Abstract

Infants infected with HIV have a more severe course of disease and persistently higher viral loads than HIV-infected adults. However, the underlying pathogenesis of this exacerbation remains obscure. Here we compared the rate of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell proliferation in intestinal and systemic lymphoid tissues of neonatal and adult rhesus macaques, and of normal and age-matched simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)–infected neonates. The results demonstrate infant primates have much greater rates of CD4+ T-cell proliferation than adult macaques, and that these proliferating, recently “activated” CD4+ T cells are infected in intestinal and other lymphoid tissues of neonates, resulting in selective depletion of proliferating CD4+ T cells in acute infection. This depletion is accompanied by a marked increase in CD8+ T-cell activation and production, particularly in the intestinal tract. The data indicate intestinal CD4+ T cells of infant primates have a markedly accelerated rate of proliferation and maturation resulting in more rapid and sustained production of optimal target cells (activated memory CD4+ T cells), which may explain the sustained “peak” viremia characteristic of pediatric HIV infection. Eventual failure of CD4+ T-cell turnover in intestinal tissues may indicate a poorer prognosis for HIV-infected infants.

Introduction

Rapid and profound loss of “activated” memory CD4+ T cells, particularly in the intestine, is a hallmark of both HIV and simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infection. However, the mechanism by which CD4+ T cells are eliminated in early infection remains obscure. Furthermore, infants usually have a more rapid and severe course of disease, with persistently higher viral loads than adults with HIV infection.1-5 Because neonates are believed to be born with mostly “naive” T cells, why would HIV infection be more severe in infants, who have far fewer of the “activated” memory CD4+ T cells required to fuel viral replication?

It is well established that the intestinal tract is a major site of early HIV/SIV infection in adults6-10 and prior studies in SIV-infected neonates showed that as in adults, intestinal CD4+ T cells are also the major target for early pediatric SIV infection.11,12 Furthermore, most intestinal CD4+ T cells in the intestinal lamina propria of normal neonatal macaques already have an “activated, memory” phenotype, even on the day of birth, despite not having encountered environmental antigens outside the womb.11 This suggests that neonates have ample target cells to support HIV infection and amplification, even prior to birth, and that these intestinal cells may be capable of mounting functional immune responses. However, absolute numbers and percentages of these target cells are far fewer in neonates than adults, so this alone cannot explain the higher viral loads in infected neonates. Because neonates are immediately exposed to a variety of new environmental antigens after birth, we hypothesized that increased activation, infection, and perhaps most importantly, a more sustained turnover of viral target cells in neonatal intestines could potentially explain why neonates have sustained viral loads and accelerated disease progression.

To date, information on T-cell turnover rates is limited to peripheral blood, and few studies have examined proliferation and T-cell turnover in tissues, particularly the intestinal tract, the primary target for acute SIV and HIV infection. Furthermore, little data on mucosal immune responses to HIV or SIV infection of neonates have been published. To monitor proliferation of cell subsets in tissues, we administered bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) to neonates 24 hours prior to tissue collection. Because BrdU is a thymidine analog incorporated only by cells synthesizing DNA, this method allows for detection of cells in the synthesis phase (S-phase) of cell division. Proliferation rates of T-cell subsets were compared in the blood, lymph nodes, spleen, and intestines of adult and pediatric macaques, as well as pediatric macaques infected with SIVmac251 and age-matched uninfected controls.

Methods

Animals, virus, and BrdU inoculation

Tissues from 23 infected and 20 age-matched uninfected neonatal rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) were obtained from the Tulane National Primate Research Center. All monkeys were housed and maintained in accordance with the standards of the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care, and all studies were reviewed and approved by the Tulane Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All neonatal macaques were obtained at birth and hand reared on formula thereafter. Tissues from 10 uninfected adult macaques (4-12 years old) were also examined for comparison. Experimental animals were intravenously infected with 100 TCID50 SIVmac251 within 24 hours of birth, and humanely euthanized at 3 (n = 3), 7 (n = 3), 10-14 (n = 5), 21 (n = 4), or over 48 days after infection (n = 8) for comparison with age-matched uninfected controls. For in vivo BrdU pulse labeling, BrdU (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in saline (20 mg/mL), filter-sterilized, and intra-peritoneally inoculated into macaques (60 mg/kg) 24 hours prior to tissue collection.

Tissue collection and analysis

Whole blood and spleen samples were stained using a whole blood lysis protocol as previously described.11 Intestinal lamina propria and lymph node cell suspensions were prepared as previously described.11 Cell suspensions were adjusted to 107 cells-mL and 100-μL aliquots (106 cells) were stained for 30 minutes at 4°C with appropriately diluted concentrations of monoclonal antibodies against CCR5-phycoerythrin (PE), CD8-peridinin-chlorophyll-protein complex, CD4-allophycocyanin (APC), CD95-PE-Cy5, HLADR-PE-Cy7, CD28-APC or CD20-APC, CD69-APC-Cy7, CD3-Pacific Blue (BD Biosciences), CD8-PE-TR (Caltag Laboratories), and CD4-Qdot655 (National Institutes of Health; NIH) for 4 to 12 color flow cytometry. For intracellular staining, surface stained cells were washed in Dulbecco phosphate-buffered saline/bovine serum albumin, fixed, and permeabilized with BD Cytofix/Cytoperm buffer (BD Biosciences) followed by staining for BrdU, according to the manufacturers' instructions, including a 1-hour incubation with DNAase followed by washing with BD Perm/Wash buffer and staining with fluorescent anti-BrdU for 20 minutes at room temperature. Cells were washed again (BD Perm/Wash buffer) and all samples were resuspended with BD Stabilizing Fixative buffer (BD Biosciences) and acquired on a fluorescence-activated cell sorting Calibur (4-color samples) or a fluorescence-activated cell sorting Aria flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson) for 10 color samples within 24 hours of fixation. Data were analyzed with FlowJo software Version 6.4.7 (Tree-Star). At least 10 000 lymphocytes were collected for analysis from each sample, and data were analyzed by gating through lymphocytes and then through cells of interest as described.

Phenotyping SIV-infected cells in tissues by in situ hybridizaton and multilabel confocal microscopy

Infected cells were identified in tissues in situ by multilabel confocal microscopy. A combination of 3-color immunofluorescence for CD3 and BrdU and in situ hybridization for SIVmRNA was performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections of selected animals. Briefly, 5-μm sections were cut and adhered to charged glass slides. After deparaffinization in xylene, rehydration in phosphate-buffered saline, and antigen retrieval with steam (citrate buffer), sections were incubated with anti-sense SIV riboprobes (Lofstrand Labs Ltd) encompassing essentially the entire SIV genome as previously described.13 SIVmRNA+ cells were detected by the 2-hydroxy-3-napthoic acid-2 phenylanalide phosphate (HNPP) Fluorescent Detection Set (Roche Diagnostics Corporation; red). Furthermore, SIV-infected cells detected by this technique were also colabeled using unconjugated primary antibodies for BrdU and CD3 (both from DakoCytomation), and then with secondary antibodies conjugated to either Alexa 488 or Alexa 633 (Molecular Probes). After staining, slides were washed, mounted with fluorescent mounting medium (DakoCytomation) and visualized using a confocal microscope. Confocal microscopy was perfomed using a Leica TCS SP2 confocal microscope equipped with 3 lasers (Leica Microsystems). Individual optical slices representing 0.2 μm, and 32 to 62 optical slices were collected at 512 × 512 pixel resolution. NIH Image (Version 1.62) and Adobe Photoshop (Version 7.0; Adobe Systems) were used to assign colors to the channels collected: HNPP/Fast Red, which fluoresces when exposed to a 568-nm wavelength laser, appears red; Alexa 488 (Molecular Probes) appears green; Alexa 633 (Molecular Probes) appears blue; and the differential interference contrast (DIC) image is gray scale. The 4 channels were collected simultaneously.

To determine the proportion of proliferating cells infected with SIV, lymph nodes, spleen, and intestine from macaques in primary infection (day 7) were sectioned and triple labeled as in the previous paragraph for SIV, CD3 and BrdU, and the total number of SIV-infected T cells (SIV+CD3+) and proliferating SIV-infected T cells (BrdU+SIV+CD3+) were counted and the proportion of proliferating infected T cells calculated.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with a Mann Whitney U test using GraphPad Prism software (Version 5.0c). P values < .05 were considered significant.

Results

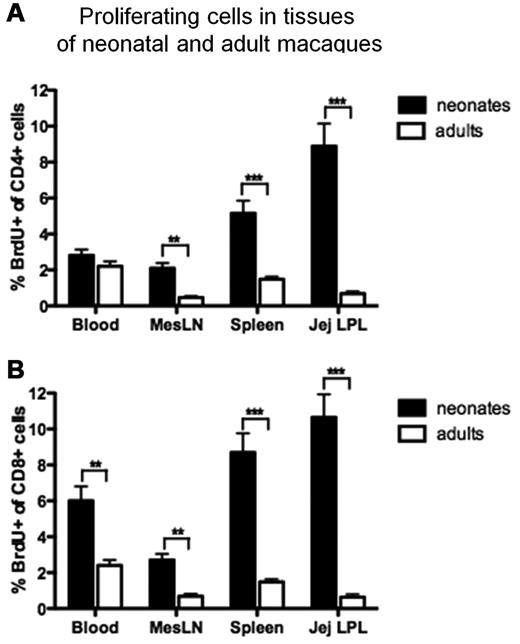

Neonates have more proliferating T cells in tissues than adults

In all tissues examined, percentages of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in S-phase division (BrdU+) were markedly higher in neonates compared with adults (Figure 1). In fact, the only subset that did not show significantly higher rates of proliferation in neonates were CD4+ T cells in blood (Figure 1A). Importantly however, there were 10-fold higher levels of BrdU+ T cells (both CD4+ and CD8+) in the jejunum, and at least 4-fold higher levels in spleen of neonatal macaques compared with same tissues from adults (Figure 1).

Comparison of proliferating (BrdU+) CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells from various tissues of uninfected adults and neonatal rhesus macaques. (A) CD4+ T cells. (B) CD8+ T cells. Black bars represent means of 13 normal neonatal macaques (3-21 days old), and white bars represents 10 normal adult macaques (> 4 years old). Note that neonates have far more proliferating T cells than adults, especially in the intestine and spleen. Bars represent mean percentages of BrdU+ lymphocytes gated through CD4 and/or CD8 ± SEM. Significant differences between adults and neonates are indicated by asterisks (**P < .01, ***P < .001) using a Mann Whitney U test.

Comparison of proliferating (BrdU+) CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells from various tissues of uninfected adults and neonatal rhesus macaques. (A) CD4+ T cells. (B) CD8+ T cells. Black bars represent means of 13 normal neonatal macaques (3-21 days old), and white bars represents 10 normal adult macaques (> 4 years old). Note that neonates have far more proliferating T cells than adults, especially in the intestine and spleen. Bars represent mean percentages of BrdU+ lymphocytes gated through CD4 and/or CD8 ± SEM. Significant differences between adults and neonates are indicated by asterisks (**P < .01, ***P < .001) using a Mann Whitney U test.

To phenotype proliferating cells, we examined the coexpression of CD95 (a memory marker) and CD69 (early activation marker) on BrdU+, CD4+, and CD8+ T-cell subsets (Figure 2). Significant differences in levels of coexpression of CD95 and BrdU+ cells on CD4 and CD8+ T cells were detected between tissues, especially in 3-day-old neonates. Almost all (mean 88% [range 81%-95%]) of the proliferating (BrdU+) CD4+ T cells in the intestine coexpressed CD95, yet only half or fewer of blood (56%), spleen (51%), or mesenteric lymph node (23%-45%) CD4+ T cells had a memory phenotype (Figure 2A). In addition, a lower percentage of proliferating CD8+ T cells had a memory phenotype compared with CD4+BrdU+ T cells (Figure 2A,C). However, levels of CD95 increased on both CD4+BrdU and CD8+BrdU+ T cells with age in the latter tissues (Figure 2A). Combined, these data suggest that the proliferating cells (especially CD4+ T cells) in the intestine were in a more advanced stage of differentiation compared with those in peripheral tissues.

Phenotype of proliferating (BrdU+) CD4 and CD8 T cells in various tissues of normal neonatal macaques. Memory cells are defined as CD95+ (A,C), and activated cells as CD69+ (B,D). Data are expressed as means ± SE. Note that the majority of the proliferating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the intestine have a memory phenotype (CD95+) whereas fewer memory cells are proliferating in other tissues in early development. Note approximately 90% of the proliferating CD4+ T cells in the jejunum of 3-day-old infants are have whereas only approximately 55% are proliferating in blood through the first 14 days of development (A). Fewer proliferating T cells have a memory phenotype in lymph nodes and spleen, yet these rapidly increase with age. In addition, most of the proliferating T cells in the intestine are “activated” (CD69+), whereas proliferating T cells rarely coexpress CD69+ in the spleen, and none in blood. Interestingly, the spleen has higher levels of activated, proliferating cells than blood or lymph node, but still fewer than the intestine.

Phenotype of proliferating (BrdU+) CD4 and CD8 T cells in various tissues of normal neonatal macaques. Memory cells are defined as CD95+ (A,C), and activated cells as CD69+ (B,D). Data are expressed as means ± SE. Note that the majority of the proliferating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the intestine have a memory phenotype (CD95+) whereas fewer memory cells are proliferating in other tissues in early development. Note approximately 90% of the proliferating CD4+ T cells in the jejunum of 3-day-old infants are have whereas only approximately 55% are proliferating in blood through the first 14 days of development (A). Fewer proliferating T cells have a memory phenotype in lymph nodes and spleen, yet these rapidly increase with age. In addition, most of the proliferating T cells in the intestine are “activated” (CD69+), whereas proliferating T cells rarely coexpress CD69+ in the spleen, and none in blood. Interestingly, the spleen has higher levels of activated, proliferating cells than blood or lymph node, but still fewer than the intestine.

Examining CD69 expression on proliferating cells also showed that a much higher percentage of intestinal CD4+BrdU+ T cells had an activated phenotype in uninfected neonates. As shown in Figure 2B, between 42% and 69% of the proliferating CD4+ T cells coexpressed CD69 in the jejunum of 3 day old macaques, whereas, only 8%-15% of spleen, and 15%-23% of lymph node BrdU+CD4+ T cells coexpressed CD69. In blood, CD69 expression was essentially absent on CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes. CD8+ T cells showed similar patterns of activation and memory status in the tissues examined (Figure 2C-D). Interestingly, proliferating cells in the blood lacked CD69 expression in all uninfected neonates examined, which is consistent with previous reports that circulating neonatal T cells are essentially all naive or “resting” cells, although some were clearly dividing. Combined, the data show proliferating intestinal CD4+ T cells have an activated, memory phenotype, yet most T cells in peripheral lymphoid tissues have a naive, resting phenotype, suggesting that different mechanisms of T-cell proliferation and homeostasis may exist in different tissues of neonatal primates.

Plasma viremia in SIVmac251 infected neonatal macaques

Peak viral loads of 107 to 108 RNA copies/mL were attained in plasma between 7 and 14 days of infection, with most peaking by day 7 (Figure 3). In contrast to SIV-infected adults who demonstrate a clear peak and then decline to a viral “set point,” the neonates sustained high viral loads with little difference between “peak” and “set point” viremia, which has also been observed in pediatric AIDS patients.14-16

Mean plasma viral loads in neonatal macaques infected with SIVmac251 as determined by bDNA assay. Note that viral loads do not “peak,” and instead remain persistently elevated in pediatric macaques throughout the course of infection. Error bars reflect SEM. The limit of detection was 125 viral copies/mL plasma.

Mean plasma viral loads in neonatal macaques infected with SIVmac251 as determined by bDNA assay. Note that viral loads do not “peak,” and instead remain persistently elevated in pediatric macaques throughout the course of infection. Error bars reflect SEM. The limit of detection was 125 viral copies/mL plasma.

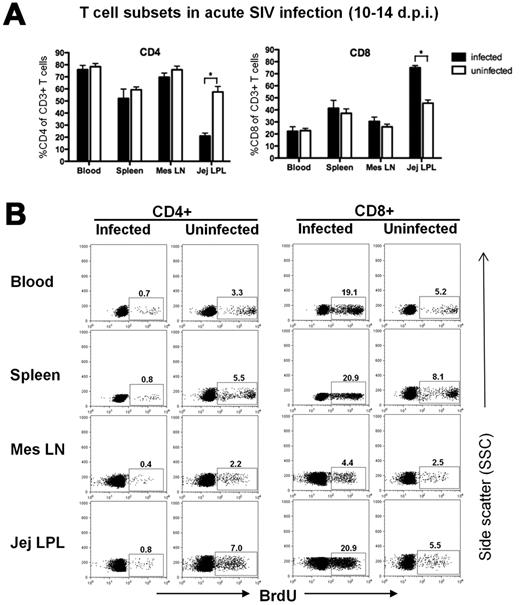

Rapid, profound, and selective depletion of proliferating CD4+ T cells occurs in SIV-infected neonates

We previously reported that CD4+ T cells were markedly depleted in the intestine of neonates within 10 to 14 days of SIV infection, yet CD4 cells in the blood and lymph nodes were essentially unchanged.11,12 The data in Figure 4A recapitulate this prior data and also show a reciprocal increase in CD8+ T cells in the jejunum within 14 days of infection. To examine changes in proliferating subsets of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in these tissues during primary infection of neonatal macaques, we compared percentages of BrdU+ T-cell subsets in neonates with age-matched uninfected controls. In SIV-infected neonates, we found a rapid and dramatic loss of proliferating CD4+ T cells in all tissues examined, and essentially a selective depletion of these cells in the intestine (Figures 4–5). The converse was observed when examining BrdU+ CD8+ T cells, as dramatically increased levels of proliferating CD8 T cells were detected in SIV-infected neonates by 10 to 14 days postinfection (dpi; Figures 4–5). Although the loss of proliferating CD4+ T cells significantly differed from controls by 10 to 14 days after SIV infection, decreased (but not significantly) levels of BrdU+CD4+ T cells persisted in macaques infected for 21 days and longer, suggesting ongoing loss with attempted compensatory recovery of CD4+ T cells in chronic infection. Levels were also lower in macaques with AIDS than either chronically infected animals or controls, suggesting that failure to maintain a threshold of these crucial cells correlates with a grave prognosis (Figure 5). There was also a massive and selective loss of BrdU+ CD4+ T cells in all tissues examined by 14 dpi comparing individual age-matched controls to infected neonates (Figure 5). In contrast, BrdU+ CD8+ T cells were markedly increased in SIV-infected neonates at this timepoint compared with age-matched controls, indicating a successful proliferative response to infection (Figure 5). Interestingly, although we found marked increases in proliferating CD8+ T cells in SIV-infected neonates by 10-14 dpi, levels did not remain significantly elevated over those of uninfected controls by 21 dpi, and thereafter (Figure 5).

Examination of total CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and percentages of proliferating T-cell subsets from various tissues of neonates 10-14 days after SIV infection. (A) Bar charts demonstrating marked depletion of intestinal CD4+ T cells occurs by 10-14 dpi, accompanied by significant increases in intestinal CD8+ T cells, yet minimal changes are detected in CD4+/CD8+ T cells in the blood, lymph node or spleen in early SIV infection. Bars represent percentage of CD3+ gated lymphocytes expressing CD4 or CD8. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (B) Representative flow cytometry confirms marked and selective depletion of proliferating (BrdU+) CD4+ T cells (left panels) concurrent with marked increase in CD8+ T-cell proliferation in early SIV infection (right panels). All plots were generated by gating through CD3+ lymphocytes and then CD4+ or CD8+ T cells. Data in panel B are from representative plots from a SIV-infected neonate 12 dpi and an age-matched (12-day-old) uninfected control.

Examination of total CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and percentages of proliferating T-cell subsets from various tissues of neonates 10-14 days after SIV infection. (A) Bar charts demonstrating marked depletion of intestinal CD4+ T cells occurs by 10-14 dpi, accompanied by significant increases in intestinal CD8+ T cells, yet minimal changes are detected in CD4+/CD8+ T cells in the blood, lymph node or spleen in early SIV infection. Bars represent percentage of CD3+ gated lymphocytes expressing CD4 or CD8. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (B) Representative flow cytometry confirms marked and selective depletion of proliferating (BrdU+) CD4+ T cells (left panels) concurrent with marked increase in CD8+ T-cell proliferation in early SIV infection (right panels). All plots were generated by gating through CD3+ lymphocytes and then CD4+ or CD8+ T cells. Data in panel B are from representative plots from a SIV-infected neonate 12 dpi and an age-matched (12-day-old) uninfected control.

Changes in proliferating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in neonatal tissues in SIV infection. Bars reflect percentages of each subset labeled with BrdU in respective tissues of SIV-infected (black bars) and uninfected age-matched normal neonates (white bars) at various stages of acute infection or age. Note by 12-14 dpi, there is marked depletion of proliferating CD4+ T cells (left) corresponding with a significant increase in proliferating CD8+ T cells (right). Data represent mean percentages of BrdU+ cells gated through either CD4+ or CD8+ T cells in each group ± SEM).

Changes in proliferating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in neonatal tissues in SIV infection. Bars reflect percentages of each subset labeled with BrdU in respective tissues of SIV-infected (black bars) and uninfected age-matched normal neonates (white bars) at various stages of acute infection or age. Note by 12-14 dpi, there is marked depletion of proliferating CD4+ T cells (left) corresponding with a significant increase in proliferating CD8+ T cells (right). Data represent mean percentages of BrdU+ cells gated through either CD4+ or CD8+ T cells in each group ± SEM).

As shown in Figure 6A, very early depletion of proliferating memory CD4+ T cells was first detectable in the intestine of neonates by 3 to 7 days of SIV infection. Moreover, marked depletion of proliferating memory CD4+ T cells persisted in all tissues examined in infected neonates, especially those that rapidly progressed to AIDS (Figure 6B) suggesting that failure to replenish these cells correlates with disease progression. Combined, these results suggest that rapid, profound, and persistent, ongoing loss of proliferating memory CD4+T cells occurs in all tissues of SIV-infected neonates, but this depletion is most pronounced in the gut. Furthermore, the fact that the loss of proliferating CD4+ T cells is detectable by 7 days of infection suggests that this may be due to direct viral infection and destruction of cells rather than an effect of chronic immune activation. To address this, we phenotyped SIV-infected cells in tissues in situ by confocal microscopy.

Changes in proliferating memory CD4+ T-cell subsets in neonatal tissues in pediatric SIV infection. (A) Very early, selective depletion of proliferating memory (BrdU+ CD95+) CD4+ T cells was consistently observed in the intestine of infected neonates by 3-7 days of infection. (B) After 21 days infection, massive loss of proliferating memory CD4+ T cells persists in all tissues examined. Flow cytometric plots indicate the distribution and frequency of proliferating (BrdU+, blue) cells in tissues having an activated (CD69+) and/or memory (CD95+) phenotype among all gated CD4+ T lymphocytes. Plots were gated through CD3+CD4+ lymphocytes. Data are expressed as means ± SE (*P < .05, **P < .01).

Changes in proliferating memory CD4+ T-cell subsets in neonatal tissues in pediatric SIV infection. (A) Very early, selective depletion of proliferating memory (BrdU+ CD95+) CD4+ T cells was consistently observed in the intestine of infected neonates by 3-7 days of infection. (B) After 21 days infection, massive loss of proliferating memory CD4+ T cells persists in all tissues examined. Flow cytometric plots indicate the distribution and frequency of proliferating (BrdU+, blue) cells in tissues having an activated (CD69+) and/or memory (CD95+) phenotype among all gated CD4+ T lymphocytes. Plots were gated through CD3+CD4+ lymphocytes. Data are expressed as means ± SE (*P < .05, **P < .01).

Proliferating CD4+ T cells are selectively infected with SIV in vivo

Multilabel confocal microscopy for SIV, BrdU, and CD3 revealed that large numbers of SIV-infected T cells were BrdU+/proliferating cells, particularly in very early infection (prior to the CD4 depletion). Note that within 7 days of infection, large numbers of BrdU+ cells are infected with SIV in this representative macaque (Figure 7). In fact, SIV+BrdU+CD3+ T cells were frequently detected in all tissues examined (such as spleen and mesenteric lymph nodes) of macaques just prior to the massive depletion of BrdU+CD4+ T cells (Figure 7A-D). To determine relative percentages of infected proliferating cells in SIV-infected T cells in tissues, representative sections of mesenteric lymph node, spleen, and intestine from animals in early infection were triple labeled for SIV, CD3, and BrdU, and the proportion of proliferating (BrdU+) SIV-infected T cells (BrdU+ SIV+ CD3+) was determined for each tissue. We found an average of 55.7% (range, 37%-71%), and 60% (range 30%-80%) of the total SIV-infected cells were BrdU positive in lymph nodes and spleen, respectively. Surprisingly, the rate was even higher in the intestine as a mean of 70% of SIV-infected cells in the intestine were proliferating (BrdU+).

Phenotyping SIV-infected T cells in tissues by combined immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization for SIV RNA. As indicated by arrows, SIV-infected cells (SIV mRNA, red) are all CD3+ T cells (CD3+, blue). Also note large percentages of the infected cells (deep red) in all tissues examined are proliferating (BrdU+, green) which appear as either red/green or yellow/white (arrows). (A) mesenteric lymph node; (B) spleen; (C-D) intestinal organized lymphoid tissue and lamina propria, respectively. This is easier appreciated in the overlapping individual panels on the left. Also note “fuschia” colored cells in panels B and D are red blood cells that are an artifact of certain immunohistochemical techniques, and should not be interpreted as infected cells. Representative “fuschia” cells are as shown within circles in panels B and D.

Phenotyping SIV-infected T cells in tissues by combined immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization for SIV RNA. As indicated by arrows, SIV-infected cells (SIV mRNA, red) are all CD3+ T cells (CD3+, blue). Also note large percentages of the infected cells (deep red) in all tissues examined are proliferating (BrdU+, green) which appear as either red/green or yellow/white (arrows). (A) mesenteric lymph node; (B) spleen; (C-D) intestinal organized lymphoid tissue and lamina propria, respectively. This is easier appreciated in the overlapping individual panels on the left. Also note “fuschia” colored cells in panels B and D are red blood cells that are an artifact of certain immunohistochemical techniques, and should not be interpreted as infected cells. Representative “fuschia” cells are as shown within circles in panels B and D.

In summary, these results clearly indicate proliferating CD4+ T cells are selectively being infected and eliminated in all tissues, whereas CD8+ T cells are proliferating (and increasing) at a markedly accelerated pace in tissues in response to infection.

Discussion

Several studies have shown that both HIV and SIV infection result in marked, nonspecific immune activation and cell turnover, and it has been proposed that continual loss of CD4+ T cells results in eventual exhaustion of the capacity for CD4+ T-cell regeneration, leading to the onset of AIDS.17-23 Further, some have proposed that this “chronic” immune stimulation results in overstimulation and “bystander” apoptosis of uninfected CD4+ T cells,24 albeit this does not explain the persistence of activated CD8+ T cells in HIV infection. Indeed, the highest increase in T-cell proliferation was observed in CD8+ T cells, which rapidly expand yet were not depleted until very late (if ever) in the course of HIV-infection. Because both CD4 and CD8+ T cells are “chronically stimulated” it remains unclear why bystander apoptosis would selectively affect only CD4+ cells. In fact, understanding the mechanisms of the early CD4+ T-cell loss remains one of the most critical unanswered questions in HIV pathogenesis.25 Further, because we and others have shown that SIV results in selective depletion of memory CD4+ T cells coexpressing CCR5, much of the early loss of mucosal CD4+ T cells appears the result of direct infection and lysis of these cells.26,27 However, quantifying the contribution of direct infection or bystander apoptosis in tissues is difficult in a dynamic infection such as HIV, particularly when information on the rates of CD4+ T-cell division and turnover in tissues are limited. For example, determining the contribution of direct infection of CD4+ T cells in tissues requires an understanding of T-cell replenishment rates in normal and SIV-infected neonates. In this study, we examined and compared levels of proliferating T-cell subsets in mucosal and peripheral lymphoid tissues of both normal neonatal and adult macaques. The data demonstrate that there are marked differences in rates of T-cell proliferation in tissues of neonates and adults (Figure 1), in that there are marked and sustained levels of ongoing (S-phase) CD4+ T-cell division in neonates compared with adults. Furthermore, most of the proliferating CD4+ T cells in the intestine of neonates coexpress markers of activation (CD69) and memory (CD95) suggesting these are mature cells capable of being infected and supporting viral replication (Figure 2). However, many proliferating cells, especially in the blood, lymph node, and spleen, did not coexpress CD69, verifying that this is not a definitive marker of cell activation. However, proliferating CD4+ T cells are clearly eliminated in a selective manner, as SIV-infected neonates have significantly fewer proliferating CD4+ T cells than their age-matched counterparts. Further, this depletion is accompanied by a marked expansion of CD8+ T cells, and particularly a marked increase in BrdU+ CD8+ T cells, proving that the loss of activated, proliferating cells is specific for cells that express CD4, and that the increased percentages of CD8+ T cells observed is a genuine inflammatory response to SIV infection, rather than an artificial increase reflecting the loss of CD4 cells. Furthermore, confocal microscopy demonstrated that marked numbers of proliferating T cells are productively infected just prior to their depletion in neonatal tissues (Figure 7). Combined, these results prove that SIV selectively infects and destroys dividing CD4+ T cells in neonatal hosts, which almost certainly impairs normal immunologic responses to foreign antigens in the developing neonate. Because CD4+ T-cell proliferation is much more rapid and sustained in neonates than adults, this provides a logical explanation for the sustained viral loads and more rapid disease progression frequently observed in the HIV-infected pediatric host.

Neonatal studies in mice have demonstrated substantial populations of T cells divide in response to “lymphopenia” due to the low levels of lymphocytes in developing neonatal tissues.28 If similar in primates, this “lymphopenia-induced” or “homeostatic” T-cell proliferation could be a major source of dividing T cells in neonates, and may also result in larger proportions of dividing T cells to fuel viral replication.

We have previously shown that neonatal primates are born with a large reservoir of mucosal CD4+ T cells, many of which have an activated, memory phenotype at birth,11 but the data here clearly show that soon after birth, there is a marked and sustained increase in CD4+ T-cell turnover in the intestine, most likely as a result of sudden (and persistent) exposure to dietary or environmental antigens. In fact, early exposure to foreign antigens (ie, food) often results in allergies in human infants, likely due to overstimulation of the immune system. In contrast, intestinal CD4+ T cells of adults have already encountered most of these antigens long ago, and less of a proliferative response, likely to immunologic “tolerance” to these antigens. Thus, once the pool of existing intestinal CD4+ T cells is depleted in adults, plasma viral loads decline, because CD4+ T-cell regeneration is relatively slow in adults, and fewer target cells are produced to support continual viral infection and replication. In contrast, intestinal CD4+ T-cell turnover is markedly accelerated in neonates, which in SIV-infected animals, provides a constant and semirenewable pool of optimal viral target cells, resulting in higher sustained levels of viral replication. The data here however, clearly demonstrate that there is an initial massive and selective depletion of proliferating CD4+ T cells, but when directly comparing precisely age-matched controls, it becomes apparent that SIV-infected macaques are continuously producing CD4+ T cells and struggling to maintain a “threshold” level of CD4+ T cells, despite continuous loss of these cells. Further, and although difficult to prove with certainty, we also show that a much higher proportion of these cells are SIV-infected in early infection, suggesting the mechanism of this loss may be through continuing viral infection and lysis of these cells in tissues. However, we were not able to sort SIV+ or BrdU+ T cells due to technical limitations. We have not found an effective method of sorting SIV+ cells in vivo, nor can we sort BrdU+ cells because its intracellular detection first requires fixation of cells, which interferes with quantitative RNA analyses. Regardless, confocal microscopy of tissues clearly demonstrates a markedly high rate of SIV infection in proliferating T cells (Figure 7).

Finally, and although speculative, we also hypothesize that the accelerated infection and destruction of intestinal CD4+ T cells resulting from this increased turnover in neonates may explain the more rapid progression to disease in HIV-infected infants. It has been proposed that failure to replenish the central memory CD4+ T-cell pool triggers the onset of AIDS in SIV-infected adult macaques.23 Although we and others have shown that failure to maintain a minimum level of intestinal CD4+ T cells results in the onset of AIDS,23,29 the mechanism(s) by which intestinal CD4+ T cells lose the capacity to regenerate remains a mystery. However, if there is a finite pool of intestinal/tissue CD4+ T-cell precursors or stem cells, sustained, selective infection and destruction of dividing CD4+ T cells may explain the more rapid progression to disease in the infected neonatal host, as the constitutively elevated T-cell turnover in neonates may result in a more sustained pool of viral target cells for HIV infection and replication in early infection (explaining sustained high viremia) but also may result in a more rapid exhaustion of a finite precursor pool, resulting in faster progression to AIDS. Furthermore, because proliferating cells are selectively infected, this suggests that early immune responses to environmental antigens may be more significantly impaired in the neonatal host than adults, because most of the responding memory CD4+ T cells are being eliminated practically as fast as they can divide, which almost certainly results in impaired T-cell help in this critical stage of immunologic development. This may be one reason CD8+ T-cell proliferation is not sustained in later SIV infection of neonates (Figure 5), because CD4+ T-cell help is required for sustained CD8+ T-cell responses.30 It is also conceivable that such impairment of CD8+ T cells could also play a role in the sustained plasma high plasma viremia, in addition to the increased CD4+ T-cell proliferation. However, we did not perform immune response assays in these studies and only speculate of impaired immune responses here.

In summary, these data indicate that neonates have markedly increased rates of CD4+ T-cell turnover compared with adults, and these cells are selectively infected and eliminated in early SIV infection, especially in the intestine. The fact that dividing CD4+ T cells are selectively infected may explain many of the differences in the course of neonatal and adult HIV infection including the sustained peak viremia, more rapid progression to AIDS, and perhaps even some of the unique clinical manifestations of pediatric AIDS, including the increased susceptibility of neonates to opportunistic infections, particularly in mucosal tissues.1 If so, perhaps antigenic exposures, through dietary modifications, or other therapeutic approaches may eventually be used in combination with antiretrovirals to help control HIV replication and preserve mucosal immune function in HIV-infected neonatal hosts.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Janell LeBlanc, MaryJane Dodd, and Kelsi Rasmussen for technical support, Calvin Lanclos, Julie Bruhn, and Desiree Waguespack for flow cytometric expertise, and the Tulane National Primate Research Center animal care staff for their excellent animal care.

This work was supported by NIH grants AI062410, AI084793, AI084793, and RR000164.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: X.W. performed and analyzed most experiments; H.X., B.P., and X.A. performed flow cytometry and confocal microscopy, respectively; L.C.G. coordinated experiments, J.D. provided veterinary support; T.M.-R. performed in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry; and A.A.L. and R.S.V. directed the study, provided advice and technical expertise, and assisted with manuscript preparation.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Ronald S. Veazey, Tulane National Primate Research Center, Tulane University School of Medicine, 18703 Three Rivers Rd, Covington, LA 70433; e-mail: rveazey@tulane.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal