Abstract

Abstract 2951

The identification of stereotyped immunoglobulin (IG) receptors has improved our knowledge on the pathogenesis of several B-cell malignancies, suggesting the role of antigen-driven stimulation in chronic lymphocitic leukemia (CLL), marginal-zone lymphoma (MZL) and mantle-cell lymphoma (MCL). Multiple myeloma (MM) is a terminally-differentiated neoplasm no longer expressing surface IG; however some reports suggest the existence of early B-lymphocyte precursors which could be susceptible to antigen-driven stimulation. IG heavy chain (IGH) repertoire has not been extensively investigated in MM, with the largest available reports containing less than 80 complete sequences.

To address this issue we created a database of MM IGH sequences including our institutional records (mostly derived from minimal residual disease studies) and sequences available from the literature. We planned a two-step analysis: a) first we characterized the MM repertoire and performed intra-MM clustering analysis; b) then we compared our MM series to a large public database of IGH sequences from neoplastic and non-neoplastic B-cells in search of similarities between MM sequences and other normal or neoplastic IGH repertoires.

131 MM IGH genes were amplified and sequenced at our Institutions and belonged to Italian patients, while 214 MM IGH sequences from non-Italian patients were derived from published databases (NCBI-EMBL-IMGT/LIGM-DB) for a total of 345 fully interpretable MM sequences (out of 396). 28590 IGH sequences from other malignant and non-malignant B-cells were retrieved from the same public databases, including approximately 4500 CLL/Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) sequences and comprising 500 sequences from Italian patients. All sequences were analyzed using the IMGT database and tools (Lefranc et al., Nucleic Acid Res. 2005; http://imgt.cines.fr/) to identify IGHV-D-J gene usage, to assess the somatic hypermutation (SHM) rate and to identify HCDR3. HCDR3 aminoacidic sequences were aligned together using the ClustalX 2.0 software (Larkin et al., Bioinformatics, 2007; http://www.clustal.org/). Subsets of stereotyped IGH receptors were defined according to Stamatopoulos et al. (Blood, 2007).

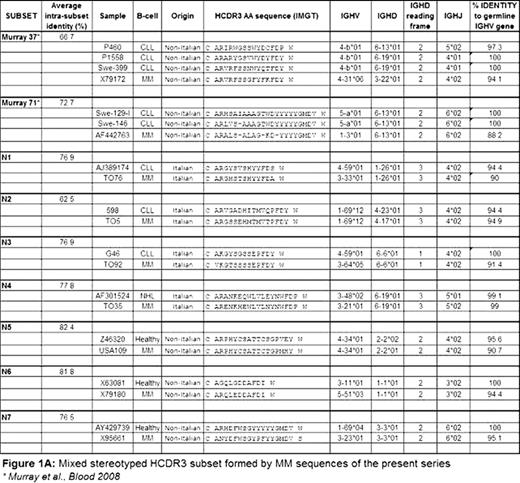

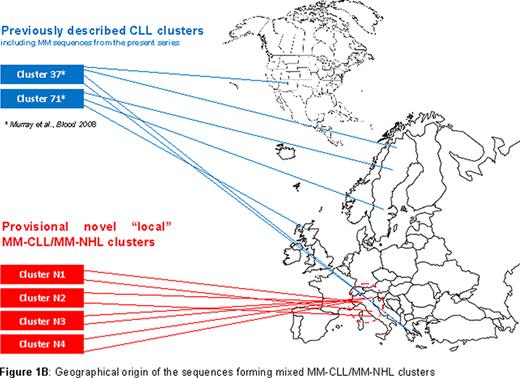

IGHV analysis in MM was almost in keeping with the normal B-cell repertoire, showing a less remarkably biased IGH usage compared to CLL, MCL and MZL (with seven genes accounting for 40% of cases, compared to respectively five, three and two genes). However, a modest but significant over-representation of IGHV1-69, 2–5, 2–70, 3–21, 3–30-3, 3–43, 5–51 and 6-1 genes and under-representation of the IGHV1-18, 1–8, 3–30, 3–53 and 4–34 was noticed. The rate of somatic hypermutation in MM followed a Gaussian distribution with a median value of 7.8%. Intra-MM search for HCDR3 similarities never met minimal requirements for stereotyped receptors. When MM sequences were compared to non-MM database, only a minority of MM sequences (2.6%, n=9) clustered with sequences from lymphoid tumors and normal B-cells (figure 1A). In particular two non-Italian MM sequences clustered with previously characterized, uncommon CLL subsets (n.37 and n.71 according to Murray et al., Blood 2008). Moreover, novel provisional clusters were observed including three MM-CLL subsets, one MM-NHL subset, and three MM-normal B-cell subsets. While the MM-normal B-cell clusters involved non-Italian patients, we unexpectedly noticed that the four MM-CLL/MM-NHL clusters were composed exclusively of Italian patients, as shown in figure 1B, although Italian subjects represented less than 12% of the entire CLL-NHL database.

The analysis of the largest currently available database of MM IGH sequences indicates the following: 1) MM IGH repertoire is closer to physiological distribution than that of CLL, MCL and MZL; 2) MM specific clusters do not occur to a frequency detectable with currently available databases; 3) 98% of MM sequences are not related to other “highly-clustered” lymphoproliferative disorders; 4) Uncommon clustering phenomena may follow a geographical rather than a disease-related pattern.

No relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal