Abstract

Transcranial Doppler (TCD) is used to detect children with sickle cell anemia (SCA) who are at risk for stroke, and transfusion programs significantly reduce stroke risk in patients with abnormal TCD. We describe the predictive factors and outcomes of cerebral vasculopathy in the Créteil newborn SCA cohort (n = 217 SS/Sβ0), who were early and yearly screened with TCD since 1992. Magnetic resonance imaging/magnetic resonance angiography was performed every 2 years after age 5 (or earlier in case of abnormal TCD). A transfusion program was recommended to patients with abnormal TCD and/or stenoses, hydroxyurea to symptomatic patients in absence of macrovasculopathy, and stem cell transplantation to those with human leukocyte antigen-genoidentical donor. Mean follow-up was 7.7 years (1609 patient-years). The cumulative risks by age 18 years were 1.9% (95% confidence interval [95% CI] 0.6%-5.9%) for overt stroke, 29.6% (95% CI 22.8%-38%) for abnormal TCD, which reached a plateau at age 9, whereas they were 22.6% (95% CI 15.0%-33.2%) for stenosis and 37.1% (95% CI 26.3%-50.7%) for silent stroke by age 14. Cumulating all events (stroke, abnormal TCD, stenoses, silent strokes), the cerebral risk by age 14 was 49.9% (95% CI 40.5%-59.3%); the independent predictive factors for cerebral risk were baseline reticulocytes count (hazard ratio 1.003/L × 109/L increase, 95% CI 1.000-1.006; P = .04) and lactate dehydrogenase level (hazard ratio 2.78/1 IU/mL increase, 95% CI1.33-5.81; P = .007). Thus, early TCD screening and intensification therapy allowed the reduction of stroke-risk by age 18 from the previously reported 11% to 1.9%. In contrast, the 50% cumulative cerebral risk suggests the need for more preventive intervention.

MedscapeCME Continuing Medical Education online

This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the Essential Areas and policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education through the joint sponsorship of Medscape, LLC and the American Society of Hematology. Medscape, LLC is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

Medscape, LLC designates this Journal-based CME for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with their participation in the activity.

All other clinicians completing this activity will be issued a certificate of participation. To participate in this journal CME activity: (1) review the learning objectives and author disclosures; (2) study the education content; (3) take the post-test and/or complete the evaluation at http://cme.medscape.com/journal/blood; and (4) view/print certificate. For CME questions, see page 1436.

Disclosures

The authors, the Associate Editor Narla Mohandas, and the CME questions author Charles P. Vega, University of California, Irvine, CA, declare no competing financial interests.

Learning objectives

Upon completion of this activity, participants will be able to:

Identify the most common cerebrovascular outcomes among children with SCA

Evaluate the epidemiology of cerebrovascular abnormalities among children with SCA

Analyze variables associated with a higher risk for cerebrovascular outcomes among children with SCA

Assess treatment outcomes for children with SCA

Release date: January 27, 2011; Expiration date: January 27, 2012

Introduction

Sickle cell anemia (SCA) is an inherited, severe disease, resulting in early death and morbidity. Newborn screening,1-4 early preventive penicillin therapy,5 and pneumococcal vaccines have significantly reduced the incidence of early mortality.6-8 Nevertheless, morbidity remains high for SCA (SS/Sβ0) patients, with a reported absolute risk of 11%9 by age 20 years for overt stroke and a cumulative stroke risk of11.5% by age 18 years10 and 12.8% by age 20 years11 in the most recently studied newborn-cohorts.

In 1992, transcranial Doppler (TCD) screening was demonstrated to efficiently detect SCD patients at risk of stroke.12 In 1998, prophylactic red-cell-chronic-transfusion programs were shown to significantly reduce the incidence of strokes among patients identified at risk (Stroke Prevention Trial in Sickle Cell Anemia [STOP-I]).13 In 2004, a decreasing stroke rate was reported14 ; however, no study has examined cerebral vasculopathy outcomes in a newborn cohort assessed early by TCD in the era of intensive therapies, that is, chronic transfusion programs, hydroxyurea, and/or stem cell transplantation.

Methods

The Créteil Pediatric Sickle Cell Referral Center resides at the Créteil-Intercommunal-Hospital, known as CHIC, on the University Paris-Val-de-Marne campus. Newborn screening via the use of isoelectrofocusing and SCA diagnosis confirmed by high-pressure liquid chromatography began in 1986 in several maternity units and was extended to the Val-de-Marne department in 1995 before its full extension in France in 2000.1,2

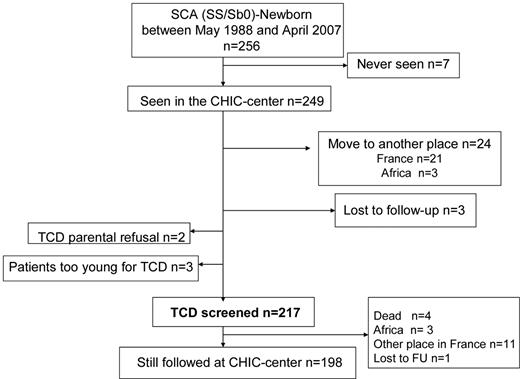

For the purpose of this study, the population referred to here as SCA includes all patients with homozygous sickle cell anemia (SS), sickle-cell/β0-thalassemia (Sβ0), sickle-cell/D-Punjab, and sickle cell/O-Arab. Patients with SC and sickle-cell/β+-thalassemia were excluded from this study. Patients were clinically evaluated every 3 months, and a complete check-up was performed every year. The present study reports the outcomes of consecutive SCA patients born between May 1988 and April 2007 who were followed regularly at the CHIC-SCD-center until age 18-20 years and screened early with TCD (Figure 1).

After introduction of TCD at the CHIC-SCD-Center (May 1992),15 patients were systematically assessed by TCD once a year at steady state from the age of 12-18 months,16,17 with the use of a duplex color Doppler instrument (Acuson; Siemens and, after 2003, Logic 9; GE Healthcare). The highest time-averaged mean velocities (TAMMX; cm/s), recorded in middle cerebral (MCA), internal carotid (ICA), and anterior cerebral (ACA) arteries after the entire course of the vessel was tracked every 2 mm in depth without angle correction were all used to classify TCD13 as either normal (< 170 cm/s), conditional (170-199 cm/s), abnormal (≥ 200 cm/s), or inadequate (unavailable temporal windows). Any patient with conditional TCD was then evaluated every 3 months. Starting in May 1993, magnetic resonance imaging/magnetic resonance angiography (MRI/MRA) without sedation was performed every 2 years in children older than 5 years of age and earlier in patients on chronic transfusion for abnormal TCD, and systematically before SCT. MRI/MRA used a GE Signa HD 1.5-T(GE Healthcare) with FLAIR, T1-, T2 diffusion-weighted sequences and 3-dimensional time-of-flight angiography, and all MRI/MRA imaging was reviewed by the same expert (SV).

Between 1993 and 1997, chronic transfusion was recommended to patients with evidence of stenosis by arteriography or MRA15 ; however, following Adams et al's12 recommendations in 1998, we placed all patients with 2 abnormal TCD,13 including in the absence of stenosis, on chronic transfusion. In August 2001, one patient had a stroke just before the confirmatory TCD18 ; for that reason and to avoid exposing patients with high velocities to the risk of stroke, the CHIC-SCD-Center decided at that time to transfuse patients after the first abnormal TCD. The hemoglobin level was always checked the same day as the TCD assessment. If an unusually low hemoglobin level was detected, as observed with splenic sequestrations or erythroblastopenia, the patient was then treated with a single transfusion, and the TCD was repeated 3 months later.

Since 1992, hydroxyurea has been used in patients older than 3 years of age who experience frequent vaso-occlusive crisis (VOC) and/or acute chest syndromes (ACS).19,20 Because of the proven negative effect of anemia on cognitive performance21 and the observation that patients on hydroxyurea had no decrease in their cognitive performance whereas the nontreated patients did,22 the decision was made in 2000 to also give hydroxyurea to patients with normal TCD and hemoglobin < 7 g/dL. Moreover, in a subset of patients with abnormal TCD history but normal velocities on transfusion program and normal MRA,18 hydroxyurea was recommended to avoid long-term transfusion programs. This decision was justified by the fact that up to 60% of patients with abnormal velocities do not develop a stroke,12,13 that velocities correlate with the degree of anemia,12,15 and that hydroxyurea significantly increases the hemoglobin levels22-24 and decreases velocities.23 Nevertheless, because we and others25 noted that hydroxyurea may not reverse vascular changes, only patients with normal MRA18 and velocities normalization on chronic transfusion (< 170 cm/s) received hydroxyurea. In addition, a 2-month transfusion overlap was set up at the start of therapy, the TCD was controlled every 3 months,8 and transfusions were immediately reinstated18 in case of abnormal TCD recurrence or new evidence of stenosis. Stem cell transplantation was recommended to patients with cerebral vasculopathy or frequent VOC/ACS who had an available human leukocyte antigen–identical sibling.26,27

Collection of data

Parental written informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and data were prospectively and systematically collected in a clinical database. Use of the database was approved for this project by the Créteil Institutional Review Board. Follow-up was from May 1988 to August 2008. Alpha-genes, beta-globin haplotypes, G6PD-enzymatic-activity, and baseline biologic parameters (Table 1) were determined.

SCA patients: clinical and biological characteristics

| Values . | No. . | Percent . |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| F | 102 | 47 |

| M | 115 | 53 |

| G6PD | ||

| Deficiency | 21 | 11.5 |

| Normal | 161 | 88.5 |

| Alpha genes | ||

| 2 | 15 | 8 |

| 3 | 67 | 35.8 |

| 4 | 104 | 55.6 |

| 5 | 1 | 0.5 |

| α-Thalassemia | ||

| Absent | 105 | 56.1 |

| Present | 82 | 43.9 |

| Beta haplotype | ||

| Car/Car | 67 | 43.8 |

| Ben/Ben | 36 | 23.5 |

| Sen/Sen | 11 | 7.2 |

| Others | 39 | 25.5 |

| Parameters at baseline, median (Q1-Q3) | ||

| WBC count, ×109/L | 183 | 14.200 (10.750-17.850) |

| Neutrophil count, ×109/L | 171 | 5.320 (3.855-7.955) |

| Platelet count, ×109/L | 182 | 355.000 (282.500-434.000) |

| Hemoglobin level, g/dL | 185 | 7.8 (7.2-8.7) |

| Hematocrit, % | 179 | 23.4 (21.6-27) |

| MCV, flt | 178 | 80.35 (74.23-85.2) |

| Reticulocyte count, ×109/L | 173 | 286.200 (213.400-359.200) |

| HbF, % | 169 | 13.3 (8.1-20.7) |

| SpO2, % | 69 | 98 (97-100) |

| LDH, IU/L | 163 | 978 (760.5-1210) |

| Values . | No. . | Percent . |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| F | 102 | 47 |

| M | 115 | 53 |

| G6PD | ||

| Deficiency | 21 | 11.5 |

| Normal | 161 | 88.5 |

| Alpha genes | ||

| 2 | 15 | 8 |

| 3 | 67 | 35.8 |

| 4 | 104 | 55.6 |

| 5 | 1 | 0.5 |

| α-Thalassemia | ||

| Absent | 105 | 56.1 |

| Present | 82 | 43.9 |

| Beta haplotype | ||

| Car/Car | 67 | 43.8 |

| Ben/Ben | 36 | 23.5 |

| Sen/Sen | 11 | 7.2 |

| Others | 39 | 25.5 |

| Parameters at baseline, median (Q1-Q3) | ||

| WBC count, ×109/L | 183 | 14.200 (10.750-17.850) |

| Neutrophil count, ×109/L | 171 | 5.320 (3.855-7.955) |

| Platelet count, ×109/L | 182 | 355.000 (282.500-434.000) |

| Hemoglobin level, g/dL | 185 | 7.8 (7.2-8.7) |

| Hematocrit, % | 179 | 23.4 (21.6-27) |

| MCV, flt | 178 | 80.35 (74.23-85.2) |

| Reticulocyte count, ×109/L | 173 | 286.200 (213.400-359.200) |

| HbF, % | 169 | 13.3 (8.1-20.7) |

| SpO2, % | 69 | 98 (97-100) |

| LDH, IU/L | 163 | 978 (760.5-1210) |

Average biologic parameters were obtained at baseline after the age of 12 months and before the age of 3 years, a minimum of 3 months away from a transfusion, 1 month from a painful episode, and before any intensive therapy (hydroxyurea, transfusion program, or stem cell transplantation). G6PD activity was assessed by reduction of NADP to NADPH, measured by ultraviolet spectrophotometry. LDH range for the institution: 135-225 IU/L.

HbF indicates fetal hemoglobin; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; and SCA, sickle cell anemia.

Intensive therapy was defined as chronic transfusion program (≥ 4 months), hydroxyurea, or stem cell transplantation. A stroke was defined as an acute neurologic deficit with new ischemic lesions on MRI or a neurologic deficit lasting more than 24 hours in the absence of new ischemic lesions on MRI. Stenosis was defined as at least 50% decrease in the lumen of MCA, ICA, or ACA. A silent stroke was defined as an MRI signal abnormality measuring at least 3 mm in one dimension, visible on 2 views on the T2-weighted images, and observed in a patient with no history of overt stroke and normal neurologic examination.

Statistical analysis

Participant baseline characteristics were summarized through the use of percentages, and mean (SD) or median with 25th and 75th percentiles denoted Q1-Q3. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals (95% CI) around point estimates were computed. Fisher exact tests were used to compare proportions and Wilcoxon rank sum tests to compare continuous distributions.

Birth date defined entry into study. Participants were censored on the date of death or last visit for KM estimates of survival and on the date of stroke or last visit for KM estimates of stroke. Data were censored at the date of event, that is, abnormal TCD or MRA, silent stroke, or last TCD or MRI/MRA for risks assessed by TCD, MRI/MRA. Failure time data curves were compared across baseline groups by the log-rank test. Because only 4 deaths occurred, they were not considered as competing risks for studied events but treated as noninformative censoring observations at the time of death, similar to children who had not experienced any event of interest and were censored at the time of their last visit. The median interval time of conversion from conditional to abnormal TCD was determined.

The association between outcomes and baseline variables was assessed using Cox regression with estimated hazards ratio (HR) and 95% CI. Because of the number of patients at risk, only events (stenosis, silent strokes) that occurred before the age of 14 years were analyzed. Univariable models were fitted, and all variables associated with the outcome at the 10% level were retained for introduction into a multivariable model. Multivariate analyses used an SAS stepwise selection process that consists of a series of alternating forward selection and backward elimination steps. The former adds variables to the model whereas the latter removes variables from the model. All statistical tests were 2-sided, with P values of .05 or less denoting statistical significance. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS, version 16, SAS 9.2 (SAS Inc), MedCalc (http://www.medcalc.org/), and R (http://www.R-project.org) software packages.

Results

Of 256 SCA newborns screened at birth in the Créteil area between May 1988 and April 2007, 7 were never seen at the CHIC SCD Center, 24 moved before 1 year of age, 3 were lost to follow-up, 2 had parents refusing TCD assessment, and 3 were still too young for TCD at censure; therefore, 217 children, all consecutively seen at CHIC SCD Center before 2 months of age and early assessed with TCD were included in the CHIC SCA newborn cohort (Figure 1). The main characteristics of the participants, grouped as SCA (n = 217: 209 SS, 6 Sβ0, 2 SD-Punjab), are summarized in Table 1. A total of 1351 TCD were performed at annual check-ups, with a median number of TCD/patient of 6 (range, 1-16). MRI/MRA (n = 463) were performed in 132 SCA patients. The median number of MRI/MRA per patient was 2 (range, 1-8). In patients older than 5 years, MRI/MRA without sedation failed in 2 patients.

Survival

Mean (SD) follow-up was 7.7 (5.0) years, and median follow-up was 6.2 years (range, 0.8-19.2 years), providing 1609 patient-years. Four SCA patients died before the age of 5 years. The first child, who had not received the PNEUMOVAX-23 vaccine (Sanofi Pasteur MSD SNC), had fatal pneumococcal meningitis and died in 1997 at the age of 1.9 years. The second child died in 1999 at the age of 4.8 years while he was being treated for ACS in an intensive care unit and developed a fatal curare allergy after intubation. The third child died at the age of 1.8 years during a trip to Africa, and the fourth had a fatal massive thrombotic stroke at 4.2 years of age when he was hospitalized in an intensive care unit for ACS. The incidence of death was 0.25/100 patient-years (95% CI 0.07-0.63), resulting in a survival probability at 18 years of 97.5% (95% CI 93.4%-99.1%).

Strokes

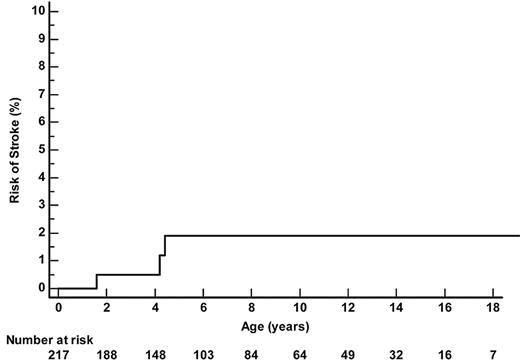

Three SCA-patients had a stroke (Figure 2). One patient had an abnormal TCD at 1.5 years of age (235 cm/s on left MCA) and had a stroke 1 month later, just before the confirmatory TCD. Another child had normal left-sided velocities but no available temporal window on the right side and had a stroke related to severe right MCA stenosis at 4.4 years of age. The third child had normal TCD but developed a febrile ACS at age 4.2 years, requiring a transfer to intensive care; despite a favorable pulmonary resolution after a simple 10 mL/kg transfusion, he experienced a massive bilateral MCA and ACA thrombosis and died. Thus, the overall incidence of strokes in SCA patients was 0.19/100 patient-years (95% CI 0.04-0.5) and the cumulative risk of strokes by age 18 years was 1.9% (95% CI 0.6%-5.9%).

Velocities on TCD

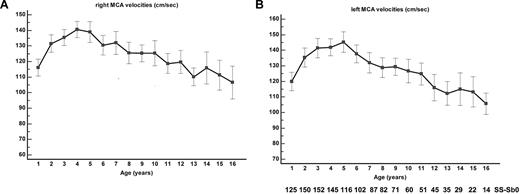

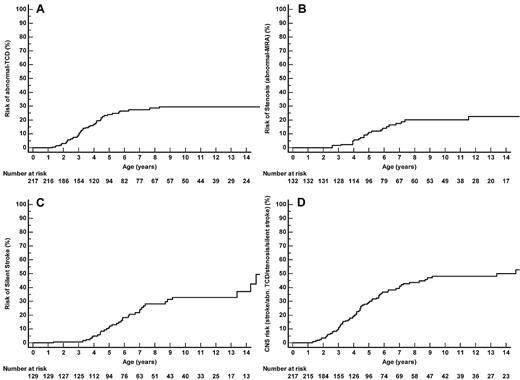

The MCA TAMMX velocities (mean ± SD) over time are shown in Figure 3A-B. Conditional TCD (170-199 cm/s) occurred in 58 of 217 patients and became abnormal in 20 of 58 patients (34.5% conversion rate). TCD was abnormal (≥ 200 cm/s) in 45 of 217 SCA-patients at the median age of 3.2 years (range, 1.3-8.3 years). Abnormal TCD was first observed in 11 patients; in 20 of 45 cases, conditional TCD was observed before occurrence of abnormal TCD at the median age of 2.5 years (range, 1.2-5.5 years). The median interval time for conversion from conditional to abnormal was 1.1 years (range, 0.03-7 years). Being younger than 4 years of age was a significant risk factor for conversion (odds ratio 6.7; 95% CI 1.7-27; P = .007). The cumulative risk of abnormal TCD by age 14 years was 29.6% (95% CI 22.8%-38.0%), with a “plateau” starting at age 9 years (Figure 4A).

MCA velocities. (A) Right and (B) left TAMMX ( ± SD) MCA velocities at annual check-up.

MCA velocities. (A) Right and (B) left TAMMX ( ± SD) MCA velocities at annual check-up.

Stenosis (abnormal MRA)

Twenty-two patients developed stenosis at the median age of 4.8 years (range, 2.6-11.5 years). Stenoses were unilateral in 13 patients and bilateral in 9 patients and involved right MCA (n = 7), left MCA (n = 13), right ACA (n = 12), left ACA (n = 11), right ICA (n = 1), and left ICA (n = 3). The cumulative risk of stenosis by age 14 was 22.6% (95% CI 15.0%-33.2%; Figure 4B).

Silent strokes

Silent strokes were detected in 35 of 132 SCA-patients (3.4/100 patient-years, 95% CI 2.4-4.8). The cumulative risk of silent stroke was 28.2% (95% CI 20.2%-38.5%) by age 8 and 37.4% (95% CI 26.3%-50.7%) by age 14 (Figure 4C). Of note, patients who developed a first silent stroke after age 8 were all males.

Cumulative risk. (A) Cumulative risk of abnormal TCD (TAMMX velocities ≥ 200 cm/s). (B) Cumulative risk of abnormal MRA (stenosis). Of the 22 SS/Sβ0-patients with abnormal MRA, 16 had a history of abnormal TCD, 2 had conditional TCD, and 4 had normal TCD (1 had an extracranial cerebral vasculopathy, 1 had inadequate window on one side and normal velocities on the other side, and for the last 2, anomalies might have been related to flow artifact because the repeat MRA was normal). (C) Cumulative risk of silent strokes. Among the 35 SS/Sβ0 patients with silent strokes, 28 had silent strokes on the first MRI, and secondary occurrence of silent strokes was only observed in 7 boys: 1 had a history of abnormal TCD but parents had refused long-term TP, 1 with abnormal TCD still had abnormal velocities despite TP, and 5 nonintensified patients developed silent strokes. (D) Cumulative cerebral vasculopathy risk (strokes, abnormal TCD, stenosis, or silent strokes).

Cumulative risk. (A) Cumulative risk of abnormal TCD (TAMMX velocities ≥ 200 cm/s). (B) Cumulative risk of abnormal MRA (stenosis). Of the 22 SS/Sβ0-patients with abnormal MRA, 16 had a history of abnormal TCD, 2 had conditional TCD, and 4 had normal TCD (1 had an extracranial cerebral vasculopathy, 1 had inadequate window on one side and normal velocities on the other side, and for the last 2, anomalies might have been related to flow artifact because the repeat MRA was normal). (C) Cumulative risk of silent strokes. Among the 35 SS/Sβ0 patients with silent strokes, 28 had silent strokes on the first MRI, and secondary occurrence of silent strokes was only observed in 7 boys: 1 had a history of abnormal TCD but parents had refused long-term TP, 1 with abnormal TCD still had abnormal velocities despite TP, and 5 nonintensified patients developed silent strokes. (D) Cumulative cerebral vasculopathy risk (strokes, abnormal TCD, stenosis, or silent strokes).

Cerebral vasculopathy

Table 2 reports the number of patients in each category of cerebral vasculopathy. When considering all events (strokes, abnormal TCD, stenosis, or silent strokes), the cumulative cerebral vasculopathy risk by age 14 was 49.9% (95% CI 40.5%-59.3%; Figure 4D).

Patients assessed with TCD and MRI/MRA (n = 132): distribution of patients in each category of cerebral vasculopathy

| . | n . |

|---|---|

| TCD and MRI/MRA performed | 132 |

| Normal TCD and MRA, no stroke, no silent stroke (no cerebral vasculopathy risk) | 66 |

| Isolated abnormal TCD | 17 |

| Isolated abnormal MRA | 2 |

| Isolated silent stroke | 21 |

| Abnormal TCD + abnormal MRA | 9 |

| Abnormal TCD + silent stroke | 5 |

| Abnormal MRA + silent stroke | 3 |

| Abnormal TCD + abnormal MRA + silent stroke | 6 |

| Abnormal TCD + abnormal MRA + overt stroke | 1 |

| Normal TCD + overt stroke | 1 |

| Unavailable TCD + abnormal MRA + overt stroke | 1 |

| Stroke or abnormal TCD or abnormal MRA or silent stroke (cerebral vasculopathy risk) | 66 |

| . | n . |

|---|---|

| TCD and MRI/MRA performed | 132 |

| Normal TCD and MRA, no stroke, no silent stroke (no cerebral vasculopathy risk) | 66 |

| Isolated abnormal TCD | 17 |

| Isolated abnormal MRA | 2 |

| Isolated silent stroke | 21 |

| Abnormal TCD + abnormal MRA | 9 |

| Abnormal TCD + silent stroke | 5 |

| Abnormal MRA + silent stroke | 3 |

| Abnormal TCD + abnormal MRA + silent stroke | 6 |

| Abnormal TCD + abnormal MRA + overt stroke | 1 |

| Normal TCD + overt stroke | 1 |

| Unavailable TCD + abnormal MRA + overt stroke | 1 |

| Stroke or abnormal TCD or abnormal MRA or silent stroke (cerebral vasculopathy risk) | 66 |

MRI/MRA indicates magnetic resonance imaging/magnetic resonance angiography; and TCD, transcranial Doppler.

Predictive analysis of outcomes

Table 3 reports the results of the Cox-regression univariate and multivariate analyses performed to assess baseline predictive factors associated with abnormal TCD, abnormal MRA (stenosis), and silent stroke.

Baseline prognostic factors for abnormal TCD, abnormal MRA, silent strokes, and cerebral vasculopathy risk (strokes, abnormal TCD, abnormal MRA, or silent strokes) by the age of 14 years in SCA participants

| Baseline parameters . | Abnormal TCD . | Abnormal MRA . | Silent strokes . | Stroke or abnormal TCD or abnormal MRA or silent stroke . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | No. events/ . | HR (95% CI) . | P . | No. events/ . | HR (95% CI) . | P . | No. events/ . | HR (95% CI) . | P . | No. events/ . | HR (95% CI) . | P . |

| No. patients . | No. patients . | No. patients . | No. patients . | . | . | |||||||

| Univariate analysis | ||||||||||||

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male | 25/115 = 22% | 1.1 (0.6-1.9) | .86 | 10/71 = 14% | 0.7 (0.3-1.6) | .4 | 21/67 = 31% | 1.6 (0.8-3.4) | .065 | 40/71 = 56% | 1.3 (0.8-2.2) | .253 |

| Female | 20/102 = 20% | 1 | 12/61 = 20% | 11/59 = 19% | 26/61 = 43% | |||||||

| G6PD | ||||||||||||

| Normal | 31/161 = 19% | 1 | 11/100 = 11% | 24/97 = 25% | 49/100 = 49% | |||||||

| Deficiency | 10/21 = 48% | 2.0 (1.0-4.0)* | .042* | 8/16 = 50% | 4.8 (1.9-11.9)* | .001* | 7/13 = 54% | 2.0 (0.9-4.3) | .072 | 13/16 = 81% | 1.8 (0.9-3.3) | .082 |

| α-Thalassemia | ||||||||||||

| Present | 09/82 = 11% | 1 | 2/51 = 3.9% | 13/50 = 26% | 20/51 = 39% | |||||||

| Absent | 30/105 = 29% | 2.8 (1.3-5.8)* | .007* | 16/74 = 22% | 3.7 (1.1-12.7)* | .038* | 18/69 = 26% | 1.1 (0.5-2.1) | .936 | 43/74 = 58% | 1.6 (0.9-2.6) | .116 |

| Leukocyte count per 1 × 109/L increase | 1.1 (1.0-1.1)* | .001* | 1.1 (1.0-1.2)* | .003* | 1.0 (0.9-1.1) | .707 | 1.0 (0.9-1.1) | .061 | ||||

| Neutrophil count per 1 × 109/L increase | 1.0 (0.9-1.1) | .546 | 1.0 (0.9-1.2) | .725 | 0.9 (0.8-1.1) | .336 | 1.0 (0.9-1.1) | .64 | ||||

| Platelet count per 1 × 109/L increase | 1.0 (1.0-1.0) | .235 | 0.9 (0.6-1.4) | .643 | 1.0 (1.0-1.0) | .477 | 1.0 (1.0-1.0) | .38 | ||||

| Hemoglobin level per 1 g/dL increase | 0.73(0.54-0.97)* | .034* | 0.47 (0.28-0.79)* | .004* | 0.67 (0.46-0.98)* | .048* | 0.77 (0.60-1.00)* | .050* | ||||

| MCV per (fL) increase | 1.04 (0.99-1.08) | .053 | 1.05 (0.98-1.12) | .149 | 1.02 (0.98-1.07) | .292 | 1.03 (0.99-1.07) | .069 | ||||

| Reticulocyte count per 1 × 109/L increase | 1.005 (1.002-1.008) | .001* | 1.005 (1.000-1.010) | .069 | 1.0 (1.0-1.0) | .641 | 1.003 (1.000-1.005)* | .028* | ||||

| HbF per 1% increase | 1.02 (0.98-1.06) | .279 | 0.98 (0.91-1.06) | .688 | 0.97 (0.92-1.03) | .265 | 1.0 (1.0-1.0) | .94 | ||||

| LDH per IU/mL increase | 2.73 (1.14-5.64)* | .024* | 7.31 (1.91-27.92)* | .004* | 2.06 (0.72-5.88) | .177 | 3.31 (1.61-6.83)* | .001* | ||||

| Multivariate analysis | ||||||||||||

| G6PD deficiency | 2.3 (1.0-5.2)* | .046* | 3.6 (1.2-11.0)* | .024* | ||||||||

| Absence of α-thalassemia | 2.5 (1.04-5.0)* | .041* | ||||||||||

| Hemoglobin level per 1 g/dL decrease | 1.7 (1.1-2.8)* | .011* | ||||||||||

| Reticulocyte count per 1 × 109/L increase | 1.005* (1.002-1.008)* | <.001* | 1.003 (1.000-1.006)* | .04* | ||||||||

| LDH per IU/mL increase | 4.9 (1.2-19.7)* | .027* | 2.78 (1.33-5.81)* | .007* | ||||||||

| Baseline parameters . | Abnormal TCD . | Abnormal MRA . | Silent strokes . | Stroke or abnormal TCD or abnormal MRA or silent stroke . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | No. events/ . | HR (95% CI) . | P . | No. events/ . | HR (95% CI) . | P . | No. events/ . | HR (95% CI) . | P . | No. events/ . | HR (95% CI) . | P . |

| No. patients . | No. patients . | No. patients . | No. patients . | . | . | |||||||

| Univariate analysis | ||||||||||||

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male | 25/115 = 22% | 1.1 (0.6-1.9) | .86 | 10/71 = 14% | 0.7 (0.3-1.6) | .4 | 21/67 = 31% | 1.6 (0.8-3.4) | .065 | 40/71 = 56% | 1.3 (0.8-2.2) | .253 |

| Female | 20/102 = 20% | 1 | 12/61 = 20% | 11/59 = 19% | 26/61 = 43% | |||||||

| G6PD | ||||||||||||

| Normal | 31/161 = 19% | 1 | 11/100 = 11% | 24/97 = 25% | 49/100 = 49% | |||||||

| Deficiency | 10/21 = 48% | 2.0 (1.0-4.0)* | .042* | 8/16 = 50% | 4.8 (1.9-11.9)* | .001* | 7/13 = 54% | 2.0 (0.9-4.3) | .072 | 13/16 = 81% | 1.8 (0.9-3.3) | .082 |

| α-Thalassemia | ||||||||||||

| Present | 09/82 = 11% | 1 | 2/51 = 3.9% | 13/50 = 26% | 20/51 = 39% | |||||||

| Absent | 30/105 = 29% | 2.8 (1.3-5.8)* | .007* | 16/74 = 22% | 3.7 (1.1-12.7)* | .038* | 18/69 = 26% | 1.1 (0.5-2.1) | .936 | 43/74 = 58% | 1.6 (0.9-2.6) | .116 |

| Leukocyte count per 1 × 109/L increase | 1.1 (1.0-1.1)* | .001* | 1.1 (1.0-1.2)* | .003* | 1.0 (0.9-1.1) | .707 | 1.0 (0.9-1.1) | .061 | ||||

| Neutrophil count per 1 × 109/L increase | 1.0 (0.9-1.1) | .546 | 1.0 (0.9-1.2) | .725 | 0.9 (0.8-1.1) | .336 | 1.0 (0.9-1.1) | .64 | ||||

| Platelet count per 1 × 109/L increase | 1.0 (1.0-1.0) | .235 | 0.9 (0.6-1.4) | .643 | 1.0 (1.0-1.0) | .477 | 1.0 (1.0-1.0) | .38 | ||||

| Hemoglobin level per 1 g/dL increase | 0.73(0.54-0.97)* | .034* | 0.47 (0.28-0.79)* | .004* | 0.67 (0.46-0.98)* | .048* | 0.77 (0.60-1.00)* | .050* | ||||

| MCV per (fL) increase | 1.04 (0.99-1.08) | .053 | 1.05 (0.98-1.12) | .149 | 1.02 (0.98-1.07) | .292 | 1.03 (0.99-1.07) | .069 | ||||

| Reticulocyte count per 1 × 109/L increase | 1.005 (1.002-1.008) | .001* | 1.005 (1.000-1.010) | .069 | 1.0 (1.0-1.0) | .641 | 1.003 (1.000-1.005)* | .028* | ||||

| HbF per 1% increase | 1.02 (0.98-1.06) | .279 | 0.98 (0.91-1.06) | .688 | 0.97 (0.92-1.03) | .265 | 1.0 (1.0-1.0) | .94 | ||||

| LDH per IU/mL increase | 2.73 (1.14-5.64)* | .024* | 7.31 (1.91-27.92)* | .004* | 2.06 (0.72-5.88) | .177 | 3.31 (1.61-6.83)* | .001* | ||||

| Multivariate analysis | ||||||||||||

| G6PD deficiency | 2.3 (1.0-5.2)* | .046* | 3.6 (1.2-11.0)* | .024* | ||||||||

| Absence of α-thalassemia | 2.5 (1.04-5.0)* | .041* | ||||||||||

| Hemoglobin level per 1 g/dL decrease | 1.7 (1.1-2.8)* | .011* | ||||||||||

| Reticulocyte count per 1 × 109/L increase | 1.005* (1.002-1.008)* | <.001* | 1.003 (1.000-1.006)* | .04* | ||||||||

| LDH per IU/mL increase | 4.9 (1.2-19.7)* | .027* | 2.78 (1.33-5.81)* | .007* | ||||||||

Shown are the results of the Cox regression univariate and multivariate analysis performed in to assess baseline predictive factors associated with abnormal TCD, abnormal MRA (stenosis), silent stroke, and those associated with the cumulative cerebral risk.

For this analysis, biologic parameters were (as in the Table 1) the average of those obtained at baseline after the age of 12 months and before the age of 3 years, a minimum of 3 months away from a transfusion, 1 month from a painful episode, and before any intensive therapy (hydroxyurea, transfusion program or stem cell transplantation).

CI indicates confidence interval; HbF, fetal hemoglobin; HR, hazard ratio; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; MRA, magnetic resonance angiography; and SCA, sickle cell anemia.

Statistically significant.

Abnormal TCD

Multivariate Cox model analysis in the 217 SCA patients showed that G6PD deficiency (HR 2.3, 95% CI 1.0-5.2; P = .046), absence of α-thalassemia (HR 2.5, 95% CI 1.04-5.0; P = .041), and baseline reticulocytes count (HR 1.005 per 1 × 109/L increase, 95% CI 1.002-1.008, P < .001) were significant independent predictive factors for abnormal TCD.

Stenosis

In the 132 patients who underwent MRI/MRA, multivariate Cox model analysis showed that G6PD deficiency (HR 3.6, 95% CI 1.2-11.0; P = .024) and baseline lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level (HR 4.9 per 1 IU/mL increase, 95% CI 1.2-19.7; P = .027) remained significant and an independent predictive factors for stenosis.

Silent strokes

The multivariate Cox model retained only a low baseline hemoglobin level (HR 1.75 per 1 g/dL decrease, 95% CI 1.14-2.78; P = .011) as significant predictive factor for silent strokes.

Cerebral vasculopathy

When taking into account all cerebral vasculopathy (strokes, abnormal TCD, stenosis, or silent strokes), the multivariate Cox model retained baseline reticulocytes count (HR 1.003 per 1 × 109/L increase, 95% CI 1.000-1.006, P = .04) and LDH level (HR = 2.78 per 1 IU/mL increase, 95% CI 1.33-5.81; P = .007) as independent predictive factors.

Cerebral vasculopathy outcomes and intensive therapies

One hundred nine (43 girls, 66 boys) of the 217 patients required intensification at the median age of 3.4 years (range, 0.6-13.7 years). Eighty-six were placed on chronic transfusion for splenic sequestrations (n = 16), frequent VOC and/or ACS (n = 27), and abnormal TCD (n = 41/45; 2 patients returned to Africa after the first transfusion and 2 with TCD conversion from abnormal to conditional after 3 transfusions did not receive long-term transfusions because of parental refusal). No first stroke or relapse of high velocities were observed during the 162 patient-years on chronic transfusion program; however, in patients with a history of abnormal TCD and no TCD normalization on chronic transfusion, 4 developed stenosis, and 1 had a silent stroke (0.62/100 patient-years).

Hydroxyurea was prescribed to 54 patients who all had normal TCD/MRA at hydroxyurea initiation. Indications were frequent VOC and/or ACS (n = 37), severe anemia with baseline-hemoglobin level lower than 7 g/dL (n = 4), and normalized TCD on transfusion program with normal MRA findings (n = 13). Biologic parameters at the start of hydroxyurea and during treatment are shown in Table 4. During the 225 patient-years on hydroxyurea, 2 patients with normal TCD at hydroxyurea initiation subsequently developed abnormal TCD and were placed on chronic transfusion. Thirteen patients with normal MRA findings and a history of abnormal TCD who had normalized on chronic transfusion were subsequently treated with hydroxyurea; 3 of 13 had relapsed abnormal TCD with appearance of stenosis and were permanently placed on chronic transfusion, whereas 10 are still on hydroxyurea. MRI/MRA, performed in 47 patients on hydroxyurea, revealed silent strokes in 14 patients; 7 had evidence of silent strokes before hydroxyurea initiation and the 7 others had their MRI/MRA performed after hydroxyurea initiation, making it impossible to determine the timing of silent stroke occurrence.

Blood parameters in 54 patients before and after HU therapy

| . | Before HU° . | On HU°° . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) . | Mean (SD) . | ||

| Age, y | 6.4 (3.6) | 9.5 (4.0) | |

| WBC count, ×109/L | 14.6 (5.8) | 9.1 (3.8) | <.001 |

| Neutrophil count, ×109/L | 7.3 (4.2) | 4.6 (3.3) | <.001 |

| Platelet count, ×109/L | 405.6 (118.9) | 320.1 (99.4) | <.001 |

| Hemoglobin level, g/dL | 7.5 (0.9) | 8.7 (1.1) | <.001 |

| Hematocrit, % | 22.4 (3.0) | 26.0 (3.5) | <.001 |

| MCV, flt | 80.4 (9.5) | 97.6 (13.7) | <.001 |

| Reticulocyte count, ×109/L | 303.4 (99.9) | 183.5 (86.8) | <.001 |

| HbF, % | 8.5 (5.0) | 16.4 (8.4) | <.001 |

| LDH, IU/L | 1090 (361) | 801 (313) | <.001 |

| Total bilirubin, μmol/L | 53.9 (38.4) | 42.1 (25.9) | .068 |

| . | Before HU° . | On HU°° . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) . | Mean (SD) . | ||

| Age, y | 6.4 (3.6) | 9.5 (4.0) | |

| WBC count, ×109/L | 14.6 (5.8) | 9.1 (3.8) | <.001 |

| Neutrophil count, ×109/L | 7.3 (4.2) | 4.6 (3.3) | <.001 |

| Platelet count, ×109/L | 405.6 (118.9) | 320.1 (99.4) | <.001 |

| Hemoglobin level, g/dL | 7.5 (0.9) | 8.7 (1.1) | <.001 |

| Hematocrit, % | 22.4 (3.0) | 26.0 (3.5) | <.001 |

| MCV, flt | 80.4 (9.5) | 97.6 (13.7) | <.001 |

| Reticulocyte count, ×109/L | 303.4 (99.9) | 183.5 (86.8) | <.001 |

| HbF, % | 8.5 (5.0) | 16.4 (8.4) | <.001 |

| LDH, IU/L | 1090 (361) | 801 (313) | <.001 |

| Total bilirubin, μmol/L | 53.9 (38.4) | 42.1 (25.9) | .068 |

HbF indicates fetal hemoglobin; HR, hazard ratio; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; and WBC, white blood cell count.

Twenty-six patients (9 girls, 17 boys) underwent myeloablative genoidentical stem cell transplantation. Eighteen patients received bone marrow, and 8 had cord blood as the stem cell source. Indications were cerebral vasculopathy in 14 patients (no overt stroke, stenosis in 5, including 2 with silent strokes and silent strokes with normal MRA findings in 9) and frequent VOC and/or ACS in 12 patients. Engraftment was successful in 25 of 26. In addition, none of the transplanted patients experienced a stroke, developed increased velocities, or presented with new ischemic lesions during the 98 patient-years' follow-up. Of note, velocities decreased quickly after stem cell transplantation, even in the 2 patients who still had abnormal TCD on chronic transfusion.27

Adverse effects of treatment

No viral contamination was observed in patients on chronic transfusion, but 3 patients required central venous access, and 12 developed alloimmunization (8 anti-M, 2 anti-Lea, 1 anti-JkB, and 1 anti-P1), although chronic transfusion remained possible. Ferritin levels > 1000 ng/mL, indicating iron overload after 1-2 years' transfusions, required exchange transfusions or chelation; 7 patients received deferoxamine and were secondarily switched to deferasirox, whereas 44 patients were directly chelated with deferasirox. Transitory gastrointestinal disorders were observed in 8 patients, and 2 patients had increased alanine aminotransferase values > 5 × ULN. Two patients were switched to deferiprone because of persistent nausea. MRI evaluation of liver iron concentration (LIC) was performed in the 25 patients with the greatest ferritin levels. The LIC was greater than normal (> 36 μmol/gdw) in 23 patients and the median (range) LIC was 220 μmol/gdw (5-529), but none of the patients had cardiac T2* < 20 milliseconds. All had normal ejection fraction, and no endocrine dysfunction was observed in this cohort. Iron-loaded patients who were transplanted had successful iron removal via phlebotomies after transplant. During hydroxyurea treatment, only 4 patients experienced transitory decrease of neutrophils or reticulocytes that required hydroxyurea interruption for 1-2 weeks.

No death or graft-versus-host disease ≥ grade 2 was observed after stem cell transplantation. At censure, 8 of 26 transplanted patients were older than 14 years of age (3 girls, 5 boys). All boys had normal levels of testosterone, follicle-stimulating hormone, or luteinizing hormone and normal puberty development. One girl, who was pubertal at transplantation, developed ovarian failure requiring hormonal treatment whereas the 2 others, transplanted before age 8 years, had spontaneous puberty with normal estradiol, follicle-stimulating hormone, and luteinizing hormone levels.28

Discussion

In developed countries, the survival of children with SCA is no longer a major problem because of early detection of the disease and high standard of care.1-8,10,29,30 The mortality of 0.25/100 patient-years and survival estimate of 97.5% (95% CI 93.4%-99.1%) by age 18 years in this SCA newborn cohort (1988-2007) seem equivalent to those of the most recently reported cohorts with 0.52 deaths/100 patient-years and 93.9% survival estimate (95% CI 90.3%-96.2%) for the Dallas cohort (1983-2007),30 and 0.27/100 patient-years and 99.0% (95% CI 93.2%-99.9%) survival estimate by age 20 for the East London cohort (1982-2005).11 The recent Dallas report also showed an improvement of survival to age 5 years since the introduction of the Prevnar vaccine in 2000.30 The trends to better survival observed in the cohorts from the United Kingdom and France may be explained by maintenance of prophylactic penicillin after age 5 years and an easier access to care attributable to universal medical coverage.

In contrast, morbidity, particularly the risk of strokes, remains a major concern in SCA children; nevertheless, the overall incidence and the cumulative risk of strokes by age 18 years are lower in this newborn cohort than in those previously reported,9-11 as illustrated in Table 5. This may be attributable to the fact that the 2004 report of the Dallas newborn cohort10 essentially reflects the pre-TCD era (1983-2002), and that, in the United Kingdom newborn cohort,11 the first TCD was only performed at the mean age of 6.4 years and transfusion was not systematically initiated after the occurrence of an abnormal TCD. Thus, the lower cumulative risk of strokes by age 18 years in our cohort suggests a favorable outcome of early TCD screening and intensive therapy.

Comparative stroke risk in different cohorts

| . | CSSCD . | Jamaica . | Dallas . | London, United Kingdom . | Créteil, France . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood 1998 . | J Pediatr 1992 . | Blood 2004 . | Haematologica 2007 . | Newborn Cohort . | |

| Infant Cohort . | Newborn Cohort . | Newborn Cohort . | Newborn Cohort . | ||

| Enrollment period | 1978-1988 | 1983-2002 | 1983-2005 | 1988-2007 | |

| SS patients | SS patients | SS/Sb0 patients | SS patients | SS/Sb0 patients | |

| Number of patients included in the cohort | 2436 | 310 | 448 | 180 | 217 |

| Patient-years of follow-up | 1781 | 3571 | 1542 | 1609 | |

| Number of first strokes before age 20 years | 51 | 17 | 30 | 7 | 3 |

| First stroke incidence/100 patient-years | 0.61 | ||||

| Up to 16 years | 0.3 (95% CI 0.1-0.8) | ||||

| Up to 18 years | 0.85 | 0.19 (95% CI 0.04-0.5) | |||

| KM estimate of stroke risk by age | |||||

| 4 | 3.7% (95% CI 1.7%-5.7%) | ||||

| 5 | 0.7% (95% CI 0.1%-5.0%) | 1.9% (95% CI 0.6%-5.9%). | |||

| 6 | 5.7% (95% CI 3.3%-8.2%) | ||||

| 10 | 8.4% (95% CI 5.5%-11.6%) | 2.7% (95% CI 0.9%-8.3%) | 1.9% (95% CI 0.6%-5.9%). | ||

| 14 | 7.8% | 11.5% (95% CI 7.3%-15.7%) | 1.9% (95% CI 0.6%-5.9%). | ||

| 15 | 4.3% (95% CI 1.5%-11.4%) | ||||

| 18 | 11.5% (95% CI 7.3%-15.7%) | 1.9% (95% CI 0.6%-5.9%). | |||

| 20 | 11% | 12.8% (95% CI 4.8%-31.3%) |

| . | CSSCD . | Jamaica . | Dallas . | London, United Kingdom . | Créteil, France . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood 1998 . | J Pediatr 1992 . | Blood 2004 . | Haematologica 2007 . | Newborn Cohort . | |

| Infant Cohort . | Newborn Cohort . | Newborn Cohort . | Newborn Cohort . | ||

| Enrollment period | 1978-1988 | 1983-2002 | 1983-2005 | 1988-2007 | |

| SS patients | SS patients | SS/Sb0 patients | SS patients | SS/Sb0 patients | |

| Number of patients included in the cohort | 2436 | 310 | 448 | 180 | 217 |

| Patient-years of follow-up | 1781 | 3571 | 1542 | 1609 | |

| Number of first strokes before age 20 years | 51 | 17 | 30 | 7 | 3 |

| First stroke incidence/100 patient-years | 0.61 | ||||

| Up to 16 years | 0.3 (95% CI 0.1-0.8) | ||||

| Up to 18 years | 0.85 | 0.19 (95% CI 0.04-0.5) | |||

| KM estimate of stroke risk by age | |||||

| 4 | 3.7% (95% CI 1.7%-5.7%) | ||||

| 5 | 0.7% (95% CI 0.1%-5.0%) | 1.9% (95% CI 0.6%-5.9%). | |||

| 6 | 5.7% (95% CI 3.3%-8.2%) | ||||

| 10 | 8.4% (95% CI 5.5%-11.6%) | 2.7% (95% CI 0.9%-8.3%) | 1.9% (95% CI 0.6%-5.9%). | ||

| 14 | 7.8% | 11.5% (95% CI 7.3%-15.7%) | 1.9% (95% CI 0.6%-5.9%). | ||

| 15 | 4.3% (95% CI 1.5%-11.4%) | ||||

| 18 | 11.5% (95% CI 7.3%-15.7%) | 1.9% (95% CI 0.6%-5.9%). | |||

| 20 | 11% | 12.8% (95% CI 4.8%-31.3%) |

CI indicates confidence interval; and CSSCD, Cooperative Study of Sickle Cell Disease.

The STOP-I study12,13 clearly demonstrated that an abnormal TCD was predictive of stroke risk (10% per year) in SCA patients and that chronic transfusion reduced this risk by 92%.13 The current recommendation, at least in the United States, is to initiate a transfusion program after 2 abnormal TCD screenings, the repeat screening being obtained less than 1 month away from the first TCD. In our center, we decided in 2001 to transfuse patients as soon as an abnormal TCD was detected. This decision came about, not only because we observed a stroke just before the repeat TCD but also because exposure to high velocities themselves results in a higher risk of stroke.18,31 As mentioned in “Methods,” we are mindful of preventing unnecessary long-term transfusion programs, and an abnormal TCD associated with an unusually low hemoglobin level on the day of the TCD is treated by a single transfusion as a protective measure before the TCD is repeated 3 months later.

In our cohort, 45 patients had an abnormal TCD, providing 149 patient-years after abnormal TCD with a potential risk of 15 strokes. In fact, only 1 patient had a stroke, just before the confirmatory TCD and the start of the transfusion program. Thus, 14 strokes were avoided by the use of intensive therapy in this newborn cohort. The cost of a transfusion program with chelation has been estimated to be approximately $40 000/year32 for deferoxamine or €45 000/year for deferasirox,33 but a stroke requires not only life-long transfusions with chelation, but also rehabilitation costs of $40 000/year.34 Compliance to transfusions by families was good in our center, and no severe complications occurred, suggesting that the STOP-I recommendations of TCD screening and transfusion therapy are both efficacious and safe in the “real world,” that is, outside of a randomized controlled trial. Two strokes may have been avoided; one, by performing a transfusion as soon as the first abnormal-TCD was detected in 1 patient, and two, by performing MRI/MRA in the patient with unavailable temporal window for TCD assessment. It is important to keep in mind that iron overload is clearly associated with chronic transfusion programs, although the risk of organ toxicity is less in SCA than in thalassemia. Although iron overload can be seen in young patients, the use of exchange transfusions when patients are older and the current significant advances in monitoring transfusion hemochromatosis and in chelation therapy greatly reduce the risk of iron-related morbidity in later years.

The STOP-II study35 showed that transfusion program could not be stopped safely, even in patients with normalized velocities and normal MRA. Here, chronic transfusion was stopped in patients with normalized velocities, normal MRA (no stenosis), and no previous stroke but was replaced by hydroxyurea.18 No stroke occurred in these patients receiving hydroxyurea, suggesting that chronic transfusion can be safely stopped in a subset of patients. Hydroxyurea, however, can have deleterious effects,26 particularly in patients with cerebral vasculopathy.

In the SWiTCH (Stroke With Transfusions Changing to Hydroxyurea) study, which involved children 5 to 18 years of age with a history of strokes and transfusions for at least 18 months, the authors randomized the continuation of a transfusion program combined with oral deferasirox (n = 66) versus the initiation of hydroxyurea and iron removal by phlebotomy (n = 67). This study was recently terminated early by its Data and Safety Monitoring Board and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute because phlebotomy did not reduce liver iron better than deferasirox therapy. The Data and Safety Monitoring Board also noted that a significantly greater number of strokes occurred in the hydroxyurea/phlebotomy arm than in the transfusions/deferasirox arm (7 vs 0).36 Although the analysis of the study has not been published yet, one can speculate that the combination of hydroxyurea and phlebotomy was not as effective as transfusions and deferasirox in preventing the reoccurrence of stroke. This and the fact that no study so far has proven that hydroxyurea prevents strokes in patients with abnormal TCD, regardless of the MRA status, clearly indicate that switching patients with abnormal TCD to hydroxyurea after TCD has normalized on transfusions can occur only in those patients with normal MRA and under specific controlled conditions, such as clinical trials or established procedures of care that require trimestrial TCD assessment and immediate reinstatement of transfusions in case of abnormal TCD relapse. Transfusions also were stopped in the 5 transplanted patients with macrovasculopathy (abnormal TCD and/or stenoses). Genoidentical stem cell transplantation is the only procedure that offers a 95% cure28 and allows safe interruption of transfusions in patients with macrovasculopathy. Its cost (€76 237 in France)37 is approximately equivalent to 2 years of a transfusion program with chelation. These data argue that stem cell transplantation should be discussed early and systematic sibling cord blood storage encouraged.

The cumulative risk of abnormal TCD was 29.6% (95% CI 22.8%-38.0%) by age 14 years in our cohort, which appears greater than the 9.2%-9.7% prevalence previously reported in patients screened in 1995-1997,13,22 which raises the question of potential overdiagnosis in this cohort. These previous reports used prevalence and not KM estimates of cumulative risk as here, making comparison difficult. The greater rate of abnormal TCD in this series is unlikely to be attributable to false-positive results because no angle correction was used in our study, but it may in part be explained by having all TCD performed by one single expert with 18 years' experience. An additional explanation may be a greater severity of disease in this cohort compared with the Cooperative Study of Sickle Cell Disease cohort38 (hemoglobin: 7.8 vs 9.0 g/dL, leukocyte count: 14.2 vs 13.7 × 109/L, Car/Car haplotype: 43.8% vs 5.9%).

The greatest velocities were observed in patients between the ages of 3 and 6 years, which is in accordance with the known greatest incidence of strokes between age 2 and 5 years.9 No first abnormal-TCD occurred after age 9 years. Age younger than 4 years was a significant risk factor for conversion from conditional to abnormal TCD, which is in accordance with the STOP study39 but not with another report.40 Our results suggest that patients with conditional TCD, particularly younger ones, should be followed by trimestrial instead of yearly TCD. It is worth noting that 4 patients with abnormal TCD developed stenoses secondarily, despite being on chronic transfusion, confirming that abnormal TCD usually precedes stenosis occurrence.18,19

Silent strokes are another serious manifestation of cerebral vasculopathy in SCA patients, compromising cognitive functioning.22,41 The cumulative risk of silent strokes in our patients was high and did not exhibit a plateau (Figure 3C). Earlier studies by us and others reported a prevalence of 15%-17%22,41,42 or 21.8% at the mean age of 8.2 years.43 Although the use of KM estimates of cumulative risk versus prevalence renders comparison difficult, technical improvements allowing the identification of lesions previously undetected may also be at play. The most recent retrospective study found a prevalence of silent strokes of 27.7% (95% CI 17.3%-40.2%) in SS children assessed before age 6 years.44 This study and ours support that silent strokes may begin early in life, as previously suggested.45,46 The high risk of silent strokes observed in our cohort shows that early macrovasculopathy detection by TCD is not sufficient for the primary prevention of silent strokes and suggests the need for more preventive interventions.

We confirm in this cohort followed since birth our previous results demonstrating that G6PD-deficiency and absence of α-thalassemia are independent predictive factors for abnormal TCD.47 Despite a trend toward more severe anemia in patients with G6PD deficiency (baseline hemoglobin: 7.6 ± 1.3 vs 8.1 ± 1.2 g/dL, P = .13), no significant difference was found in the hemolytic rate (reticulocyte count and LDH) of SCA patients with or without G6PD deficiency. This finding suggests that G6PD deficiency increases risk by a mechanism other than hemolysis. G6PD has long been considered as an antioxidant enzyme in erythrocytes. Accumulating data now indicate that G6PD has a similar role in vascular cells under conditions of increased production of reactive oxygen species.48 Our findings of an association between G6PD deficiency and abnormal TCD and stenoses seem relevant because increased oxidative stress and decreased nitric oxide levels have also been reported in G6PD-deficient endothelial cells.49 An association between G6PD deficiency and the risk of abnormal TCD was not found in a United Kingdom cohort50 ; however, several differences between the studies could explain this discrepancy, as we pointed out in our rebuttal.50 First, abnormal TCD was defined as TAMMX > 169 in the United Kingdom cohort and not as ≥ 200 cm/s, and second, the follow-up was shorter. In addition, we also show that biologic parameters recorded at baseline between 1 and 3 years of age have an important prognostic value, given that independent predictive factors for cerebral vasculopathy risk were high reticulocyte counts and high LDH levels, demonstrating the impact of hemolysis as a risk factor for cerebral vasculopathy.

This is a longitudinal prospective observational cohort study with no control group and no prospective computation of sample size to control for type I and type II errors. Thus, determination of effectiveness or assessment of net benefits cannot be inferred from such study, contrary to randomized controlled trials. Our analysis was limited to hematologic factors, but genetics, thrombophilia, vascular biology, oxidative stress, and inflammation, all factors that were not assessed here, may have played a role in determining the outcomes in this cohort. Nonetheless, this study offers the advantages of long-term and accurate data collection in a cohort from only one referral center at which management care and procedures are standardized. Although causality cannot be established, the associations determined in this study could be the basis for further controlled studies.

It could be argued that the results obtained here cannot be generalized. It is possible that results may not be reproduced in centers outside of countries with easy access to medical care, where compliance to treatment may not be as good as it was in this cohort, and repeated check-ups may not be financially possible. In addition, a team approach and established procedures of standard of care are necessary to adequately monitor patients. Yet, we think that adopting management strategies such as early TCD screening, extensive yearly checkup, and intensive therapy may improve results in any center.

In conclusion, this study is the first to report in a newborn cohort the long-term benefits of strategies adapted from the STOP-I trial. The reduction in stroke risks, avoiding severe motor and cognitive deficiencies, results not only in significant improvement in patients' lives but also benefits society as a whole as patients are potentially able to better integrate socially and professionally. However, the 50% cumulative cerebral risk suggests the need for more preventive interventions.

Presented in part at the 50th annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, San Francisco, CA, December 6-9, 2008.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients, their parents, and all the nurses and physicians at the CHIC and the SCT St-Louis and Mondor units who all contributed to decreasing the number of strokes.

This work was supported in part by an institutional grant “Program Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique” (IDF05001) from the French Ministry of Health.

Authorship

Contribution: F.B. designed and performed the research, collected, performed the statistical analyses and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript; S.V. performed transcranial Doppler and MRI/MRA and analyzed and interpreted data; S.C. performed and supervised the statistical analyses; F.B., C.A., A.K., I.H., L.C., E. Leveillé, E. Lemarchand, E. Lesprit, I.A., N.M., F.M., S.L., S.B., P.R., and C.D. participated in the management of patient care; S.V., S.C, M.T., and M.K. helped write the manuscript; M.K., C.F., and G.S. participated in the management of patients undergoing transplantation; F.G and J.B. organized the newborn screening; and all authors critically reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Françoise Bernaudin, Pédiatrie, Centre de Référence des Syndromes Drépanocytaires Majeurs, Hôpital Intercommunal de Créteil, 40 avenue de Verdun, 94010 Créteil, France; e-mail: francoise.bernaudin@chicreteil.fr.