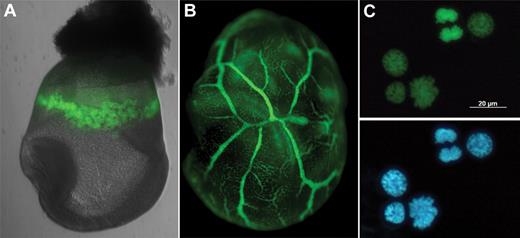

Primitive erythropoiesis has been difficult to study, in part because of the relative inaccessibility of the mammalian embryo and because EryP form at a time when the embryo is still extremely small. In addition, in the human embryo, the time during embryonic development at which blood islands first emerge (days 16 and 17, Figure 1B) is too early to be accessible from elective terminations of pregnancy.3 This difficulty underscores the value of the ES cell system for investigations into these early embryonic events.41 Past midgestation, maturing EryP and adult-type erythrocytes are present simultaneously within the circulation. The single monoclonal antibody that specifically recognizes mouse erythroid cells, Ter-119, binds to both EryP and EryD. To circumvent these problems, we have used human ε-globin regulatory elements to specifically drive expression of reporters, including lacZ,17,18 a pan-cellular green fluorescent protein (GFP),13,18 and a histone H2B-GFP fusion,42 within the mouse EryP compartment of transgenic mice (Figure 5). The fluorescent reporters have made it possible to isolate EryP progenitors12 and maturing EryP,13,42 to track EryP enucleation,13,42 and to generate a genome-wide transcriptome of this lineage at distinct stages of its development.12

Nuclear GFP reporter for EryP. (A) Histone H2B-GFP expression within the yolk sac “blood islands” of an E8.5 ε-globin-H2B-GFP transgenic embryo. (B) GFP(+) cells within the yolk sac vasculature of an E9.5 ε-globin-H2B-GFP transgenic embryo. (C) Nuclear expression of H2B-GFP fusion protein permits identification of mitotic figures and actively dividing cells. Blue represents 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. Embryos were imaged as in Isern et al.12,39

Nuclear GFP reporter for EryP. (A) Histone H2B-GFP expression within the yolk sac “blood islands” of an E8.5 ε-globin-H2B-GFP transgenic embryo. (B) GFP(+) cells within the yolk sac vasculature of an E9.5 ε-globin-H2B-GFP transgenic embryo. (C) Nuclear expression of H2B-GFP fusion protein permits identification of mitotic figures and actively dividing cells. Blue represents 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. Embryos were imaged as in Isern et al.12,39

Primitive erythroid progenitors

In the mouse, erythroid progenitors are found only in the yolk sac, but not in the embryo proper, between E7.25 and E9.0.7,12 Primitive erythropoiesis may involve a limited hierarchy of progenitors in which a bipotential megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitor gives rise to unipotential EryP progenitors. In the mouse embryo, the first megakaryocytes, identified by staining for surface GP1bβ, are found in the yolk sac at E9.5 and in the blood at E10.5, substantially later than primitive erythroblasts.6 It is not clear whether the apparent temporal difference in emergence of these 2 lineages reflects a limitation in this method of detection of megakaryocytes or a true kinetic difference in maturation of their progenitors. In any case, EryP are the first morphologically identifiable hematopoietic cells of the embryo.

The signals that initiate differentiation of EryP progenitors, apparently just as the cells begin to enter the bloodstream,7,43 are unknown. EryP progenitors were initially identified retrospectively by their ability to form red-pigmented colonies in cultures containing semisolid medium supplemented with erythropoietin44 and were termed EryP-CFC.7 The identification and isolation of these progenitors have presented challenges because of a lack of specific cell surface markers. Expression of CD31 (PECAM1), Tie-2, CD34, and VE-cadherin45 or low level expression of CD4146 has been used to enrich for EryP progenitors from E7.0 to E7.5 embryos, but these proteins are also expressed on endothelial and/or definitive hematopoietic progenitors.

Recently, it has been possible to isolate EryP progenitors prospectively from E7.5 to E8.5 embryos12 on the basis of an EryP-specific GFP reporter expressed in mice.42 In this line, expression of a nuclear histone H2B-GFP fusion protein is driven by a human embryonic ε-globin promoter and sequences from the β-globin locus control region42 (Figure 5). The fusion protein coats chromatin and remains detectable through all phases of the cell cycle (Figure 5C). Thus, it permits tagging and tracking of EryP nuclei and identification of mitotic cells and has proven to be a very useful model for studying embryonic erythropoiesis.12,39,42,47 GFP fluorescence (and endogenous expression of embryonic globin genes) was detected in mouse embryos as early as E7.512 ; therefore, transgene expression is activated toward the end of gastrulation, at the time when the first erythroid cells are specified from nascent mesoderm.28 At E7.5 and E8.5, a substantial proportion (∼ 15%-20% and 50%, respectively) of all cells in the embryo expressed GFP, indicating that significant resources are set aside by the developing embryo for this single lineage.12 EryP progenitor activity, evaluated by quantifying EryP-CFC, was found exclusively in the FACS-sorted GFP-positive population and expanded rapidly between E7.5 and E8.5.12 A subset of GFP-positive cells from E7.5 embryos expressed Flk1, c-kit, VE-cadherin, and Tie-2 proteins, all normally associated with endothelial cells.12 All progenitor activity was found in the fraction of GFP-positive cells that expressed c-kit, whereas Tie-2 expression provided a 4-fold enrichment of progenitors in the GFP-positive population.12 Although progenitor activity is lost once EryP begin to enter the bloodstream,43 circulating EryP do continue to divide until around E13.5 (N. Neriec, S.T.F., M.H.B., unpublished data, August 2006).37

Interestingly, a variety of cell adhesion proteins (Pecam1, CD44, and the integrins α4, α5, β1, and β3) are found on the surface of EryP progenitors.12 Genes encoding additional adhesion molecules as well as collagens are also expressed in these cells.12 Therefore, within the yolk sac, EryP may form tight associations with each other and/or with surrounding endothelial cells, as suggested by electron microscopy.48 Loss of adhesion proteins from the surface of EryP in the yolk sac, along with expression of metalloproteases, might help to untether the cells and facilitate their entry into the bloodstream.12

Transition from yolk sac to circulation stage EryP

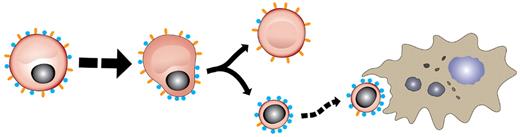

Shortly before midgestation in the mouse embryo, the circulatory systems of the embryo, yolk sac, and placenta connect. As the heart begins to beat (∼ E9.0), proerythroblastic EryP enter the circulation as a synchronous cohort of nucleated cells.43 Circulating EryP in rodents continue to mature within the bloodstream.13,14,38 They display a developmental progression from proerythroblast to orthochromatic erythroblast to reticulocyte that is characterized by loss of nucleoli (E9.5-E10.5), decreased cell diameter and cross-sectional area (E10.5-E11.5), condensation of nuclei to 20% of their original size (E10.5 onwards), expression of cell adhesion proteins (E12.5-E14.5),13,42 and enucleation to primitive reticulocytes (E12.5 onwards)13,14 (Figure 3). Thus, the maturation of primitive erythroblasts is stepwise and developmentally synchronized. EryP maturation is reflected in a progressive loss of CD71 and up-regulation of Ter-119 expression,13 analogous to that observed for fetal liver erythropoiesis.49 Proteins, such as β1 integrin and phosphatidylserine, are selectively partitioned onto the membrane surrounding the expelled nuclei of adult erythroid cells.50-52 In contrast, Ter-119 is partitioned to the reticulocyte membrane.51 Selective reorganization of surface proteins, such as Ter-119, CD71, and several integrins, occurs during enucleation of EryP as well.13,42 We have speculated that loss of adhesion proteins during maturation may facilitate entry of the reticulocyte into the circulation and that preferential coating of the extruded nucleus may facilitate its engulfment by macrophages.42 Figure 6 contains a summary of these changes.

Model for protein redistribution on surface of maturing erythroid cells. As EryP prepare to enucleate, redistribution of surface antigens (Ter119, orange; α4 and β1 integrins, blue) occurs such that the reticulocyte (enucleated erythroid cell) is decorated with Ter119 but displays little, if any, α4 and β1 integrin. Conversely, the extruded nucleus is preferentially coated with α4 and β1 integrins, perhaps facilitating engulfment by macrophages.42 Protein redistribution has been described for maturing adult erythroblasts as well.51

Model for protein redistribution on surface of maturing erythroid cells. As EryP prepare to enucleate, redistribution of surface antigens (Ter119, orange; α4 and β1 integrins, blue) occurs such that the reticulocyte (enucleated erythroid cell) is decorated with Ter119 but displays little, if any, α4 and β1 integrin. Conversely, the extruded nucleus is preferentially coated with α4 and β1 integrins, perhaps facilitating engulfment by macrophages.42 Protein redistribution has been described for maturing adult erythroblasts as well.51

The possibility that EryP enucleate was suggested by 2 reports from the 1970s describing enucleated megalocytic, hemoglobin-containing cells in the bloodstream.37 Four decades later, an antibody against a mouse embryonic β-like hemoglobin chain was used to demonstrate that EryP begin to undergo nuclear extrusion by E12.5.14 These observations were confirmed using a flow cytometric method in which nucleated and enucleated EryP could be distinguished and quantified in blood on the basis of binding of the cell-permeable DNA-binding fluorescent dye DRAQ5 and EryP-specific expression of GFP.13 Analysis of the kinetics of enucleation revealed a precipitous (50%) reduction in nucleated EryP between E13.5 and E14.5; this process was nearly complete by E15.5.13 However, the total number of GFP-positive EryP cells remained approximately the same from E12.5 to the end of gestation (R. Moore, S.T.F., M.H.B., unpublished data, October 2009).13 Thus, in contrast with the prevailing view that EryP survive for only 4 or 5 days and gradually disappear during gestation, perhaps by apoptosis,53,54 these experiments indicated that EryP are a stable population and that enucleation does not foreshadow their death.13 For at least 3 weeks after birth, approximately 0.5% of all cells in the bloodstream are GFP-positive EryP.13 It seems likely that the life span of a primitive erythrocyte is similar to that of an adult red blood cell and that EryP, like their adult counterparts, are eventually cleared by the spleen.

Niches for primitive erythroid maturation and enucleation

In contrast with definitive erythrocytes, which are released directly into the circulation from the fetal liver or adult bone marrow as enucleated cells, EryP enter the blood with their nuclei intact, at around E9.0, with the initiation of a strong heartbeat.43 EryP eventually extrude their nuclei, but, surprisingly, the first enucleated EryP are not detectable in the blood for at least 3 days (E12.5) after the cells have begun to circulate.13,14 This phase of primitive erythropoiesis is nearly complete by approximately E15.5.13,14 An explanation for this lag may be that EryP appear to collect and complete their maturation within the fetal liver,42,55 an organ that does not form until midgestation.

Detailed analysis of the surface phenotype of GFP-positive EryP revealed that integrins and other cell surface adhesion proteins are expressed on EryP beginning around E12.5, reflecting a previously unrecognized aspect of their maturation13 and suggesting that they may home to a fetal tissue, such as the liver, where they would continue to mature. Transgenic mouse lines expressing pancellular13 or nuclear42 (Figure 5) GFP were used to test this hypothesis. The fetal liver is the site of development of adult-type red blood cells, which mature within “erythroblastic islands” (EBIs).56 EBIs, which are also found in bone marrow and spleen, are 3-dimensional structures containing a central macrophage surrounded by erythroid cells at various stages of maturation.56 Cytoplasmic extensions from the macrophage make intimate contact with the erythroblasts, leading to the suggestion that the macrophages function as nurse cells and also engulf expelled erythroid nuclei.56

EryP appear to collect in the fetal liver and to integrate into EBIs, along with developing definitive erythroblasts.42 The EryP found in the fetal liver had uniformly and strongly up-regulated a range of adhesion molecules, including α4, α5, and β1 integrins and CD44, and showed greater adhesion to macrophages in reconstituted EBIs than did circulating EryP.42 The “rosettes” formed by these interactions were disrupted by a blocking antibody against VCAM-1, the macrophage receptor for α4β1 integrin42 and by peptide blocking of fibronectin binding by α4 and α5 integrins (J.I. and M.H.B., unpublished data, April 2008). Disruption of EryP-macrophage interactions using α4 integrin were reported by one group55 but was not observed by us, for blocking antibodies against either α4 or β1 integrin.42 Confocal microscopy and FACS analyses of fetal livers from the ε-globin–H2B-GFP (nuclear GFP) transgenic mice indicated that nuclei extruded by EryP, like those of adult red blood cells,52 undergo phagocytosis by macrophages.42 In both adult and embryonic lineages, nuclear extrusion occurs by budding off of the highly condensed nucleus surrounded by a rim of plasma membrane.55

The nuclear-GFP reporter made it possible to monitor EryP enucleation at high resolution using flow cytometry. Bright GFP-positive structures with very low granularity were FACS-purified from the bloodstream and fetal liver and displayed the morphology expected for expelled nuclei, with a surrounding remnant of cytoplasm and a cell membrane.42 Using antibodies against mouse embryonic β-hemoglobins to identify EryP, others have also found that these cells can interact with macrophages, which can engulf the expelled nuclei in vitro.55 The GFP fluorescent signal allowed us to sort and analyze the extruded nuclei, which were highly enriched for integrins, in contrast with the enucleated primitive reticulocytes that showed little or no expression of these proteins.42 Therefore, adhesion molecules are specifically redistributed onto the membrane surrounding the expelled nucleus, perhaps causing it to become more attractive for engulfment by fetal liver macrophages42 (Figure 6). Protein sorting has also been described for enucleating adult erythoblasts.51 The stages of primitive erythropoietic development are summarized in Figure 7.

Stages of primitive erythropoiesis. Summary of different phases of EryP development, from progenitor to bloodstream (where the cells continue to undergo limited proliferation) to terminal maturation and enucleation. The images of EryP at different stages were cropped from photographs of actual Giemsa-stained cells.

Stages of primitive erythropoiesis. Summary of different phases of EryP development, from progenitor to bloodstream (where the cells continue to undergo limited proliferation) to terminal maturation and enucleation. The images of EryP at different stages were cropped from photographs of actual Giemsa-stained cells.

Although the numbers of free GFP-positive EryP nuclei detected in the circulation were lower than in the fetal liver, suggesting that a small fraction briefly escape engulfment by macrophages and enter the bloodstream, it is also possible that some EryP enucleate while in circulation. The free nuclei presumably are phagocytosed later, when they circulate through the fetal liver or other tissues,42 possibly including the placenta, as reported for the human embryo.57 Human primitive erythroblasts also enucleate, but the site is apparently the placental villi rather than the fetal liver.57 Microscopic analysis suggests that the nuclei expelled by human EryP are engulfed by macrophages, although this finding remains to be confirmed more directly57 (eg, using FACS). Interestingly, macrophage progenitors are present in the human placenta before the onset of circulation.57 Whether enucleation of EryP also occurs in the mouse placenta is not known.

Collectively, these results indicate that one of the major roles of fetal liver macrophages is the engulfment and destruction of erythroid nuclei. Although a role for macrophages in definitive erythroid cell maturation is well accepted,56 several lines of evidence suggest that macrophages are not essential for their enucleation in vivo.58 Enhancement of EryP enucleation during coculture on fetal liver macrophages was detected in one study55 but not in another.42 Nevertheless, interactions with macrophages may facilitate other aspects of erythroid maturation. For example, erythroid progenitors expand and mature more efficiently in vitro in the presence of stromal cells,59 and definitive erythroblast proliferation is stimulated by coculture with macrophages.60

Emergence of definitive erythroid lineages in the yolk sac and fetal liver

The fetal liver provides a microenvironment(s) for the expansion and differentiation of definitive HSCs, from which definitive erythroid cells differentiate via a hierarchy of progenitors.1,2 For many years, the first definitive erythroid cells were thought to originate from HSCs that colonize the fetal liver.1,2,61 However, a second wave of hematopoiesis was found to emerge from the yolk sac at around E8.25 to E8.5; it produces cells of the definitive erythroid lineage, identified in vitro using an assay for erythroid burst-forming units, as well as megakaryocyte and myeloid lineages.6-8,62 The second wave of hematopoiesis also includes multipotential, highly proliferative progenitors (HPP-CFC) identified in vitro.62 HPP-CFC and more extensively self-renewing erythroid progenitors that expand in culture63 are both found in the yolk sac at about the same time of development. These progenitors are maintained in culture under different growth factor and cytokine conditions,62,63 however, and their lineage relationship in vivo (if any) is unclear. In addition, HPP-CFC lack HSC activity and are found in the yolk sac 12 to 24 hours earlier than the first newborn repopulating HSCs64 are detected (M. Yoder, personal oral communication, October 2011).

Recently, it has been demonstrated that erythropoiesis in the fetal liver begins before its colonization by HSCs.36 Early definitive erythroblasts were isolated by flow cytometry on the basis of expression of c-kit (which is not found on EryP at this stage of their development12,13 ) and shown to display a distinct and unique profile of endogenous mouse and transgenic human globin gene expression.36 Maturing definitive erythroblasts isolated from E9.5 yolk sac show the same pattern of β-globin gene expression as the early (E11.5) definitive fetal liver erythroblasts. This observation and several other lines of circumstantial evidence suggest that the first definitive erythroblasts in the fetal liver arise from yolk sac erythroid/myeloid progenitors,36 although this remains to be demonstrated directly. It has been proposed that erythroid/myeloid progenitor-derived definitive erythropoiesis bridges the transition between primitive and HSC-derived erythropoiesis.2,36 It is tempting to speculate that the first hepatic colonization described for the human fetus (Figure 1B) might correspond to the second wave of hematopoiesis identified in the mouse embryo.

Definitive HSCs arise in the mouse embryo in the para-aortic splanchnopleure (E7.5-E9.5), the aorta-gonad-mesonephros region (E10.5-E11.5), the major blood vessels, and in the placenta.1,2,9 The HSCs that form in these tissues do not differentiate there but seed the developing fetal liver, thymus, and bone marrow, presumably as niches form and acquire the ability to support HSC self-renewal.1,2,9 The final wave of definitive hematopoiesis produces all lineages, including B and T lymphoid potentials.1,2

Development of the hematopoietic system in humans is less well studied but is broadly similar to that of the mouse.3,9 In the human embryo, erythroid burst-forming unit activity is first detected at 7 to 8 weeks, after the second wave of colonization of the fetal liver by HSCs3 (Figure 1B). Fetal and adult human erythrocytes can be distinguished by their production of distinct forms of hemoglobin (hemoglobin F or A, respectively).34 The switch in expression of fetal to adult β-like globin genes begins at approximately 32 weeks and is completed after birth.34 In the human embryo, as in the mouse, HSCs have been identified in the aorta-gonad-mesonephros region, large vessels, and placenta.65

Growth factor requirements for erythropoiesis

Little is known about the growth factor requirements for primitive erythropoiesis in vivo. The hormone erythropoietin plays an essential role in definitive erythropoiesis, providing a key survival signal for late progenitors (colony-forming units-E).66 Mouse embryos deficient for the erythropoietin receptor have measurable but somewhat late defects in the proliferation and maturation of primitive erythroblasts but not progenitors, becoming evident only around E10.5 and later.67 Embryonic death from severe anemia occurs by E13.5, with a nearly complete ablation of definitive erythropoiesis.67,68 The differential effects of loss of erythropoietin receptor signaling in the 2 lineages suggests a role for additional cytokines in EryP development.37

Stem cell factor (or kit ligand) also has a differential effect on EryP and EryD in mouse. Stem cell factor receptor (c-kit) mutants die of severe anemia because of a failure in definitive erythropoiesis.69 Although c-kit is expressed on the surface of EryP progenitors,12,45 their proliferation, survival, and maturation are unaffected by exogenous stem cell factor in culture.12 EryP progenitors express another receptor tyrosine kinase receptor, Tie-2,12,45 but their growth was not consistently stimulated by addition of a recombinant Tie2 ligand, angiopoietin-1.12 It is possible that functions for c-kit and/or Tie-2 signaling could be unmasked by development of serum-free culture conditions for EryP progenitors.12

The TGF-β pathway has been implicated in embryonic erythroid development. On certain genetic backgrounds, embryos deficient for TGF-β1 die by midgestation from hematopoietic and vascular defects70 ; this phenotype is regulated by a genetic modifier.71 It is not known whether the hematopoietic defects observed70 reflect abnormalities in the formation and/or proliferation of EryP progenitors or their maturation. Targeted mutation of the Tgfbr1 receptor gene also results in embryonic lethality, but in this case it was concluded that the defect involved angiogenesis and that hematopoiesis was normal.72 However, the mutant embryos were clearly anemic and EryP progenitor assays were not performed.72 Deletion of Tgfbr2 also resulted in hematopoietic and vascular defects in the yolk sac.73 These embryos clearly had greatly reduced numbers of EryP in the vessels of sectioned tissue, but no further analysis was performed. Findings from our gene-expression profiling study prompted us to reevaluate the possibility of a role for TGF-β signaling in the primitive erythroid lineage. EryP progenitors express mRNAs for receptors (Tgfbr1 and Tgfbr3, Acvr2b) and downstream signaling components (eg, Smad3, Smad4, and Smad5) of these pathways; transcription of these genes begins to decrease by E8.5.12 To determine whether the TGF-β signaling pathway can modulate the expansion of EryP progenitors, we tested recombinant forms of the 3 Tgfbr1 ligands TGF-β1, TGF-β2, and TGF-β3 in clonogenic assays. TGF-β1 (but not TGF-β2 or TGF-β3) showed a dose-dependent effect on EryP progenitor activity in vitro: growth of EryP progenitors was inhibited at a low concentration and stimulated at higher concentrations of this cytokine.12 The TGF-β signaling pathway may function via an autocrine or paracrine mechanism, as both the receptor and its ligand, Tgfβ1, are transcribed in EryP.12 In contrast, TGF-β1 has been viewed as an inhibitor of definitive erythropoiesis in vitro, decreasing proliferation of progenitors and inducing their differentiation.74 A more detailed evaluation of the function of this pathway in EryP is warranted.

Fibroblast growth factor receptor-1 is required for hematopoietic development in differentiating mouse ES cells75 but whether the absence of the receptor affects primitive and/or definitive erythroid lineages was not defined. Sprouty (Spry) proteins antagonize signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases, such as fibroblast growth factors and epidermal growth factor.76 A recent study concluded that Spry1 negatively regulates primitive erythropoiesis in mouse embryos, but EryP progenitor assays were not performed77 and the cellular basis for the defect needs to be clarified.

Metabolic changes during EryP development

EryP must adapt to changes in oxygen and nutrient supplies during their maturation within successive microenvironments (yolk sac, circulation, and fetal liver) within the embryo.42 The expression profile of EryP is consistent with high glycolytic activity in progenitors, followed by a metabolic switch as a group of genes known to play crucial roles in glucose metabolism are rapidly down-regulated around the time when these cells begin to circulate.12 In culture, not only are EryP progenitor numbers increased under conditions of low oxygen but the colonies that form in methylcellulose are also larger, apparently because of increased EryP-CFC proliferation.12 EryP progenitors also display a signature characteristic of the “Warburg effect” associated with rapidly proliferating cells (eg, cancer cells) that catabolize glucose aerobically and produce high levels of lactate in the cytosol, rather than using the more energy efficient mitochondrial pathway.78,79 We propose that EryP switch from aerobic glycolysis to mitochondrial oxidation as they enter the circulation. The rapid proliferation of EryP progenitors and their cellular response to hypoxia are reminiscent of stress erythropoiesis in the fetus and adult.80,81 It is not known whether the aerobic glycolytic profile of EryP progenitors simply reflects the particular energy demands of these rapidly dividing cells or is a more unique feature of primitive erythropoiesis.12

Transcriptional regulation of erythropoiesis

The specification and differentiation of erythroid cells have been well studied for the definitive lineage and are regulated at transcriptional, posttranscriptional, and epigenetic levels. This subject has been extensively reviewed by others.1,82-85 In this section, we emphasize key points and insights from the recent literature. The zinc finger protein GATA1 was one of the first cell type-restricted transcription factors to be identified and cloned for any lineage.1 Since that time, a battery of additional erythroid regulators have been discovered; the reader is referred to excellent “primers” on core erythroid transcription factors (notably, GATA1, EKLF/KLF1, NFE2, and SCL) and cofactors (FOG1, CBP/p300, TRAP200, BRG1, and others).82-84

Genome-wide expression profiling revealed that transcription in maturing EryP is characterized by 2 discrete waves that correlate with key developmental hallmarks.12 GATA1 and EKLF are central players in both primitive and definitive erythropoiesis. GATA1 and GATA2 overlap in function in primitive erythropoiesis, as demonstrated by analysis of double-knockout embryos.86 EKLF was initially thought to function primarily, if not exclusively, in definitive erythropoiesis,87,88 although its expression had been detected in mouse embryos as early as E7.5.89 It was later appreciated that Eklf functions in primitive erythropoiesis as well.53,90 We were able to analyze the impact of loss of one or both alleles of Eklf during primitive erythropoiesis by crossing the ε-globin:H2B-GFP transgenic mouse42 onto an Eklf mutant background.88 Haploinsufficiency of Eklf had a profound effect on the surface phenotype of EryP but not EryD, suggesting that the differentiation of EryP may be more sensitive to gene dosage than that of EryD.39 Indeed, the levels of Eklf are approximately 3-fold lower in EryP than in EryD.91 However, fetal-to-adult globin gene switching is also sensitive to Eklf gene dosage91,92 : haploinsufficiency of EKLF in humans causes hereditary persistence of fetal hemoglobin.92

EryP and EryD differ in their requirements for a variety of other transcriptional regulators. For example, in contrast with fetal liver erythropoiesis, which is dependent on the function of the proto-oncogene c-Myb, the core binding factor Ruxn1, and the Kruppel-type zinc finger protein ZBP-89, primitive erythropoiesis is not.93-96 However, although it is not crucial for primitive erythropoiesis, Runx1 does function in the development of EryP.97 The ε-globin:H2B-GFP transgenic mouse42 should be useful in identifying functions for additional transcription factors that may not be essential in EryP. Conversely, lineage-specific ablation of genes in EryP will permit the identification of genes that are critical for primitive but not definitive erythropoiesis.

Both the primitive and definitive erythroid and megakaryocyte lineages share a common progenitor (megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitor).98 Eklf had been shown to play a dual role in definitive hematopoiesis by promoting erythropoiesis and suppressing megakaryopoiesis.98,99 We found that null mutation of Eklf resulted in a partial “identity crisis”39 within maturing EryP in the circulation, with up-regulation of a subset of megakaryocyte-related surface proteins, such as CD41 and Pecam-1/CD31, and transcription factor genes, such as Fli-1.39 Therefore, loss of Eklf in EryP causes a partial change in cellular identity.39 Additional observations12 suggest that Eklf not only regulates lineage divergence from the megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitor but also controls various aspects of EryP maturation.12 Findings such as these underscore the utility of the ε-globin–H2B-GFP transgenic mouse line42 for evaluating the effects of targeted mutations specifically in the primitive erythroid lineage.

It is now appreciated that not only the absolute and relative levels of these proteins but also their order of action is critical in the segregation of erythroid and megakaryocytic lineages as well as in their differentiation.1,84,100,101 For example, conditional deletion of Gata1 and Zfpm1 (which encodes FOG1) revealed that FOG1 and GATA1 function sequentially in the formation and lineage divergence of erythroid-megakaryocytic progenitors during definitive hematopoiesis.101 GATA1 and EKLF form large complexes with many other proteins to regulate the expression of erythroid-specific genes.102,103

ChIP-Seq, in which chromatin immunoprecipitation is coupled with high-throughput DNA sequencing, has made it possible to generate genome-wide maps of binding by transcription factors, such as GATA1, GATA2, and NF-E2,104,105 and thereby define the full repertoire of loci occupied by these factors. Advances in this technology have allowed the identification of much wider combinatorial interactions among transcription factors than was previously possible.102,103 Although detailed analysis of individual transcription factors has provided a wealth of information about their functions in erythroid cells, there has been increasing emphasis on their coordinated binding. It would be of interest to compare the transcription complexes that form at different stages of EryP development (Figure 4) with those found in differentiating EryD.

In conclusion, although erythropoiesis has traditionally been described as encompassing embryonic (primitive) and “adult-type” (definitive) phases, it now appears that there are not 2, but 3 distinct erythroid lineages, each with a unique pattern of β-globin gene expression.36 Thus, the erythroid burst-forming units that arise from HSCs in the fetal liver actually constitute a third wave of erythropoiesis. In addition, at least in the mouse, switching in globin gene expression during development reflects maturational switches within a single erythroid lineage36,40 (Figure 4) as well as lineage switching (Figure 1). The progenitors that produce EryP are the first hematopoietic cells of the embryo and are found in the yolk sac only briefly but terminally differentiated primitive erythrocytes are present in the circulation through the end of gestation and probably for a short time after birth13 (primitive erythropoiesis is summarized in Figure 7). The ontogeny of erythropoiesis is much more complex than previously appreciated. It will be important to take this complexity into consideration when interpreting observations made not only in the embryo/fetus but in cell culture systems, such as ES and iPS cells. Comparative studies of erythropoiesis at different stages of development, in different tissues within the same stage, and in different species will probably continue to lead to refinements in our understanding of the biology of the red blood cell lineage.

Some of the pathways involved in the maturation of EryP and EryD are probably conserved. Surprisingly little is known about how red blood cells enucleate, even in the adult. Similarly, the mechanisms underlying the redistribution of proteins on the surface of erythroid cells as they mature (Figure 6) have barely been explored. Comparisons between primitive and definitive erythropoiesis may provide useful insights into these processes, our understanding of which remains largely descriptive. Elucidation of the common as well as the distinguishing features of embryonic versus adult erythroid development will be a prerequisite for the directed differentiation of human stem or progenitor cells for therapeutic purposes and for the efficient production of pure populations of red blood cells for transfusion in patients. The study of red blood cells will probably continue to provide fascinating insights into fundamental questions in biology and information of considerable practical value.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (grants RO1 HL62248, DK52191, and EB02209), the Roche Foundation for Anemia Research (grant 9699367999, cycle X), and the New York State Department of Health (NYSTEM grant N08G-024, M.H.B.).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: M.H.B. created figures and wrote the paper; J.I. created figures; and S.T.F. wrote an initial draft of the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for J.I. is Cardiovascular Development and Repair Department, Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares, Madrid, Spain. The current affiliation for S.T.F. is Disciplines of Physiology, Anatomy and Histology, School of Medical Sciences, University of Sydney, Camperdown NSW, Australia.

Correspondence: Margaret H. Baron, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, Box 1079, 1468 Madison Ave, Annenberg 24-04E, New York, NY 10029-6574; e-mail: margaret.baron@mssm.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal