Abstract

We have reported that mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) can be selectively induced in vitro to differentiate into thymic epithelial cell progenitors (TEPs). When placed in vivo, these mESC-derived TEPs differentiate into cortical and medullary thymic epithelial cells, reconstitute the normal thymic architecture, and enhance thymocyte regeneration after syngeneic BM transplantation (BMT). Here, we show that transplantation of mESC-derived TEPs results in the efficient establishment of thymocyte chimerism and subsequent generation of naive T cells in both young and old recipients of allo-geneic BM transplant. GVHD was not induced, whereas graft-versus-tumor activity was significantly enhanced. Importantly, the reconstituted immune system was tolerant to host, mESC, and BM transplant donor antigens. Therefore, ESC-derived TEPs may offer a new approach for the rapid and durable correction of T-cell immune deficiency after BMT, and the induction of tolerance to ESC-derived tissue and organ transplants. In addition, ESC-derived TEPs may also have use as a means to reverse age-dependent thymic involution, thereby enhancing immune function and decreasing infection rates in the elderly.

Introduction

BM transplantation (BMT) is widely used in the treatment of a variety of hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic diseases. However, BM transplant recipients are often subject to prolonged periods of T-cell deficiency, which is associated with high risk of common and opportunistic infections, as well as occurrence and relapse of cancers.1-4 T-cell development in the thymus depends not only on the availability of thymocyte progenitors but also on the thymic microenvironment, of which thymic epithelial cells (TECs) are the main components.5,6 However, TECs are vulnerable to injury from radiation, chemotherapy, immunosuppressive drugs, infection, and GVHD after BMT.7,8 In addition, TECs undergo a qualitative and quantitative loss over time, which is believed to be one of the main factors responsible for age-dependent thymic involution.3,9

We reported previously that mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) could be selectively induced to differentiate into EpCAM1+ thymic epithelial cell progenitors (TEPs) in vitro. Furthermore, adoptive transfer of mESC-derived TEPs into syngeneic BM transplant recipients enhanced thymocyte reconstitution and increased the numbers and functions of peripheral T cells.10 In the current study, we investigated whether mESC-derived TEPs could enhance thymocyte regeneration after allogeneic BMT (allo-BMT), a more clinically relevant model. We show here that transplantation of mESC-derived TEPs enhances thymopoiesis, leading to increased numbers of peripheral T cells in both young and old allo-BM transplant recipients. We demonstrated that the T cells in these recipients were tolerant to both host and mESC antigens. Moreover, GVHD was not induced, but graft-versus-tumor (GVT) activity was significantly enhanced in these recipients.

Methods

Mice

Four- to 10-week-old C57BL/6 (B6), BALB/c, B6D2F1/j, 129SVEVTac, CBA, and nude mice were purchased from Taconic, Harlan, the National Cancer Institute, and The Jackson Laboratory. One- to 2-month-old and 12- to 14-month-old 129B6F2 mice were bred in house. Enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) transgenic mice that were backcrossed to the C57BL/6 genetic background were obtained from Dr Goldschneider (University of Connecticut Health Center). Mice were used according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Cell culture

TC-1 and E14TG2a-Tau-GFP mESCs (derived from 129SVEVTac and 129 Ola mice, respectively) were maintained on irradiated murine embryonic fibroblasts in DMEM medium with 15% FCS and 103 U/mL leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF).10 For TEC differentiation, undifferentiated mESCs were cultured in 10 μg/mL collagen IV (from R&D Systems) precoated 6-well culture plates containing differentiation medium (mESC medium without leukemia inhibitory factor) and human fibroblast growth factor 7 (20 ng/mL), human fibroblast growth factor 10 (20 ng/mL), human bone morphogenetic protein 4 (20 ng/mL), and human epithelial growth factor (50 ng/mL; R&D Systems), as we previously described.10 The medium and growth factors were changed every 3-4 days. Differentiated mESCs were harvested at day 10 by treating the cells with 2 mg/mL collagenase IV.

Intrathymic injection

The thymus was surgically exposed, and mESC-derived EpCAM1+ cells or EpCAM1− cells (or PBS) were injected into the anterior superior portion of the thymus with the use of a syringe (with attached 28-gauge needle) mounted on a Tridek Stepper (Indicon Inc), as described.10 The sternum was closed with absorbable sutures, and the skin incision was closed with Nexaband Liquid (Veterinary Products).

BMT procedure

BM cell suspensions were harvested from mice by flushing the marrow from the femurs and tibias with cold RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen) supplemented with sodium bicarbonate (2 mg/mL) and 1% HEPES (1.5M). T cell–deleted (TCD) BM cells were prepared by incubating the BM cell suspensions with saturating amounts of rat anti-CD4 (clone GK1.5), anti-CD8 (clone 2.43), and anti-Thy1.2 (clone 30-H-12), developed with goat anti–rat IgG magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec) and running through an immunomagnetic depletion column, as described.10 Recipients received 900-1200 cGy total body irradiation (100-110 cGy/min) from a 137Cs source (Gamma Cell 40 Irradiator; Atomic Energy of Canada). Two to 4 hours later, the mice were injected intrathymically with mESC-derived cells (or PBS) followed by intravenous injection of 5 × 106 TCD BM the next day.

Mixed leukocyte reactions

Splenocytes (normalized to 1 × 105 cells/well) from BM transplant recipients were cultured in the presence or absence of irradiated (2000 cGy) splenocytes (2 × 105 cells/well) from different mouse strains in a 96-well plate for 5 days. [3H] thymidine (1 μCi [0.037 Bq]) was added to each well for the final 12 hours of culture. Incorporation of [3H] thymidine was measured as counts per minute (CPM) by liquid scintillation spectroscopy. Counts are presented as stimulation index (CPM in mixed leukocyte reactions [MLRs]/CPM in spontaneous proliferation).

Kidney capsule grafting

Embryonic body (EB) formation was performed as described.11 Undifferentiated mESCs or EBs from 106 mESCs were grafted under the kidney capsule of mice as we previously described.10 Four weeks later, the formation of teratomas was assessed by histology. Acceptance of the grafted tissues was defined as an increase in diameter to > 5 mm, vascularization, and the lack of leukocyte infiltrate and tissue damage.

Assessment of GVHD

The severity of GVHD was evaluated with a clinical GVHD scoring system as described.12-14 In brief, BM transplant recipients in coded cages were ear tagged and individually scored every week for 5 clinical parameters on a scale from 0 to 2: weight loss, posture, activity, fur texture, and skin integrity. A clinical GVHD index was generated by summation of the 5 criteria scores (maximum index = 10). Animals were killed at day 90 after BMT, and GVHD target organs (small bowel, large bowel, and liver) were harvested for histopathologic analysis. Briefly, organs were preserved with formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin/eosin. A semiquantitative score consisting of 19-22 different parameters associated with GVHD was calculated, as described.12-14

Assessment of GVT

B16F10 melanoma cells (1 × 105) were injected subcutaneously into the flank of BM transplant recipients on day 14 after BMT. Tumor volume (V) was determined twice weekly by caliper measurements of the shortest (A) and longest (B) diameter, using the formula V = (A2B)/2.

Subcutaneous injection of mESC-EpCAM1+ cell reaggregates

TC-1 mESC-EpCAM1+ or EpCAM1− cells (5 × 105) and CD4−CD8−CD45+ thymocytes (2 × 105) from 1-month-old C57BL/c mice were mixed and reaggregated in vitro for 24-48 hours, as described.10,15 The solidified reaggregate was transplanted subcutaneously into 1-month-old nude mice.16 Three months later, the numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in axillary and inguinal lymph nodes were evaluated.

Immunomagnetic cell separation

Single-cell suspensions of mESC-derived cells were stained with rat anti–mouse EpCAM1 antibody, washed, and stained with anti–rat IgG MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec; http://www.miltenyibiotec.com). EpCAM1+ and EpCAM1− cells were positively and negatively selected with MACS immunomagnetic separation system (Miltenyi Biotec), as described.10

Detection of recent thymic emigrants

Anesthetized animals were injected intrathymically with 10 μL of a 5-mg/mL solution of sulfosuccinimidyl-6-(biotinamido) hexanoate (sulfo-NHS-LC biotin; Pierce). After 24 hours, splenocytes were stained with streptavidin-conjugated PerCP-Cy5.5 and anti-CD3 antibody and analyzed by flow cytometry as described.17

Anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 T-cell proliferation assay

Splenocytes were stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3 (clone 145-2c 11) and anti-CD28 (clone 37.51) at 5 μg/mL. Cells were cultured for 4 days and pulsed with [3H] thymidine (1 μCi [0.037 Bq]) for the last 12 hours. Incorporation of [3H] thymidine was determined by a liquid scintillation spectroscopy. Stimulation index was calculated as the ratio of the CPM from stimulated cells over the CPM from unstimulated cells.

ELISPOT assay

ELISPOT assay measuring IFN-γ was used to assess the in vitro T-cell responses to stimulation with B16F10 cells. Splenocytes, containing 1 × 105 T cells/well, and irradiated cancer cells (1 × 105/well) were incubated for 2 days in 96-well plates (Millipore) coated with anti–mouse IFN-γ antibody (clone R4-6A2) and blocked with RPMI media supplemented with 10% FCS. The wells were then washed and incubated with biotinylated anti–mouse IFN-γ antibody (clone XMG1.2). Reactions were visualized and counted with the streptavidin-peroxidase system.18

Flow cytometric analysis

TECs were isolated by flow cytometry with the use of the protocol of Gray et al.19 Single-cell suspensions of thymocytes and splenic cells were stained with the fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies as described.20 For intracellular staining, the cells were first permeabilized with a BD Cytofix/Cytoperm solution for 20 minutes at 4°C. Direct or indirect staining of fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies included CD4 (clone RM45), CD8 (clone 53-6.7), CD25 (clone PC61), CD44 (clone IM7), CD62L (clone MEL14), CD117 (clone 2B8), CD127 (clone SB199), BP-1 (clone 6C3), CD45 (clone 30-F11), I-Ab (clone AF6-120.1), H-2Kd (clone SF1-1.1), EpCAM1 (clone G8.8), IL-2 (clone JES6-5H4), IFN-γ (clone XMG1.2), TNFα (clone MP6-XT22), and a panel of TCR Vβ clonotypes (BioLegend, BD Biosciences, or eBioscience). Early thymocyte progenitors (ETPs) were identified by phenotypic analysis (Lin− c-kit+ IL-7Rα− CD44+CD25−) as described.21-24 An antibody cocktail, composed of antibodies against TER-119 (clone TER-119), B220 (clone RA3-6B2), CD19 (clone 1D3), IgM (clone RMM-1), Gr-1 (clone RB6-8C5), CD11b (clone M1/70), CD11c (clone N418), NK1.1 (clone NK136), TCRβ (clone H57-597), CD3e (clone 145-2C11), and CD8α (clone 53-6.7), was used to identify lineage-negative (lin−) cells. The samples were analyzed on a FACSCalibur or LSR II flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson).

Statistical analysis

P values were based on the 2-sided Student test. A confidence level > 95% (P < .05) was determined to be significant.

Results

mESC-derived TEPs develop into TECs and support thymopoiesis when injected into young mice after allo-BMT

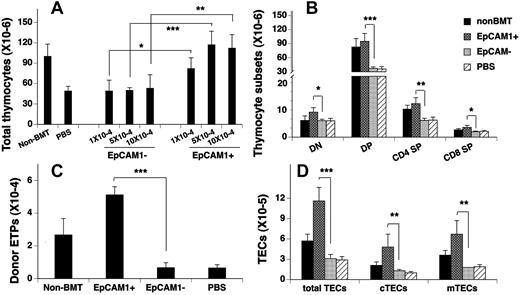

We previously reported that the intrathymic injection of 5 × 104 mESC-derived EpCAM1+ TEPs significantly enhanced thymopoiesis in syngeneic BM transplant recipients.10 To determine whether this would also occur in allo-BM transplant recipients, 4- to 8-week-old lethally irradiated C57BL/6 mice (H-2b) were injected intrathymically with 1 × 104, 5 × 104, or 10 × 104 TC-1(H-2b) mESC-derived EpCAM1+ or EpCAM1− cells (or PBS) and intravenously with TCD BM from BALB/c (H-2d) mice. Thymic cellularity was analyzed 30 days later. As shown in Figure 1A, the total number of thymocytes was significantly reduced in PBS or EpCAM1− cell–treated BMT mice, compared with unmanipulated control mice (non-BMT control). In contrast, the total number of thymocytes was markedly increased in EpCAM1+ cell–treated BMT mice, and all thymocyte subsets were affected proportionately (Figure 1B). Because 5 × 104 EpCAM1+ cells were optimal, we used this dose in all subsequent experiments.

Transplantation of mESC-derived TEPs improves thymic reconstitution after allogeneic BMT. (A) Lethally irradiated C57BL/6 mice were injected intrathymically with 1 × 104, 5 × 104, and 10 × 104 TC-1 mESC-derived EpCAM1+, EpCAM1− cells (or PBS) and intravenously with 5 × 106 TCD BM from BALB/c mice. Thirty days after BMT, thymic cellularity was analyzed. (B-D) Lethally irradiated C57BL/6 mice were injected intrathymically with 5 × 104 mESC-derived EpCAM1+, EpCAM1− cells, or PBS, and intravenously with 5 × 106 TCD BM from BALB/c mice. Thirty days after BMT, the numbers of (B) thymocyte subsets, including CD4 and CD8 double-negative (DN), double-positive (DP), and CD4 or CD8 single-positive (SP) cells; (C) donor-origin ETPs (lin−IL-7Rα −c-Kit+CD44+CD25−), and (D) total TECs (CD45−EpCAM1+MHC II+), cTECs (CD45−EpCAM1+MHC II+Ly51+), and mTECs (CD45−EpCAM1+MHC II+Ly51−) were quantified by flow cytometry. Mean percentages of donor-origin thymocytes in 5 × 104 mESC-derived EpCAM1+ cell–, EpCAM1− cell–, or PBS-treated BM transplant recipients are 89.6%, 88.7%, and 88.6%, respectively. Means ± SDs are presented (n = 5-6). *P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .001. The data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

Transplantation of mESC-derived TEPs improves thymic reconstitution after allogeneic BMT. (A) Lethally irradiated C57BL/6 mice were injected intrathymically with 1 × 104, 5 × 104, and 10 × 104 TC-1 mESC-derived EpCAM1+, EpCAM1− cells (or PBS) and intravenously with 5 × 106 TCD BM from BALB/c mice. Thirty days after BMT, thymic cellularity was analyzed. (B-D) Lethally irradiated C57BL/6 mice were injected intrathymically with 5 × 104 mESC-derived EpCAM1+, EpCAM1− cells, or PBS, and intravenously with 5 × 106 TCD BM from BALB/c mice. Thirty days after BMT, the numbers of (B) thymocyte subsets, including CD4 and CD8 double-negative (DN), double-positive (DP), and CD4 or CD8 single-positive (SP) cells; (C) donor-origin ETPs (lin−IL-7Rα −c-Kit+CD44+CD25−), and (D) total TECs (CD45−EpCAM1+MHC II+), cTECs (CD45−EpCAM1+MHC II+Ly51+), and mTECs (CD45−EpCAM1+MHC II+Ly51−) were quantified by flow cytometry. Mean percentages of donor-origin thymocytes in 5 × 104 mESC-derived EpCAM1+ cell–, EpCAM1− cell–, or PBS-treated BM transplant recipients are 89.6%, 88.7%, and 88.6%, respectively. Means ± SDs are presented (n = 5-6). *P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .001. The data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

ETPs (lin− IL-7Rα −c-Kit+CD44+CD25−) constitute a minor subset of double-negative 1 (CD25− CD44+) thymocytes and are thought to represent canonical thymocyte progenitors.21-25 As shown in Figure 1C, the number of ETPs in EpCAM1+ cell–treated BMT mice was ∼ 7-fold above that in PBS- or EpCAM1− cell–treated BMT mice, and 2-fold above that in non-BMT control mice.

Consistent with our previous data in syngeneic BM transplant recipients,10 mESC-derived EpCAM1+ cell treatment of allo-BMT mice significantly increased the number of TECs to ∼ 2-fold above normal control levels and affected both cTECs (CD45−EpCAM1+MHC II+Ly51+) and mTECs (CD45−EpCAM1+MHC II+Ly51−; Figure 1D). Again, with the use of GFP+ (E14TG2a-Tau) mESCs, 61%-73% of TECs in EpCAM1+ cell–treated mice were of mESC donor origin. Furthermore, the increases in TECs and thymocyte numbers were maintained for ≥ 90 days (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Similar results were obtained in a BMT model that MHC matches with minor histocompatibility antigen disparities (B6→B6D2F1; supplemental Figure 2). Taken together, these data suggest that by generating cTECs and mTECs in vivo, mESC-derived TEPs rapidly and durably enhance thymocyte reconstitution after allogeneic BMT.

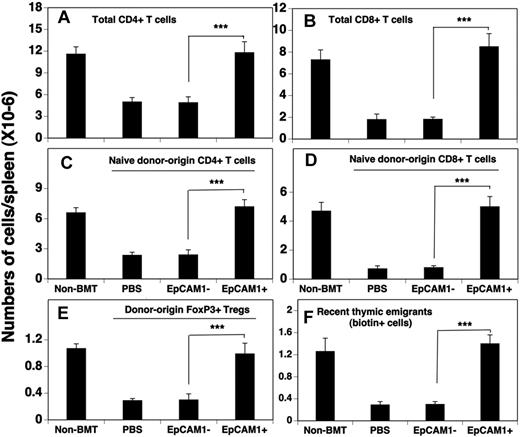

mESC-derived TEPs enhance the number and function of peripheral T cells after allo-BMT

Having found that thymocyte numbers and subset composition appeared normal after mESC-derived TEP transfer into allo-BM transplant recipients, we next wanted to determine whether peripheral T cells were also successfully reconstituted. In these experiments, the reconstitution of splenic T cells was analyzed 30 days after injection of mESC-derived TEPs and BMT. As shown in Figure 2A and B, EpCAM1+ cell treatment increased the numbers of total CD4+ and CD8+ T cells to the levels observed in non-BMT control mice and ∼ 3-fold above those observed in mice treated with EpCAM1− cells or PBS. Further analysis showed that naive (CD62LhiCD44lo) donor-origin CD4+ and CD8+ T cells accounted for most of the enhanced T-cell production (Figure 2C-D), and that ∼ 12% of the CD4+ donor-origin cells were Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs; Figure 2E). To confirm that the increased number of naive donor-origin T cells in the periphery of EpCAM1+ cell–treated mice was because of increased number of recent thymic emigrants, groups of BM transplant recipients were injected intrathymically with biotin on day 30, and the number of biotin-labeled T cells in the spleen was determined 24 hours later. The results indicated that ∼ 4 times more biotin-labeled T cells (including ∼ 11% Tregs) appeared in the EpCAM1+ cell–treated mice compared with the EpCAM1− cell–treated or PBS-treated mice (Figure 2F). Taken together, these results suggest that enhanced thymopoiesis in mESC-derived EpCAM1+ cell–treated mice result in increased thymic output, leading to normal numbers of naive CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, and Tregs in the periphery.

mESC-derived TEP treatment results in enhanced numbers of total, naive, and regulatory T cells in the spleen after allo-BMT. (A-E) Lethally irradiated C57BL/6 mice were injected intrathymically with mESC-derived EpCAM1+, EpCAM1− cells, or PBS, and intravenously with TCD-BM from BALB/c mice as in Figure 1B. Thirty days after BMT, the numbers of splenic (A-B) total, (C-D) donor-origin naive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, and (E) donor-origin regulatory T cells (CD4+ CD25+ FoxP3+) were evaluated by flow cytometry. (F) Groups of mice were injected intrathymically with biotin at 30 days after BMT. After 24 hours of in vivo labeling, the export of thymus-derived T cells into the spleen was evaluated. Means ± SDs are presented (n = 5-6). ***P < .001. The data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

mESC-derived TEP treatment results in enhanced numbers of total, naive, and regulatory T cells in the spleen after allo-BMT. (A-E) Lethally irradiated C57BL/6 mice were injected intrathymically with mESC-derived EpCAM1+, EpCAM1− cells, or PBS, and intravenously with TCD-BM from BALB/c mice as in Figure 1B. Thirty days after BMT, the numbers of splenic (A-B) total, (C-D) donor-origin naive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, and (E) donor-origin regulatory T cells (CD4+ CD25+ FoxP3+) were evaluated by flow cytometry. (F) Groups of mice were injected intrathymically with biotin at 30 days after BMT. After 24 hours of in vivo labeling, the export of thymus-derived T cells into the spleen was evaluated. Means ± SDs are presented (n = 5-6). ***P < .001. The data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

To assess the functions of peripheral T cells, we first examined cell proliferation in response to TCR stimulation. As shown in Figure 3A, 1 month after BMT, splenocytes (normalized to 1 × 105 T cells/well) from EpCAM1− cell– or PBS-treated BM transplant recipients had a decreased proliferative capacity. In contrast, the proliferative ability of splenocytes from EpCAM1+ cell–treated BMT mice was restored to the level that was observed in normal non-BMT control mice. We then analyzed cytokine-producing T cells and found that a significantly greater fraction of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from EpCAM1+ cell–treated BMT mice was able to produce IFN-γ, IL-2, and TNFα after stimulation, compared with those from EpCAM1− cell– or PBS-treated BMT mice (Figure 3B-C). To determine whether the induction of antigen-specific T cell–mediated immunity was facilitated, groups of the BM transplant recipients were vaccinated with ovalbumin (OVA) 2 weeks after BMT. OVA-specific T-cell responses in these mice were then evaluated 2 weeks after vaccination. As shown in Figure 3D, T cells purified from OVA-vaccinated EpCAM1+ cell–treated mice exhibited higher rates of proliferation in response to in vitro stimulation with OVA, compared with T cells purified from vaccinated PBS or EpCAM1− cell–treated mice. These results are consistent with our previous finding that T cells in EpCAM1+ cell–treated syngeneic BM transplant recipients have a higher ability to proliferate and to produce cytokines after stimulation with T-cell mitogens and alloantigens.10 Taken together, these finding suggest that the number and functions of T cells in mESC-derived TEP-treated mice are rapidly restored after BMT.

Splenic T cells in the mESC-derived TEP-treated allo-BM transplant recipients are functional and have a diverse TCR repertoire. (A-C) Lethally irradiated C57BL/6 mice were injected intrathymically with mESC-derived EpCAM1+, EpCAM1− cells, or PBS, and intravenously with TCD-BM from BALB/c mice as in Figure 2. Thirty days after BMT, (A) splenocytes were stimulated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies, and cell proliferation was determined by [3H] thymidine incorporation. (B-C) Splenocytes were stimulated with phorbol myristate acetate and ionomycin and stained for cell surface markers and intercellular cytokines with the use of H-2d, CD4, CD8, IL-2, IFN-γ, and TNFα. The percentages of IL-2–, IFN-γ–, and TNFα-positive cells in donor origin CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were determined by flow cytometry. (D) Groups of BM transplant recipients were vaccinated with 50 μg of OVA emulsified in complete Freund adjuvant. Two weeks later, freshly isolated splenic CD3+ cells were cultured in the presence of irradiated normal splenocytes (from BALB/c mice) ± OVA for 4 days. T-cell proliferation was then determined by [3H] thymidine incorporation. (E) Lethally irradiated 129B6F2 mice were injected intrathymically with mESC-derived EpCAM1+ cells and intravenously with TCD BM from B6 mice. On day 60 after BMT, splenocytes were analyzed for the TCR Vβ families on donor origin CD3+ T cells by flow cytometry. Means ± SDs are presented (n = 5-6). ***P < .001. The data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

Splenic T cells in the mESC-derived TEP-treated allo-BM transplant recipients are functional and have a diverse TCR repertoire. (A-C) Lethally irradiated C57BL/6 mice were injected intrathymically with mESC-derived EpCAM1+, EpCAM1− cells, or PBS, and intravenously with TCD-BM from BALB/c mice as in Figure 2. Thirty days after BMT, (A) splenocytes were stimulated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies, and cell proliferation was determined by [3H] thymidine incorporation. (B-C) Splenocytes were stimulated with phorbol myristate acetate and ionomycin and stained for cell surface markers and intercellular cytokines with the use of H-2d, CD4, CD8, IL-2, IFN-γ, and TNFα. The percentages of IL-2–, IFN-γ–, and TNFα-positive cells in donor origin CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were determined by flow cytometry. (D) Groups of BM transplant recipients were vaccinated with 50 μg of OVA emulsified in complete Freund adjuvant. Two weeks later, freshly isolated splenic CD3+ cells were cultured in the presence of irradiated normal splenocytes (from BALB/c mice) ± OVA for 4 days. T-cell proliferation was then determined by [3H] thymidine incorporation. (E) Lethally irradiated 129B6F2 mice were injected intrathymically with mESC-derived EpCAM1+ cells and intravenously with TCD BM from B6 mice. On day 60 after BMT, splenocytes were analyzed for the TCR Vβ families on donor origin CD3+ T cells by flow cytometry. Means ± SDs are presented (n = 5-6). ***P < .001. The data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

We also evaluated the TCR repertoire of donor-origin T cells (from B6 mice) in EpCAM1+ cell–treated BMT 129B6F2 mice and found that these T cells had a diverse TCR repertoire (Figure 3E).

mESC-derived TEP-treated allo-BM transplant recipients do not induce GVHD but develop host and mESC tolerance

GVHD is a serious problem for patients after BMT. We evaluated whether GVHD occurs in mESC-derived TEP-treated allo-BM transplant recipients. As shown in Figure 4A-D, we did not observe any signs of GVHD in EpCAM1+ cell–treated BM transplant recipients as determined by mortality, weight loss, clinical GVHD score, and subclinical histopathologic analysis.

mESC-derived TEP-treated allo-BM transplant recipients do not develop GVHD but exhibit host and mESC tolerance. (A-E) Lethally irradiated C57BL/6 mice were injected intrathymically with mESC-derived EpCAM1+ cells and intravenously with TCD BM from BALB/c mice. Syngeneic BMT (both BM and recipients from 129SVEVTac mice) was used as controls. (A) Survival was monitored daily; (B) weights and (C) clinically GVHD scores were evaluated weekly; (D) histopathologic analysis of signs of GVHD in liver, small bowel (SB), and large bowel (LB) were performed on day 90 after BMT. (E) Lethally irradiated BALB/c were injected intrathymically with TC-1 mESC-derived EpCAM1+ cells and intravenously with TCD BM from CBA mice. (F) Lethally irradiated BALB/c were injected intrathymically with TC-1 mESC-derived EpCAM1+ cells and intravenously with TCD BM from BALB/c mice. (E-F) Ninety days later, splenocytes were harvested and used as effector cells for MLRs. Splenocytes from normal non-BMT CBA or BALB/c mice are used as controls. The effector cells were mixed with irradiated splenocytes (as stimulators) from BALB/c, 129SVETac, and CBA mice, respectively. Cell proliferation was determined by [3H]-thymidine incorporation. Data are shown as stimulation index. (E) Mean CPM in MLRs with splenocytes from BMT recipients or normal CBA mice as effectors and splenocytes from BALB/c, 129SVETac, and CBA mice as stimulators were 978, 979, 987, and 46 012, 29 861, and 1053, respectively. (F) Mean CPM in MLRs with splenocytes from BMT recipients or normal CBA mice as effectors and splenocytes from BALB/c, 129SVETac, and CBA mice as stimulators were 917, 945, 4775, and 971, 24 765, and 41 729, respectively. The data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

mESC-derived TEP-treated allo-BM transplant recipients do not develop GVHD but exhibit host and mESC tolerance. (A-E) Lethally irradiated C57BL/6 mice were injected intrathymically with mESC-derived EpCAM1+ cells and intravenously with TCD BM from BALB/c mice. Syngeneic BMT (both BM and recipients from 129SVEVTac mice) was used as controls. (A) Survival was monitored daily; (B) weights and (C) clinically GVHD scores were evaluated weekly; (D) histopathologic analysis of signs of GVHD in liver, small bowel (SB), and large bowel (LB) were performed on day 90 after BMT. (E) Lethally irradiated BALB/c were injected intrathymically with TC-1 mESC-derived EpCAM1+ cells and intravenously with TCD BM from CBA mice. (F) Lethally irradiated BALB/c were injected intrathymically with TC-1 mESC-derived EpCAM1+ cells and intravenously with TCD BM from BALB/c mice. (E-F) Ninety days later, splenocytes were harvested and used as effector cells for MLRs. Splenocytes from normal non-BMT CBA or BALB/c mice are used as controls. The effector cells were mixed with irradiated splenocytes (as stimulators) from BALB/c, 129SVETac, and CBA mice, respectively. Cell proliferation was determined by [3H]-thymidine incorporation. Data are shown as stimulation index. (E) Mean CPM in MLRs with splenocytes from BMT recipients or normal CBA mice as effectors and splenocytes from BALB/c, 129SVETac, and CBA mice as stimulators were 978, 979, 987, and 46 012, 29 861, and 1053, respectively. (F) Mean CPM in MLRs with splenocytes from BMT recipients or normal CBA mice as effectors and splenocytes from BALB/c, 129SVETac, and CBA mice as stimulators were 917, 945, 4775, and 971, 24 765, and 41 729, respectively. The data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

Studies have shown that TECs are involved in thymic negative selection in which potentially autoreactive T cells are deleted or inactivated.5 To determine whether T cells in these BM transplant recipients have developed immune tolerance to host and mESC antigens, we performed MLRs. Splenocytes from EpCAM1+ cell–treated allo-BM transplant recipients were used as effector cells, and irradiated splenocytes from donor (BM and mESCs) and host mouse stains were used as stimulators. As shown in Figure 4E and F, splenocytes from EpCAM1+–treated BM transplant recipients failed to proliferate in response to stimulation with cells from donor- and host-haplotypes, but they were able to mount an immune response to third-party antigens, suggesting that immune tolerance to host, mESC, and donor antigens had been established.

To further confirm that these allo-BM transplant recipients were immune tolerant to the mESC antigens, lethally irradiated BALB/c mice were injected intrathymically with mESC (H-2b)–derived EpCAM1+, EpCAM1− cells, or PBS, and intravenously with TCD BM from BALB/c mice. Three months after BMT, undifferentiated mESCs were transplanted under the kidney capsule of these BM transplant recipients. The formation of teratomas was then evaluated 4 weeks later. We found that teratomas developed in all EpCAM1+ cell–treated BM transplant recipients but not in any PBS-treated BM transplant recipients and normal non-BMT BALB/c mice (supplemental Table 1). Interestingly, 2 of the 7 EpCAM1− cell–treated BM transplant recipients also developed teratoma, suggesting mESC-derived antigens may be taken up by host dendritic cells, which results in negative selection of developing T cells. To determine whether these BM transplant recipients were tolerant to the mESC-derived tissues, we transplanted mESC-derived EBs that have spontaneously differentiated in vitro for 14 days. Identical results were obtained when differentiated mESCs were transplanted (supplemental Table 1). In all experiments, teratomas contained anatomical structures derived from each of the 3 embryonic germ layers with no signs of tissue damage or infiltration by leukocytes (supplemental Figure 3). Collectively, these data suggest that mESC-derived TEP-treated BM transplant recipients had developed tolerance to the mESCs and their derivatives.

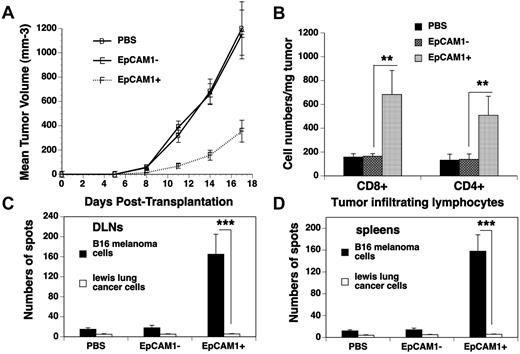

mESC-derived TEP treatment promotes GVT activity after allo-BMT

We hypothesized that enhanced T-cell function in EpCAM1+ cell–treated BMT mice could translate into increased GVT activity. To test this hypothesis, we injected B16F10 melanoma cells subcutaneously into mESC-derived cell–treated recipients at day 14 after BMT. A significant delay of local tumor growth was observed in EpCAM1+ cell–treated mice compared with that in EpCAM1− cell– or PBS-treated mice (Figure 5A). Because a high density of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes has been reported to be associated with a favorable outcome in tumor animal models and patients,26,27 we examined tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in these recipients on day 17 after tumor inoculation. As shown in Figure 5B, the numbers of donor-origin CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the tumors from EpCAM1+ cell–treated mice were 5- to 7-fold higher than those in the tumors from EpCAM1− cell– or PBS-treated mice. In addition to the tumors themselves, there was a parallel increase in the number of donor-origin CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the draining lymph node (DLN; data not shown). Therefore, GVT activity in mESC-derived TEP-treated allo-BM transplant recipients was augmented, which was associated with enhanced infiltration of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the tumors.

GVT activity is enhanced in mESC-derived TEP-treated BM transplant recipients. Lethally irradiated C57BL/6 mice were injected intrathymically with mESC-derived EpCAM1+, EpCAM1− cells, or PBS, and intravenously with 5 × 106 TCD BM from BALB/c mice. At day 14 after BMT, the recipients were injected subcutaneously with B16F10 melanoma cells. (A) The mean tumor volume (in mm3) ± SD are shown. (B-D) At day 17 after tumor injection, single-cell suspensions from (B) the tumors were analyzed for CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (mean cell number/mg of tumor ± SD); (C) DLNs and (D) spleens were cultured with irradiated B16F10 melanoma or Lewis lung cancer cells. ELISPOT assays were then performed for IFN-γ+ cells. Mean number of spots/1 × 105 T cells ± SD are presented (n = 5-6). **P < .01 and ***P < .001. The data are representative of 2 independent experiments.

GVT activity is enhanced in mESC-derived TEP-treated BM transplant recipients. Lethally irradiated C57BL/6 mice were injected intrathymically with mESC-derived EpCAM1+, EpCAM1− cells, or PBS, and intravenously with 5 × 106 TCD BM from BALB/c mice. At day 14 after BMT, the recipients were injected subcutaneously with B16F10 melanoma cells. (A) The mean tumor volume (in mm3) ± SD are shown. (B-D) At day 17 after tumor injection, single-cell suspensions from (B) the tumors were analyzed for CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (mean cell number/mg of tumor ± SD); (C) DLNs and (D) spleens were cultured with irradiated B16F10 melanoma or Lewis lung cancer cells. ELISPOT assays were then performed for IFN-γ+ cells. Mean number of spots/1 × 105 T cells ± SD are presented (n = 5-6). **P < .01 and ***P < .001. The data are representative of 2 independent experiments.

To determine whether tumor-specific immunologic responses were established in the melanoma-bearing mice, we examined the number of IFN-γ–producing cells from the DLNs and spleen after in vitro stimulation with syngeneic homologous or heterologous tumor cells (which served as specificity controls). As shown in Figure 5C, the numbers of IFN-γ–producing cells among the cultured DLN cells from day 17 B16F10 melanoma-bearing mice that had been transplanted with EpCAM1+ cells were 8- to 10-fold higher than those from EpCAM1− cell– or PBS-treated mice after in vitro stimulation with B16F10 cells. Identical results were obtained when splenocytes from these same animals were used (Figure 5D). However, no increase was observed in IFN-γ–producing cells in any of the cultures that were stimulated with lung cancer cells. These results suggest both regional and systemic tumor-specific immunologic responses have been established in EpCAM1+ cell–treated BM transplant recipients.

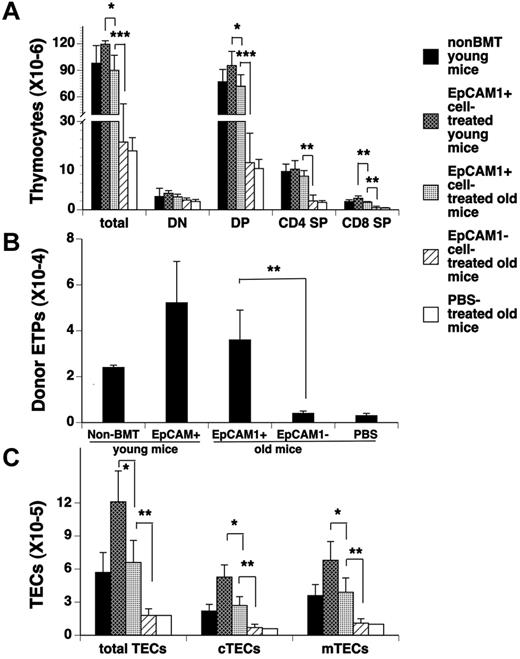

Transplantation of mESC-derived TEPs enhance thymopoiesis in old allo-BM transplant recipients

Aging has been associated with thymic involution that results in a decline in thymic output, so we wanted to determine the ability of EpCAM1+ mESC-derived TEPs to restore thymopoiesis in aged recipient mice. In these experiments, lethally irradiated 12- to 14-month-old 129B6F2 mice were injected intrathymically with mESC-derived EpCAM1+ or EpCAM1− cells, or PBS, and intravenously with TCD BM from 1-month-old BALB/c mice. As a control, lethally irradiated 1-month-old 129B6F2 mice were injected intrathymically with mESC-derived EpCAM1+ cells and intravenously with TCD BM from 1-month-old BALB/c mice. As shown in Figure 6A through C, at day 30 after BMT the numbers of thymocytes and TECs and their subsets (including ETPs) in EpCAM1+ cell–treated aged mice were significantly increased to the levels observed in normal non-BMT young mice, and 4- to 6-fold higher than those in EpCAM1− cell–, or PBS-treated aged mice. Again, EpCAM1+ cell treatment in aged mice significantly increased the numbers of total and naive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the spleen (data not shown). Therefore, injection of mESC-derived TEPs can also enhance thymopoiesis and naive T-cell regeneration in aged allo-BM transplant recipients. However, the numbers of thymocytes and their subsets in EpCAM1+ cell–treated young mice were higher than those in EpCAM1+ cell–treated aged mice (Figure 6A), which, at least in part, was because of enhanced generation of TECs from mESC-derived TEPs in the young thymus (Figure 6C).

Transplantation of mESC-derived TEPs improves thymic reconstitution in aged allo-BM transplant recipients. Lethally irradiated 12- to 14-month-old or 1-month-old 129B6F2 mice were injected intrathymically with mESC-derived EpCAM1+, EpCAM1− cells, or PBS, and intravenously with TCD BM from BALB/c mice. Thirty days after BMT, the numbers of (A) total thymocytes and their subsets, (B) donor-origin ETPs (lin−IL-7Rα −c-Kit+CD44+CD25−), and (C) total TECs (CD45−EpCAM1+MHC II+) and their subsets cTECs (CD45−EpCAM1+MHC II+Ly51+) and mTECs (CD45−EpCAM1+MHC II+Ly51−) were quantified by flow cytometry and compared with those in non-BMT control or EpCAM1+ cell–treated BMT young mice. Means ± SDs are presented (n = 5-6). Mean percentages of donor-origin thymocytes in mESC-derived EpCAM1+ cell–, EpCAM1− cell–, or PBS-treated BMT aged mice and EpCAM1+ cell–treated young mice are 86.9%, 87.2%, 87.7%, and 85.9%, respectively. **P < .01 and ***P < .001. The data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

Transplantation of mESC-derived TEPs improves thymic reconstitution in aged allo-BM transplant recipients. Lethally irradiated 12- to 14-month-old or 1-month-old 129B6F2 mice were injected intrathymically with mESC-derived EpCAM1+, EpCAM1− cells, or PBS, and intravenously with TCD BM from BALB/c mice. Thirty days after BMT, the numbers of (A) total thymocytes and their subsets, (B) donor-origin ETPs (lin−IL-7Rα −c-Kit+CD44+CD25−), and (C) total TECs (CD45−EpCAM1+MHC II+) and their subsets cTECs (CD45−EpCAM1+MHC II+Ly51+) and mTECs (CD45−EpCAM1+MHC II+Ly51−) were quantified by flow cytometry and compared with those in non-BMT control or EpCAM1+ cell–treated BMT young mice. Means ± SDs are presented (n = 5-6). Mean percentages of donor-origin thymocytes in mESC-derived EpCAM1+ cell–, EpCAM1− cell–, or PBS-treated BMT aged mice and EpCAM1+ cell–treated young mice are 86.9%, 87.2%, 87.7%, and 85.9%, respectively. **P < .01 and ***P < .001. The data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

mESC-derived TEPs, when injected subcutaneously, enhance T-cell regeneration in nude mice

Because subcutaneous transplantation of thymus tissues has been successfully used to generate T cells in animals and human patients,15,28-30 we next wanted to determine whether subcutaneous injection of mESC-derived TEPs could also enhance T-cell regeneration. To this end, the reaggregates of mESC-EpCAM1+ or EpCAM1− cells and immature thymocytes (CD4−CD8−CD45+) were transplanted subcutaneously into 1-month-old nude mice. Three months later, we evaluated T cells in lymph nodes and found that the numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ cells in EpCAM1+ cell–treated nude mice were ∼ 8-fold above those in EpCAM1− cell–treated nude mice or control untreated nude mice (Table 1). With the use of immature thymocytes from eGFP+ transgenic mice, we found that a mean of 64% CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were derived from the initial grafts. The other CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells may be derived from host BM T-cell progenitors that were recruited into and developed in the grafts. Furthermore, the T cells from EpCAM1+ cell–treated nude mice had a normal proliferative response to TCR stimulation, comparable to that seen in normal wild-type mice (data not shown). These results suggest that mESC-derived TEPs injected subcutaneously can also differentiate into TECs that can support T-cell development.

Analysis of T cell number in lymph nodes from grafted nude recipients

| Graft . | CD4+ cells (± SD × 105) . | CD8+ cells (± SD × 105) . |

|---|---|---|

| mESC-EpCAM1+ cells | 12.9 ± 1.4* | 8.2 ± 0.7* |

| mESC-EpCAM1− cells | 1.6 ± 0.4 | 1.0 ± 0.2 |

| Ungrafted nude | 1.5 ± 0.5 | 0.9 ± 0.1 |

| Graft . | CD4+ cells (± SD × 105) . | CD8+ cells (± SD × 105) . |

|---|---|---|

| mESC-EpCAM1+ cells | 12.9 ± 1.4* | 8.2 ± 0.7* |

| mESC-EpCAM1− cells | 1.6 ± 0.4 | 1.0 ± 0.2 |

| Ungrafted nude | 1.5 ± 0.5 | 0.9 ± 0.1 |

P < .01 compared with mESC-EpCAM1− cells.

Discussion

It is well known that the thymus undergoes age-dependent involution resulting in decreased numbers, TCR diversity, and functional capacities of T cells in the elderly.3,9 Age-dependent thymic involution contributes to increased incidences of infections, autoimmunity, and cancers in the elderly. The effect of thymic involution is even more significant when there is a need to regenerate the T-cell compartment, as in patients who receive a BM transplant.31 Studies have shown that transferring young BM into aged recipients does not restore the thymic architecture to that of a young thymus; aged recipients still have diminished thymocyte numbers as well as significantly reduced numbers of naive peripheral T cells compared with young recipients. These results suggest that there are some irreversible aspects within the aged thymic microenvironment.3 This notion is supported by reports that TECs undergo a qualitative and quantitative loss during aging.3,4 We show here that transplantation of mESC-derived TEPs can significantly enhance thymopoiesis and the numbers of naive peripheral T cells in aged BM transplant recipients. When combined with our previous data showing that mESC-derived TEPs, when transferred in vivo, differentiated into both types of TECs and reconstituted normal thymic architecture,10 our results suggest that mESC-derived TECs can restore the aged thymic microenvironment.

We observed no signs of GVHD in the mESC-derived TEP-treated allo-BM transplant recipients. Furthermore, these recipients developed immune tolerance to host and mESC-derived cells. Many studies have suggested that ESCs offer enormous potential for treating a variety of degenerative diseases because of their ability to differentiate into many types of cells.32 However, one of the main challenges in ESC-based therapies is that ESC-derived tissues can be rejected by the host immune system. Although ESCs are reportedly immune privileged,33,34 several studies have shown that ESC-derived cells can be rejected by the host even if all MHC molecules are the same, and only minor histocompatibility antigens differ.35-37 Therefore, strategies to induce tolerance to ESC-based transplants are required. Currently, tolerance to foreign grafts relies on inhibiting preexisting host T cells with the use of immunosuppressive drugs. Despite achieving some success, immunosuppressive strategies have limitations that include a difficulty in achieving long-term tolerance and the development of immune deficiency that can result in increased risk of tumor relapse and high rates of opportunistic infections.31 Therefore, strategies to induce donor-specific tolerance in the host, while maintaining generalized immunocompetence, are required.

The most logical way to induce donor-specific tolerance in allo-BM transplant recipients would be to use the same central tolerance mechanisms that occur normally in the thymus, which prevent the immune system from rejecting self cells and tissues. To achieve this tolerance, the thymus has to be sufficiently functional, and the graft antigens have to be present in the thymus.31,38,39 However, as mentioned earlier, the thymus undergoes age-dependent involution, and its functions are seriously compromised in the elderly. Although transplantation of donor thymus fragments or thymic epithelium in patients and experimental animals has been successfully used as a method for the induction of tolerance in transplantation of tissue grafts of the thymus haplotype,15,28-30 application has been restricted by the limited availability of thymic tissue. Our approach of transplantation of ESC-derived TEPs not only improves thymic function but also incorporates donor ESC antigens into the thymus, thereby providing a powerful tool to prevent rejection of the ESC-derived tissues.

The mechanisms by which the injection of mESC-derived TEPs induces tolerance to mESC antigens may include negative selection directly mediated by mESC-derived TECs.5 However, 2 of the 7 EpCAM1− cell–treated BM transplant recipients also developed tolerance, suggesting that host thymic dendritic cells may also take up mESC antigens and mediate negative selection. In addition, the generation of Tregs supported by mESC-derived TECs may also play a role in the maintenance of peripheral immune tolerance.40,41

Although GVHD was not induced in our study, GVT activity was enhanced and tumor-specific immunologic responses were established. Because IFN-γ has been shown to enhance GVT activity while inhibiting GVHD in allo-BM transplant recipients,42-45 the increased production of IFN-γ in T cells from mESC-derived TEP-treated BM transplant recipients may play an important role in the enhanced GVT activity. It is possible that a broad TCR repertoire in donor-origin T cells of these recipients also contributes to enhanced antitumor immunity through recognition of a variety of foreign antigens, including tumor-specific antigens.46 It is well known that Tregs can inhibit antitumor immunity. Although the number of Tregs was increased in mESC-derived TEP-treated BMT mice, the GVT activity was maintained. Therefore, Tregs in these mice may have antigen specificity, in that they are only specific for antigens encountered in the thymus and not for tumor-specific antigens. Our results are consistent with previous reports that donor Tregs can suppress GVHD while allowing GVT.47-50

We observed that subcutaneous injection of mESC-derived TEPs had similar effects as intrathymic injection. It is important because subcutaneous injection is more practical than intrathymic injection for future use in human patients. In addition, no tumor formation was seen in any of the recipients of mESC-derived TEPs which probably was because these cells had been differentiated and separated from the undifferentiated mESCs.

In summary, we have demonstrated that transplantation of mESC-derived TEPs can efficiently restore thymopoiesis and naive T-cell generation in both young and old allo-BM transplant recipients. GVHD was not induced, whereas GVT was increased. Furthermore, allo-BM transplant recipients developed immune tolerance to host and mESC-derived cells. Thus, ESC-derived TEPs not only hold considerable promise clinically for preventing or reversing T-cell deficiency after BMT, they also provide a powerful tool to induce immune tolerance to ESC-derived cell and tissue transplants. In addition, ESC-derived TEPs may also have use as a means to reverse age-dependent thymic involution, thereby enhancing immune function and decreasing infection rates in the elderly.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Connecticut Stem Cell Research Program (grant 08-SCA-UCHC-009, L.L.), the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (grant 2008J0077, Q.Z. and M.Y.), and the National Basic Research Program of China (973 program, grant 2010CB945301, Y.Z.).

Authorship

Contribution: L.L. designed and performed experiments, analyzed data, supervised the study, and wrote the manuscript; C.C., J.J., and Z.H. performed experiments and analyzed data; Q.Z. performed experiments and analyzed data; M.Y. analyzed data; R.B. designed experiments and edited the manuscript; and Y.Z. designed experiments, analyzed data, and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for L.L. is Department of Allied Health Sciences, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT.

Correspondence: Laijun Lai, University of Connecticut Health Center, Department of Immunology, 263 Farmington Ave, Farmington, CT 06030; e-mail: llai@neuron.uchc.edu.

![Figure 3. Splenic T cells in the mESC-derived TEP-treated allo-BM transplant recipients are functional and have a diverse TCR repertoire. (A-C) Lethally irradiated C57BL/6 mice were injected intrathymically with mESC-derived EpCAM1+, EpCAM1− cells, or PBS, and intravenously with TCD-BM from BALB/c mice as in Figure 2. Thirty days after BMT, (A) splenocytes were stimulated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies, and cell proliferation was determined by [3H] thymidine incorporation. (B-C) Splenocytes were stimulated with phorbol myristate acetate and ionomycin and stained for cell surface markers and intercellular cytokines with the use of H-2d, CD4, CD8, IL-2, IFN-γ, and TNFα. The percentages of IL-2–, IFN-γ–, and TNFα-positive cells in donor origin CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were determined by flow cytometry. (D) Groups of BM transplant recipients were vaccinated with 50 μg of OVA emulsified in complete Freund adjuvant. Two weeks later, freshly isolated splenic CD3+ cells were cultured in the presence of irradiated normal splenocytes (from BALB/c mice) ± OVA for 4 days. T-cell proliferation was then determined by [3H] thymidine incorporation. (E) Lethally irradiated 129B6F2 mice were injected intrathymically with mESC-derived EpCAM1+ cells and intravenously with TCD BM from B6 mice. On day 60 after BMT, splenocytes were analyzed for the TCR Vβ families on donor origin CD3+ T cells by flow cytometry. Means ± SDs are presented (n = 5-6). ***P < .001. The data are representative of 3 independent experiments.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/118/12/10.1182_blood-2011-03-340794/4/m_zh89991178310003.jpeg?Expires=1770974196&Signature=dqx1u1Wd6B~231afDRI-XF6fqgQrf7qYdnDVatYlCHiktm79FtVnDrzm9Yx1QcMve1n0zRnZu4s4ImAnKSGdY-Y4SBHvrtH3eBTHJhCJ23wxK53iVp8wb9B~h-0W3070FRPlyLJs76o~f-qw6BWYMuNezl4jxh53O76ulo00hfG0Dxw3KTQovqHf0vYWoUbKtm3DmMbwPyzB0vekcK2GcuyXcKG8xkl3r2j~~ZOAaf5v7-Z14ZgpBQJsuTHW10hpd~Douf1hbTUeJq38rf5xg-yfMqj8YRgFwkLY5~IEJoiJqb1aFqoZOrcj4vLR-K8mGtE8ZAxb2RKo65TMgmqswQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 4. mESC-derived TEP-treated allo-BM transplant recipients do not develop GVHD but exhibit host and mESC tolerance. (A-E) Lethally irradiated C57BL/6 mice were injected intrathymically with mESC-derived EpCAM1+ cells and intravenously with TCD BM from BALB/c mice. Syngeneic BMT (both BM and recipients from 129SVEVTac mice) was used as controls. (A) Survival was monitored daily; (B) weights and (C) clinically GVHD scores were evaluated weekly; (D) histopathologic analysis of signs of GVHD in liver, small bowel (SB), and large bowel (LB) were performed on day 90 after BMT. (E) Lethally irradiated BALB/c were injected intrathymically with TC-1 mESC-derived EpCAM1+ cells and intravenously with TCD BM from CBA mice. (F) Lethally irradiated BALB/c were injected intrathymically with TC-1 mESC-derived EpCAM1+ cells and intravenously with TCD BM from BALB/c mice. (E-F) Ninety days later, splenocytes were harvested and used as effector cells for MLRs. Splenocytes from normal non-BMT CBA or BALB/c mice are used as controls. The effector cells were mixed with irradiated splenocytes (as stimulators) from BALB/c, 129SVETac, and CBA mice, respectively. Cell proliferation was determined by [3H]-thymidine incorporation. Data are shown as stimulation index. (E) Mean CPM in MLRs with splenocytes from BMT recipients or normal CBA mice as effectors and splenocytes from BALB/c, 129SVETac, and CBA mice as stimulators were 978, 979, 987, and 46 012, 29 861, and 1053, respectively. (F) Mean CPM in MLRs with splenocytes from BMT recipients or normal CBA mice as effectors and splenocytes from BALB/c, 129SVETac, and CBA mice as stimulators were 917, 945, 4775, and 971, 24 765, and 41 729, respectively. The data are representative of 3 independent experiments.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/118/12/10.1182_blood-2011-03-340794/4/m_zh89991178310004.jpeg?Expires=1770974196&Signature=hDKD1HM4b1-DCjbzQiTNQqW5NkcKb0uyCW57Eqp5M83IxVZ1cI2J9qkmq7-eb0KrVg3Dj3tUQiXiOSCzKIu3Pf19fbQNUNy2g526UfwI96Y3fAo5tBjZxrxsmqpHp2~6L7WUTprcqEySS4CG5VWz1e6wZqnEUMTeNI5ukuzdqnOvkxJ2TelwUYx2ewC91c9sHvgHmBmjiiwTFXcjRHg2qGj74oSMG80tHsu8ckw-xn-b6P-31jkIV-xT7joMx6sRax~XgwCExKnO35yszErP09Jiqhj3B3dluCEl7vBhiIgpo2Y31eow9xl0ZuQWoN-HI1Y3jHOHjuQZLNLJi~pw8g__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal