Abstract

Proinflammatory cytokines such as TNFα are elevated in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN), but their contribution to disease pathogenesis is unknown. Here we reveal a central role for TNFα in promoting clonal dominance of JAK2V617F expressing cells in MPN. We show that JAK2V617F kinase regulates TNFα expression in cell lines and primary MPN cells and TNFα expression is correlated with JAK2V617F allele burden. In clonogenic assays, normal controls show reduced colony formation in the presence of TNFα while colony formation by JAK2V617F-positive progenitor cells is resistant or stimulated by exposure to TNFα. Ectopic JAK2V617F expression confers TNFα resistance to normal murine progenitor cells and overcomes inherent TNFα hypersensitivity of Fanconi anemia complementation group C deficient progenitors. Lastly, absence of TNFα limits clonal expansion and attenuates disease in a murine model of JAK2V617F-positive MPN. Altogether our data are consistent with a model where JAK2V617F promotes clonal selection by conferring TNFα resistance to a preneoplastic TNFα sensitive cell, while simultaneously generating a TNFα-rich environment. Mutations that confer resistance to environmental stem cell stressors are a recognized mechanism of clonal selection and leukemogenesis in bone marrow failure syndromes and our data suggest that this mechanism is also critical to clonal selection in MPN.

Introduction

Many cases of Philadelphia chromosome-negative myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN) are characterized by an activating point mutation of JAK2 (JAK2V617F). It has been generally accepted that JAK2V617F-positive cells outpace normal hematopoietic cells as a result of constitutively active growth factor signaling1 ; however, failure of JAK2V617F to confer a significant competitive advantage over normal hematopoiesis in 2 independent knock-in MPN models2,3 suggests that additional factors may be required to promote expansion of JAK2V617F-positive cells in patients.

As MPN patients overproduce certain proinflammatory cytokines known to suppress normal hematopoiesis,4 it is conceivable that JAK2V617F may protect mutant stem cells and progenitors from the apoptotic cues induced by these cytokines.

In this context, we recently observed that TNFα levels are elevated in mice with retrovirally induced JAK2V617F MPN.5 The physiologic effects of TNFα are complex and cell type-dependent, ranging from stimulation of proliferation to induction of apoptosis.6 TNFα negatively regulates the expansion and self-renewal of pluripotent hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs)7,8 and has inhibitory effects on normal as well as some leukemic human hematopoietic progenitor cells.9-11

TNFα's involvement in the evolution of leukemia is not without precedent. Studies in Fanconi anemia (FA) have implicated TNFα hypersensitivity as a central mechanism of clonal evolution and progression to acute myeloid leukemia. In the FA Complementation Group C murine model (Fancc−/−) TNFα induces bone marrow failure12 and can promote the evolution of somatically mutated TNFα-resistant preleukemic stem cell clones.13 Taking into account TNFα's role in clonal evolution and that elevated TNFα levels are present in human MPN we hypothesized that JAK2V617F induces TNFα expression and simultaneously confers TNFα resistance to MPN progenitor cells.

Methods

Isolation and culture of primary cells

Blood mononuclear cells (MNCs) were obtained from peripheral blood samples of patients with polycythemia vera (PV) and essential thromobocythemia (ET), myelofibrosis (MF), or normal volunteers. CD34+ cells were obtained from bone marrow of normal, PV and ET patients or peripheral blood of MF patients. All patients gave their informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki to participate in the study, which was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU), Portland Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Cornell University, and Freiburg University.

Cell separation and human hematopoietic colony assays

Peripheral blood and bone marrow MNC were isolated by density gradient centrifugation using Ficoll (Nycomed). Lysis of residual red blood cells (RBCs) was accomplished with Ammonium Chloride Lysing (ACK) buffer. For colony formation assays using MNCs, cells were plated in triplicate in methylcellulose culture at a density of 1 × 105 cells/mL. For CD34+ colony formation assays MNCs were incubated with anti–human CD34 microbeads (Miltenyi) and column purification was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol. After confirmation of > 92% purity by flow cytometry using a FACS Aria II (BD Biosciences) cells were plated at a density of 4000 cells/mL (in triplicate) in Methocult H4320 (StemCell Technologies), supplemented with human erythropoietin (hEPO; Procrit, Amgen) at the concentration described in each figure, 10 ng/mL human IL-3 (hIL-3; Peprotech) and 50ng/mL human stem cell factor (hSCF; Peprotech) ± 1, 10 or 100 ng/mL human TNFα (R&D Systems). Plates were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 95% air mixture in a humidified incubator for 12 days. Hematopoietic colonies were scored by standard morphologic criteria using an inverted microscope.

Genotyping of hematopoietic colonies

Individual colonies were harvested at day 12 into 100 μL deionized water. Genotyping was performed by PCR followed by digestion with BsaXI (New England BioLabs) as previously described.14

TNFα ELISA

Peripheral blood was collected into EDTA and centrifuged for 15 minutes at 1000g within 30 minutes of collection. The resulting plasma was removed and stored at −80°C until quantification. TNFα ELISA was performed using Quantikine HS (R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Pharmacologic inhibitors of JAK2

RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, and qPCR

RNA was extracted by using the RNeasy mini kit (QIAGEN) with subsequent DNaseI digestion procedure according to the manufacturer's instructions. Samples were then either stored at −80°C or subsequent cDNA synthesis was performed using the SuperScript III First-Strand synthesis system for RT-PCR (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. qPCR was performed on an Opticon2 DNA Engine (MJ Research) using dual hybridization probes (Light Cycler 480 Probes Master; Roche). GAPDH was used as a reference gene using the human/murine GAPDH probe #9, the murine TNFα probe #49, and the human TNFα probe #29 (all from Universal Probe Library; Roche).

The following primer pairs were used: murine TNFα forward: 5′- TGCCTATGTCTCAGCCTCTTC-3′; murine TNFα reverse: 5′-GAGGCCATTTGGGAACTTCT-3′; murine GAPDH forward: 5′- AGCTTGTCATCAACG GGAAG-3′; murine GAPDH reverse: 5′-TTTGATGTTAGTGGGGTCTCG -3′; human TNFα forward; 5′- TCAGCCTCTTCTCCTTCCTG-3′; human TNFα reverse: 5′-TCAGCTTGAGGGTTTGCTAC-3′; human GAPDH forward: 5′-AACGGGAAGCTTGTCATCAA-3′; human GAPDH reverse: 5′-TGGACTCCACGACGTACTCA-3′. PCR cycling conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 minutes, followed by 50 cycles at 95°C for 10 seconds, 60°C for 50 seconds, and 72°C for 10 seconds, followed by a 10 minute terminal incubation at 72°C. Expression of target genes was measured in triplicates and was normalized to GAPDH.

TNF allele burden assay

The JAK2V617F real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) assay was developed using allele specific PCR (AS-PCR) primers14 for distinguishing wild-type from mutant alleles, and fluorescent resonance energy transfer (FRET) probes (with melting curves) for accurate and sensitive allele burden quantitation. The assay consisted of 2 separate qPCR reactions for the quantification of the wild-type and mutant alleles. For the mutant allele, the 12.5 μl reaction consists of 25 ng of genomic DNA, 1× LightCycler 480 Genotyping master mix (Roche), 200nM each of sensor (5′ – TTTTCCTTAGTCTTTCTTTGAAGCAGCAAGTA-FTIC) and anchor (5′ LC Red 640 –ATGAGCAAGCTTTCTCACAAGCATTTGGTTTTAA-Phosphate) probes, and 500nM each of forward (5′—GAACTATTTATGGACAACAGTCA) and reverse (5′ – GTTTTACTTACTCTCGTCTCCACAaAA) primers. For the wild-type allele, the 12.5 μL reaction consists of 25 ng of genomic DNA, 1× Genotyping master mix (Roche), 200nM each of sensor (5′ – CTTTCTCAGAGCATCTGTTTTTGTTTATATAGAAA -FTIC) and anchor (5′ LC Red 640 – TCAGTTTCAGGATCACAGCTAGGTGTCAG -Phosphate) probes, and 500nM each of forward (5′— GCATTTGGTTTTAAATTATGGAGTATaTG) and reverse (5′ – ATACTTAACTCCTGTTAAATTATAGTTTAC) primers. The probes were designed using LightCycler Probe Design Version 2 (Roche). The lower case letters in primers are intentional mismatch for better specification. Both assays have demonstrated no cross-reactivity with their counterpart cell lines (HEL expresses V617F vs CEM expresses wild-type). The V617F allele burden was measured by the Advanced Relative Quantification method using Second Derivative maximum method and PCR efficiency correction, and was reported as a ratio of the mutant allele divided by the sum of the wild-type and mutant alleles.

Expression vectors

The murine JAK2V617F-MSCV-IRES-GFP vector was kindly provided by Dr Ross Levine (Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY).

Bone marrow transplantation

TNFα knock-out mice (B6;129S-Tnftm1Gkl/J (stock 003008) and B6.129S-Tnftm1Gkl/J (stock 005540)) and their respective wild-type equivalents (B6129SF2/J and C57B/6J) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Retroviral infection and transplantation was performed as previously described.17 All mouse work was performed with approval from the OHSU and Portland VA Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Murine colony formation assays

Hematopoietic progenitors (lineagenegative, c-kit+ Sca-1−) were sorted using a FACS Aria II (BD Biosciences) from wild-type C57B/6J mice or Fancc−/− bone marrow and subjected to 2 rounds of spinoculation as previously described.17 GFP+ cells were then sorted and plated in triplicate at 500 cells/mL into M3230 methylcellulose (StemCell Technologies) supplemented with 50 ng/mL mSCF, 10 ng/mL mIL-3 (Peprotech), 5 U/mL hEPO (Amgen), ± mTNF (R&D Systems). Cells were enumerated at day 12, with visual confimation of GFP positivity for each colony.

Statistical analysis

Mean values ± SEM are shown unless otherwise stated. Student t test, Pearson correlation, or Mann-Whitney was used for comparisons (GraphPad Prism Version 5.0).

Results

MPN is associated with increased plasma levels of TNFα

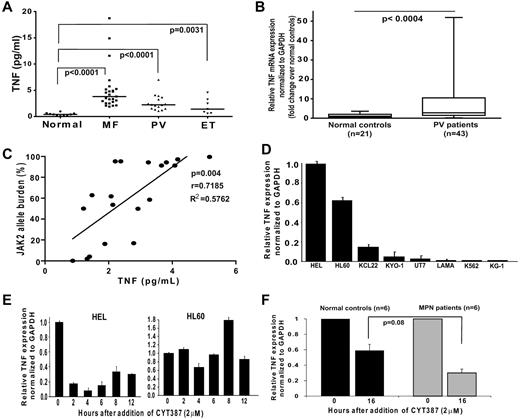

We have previously shown that TNFα concentrations are elevated in mice with experimentally induced JAK2V617F MPN compared with controls and reduced on treatment with CYT387, a JAK2 kinase inhibitor.5 In initial experiments we measured plasma TNFα in MPN patients and healthy controls (Figure 1A). Median TNF plasma concentrations in MF, PV and ET patients were 10, 5 and 4-fold higher than in controls (P < .0001, < .0001 and = .0031, respectively). Similarly we found 2-fold higher TNFα mRNA expression in peripheral blood white blood cells from an independent group of PV patients compared with normal controls (P < .0004; Figure 1B). These data show that TNFα is increased in MPN, but do not specifically delineate whether the increase in TNF is a direct consequence of JAK2V617F.

TNFα mRNA correlates with JAK2 kinase activity. (A) TNFα plasma concentration was evaluated in 48 MPN patients (16 PV, 7 ET, 25 MF) and 10 normal controls. Each data point represents a patient. Median TNFα concentration is shown as a bar. Detailed patient information including JAK2V617F status is provided in supplemental Table 1 (available on the Blood Web site, see the Supplemental Materials link at the online article). (B) qRT-PCR analysis of median TNFα mRNA expression of Peripheral blood leukocytes from 43 PV patients and 21 normal controls. Median TNFα expression in cells from normal controls was normalized to 1. (C) Correlation between JAK2V617F allele burden and TNF plasma concentration. Allele burden was determined in 20 JAK2V617F-positive patients by real-time quanitative PCR and correlated with TNF plasma concentration. (D) TNFα mRNA expression was analyzed by qRT-PCR in human hematopoietic cell lines and normalized to GAPDH. The TNFα expression in HEL cells was arbitrarily set to 1 and results for the other lines are shown in comparison. (E-F) TNFα mRNA expression after pharmacologic inhibition of JAK2, (E) HEL (left) and HL60 (right) cells treated with JAK2 inhibitor CYT387, (F) primary human blood MNCs treated with CYT387.

TNFα mRNA correlates with JAK2 kinase activity. (A) TNFα plasma concentration was evaluated in 48 MPN patients (16 PV, 7 ET, 25 MF) and 10 normal controls. Each data point represents a patient. Median TNFα concentration is shown as a bar. Detailed patient information including JAK2V617F status is provided in supplemental Table 1 (available on the Blood Web site, see the Supplemental Materials link at the online article). (B) qRT-PCR analysis of median TNFα mRNA expression of Peripheral blood leukocytes from 43 PV patients and 21 normal controls. Median TNFα expression in cells from normal controls was normalized to 1. (C) Correlation between JAK2V617F allele burden and TNF plasma concentration. Allele burden was determined in 20 JAK2V617F-positive patients by real-time quanitative PCR and correlated with TNF plasma concentration. (D) TNFα mRNA expression was analyzed by qRT-PCR in human hematopoietic cell lines and normalized to GAPDH. The TNFα expression in HEL cells was arbitrarily set to 1 and results for the other lines are shown in comparison. (E-F) TNFα mRNA expression after pharmacologic inhibition of JAK2, (E) HEL (left) and HL60 (right) cells treated with JAK2 inhibitor CYT387, (F) primary human blood MNCs treated with CYT387.

JAK2V617F allele burden and kinase activity correlate with expression of TNF

To identify a potential correlation between JAK2V617F and TNFα expression, we quantified JAK2V617F allele burden in 20 JAK2V617F-positive patients included in the TNFα plasma concentration analysis (Figure 1C). TNFα plasma concentration was found to correlate with JAK2V617F allele burden (Pearson r = 0.7185, R2 = 0.5762, P = .004). Consistent with the observed correlation between JAK2V617F and TNFα expression in primary human samples, splenocytes from a murine transduction/transplantation model of JAK2V617F MPN express increased levels of TNFα mRNA at baseline and produce exaggerated amounts of TNFα in response to LPS (supplemental Figure 1). To further validate the association between JAK2V617F and TNFα expression we compared TNFα mRNA in human hematopoietic cell lines either with or without the JAK2V617F mutation (Figure 1D). TNFα mRNA levels in HEL cells (homozygous for JAK2V617F and containing multiple copies of the gene) were elevated compared with all evaluated JAK2WT lines, supporting the notion that TNFα expression is positively regulated by JAK2V617F. To confirm that TNFα expression is regulated by JAK2 kinase activity, we treated TNF expressing cell lines with the JAK2 inhibitors CYT3875,15 (Figure 1E) or TG10120916 (supplemental Figure 2) and observed a time-dependent reduction of TNFα in the JAK2V617F-positive HEL cells, while CYT387 did not decrease TNFα mRNA expression in JAK2WT HL60 cells.18 JAK2 inhibition decreased TNFα mRNA in both MPN and normal blood MNC, although the effect was more pronounced in MPN samples (Figure 1F). These data show that JAK2V617F regulates TNFα expression in primary cells and JAK2V617F cell lines and accentuates physiologic JAK2-mediated TNF expression.

Differential effects of TNF on MPN and normal hematopoietic progenitor cells

TNFα levels are high in MPN patients yet JAK2V617F-positive cells exhibit dramatic expansion in this environment. Therefore to assess possible differential effects of TNFα on normal versus MPN progenitor cells we performed clonogenic assays on MNC in the presence of graded concentrations of EPO and TNFα (Figure 2A). Low TNFα concentrations (1ng/mL) increased BFU-E formation by MPN cells, but reduced BFU-E formation by normal MNC. Intermediate and high TNFα concentrations (10 and 100 ng/mL) decreased BFU-E and CFU-GM formation in both MPN and normal samples, but colony survival was consistently lower in normal controls. To minimize potential effects mediated through bystander cells within the MNC population we also assayed CD34+ cells (Figure 2B). In normal controls, 10 ng/mL TNFα suppressed BFU-E and CFU-GM colony formation by > 50%. In striking contrast, CFU-GM colony formation by MPN CD34+ progenitors was paradoxically enhanced by TNFα (P < .0001), and BFU-E formation was relatively resistant to TNFα (P = .08). These findings suggest that the differential response to TNFα may contribute to MPN pathogenesis by conferring a selective growth advantage to JAK2V617F-positive MPN cells in the TNFα rich environment of MPN patients.

MPN mononuclear cells and CD34+ cells are resistant to suppression of colony formation by TNFα. (A) Effect of TNFα on colony formation by progenitor cells from MNC. MNC from MPN patients (n = 14) and normal controls (n = 5) were plated in methylcellulose media supplemented with SCF, IL-3, with 5 U/mL (left) or 0.5 U/mL (right) EPO and graded concentrations of TNFα (in triplicate). Colonies were enumerated at day 12. Colony formation in 0 ng/mL TNFα is normalized to 100%. (B) Effect of TNFα on colony formation from CD34+ cells. CD34+ cells from MPN (n = 16 for 10 ng/mL TNFα, n = 3 for 1 ng/mL TNFα) and normal controls (n = 6 for 10 ng/mL TNFα, n = 3 for 1 ng/mL TNFα) were plated in methylcellulose media supplemented with SCF, IL-3 and 5 U/mL EPO, with graded concentrations of TNFα (in triplicate).

MPN mononuclear cells and CD34+ cells are resistant to suppression of colony formation by TNFα. (A) Effect of TNFα on colony formation by progenitor cells from MNC. MNC from MPN patients (n = 14) and normal controls (n = 5) were plated in methylcellulose media supplemented with SCF, IL-3, with 5 U/mL (left) or 0.5 U/mL (right) EPO and graded concentrations of TNFα (in triplicate). Colonies were enumerated at day 12. Colony formation in 0 ng/mL TNFα is normalized to 100%. (B) Effect of TNFα on colony formation from CD34+ cells. CD34+ cells from MPN (n = 16 for 10 ng/mL TNFα, n = 3 for 1 ng/mL TNFα) and normal controls (n = 6 for 10 ng/mL TNFα, n = 3 for 1 ng/mL TNFα) were plated in methylcellulose media supplemented with SCF, IL-3 and 5 U/mL EPO, with graded concentrations of TNFα (in triplicate).

To test whether TNFα favors growth of JAK2V617F colonies in individual MPN patients, we genotyped individual colonies grown with and without 10 ng/mL TNFα. TNFα consistently selected for JAK2V617F colonies and in some cases completely eliminated JAK2WT colonies (Figure 3). This effect was noted both in BFU-E and CFU-GM (supplemental Figure 3), demonstrating that JAK2V617F clones enjoy a selective advantage in the presence of TNFα.

TNF selects for JAK2V617F+ colony formation. Percentage of JAK2V617F mutant colonies in the absence or presence of TNFα. Colonies were plucked from (A) 6 MNC starting material and (B) 6 CD34+ starting material from plates with 0 ng/mL and 10 ng/mL TNFα (at least 30 individual colonies per condition) and JAK2 mutational status was determined. Panels A and B represent different patients and are numbered arbitrarily. Mutational analysis of separated CFU-GM and BFU-E from these patients is provided in supplemental Figure 3.

TNF selects for JAK2V617F+ colony formation. Percentage of JAK2V617F mutant colonies in the absence or presence of TNFα. Colonies were plucked from (A) 6 MNC starting material and (B) 6 CD34+ starting material from plates with 0 ng/mL and 10 ng/mL TNFα (at least 30 individual colonies per condition) and JAK2 mutational status was determined. Panels A and B represent different patients and are numbered arbitrarily. Mutational analysis of separated CFU-GM and BFU-E from these patients is provided in supplemental Figure 3.

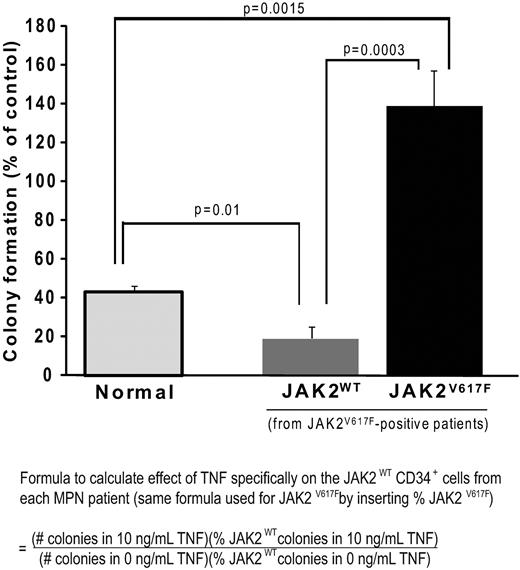

The preneoplastic CD34+ cell compartment of MPN patients is hypersensitive to TNF

We used the colony formation and genotyping data to separately calculate the effect of TNFα specifically on the preneoplastic (JAK2WT) and neoplastic (JAK2V617F) CD34+ compartment of individual JAK2V617F-positive patients. JAK2WT preneoplastic progenitors from JAK2V617F-positive MPN patients were much more sensitive to TNFα than normal controls (82 ± 23% vs 57 ± 10% reduction, P = .01; Figure 4), demonstrating that JAK2WT progenitor cells from JAK2V617F-positive MPN patients are intrinsically hypersensitive to TNFα.

Preneoplastic (JAK2WT) CD34+ cells from JAK2V617F-positive MPN patients are hypersensitive to TNFα. The genotyping data in Figure 3 was used to calculate the effect specifically on the JAK2WT or JAK2V617F CD34+ compartment of JAK2V617F+ patients. CFU-GM and BFU-E colony numbers were combined for analysis.

Preneoplastic (JAK2WT) CD34+ cells from JAK2V617F-positive MPN patients are hypersensitive to TNFα. The genotyping data in Figure 3 was used to calculate the effect specifically on the JAK2WT or JAK2V617F CD34+ compartment of JAK2V617F+ patients. CFU-GM and BFU-E colony numbers were combined for analysis.

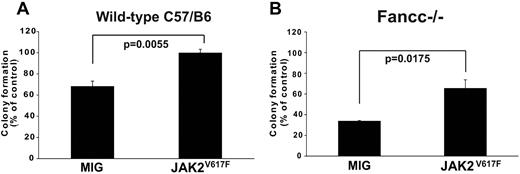

Ectopic expression of JAK2V617F protects murine hematopoietic progenitors from TNFα

To formally determine whether JAK2V617F expression is sufficient to confer TNFα-resistance we expressed JAK2V617F or empty vector in normal hematopoietic progenitor cells (lineageneg c-kit+ Sca-1−), and assessed colony formation in the presence of TNFα. JAK2V617F induced TNFα resistance (Figure 5A). The protective effect of ectopically expressed JAK2V617F was confirmed in TNFα-hypersensitive Fancc−/− progenitor cells (Figure 5B), which are intrinsically hypersensitive to TNF.19 These results show that JAK2V617F imparts TNFα-resistance to normal hematopoietic progenitors as well as progenitors with intrinsic TNFα hypersensitivity, suggesting that TNFα produced by MPN cells promotes their expansion at the expense of nonneoplastic hematopoiesis.

Ectopic expression of JAK2V617F attenuates TNFα-mediated suppression of myeloid colony formation. JAK2V617F or empty MIG vector was retrovirally expressed in hematopoietic progenitors (lineageneg c-kit+ Sca-1−) from the bone marrow of (A) wild-type and (B) Fancc−/− C57B/6J mice. Transduced (GFP+) cells were plated in methycellulose supplemented with 50 ng/mL mSCF, 10 ng/mL mIL-3 and 3 U/mL hEPO, either with or without TNFα (20 ng/mL for wild-type 10 ng/mL for Fancc−/−). Colony number was enumerated at day 12, with colony formation in conditions without TNFα set to 100%.

Ectopic expression of JAK2V617F attenuates TNFα-mediated suppression of myeloid colony formation. JAK2V617F or empty MIG vector was retrovirally expressed in hematopoietic progenitors (lineageneg c-kit+ Sca-1−) from the bone marrow of (A) wild-type and (B) Fancc−/− C57B/6J mice. Transduced (GFP+) cells were plated in methycellulose supplemented with 50 ng/mL mSCF, 10 ng/mL mIL-3 and 3 U/mL hEPO, either with or without TNFα (20 ng/mL for wild-type 10 ng/mL for Fancc−/−). Colony number was enumerated at day 12, with colony formation in conditions without TNFα set to 100%.

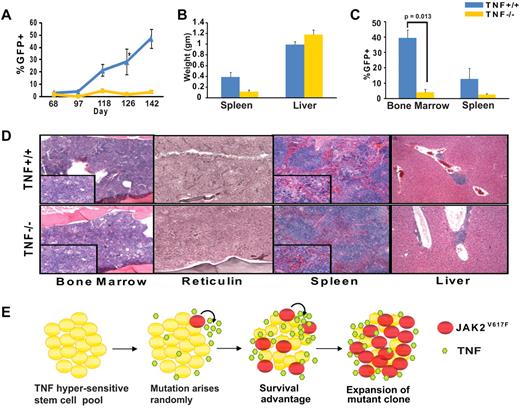

TNFα facilitates expansion of JAK2V617F cells in a murine transplantation model of MPN

To determine to which degree disease initiation and marrow harvested from 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) treated TNFα−/− and TNFα+/+ mice was infected with JAK2V617F-GFP retrovirus, and equal numbers of GFP+ cells were injected into lethally irradiated syngeneic recipients (whole bone marrow cells containing a total of 10 000 GFP+ per mouse, supplemental Figure 4). By day 48 mildly elevated white blood cell counts were evident in both groups (supplemental Figure 5). However, GFP+ cells in the peripheral blood as an indicator of disease burden steadily increased in the TNFα+/+, but not the TNFα−/− group (Figure 6A). The decreased proportion of GFP+ cells in the TNFα−/− mice was not because of an intrinsic long-term engraftment defect of TNFα−/− mice (supplemental Figure 6) nor to a decreased proportion of lineageneg c-kit+ Sca-1+ (LKS) cells in the inoculum (supplemental Table 2). This suggests that the presence of TNFα provides JAK2V617F-positive cells with a competitive advantage over their JAK2WT counterparts, thereby promoting their expansion. Consistent with this the TNFα−/− group showed significantly reduced splenomegaly and a lower proportion of GFP+ cells in the spleen and bone marrow (Figure 6B-C). In comparison with the TNFα+/+ group, the bone marrow of the TNFα−/− group demonstrated residual tri-lineage hematopoiesis and fewer atypical megakaryocytes; in spleen and liver MPN infiltrates and reticulin fibrosis were much less pronounced (Figure 6D). To confirm that attenuated disease in the absence of TNFα was not a strain-specific phenomenon we performed identical transplantation experiments in a mixed C57B/6 background (B6;129S-Tnftm1Gkl/J), with very similar results (supplemental Figure 7).

TNFα is not required for development of MPN but promotes expansion of JAK2V617F cells in a murine transplantation model. Bone marrow from 5-FU treated TNFα+/+ (C57B/6) or TNFα−/− (B6.129S-Tnftm1Gkl/J) mice was infected with JAK2V617F retrovirus by spinoculation and injected into syngeneic lethally irradiated hosts (n = 5 for each group). (A) Percentage of GFP+ cells in peripheral blood (B) spleen and liver weights at time of sacrifice, (C) percentages of GFP+ cells in bone marrow and spleen at time of sacrifice, and (D) H&E-stained histologic sections of representative TNFα+/+ and TNFα−/− bone marrow, spleen, and liver. Large panels represent 10× magnification, panel inserts represent 40× magnification of the same area. Images were captured with a Leica DC300 camera running IM50 Image Manager Version 5 software. (E) Model of TNFα-induced JAK2V617F clonal evolution in MPN. In a TNFα-sensitive stem cell pool JAK2V617F induced TNF resistance provides a strong selective advantage, allowing for the expansion of the mutant clone and development of clinical disease. Maintenance of a high TNFα environment by JAK2V617F cells further enhances the selective advantage for the JAK2V617F clone.

TNFα is not required for development of MPN but promotes expansion of JAK2V617F cells in a murine transplantation model. Bone marrow from 5-FU treated TNFα+/+ (C57B/6) or TNFα−/− (B6.129S-Tnftm1Gkl/J) mice was infected with JAK2V617F retrovirus by spinoculation and injected into syngeneic lethally irradiated hosts (n = 5 for each group). (A) Percentage of GFP+ cells in peripheral blood (B) spleen and liver weights at time of sacrifice, (C) percentages of GFP+ cells in bone marrow and spleen at time of sacrifice, and (D) H&E-stained histologic sections of representative TNFα+/+ and TNFα−/− bone marrow, spleen, and liver. Large panels represent 10× magnification, panel inserts represent 40× magnification of the same area. Images were captured with a Leica DC300 camera running IM50 Image Manager Version 5 software. (E) Model of TNFα-induced JAK2V617F clonal evolution in MPN. In a TNFα-sensitive stem cell pool JAK2V617F induced TNF resistance provides a strong selective advantage, allowing for the expansion of the mutant clone and development of clinical disease. Maintenance of a high TNFα environment by JAK2V617F cells further enhances the selective advantage for the JAK2V617F clone.

Discussion

Here we identify TNFα, a negative regulator of hematopoiesis, as a central mediator of clonal expansion in MPN. JAK2V617F expresssion skews the balance in favor of the JAK2V617F clone by up-regulating TNFα expression while at the same time conferring TNFα resistance to JAK2V617F-positive progenitor cells or even in the case of myeloid cells the paradoxical capacity to respond to TNFα with increased proliferation.

We show that JAK2V617F activity is positively correlated with expression of TNFα mRNA, suggesting that JAK2V617F directly up-regulates TNFα mRNA. In MPN patients the JAK2V617F allele burden is positivelycorrelated with TNF expression. It should be noted however that JAK2V617F-negative MPN patients also have increased plasma TNF concentrations (supplemental Table 1), suggesting that that these patients have genetic alterations that lead to JAK2 activation and phenocopy JAK2V617F in their ability to overproduce TNF. Examples include MPL and LNK mutations.20,21 The correlation between JAK2V617F and TNF expression is further supported by cell line data, which show that HEL cells homozygous for JAK2V617F have the highest TNF expression and that only in this line TNF is under the control of JAK2 kinase activity, as suggested by pharmacologic inhibition of kinase with 2 different inhibitors. Furthermore, treatment of primary human MNC with JAK2 inhibitors leads to a rapid and sustained down-regulation of TNF expression. While we cannot rule out that the small molecule inhibitors used in our studies regulate TNF by targeting kinases other than JAK2, they strongly suggest that TNF production in MPN is under the control of JAK2. The consequence is a high TNFα environment that perturbs physiologic TNFα regulation of hematopoiesis.

The second crucial effect of JAK2V617F on TNFα regulation of hematopoiesis is that the mutant confers resistance to TNFα. We provide several lines of evidence for this. Firstly, overall colony growth from MNC isolated from MPN patients was more resistant to TNFα compared with normal MNC. The differential TNFα effect was even more pronounced in CD34+ cells, where CFU-GM colony formation in the presence of 10 ng/mL of TNFα was reduced to 50% in normal controls, but enhanced to 125% in MPN samples. These data are further supported by our observation that ectopic expression of JAK2V617F confers TNFα resistance to normal as well as Fancc−/− progenitor cells. Thirdly, the absence of TNFα attenuated retrovirally induced murine MPN, evidenced by the failure of JAK2V617F cells (as measured by GFP+) to expand in the peripheral blood, spleen, and bone marrow. Reduced splenomegaly and less extensive involvement of the spleen with atypical megakaryocytes in the TNFα−/− group corroborated disease attenuation in the absence of TNFα. Altogether these data suggest that while MPN is not completely dependent on TNFá, JAK2V617F cells expand much more robustly in the presence of TNFα.

The implication of TNFα as an important driver of hematologic malignancies has a precedent in the bone marrow failure syndrome FA. FA patients are hypersensitive to and have elevated levels of TNFα, which promotes clonal evolution and leukemogenesis.22-25 The combination of genetic instability and cytokine hypersensitivity creates an environment that supports the selection of leukemic over nonleukemic stem cells.26,27 Malignant clones that arise are not only TNFα-resistant, but give rise to progeny that over-produce TNFα, further augmenting the selective pressure for expansion of the malignant clone over the hypersensitive parental stem cell pool. Here we provide evidence that a similar paradigm applies to MPN pathogenesis, in which TNFα suppresses the preneoplastic pool, while JAK2V617F expressing cells are protected from or even stimulated by TNFα (model depicted in Figure 6E). The similarities extend to another feature of FA, the TNF hypersensitivity of the preneoplastic stem cell pool. Our observations suggest subtle defects in JAK2WT stem cells of MPN patients render them hypersensitive to TNFα even before the evolution of JAK2V617F clones. This notion of an intrinsic defect in preneoplastic JAK2WT MPN cells is consistent with the decreased CFU-GM formation of progenitor cells from healthy individuals with the MPN predisposing 46/1 haplotype of JAK2 compared with controls without the 46/1 haplotype.28

If future studies confirm hypersensitivity to TNFα as a phenotype that antedates clonal evolution in MPN, knowledge of the underlying causes could help to develop rational risk assessment tools and prevention strategies for MPN. In addition, antagonizing TNFα may abrogate the growth advantage of MPN cells and induce clinical responses.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant HL082978-01 (M.W.D.), National Institutes of Health grants HL082978-01 (M.W.D.) and CA04963920A2 (M.W.D.), the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society grant 7036-01 (B.J.D. and M.W.D.), and the William & Judy Higgins Family Trust of the Cancer Research and Treatment Fund. K.J.A. is an Erwin Schroedinger Fellow of the Austrian Science Fund, grant J2758-B12. A.G.F. is supported by a NRSA T32 Molecular Hematology Training Grant and is the recipient of an Amgen Oncology Fellow Award. M.W.D. is a Scholar in Clinical Research of the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: A.G.F. and K.J.D. designed and performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; S.B.L. performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; F.Y., R.P., T.G.B., C.L.P., K.B.V., D.H.L., and M.M.L. performed experiments; S.D. performed experiments and analyzed data; H.L.P. and R.T.S. provided samples and reviewed the manuscript; A.A., T.O., B.J.D., and G.C.B. reviewed the manuscript; and M.W.D. designed experiments and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Michael W. Deininger, Division of Hematology and Hematologic Malignancies, University of Utah Huntsman Cancer Institute, 2000 Circle of Hope, Rm 4280, Salt Lake City, UT 84112-5550; e-mail: michael.deininger@hci.edu; or Angela G. Fleischman, Division of Hematology and Medical Oncology, Oregon Health & Science University Knight Cancer Institute, 3181 SW Sam Jackson Park Rd, Mail Code L592, Portland, OR 97239; e-mail: fleischm@ohsu.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal