Abstract

The activation of Fli-1, an Ets transcription factor, is the critical genetic event in Friend murine leukemia virus (F-MuLV)–induced erythroleukemia. Fli-1 overexpression leads to erythropoietin-dependent erythroblast proliferation, enhanced survival, and inhibition of terminal differentiation, through activation of the Ras pathway. However, the mechanism by which Fli-1 activates this signal transduction pathway has yet to be identified. Down-regulation of the Src homology 2 (SH2) domain-containing inositol-5-phosphatase-1 (SHIP-1) is associated with erythropoietin-stimulated erythroleukemic cells and correlates with increased proliferation of transformed cells. In this study, we have shown that F-MuLV–infected SHIP-1 knockout mice display accelerated erythroleukemia progression. In addition, RNA interference (RNAi)-mediated suppression of SHIP-1 in erythroleukemia cells activates the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI 3-K) and extracellular signal-regulated kinase/mitogen-activated protein kinase (ERK/MAPK) pathways, blocks erythroid differentiation, accelerates erythropoietin-induced proliferation, and leads to PI 3-K–dependent Fli-1 up-regulation. Chromatin immunoprecipitation and luciferase assays confirmed that Fli-1 binds directly to an Ets DNA binding site within the SHIP-1 promoter and suppresses SHIP-1 transcription. These data provide evidence to suggest that SHIP-1 is a direct Fli-1 target, SHIP-1 and Fli-1 regulate each other in a negative feedback loop, and the suppression of SHIP-1 by Fli-1 plays an important role in the transformation of erythroid progenitors by F-MuLV.

Introduction

The progression of cancer is a multistep process in which oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes mediate changes in gene expression required for malignant transformation. Transcription factors, often described as oncogenes or tumor suppressor genes, play a pivotal role within signal transduction pathways governing cellular proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis.1

In Friend murine leukemia virus (F-MuLV)-induced erythroleukemia, the transcription factor fli-1 is activated as a result of proviral integration. A proto-oncogene and member of the Ets family of transcription factors, fli-1 plays a critical role in normal development, hematopoiesis and oncogenesis.2-6 Accordingly, a recent study from our group, and that of another laboratory, has demonstrated that Fli-1 inhibition suppresses growth and induces cell death in murine and human erythroleukemias.7,8 Fli-1 overexpression in erythroblasts blocks erythroid differentiation that is associated with activation of the Shc/Ras pathway in response to erythropoietin (Epo) stimulation.9 The Src homology 2 (SH2) domain-containing inositol-5-phosphatase-1 (SHIP-1) is associated with phosphorylated Shc in Epo-stimulated erythroleukemic cells,9 and correlates with increased proliferation of transformed erythroid cells.10 Because SHIP-1 is involved in the regulation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase/mitogen-activated protein kinase (ERK/MAPK) and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI 3-K) signaling pathways,11,12 we hypothesized that Fli-1 may promote Epo-induced proliferation, and activation of the above mentioned pathways, in part, through regulation of SHIP-1.

SHIP-1 plays a role in the activation and proliferation of myeloid cells, macrophages, and mast cells. This phosphatase also negatively regulates c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK),13 and nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) activity.14 SHIP-1 is expressed exclusively in hematopoietic cells and developing spermatogonia and is activated after cytokine, growth factor, or immunoreceptor activation in hematopoietic cells.12,14,15 SHIP-1 is expressed in mature T cells, granulocytes, monocytes/macrophages, mast cells, and platelets.16 Interestingly, it has been documented that SHIP-1 expression is turned off during erythropoiesis, specifically in TER119+ erythroid cells.15 Expression of a short form of SHIP-1 (termed s-SHIP) modulates the activation threshold of primitive stem cells.17,18 SHIP-1 knockout mice are viable but have a shortened lifespan.11 These mice overproduce granulocytes/macrophages, develop splenomegaly, display extramedullary hematopoiesis, exhibit increased numbers of erythroid progenitors, and suffer from massive myeloid infiltration of the lungs.11,19

SHIP-1 is involved in various leukemias,11,20-23 particularly, it acts as a negative regulator in chronic myelogenous leukemia and other leukemias containing the BCR-ABL fusion protein.22 We have used SHIP-1 knockout mice in this study to show that the loss of this phosphatase accelerates the progression of erythroleukemia induced by F-MuLV. We have shown that Fli-1 transcriptionally represses SHIP-1 expression during F-MuLV–induced erythroleukemias by binding to the Ets consensus DNA binding sequence located within the SHIP-1 promoter. Moreover, we demonstrated that fli-1 is a downstream effector of the PI 3-K pathway suggesting the possibility of a negative feedback loop in which SHIP-1 and Fli-1 regulate each other.

Methods

Cell culture

Details may be found in supplemental Methods (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Ectopic expression of Fli-1

The MigR1 Fli-1, or empty vector control plasmid, MigR1, was triple-transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) into 293T cells, following the manufacturer's protocol. The vesicular stomatitis virus G glycoprotein (VSVG)-expressing vector as well as the gag and pol virus packaging signals were provided by D.L.B. Viral supernatant was collected 48 hours after transfection. DP17-17 cells (2.5 × 106) were infected with virus and incubated 16 hours with virus in the presence of polybrene (8 μg/mL final concentration) as previously described.7

Immunoblotting

Cells were lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (0.5% Nonidet P-40, 50mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 120mM NaCl, 50mM NaF, plus 1mM Na3VO4, 10 g/mL aprotinin, 100 g/mL leupeptin, and 10mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF]). Lysates (40 μg) were fractioned by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Immobilon-P; Millipore). The following antibodies were used: SHIP-1, Fli-1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology); β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich); PTEN, phospho-p44/42 MAPK, phospho-Akt (Ser473), Akt (Cell Signaling); MAPK (BD Transduction Laboratories); goat anti–mouse, and goat anti–rabbit IgG horseradish peroxidase (HRP)–conjugated (Promega).

SHIP-1+/− mice and F-MuLV inoculation

SHIP-1+/− mice have been previously described.12,24 All mouse experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Sunnybrook Health Sciences Center. Genotyping polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) were performed with 50 ng DNA. Primers; SHIP-1, forward: 5′-CATGCCTTTGGCCTATTCAC-3′, reverse: 5′-GGCTCTGGAAAGTAGCTCCTCT-3′; neomycin, forward: 5′-ATTCGACCACCAAGCGAAAC-3′, reverse: 5′-CGTAGCTCCAATCCTTCCATTC-3′. Viral supernatants from NIH 3T3 cells containing F-MuLV clone 5725 were harvested and frozen at −80°C. Newborn mice were inoculated by intraperitoneal injections with 100 μL, 2800 focus forming units, F-MuLV clone 57 within 48 hours of birth. Tail blood samples were collected using a 200-μL EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) –coated capillary tube (Drummond Scientific). Hematologic analysis performed at the Toronto Center for Phenogenomics (TCP) using the COULTER AC·T diff Analyzer. Hematocrit values were measured by tail blood collection in 200-μL heparinized capillary tubes (Drummond Scientific), centrifuged at 100g for 10 minutes, and compared using a hematocrit gauge.

RNA interference

The SHIP-1 small interfering RNA sequence 5′-GGAAGTCATCAGGACTCTGCA-3′,26 was used to design small hairpin RNA (shRNA) oligonucleotides synthesized by Sigma Genosys Canada. SHIP-1 shRNA oligonucleotides were cloned into pSIREN RetroQ ZsGreen (Clontech, Takara Bio) using T4 DNA ligase (New England Biolabs). Control vector contains a shRNA sequence of the same nucleotide composition as SHIP-1 shRNA, lacking sequence homology to the genome. pSIREN retroviral vectors were triple-transfected into 293T cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's protocol. Viral supernatant was collected 48 hours after transfection and concentrated by ultracentrifugation at 112 700g for 2 hours. HB60-5 cells were incubated 24 hours with concentrated virus, in the presence of polybrene (8 μg/mL final concentration), as described previously.7 Cells were sorted using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) based on green fluorescence (ZsGreen) expression 2 days after transduction. After 10 days in culture, cells were sorted based on high intensities of green fluorescence a second time, termed SHIP-1 shRNA-dbl sort. Clone 8D was isolated by performing limited dilutions of SHIP-1 shRNA-dbl sort cells.

RNA extraction and Northern blotting

Total RNA was extracted from cells using Trizol (Gibco, Invitogen), according to the manufacturer's protocol. RNA (20 μg) was dissolved in 2.2M formaldehyde, denatured at 65°C for 15 minutes, separated by electrophoresis in 1% agarose gels containing 0.66M formaldehyde, and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Zeta-Probe; Bio-Rad Laboratories). The membrane was hybridized with radioactively labeled probe, 2 × 106 cpm/mL α-32P dCTP (Perkin Elmer), prepared by excising a 2.2-kb EcoRI fragment from the PB1 plasmid.

Cellular differentiation and proliferation assays

HB60-5-shRNA expressing cells were induced to differentiate in the presence of 1 U/mL Epo for 96 hours, as described elsewhere.10 Cells were harvested and subjected to Northern blot analysis (see previous subsection). Cells (1 × 104) plated in triplicate were removed at 24 intervals, and cellular proliferation was measured by performing trypan-blue exclusion assay.

SHIP-1 luciferase reporter assay

A 988-bp region of the SHIP-1 promoter was amplified using PCR (forward: 5′-GTGCGTGCATGTGTGTGTAG-3′, reverse: 5′-AATTGCCTCTGCTGCTCCTA-3′; genomic DNA isolated from a Balb/c mouse), and cloned into the luciferase pGL3-enhancer vector (Promega), designated pGL3-SHIP-1. A 2-bp mutation within the Ets binding site was created using the QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene), designated pGL3-mut-SHIP-1. Mutagenesis primers; forward: 5′-CTGAGTGCCTGAAACAGGTTGTCAGTCAGTTAAGCTG-3′, reverse: 5′-CAGCTTAACTGACTGACAACCTGTTTCAGGCACTCAG. All vectors were verified by sequencing at the TCAG facility (MaRS) using the ABI 3730XL sequencer. 293T cells, plated in triplicate, were transfected with the indicated amounts of DNA (0.2 μg of pGL3-SHIP-1 or pGL3-mut-SHIP-1, 0.2, 0.4, or 0.6 μg of MigR1-fli-1 and 0.01 μg of pRL-SV40 containing the Renilla luciferase gene) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's protocol. Cells were assayed 48 hours after transfection for luciferase activity using the Dual-Glo Luciferase Assay System kit (Promega).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation and quantitative PCR

CB3, HB60-5, and KH16 cells (1 × 108) were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Gibco, Invitrogen) twice, cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde in PBS at 37°C for 15 minutes, followed by the addition of 125 mM glycine for 5 minutes at room temperature. Fixed cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed in PBS, and incubated on ice for 50 minutes in swelling buffer (20mM HEPES [N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid], pH 7.9, 10mM KCl, 1mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 1mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 0.5mM PMSF, 0.1mM Na3VO4). Cells were broken by dounce homogenization, and nuclei were pelleted by brief centrifugation and resuspended in lysis buffer (10mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 140mM NaCl, 0.025% NaAzide, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, 1mM DTT, 0.5mM PMSF, 0.1mM Na3VO4, 1% deoxycholate), and sonicated for 3 minutes using a Branson 250 Sonifier, followed by centrifugation. Fragmented chromatin was precleared by incubation with protein A sepharose beads for 1 hour at 4°C. A 50-μL aliquot of chromatin was removed for the input control. Immunoprecipitations were performed overnight at 4°C with either 2 μg of Fli-1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or nonspecific normal rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG; Promega) antibody or without antibody (mock control). After immunoprecipitation, 120 μL of 20% protein A sepharose beads were added and incubation continued for 1 hour. Precipitates were washed once in 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2mM EDTA, 150mM NaCl, 20mM Tris-HCl; 4 times in 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2mM EDTA, 500mM NaCl, 20mM Tris-HCl; and once in 250mM LiCl, 1% NP-40, 1% deoxycholate, 1mM EDTA, 10mM Tris-HCl; 3 times in TE buffer (10mM Tris-HCl, 1mM EDTA), and extracted by adding 200 μL each 1% SDS and 100mM NaHCO3. NaCl (5M) was added to the eluates, final concentration 300mM, and heated at 65°C overnight to reverse cross-linking. DNA fragments were incubated with proteinase K at 50°C for 2 hours, purified with phenol chloroform, and resuspended in TE buffer. PCR was performed to amplify SHIP-1 on the recovered DNA. Primers; SHIP-1 S1 forward: 5′-CATGCCTTTGGCCTATTCAC-3′, S2 reverse: 5′-TGAGTGCCTGAAACAGGAAGT-3′; β-actin forward: 5′-TTCTACAATGAGCTGCCTGTG-3′, reverse: 5′-GGGGTGTTGAAGGTCTCAAA-3′; and Upstream-SHIP-1: 5′-CTGTCAGATGTTGTGTAGGGGC-3′, reverse: 5′-CCCAGCTAACCAGAACTACAGAAT-3′. The primers used for MDM2 amplification have been described previously.27 Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was quantified using the real-time PCR Qiagen QuantiFast SYBR green PCR kit (QIAGEN). Results are based on the relative proportion of input and chromatin precipitated by the Fli-1 or control IgG antibodies, where the input is equal to 1.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

Nuclear extract was isolated from CB3 cells using the method described in our previous publication.28 Oligonucleotide sequences; 5′-CCTGAAACAGGAAGTCAGTCAG-3′ (EBS1), 5′-CTATAATGAGGAAGTTCTGTGC-3′ (EBS2), 5′-CCCTCGTGTGGAACTTCGGCTG-3′ (EBS3), 5′-TGCGGCTTCCGGGACGGG-3′ (MDM2), 5′-CCTGAAACAGGTTGTCAGTCAG-3′ (MUT-EBS1). Single-stranded oligonucleotides were radioactively labeled [γ-32P]ATP (Perkin Elmer) with T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs). Single-stranded oligonucleotides were purified using NUCTrap probe purification columns (Stratagene), annealed to 2-fold excess cold complimentary oligonucleotides by boiling for 2 minutes and cooling at room temperature for 1 hour. For competition assays, 10-fold and 100-fold excess cold single-stranded oligonucleotides were added to the reaction. Fli-1 antibody (2 μL; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was added for the supershift assay. Samples were electrophoresed on a 5% acrylamide gel in 0.5 × Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) buffer. The gel was dried in a vacuum for 1 hour at 80°C.

Results

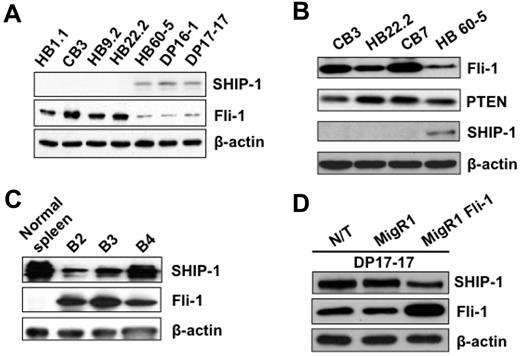

Negative correlation between SHIP-1 and Fli-1 expression in erythroleukemic cells

To fully understand the role of SHIP-1 in erythroleukemia cells, we first examined the expression of this phosphatase in erythroleukemic cell lines induced by various strains of Friend virus. As shown in Figure 1A-B, the expression of SHIP-1 protein is completely absent in F-MuLV-induced erythroleukemic cell lines overexpressing Fli-1, termed HB1.1, CB3, HB9.2, HB22.2, and CB7. However, SHIP-1 expression can be detected in HB60-5, DP16-1, and DP17-17 cells, which have acquired insertional activation at the spi-1/PU.1 locus,29 in lieu of fli-1.5,10 Further examination of these F-MuLV–induced erythroleukemia cell lines demonstrated that loss of SHIP-1 is exclusive to this group of cancer (data not shown), and this negative correlation does not occur between Fli-1 and PTEN, another inositol phosphatase that negatively regulates the PI 3-K/Akt pathway (Figure 1B).

SHIP-1 Fli-1 protein expression are inversely correlated in mouse erythroleukemia cells. SHIP-1, Fli-1 (A) and PTEN (B) expression levels in HB1.1, CB3, HB9.2, and HB22.2 cells, derived from spleens of F-MuLV–infected Balb/c mice, and HB60-5, DP16-1, and DP17-17 cells, derived from spleens of FV-P (SFFV-P + F-MuLV)-infected DBA/2J adult mice. SHIP-1 and Fli-1 expression levels in (C) the spleens of 8-week-old F-MuLV–infected mice (B2-B4). (D) Exogenous expression of Fli-1 in DP17-17 cells (MigR1 Fli-1) results in decreased expression of SHIP-1 compared with nontransduced (N/T) and empty vector control (MigR1) infected cells. β-Actin was used as a loading control for all samples.

SHIP-1 Fli-1 protein expression are inversely correlated in mouse erythroleukemia cells. SHIP-1, Fli-1 (A) and PTEN (B) expression levels in HB1.1, CB3, HB9.2, and HB22.2 cells, derived from spleens of F-MuLV–infected Balb/c mice, and HB60-5, DP16-1, and DP17-17 cells, derived from spleens of FV-P (SFFV-P + F-MuLV)-infected DBA/2J adult mice. SHIP-1 and Fli-1 expression levels in (C) the spleens of 8-week-old F-MuLV–infected mice (B2-B4). (D) Exogenous expression of Fli-1 in DP17-17 cells (MigR1 Fli-1) results in decreased expression of SHIP-1 compared with nontransduced (N/T) and empty vector control (MigR1) infected cells. β-Actin was used as a loading control for all samples.

The expression of SHIP-1 in primary F-MuLV-induced erythroleukemia cells was also examined. Spleens of F-MuLV-induced erythroleukemic mice, which have acquired fli-1 insertional activation,5 were isolated to determine the expression of Fli-1 and SHIP-1. Western blot analysis has revealed that the expression of SHIP-1 negatively correlates with that of Fli-1 in comparison to normal healthy controls (Figure 1C).

The aforementioned results suggested the ability of Fli-1 to negatively suppress the expression of SHIP-1. Therefore to further establish the negative relationship between Fli-1 and SHIP-1, exogenous expression of Fli-1 was introduced into the erythroleukemia cell line, termed DP17-17, expressing high levels of SHIP-1 and low levels of Fli-1 (Figure 1A-B). DP17-17 cells, transduced with either the empty vector control or Fli-1 expressing retrovirus, were sorted by flow cytometry based on green fluorescence 2 days after infection. The ectopic expression of Fli-1 results in the down-regulation of SHIP-1 expression, compared with the appropriate controls (Figure 1D). However, it is apparent that the level of SHIP-1 down-regulation is not proportionate to the level of exogenous Fli-1 expression. It is likely that the limited capacity of Fli-1 to inhibit SHIP-1 is due to the presence of other transcription factors that are involved in the regulation of SHIP-1.

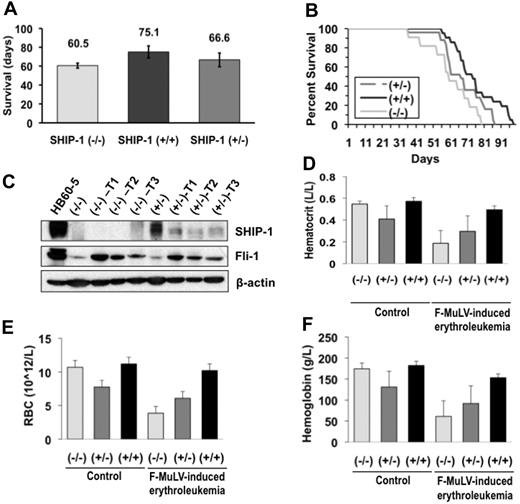

Acceleration of F-MuLV–induced erythroleukemia in SHIP-1 knockout mice

To address whether decreased levels of SHIP-1 provide an advantage to erythroleukemia development, SHIP-1 mutant mice were infected with F-MuLV. SHIP-1+/+, SHIP-1+/−, and SHIP-1−/− newborn mice, on a Balb/c background,12 were infected with F-MuLV, observed, and allowed to succumb to disease naturally. The mean survival rate in days is shown in Figure 2A. Data shows that SHIP-1−/−, SHIP-1+/−, and SHIP-1+/+ mice survived, on average, 60.5, 66.6, and 75.1 days, respectively, after F-MuLV infection. Wild-type mice survived from 56 to 98 days (median. 74 days), and SHIP-1−/− mice survived from 36 to 79 days (median, 60 days). SHIP-1+/− mice also displayed reduced survival, as they lived from 36 to 86 days (median, 67 days; Figure 2B). Logrank statistical analysis revealed a significant statistical difference between SHIP-1−/− and SHIP-1+/+ mice (P = .009). The difference between SHIP-1+/− and SHIP-1+/+ mice (P = .033) was also statistically significant; however, a greater significance was observed with SHIP-1−/− mice.

Acceleration of F-MuLV–induced erythroleukemia progression in SHIP-1 deficient mice. (A) Mean survival rate of F-MuLV–infected Balb/c mice. SHIP-1−/− n = 11; SHIP-1+/− n = 25; SHIP-1+/+ n = 21. (B) The survival rate of mice infected with F-MuLV as presented by a Kaplan-Meier survival curve. (C) Fli-1 and SHIP-1 protein expression in the spleens of 8-week-old SHIP-1−/− and SHIP-1+/− F-MuLV-induced erythroleukemic mice. (D) Mean hematocrit levels of 8-week-old mice infected with F-MuLV. (E) Mean RBC counts of 8-week-old mice infected with F-MuLV. (F) Mean hemoglobin levels in 8-week-old mice infected with F-MuLV. (D-F) n = 3.

Acceleration of F-MuLV–induced erythroleukemia progression in SHIP-1 deficient mice. (A) Mean survival rate of F-MuLV–infected Balb/c mice. SHIP-1−/− n = 11; SHIP-1+/− n = 25; SHIP-1+/+ n = 21. (B) The survival rate of mice infected with F-MuLV as presented by a Kaplan-Meier survival curve. (C) Fli-1 and SHIP-1 protein expression in the spleens of 8-week-old SHIP-1−/− and SHIP-1+/− F-MuLV-induced erythroleukemic mice. (D) Mean hematocrit levels of 8-week-old mice infected with F-MuLV. (E) Mean RBC counts of 8-week-old mice infected with F-MuLV. (F) Mean hemoglobin levels in 8-week-old mice infected with F-MuLV. (D-F) n = 3.

Fli-1 is activated through insertional mutagenesis in F-MuLV–induced erythroleukemias.5 SHIP-1+/+, SHIP-1+/−, and SHIP-1−/− tumors have also acquired fli-1 rearrangement, as determined by Southern blot analysis (data not shown). Consistent with specific insertional activation caused by F-MuLV (Figure 2C), Fli-1 protein levels are also elevated in SHIP-1−/− and SHIP-1+/− infected mice compared with uninfected controls. This result indicates that targeted deletion of SHIP-1 does not affect the incidence of erythroleukemia development. Because the progression of erythroleukemia in mice is associated with anemia,30 complete blood count (CBC) values, including hematocrit, red blood cell (RBC) counts, and hemoglobin were examined. CBC values were significantly lower in SHIP-1−/− than SHIP-1+/− and SHIP-1+/+ mice (Figures 2D-F). SHIP-1+/− mice also displayed lower CBC values compared with those of SHIP-1+/+ mice. However, this difference was not as significant as that detected between SHIP-1+/+ and SHIP-1−/− mice. These observations are consistent with the survival analyses data (Figure 2A). Taken together, these results suggest that the progression of erythroleukemia is accelerated in SHIP-1−/− mice compared with SHIP-1+/+ mice.

SHIP-1 knockdown increases phosphorylation of Akt and ERK

To further understand the mechanism by which SHIP-1 is involved in erythroleukemogenesis, SHIP-1 expression was down-regulated using RNA interference (RNAi). A retrovirus expressing either SHIP-1 or negative control nonspecific shRNA and green fluorescence protein was used to infect a SHIP-1–expressing F-MuLV erythroblastic cell line termed HB60-5 (Figure 3A). This unique cell line has previously been shown by our laboratory to have the capacity to undergo terminal erythroid differentiation in response to treatment with Epo.10 Interestingly, ectopic expression of Fli-1 in HB60-5 cells can block Epo-induced differentiation and promote proliferation.10 Transduced HB60-5 cells were sorted twice based on high green fluorescence expression (SHIP-1-shRNA-dbl sort; see “RNA interference”). Double-sorted HB60-5 cells expressing SHIP-1 shRNA displayed a 60% reduction in SHIP-1 expression compared with negative control shRNA-expressing cells (Figure 3A). A clone isolated from this double-sorted cell population, designated SHIP-1 shRNA-8D, displayed an 80% reduction in the levels of SHIP-1. RNAi-mediated down-regulation of SHIP-1 increased the phosphorylation status of Akt and MAPK (Figure 3A), while the expression of another well-known negative regulator of the PI 3-K/Akt pathway, PTEN, remained unchanged (data not shown).

Down-regulation of SHIP-1 in HB60-5 cells blocks differentiation and accelerates proliferation. (A) RNAi-mediated down-regulation of SHIP-1 in HB60-5 double-sorted population (dbl sort) and clone 8D cell populations results in increased Fli-1 expression and increased phosphorylation of AKT and MAPK compared with nonspecific negative control shRNA expressing cells (control). (B) Fli-1 protein expression is reduced in the presence of the PI 3-K inhibitor, LY294002, but not the MAPK inhibitor, PD169316. (C) Northern blot analysis of RNAi-induced SHIP-1 knockdown cells displays reduced Epo-induced differentiation as determined through hybridization with an α-globin probe. Vertical lines have been inserted to indicate a repositioned gel lane. (D) Double-sorted SHIP-1 shRNA expressing HB60-5 cells (SHIP-1 shRNA-11), grown in the presence of Epo, display accelerated proliferation, compared with negative control shRNA-expressing cells. Cells were maintained in 1 U/mL Epo. This experiment was performed in triplicate.

Down-regulation of SHIP-1 in HB60-5 cells blocks differentiation and accelerates proliferation. (A) RNAi-mediated down-regulation of SHIP-1 in HB60-5 double-sorted population (dbl sort) and clone 8D cell populations results in increased Fli-1 expression and increased phosphorylation of AKT and MAPK compared with nonspecific negative control shRNA expressing cells (control). (B) Fli-1 protein expression is reduced in the presence of the PI 3-K inhibitor, LY294002, but not the MAPK inhibitor, PD169316. (C) Northern blot analysis of RNAi-induced SHIP-1 knockdown cells displays reduced Epo-induced differentiation as determined through hybridization with an α-globin probe. Vertical lines have been inserted to indicate a repositioned gel lane. (D) Double-sorted SHIP-1 shRNA expressing HB60-5 cells (SHIP-1 shRNA-11), grown in the presence of Epo, display accelerated proliferation, compared with negative control shRNA-expressing cells. Cells were maintained in 1 U/mL Epo. This experiment was performed in triplicate.

As shown in Figure 3A, down-regulation of SHIP-1 in HB60-5 cells also significantly increased the expression of Fli-1. We hypothesized that the up-regulation of Fli-1 was associated with increased phosphorylation of ERK/MAPK and Akt through the phospholipid created by PI 3-K. To determine whether these signaling pathways were responsible for Fli-1 up-regulation, HB60-5 cells were grown in the presence of PI 3-K (LY294002) and ERK/MAPK (PD169316) inhibitors. As shown in Figure 3B, only the PI 3-K inhibitor was able to reduce Fli-1 expression, suggesting that the effects observed on Fli-1 expression are downstream the PI 3-K pathway.

Our group has previously shown that Fli-1 overexpression blocks Epo-induced erythroid differentiation in HB60-5 cells.10 Therefore, we examined whether SHIP-1 down-regulation is also associated with inhibition of erythroid maturation. SHIP-1-shRNA-dbl sort, SHIP-1-shRNA-8D and control shRNA expressing HB60-5 cells were grown in the presence of 1 U/mL Epo for 72 hours (Figure 3C). SHIP-1 shRNA-dbl sort and SHIP-1-shRNA-8D cells displayed a reduction in α-globin expression, or inhibition of differentiation, in comparison to HB60-5 cells expressing the negative control shRNA. Because Fli-1 overexpression in HB60-5 cells blocks differentiation and promotes proliferation in response to Epo,10 we also examined the proliferation of SHIP-1 down-regulated HB60-5 cells in response to this hormone. HB60-5 cells stably expressing SHIP-1 or negative control shRNAs were grown in the presence of Epo to induce terminal differentiation (1 U/mL). While the proliferation of HB60-5 cells expressing negative control shRNA was negligible in response to Epo, a higher proliferation rate was observed in SHIP-1 dbl sort HB60-5 cells (Figure 3D). Therefore, down-regulation of SHIP-1 was able to alter the Epo-responsiveness of HB60-5 cells from that of maturation to self-renewal and proliferation.

Fli-1 binds to the promoter of SHIP-1

The tightly coupled negative relationship observed between SHIP-1 and Fli-1 suggested that SHIP-1 might be directly down-regulated by Fli-1. To determine whether SHIP-1 is under the transcriptional control of the Fli-1 Ets transcription factor, the mouse promoter region was examined for Ets consensus ACCGGAAG/aT/c DNA-binding sites.31 Upon examination of 1000 bp adjacent to the transcriptional start site of the mouse SHIP-1 promoter, 3 possible Ets DNA binding sites were located, termed EBS1-3 (Figure 4A). Sequence analysis demonstrated a greater than 90% homology between the mouse, human, and rat SHIP-1 promoters in the nucleotides bounded by EBS1 and EBS2 (Figure 4B). Furthermore, the 100% conservation of nucleotide sequences EBS1 and EBS2 in all 3 species implies their significance in the regulation of SHIP-1.

In vitro binding of Fli-1 to the SHIP-1 promoter. (A) The 988-bp promoter region before the start codon of murine SHIP-1 was cloned into the pGL3-enhancer vector. Three possible Ets binding sites (EBS) are highlighted. S1 and S2 indicate the locations of the primers used to amplify the 294-bp region of the SHIP-1 promoter. (B) The SHIP-1 promoter regions of human, mouse, and rat were compared for conservation of nucleotides using BLAST (National Center for Biotechnology Information). The underlined regions (EBS1 and EBS2) are fully conserved in all 3 species. (C) Binding of Fli-1 to the promoters of SHIP-1 (lane 4) and MDM2 (lane 1) as determined by ChIP in CB3, HB60-5, and KH16 erythroleukemic cells using either 2 μg Fli-1 or control rabbit IgG antibody. The MDM2 promoter was used as a positive control, because it is a known Fli-1 target gene.27 (D) ChIP quantitative-PCR in CB3 cells using Fli-1 and normal rabbit IgG antibodies illustrating Fli-1 chromatin occupancy of the indicated gene promoters, as well as a region 3 kb upstream the SHIP-1 promoter (UP-SHIP-1). The β-actin and upstream SHIP-1 promoters were used as negative controls. Results are based on the relative proportions of the input and chromatin precipitated by the Fli-1 and control IgG antibodies, where the input is equal to 1.

In vitro binding of Fli-1 to the SHIP-1 promoter. (A) The 988-bp promoter region before the start codon of murine SHIP-1 was cloned into the pGL3-enhancer vector. Three possible Ets binding sites (EBS) are highlighted. S1 and S2 indicate the locations of the primers used to amplify the 294-bp region of the SHIP-1 promoter. (B) The SHIP-1 promoter regions of human, mouse, and rat were compared for conservation of nucleotides using BLAST (National Center for Biotechnology Information). The underlined regions (EBS1 and EBS2) are fully conserved in all 3 species. (C) Binding of Fli-1 to the promoters of SHIP-1 (lane 4) and MDM2 (lane 1) as determined by ChIP in CB3, HB60-5, and KH16 erythroleukemic cells using either 2 μg Fli-1 or control rabbit IgG antibody. The MDM2 promoter was used as a positive control, because it is a known Fli-1 target gene.27 (D) ChIP quantitative-PCR in CB3 cells using Fli-1 and normal rabbit IgG antibodies illustrating Fli-1 chromatin occupancy of the indicated gene promoters, as well as a region 3 kb upstream the SHIP-1 promoter (UP-SHIP-1). The β-actin and upstream SHIP-1 promoters were used as negative controls. Results are based on the relative proportions of the input and chromatin precipitated by the Fli-1 and control IgG antibodies, where the input is equal to 1.

To confirm the regulation of SHIP-1 by Fli-1, a ChIP experiment was performed with 3 erythroleukemic cell lines (CB3, HB60-5, and KH16) expressing various levels of this Ets transcription factor. While CB3 cells express high levels of Fli-1, HB60-5 cells express lower levels, and KH16 cells lack Fli-1 expression.7,32 Chromatin was isolated and subjected to immunoprecipitation using a Fli-1 antibody.27 The DNA bound to Fli-1 was analyzed by PCR amplifying a 294-bp region within the SHIP-1 promoter using primers S1 and S2 (Figure 4A, lane 4). The results in Figure 4C show that, although no amplification of SHIP-1 promoter is detected in KH16 cells, the levels of Fli-1 product are higher in CB3 cells compared with HB60-5 cells. This result suggests that Fli-1 binds directly to the SHIP-1 promoter, as indicated by the presence of the 294-bp fragment. As expected, this fragment cannot be detected in DNA samples where chromatin was immunoprecipitated using the control nonspecific IgG antibody (Figure 4C lanes 2,5). As a positive control, DNA bound to Fli-1 was PCR amplified in CB3 and HB60-5 cells using primers specific to a region within the promoter of MDM2, a known Fli-1 target gene, generating a 193-bp fragment (Figure 4C, lane 1), as described previously.27 ChIP quantitative PCR was also performed on CB3 cells, using the indicated antibodies, to illustrate Fli-1 chromatin occupancy of the SHIP-1 and MDM2 promoters (Figure 4D). The β-actin promoter, as well as a 3-kb region upstream the SHIP-1 promoter (UP-SHIP-1), were used as negative controls. It is interesting that while SHIP-1 protein expression is undetectable in CB3 cells (Figure 1A-B), ChIP analysis has shown that Fli-1 is capable of binding to the SHIP-1 promoter, indicating an open chromatin structure within the SHIP-1 promoter region of these cells.

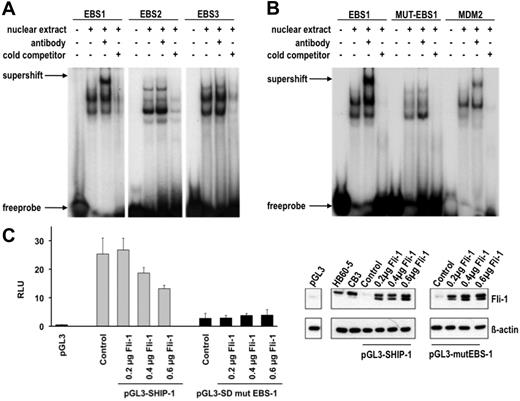

Fli-1 binds to a specific Ets DNA binding sequence and negatively regulates SHIP-1 expression

Because it was established that Fli-1 is capable of binding to the SHIP-1 promoter in vivo, it was logical to determine to which Ets DNA binding site Fli-1 preferentially binds. To determine this, nuclear extracts from erythroleukemic CB3 cells were evaluated by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) for binding radioactively labeled probes corresponding to the putative Ets binding sites. Labeled EBS1-EBS3 oligonucleotides generated multiple bands indicating several probe-protein binding interactions (Figure 5A). However, with the addition of a Fli-1–specific antibody, a supershifted band is observed only with EBS1 (Figure 5A), thereby identifying an EBS1–Fli-1 binding complex. While the other interacting proteins with EBS-1 have not been identified, it is likely that other transcription factors may cooperate with Fli-1 in the regulation of SHIP-1 expression.

Fli-1 binds specifically to EBS1 in the SHIP-1 promoter and negatively regulates its expression. (A) Nuclear extracts from CB3 cells were incubated with EBS1-3 sites in the presence or absence of the Fli-1 antibody and nonspecific competitor poly (dI-dC) and subjected to EMSA. Competition assays were performed in the presence of 10-fold excess unlabeled oligonucleotides (cold competitor). (B) Two nucleotides in EBS1 were changed from ACAGGAAGTCA to ACAGGTTGTCA (designated MUT-EBS-1). Nuclear extracts from CB3 cells were incubated in the presence of poly (dI-dC) and γ-32P-labeled oligonucleotides containing EBS1, MUT-EBS1, or MDM227 and subjected to EMSA and supershifting with the Fli-1 antibody. Competition assays were performed in the presence of 100-fold excess unlabeled oligonucleotides. (C) Luciferase assays were performed in 293T cells cotransfected with the indicated amounts of a Fli-1-expression vector, either the pGL3-SHIP-1 or pGL3-mut-SHIP-1 vector and the Renilla luciferase vector. The pGL3-SHIP-1 luciferase reporter vector contains a 988-bp region within the SHIP-1 promoter (Figure 4A). Site-directed mutagenesis was used to alter nucleotides ACAGGAAGTCA to ACAGGTTGTCA in EBS1 of pGL3-mut-SHIP-1. The relative luciferase units (RLU) are representative of the firefly luciferase/Renilla luciferase signals (×100). Luciferase assays were performed in triplicates. (D) Fli-1 protein expression in 293T cells transfected with the indicated amounts of the Fli-1 expression vector, relative to HB60-5 and CB3 cells. The 2 Fli-1 protein products are observed as a result of 2 isoforms, 48 and 51 kDa, synthesized by alternative translation initiation through the use of 2 highly conserved in-frame initiation codons.47

Fli-1 binds specifically to EBS1 in the SHIP-1 promoter and negatively regulates its expression. (A) Nuclear extracts from CB3 cells were incubated with EBS1-3 sites in the presence or absence of the Fli-1 antibody and nonspecific competitor poly (dI-dC) and subjected to EMSA. Competition assays were performed in the presence of 10-fold excess unlabeled oligonucleotides (cold competitor). (B) Two nucleotides in EBS1 were changed from ACAGGAAGTCA to ACAGGTTGTCA (designated MUT-EBS-1). Nuclear extracts from CB3 cells were incubated in the presence of poly (dI-dC) and γ-32P-labeled oligonucleotides containing EBS1, MUT-EBS1, or MDM227 and subjected to EMSA and supershifting with the Fli-1 antibody. Competition assays were performed in the presence of 100-fold excess unlabeled oligonucleotides. (C) Luciferase assays were performed in 293T cells cotransfected with the indicated amounts of a Fli-1-expression vector, either the pGL3-SHIP-1 or pGL3-mut-SHIP-1 vector and the Renilla luciferase vector. The pGL3-SHIP-1 luciferase reporter vector contains a 988-bp region within the SHIP-1 promoter (Figure 4A). Site-directed mutagenesis was used to alter nucleotides ACAGGAAGTCA to ACAGGTTGTCA in EBS1 of pGL3-mut-SHIP-1. The relative luciferase units (RLU) are representative of the firefly luciferase/Renilla luciferase signals (×100). Luciferase assays were performed in triplicates. (D) Fli-1 protein expression in 293T cells transfected with the indicated amounts of the Fli-1 expression vector, relative to HB60-5 and CB3 cells. The 2 Fli-1 protein products are observed as a result of 2 isoforms, 48 and 51 kDa, synthesized by alternative translation initiation through the use of 2 highly conserved in-frame initiation codons.47

To confirm the specificity of Fli-1 binding to the EBS1 sequence, this binding site was mutated at 2 nucleotides (ACAGGAAGTCA to ACAGGTTGTCA), designated MUT-EBS-1. When the EMSA was repeated using the labeled MUT-EBS1 probe, a Fli-1 supershifted band could not be detected (Figure 5B). A labeled probe corresponding to the known Fli-1 binding site within the MDM2 promoter27 was used as a positive control (Figure 5B). These results demonstrate that Fli-1 regulates SHIP-1 expression through preferential binding to EBS-1.

Fli-1 acts as a repressor and activator of transcription in erythroleukemic cells.10,27,33,34 To ascertain that the identified Fli-1 binding sites are transcriptionally active, a luciferase reporter assay was performed. Position −988 bp from the SHIP-1 transcriptional start site (Figure 4A) was cloned into the pGL3 luciferase reporter vector, termed pGL3-SHIP-1. Cotransfection with the indicated amounts of a Fli-1 expression vector and the pGL3-SHIP-1 vector into 293T cells, lacking both Fli-1 and SHIP-1 expression, resulted in a dose-dependent suppression of luciferase activity (Figure 5C-D). Using the same promoter containing the mutated EBS1 site tested the specificity of Fli-1 binding to the SHIP-1 promoter. This mutation significantly reduced luciferase activity compared with the wild-type pGL3-SHIP-1 construct (Figure 5C), indicating the importance of this site in the regulation of SHIP-1 transcription. In contrast to the wild-type SHIP-1 promoter, Fli-1 expression in 293T cells was unable to cause a dose-dependent suppression of the SHIP-1 mutant luciferase reporter vector (Figure 5C-D). Therefore, Fli-1 suppresses the SHIP-1 promoter by specific binding to EBS-1.

Discussion

The pivotal genetic event in F-MuLV–induced erythroleukemia is the insertional activation at the fli-1 locus, however, despite the initial discovery of fli-1 in the F-MuLV–induced mouse model of leukemogenesis, the mechanism by which this transcription factor transforms erythroblasts remains unclear. The oncogenic effects of Fli-1 overexpression are likely mediated through the regulation of its target genes, and this transcriptional modulation leads to altered cellular signaling events necessary for erythroleukemogenesis. During normal erythroid differentiation, Fli-1 levels are required to be transiently down-regulated in response to Epo stimulation.10 In F-MuLV–induced erythroleukemia, the overexpression of Fli-1 in erythroblasts switches Epo-induced differentiation to Epo-induced proliferation.10,35,36 This response is associated with major changes in Epo signaling, as Fli-1 overexpression induces activation of the Ras pathway resulting in erythroid proliferation.10 In this study, we discovered that the expression of SHIP-1 is negatively regulated by Fli-1 and that the loss of this inositol phosphatase is associated with accelerated leukemogenesis.

Although SHIP-1 protein expression is undetectable in established cell lines, the level of this phosphatase is lower in primary F-MuLV erythroleukemias compared with uninfected controls. Upon examination of the transcriptional regulatory role of Fli-1, it was shown that Fli-1 binds to the SHIP-1 promoter and is transcriptionally suppressed by Fli-1. Similarly, we have previously demonstrated that while the level of p53 in primary erythroleukemias is significantly reduced, the loss of this tumor suppressor gene is detected only in established cell lines.30 Moreover, analogous to SHIP-1−/− mice, F-MuLV–induced erythroleukemia is also accelerated in p53−/− mice.32 The subsequent loss of SHIP-1 in late-stage erythroleukemic cells may provide a selective advantage to allow for EPO-dependent proliferation and immortalization. Therefore, it appears that the loss of SHIP-1 contributes to Fli-1–mediated erythroid transformation, associated with greater activation of the Shc/Ras/MAPK and PI 3-K/Akt pathways.

The suppression of SHIP-1 by Fli-1 has an implication in erythroleukemia progression since SHIP-1 connects the C-terminal region of the Epo-R to the Ras pathway9 and is involved in the regulation of the MAPK and Akt pathways that are downstream the Epo-receptor.37 In support of this data, we have shown that RNAi-mediated knockdown of SHIP-1 in an erythroblastic cell line results in greatly enhanced phosphorylation of MAPK and Akt. Furthermore, these cells displayed a switch from Epo-induced terminal differentiation to Epo-induced proliferation. Because Fli-1 is known to activate or inactivate other genes such as MDM2, bcl-2, gata-1, and rb, all which are known to be mediators of cell proliferation and differentiation,10,27,33,34 the combined regulation of SHIP-1 as well as other target genes may be necessary to confer erythroid transformation.

Activation of the PI 3-K pathway through RNAi-mediated SHIP-1 down-regulation demonstrates the essential role of this signaling pathway in malignant transformation and normal cell function. Indeed, bone marrow-derived mast cells from SHIP-1−/− mice have a prolonged and increased Akt phosphorylation upon IL3-R stimulation.38 Neutrophils isolated from SHIP-1−/− mice stimulated with granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), also exhibit a prolonged and increased phosphorylation of Akt.38 Purified B cells isolated from SHIP-1−/− mice display increased Akt phosphorylation in response to BCR stimulation.11 PI-3,4,5-P3 levels are increased in bone marrow-derived mast cells38 directly triggering the increased activity of Akt. Scheid et al39 have shown that bone marrow-derived mast cells from SHIP-1−/− mice display increased and prolonged Akt phosphorylation in response to stem cell factor (SCF). Furthermore, they found the levels of PI-3,4,5-P3 increased with a substantial reduction of PI-3,4-P2 and no effect on the levels of PI-4,5-P2 in these cells, once more suggesting a direct link between the homozygous deletion of SHIP-1 and increased phosphorylation of Akt.

RNAi-mediated SHIP-1 down-regulation leads to increased phosphorylation of MAPK in comparison to HB60-5 cells expressing the negative control shRNA. Elevated MAPK phosphorylation also occurs in B cells derived from SHIP-1−/− mice in response to BCR-FcγRIIB coligation.11,12 Elevated levels of MAPK and Akt in B cells derived from SHIP-1−/− mice correlate with increased proliferation.11 Moreover, increased Ras activation also leads to PI 3-K activation,40 leading to increased production of PI-3,4,5-P3, thereby contributing to the elevation of phospho-Akt observed in HB60-5 cells subjected to SHIP-1 down-regulation.

Increased MAPK phosphorylation may also be explained by the expression of another SH2 domain-containing protein that binds to the tyrosine residue occupied by SHIP-1 on the Epo-R. Other proteins capable of binding to the Epo-R tyrosine residue 401 (Y401) are STAT5,41 Shp2,11,42 Cis,43,44 and SOCS-3.20,44 Of these proteins, only Shp2 is capable of activating the MAPK pathway, and once Shp-2 is bound to this residue, Grb-2 and SOS can be recruited through Shc.37,42 It is possible that SHIP-1 down-regulation allows Y401 to be available for Shp2 binding, which activates the MAPK pathway more robustly than SHIP-1. Moreover, MAPK phosphorylation in SHIP-1 knockdown cells may also be explained by the presence of the Gab2 scaffolding protein. Gab2 associates with Grb2, Shp2, the p85 subunit of PI 3-K, and most likely indirectly associates with SHIP-1 and Shc.45 In these cells, Gab2 may be binding to Shp2 increasing downstream MAPK phosphorylation. Moreover, Gab2 associates with the p85 subunit of PI 3-K, which could lead to increased activation of the PI 3-K/Akt pathway. Gab2 has been shown to associate with a membrane proximal region of the Epo-R cytoplasmic tail containing Y343 and Y401.46

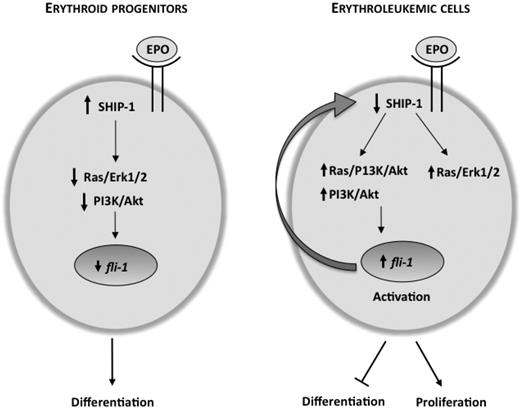

While down-regulation of SHIP-1 activates the MAPK and Akt pathways in HB60-5 cells, it also results in Fli-1 up-regulation. Interestingly, Fli-1 is capable of suppressing SHIP-1 expression through direct interaction to its promoter. This was also apparent by a negative correlation detected in the levels of SHIP-1 and Fli-1 in both cell lines and in primary erythroleukemias. Because SHIP-1 negatively regulates PI 3-K, which is upstream of Fli-1, we propose a negative feedback loop model (Figure 6) in which the balance between the expressions of these genes promotes either cell proliferation or differentiation. When erythroid cells undergo differentiation, Fli-1 down-regulation10 increases SHIP-1 levels leading to decreased phosphorylation of MAPK and Akt or lack of responsiveness to the differentiation stimulus. However during erythroid proliferation, Fli-1 overexpression, occurring as a result of proviral integration, reduces SHIP-1 expression and leads to higher levels of MAPK and Akt and, subsequently, erythroid transformation.9 Therefore, we hypothesize that Fli-1 lies downstream of the PI 3-K/Akt, Ras/PI 3-K/Akt interactions and direct PI 3-K/Akt interactions control the expression of this transcription factor.

Negative feedback loop model of Fli-1 and SHIP-1 regulation. During Epo-induced differentiation of erythroid progenitor cells, SHIP-1 expression is high and is able to negatively regulate the PI 3-K/Akt pathway, leading to lower Fli-1 expression. Upon activation of Fli-1 as a result of insertional mutagenesis, the PI 3-K/Akt and the Ras/MAPK pathways are activated. Increased activity of Akt through the PI 3-K/Akt and/or Ras/PI 3-K/Akt pathways further increases transcription of fli-1, leading to a block in differentiation and acceleration of proliferation by Epo. As Fli-1 levels increase, SHIP-1 transcription is suppressed to a greater extent, eventually resulting in complete repression in late stage erythroleukemia.

Negative feedback loop model of Fli-1 and SHIP-1 regulation. During Epo-induced differentiation of erythroid progenitor cells, SHIP-1 expression is high and is able to negatively regulate the PI 3-K/Akt pathway, leading to lower Fli-1 expression. Upon activation of Fli-1 as a result of insertional mutagenesis, the PI 3-K/Akt and the Ras/MAPK pathways are activated. Increased activity of Akt through the PI 3-K/Akt and/or Ras/PI 3-K/Akt pathways further increases transcription of fli-1, leading to a block in differentiation and acceleration of proliferation by Epo. As Fli-1 levels increase, SHIP-1 transcription is suppressed to a greater extent, eventually resulting in complete repression in late stage erythroleukemia.

The higher number of erythroid progenitors in SHIP-1−/− mice19 is associated with higher levels of Fli-1 expression in the leukemic spleens of these mice. It is plausible that the acceleration of F-MuLV–induced leukemogenesis in these mice is also partially attributed to this increase in the number of erythroid target cells. However, the loss of SHIP-1 alone is not sufficient to render the erythroid progenitors tumorigenic. The increased proliferation of normal and transformed erythroblasts in SHIP-1−/− mice, responsible for the increased proportion of erythroid progenitors, suggests that both elevated numbers of erythroid progenitor target cells and their increased proliferation rate may cooperate to confer accelerated leukemogenesis in SHIP-1−/− mice. Moreover, cooperation between these factors as well as activation or inactivation of other Fli-1 target genes may be critical to confer erythroid transformation in F-MuLV–infected mice. Therefore the loss of SHIP-1 plays an important role, although not an essential one, in F-MuLV–induced erythroleukemogenesis.

In summary, we have demonstrated that Fli-1 is able to target and suppress the transcription of SHIP-1 through binding to a specific and unique Fli-1 Ets consensus DNA-binding sequence within the SHIP-1 promoter. Therefore SHIP-1 can be added to a growing list of genes targeted by Fli-1 during erythropoiesis and leukemogenesis. Furthermore, a negative feedback loop existing between SHIP-1 and Fli-1 is able to alter Epo signaling and lead to either erythroid proliferation or differentiation. In this study, we have demonstrated, for the first time that Fli-1 is downstream of the SHIP-1/PI 3-K/Akt pathway that plays an important role during Fli-1–mediated erythroid transformation.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms Melanie Suttar for her excellent secretarial assistance.

This work was supported by a grant from the Terry Fox Foundation through the National Cancer Institute of Canada (NCIC) and the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR) to Y.B.D. (MOP84460) and D.L.B. (13 612), the Cancer Research Society Inc. to D.L.B., and the National Science Fund for Young Scholars (30901702) to J.-W.C.

Authorship

Contribution: G.K.L. designed and performed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; L.M.V.-F. designed and performed the experiments in Figures 1B,D and 4A,D, designed the RNAi experiments in Figure 3, provided constructive input, and wrote and edited the manuscript; Y.-J.L. designed the research, analyzed the data, and performed the experiments presented in Figures 1A, 3C, and 4C; J.-W.C. designed performed the experiment in Figure 5C. M.L.B. aided in the analysis of SHIP-1–deficient mice, and assisted G.K.L. in experiments described in Figure 2D; D.E.S. provided constructive input on the outcome of this project; D.E.S. and D.J.D. provided constructive input on the outcome of this project and reviewed the manuscript; D.L.B. provided us with SHIP-1 knockout mice, assisted G.K.L. in analyzing experiments, and reviewed the manuscript; and Y.B.D. is the principal investigator, who was involved in designing the experiments and analyzing the overall data presented in this study.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Yaacov Ben-David, Department of Medical Biophysics, University of Toronto, Molecular and Cellular Biology, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, 2075 Bayview Ave, Toronto, ON, M4N 3M5 Canada; e-mail: bendavid@sri.utoronto.ca.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal