Abstract

Paratarg-7, a frequent autoantigenic target, and all other autoantigenic targets of human paraproteins molecularly defined to date are hyperphosphorylated in the respective patients compared with healthy controls, suggesting that hyperphosphorylation of autoantigenic paraprotein targets is a general mechanism underlying the pathogenesis of these paraproteins. We now show that hyperphosphorylation of paratarg-7 occurs because of an additional phosphorylation of Ser17, which is located within the paraprotein-binding epitope. Coimmunoprecipitation identified phosphokinase C ζ (PKCζ) as the kinase responsible for the phosphorylation of most, and phosphatase 2A (PP2A) as the phosphatase responsible for the dephosphorylation of all hyperphosphorylated autoantigenic targets of paraproteins. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) or mutations of PKCζ and PP2A were excluded. However, PP2A was inactivated by phosphorylation of its catalytic subunit at Y307. Stimulation of T cells from healthy carriers of wild-type paratarg-7 induced a partial and transient hyperphosphorylation between days 4 and 18, which was maintained by incubation with inhibitors of PP2A, again indicating that an inactivation of PP2A is responsible for the hyperphosphorylation of autoantigenic paraprotein targets. We conclude that the genetic defect underlying the dominantly inherited hyperphosphorylation of autoantigenic paraprotein targets is not in the PP2A itself, but in genes or proteins controlling PP2A activity by phosphorylation of its catalytic subunit.

Introduction

Antigenic targets of paraproteins from patients with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS), multiple myeloma (MM), and Waldenström macroglobulinemia (WM) might play a role in the pathogenesis of these neoplasms; however, only few have been identified to date. We recently demonstrated that paratarg-7 is the target of ∼ 15% of paraproteins of the IgA and IgG type from patients with MGUS and MM,1 and 11% of IgM-MGUS and WM.2 All patients with paratarg-7–specific paraproteins are carriers of a hyperphosphorylated modification of paratarg-7 (pP-7),3 and the pP7-carrier state is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion.4 Because only 2% of the healthy European population are pP-7 carriers, paratarg-7 is the strongest risk factor for IgG/IgA-MGUS and MM (relative risk 7.9)3 and IgM-MGUS and WM (relative risk 6.2),2 and the first dominantly inherited risk factor for any hematologic neoplasias to date. Although the prevalence of the pP7 carrier state is lower among Japanese patients with IgA/IgG MGUS and MM and healthy Japanese controls, the relative risk for a Japanese carrier of pP7 to develop IgA/IgG MGUS and MM is also very high (13.8).5 The dominant inheritance of pP-7 explains cases of familial MGUS/MM. Recently, we showed that the paraproteins of all affected members of another previously reported family with 6 cases affected with MGUS/MM6 did not bind to paratarg-7, but all of them were directed against a newly defined autoantigen that we designated paratarg-8. The paraproteins of affected members of all 4 families with familial MGUS/MM that we could study so far targeted family typical Ags.7 All patients with a paratarg-8–specific paraprotein were carriers of a hyperphosphorylated modification of paratarg-8 (pP-8). Apart from the affected members of this index family, however, prevalence of pP-8 was rare: we found only 1 of 300 MGUS/MM patients with a paratarg-8–specific paraprotein (who was also carrier of pP-8) and only 1 of 200 healthy European controls was a carrier of pP-8.7 With paratarg-7 and paratarg-8 representing hyperphosphorylated autoantigenic paraproteins targets, we rechecked the phosphorylation state of all autoantigenic paraprotein targets molecularly defined by us to date and found that all 8 of 8 autoantigenic paraproteins were hyperphosphorylated in the respective patients compared with the respective autoantigens in healthy controls,7 demonstrating that hyperphosphorylation of autoantigenic targets of paraproteins is a consistent finding and might represent a general mechanism in the pathogenesis of MGUS/MM/WM. Interestingly, only the autoantigen targeted by the paraparotein of the respective patient was found to be hyperphosphorylated in the cells of this patient, while autoantigens targeted by the paraproteins of other patients were not. The aim of the current study was the identification of the kinases and phosphatases responsible for the maintenance of the hyperphosphorylated state. Surprisingly, we found that the same phosphatase is involved in the hyperphosphorylation of all autoantigenic paraproteins targets molecularly defined to date.

Methods

Patients and controls

The study was approved by the local ethical review board (Ethikkommission der Ärztekammer des Saarlandes) and conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Recombinant DNA work was performed with permission and according to the regulations of local authorities (government of the state Saarland, Federal Republic of Germany). Human materials were obtained during routine diagnostic or therapeutic procedures and stored at −80°C. Written informed consent was obtained from patients and controls for studying paratarg-7 in lysates of their whole peripheral blood.

Lymphoblastoid cell lines

Lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs) were established by infection of PBMCs with EBV as described before.8

Inhibitory experiments

Stably transfected lymphoblastoid cell lines were cultured in the presence of inhibitory compounds as indicated. After 5 days, cells were removed and analyzed by isoelectric focusing (IEF) and immunoblot detection.

Isoelectric focusing

Washed LCLs were treated with lysis buffer (8M urea, 0.1M NaH2PO4, 0.01M Tris HCl, 0.1% NP40), mixed with 2× IEF loading buffer and subjected to isoelectric focusing using precast gels (Invitrogen; IEF pH 3-10). Analysis was done according to the manufacturer's protocol (1 hour 100 V, 1 hour 200 V, and 30 minutes 500 V). After semi-dry blotting on PVDF membranes (450 mA, 1 hour), immunodetection was done using patients' or control serum. The membrane was blocked in TST/milk buffer (10% milk in 10mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.5, 150mM NaCl, 0.1% [v/v] Tween 20) overnight, washed, and incubated for 1 hour with serum in TST (paraprotein-containing patient's serum at a dilution of 1:108 and control patients serum at a dilution of 1:103). After 3 washings in TST, the membranes were incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with goat anti–human IgG POX-coupled Ab (Dianova) diluted 1:5000 in TST, subsequently washed in TST followed by ECL development.

Enzymatic treatment

LCLs were washed 3 times with PBS followed by lysis in LS buffer (10mM Tris HCl pH 8, 30 minutes 4°C). After increasing the concentration of Tris HCl to 100mM, alkaline phosphatase was added (1 U/μL per 500 μL of lysate) and incubated at 37°C overnight. The phosphatase was inactivated by heating at 80°C for 10 minutes. Equal volumes of sample and loading buffer were mixed, followed by IEF and immunodetection. For cleaving pP-7 by endopeptidases, LCLs were washed 3 times with PBS followed by lysis in LS buffer (10mM Tris HCl pH 8, 30 minutes 4°C). After changing to 100mM Tris HCl/10mM CaCl2, chymotrypsin was incubated overnight at room temperature, and trypsin at 37°C. PBS without enzymes was used as control. Incubation was stopped by the addition of 2mM PMSF. Endopeptidase-treated samples and controls were then submitted IEF followed by immunoblotting.

Paratarg-7 deletion mutants

Paratarg-7 fragments were obtained by PCR amplification using suitable primers and verified by sequencing. These fragments were subcloned into the vector and expressed as described before.1

Site-directed mutagenesis

Using the QuikChange II Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene) and a paratarg-7 DNA fragment coding for FLAG-tagged aa 1 to 60, mutants were constructed in which the serines were changed to alanines (Ser17Ala, Ser21Ala, and Ser17AlaSer21Ala). These mutants were stably transfected into HEK293 cells. Fragments of paratarg-7 were amplified by PCR using the primers listed below and full-length paratarg-7 as template followed by cloning into pSfi-FLAG as expression vector: SLP2-Start-DraI 5′-TTT AAA ATG CTG GCG CGC GCG GCG-3′; SLP2-Ende-DraI 5′-TTT AAA ACT CAT CTT GAC TCG ATC-3′; SLP2-aa62-DraI-as 5′-TTT AAA ACC AGG CTC CAG GAT CCG GTG-3′; SLP2-aa25-DraI-as 5′-TTT AAA CGG AGC GCG GCC AGA AGC-3′; and SLP2-aa26-DraI-s 5′-TTT AAA ATG CGC CGC GCC TCC TCT GGA-3′.

Complementation assay

Total lysates of HEK cells expressing FLAG-tagged paratarg-7 fragments were prepared and inactivated by heating (“acceptor lysate”). Cells of healthy donors or patients were lysed with 10mM Tris pH 8 and centrifuged (“donor lysate”). Both lysates were coincubated for 48 hours at 37°C and analyzed by IEF and immunodetection using anti-FLAG mAb.

Immunoprecipitation

Cell lysates were incubated with the first Ab at 4°C overnight. Ag-Ab complexes were purified by protein-G chromatography, followed by gel electrophoresis and blotting. Immunostaining was done using a second Ab. For details of the Abs, see the figure legends.

Quantitative PCR

LCLs from patients and healthy donors were used for the isolation of total RNA (Qiagen RNeasy Blood Kit). Reverse transcription was performed using Superscript II (Invitrogen) and oligo-dT primers according to the suppliers manual. Quantitative PCR was done on a Roche Lightcycler I using SYBR green and gene-specific primers. Gene copy number quantification was done as described previously.9,10

Results

Paratarg-7 in LCLs

In MGUS/MM/WM patients with a paratarg-7–specific paraprotein and healthy carriers of hyperphosphorylated paratarg-7 (pP-7), pP-7 was hyperphosphorylated constitutively in lysates of whole peripheral blood, erythrocytes, neutrophils, and lymphocytes, but also in EBV-transformed LCLs derived from these patients. This allowed for the use of these LCLs as an unlimited cellular source for the experiments of this study.

Identification of the phosphorylation site responsible for the hyperphosphorylation of paratarg-7

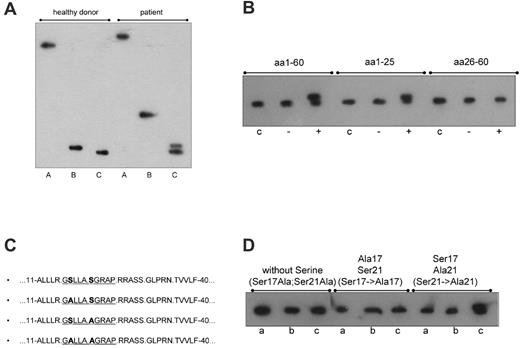

To narrow down the location of the additional hyperphosphorylation(s), paratarg-7 was digested with trypsin and chymotrypsin. Digestion with chymotrypsin results in a fragment containing aa 1 to 40 (http://db.systemsbiology.net:8080/proteomicsToolkit/proteinDigest.html). Comparing patients and controls, the additional phosphorylation was assigned to the fragment containing aa 1 to 40, which covers the region to which the patients' paraproteins bind. This was indicated by a modified migration of the immunopositive chymotryptic fragment and an additional immunoreactive band in the tryptic digest of paratarg-7 derived from erythrocytes and separated by IEF (Figure 1A).

Identification of the phosphorylation site responsible for the hyperphosphorylation of paratarg-7. (A) Immunoelectrophoretic focusing after endopeptidase treatment of paratarg-7. IEF separation followed by immunodetection with anti-paratarg-7 resulted in an additional band of the patient's LCL lysate after trypsin treatment (C) and a modified migration of the chymotryptic fragment (B). The differences in migration of the immunopositive fragments in lanes B and C indicate a different electric charge of the fragments that are the result of the additional phosphorylation. Lane A indicates LCL lysate; lane B, LCL lysate incubated with chymotrypsin; and lane C, LCL lysate incubated with trypsin. (B) Identification of the phosphorylation site responsible for the hyperphosphorylation of paratarg-7 in patients with paratarg-7– specific paraproteins. A phosphorylation site located between aa 1 to 25 is responsible for the hyperphosphorylation of paratarg-7. Lane c indicates recombinant fragment without complementation as control; lane –, recombinant fragment incubated with an enzyme mix from LCLs of a healthy donor carrying wild-type paratarg-7; and lane +, recombinant fragment incubated with an enzyme mix derived from LCLs of a patient carrying hyperphosphorylated paratarg-7. (C) Mutagenization of paratarg-7 fragments containing aa 1 to 62. (D) Isoelectric focusing of the respective fragments shown in panel C. Only the fragment containing Ser17 shows the additional band representing the hyperphosphorylated peptide after complementation with an enzyme mix derived from a carrier of hyperphosphorylated paratarg-7. Lane a indicates expression of the mutagenized fragment as control; lane b, incubation with a native lysate of LCLs from a healthy donor carrying wild-type paratarg-7; and lane c, incubation with a native lysate of LCLs derived from a patient carrying hyperphosphorylated paratarg-7.

Identification of the phosphorylation site responsible for the hyperphosphorylation of paratarg-7. (A) Immunoelectrophoretic focusing after endopeptidase treatment of paratarg-7. IEF separation followed by immunodetection with anti-paratarg-7 resulted in an additional band of the patient's LCL lysate after trypsin treatment (C) and a modified migration of the chymotryptic fragment (B). The differences in migration of the immunopositive fragments in lanes B and C indicate a different electric charge of the fragments that are the result of the additional phosphorylation. Lane A indicates LCL lysate; lane B, LCL lysate incubated with chymotrypsin; and lane C, LCL lysate incubated with trypsin. (B) Identification of the phosphorylation site responsible for the hyperphosphorylation of paratarg-7 in patients with paratarg-7– specific paraproteins. A phosphorylation site located between aa 1 to 25 is responsible for the hyperphosphorylation of paratarg-7. Lane c indicates recombinant fragment without complementation as control; lane –, recombinant fragment incubated with an enzyme mix from LCLs of a healthy donor carrying wild-type paratarg-7; and lane +, recombinant fragment incubated with an enzyme mix derived from LCLs of a patient carrying hyperphosphorylated paratarg-7. (C) Mutagenization of paratarg-7 fragments containing aa 1 to 62. (D) Isoelectric focusing of the respective fragments shown in panel C. Only the fragment containing Ser17 shows the additional band representing the hyperphosphorylated peptide after complementation with an enzyme mix derived from a carrier of hyperphosphorylated paratarg-7. Lane a indicates expression of the mutagenized fragment as control; lane b, incubation with a native lysate of LCLs from a healthy donor carrying wild-type paratarg-7; and lane c, incubation with a native lysate of LCLs derived from a patient carrying hyperphosphorylated paratarg-7.

As shown previously, the immunogenic region of paratarg-7 was identified as a region spanning 15 aa (H2N-SLLASGRAPRRASSG-COOH) near the N-terminal end of the protein.1 In further ELISA experiments with smaller overlapping paratarg7–derived peptides, the region spanning the epitope was narrowed down to a peptide spanning from aa 16 to 25 (data not shown). In addition, isoelectric focusing showed that a chymotryptic fragment of paratarg-7 (aa 1-40) derived from patients was hyperphosphorylated compared with the corresponding fragment of healthy donors. This was also shown for recombinant fragments containing aa 1 to 60 and aa 1 to 25, while no hyperphosphorylation was demonstrated in a fragment containing aa 20 to 60 (Figure 1B). Taken together, these findings demonstrate that aa 1 to 25 cover the paraprotein-binding epitope and the phosphorylation site that is responsible for the hyperphosphorylation of paratarg-7. This region contains 2 serines, 1 at position 17 and 1 at position 21. By site-directed mutagenesis of Ser17 and Ser21 to Ala17 and Ala21, respectively, followed by expression of these recombinant fragments and complementation assays using enzyme extracts derived from patients and healthy controls, Ser17 was identified as the site where hyperphosphorylation occurs (Figure 1C-D). Tyr124, another phosphorylation site described before by Rush et al,11 showed no difference between patients and healthy controls and was therefore excluded as being responsible for paratarg-7 hyperphosphorylation in the patients with paratarg7–specific paraproteins.

Identification of the kinase responsible for hyperphosphorylation of paratarg-7 in patients carrying hyperphosphorylated paratarg-7

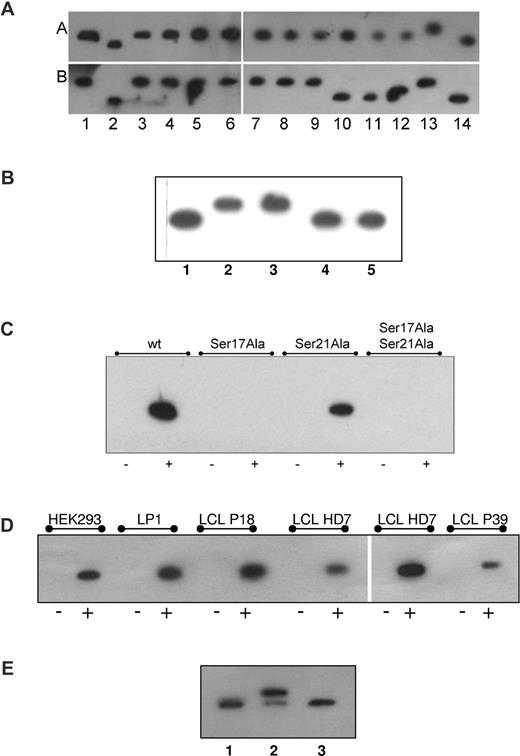

Hyperphosphorylation of paratarg-7 can be induced in PBMCs and LCLs derived from carriers of wild-type paratarg-7. This was shown by culturing LCLs derived from carriers of wild-type paratarg-7 in the presence of kinases or phosphatase inhibitors.12 The identification of Ser17 as the differential phosphorylation site led to the prediction of a phosphokinase C (PKC) responsible for hyperphosphorylation (www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/NetPhos/). IEF of wild-type LCLs in the presence of suitable inhibitors (staurosporine, wortmannin, bisindolylmaleimid I)12 identified the PKCζ isoform as the active kinase (Figure 2A). This was confirmed using highly specific PKCζ pseudosubstrate as inhibitor13 (Figure 2B). In addition, direct interaction of paratarg-7 and PKCζ was demonstrated by coimmunoprecipitation experiments using LCLs (Figures 2D and 3 lanes e-f). Finally, the direct interaction between PKCζ and Ser17 of paratarg-7 was demonstrated by coimmunoprecipitation (Figure 2C) of mutagenized peptide fragments as well as in in vitro experiments using purified PKCζ and paratarg-7 (Figure 2E).

Identification of the kinase responsible for the hyperphosphorylation of paratarg-7. (A) Inhibition of kinases. LCLs derived from a healthy donor carrying wild-type paratarg-7 (row A) or a patient carrying hyperphosphorylated paratarg-7 (row B) were cultured in the presence of inhibitors (dissolved in DMSO) at the indicated concentrations. Lysates were analyzed by IEF and stained with anti-paratarg-7. Lane 1 indicates LCLs from healthy donor and patient, respectively, cultured with addition of DMSO (1:106) only. Hyperphosphorylation was inhibited by incubation with staurosporine (2.5μM, lane 2), ellagic acid (10μM, lane 10), and wortmannin (5nM, lane 11). No effect was observed by incubation with, lanes 3 to 9: H89 (50nM), Akt1,2 inhibitor (200nM), purvalanol (100nM), SL327 (200nM), SP600125 (100nM), SB202190 (50nM), and ZM447439 (1μM). As controls, lysates of healthy donor (lane 12), patient (lane 13), and recombinant paratarg-7 in Escherichia coli (lane 14) were also analyzed. Panel A is composed of 4 separate IEF gels. (B) Inhibition of paratarg-7 hyperphosphorylation by PKCζ pseudosubstrate in LCL derived from patients with pP-7. IEF followed by immunodetection of paratarg-7 in LCLs derived from healthy donor (lane 1) and from a patient (lane 2) as control. LCLs derived from a patient with pP-7 were cultured without inhibitors (lane 3) or in the presence of bisindolylmaleimide I (6μM, lane 4) or PKCζ pseudosubstrate (50μM, lane 5). (C) Demonstration of the direct interaction of Ser17 of paratarg-7 with PKCζ: only mutated fragments containing Ser17 interact with PKCζ. No interaction was detected when Ser was replaced by Ala. wt indicates unmutated paratarg-7 fragment spanning aa 1 to 60; Ser17Ala, fragment spanning aa 1 to 60 with Ser17 replaced by Ala; Ser21Ala, fragment spanning aa 1 to 60 with Ser21 replaced by Ala; Ser17Ala Ser21Ala, fragment spanning aa 1 to 60 with both serines replaced by Ala; –, control (carrier of wild-type paratarg-7 wtP-7); +, carrier of hyperphosphorylated paratarg-7 pP-7. (D) Coimmunoprecipitation of paratarg-7 and PKCζ in cell lines (HEK293, LP1) and LCLs derived from patients (P18, P39) and healthy donor (HD7). In the left portion of the panel, precipitation of the complex was done using anti-STOML2 (BD Biosciences) followed by detection of PKCζ in the redissolved precipitate using anti-PKCζ. In the right part of the panel, precipitation was done with anti-PKCζ followed by detection with anti-STOML2. – indicates precipitation was performed with an irrelevant secondary Ab; and +, as described before. (E) In vitro phosphorylation of paratarg-7 with PKCζ. In an in vitro experiment purified recombinant wild-type paratarg-7 was incubated with recombinant PKCζ in the presence or absence of PKCζ pseudosubstrate. The figure shows an IEF followed by immunodetection of paratarg-7. 1 indicates recombinant E coli paratarg-7; 2, recombinant E coli paratarg-7 (0.5 μg) phosphorylated with recombinant PKCζ (0.5 μg) in the absence or 3, presence of PKCζ pseudosubstrate (50μM).

Identification of the kinase responsible for the hyperphosphorylation of paratarg-7. (A) Inhibition of kinases. LCLs derived from a healthy donor carrying wild-type paratarg-7 (row A) or a patient carrying hyperphosphorylated paratarg-7 (row B) were cultured in the presence of inhibitors (dissolved in DMSO) at the indicated concentrations. Lysates were analyzed by IEF and stained with anti-paratarg-7. Lane 1 indicates LCLs from healthy donor and patient, respectively, cultured with addition of DMSO (1:106) only. Hyperphosphorylation was inhibited by incubation with staurosporine (2.5μM, lane 2), ellagic acid (10μM, lane 10), and wortmannin (5nM, lane 11). No effect was observed by incubation with, lanes 3 to 9: H89 (50nM), Akt1,2 inhibitor (200nM), purvalanol (100nM), SL327 (200nM), SP600125 (100nM), SB202190 (50nM), and ZM447439 (1μM). As controls, lysates of healthy donor (lane 12), patient (lane 13), and recombinant paratarg-7 in Escherichia coli (lane 14) were also analyzed. Panel A is composed of 4 separate IEF gels. (B) Inhibition of paratarg-7 hyperphosphorylation by PKCζ pseudosubstrate in LCL derived from patients with pP-7. IEF followed by immunodetection of paratarg-7 in LCLs derived from healthy donor (lane 1) and from a patient (lane 2) as control. LCLs derived from a patient with pP-7 were cultured without inhibitors (lane 3) or in the presence of bisindolylmaleimide I (6μM, lane 4) or PKCζ pseudosubstrate (50μM, lane 5). (C) Demonstration of the direct interaction of Ser17 of paratarg-7 with PKCζ: only mutated fragments containing Ser17 interact with PKCζ. No interaction was detected when Ser was replaced by Ala. wt indicates unmutated paratarg-7 fragment spanning aa 1 to 60; Ser17Ala, fragment spanning aa 1 to 60 with Ser17 replaced by Ala; Ser21Ala, fragment spanning aa 1 to 60 with Ser21 replaced by Ala; Ser17Ala Ser21Ala, fragment spanning aa 1 to 60 with both serines replaced by Ala; –, control (carrier of wild-type paratarg-7 wtP-7); +, carrier of hyperphosphorylated paratarg-7 pP-7. (D) Coimmunoprecipitation of paratarg-7 and PKCζ in cell lines (HEK293, LP1) and LCLs derived from patients (P18, P39) and healthy donor (HD7). In the left portion of the panel, precipitation of the complex was done using anti-STOML2 (BD Biosciences) followed by detection of PKCζ in the redissolved precipitate using anti-PKCζ. In the right part of the panel, precipitation was done with anti-PKCζ followed by detection with anti-STOML2. – indicates precipitation was performed with an irrelevant secondary Ab; and +, as described before. (E) In vitro phosphorylation of paratarg-7 with PKCζ. In an in vitro experiment purified recombinant wild-type paratarg-7 was incubated with recombinant PKCζ in the presence or absence of PKCζ pseudosubstrate. The figure shows an IEF followed by immunodetection of paratarg-7. 1 indicates recombinant E coli paratarg-7; 2, recombinant E coli paratarg-7 (0.5 μg) phosphorylated with recombinant PKCζ (0.5 μg) in the absence or 3, presence of PKCζ pseudosubstrate (50μM).

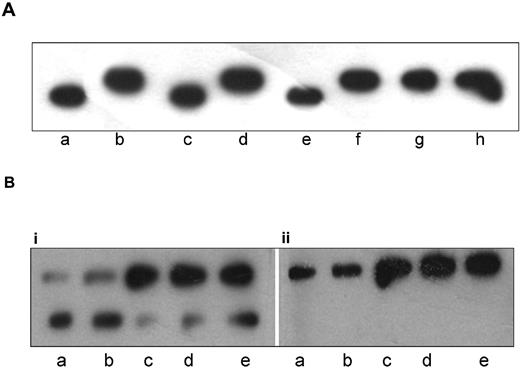

Demonstration of the trimeric complex of paratarg-7/PKCζ/PP2A by coimmunoprecipitation. Recombinant FLAG-tagged paratarg-7 expressed in HEK293 cells was precipitated using FLAG Abs (0.5 μg) and protein-G. The precipitate was subjected to PAGE followed by immunodetection with anti-FLAG (lanes a-b), anti-PP2A subunit C (lanes c-d) or anti-PKCζ (lanes e-f). As a negative control similarly expressed FLAG-tagged recombinant SMCHD1 protein was used. Lanes a, c, and e: control.

Demonstration of the trimeric complex of paratarg-7/PKCζ/PP2A by coimmunoprecipitation. Recombinant FLAG-tagged paratarg-7 expressed in HEK293 cells was precipitated using FLAG Abs (0.5 μg) and protein-G. The precipitate was subjected to PAGE followed by immunodetection with anti-FLAG (lanes a-b), anti-PP2A subunit C (lanes c-d) or anti-PKCζ (lanes e-f). As a negative control similarly expressed FLAG-tagged recombinant SMCHD1 protein was used. Lanes a, c, and e: control.

Hyperphosporylation of paratarg-7 by inactivation of PP2A

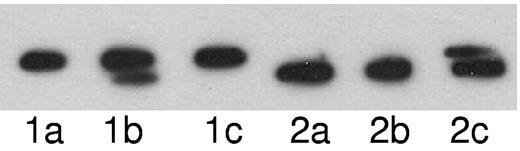

To test whether the observed hyperphosphorylation of paratarg-7 occurs because of a modified enzymatic activity in carriers of hyperphosphorylated paratarg-7, we transformed LCLs with a recombinant expression construct producing FLAG-tagged paratarg-7. After lysis and inactivation by heat, the “acceptor lysate” was incubated with a “donor lysate” that was obtained by lysis of the respective LCLs that had not been heat-inactivated. Using LCL extracts derived from a patient carrying pP-7 as acceptor and LCL extracts derived from a healthy donor carrying wild-type paratarg-7 as donor, phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of paratarg-7 was demonstrated (Figure 4). In a second experiment with reversed probes (acceptor lysate derived from LCLs of a healthy donor incubated with the extract derived from the LCLs of a pP-7 carrier), phosphorylation was demonstrated, but dephosphorylation (reversal to wild-type P-7) was not observed. This indicates that phosphorylation of paratarg-7 is operative, but dephosphorylation is inhibited in patients carrying pP-7.

Complementation assays. Acceptor lysate derived from the LCLs of a patient carrying hyperphosphorylated paratarg-7 (lanes 1a-1c) or from LCLs of a healthy carrier of wild-type paratarg-7 (lanes 2a-2c) were incubated with lysate buffer as control (lane a) or with donor lysates derived from the LCLs of a healthy carrier of wild-type paratarg-7 (lane b), or with lysates derived from the LCLs of a patient carrying hyperphosphorylated paratarg-7 (lane c). After incubation (37°C, 48 hours), the samples were subjected to IEF followed by immunodetection of FLAG-tagged paratarg-7 using FLAG Abs. In lane 1b, dephosphorylation of hyperphosphorylated paratarg-7 was observed, while in lane 1c no dephosphorylation was detected, indicating a compromised dephosphorylation in carriers of hyperphosphorylated paratarg-7. In the reverse approach using wild-type FLAG-tagged paratarg-7 as acceptor and LCL extracts (lanes 2a-2c) as donors, the upper band representing hyperphosphorylated paratarg-7 was only detected when extracts derived from LCLs of the patient carrying hyperphosphorylated paratarg-7 were used as donors (lane 2c).

Complementation assays. Acceptor lysate derived from the LCLs of a patient carrying hyperphosphorylated paratarg-7 (lanes 1a-1c) or from LCLs of a healthy carrier of wild-type paratarg-7 (lanes 2a-2c) were incubated with lysate buffer as control (lane a) or with donor lysates derived from the LCLs of a healthy carrier of wild-type paratarg-7 (lane b), or with lysates derived from the LCLs of a patient carrying hyperphosphorylated paratarg-7 (lane c). After incubation (37°C, 48 hours), the samples were subjected to IEF followed by immunodetection of FLAG-tagged paratarg-7 using FLAG Abs. In lane 1b, dephosphorylation of hyperphosphorylated paratarg-7 was observed, while in lane 1c no dephosphorylation was detected, indicating a compromised dephosphorylation in carriers of hyperphosphorylated paratarg-7. In the reverse approach using wild-type FLAG-tagged paratarg-7 as acceptor and LCL extracts (lanes 2a-2c) as donors, the upper band representing hyperphosphorylated paratarg-7 was only detected when extracts derived from LCLs of the patient carrying hyperphosphorylated paratarg-7 were used as donors (lane 2c).

Identification of the phosphatase responsible for the dephosphorylation of hyperphosphorylated paratarg-7

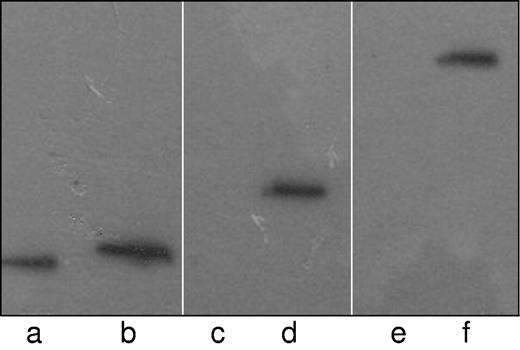

In T cells from healthy donors carrying wtP-7, temporary hyperphosphorylation of paratarg-7 can be induced by stimulation with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 Abs (Figure 5). Hyperphosphorylation becomes detectable on day 4 and persists until day 18. To identify the phosphatase involved in the reversal from the hyperphosphorylated to the wild-type state, protease inhibitor experiments with LCLs were performed. These identified protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) as responsible for the dephosphorylation of the hyperphosphorylated form of paratarg-7 (Figure 6A).

Induction of transient hyperphosphorylation of paratarg-7 in T-cells from healthy donors carrying wild-type paratarg-7. T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 for 48 hours. IEF analysis followed by immunodetection of paratarg-7 was done after the indicated days of incubation (d0-d21). Unstimulated T-cell lysates from a patient carrying hyperphosphorylated paratarg-7 (lane a) or from a healthy donor carrying wild-type paratarg-7 (lane b) were used as control. Hyperphosphorylated paratarg-7 becomes detectable on day 4 and persists until day 18.

Induction of transient hyperphosphorylation of paratarg-7 in T-cells from healthy donors carrying wild-type paratarg-7. T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 for 48 hours. IEF analysis followed by immunodetection of paratarg-7 was done after the indicated days of incubation (d0-d21). Unstimulated T-cell lysates from a patient carrying hyperphosphorylated paratarg-7 (lane a) or from a healthy donor carrying wild-type paratarg-7 (lane b) were used as control. Hyperphosphorylated paratarg-7 becomes detectable on day 4 and persists until day 18.

Identification of PP2A as the phosphatase responsible for the dephosphorylation of hyperphosphorylated paratarg-7. (A) Inhibition of phosphatases: LCLs derived from a healthy donor were cultured in the presence of inhibitors at indicated concentrations. Lysates were analyzed by IEF and stained with anti-paratarg-7. LCL lysates derived from a patient carrying hyperphosphorylated paratarg-7 (lane b) or from a healthy donor carrying wild-type paratarg-7 (lane a) and HEK293 cells (expressing wild-type paratarg-7, lane c) were used as controls. Incubation with serine/threonine phosphatase inhibitor cocktail 1 (Sigma-Aldrich; dilution 1:1000; lane d) and ocadaic acid (lane f, 500nM; lane g, 10nM; lane h, 0.1nM) inhibited the dephosphorylation resulting in the appearance of hyperphosphorylated paratarg-7. NIPP1 (10mM; lane e) had no effect. NIPP1 is a specific inhibitor of protein phosphatase 1 (PP1); ocadaic acid at 10nM inhibits both PP1 and PP2A, while at concentrations equal or below 0.1nM it inhibits only PP2A. (B) Analysis of PP2A subunit C derived from MM/MGUS patients and healthy donors: LCLs were subjected to IEF followed by immunodetection using PP2A subunit C Abs (1:1000; subpanel i) or pY307 specific Abs (1:1000; subpanel ii). The figure shows that in carriers of wild-type paratarg-7 (lanes a-b) the bottom band (representing the nonphosphorylated subunit) is dominant, while in patients carrying hyperphosphorylated paratarg-7 (lanes c-e) the upper band (representing the phosphorylated subunit) is dominant. Subpanel ii shows that the top band represents subunit C phosphorylated on Y307. Samples as in panel A.

Identification of PP2A as the phosphatase responsible for the dephosphorylation of hyperphosphorylated paratarg-7. (A) Inhibition of phosphatases: LCLs derived from a healthy donor were cultured in the presence of inhibitors at indicated concentrations. Lysates were analyzed by IEF and stained with anti-paratarg-7. LCL lysates derived from a patient carrying hyperphosphorylated paratarg-7 (lane b) or from a healthy donor carrying wild-type paratarg-7 (lane a) and HEK293 cells (expressing wild-type paratarg-7, lane c) were used as controls. Incubation with serine/threonine phosphatase inhibitor cocktail 1 (Sigma-Aldrich; dilution 1:1000; lane d) and ocadaic acid (lane f, 500nM; lane g, 10nM; lane h, 0.1nM) inhibited the dephosphorylation resulting in the appearance of hyperphosphorylated paratarg-7. NIPP1 (10mM; lane e) had no effect. NIPP1 is a specific inhibitor of protein phosphatase 1 (PP1); ocadaic acid at 10nM inhibits both PP1 and PP2A, while at concentrations equal or below 0.1nM it inhibits only PP2A. (B) Analysis of PP2A subunit C derived from MM/MGUS patients and healthy donors: LCLs were subjected to IEF followed by immunodetection using PP2A subunit C Abs (1:1000; subpanel i) or pY307 specific Abs (1:1000; subpanel ii). The figure shows that in carriers of wild-type paratarg-7 (lanes a-b) the bottom band (representing the nonphosphorylated subunit) is dominant, while in patients carrying hyperphosphorylated paratarg-7 (lanes c-e) the upper band (representing the phosphorylated subunit) is dominant. Subpanel ii shows that the top band represents subunit C phosphorylated on Y307. Samples as in panel A.

To define the PP2A amount and activation state of PP2A, we performed SDS-PAGE and IEF experiments using lysates of LCLs derived from healthy donors and patients carrying hyperphosphorylated paratarg-7 (Figure 6A). The catalytic subunit C of PP2A exists in 2 forms, 1 phosphorylated at Y307 and 1 not. In both patients and controls, the total amount of PP2A in LCLs was not different, but the ratio of phosphorylated to nonphosphorylated PP2A differed strikingly. In patients, the phosphorylated PP2A subunit C was abundant, while in healthy donors the nonphosphorylated form prevailed. Phosphorylation occurs on Y307 of subunit C (Figure 6B).

Demonstration of the trimeric complex of paratarg-7 with PKCζ and PP2A

To demonstrate the direct interaction of PKCζ and PP2A with paratarg-7, we performed coimmunoprecipitation experiments using LCLs. Using recombinant FLAG-tagged paratarg-7 as bait, we detected PKCζ and PP2A in the immunocomplex formed with paratarg-7 (Figure 3), indicating that both enzymes interact with paratarg-7 and both regulate the phosphorylation state of this protein. PKCζ was detected in 6 of 8 and PP2A in all 8 autoantigenic paraproteins targets tested (Table 1).

Kinases and phosphatases responsible for the hyperphosphorylation of autoantigenic targets of paraproteins

| Paratarg . | Ag . | Type of Ag . | Phosphorylation . | PKCζ . | PP2A . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cylicin 2 | Alloantigen | nd | nd | nd |

| 2 | TPP2 | Autoantigen | + | ∅ | + |

| 3 | IGFBP-2 | Autoantigen | nd | nd | nd |

| 4 | Porcine kinesin | Heteroantigen | nd | nd | nd |

| 5 | Microtubuli-associated protein | Autoantigen | + | + | + |

| 6 | LAPTM5 | Autoantigen | + | + | + |

| 7 | SLP-2 | Autoantigen | + | + | + |

| 8 | ATG13 | Autoantigen | + | + | + |

| 9 | RSP16 | Autoantigen | nd | + | + |

| 10 | SPAG7 | Autoantigen | + | ∅ | + |

| 11 | SIVA | Autoantigen | + | + | + |

| Paratarg . | Ag . | Type of Ag . | Phosphorylation . | PKCζ . | PP2A . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cylicin 2 | Alloantigen | nd | nd | nd |

| 2 | TPP2 | Autoantigen | + | ∅ | + |

| 3 | IGFBP-2 | Autoantigen | nd | nd | nd |

| 4 | Porcine kinesin | Heteroantigen | nd | nd | nd |

| 5 | Microtubuli-associated protein | Autoantigen | + | + | + |

| 6 | LAPTM5 | Autoantigen | + | + | + |

| 7 | SLP-2 | Autoantigen | + | + | + |

| 8 | ATG13 | Autoantigen | + | + | + |

| 9 | RSP16 | Autoantigen | nd | + | + |

| 10 | SPAG7 | Autoantigen | + | ∅ | + |

| 11 | SIVA | Autoantigen | + | + | + |

PKC indicates phosphokinase C; PP2A, phosphatase 2A; nd, no material available or patient did not sign informed consent for this experiment; and ∅, no specific coimmunoprecipitate with anti-PKCζ Ab.

Discussion

Our study yielded several significant results. First, we demonstrated that hyperphosphorylation of paratarg-7 occurs because of a single additional phosphorylation at Ser17. Second, the kinase PKCζ is involved in the hyperphosphorylation of most, and the phosphatase PP2A in the dephosphorylation of paratarg-7 and all other autoantigenic targets of paraproteins molecularly defined to date. Third, while no differences in PKCζ could be shown between carriers of the hyperphosphorylated and wild-type paratarg-7, the subunit C of PP2A was shown to be phosphorylated and hence inactive, thus being unable to reverse the hyperphosphorylated state of paratarg-7, which can be induced in carriers of wtP-7, to the wild-type state. Finally, our data suggest that inactivation of PP2A is a mechanism playing a general role in the pathogenesis of MGUS/MM/MW cases far beyond those for whom an autoantigenic target could be identified to date.

Peptidase treatment using trypsin and chymotrypsin on total blood lysates or LCLs followed by immunologic detection led to the identification of the phosphorylation site in the epitope region defined before as aa 16 to 25 of paratarg-7. By expression of site-directed mutagenized FLAG-tagged fragments of paratarg-7 in HEK293 cells a single additional phosphorylation at amino acid Ser17 was shown to be responsible for the hyperphosphorylation of paratarg-7 in patients with a paratarg-7–specific paraprotein compared with carriers of wild-type paratarg-7. With additional phosphorylation at other sites of the paratarg-7 molecule excluded, this finding demonstrates that the hyperphosphorylation of Ser17 is responsible for the immunogenicity of this paraprotein-binding epitope.

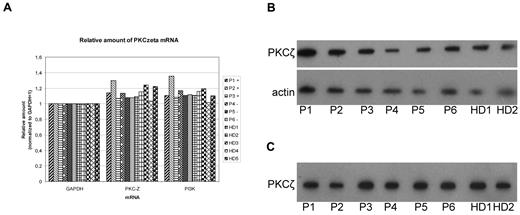

By complementation assays, we found that the phosphatase activity was reduced in carriers of pP-7 leading to the assumption that 2 enzymes are involved in the generation of the hyperphosphorylated state of paratarg-7 and that one of these enzymes appears to be modified in its reactivity compared with healthy donors. This conclusion led to the necessity to identify the kinase and the phosphatase responsible for the phosphorylation state of paratarg-7. We were able to identify PKCζ, an atypical kinase, as responsible for the phosphorylation of most, and PP2A, the most abundant phosphatase in mammalian cells, as responsible for the dephosphorylation of all hyperphosphorylated autoantigenic targets of paraproteins defined to date. Detailed analysis of PKCζ derived from patients and healthy controls showed no differences with respect to DNA sequence, copy number, or expression level in PBMCs and LCLs of patients and healthy donors. Similarly, no differences between carriers of wild-type and hyperphosphorylated paratarg-7 were found for the enzymes involved in the signaling pathway upstream of PKCζ, namely PI3K (Figure 7) and PTK1 (data not shown). Thus, in contrast to dephosphorylation, phosphorylation could be excluded as the mechanism responsible for the constitutive hyperphosphorylation of paratarg-7 in the respective carriers.

PKCζ expression in LCLs from different donors. The groups of donors were compared: MM/MGUS patients with (P1-P3) and without (P4-P6) paratarg-7 specificity of their paraprotein and healthy donors (HD1-HD5). (A) Quantitative RT-PCR for PKCζ, GAPDH, and PI3K was done as described. Values were normalized for GAPDH. (B) Immunodetection of PKCζ in 5 patients carrying hyperphosphorylated paratarg-7 (P1-5) and 2 healthy donors (HD1-2) carrying wild-type paratarg-7. (C) IEF analysis of these same samples.

PKCζ expression in LCLs from different donors. The groups of donors were compared: MM/MGUS patients with (P1-P3) and without (P4-P6) paratarg-7 specificity of their paraprotein and healthy donors (HD1-HD5). (A) Quantitative RT-PCR for PKCζ, GAPDH, and PI3K was done as described. Values were normalized for GAPDH. (B) Immunodetection of PKCζ in 5 patients carrying hyperphosphorylated paratarg-7 (P1-5) and 2 healthy donors (HD1-2) carrying wild-type paratarg-7. (C) IEF analysis of these same samples.

The enzyme involved in the dephosphorylation of hyperphosphorylated paratarg-7 was shown to be PP2A. PP2A belongs to the serine/threonine-specific family of phosphatases and is the most abundant phosphatase in mammalian cells14 regulating many fundamental cellular processes. In its form as an activated phosphatase, PP2A is a tumor suppressor; however, when PP2A is phosphorylated at the tyrosine residue Y307, it looses its phosphatase activity and becomes inactivated.15,16 The predominant form of PP2A is a heterotrimeric holoenzyme consisting of a scaffolding/structural subunit (A), a regulatory subunit (B), and a catalytic subunit (C). The regulatory B subunit is the substrate-targeting subunit of PP2A represented by 4 distinct families B, B′, B′′, and B′′′. Multiple isoforms exist within each family and they share significant amino acid homologies as well as some of the same substrates, whereas regulatory B subunits of different families lack amino acid homology and have distinct functions.17 The diversity of its subunits provides a large spectrum of PP2A isoforms and enables PP2A to be selective and to affect a wide range of different functions within the cell.

Although no difference in the total amount of PP2A message and protein in LCLs was found between patients with wild-type and hyperphosphorylated PP2A, the phosphorylation state of PP2A subunit C was found to be modified. In contrast to healthy donors, all patients with a paraprotein targeting the described autoantigens showed a more intense phosphorylation at Y307 of subunit C. Because posttranslational modifications such as phosphorylation18-20 or methylation20 of the PP2A subunits regulate PP2A complex formation and activity, our finding of a prevalence of PP2A with a phosphorylation of its catalytic subunit C at amino acid Y307 explains the failure of PP2A to reverse the hyperphosphorylated state of paratarg-7 in the respective patients.15,16 A logical next step is now the identification of the gene responsible for the phosphorylation of the catalytic subunit of PP2A at Y307.

Two major questions remain to be answered. First, why is only the autoantigen hyperphosphorylated in a patient that is targeted by her/his paraproteins, while the other autoantigens that are targeted by the paraproteins of other patients are not hyperphosphorylated in the respective patient although they are expressed in her/his cells? The second question addresses the (modified) gene and its product that is responsible for the phosphorylation of the catalytic subunit C of PP2A and thus is responsible for the hyperphosphorylation of the autoantigenic targets of paraproteins from patients with MGUS/MM/WM. With the availability of DNA derived from numerous carriers of wild-type and hyperphosphorylated autoantigenic targets of paraproteins, the latter question should be answerable using linkage and genome-wide association studies.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all patients for participating in the study.

This work was supported by Förderverein Krebsforschung Saar-Pfalz-Mosel, HOMFOR (the research program of the Saarland University Faculty of Medicine), Wilhelm Sander-Stiftung, Deutsche Krebshilfe, and Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

Authorship

Contribution: K.-D.P. designed experiments and wrote the manuscript; M.K., K.-H.S., and F.N. designed experiments; N.F., E.R., and S.R. performed and analyzed the experiments; N.M., M.A., and J.B. recruited and provided clinical information of the patients included in this study; G.H. established the wild-type P-7 and pP-7–specific Fab constructs used for the ELISA; and M.P. and S.G. designed the study and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: K.-D.P. and M.P. have applied for a relevant patent. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Michael Pfreundschuh, MD, Department Internal Medicine I, Saarland University Medical School, Kirrberger St, D-66421 Homburg, Germany; e-mail: michael.pfreundschuh@uks.eu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal