Abstract

Monocytes are a heterogeneous cell population with subset-specific functions and phenotypes. The differential expression of CD14 and CD16 distinguishes classical CD14++CD16−, intermediate CD14++CD16+, and nonclassical CD14+CD16++ monocytes. Current knowledge on human monocyte heterogeneity is still incomplete: while it is increasingly acknowledged that CD14++CD16+ monocytes are of outstanding significance in 2 global health issues, namely HIV-1 infection and atherosclerosis, CD14++CD16+ monocytes remain the most poorly characterized subset so far. We therefore developed a method to purify the 3 monocyte subsets from human blood and analyzed their transcriptomes using SuperSAGE in combination with high-throughput sequencing. Analysis of 5 487 603 tags revealed unique identifiers of CD14++CD16+ monocytes, delineating these cells from the 2 other monocyte subsets. Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis suggests diverse immunologic functions, linking CD14++CD16+ monocytes to Ag processing and presentation (eg, CD74, HLA-DR, IFI30, CTSB), to inflammation and monocyte activation (eg, TGFB1, AIF1, PTPN6), and to angiogenesis (eg, TIE2, CD105). In conclusion, we provide genetic evidence for a distinct role of CD14++CD16+ monocytes in human immunity. After CD14++CD16+ monocytes have earlier been discussed as a potential therapeutic target in inflammatory diseases, we are hopeful that our data will spur further research in the field of monocyte heterogeneity.

Introduction

Monocytes are cornerstones of the immune system linking innate and adaptive immunity and are critical drivers in many inflammatory diseases. They are known to originate from a common myeloid precursor in the BM and give rise to tissue macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs).1,2

As diverse as monocyte function is their immunophenotype. Based on the differential expression of the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) receptor CD14 and the FcγIIIR CD16, 2 subpopulations were initially defined (CD14++CD16− monocytes and CD16-positive monocytes).3

However, considerable heterogeneity within the minor CD16-positive monocyte population does exist, which had been neglected until 2003, when Ancuta et al reported that CD16-positive monocytes can be further subdivided into phenotypically distinct CD14++CD16+ and CD14+CD16++ cells.4

The recently updated classification of monocyte heterogeneity follows this differentiation of CD16-positive monocytes into CD14++CD16+ and CD14+CD16++ monocytes and acknowledges the existence of 3 monocyte subsets, that is, classical monocytes (CD14++CD16−), intermediate monocytes (CD14++CD16+), and nonclassical monocytes (CD14+CD16++).5

As reviewed recently, the intermediate monocyte subset remains poorly characterized because of the fact that most clinical and experimental studies either ignored these cells, or analyzed intermediate and nonclassical monocytes as a single subset.6

Although neglected in earlier studies, the intermediate monocytes are of major clinical importance: first, we found that elevated CD14++CD16+ monocyte counts independently predict adverse outcome in patients at high cardiovascular risk.7,8 Moreover, a host of data suggests that intermediate monocytes are of significance in HIV-1 infection,9,10 given that—unlike classical and nonclassical monocytes—they selectively express CCR5, the coreceptor for HIV-1.4,8

Although CD14++CD16+ monocytes show an intermediate phenotype in many chemokine receptors (eg, CCR2 and CX3CR1), they can be clearly distinguished by distinct identifiers from CD14++CD16− and CD14+CD16++ monocytes, such as the subset-specific surface expression of CCR54,8 and of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE; CD143).11 Admittedly, so far, proof for the existence of the intermediate monocyte subset derives mainly from flow-cytometrical surface expression analysis. Flow cytometry is limited in its analytical capacity, whereas gene expression profiling provides a much more profound characterization. In line, previous knowledge on the heterogeneity of 2 major subsets of CD14++CD16− and CD16-positive monocytes has recently been extended by gene expression profiling.12-15

However, no data on the gene expression profile of the intermediate CD14++CD16+ monocyte subset exist so far because of the technically challenging procedure of separating CD16-positive monocytes into CD14++CD16+ and CD14+CD16++ cells.

To unravel heterogeneity of CD16-positive monocytes, we set out to develop a method to separate the 3 human monocyte subsets, and analyzed them in combination with an improved version of the SuperSAGE method16 to characterize the monocyte subsets' transcriptomes. This method provides digital transcriptome data in a very high resolution, as rare transcripts which remain invisible on microarrays can also be exactly quantified.

Methods

Isolation of human monocyte subsets

Twelve healthy volunteers were recruited for the study. All participants gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Saarland University Hospital.

EDTA-anticoagulated blood was drawn by venopuncture and PBMCs were immediately isolated by Ficoll-Paque (Lymphocyte Separation Medium; PAA) gradient density centrifugation. Subsequently, NK cells and neutrophils were depleted using CD56 and CD15 MicroBeads (NonMonocyte Depletion Cocktail, CD16+ Monocyte Isolation Kit; Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer's instructions. From these negatively isolated cells, human monocyte subsets were isolated according to their different CD14 and CD16 expression. First, the cells were incubated with FITC-conjugated anti-CD14 Ab (Miltenyi Biotec) and then with anti-FITC MultiSort MicroBeads (Anti-FITC MultiSort Kit; Miltenyi Biotec) to separate the pre-enriched monocytes in CD14++ and CD14+/− cells. After release of anti-FITC MultiSort MicroBeads, both fractions were incubated with CD16 MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec) and separated into 3 monocyte subsets (compare Figure 1 for a representative example). All steps of monocyte subset isolation were performed at 4°C. After each single step, purity was analyzed flow-cytometrically.

Purificationof human monocyte subsets. (A) PBMCs were isolated by Ficoll-Paque and stained with anti-CD86, anti-CD14, and anti-CD16; CD86-positive cells (monocytes) are red, whereas CD86-negative (nonmonocytic) cells are black (i). NB: Percentages refer to CD86-positive monocyte subsets among all PBMCs, excluding CD86-negative cells (eg, CD16-positive NK cells and neutrophils) which protrude into the CD14+CD16++ monocyte gate in this dot plot. (B) After depletion of NK cells and neutrophils (CD16-positive nonmonocytic cells) using CD56 and CD15 MicroBeads (not shown), negatively isolated cells were separated into CD14++ (i) and CD14+/− cells (ii) using FITC-conjugated anti-CD14 Ab and accordingly anti-FITC MultiSort MicroBeads. (C) Both fractions were incubated with CD16 MicroBeads to separate CD14++ cells into CD14++CD16− (i) and CD14++CD16+ monocytes (ii), and to purify CD14+CD16++ monocytes (iii) from CD14+/− cells. Top line: Flow cytometric analysis; bottom line: microscopic images (Keyence BZ-8000J [Keyence Deutschland] equipped with a Plan Apo 60×/1.40 oil objective lens [Nikon], magnification 30×, room temperature) after cytospin and May-Grünwald-Giemsa staining. Representative examples from 12 independent experiments are shown. In each dot plot, subset-specific percentages of monocytic cells among total cells are shown as means ± SD.

Purificationof human monocyte subsets. (A) PBMCs were isolated by Ficoll-Paque and stained with anti-CD86, anti-CD14, and anti-CD16; CD86-positive cells (monocytes) are red, whereas CD86-negative (nonmonocytic) cells are black (i). NB: Percentages refer to CD86-positive monocyte subsets among all PBMCs, excluding CD86-negative cells (eg, CD16-positive NK cells and neutrophils) which protrude into the CD14+CD16++ monocyte gate in this dot plot. (B) After depletion of NK cells and neutrophils (CD16-positive nonmonocytic cells) using CD56 and CD15 MicroBeads (not shown), negatively isolated cells were separated into CD14++ (i) and CD14+/− cells (ii) using FITC-conjugated anti-CD14 Ab and accordingly anti-FITC MultiSort MicroBeads. (C) Both fractions were incubated with CD16 MicroBeads to separate CD14++ cells into CD14++CD16− (i) and CD14++CD16+ monocytes (ii), and to purify CD14+CD16++ monocytes (iii) from CD14+/− cells. Top line: Flow cytometric analysis; bottom line: microscopic images (Keyence BZ-8000J [Keyence Deutschland] equipped with a Plan Apo 60×/1.40 oil objective lens [Nikon], magnification 30×, room temperature) after cytospin and May-Grünwald-Giemsa staining. Representative examples from 12 independent experiments are shown. In each dot plot, subset-specific percentages of monocytic cells among total cells are shown as means ± SD.

RNA isolation and construction of SuperSAGE libraries

Isolated monocyte subsets were immediately lysed, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until RNA preparation. Total RNA from lysates was isolated using the RNeasy Micro Kit (QIAGEN) including DNase treatment. From 12 donors, same aliquots of each sample were matched for SuperSAGE, leading to a total RNA amount of 12.0 μg (CD14++CD16−), 1.2 μg (CD14++CD16+), and 1.6 μg (CD14+CD16++), respectively.

SuperSAGE libraries were produced at GenXPro GmbH essentially as described by Matsumura et al,17 but with the implementation of GenXPro PCR-bias-proof technology to distinguish PCR copies from original tags. Quality assessment of the tags was performed according to Qu et al18 to reduce sequencing errors and artificial tag sequences. Tags were counted using the “GenXProgram.” Likelihoods for differential expression of the tags were calculated according to Audic and Claverie.19 The 26-bp tags were annotated to the human-refseq-database (National Center for Biotechnology Information [NCBI] from September 2010). Tags with no hits were annotated to all other mammalian refseq-mRNA databases (NCBI from September 2010). Tags matching to the same transcript were summed up to define a “transcript frequency”; P values for differential expression were also calculated based on the transcript frequencies. All SuperSAGE data are available in the Gene Express Omnibus (GEO) under accession number GSE30811.

Gene ontology information

Gene ontology (GO) information was obtained from www.GeneOntology.org for the refseq-mRNA entries. P values describing the likelihood for enrichment of GO terms were calculated by the Fisher exact test, based on transcripts that were differentially expressed with a P < 10−10.20

Flow cytometric analysis

Via flow cytometry (FACS Canto II with CellQuest Software; BD Biosciences) monocyte subsets were identified according to our previously published gating strategy.7 Briefly, monocytes were gated in a side scatter/CD86 dot plot, identifying monocytes as CD86-positive cells with monocyte scatter properties. Subpopulations of CD14++CD16−, CD14++CD16+, and CD14+CD16++ monocytes were distinguished by their surface expression pattern of the LPS receptor CD14 and the FcγIIIR CD16.

For validation, we compared this gating strategy to an alternative strategy which was recently suggested by Heimbeck et al.21 As summarized in supplemental Figure 1 and supplemental Table 1 (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the article), both gating strategies yielded virtually identical results.

For validation of SuperSAGE results, surface expression of different Ags was analyzed in 10 healthy subjects via a whole-blood assay using 100 μL of EDTA anticoagulated blood. Surface expression was quantified as median fluorescence intensity (MFI) and standardized against coated fluorescent particles (SPHEROTM; BD Biosciences). Histograms were created with FCS Express Version 3 Software (De Novo Software). Abs used in this study are summarized in supplemental Table 2.

Measurement of ROS

Isolated PBMCs were incubated with the cell-permanent carboxy-H2DFFDA (Invitrogen) in a concentration of 10μM for 15 minutes at 37°C and 5% CO2. Afterward, cells were stained with anti-CD14, anti-CD16, and anti-CD86. The intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels within the monocyte subsets were determined as MFI by flow cytometric analysis.

Phagocytosis assay

Fluoresbrite Yellow Green (YG) Carboxylate Microspheres (0.75 μm; Polysciences) were opsonized with heterologous serum (diluted to 50% with Krebs Ringers PBS) for 30 minutes at 37°C and adjusted to 108 particles/mL. One hundred microliters of citrate anticoagulated whole blood was mixed with 10 μL of opsonized particles and incubated with gentle shaking for 30 minutes at 37°C. Control samples were incubated at 4°C. Samples were stained as described in “Flow cytometric analysis,” and counts of FITC-positive cells were determined flow-cytometrically in each monocyte subset.

In vitro angiogenesis assay

Angiogenic activity of monocyte subsets was assessed using a solubilized basement membrane preparation extracted from the Engelbreth-Holm-Swarm mouse sarcoma (Matrigel Basement Membrane Matrix; BD Biosciences). Matrigel was thawed at 4°C overnight and distributed on 24-well plates (200 μL/well). Afterward, Matrigel was allowed to solidify at 37°C for at least 1 hour. In 3 independent assays, freshly isolated monocyte subsets from healthy individuals were seeded on the polymerized matrix at a density of 1 × 105 cells/well and stimulated with human VEGF (10 ng/mL; Miltenyi Biotec). Cells were cultivated at 37°C in 5% CO2. After 3 days, formation of tube-like structures was microscopically analyzed. HUVECs were used as positive control.

Proliferation assay

The monocyte subset-specific ability to induce CD4+ T-cell proliferation was analyzed by measuring the cytoplasmic dilution of CFDA-SE (Vybrant CFDA-SE Cell Tracer Kit; Invitrogen). In detail, freshly isolated monocyte subsets from 5 healthy subjects were cultivated overnight in 96-well plates at a density of 5 × 104 cells/well in the presence of 2.5 μg/mL staphylococcal enterotoxin B (SEB; Sigma-Aldrich).

Within 24 hours, autogenic CD4+ T cells were isolated using the CD4+ T Cell Isolation Kit II (Miltenyi Biotec). Purity of isolated CD4+ T cells was > 97%. CD4+ T cells were labeled with 5μM CFDA-SE at 37°C. After 10 minutes, RPMI (+5% FCS) was added in excess to stop labeling, followed by 2 washing steps. Afterward, 2 × 105 CD4+ T cells were added to stimulated monocytes. After 3 days, counts of proliferating T cells were analyzed flow-cytometrically by measuring CFDA-SE dilution, identifying T cells by anti-CD3 APC. All experiments were performed in duplicate. For negative control, labeled T cells were cultivated without monocytes and without SEB, respectively.

Results

Generation of SuperSAGE libraries

Human monocyte subsets were purified with MACS technology based on the differential CD14 and CD16 expression, yielding a purity of 98.0% ± 0.6% for CD14++CD16− monocytes, 89.3% ± 5.2% for CD14++CD16+ monocytes, and 96.3% ± 3.3% for CD14+CD16++ monocytes, with a mean viability of > 97% for all subsets (Figure 1).

Three independent SuperSAGE libraries were generated from isolated human monocyte subsets. After eliminating incomplete reads, twin ditags, ditags without complete library-identification DNA linkers, and tags which were detected only once (singletons), the total number of SuperSAGE tags was 5 487 603, comprising three 610 673 tags from CD14++CD16− monocytes, 1 189 952 tags from CD14++CD16+ monocytes, and 686 978 tags from CD14+CD16++ monocytes. These tags accounted for 154 313 unique sequences (UniTags) in the combined libraries, of which 112 873 (73.1%) matched sequences corresponding to human refseq-RNA database entries and were considered for further analysis. The remaining UniTags hit either to a nonhuman database (4773 UniTags [3.1%]), or did not hit to the refseq databases (36 667 UniTags [23.8%]), and thus represented UniTags for mitochondrial transcripts, nonannotated transcripts, and sequencing artifacts.

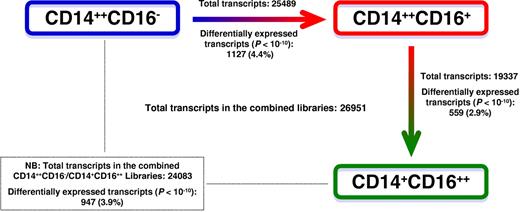

Monocyte subset-specific genes

The 112 873 UniTags which matched to the human database represented 26 951 transcripts in the combined libraries (Figure 2). The complete list of identified transcripts in the monocyte subsets is shown in supplemental Table 5. Comparing gene expression profile in pairs of monocyte subsets, CD14++CD16+ and CD14+CD16++ monocytes showed the highest similarity (Figure 2). Of 19 337 transcripts which were identified in the combined CD14++CD16+ and CD14+CD16++ libraries, 559 (2.9%) were differentially expressed with a P < 10−10, among which 258 genes were up-regulated in CD14++CD16+ monocytes, and 301 genes in CD14+CD16++ monocytes. CD14++CD16− and CD14++CD16+ monocytes could be distinguished from each other by 1127 of 25 489 identified transcripts (4.4%), whereas CD14++CD16− and CD14+CD16++ monocytes differed in the expression of 947 of 24 083 (3.9%) transcripts when applying the same cutoff value (P < 10−10).

Schematic representation of differences in gene expression between the 3 monocyte subsets. For each pair of monocyte subsets, the number of total transcripts, and the number of differentially expressed transcripts that reached a level of significance of P < 10−10 are depicted. Statistical analysis was performed according to Audic and Claverie.19

Schematic representation of differences in gene expression between the 3 monocyte subsets. For each pair of monocyte subsets, the number of total transcripts, and the number of differentially expressed transcripts that reached a level of significance of P < 10−10 are depicted. Statistical analysis was performed according to Audic and Claverie.19

Comparison of SuperSAGE versus microarray

For validation of the SuperSAGE results, we compared our data with the previously published microarray results by Ancuta et al.12 As the latter study did not distinguish between CD14++CD16+ and CD14+CD16++ monocytes, we recalculated the tag counts of CD16-positive monocytes in the present study by pooling data of CD14++CD16+ and CD14+CD16++ monocytes in a 1:1.6 ratio, based on the relative frequencies of these cells within the PBMCs.

Table 1 lists the 30 most differentially expressed genes between CD14++CD16− and CD16-positive monocytes according to Ancuta et al.12 Of note, microarray analysis and SuperSAGE found a strikingly similar expression pattern, even though some quantitative differences in the magnitude of fold-change values remain because of the different methods applied.

Comparison of SuperSAGE results with microarray data by Ancuta et al12

| Gene symbol . | Ancuta et al12 . | SuperSAGE . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD16+/CD16− ratio . | CD14++CD16− mo TPM . | CD16-positive mo TPM . | Ratio . | P . | |

| S100A12 | 0.1 | 29.6 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 8.0 × 10−22 |

| VCAN | 0.2 | 905.4 | 36.1 | 0.0 | 0 |

| CD14 | 0.2 | 1701.9 | 240.0 | 0.1 | 0 |

| CD36 | 0.2 | 106.1 | 9.4 | 0.1 | 9.6 × 10−56 |

| CD99 | 0.2 | 181.7 | 32.9 | 0.2 | 2.0 × 10−67 |

| METTL9 | 0.3 | 401.9 | 60.9 | 0.2 | 1.6 × 10−163 |

| CSF3R | 0.3 | 410.7 | 77.0 | 0.2 | 8.7 × 10−147 |

| PLBD1 | 0.3 | 945.0 | 159.8 | 0.2 | 0 |

| MS4A6A | 0.3 | 852.5 | 105.3 | 0.1 | 0 |

| ITGAM | 0.3 | 111.3 | 27.4 | 0.2 | 2.0 × 10−33 |

| SELL | 0.3 | 973.8 | 103.5 | 0.1 | 0 |

| CRTAP | 0.4 | 375.8 | 109.8 | 0.3 | 6.4 × 10−92 |

| S100A9 | 0.4 | 4796.3 | 627.8 | 0.1 | 0 |

| GPX1 | 0.4 | 1038.6 | 428.5 | 0.4 | 1.7 × 10−156 |

| PLP2 | 0.4 | 142.1 | 36.4 | 0.3 | 1.2 × 10−40 |

| LST1 | 2.5 | 128.2 | 683.2 | 5.3 | 4.5 × 10−271 |

| IFITM3 | 2.5 | 173.9 | 923.9 | 5.3 | 0 |

| SOD1 | 2.5 | 26.6 | 43.8 | 1.6 | 4.8 × 10−4 |

| IFITM2 | 2.5 | 578.0 | 2932.7 | 5.1 | 0 |

| NAP1L1 | 2.8 | 37.1 | 82.7 | 2.2 | 7.2 × 10−12 |

| CSF1R | 2.8 | 256.2 | 1227.6 | 4.8 | 0 |

| MS4A7 | 2.8 | 387.5 | 1114.8 | 2.9 | 9.6 × 10−235 |

| TCF7L2 | 3.0 | 10.5 | 91.4 | 8.7 | 6.4 × 10−50 |

| TAGLN | 3.2 | 6.1 | 54.1 | 8.9 | 1.8 × 10−30 |

| HMOX1 | 3.5 | 118.8 | 750.4 | 6.3 | 0 |

| IFITM1 | 4.5 | 2.5 | 26.4 | 10.6 | 1.0 × 10−16 |

| SIGLEC10 | 4.8 | 7.8 | 55.4 | 7.1 | 4.3 × 10−28 |

| MTSS1 | 5.7 | 14.7 | 147.4 | 10.0 | 1.2 × 10−84 |

| CDKN1C | 18.4 | 8.3 | 1712.4 | 206.3 | 0 |

| FCGR3A | 20.1 | 27.1 | 1911.6 | 70.5 | 0 |

| Gene symbol . | Ancuta et al12 . | SuperSAGE . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD16+/CD16− ratio . | CD14++CD16− mo TPM . | CD16-positive mo TPM . | Ratio . | P . | |

| S100A12 | 0.1 | 29.6 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 8.0 × 10−22 |

| VCAN | 0.2 | 905.4 | 36.1 | 0.0 | 0 |

| CD14 | 0.2 | 1701.9 | 240.0 | 0.1 | 0 |

| CD36 | 0.2 | 106.1 | 9.4 | 0.1 | 9.6 × 10−56 |

| CD99 | 0.2 | 181.7 | 32.9 | 0.2 | 2.0 × 10−67 |

| METTL9 | 0.3 | 401.9 | 60.9 | 0.2 | 1.6 × 10−163 |

| CSF3R | 0.3 | 410.7 | 77.0 | 0.2 | 8.7 × 10−147 |

| PLBD1 | 0.3 | 945.0 | 159.8 | 0.2 | 0 |

| MS4A6A | 0.3 | 852.5 | 105.3 | 0.1 | 0 |

| ITGAM | 0.3 | 111.3 | 27.4 | 0.2 | 2.0 × 10−33 |

| SELL | 0.3 | 973.8 | 103.5 | 0.1 | 0 |

| CRTAP | 0.4 | 375.8 | 109.8 | 0.3 | 6.4 × 10−92 |

| S100A9 | 0.4 | 4796.3 | 627.8 | 0.1 | 0 |

| GPX1 | 0.4 | 1038.6 | 428.5 | 0.4 | 1.7 × 10−156 |

| PLP2 | 0.4 | 142.1 | 36.4 | 0.3 | 1.2 × 10−40 |

| LST1 | 2.5 | 128.2 | 683.2 | 5.3 | 4.5 × 10−271 |

| IFITM3 | 2.5 | 173.9 | 923.9 | 5.3 | 0 |

| SOD1 | 2.5 | 26.6 | 43.8 | 1.6 | 4.8 × 10−4 |

| IFITM2 | 2.5 | 578.0 | 2932.7 | 5.1 | 0 |

| NAP1L1 | 2.8 | 37.1 | 82.7 | 2.2 | 7.2 × 10−12 |

| CSF1R | 2.8 | 256.2 | 1227.6 | 4.8 | 0 |

| MS4A7 | 2.8 | 387.5 | 1114.8 | 2.9 | 9.6 × 10−235 |

| TCF7L2 | 3.0 | 10.5 | 91.4 | 8.7 | 6.4 × 10−50 |

| TAGLN | 3.2 | 6.1 | 54.1 | 8.9 | 1.8 × 10−30 |

| HMOX1 | 3.5 | 118.8 | 750.4 | 6.3 | 0 |

| IFITM1 | 4.5 | 2.5 | 26.4 | 10.6 | 1.0 × 10−16 |

| SIGLEC10 | 4.8 | 7.8 | 55.4 | 7.1 | 4.3 × 10−28 |

| MTSS1 | 5.7 | 14.7 | 147.4 | 10.0 | 1.2 × 10−84 |

| CDKN1C | 18.4 | 8.3 | 1712.4 | 206.3 | 0 |

| FCGR3A | 20.1 | 27.1 | 1911.6 | 70.5 | 0 |

P < 10−310 is denoted as 0.

TPM indicates tags per million; and mo, monocytes.

Genes differentially expressed between CD14++CD16+ and CD14+CD16++ monocytes

Because 4 earlier studies analyzed gene expression between CD14++CD16− and CD16-positive monocytes,12-15 we deliberately chose to focus our data presentation on differences between the 2 subsets of CD16-positive monocytes (CD14++CD16+ and CD14+CD16++), which had been neglected before. Comparisons between CD14++CD16− versus CD14++CD16+ monocytes and CD14++CD16− versus CD14+CD16++ monocytes—which are not the major topic of the present report—are summarized in supplemental Tables 3 and 4.

Those 30 genes defined by a 26-hit tag which differed most significantly between CD14++CD16+ and CD14+CD16++ monocytes are presented in Table 2. CD14++CD16+ monocytes were distinguished from CD14+CD16++ monocytes by significant higher expression of genes linked to defense against microbial pathogens (LYZ, S100A8, CD14, S100A10 [for the ease of legibility, gene symbols are given in “Results”; gene titles are listed in supplemental Table 5]) and MHC II–restricted Ag processing and presentation (HLA-DRA, CD74, IFI30, HLA-DPB1, CPVL). In contrast, CD14+CD16++ monocytes expressed higher levels of genes connected to MHC I–restricted processes (HLA-B, B2M) to migration and transendothelial motility (LSP1, LYN, CFL1, MYL6) and to cell-cycle progression (CDKN1C, STK10).

Comparison of top genes differentially expressed between intermediate CD14++CD16+ and nonclassical CD14+CD16++ monocytes

| Gene symbol . | Gene title . | Tag sequence . | CD14++CD16+ TPM . | CD14+CD16++ TPM . | P . | Fold change . | Protein function . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top genes up-regulated in intermediate CD14++CD16+ monocytes compared to nonclassical CD14+CD16++ monocytes | |||||||

| HLA-DRA | MHC complex, class II, DR alpha | CATGGGGCATCTCTTGTGTACTTATT | 7564.9 | 2615.9 | 0 | 1.5 | MHC II Ag presentation |

| LYZ | Lysozyme | CATGATGTAAAAAATACAAACATTCT | 6770.6 | 1063.6 | 0 | 2.7 | Antimicrobial agent |

| CD74 | CD74 molecule, MHC class II invariant chain | CATGGTTCACATTAGAATAAAAGGTA | 30 285.4 | 13 911.5 | 0 | 1.1 | MHC II Ag processing; cell-surface receptor for MIF |

| IFI30 | IFN γ-inducible protein 30 | CATGATCAAGAATCCTGCTCCACTAA | 5312.1 | 2128.7 | 2.1 ×10−253 | 1.3 | MHC II Ag processing |

| S100A8 | S100 calcium-binding protein A8 | CATGTACCTGCAGAATAATAAAGTCA | 1557.0 | 283.7 | 8.6 ×10−171 | 2.5 | Calcium-binding protein with antimicrobial activity |

| HLA-DPB1 | MHC complex, class II, DP beta 1 | CATGTTCCCTTCTTCTTAGCACCACA | 1497.9 | 340.2 | 6.3 × 10−140 | 2.1 | MHC II Ag presentation |

| TMSB10 | Thymosin beta 10 | CATGGGGGAAATCGCCAGCTTCGATA | 3314.6 | 1650.4 | 1.8 × 10−104 | 1.0 | Organization of the cytoskeleton; cell motility, differentiation |

| SECTM1 | Secreted and transmembrane 1 | CATGACTCGAATATCTGAAATGAAGA | 1756.7 | 803.6 | 3.5 × 10−67 | 1.1 | Hematopoietic and/or immune system processes |

| FAU | Finkel-Biskis-Reilly murine sarcoma virus (FBR-MuSV) ubiquitously expressed | CATGGTTCCCTGGCCCGTGCTGGAAA | 1384.8 | 566.0 | 2.7 ×10−65 | 1.3 | Fusion protein (ubiquitin-like protein fubi and ribosomal protein S30) |

| CPVL | Carboxypeptidase, vitellogenic-like | CATGATTAATCGATTCATTTATGGAA | 470.5 | 57.9 | 5.1 × 10−65 | 3.0 | Processing of phagocytosed particles, inflammatory protease cascade |

| PPIA | Peptidylprolyl isomerase A (cyclophilin A) | CATGCCTAGCTGGATTGCAGAGTTAA | 1817.5 | 900.2 | 8.7 × 10−59 | 1.0 | Accelerate the folding of proteins; formation of infectious HIV virions |

| CD14 | CD14 molecule | CATGTGGTCCAGCGCCCTGAACTCCC | 406.2 | 56.4 | 3.0 × 10−53 | 2.8 | Mediate the innate immune response to bacterial lipopolysaccharide |

| S100A10 | S100 calcium-binding protein A10 | CATGAGCAGATCAGGACACTTAGCAA | 813.2 | 277.8 | 1.4 × 10−50 | 1.5 | Cell-cycle progression and differentiation; exo- and endocytosis |

| FOS | FBJ murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog | CATGTGGAAAGTGAATTTGAATGAAA | 287.1 | 17.8 | 2.3 × 10−50 | 4.0 | Forming the TF complex AP-1; proliferation, differentiation |

| TNFAIP2 | TNF α-induced protein 2 | CATGACTCAGCCCGGCTGATGCCTCT | 757.5 | 268.9 | 6.5 × 10−45 | 1.5 | Mediator of inflammation and angiogenesis |

| Top genes up-regulated in nonclassical CD14+CD16++ monocytes compared to intermediate CD14++CD16+ monocytes | |||||||

| CFL1 | Cofilin 1 | CATGGAAGCAGGACCAGTAAGGGACC | 2871.6 | 6395.0 | 1.8 × 10−266 | −1.2 | Actin dynamics; cell motility |

| IFITM2 | IFN-induced transmembrane protein 2 (1-8D) | CATGACCATTCTGCTCATCATCATCC | 1727.6 | 4362.8 | 3.7 × 10−230 | −1.3 | Immune response |

| GNAI2 | Guanine nucleotide-binding protein (G protein), α inhibiting activity polypeptide 2 | CATGTTTTATGGAATTGTTCACCTGG | 1270.8 | 3523.6 | 5.1 × 10−216 | −1.5 | Regulation of adenylate cyclase |

| NPC2 | Niemann-Pick disease, type C2 | CATGTCTCTTTTTCTGTCTTAGGTGG | 1286.2 | 3394.3 | 6.4 × 10−193 | −1.4 | Transport regulation of cholesterol through endosomal/lysosomal system |

| MYL6 | Myosin, light chain 6, alkali, smooth muscle and non-muscle | CATGGTGCTGAATGGCTGAGGACCTT | 2431.1 | 4885.7 | 6.2 × 10−163 | −1.0 | Regulatory light chain of myosin |

| CDKN1C | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1C (p57, Kip2) | CATGCCCATCTAGCTTGCAGTCTCTT | 948.6 | 2611.5 | 6.2 × 10−159 | −1.5 | Negative regulator of cell proliferation |

| LYN | v-yes-1 Yamaguchi sarcoma viral-related oncogene homolog | CATGATGTGTTTCACTTATGCTGTTG | 1000.9 | 2602.6 | 6.2 × 10−145 | −1.4 | Cell proliferation, migration |

| LAPTM5 | Lysosomal protein transmembrane 5 | CATGGCGGTTGTGGCAGCTGGGGAGG | 1866.4 | 3905.3 | 2.4 × 10−143 | −1.1 | Transmembrane receptor associated with lysosomes |

| OAZ1 | Ornithine decarboxylase antizyme 1 | CATGTTGTAATCGTGCAAATAAACGC | 2649.6 | 4934.8 | 1.4 × 10−135 | −0.9 | Regulation of polyamine biosynthesis |

| HLA-B | MHC, class I, B | CATGCTGACCTGTGTTTCCTCCCCAG | 4623.1 | 7133.3 | 2.6 × 10−104 | −0.6 | HLA class I heavy chain paralogue; Ag presentation |

| B2M | β2-microglobulin | CATGGTTGTGGTTAATCTGGTTTATT | 6510.0 | 9267.9 | 2.0 × 10−93 | −0.5 | Association with the MHC I heavy chain |

| STK10 | Serine/threonine kinase 10 | CATGGCAGAAGCACAGGTTCTGTACC | 359.1 | 1137.9 | 3.4 × 10−85 | −1.7 | Cell-cycle progression; involved in MAPKK1 pathway |

| PSAP | Prosaposin | CATGAAGTTGCTATTAAATGGACTTC | 6670.3 | 9190.7 | 9.0 × 10−78 | −0.5 | Catabolism of glycosphingolipids |

| CSTB | Cystatin B (stefin B) | CATGATGAGCTGACCTATTTCTGATC | 424.2 | 1186.9 | 4.5 × 10−75 | −1.5 | Thiol protease; intracellular degradation and turnover of proteins |

| LSP1 | Lymphocyte-specific protein 1 | CATGCAGGATGCTTGATGCTGCGTCC | 1138.0 | 2237.1 | 8.7 × 10−72 | −1.0 | Regulation of motility, adhesion, and transendothelial migration |

| Gene symbol . | Gene title . | Tag sequence . | CD14++CD16+ TPM . | CD14+CD16++ TPM . | P . | Fold change . | Protein function . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top genes up-regulated in intermediate CD14++CD16+ monocytes compared to nonclassical CD14+CD16++ monocytes | |||||||

| HLA-DRA | MHC complex, class II, DR alpha | CATGGGGCATCTCTTGTGTACTTATT | 7564.9 | 2615.9 | 0 | 1.5 | MHC II Ag presentation |

| LYZ | Lysozyme | CATGATGTAAAAAATACAAACATTCT | 6770.6 | 1063.6 | 0 | 2.7 | Antimicrobial agent |

| CD74 | CD74 molecule, MHC class II invariant chain | CATGGTTCACATTAGAATAAAAGGTA | 30 285.4 | 13 911.5 | 0 | 1.1 | MHC II Ag processing; cell-surface receptor for MIF |

| IFI30 | IFN γ-inducible protein 30 | CATGATCAAGAATCCTGCTCCACTAA | 5312.1 | 2128.7 | 2.1 ×10−253 | 1.3 | MHC II Ag processing |

| S100A8 | S100 calcium-binding protein A8 | CATGTACCTGCAGAATAATAAAGTCA | 1557.0 | 283.7 | 8.6 ×10−171 | 2.5 | Calcium-binding protein with antimicrobial activity |

| HLA-DPB1 | MHC complex, class II, DP beta 1 | CATGTTCCCTTCTTCTTAGCACCACA | 1497.9 | 340.2 | 6.3 × 10−140 | 2.1 | MHC II Ag presentation |

| TMSB10 | Thymosin beta 10 | CATGGGGGAAATCGCCAGCTTCGATA | 3314.6 | 1650.4 | 1.8 × 10−104 | 1.0 | Organization of the cytoskeleton; cell motility, differentiation |

| SECTM1 | Secreted and transmembrane 1 | CATGACTCGAATATCTGAAATGAAGA | 1756.7 | 803.6 | 3.5 × 10−67 | 1.1 | Hematopoietic and/or immune system processes |

| FAU | Finkel-Biskis-Reilly murine sarcoma virus (FBR-MuSV) ubiquitously expressed | CATGGTTCCCTGGCCCGTGCTGGAAA | 1384.8 | 566.0 | 2.7 ×10−65 | 1.3 | Fusion protein (ubiquitin-like protein fubi and ribosomal protein S30) |

| CPVL | Carboxypeptidase, vitellogenic-like | CATGATTAATCGATTCATTTATGGAA | 470.5 | 57.9 | 5.1 × 10−65 | 3.0 | Processing of phagocytosed particles, inflammatory protease cascade |

| PPIA | Peptidylprolyl isomerase A (cyclophilin A) | CATGCCTAGCTGGATTGCAGAGTTAA | 1817.5 | 900.2 | 8.7 × 10−59 | 1.0 | Accelerate the folding of proteins; formation of infectious HIV virions |

| CD14 | CD14 molecule | CATGTGGTCCAGCGCCCTGAACTCCC | 406.2 | 56.4 | 3.0 × 10−53 | 2.8 | Mediate the innate immune response to bacterial lipopolysaccharide |

| S100A10 | S100 calcium-binding protein A10 | CATGAGCAGATCAGGACACTTAGCAA | 813.2 | 277.8 | 1.4 × 10−50 | 1.5 | Cell-cycle progression and differentiation; exo- and endocytosis |

| FOS | FBJ murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog | CATGTGGAAAGTGAATTTGAATGAAA | 287.1 | 17.8 | 2.3 × 10−50 | 4.0 | Forming the TF complex AP-1; proliferation, differentiation |

| TNFAIP2 | TNF α-induced protein 2 | CATGACTCAGCCCGGCTGATGCCTCT | 757.5 | 268.9 | 6.5 × 10−45 | 1.5 | Mediator of inflammation and angiogenesis |

| Top genes up-regulated in nonclassical CD14+CD16++ monocytes compared to intermediate CD14++CD16+ monocytes | |||||||

| CFL1 | Cofilin 1 | CATGGAAGCAGGACCAGTAAGGGACC | 2871.6 | 6395.0 | 1.8 × 10−266 | −1.2 | Actin dynamics; cell motility |

| IFITM2 | IFN-induced transmembrane protein 2 (1-8D) | CATGACCATTCTGCTCATCATCATCC | 1727.6 | 4362.8 | 3.7 × 10−230 | −1.3 | Immune response |

| GNAI2 | Guanine nucleotide-binding protein (G protein), α inhibiting activity polypeptide 2 | CATGTTTTATGGAATTGTTCACCTGG | 1270.8 | 3523.6 | 5.1 × 10−216 | −1.5 | Regulation of adenylate cyclase |

| NPC2 | Niemann-Pick disease, type C2 | CATGTCTCTTTTTCTGTCTTAGGTGG | 1286.2 | 3394.3 | 6.4 × 10−193 | −1.4 | Transport regulation of cholesterol through endosomal/lysosomal system |

| MYL6 | Myosin, light chain 6, alkali, smooth muscle and non-muscle | CATGGTGCTGAATGGCTGAGGACCTT | 2431.1 | 4885.7 | 6.2 × 10−163 | −1.0 | Regulatory light chain of myosin |

| CDKN1C | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1C (p57, Kip2) | CATGCCCATCTAGCTTGCAGTCTCTT | 948.6 | 2611.5 | 6.2 × 10−159 | −1.5 | Negative regulator of cell proliferation |

| LYN | v-yes-1 Yamaguchi sarcoma viral-related oncogene homolog | CATGATGTGTTTCACTTATGCTGTTG | 1000.9 | 2602.6 | 6.2 × 10−145 | −1.4 | Cell proliferation, migration |

| LAPTM5 | Lysosomal protein transmembrane 5 | CATGGCGGTTGTGGCAGCTGGGGAGG | 1866.4 | 3905.3 | 2.4 × 10−143 | −1.1 | Transmembrane receptor associated with lysosomes |

| OAZ1 | Ornithine decarboxylase antizyme 1 | CATGTTGTAATCGTGCAAATAAACGC | 2649.6 | 4934.8 | 1.4 × 10−135 | −0.9 | Regulation of polyamine biosynthesis |

| HLA-B | MHC, class I, B | CATGCTGACCTGTGTTTCCTCCCCAG | 4623.1 | 7133.3 | 2.6 × 10−104 | −0.6 | HLA class I heavy chain paralogue; Ag presentation |

| B2M | β2-microglobulin | CATGGTTGTGGTTAATCTGGTTTATT | 6510.0 | 9267.9 | 2.0 × 10−93 | −0.5 | Association with the MHC I heavy chain |

| STK10 | Serine/threonine kinase 10 | CATGGCAGAAGCACAGGTTCTGTACC | 359.1 | 1137.9 | 3.4 × 10−85 | −1.7 | Cell-cycle progression; involved in MAPKK1 pathway |

| PSAP | Prosaposin | CATGAAGTTGCTATTAAATGGACTTC | 6670.3 | 9190.7 | 9.0 × 10−78 | −0.5 | Catabolism of glycosphingolipids |

| CSTB | Cystatin B (stefin B) | CATGATGAGCTGACCTATTTCTGATC | 424.2 | 1186.9 | 4.5 × 10−75 | −1.5 | Thiol protease; intracellular degradation and turnover of proteins |

| LSP1 | Lymphocyte-specific protein 1 | CATGCAGGATGCTTGATGCTGCGTCC | 1138.0 | 2237.1 | 8.7 × 10−72 | −1.0 | Regulation of motility, adhesion, and transendothelial migration |

P < 10−310 is denoted as 0. Protein function: from Entrez Gene, UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot; most representative 26-hit tags are shown. Fold change: log2(CD14++CD16+/CD14+CD16++ ratio).

TPM indicates tags per million.

Biologic and functional differences between CD14++CD16+ and CD14+CD16++ monocytes

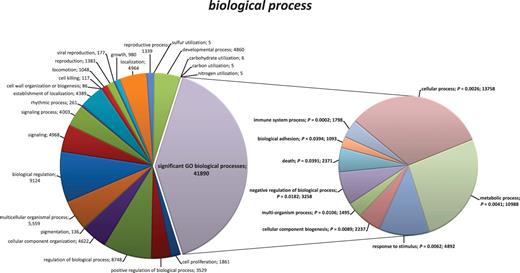

Gene ontology (GO) information was obtained from www.GeneOntology.org for the refseq-mRNA entries. P values describing the likelihood for enrichment of GO terms (enrichment P values) were calculated by the Fisher exact test, based on transcripts that were differentially expressed between the CD16-positive monocytes with a P < 10−10. A total of 15 737 transcripts were annotated to biological process (Figure 3, with GO terms showing a significant difference [enrichment P < .05] highlighted), 16 260 transcripts to molecular function (supplemental Figure 2), and 16 615 to cellular component (supplemental Figure 3). In the following, those 4 GO terms within the biological process which showed the most pronounced differences in gene expression (according to P values) are further characterized.

Pie charts of the functional annotation of identified transcripts from CD14++CD16+ and CD14+CD16++ monocytes based on GO categorization (biological process). Using GO categories, transcripts of CD14++CD16+ and CD14+CD16++ monocytes were categorized by the function of their encoded protein products. GO terms with statistical significant difference in gene expression are highlighted and projected into the right pie chart. Fisher exact test (2-tailed test) was used to compare groups for significant enrichment of particular GO classes. Numbers of transcripts for each GO term are given. All data are presented at level 2 GO categorization.

Pie charts of the functional annotation of identified transcripts from CD14++CD16+ and CD14+CD16++ monocytes based on GO categorization (biological process). Using GO categories, transcripts of CD14++CD16+ and CD14+CD16++ monocytes were categorized by the function of their encoded protein products. GO terms with statistical significant difference in gene expression are highlighted and projected into the right pie chart. Fisher exact test (2-tailed test) was used to compare groups for significant enrichment of particular GO classes. Numbers of transcripts for each GO term are given. All data are presented at level 2 GO categorization.

Immune system process

Several genes involved in immune response were differently expressed between CD14++CD16+ and CD14+CD16++ monocytes, pointing to distinct functions of these monocyte subsets in immune defense.

In detail, transcripts up-regulated (P < 10−10) in CD14++CD16+ monocytes included those linked to the innate immune response (eg, CD14, CFP, NCF2) and to MHC II–restricted processing and presentation in adaptive immune response (eg, IFI30, CD74, and further HLA-DR paralogues).

In contrast, innate immune genes up-regulated in CD14+CD16++ monocytes included those coding for complement factor D (CFD), signaling lymphocytic activation molecule family member 7 (SLAMF7), and GTP cyclohydrolase 1 (GCH1). Within adaptive immune response, CD14+CD16++ monocytes predominantly expressed, for example, sialophorin (SPN), protein kinase C, δ (PRKCD), STAT6, and MHC I–associated mechanisms (eg, B2M, HLA-B, HLA-E, and PSMB9).

Moreover, CD14++CD16+ and CD14+CD16++ showed different expression of genes related to activation of monocytes, with higher expression of allograft inflammatory factor 1 (AIF1), TGFB1, CD93, and protein tyrosine phosphatase, nonreceptor type 6 (PTPN6) in CD14++CD16+ monocytes, and higher expression of CD16, yes-1 Yamaguchi sarcoma viral-related oncogene homolog (LYN), heme oxygenase 1 (HMOX1), and Kruppel-like factor 6 (KLF6) in CD14+CD16++ monocytes.

Cellular process

Within the GO term cellular process, CD14++CD16+ and CD14+CD16++ monocytes strongly differed in the expression of genes involved in cell adhesion, oxidative stress, and phagocytosis, pointing to a distinct transendothelial trafficking potential and a greater capacity of CD14++CD16+ monocytes for generation of ROS as well as for phagocytosis of pathogens.

In detail, while CD14+CD16++ monocytes expressed significantly higher levels of mRNA for numerous genes within the adhesion process (eg, SLAMF7, RHOA, SPN, PECAM1, CYTH1, CYTIP, ITGAL, CD151), CD14++CD16+ monocytes up-regulated expression of genes for distinct adhesion molecules such as CD93, TGFBI, parvin γ (PARVG), and CSF3R.

Moreover, CD14++CD16+ monocytes up-regulated genes linked to the generation of superoxide radicals (eg, CYBA, TSPO, NCF2) and down-regulated genes coding for enzymes in the detoxification of superoxide radicals (eg, SOD2, PRDX1, GPX4).

Finally, with regard to the process of phagocytosis, CD14++CD16+ monocytes expressed significantly higher levels of mRNA for CD14, ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1 (RAC1), and CD93.

Metabolic process

Although a large number of genes connected to the GO term metabolic process were up-regulated in CD14+CD16++ monocytes (eg, STK10, GNAI2, CFL1, PSAP), suggesting an increased potential of these cells for protein metabolism, CD14++CD16+ monocytes selectively up-regulated the expression of genes linked to Ag processing (eg, CPVL, CTSB, IFI30).

Response to stimulus

Immune cells respond to diverse stimuli, such as those evoked by bacterial infection or wounding. Again, numerous genes linked to the GO terms defense response and response to wounding were differentially expressed in monocyte subsets, with higher expression of, for example, lysozyme (LYZ), S100 calcium-binding protein A8 (S100A8) and complement component 1, q subcomponent, B chain (C1QB) in CD14++CD16+ monocytes, and higher expression of tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 1B (TNFRSF1B), arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase (ALOX5), and carbohydrate sulfotransferase 2 (CHST2) in CD14+CD16++ monocytes, pointing to a differential role of monocyte subsets in dealing with biologic stress.

Unique identifiers of CD14++CD16+ monocytes

To further unravel CD14++CD16+ cells as a separate monocyte subpopulation, we aimed to identify unique markers which are selectively overexpressed in these monocytes.

Among those 258 genes which were up-regulated in CD14++CD16+ compared with CD14+CD16++ monocytes, 97 genes were likewise up-regulated in comparison to CD14++CD16− monocytes (defined as P < 10−10). Of these 97 genes, 15 top genes defined by a 26-hit tag are presented in Table 3. The majority of these 15 top genes are linked to protein turnover and MHC II–restricted protein processing and presentation, such as CD74 and other HLA-DR paralogues, IFNγ-inducible protein 30 (IFI30), calpain, small subunit 1 (CAPNS1), ras homolog gene family member B (RHOB), and cathepsin B (CTSB); others have a central role in monocyte activation, for example, protein tyrosine phosphatase nonreceptor type 6 (PTPN6), TGFβ1 (TGFB1), and allograft inflammatory factor 1 (AIF1).

Top genes up-regulated in intermediate CD14++CD16+ monocytes compared with classical CD14++CD16− and nonclassical CD14+CD16++ monocytes

| Gene symbol . | Gene title . | Tag sequence . | CD14++CD16− TPM . | CD14++CD16+ TPM . | CD14+CD16++ TPM . | Protein function . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD74 | CD74 molecule, MHC class II invariant chain | CATGGTTCACATTAGAATAAAAGGTA | 13 822.6 | 29 701.2 | 13 635.1 | MHC II Ag processing; cell-surface receptor for MIF |

| IFI30 | IFN γ–inducible protein 30 | CATGATCAAGAATCCTGCTCCACTAA | 2864.6 | 5212.8 | 2085.9 | MHC II Ag processing |

| HLA-DPB1 | MHC class II, DP β 1 | CATGTTCCCTTCTTCTTAGCACCACA | 404.4 | 1470.6 | 334.8 | MHC II Ag presentation |

| HLA-DRA | MHC class II, DR α | CATGGGGCATCTCTTGTGTACTTATT | 5090.7 | 7419.6 | 2566.3 | MHC II Ag presentation |

| SECTM1 | Secreted and transmembrane 1 | CATGACTCGAATATCTGAAATGAAGA | 614.0 | 1722.8 | 787.5 | Hematopoietic and/or immune system processes |

| AIF1 | Allograft inflammatory factor 1 | CATGTCCCTGAAACGAATGCTGGAGA | 733.4 | 2150.5 | 1362.5 | RAC signaling; proliferation; migration; vascular inflammation |

| FAU | Finkel-Biskis-Reilly murine sarcoma virus (FBR-MuSV) ubiquitously expressed | CATGGTTCCCTGGCCCGTGCTGGAAA | 606.0 | 1358.0 | 554.6 | Fusion protein (ubiquitin-like protein fubi and ribosomal protein S30) |

| TMSB10 | Thymosin β 10 | CATGGGGGAAATCGCCAGCTTCGATA | 2257.8 | 3253.1 | 1618.7 | Organization of the cytoskeleton; cell motility, differentiation |

| PPIA | Peptidylprolyl isomerase A (cyclophilin A) | CATGCCTAGCTGGATTGCAGAGTTAA | 1058.3 | 1782.4 | 882.1 | Accelerate the folding of proteins; formation of infectious HIV virions |

| PTPN6 | Protein tyrosine phosphatase, nonreceptor type 6 | CATGCCTCAGCCCTGACCCTGTGGAA | 264.8 | 892.5 | 522.6 | Regulation of cell growth, differentiation, mitotic cycle |

| TGFB1 | TGF β 1 | CATGGGGGCTGTATTTAAGGACACCC | 170.9 | 569.8 | 263.5 | Regulation of proliferation, differentiation, adhesion, migration |

| SAT1 | Spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase 1 | CATGTTTGAAATGAGGTCTGTTTAAA | 866.0 | 1979.1 | 1502.2 | Catalyzes the acetylation of polyamines |

| CAPNS1 | Calpain, small subunit 1 | CATGCCCCAGTTGCTGATCTCTAAAA | 261.4 | 657.2 | 331.9 | Regulatory subunit of nonlysosomal thiol-protease |

| RHOB | ras homolog gene family, member B | CATGCACACAGTTTTGATAAAGGGCA | 55.4 | 355.5 | 164.5 | Intracellular protein trafficking |

| CTSB | Cathepsin B | CATGTGGGTGAGCCAGTGGAACAGCG | 255.9 | 509.3 | 179.0 | Degradation and turnover of proteins; maturation MHC II complex |

| Gene symbol . | Gene title . | Tag sequence . | CD14++CD16− TPM . | CD14++CD16+ TPM . | CD14+CD16++ TPM . | Protein function . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD74 | CD74 molecule, MHC class II invariant chain | CATGGTTCACATTAGAATAAAAGGTA | 13 822.6 | 29 701.2 | 13 635.1 | MHC II Ag processing; cell-surface receptor for MIF |

| IFI30 | IFN γ–inducible protein 30 | CATGATCAAGAATCCTGCTCCACTAA | 2864.6 | 5212.8 | 2085.9 | MHC II Ag processing |

| HLA-DPB1 | MHC class II, DP β 1 | CATGTTCCCTTCTTCTTAGCACCACA | 404.4 | 1470.6 | 334.8 | MHC II Ag presentation |

| HLA-DRA | MHC class II, DR α | CATGGGGCATCTCTTGTGTACTTATT | 5090.7 | 7419.6 | 2566.3 | MHC II Ag presentation |

| SECTM1 | Secreted and transmembrane 1 | CATGACTCGAATATCTGAAATGAAGA | 614.0 | 1722.8 | 787.5 | Hematopoietic and/or immune system processes |

| AIF1 | Allograft inflammatory factor 1 | CATGTCCCTGAAACGAATGCTGGAGA | 733.4 | 2150.5 | 1362.5 | RAC signaling; proliferation; migration; vascular inflammation |

| FAU | Finkel-Biskis-Reilly murine sarcoma virus (FBR-MuSV) ubiquitously expressed | CATGGTTCCCTGGCCCGTGCTGGAAA | 606.0 | 1358.0 | 554.6 | Fusion protein (ubiquitin-like protein fubi and ribosomal protein S30) |

| TMSB10 | Thymosin β 10 | CATGGGGGAAATCGCCAGCTTCGATA | 2257.8 | 3253.1 | 1618.7 | Organization of the cytoskeleton; cell motility, differentiation |

| PPIA | Peptidylprolyl isomerase A (cyclophilin A) | CATGCCTAGCTGGATTGCAGAGTTAA | 1058.3 | 1782.4 | 882.1 | Accelerate the folding of proteins; formation of infectious HIV virions |

| PTPN6 | Protein tyrosine phosphatase, nonreceptor type 6 | CATGCCTCAGCCCTGACCCTGTGGAA | 264.8 | 892.5 | 522.6 | Regulation of cell growth, differentiation, mitotic cycle |

| TGFB1 | TGF β 1 | CATGGGGGCTGTATTTAAGGACACCC | 170.9 | 569.8 | 263.5 | Regulation of proliferation, differentiation, adhesion, migration |

| SAT1 | Spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase 1 | CATGTTTGAAATGAGGTCTGTTTAAA | 866.0 | 1979.1 | 1502.2 | Catalyzes the acetylation of polyamines |

| CAPNS1 | Calpain, small subunit 1 | CATGCCCCAGTTGCTGATCTCTAAAA | 261.4 | 657.2 | 331.9 | Regulatory subunit of nonlysosomal thiol-protease |

| RHOB | ras homolog gene family, member B | CATGCACACAGTTTTGATAAAGGGCA | 55.4 | 355.5 | 164.5 | Intracellular protein trafficking |

| CTSB | Cathepsin B | CATGTGGGTGAGCCAGTGGAACAGCG | 255.9 | 509.3 | 179.0 | Degradation and turnover of proteins; maturation MHC II complex |

Protein function: from Entrez Gene, UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot; most representative 26-hit tags are shown.

TPM indicates tags per million.

Validation of monocyte subset specific markers identified by SuperSAGE

Finally, we aimed to test the biologic relevance of SuperSAGE data by flow cytometry and functional analyses.

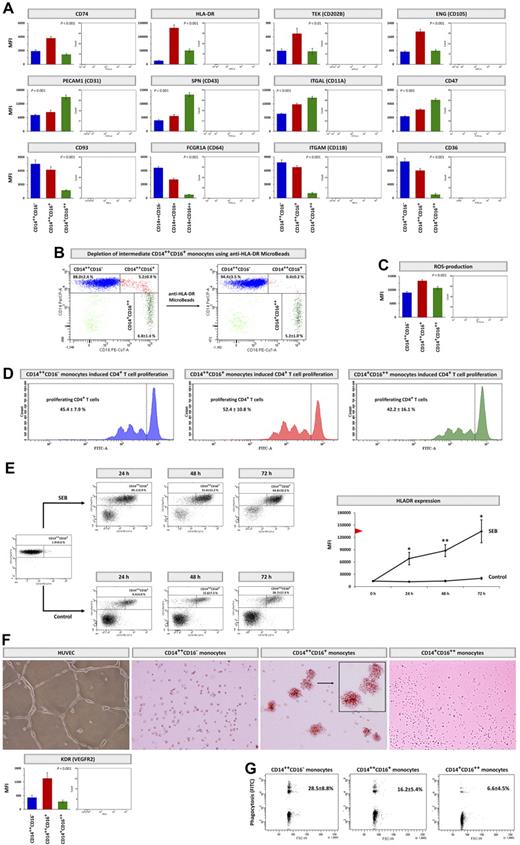

Among the 97 genes which were found to be selectively overexpressed in CD14++CD16+ monocytes (reaching predefined level of statistical significance with a P < 10−10), only few genes coding for surface proteins (eg, CD74 and HLA-DR) are accessible for flow cytometry. Therefore, we additionally analyzed further genes which again are up-regulated in CD14++CD16+ monocytes in SuperSAGE analysis, despite formally not reaching the strict statistical significance, such as the 2 proangiogenic markers endoglin (ENG) and the TEK tyrosine kinase (CD202B, angiopoietin receptor). As depicted in Figure 4A, flow cytometric analysis confirmed overexpression of these 4 markers on protein level.

Monocyte subset-specific identifiers. (A) Surface expression of distinct markers on CD14++CD16− monocytes (blue columns), CD14++CD16+ monocytes (red columns), and CD14+CD16++ monocytes (green columns) performed by flow cytometry. Data were measured as median fluorescence intensity (MFI) and presented as means ± SEM. Background fluorescence (measured in negative controls) was subtracted. Statistical analysis was performed using the Kruskal-Wallis test. (B) NK cells and neutrophil-depleted PBMCs before (left dot plot) and after (right dot plot) incubation with anti–HLA-DR MicroBeads and subsequent negative isolation. (C) Flow cytometric analysis of spontaneous intracellular ROS levels within the 3 monocyte subsets using the ROS-detection reagent carboxy-H2DFFDA. Data are presented and analyzed as described in panel A. (D) CD4+ T-cell proliferation, measured flow-cytometrically as cytoplasmic dilution of CFDA-SE. Monocyte subsets were isolated, stimulated with SEB (2.5 μg/mL), and cultivated with CFDA-SE–labeled CD4+ T cells for 3 days. After gating for CD3-positive cells, percentages of proliferating CD4+ T cells were determined and denoted as means ± SD. Representative examples of 5 independent experiments are shown. (E) Stimulation of isolated CD14++CD16− monocytes with 2.5 μg/mL SEB versus control. After 24, 48, and 72 hours, percentages of CD14++CD16+ monocytes (left panels) and expression of HLA-DR (right panel) of total events was determined flow-cytometrically. Percentages of CD14++CD16+ monocytes derived from CD14++CD16− monocytes are given as means ± SD. Representative examples of 5 independent experiments are shown. HLA-DR MFI was measured as described in panel A. Red arrowhead marks HLA-DR expression of unstimulated CD14++CD16+ monocytes (compare panel A). HLA-DR MFI of SEB-stimulated and control cells were compared by the paired Student t test; *P < .05, **P < .01. (F) Bottom panel: Surface expression of KDR (VEGFR2) on monocyte subsets measured by flow cytometry. Data are presented and analyzed as described in panel A. Top panel: Monocyte subsets cultivated for 3 days on Matrigel in the presence of 10 ng/mL VEGF (RPM1 medium/5% FCS). Representative examples of 3 independent experiments are shown. HUVECs were used as control cells (EGM-2 medium/5% FCS). Image acquistion was performed by the Keyence BZ-8000K microscope equipped with a Nikon Plan Apo 4×/0.2 objective and the BZ Viewer software, magnification 8-12×, room temperature. (G) Capacity to phagocyte opsonized carboxylate microspheres (0.75 μm, Yellow Green) by the 3 monocyte subsets within 30 minutes; counts of FITC-positive cells were determined flow-cytometrically and are denoted as means ± SD. Representative examples of 10 independent experiments are shown.

Monocyte subset-specific identifiers. (A) Surface expression of distinct markers on CD14++CD16− monocytes (blue columns), CD14++CD16+ monocytes (red columns), and CD14+CD16++ monocytes (green columns) performed by flow cytometry. Data were measured as median fluorescence intensity (MFI) and presented as means ± SEM. Background fluorescence (measured in negative controls) was subtracted. Statistical analysis was performed using the Kruskal-Wallis test. (B) NK cells and neutrophil-depleted PBMCs before (left dot plot) and after (right dot plot) incubation with anti–HLA-DR MicroBeads and subsequent negative isolation. (C) Flow cytometric analysis of spontaneous intracellular ROS levels within the 3 monocyte subsets using the ROS-detection reagent carboxy-H2DFFDA. Data are presented and analyzed as described in panel A. (D) CD4+ T-cell proliferation, measured flow-cytometrically as cytoplasmic dilution of CFDA-SE. Monocyte subsets were isolated, stimulated with SEB (2.5 μg/mL), and cultivated with CFDA-SE–labeled CD4+ T cells for 3 days. After gating for CD3-positive cells, percentages of proliferating CD4+ T cells were determined and denoted as means ± SD. Representative examples of 5 independent experiments are shown. (E) Stimulation of isolated CD14++CD16− monocytes with 2.5 μg/mL SEB versus control. After 24, 48, and 72 hours, percentages of CD14++CD16+ monocytes (left panels) and expression of HLA-DR (right panel) of total events was determined flow-cytometrically. Percentages of CD14++CD16+ monocytes derived from CD14++CD16− monocytes are given as means ± SD. Representative examples of 5 independent experiments are shown. HLA-DR MFI was measured as described in panel A. Red arrowhead marks HLA-DR expression of unstimulated CD14++CD16+ monocytes (compare panel A). HLA-DR MFI of SEB-stimulated and control cells were compared by the paired Student t test; *P < .05, **P < .01. (F) Bottom panel: Surface expression of KDR (VEGFR2) on monocyte subsets measured by flow cytometry. Data are presented and analyzed as described in panel A. Top panel: Monocyte subsets cultivated for 3 days on Matrigel in the presence of 10 ng/mL VEGF (RPM1 medium/5% FCS). Representative examples of 3 independent experiments are shown. HUVECs were used as control cells (EGM-2 medium/5% FCS). Image acquistion was performed by the Keyence BZ-8000K microscope equipped with a Nikon Plan Apo 4×/0.2 objective and the BZ Viewer software, magnification 8-12×, room temperature. (G) Capacity to phagocyte opsonized carboxylate microspheres (0.75 μm, Yellow Green) by the 3 monocyte subsets within 30 minutes; counts of FITC-positive cells were determined flow-cytometrically and are denoted as means ± SD. Representative examples of 10 independent experiments are shown.

To further underline the impact of these findings, we next demonstrated that those surface Ags which are selectively expressed in CD14++CD16+ cells might allow selective depletion of this monocyte subset in vitro, as shown exemplarily by using anti-HLA-DR MicroBeads (Figure 4B).

Because several genes involved in oxidative stress were up-regulated in CD14++CD16+ monocytes, we measured subset-specific spontaneous ROS levels using the ROS detection reagent H2DFFDA, and confirmed CD14++CD16+ monocytes to be the main producers of ROS within the 3 monocyte subsets (Figure 4C).

After CD14++CD16+ monocytes showed selective up-regulation of genes linked to Ag processing and presentation, we next analyzed the subset specific ability of SEB stimulated monocytes to induce CD4+ T cell proliferation. Consistently with gene expression and flow cytometric analyses, CD14++CD16+ monocytes had the highest capacity to induce CD4+ T-cell proliferation (Figure 4D).

Remarkably, despite their low HLA-DR expression, CD14++CD16− monocytes likewise showed a substantial potential for CD4+ T-cell activation. To unravel this seeming contradiction, we analyzed the fate of isolated CD14++CD16− monocytes after SEB stimulation and found these cells to differentiate toward CD14++CD16+ monocytes. Concomitantly, after 72 hours of stimulation, CD14++CD16− monocytes up-regulated expression of HLA-DR (Figure 4E) and CD74 (data not shown) toward levels similar to unstimulated CD14++CD16+ monocytes. In contrast, CD14+CD16++ monocytes did not enhance HLA-DR expression on SEB stimulation (data not shown).

Next, after we found CD14++CD16+ monocytes to selectively up-regulate central proangiogenic markers as ENG and TEK, we analyzed surface expression of KDR (VEGFR2), which also significantly contributes to angiogenesis. In line with ENG and TEK, KDR was selectively up-regulated in CD14++CD16+ monocytes (Figure 4F). To confirm a proangiogenic character of CD14++CD16+ monocytes, we analyzed their capacity to form cordlike structures in Matrigel after VEGF stimulation. Unlike CD14++CD16− and CD14+CD16++ monocytes, CD14++CD16+ monocytes selectively collocated to clusters within 3 days (Figure 4F). However, no monocyte subset formed typical HUVEC-like structures.

Analogous to specific markers of CD14++CD16+ monocytes, we also validated our SuperSAGE results for markers of CD14++CD16− and CD14+CD16++ monocytes: for CD14+CD16++ monocytes, we confirmed subset-specific expression of the 4 adhesion molecules PECAM1 (CD31), SPN (CD43), ITGAL (CD11A), and CD47 by flow cytometry (Figure 4A). For CD14++CD16− monocytes, overexpression of CD93, FCGR1A (CD64), ITGAM (CD11B), and CD36 was flow-cytometrically confirmed (Figure 4A). As these 4 proteins are involved in the phagocytosis process, we tested the biologic relevance of this overexpression and confirmed that CD14++CD16− monocytes exhibit the highest phagocytosis potential (Figure 4G).

Discussion

During the past 2 decades a dichotomized view on human monocyte heterogeneity prevailed, distinguishing between classical (CD14++CD16−) and nonclassical (CD16-positive) monocytes.

However, the existence of an intermediate monocyte subset, which had been identified several years before,4 has very recently been acknowledged in the International Consensus Statement on Monocyte Nomenclature.5 From now on, we should accordingly differentiate 3 major monocyte subsets: classical CD14++CD16−, intermediate CD14++CD16+, and nonclassical CD14+CD16++ monocytes.

Of note, the intermediate CD14++CD16+ monocyte subset is only poorly characterized, as the 2 CD16-positive monocyte subsets (CD14++CD16+ and CD14+CD16++ cells) have been analyzed together in most studies so far, as reviewed recently.6

Moreover, CD14++CD16+ monocytes are of importance in the pathology of 2 global health issues, HIV-1 infection,9,10 and cardiovascular disease.7,8 Therefore, a better understanding of this subset is clearly needed. We aimed to characterize this subset more thoroughly with whole genome transcriptome analysis focusing on differences between the CD16-positive monocytes.

Using SuperSAGE, we analyzed the expression of approximately five 500 000 tags in the 3 human monocyte subsets, and found a high level of transcriptional similarity, mostly between intermediate CD14++CD16+ and nonclassical CD14+CD16++ monocytes (97.1%, P < 10−10), arguing for a high developmental relationship. However, 559 genes showed strong differential expression between CD14++CD16+ and CD14+CD16++ monocytes; among those, 97 were strongly overexpressed in CD14++CD16+ monocytes compared with both CD14++CD16− and to CD14+CD16++ monocytes.

These 97 markers of CD14++CD16+ monocytes should be considered as only a fraction of all distinct identifiers, as we set a very strict level of significance to a P < 10−10. Thus, many differentially expressed genes were excluded, for example, CCR5 (CD195), ENG (CD105), and TEK (CD202B). Despite not formally reaching the strict predefined level of significance in SuperSAGE analysis, we could demonstrate selective expression of these molecules on protein level making them further identifiers of the intermediate monocyte subset.

Previously published whole genome expression analyses revealed biologic and functional differences between CD14++CD16− and CD16-positive monocytes.12-15 These previous analyses linked CD14++CD16− monocytes to myeloid (eg, CD14, MNDA, TREM1, CD1D, CD93) and granulocyte lineage (eg, FPR1, CSF3R, S100A8-9/12),12 and showed an increased antimicrobial potential of these cells (eg, LYZ, MPO, RNASE3, PLBD1).15 In contrast, CD16-positive monocytes were shown by previous whole genome expression analyses to be at a more advanced stage of differentiation, and to have a more DC (eg, SIGLEC10, CD43, RARA) and macrophage (eg CSF1R, MAFB, CD97, C3AR) character, thereby possessing effector functions related to Ag processing and presentation (eg, CTSL, CTSC), and suggesting diverse patterns of transendothelial migration (eg, CX3CR1, CD31).12

As previous gene expression studies did not distinguish between the 2 CD16-positive subsets, our SuperSAGE data expand current knowledge about monocyte heterogeneity and help to unequivocally delineate CD14++CD16+ monocytes from CD14+CD16++ monocytes.

The herein presented SuperSAGE analysis revealed that CD14++CD16+ monocytes are likely to be predisposed for Ag presentation, as they express genes encoding MHC II molecules (eg, CD74, HLA-DR) and genes involved in Ag processing and turnover of proteins (eg, IFI30, CAPNS1, RHOB, CTSB). This assumption is strengthened by the selective expression of CCR5 in CD14++CD16+ monocytes and the fact that DC precursors can be recruited directly from the blood to the lymphoid organs through signaling induced by CCR5-CCL3 interactions.22 Consistently, we found SEB-stimulated CD14++CD16+ monocytes to have highest capacity to activate CD4+ T-cell proliferation in functional analysis.

GO enrichment analysis revealed further biologic and functional differences between the 2 CD16-positive subsets. Among biological processes, those genes which differed most significantly between intermediate and nonclassical monocytes were connected to the immune system process (eg, CFP, NCF2, CFD, PRKCD) arguing for specialized immunologic functions in vivo. In line, the 2 CD16-positive subsets harbor a contrasting capacity for modulating inflammatory responses; for example, the production of IL-1B and TNF-α on stimulation with LPS is restricted to CD14++CD16+ monocytes.23

Many clinical and experimental studies showed a proinflammatory role of CD16-positive monocytes, as their counts rise in numerous acute and chronic inflammatory conditions,24-30 and as they represent the major producers of the inflammatory cytokines TNF-α31 and IL-12.32 In SuperSAGE analysis, CD14++CD16+ monocytes showed a high activation and inflammatory potential which is indicated by the selective up-regulation of genes linked to inflammatory processes (eg, AIF1, TGFB1). In line, we found this intermediate monocyte subset to be the main producer of ROS within the 3 monocyte subsets.

Within the transcriptome of CD14++CD16+ monocytes, the tag most frequently expressed was annotated to CD74. Interestingly, CD74 levels were recently suggested as a biomarker for atherosclerosis: in a clinical cohort study, CD74 levels were found to be associated with subclinical and overt atherosclerosis.33 Animal data support this notion because CD74-deficient Ldlr−/− mice showed reduced atherosclerosis associated with an impaired adaptive immune response to disease-specific Ags.34 These results are in line with our previous clinical data showing CD14++CD16+ monocyte counts to be independent predictors of cardiovascular outcome.7,8

As monocytes may further enhance atherogenesis via angiogenesis (eg, plaque neovascularization) and tissue remodeling, distinct angiogenic properties have been found in monocyte subsets.35,36 Elsheikh et al identified a subset of human monocytes expressing the VEGFR-2 (KDR) to have endothelial-like functional capacity.36 Furthermore, monocytes which express the angiopoetin-2 receptor TIE2 (TEK) have been characterized as highly proangiogenic cells specifically linked to tumor infiltration.35 In the present study, we demonstrated that CD14++CD16+ selectively up-regulated the expression of TIE2, KDR, and ENG, arguing for an involvement of these cells in the process of angiogenesis. In functional analysis, CD14++CD16+ monocytes selectively formed clusters on Matrigel after VEGF stimulation, confirming data from Elsheikh et al who similarly reported clustering of presumably proangiogenic, VEGFR2-expressing monocytes.36 As our results are also in accordance with the data of Murdoch et al,37 who found TIE2 expression predominantly on CD14++CD16+ monocytes, it is tempting to speculate that the chemotactic effect of angiopoetin-2, which is released by vessels in inflamed or malignant tissues, could contribute to subset-specific recruitment of CD14++CD16+ monocytes.

Transendothelial trafficking is a prerequisite for the response of monocytes to inflammatory stimuli evoked, for example, by atherosclerosis or infection. It is well known that this process is mediated via different mechanisms between CD16-positive and CD14++CD16− monocytes.38 We here show that numerous genes coding for adhesion molecules and proteins involved in transendothelial migration were also differentially expressed between the 2 CD16-positive monocyte subsets, arguing for a diverse recruiting process and migratory behavior of CD14++CD16+ and CD14+CD16++ monocytes.

Indeed, Ancuta et al4 demonstrated that fractalkine (CX3CL1)—the ligand for CX3CR1—mediates arrest and migration of CD16-positive monocytes. Notably, expression of CX3CR1 is highest in CD14+CD16++ monocytes4,8 ; additionally, SuperSAGE and FACS analysis demonstrated the highest expression of genes for further adhesion molecules in CD14+CD16++ monocytes, for example, integrin α L (ITGAL, CD11A), the integrin-associated protein CD47, sialophorin (SPN, CD43), which is a ligand for ICAM1 and the macrophage adhesion receptor sialoadhesin (SIGLEC1),39,40 and PECAM1 (CD31), which triggers both leukoendothelial adhesion and integrin-mediated migration of leukocytes into surrounding tissues.22

After transendothelial migration, phagocytosis of pathogens is a hallmark of monocyte function. CD14++CD16− were found to express a wide range of genes linked to the phagocytosis process (eg, CD93, CD64, CD32, CD36, CD14, FCN1, SIRPA). Accordingly, in functional analysis, we saw the highest phagocytic capacity in CD14++CD16− monocytes, which is in line with previously published data.23 Among the 3 monocyte subsets, genes coding for antimicrobial proteins (eg, LYZ, S100A8/9, RNASE6) were highest expressed in CD14++CD16− monocytes; therefore, this subset is likely to be predisposed to exert the first line of innate immune defense against microbial pathogens.

In contrast to Cros and coworkers,23 we found highest ROS levels in CD14++CD16+ monocytes rather than in CD14++CD16− monocytes. This is most likely attributable to the fact that we measured basal ROS production from freshly isolated cells, whereas Cros et al analyzed ROS levels after stimulation with IgG-opsonized BSA.

So far, data on monocyte heterogeneity are at times hard to interpret partly because of the lack of standards for monocyte gating. Therefore, it is unclear whether shifts in CD16-positive monocytes reported in many inflammatory diseases were caused by total rises of CD16-positive cells or rather selective increases of CD14++CD16+ or CD14+CD16++ monocytes. After the recently published consensus statement on monocyte heterogeneity nomenclature,5 we would like to encourage other groups to analyze the selective contribution of CD14++CD16+ and CD14+CD16++ monocytes in inflammatory states, which might allow a more subtle understanding of the respective pathophysiologic role of both subsets. Moreover, we feel an imminent need to standardize the gating strategy for flow cytometric analysis of monocyte subsets. Of note, we were able to validate our CD86-based gating strategy against a proposed reference strategy recently published by Heimbeck et al.21

In summary, we provide first genetic evidence for the proposed discrimination of human monocytes in classical CD14++CD16− monocytes, intermediate CD14++CD16+ monocytes, and nonclassical CD14+CD16++ monocytes. Although CD14++CD16+ monocytes show intermediate functional properties and expression of many genes, they can nevertheless be clearly distinguished by newly found unique identifiers from CD14++CD16− and CD14+CD16++ monocytes, suggesting a distinct role in the immune system process. Of note, while considering CD14++CD16+ cells as a separate monocyte subpopulation, we do not want to negate strong developmental relationships between these subsets. In vivo, monocytes are assumed to leave the BM as CD14++CD16− cells, to develop within few days to CD14++CD16+, and subsequently into CD14+CD16++, albeit formal evidence for this model is still lacking. Interestingly, we showed in vitro a differentiation of isolated CD14++CD16− toward CD14++CD16+ monocytes in the present study.

Finally, after CD14++CD16+ monocytes have been discussed as potential therapeutic targets in inflammatory conditions such as atherosclerosis,8,23,41 we are hopeful that our dataset will spur future research in this direction with the potential for new therapeutic avenues.

This article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The skilful technical assistance of Martina Wagner and Sarah Triem is greatly appreciated.

This work was supported by a grant from the Else Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung.

Authorship

Contribution: The study was designed by A.M.Z., R.-R.M., and G.H.H.; A.M.Z., B.R., and P.W. performed research; data were analyzed and interpreted by A.M.Z., K.S.R., and G.H.H.; statistical analysis was performed by A.M.Z., B.R., and P.W.; D.F. supervised the project; the manuscript was written by A.M.Z., K.S.R., and G.H.H., and critically revised by D.F; and all authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Gunnar H. Heine, Department of Internal Medicine IV, Saarland University Hospital, Homburg/Saar, Germany; e-mail: gunnar.heine@uks.eu.

![Figure 1. Purification of human monocyte subsets. (A) PBMCs were isolated by Ficoll-Paque and stained with anti-CD86, anti-CD14, and anti-CD16; CD86-positive cells (monocytes) are red, whereas CD86-negative (nonmonocytic) cells are black (i). NB: Percentages refer to CD86-positive monocyte subsets among all PBMCs, excluding CD86-negative cells (eg, CD16-positive NK cells and neutrophils) which protrude into the CD14+CD16++ monocyte gate in this dot plot. (B) After depletion of NK cells and neutrophils (CD16-positive nonmonocytic cells) using CD56 and CD15 MicroBeads (not shown), negatively isolated cells were separated into CD14++ (i) and CD14+/− cells (ii) using FITC-conjugated anti-CD14 Ab and accordingly anti-FITC MultiSort MicroBeads. (C) Both fractions were incubated with CD16 MicroBeads to separate CD14++ cells into CD14++CD16− (i) and CD14++CD16+ monocytes (ii), and to purify CD14+CD16++ monocytes (iii) from CD14+/− cells. Top line: Flow cytometric analysis; bottom line: microscopic images (Keyence BZ-8000J [Keyence Deutschland] equipped with a Plan Apo 60×/1.40 oil objective lens [Nikon], magnification 30×, room temperature) after cytospin and May-Grünwald-Giemsa staining. Representative examples from 12 independent experiments are shown. In each dot plot, subset-specific percentages of monocytic cells among total cells are shown as means ± SD.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/118/12/10.1182_blood-2011-01-326827/4/m_zh89991178390001.jpeg?Expires=1765886585&Signature=TMBgx4z7todlMc7x-n-uC88-BumEY7sPSmZVCQTfK7EfFkyuVwqnzsHq9hy1fZ0z3vovKgRCpSVDcmKmd2GHGiuCoaMQ2MR2dnGnKAy4~9poawbiCUJoO-oBgmNllVFX0ZkLhlhm2ARzbafnUQsI~Dk-el4SMiwF41fhvOHL3R6P1wBE5VYD~6rWoEoRJuGG~SQO5ymQdhoni4upZUGmIJsct-6-uxtp6y2wj8u9xZmsViZ9cUlqSNtdpyUq-V~D9AALVHlC87gtBxlWLsOgi6YnyQWG6SdD5PGQzr2H3bHU~2Pc6rUf6jFHhWtpJDCuA6iS1FwZNesAcZPQxmui2Q__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal