Abstract

Interleukin-15 (IL-15) is a cytokine with potential therapeutic application in individuals with cancer or immunodeficiency to promote natural killer (NK)– and T-cell activation and proliferation or in vaccination protocols to generate long-lived memory T cells. Here we report that 10-50 μg/kg IL-15 administered intravenously daily for 12 days to rhesus macaques has both short- and long-lasting effects on T-cell homeostasis. Peripheral blood lymphopenia preceded a dramatic expansion of NK cells and memory CD8 T cells in the circulation, particularly a 4-fold expansion of central memory CD8 T cells and a 6-fold expansion of effector memory CD8 T cells. This expansion is a consequence of their activation in multiple tissues. A concomitant inverted CD4/CD8 T-cell ratio was observed throughout the body at day 13, a result of preferential CD8 expansion. Expanded T- and NK-cell populations declined in the blood soon after IL-15 was stopped, suggesting migration to extralymphoid sites. By day 48, homeostasis appears restored throughout the body, with the exception of the maintenance of an inverted CD4/CD8 ratio in lymph nodes. Thus, IL-15 generates a dramatic expansion of short-lived memory CD8 T cells and NK cells in immunocompetent macaques and has long-term effects on the balance of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.

Introduction

Cytokines belonging to the γ-chain family represent a promising tool for the treatment of certain human diseases in which the immune system is suppressed like HIV or cancer. Thus, boosting immunity in these patients may be beneficial and result in improved treatment. Interleukin-15 (IL-15) is part of the γ-chain family of cytokines and exerts multiple effects on different populations of the immune system. For instance, it is necessary for natural killer (NK)–cell development, since IL-15–deficient mice lack NK cells1,2 ; it acts as an NK growth factor by promoting the differentiation of CD56+ cytokine-producing NK cells to CD56−CD16+ cytotoxic NK cells.3 Conversely, IL-15 is not required for T-cell development but exerts a fundamental role in determining their survival and homeostasis in the periphery. IL-15−/− or IL-15 receptor α chain (IL-15Rα)−/− mice display slightly reduced numbers of naive T cells and a selective deficiency of memory T cells.1,2 Indeed, IL-15 is important for memory T-cell homeostasis as it mediates the expansion and maintenance of memory-phenotype CD8+ T cells4 and the homeostatic proliferation of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells, while survival is mainly mediated by IL-7 in the latter case.4,5 IL-15 also acts on memory CD4+ T cells and cooperates with IL-7 in inducing their expansion in nonlymphopenic conditions.4

A unique biological mechanism governs IL-15 functions in vivo, as the cytokine is transpresented by cells bearing IL-15Rα chain to neighboring cells, which in turn, express CD122 (IL-15Rβ chain) and CD132 (common γ chain, shared by other cytokines such as IL-2, IL-7, IL-9, and IL-21), which are necessary for IL-15 signaling in responding cells6,7 ). Activated monocytes or dendritic cells (DCs) can express IL-15Rα and produce the cytokine at the same time; IL-15 can thus be mounted on the receptor in intracellular compartment and then translocated to the cell surface.6 IL-15Rα on T cells and NK cells is dispensable for IL-15 responsiveness, as IL15Rα-deficient CD8+ T cells behave normally when transferred to wild-type mice.8

Previous studies of IL-15 administration to rhesus macaques (RM) revealed that the cytokine was well-tolerated and did not induce any severe side effect if given subcutaneously.9,10 A recent study in which macaques daily received subcutaneous injections of glycosylated IL-15 (ie, produced in a mammalian system) for a total of 8 days at doses ranging from 2.5 to 15 μg/kg found that animals displayed reversible neutropenia.11 In these reports, IL-15 was able to efficiently expand memory-phenotype T cells and NK cells but, in uncontrolled simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infection, little effect was seen on memory CD4+ T cells.9,10 By contrast, when SIV-uninfected or antiretroviral therapy (ART)–controlled SIV+ monkeys are treated with bacterial-produced IL-15, a strong proliferative burst is observed in the CD4+ transitional or effector memory compartment in the peripheral blood, with little or no effect on other CD4+ subsets10 ; central memory T-cell expansion could be induced after administration of glycosylated IL-15.11 Responding CD4+ and CD8+ cells transiently expanded in the peripheral blood and subsequently localized to the bronchoalveolar space.10

Still, little is known about the kinetics of the response and on the migration/persistence of expanded cells in the whole body. In this paper, we analyzed T- and NK-cell dynamics in multiple tissues upon daily treatment with IL-15 in RM and show that it generates a much more massive expansion of NK and memory T cells compared with previous studies in which an intermittent, twice-a-week administration was considered.9,11,12 Surprisingly, however, expanded cells did not persist for long term. Early after IL-15 initiation, lymphopenia preceded the dramatic expansion of NK cells and memory but not naive T (TN) cells. Memory T cells were predominantly activated and proliferating in multiple tissues and were rapidly released into the peripheral blood along with NK cells. After treatment, expanded cells rapidly disappeared from the blood, thus suggesting redistribution to peripheral tissues, but did not show substantial long-term persistence as T and NK subset proportions were restored 38 days after the last injection. Strikingly, after resolution of this acute effect, IL-15 resulted in a chronically altered balance of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells with CD8+ still outnumbering CD4+ T cells in lymph nodes. Our results reveal previously undescribed short-lasting and long-lasting effects on T-cell homeostasis affected by IL-15 administration and may impact future decisions on human trials.

Methods

Experimental design

Recombinant human interleukin-15 (rhIL-15) was administered intravenously to 8 groups of RM using a computerized randomization procedure. All animal studies were approved by the National Institutes of Health Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (NIH IACUC). The first 4 groups received 10 μg/kg, 20 μg/kg, or 50 μg/kg rhIL-15 intravenously daily from day 1 through day 12, and underwent necropsy on day 13, 1 day after the last dose. Group 4 received formulation buffer (ie, at a volume equivalent on a per kilogram basis to the volume administered to the high-dose group on the same dosing and necropsy schedule as group 1). The remaining 12 animals received 10, 20, and 50 μg of rhIL-15 or formulation buffer at the same dose and dosing schedule with the exception that they underwent necropsy on day 48 (36 days after the last dose). Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis was performed on 7-10 mL of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)–anticoagulated blood 7 days prior to the start of the study and then on days 8 and 13 for the animals killed on day 13 and on 7 days prior to the start of the study and then on days 8, 15, 22, 29, and 48 the date of necropsy.

Preparation of rhIL-15

rhIL-15 was produced under current good manufacturing practice conditions in an Escherichia coli system. rhIL-15 was produced as a nonglycosylated single-chain polypeptide of 115 amino acids having a calculated molecular weight of 12 901 Da. In this work an E coli–based fermentation and purification process was developed for the production of clinical-grade recombinant human IL-15. DNA sequences for human IL-15 inserted into the pET 28 b plasmid were expressed in the E coli host BL 21-AL. The inclusion bodies of IL-15 produced in E coli were solubilized, refolded, and orthogonally purified to yield active IL-15. Purification consisted of orthogonal column chromatography and filtration methods that included Superdex-200 chromatography, refolding of denatured rhIL-15, Butyl HIC chromatography, source 15Q chromatography, Qxl chromatography, and Superdex-75 chromatography to produce the sterile filtered pure drug substance formulated in 25mM sodium phosphate and 500mM sodium chloride, pH 7.4. The sterile filtered bulk drug substance was then filled into vials to produce the final vialed product.

Isolation of MNCs from blood and tissues

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated by Ficoll density gradient centrifugation, according to standard techiniques. At the time of necropsy, the following tissues were collected: mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN), axillary lymph nodes (ALN), inguinal lymph nodes (ILN), spleen (Spl), bone marrow (BM), and jejunum (Jej). Briefly, LN specimens were minced thouroughly, resuspended in RPMI 1640 containing 2 μg/mL collagenase D (Roche), then incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C. Cell suspension was passed multiple times through a 16-gauge needle and then through a 70-μg cell strainer. Spleen was chopped and mashed thoroughly; mononuclear cells (MNCs) were subsequently isolated by Ficoll. Jejunal samples were chopped and digested 3-5 times in R10 (RPMI1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and 1% penicyllin-streptomycin and 1% l-glutamine) containing 0.5 mg/mL collagenase II (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 minutes at 37°C. Supernatant was then layered onto a 35%/65% Percoll gradient for the isolation of MNCs. Cells were immediately frozen in fetal bovine serum plus 10% dimethyl sulfoxide and put in liquid nitrogen until analysis.

Antibodies and flow cytometry

All unconjugated antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences. Nonfluorescent antibodies were conjugated in our laboratory according to the protocols reported at http://www.drmr.com/abcon. Rhesus MNCs were used to titrate reagents. For phenotypic analysis, frozen PBMCs were thawed in R10 containing Benzonase nuclease (EMD Biochemicals), extensively washed and stained immediately with the Violet Viability Dye (ViViD; Invitrogen) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 15 minutes at room temperature (RT). Cells were then washed and stained with the combination of antibodies indicated in supplemental Table 1 (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article) for 20 minutes at RT. Differently, CD132, CCR5, and CCR7 were stained for 20 minutes at 37°C to improve surface detection.13 CD122 expression was revealed by biotin-conjugated antibody followed by staining with streptavin-Qdot 655. For the analysis of intracellular Ki-67 and FoxP3, cells were fixed and permeabilized with the FoxP3 Fixation and Permeabilization Buffer (eBioscience) according to the manufacturer's protocol and subsequently incubated with Ki-67 and FoxP3 antibodies for 30 minutes at 4°C. For the analysis of annexinV expression, cells were resuspended in annexin binding buffer (10mM HEPES [N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid], 140mM NaCl, 2.5mM CaCl2, pH 7.4) and stained with annexinV-phycoerythrin (BD) for 20 minutes at RT. Cells were then fixed and permeabilized with Cytofix/Cytoperm Buffer (BD) according to the manufacturer's protocol to detect intracellular Ki-67. CaCl2 at 2.5mM was included in all steps to avoid the detachment of the annexinV. For the analysis of NKT cells, we incubated cells with the PBS57-loaded CD1d Tetramer (NIAID Tetramer Core Facility) conjugated to allophycocyanin for 10 minutes at room temperature, together with the antibodies listed. Labeled cells were fixed with 0.5% paraformaldehyde and analyzed using a modified LSR II, equipped to detect up to 18 fluorescences. Flow cytometric analysis data were compensated and analyzed with FlowJo software 8.3.6 (TreeStar). Data were formatted with Pestle software (Version 1.6.2) and presented with Spice software (Version 5).

Assessment of T and NK intracellular cytokine production

Frozen cells were thawed in R10 containing benzonase (Novagen) and rested for 4 hours at 37°C before stimulation. For the assessment of T-cell cytokine production, 0.5 × 106 PBMCs were stimulated with 1 μg/mL Staphylococcus enterotoxin B or left unstimulated (dimethyl sulfoxide alone). For the assessment of NK-cell cytokine production, 1.5 × 106 PBMCs were stimulated with the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I–deficient cell line 721.221 at the effector-to-target ratio of 5:1, 100 ng/mL IL-15 and 500 UI IL-2 (both from Peprotech). Cells in medium alone served as control. In both cases, GolgiPlug (BD Biosciences) was added 1 hour later to block cytokine secretion, and cells were cultured for additional 12 hours. Cells were then surface-stained with monoclonal antibodies to lineage antigens, subsequently fixed and permeabilized with Cytofix/Cytoperm buffer (BD). Incubation with antibodies directed to intracellular cytokines (interferon-γ [IFN-γ], tumor necrosis factor-α [TNF-α], and IL-2, or IFN-γ, TNF-α, and macrophage inflammatory protein-1β [MIP-1β] for T- and NK-cell functions, respectively) occurred for 20 minutes at 4°C. The quality of T- and NK-cell cytokine production was analyzed with Spice software, as previously described.14

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Prism Version 4 (GraphPad Software) and Spice software. For most of the comparison, a nonparametric Wilcoxon rank test was used to compare 2 groups of values. In some cases, nonparametric 1-way analysis of variance (Kruskal-Wallis test) was used to compare 3 or more groups. P value was considered significant when < .05.

Results

Transient lymphopenia precedes T- and NK-cell expansion in the peripheral blood

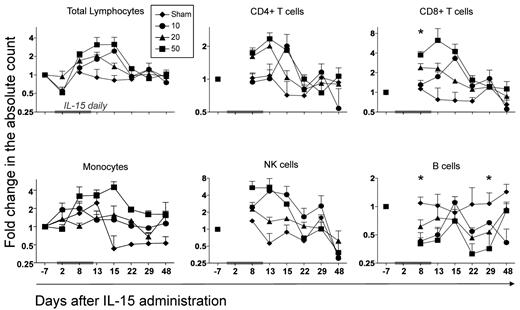

We assessed the effect of 3 different doses of daily recombinant human IL-15 administered intravenously for 12 days in a cohort of 24 Indian RM. The cytokine was well-tolerated with no major side effects. The only clinical meaningful abnormality observed in the toxicology study was a grade 3/4 neutropenia in approximately half of the animals receiving 20- or 50-μg/kg doses. The neutropenia observed only during the course of IL-15 therapy appears to represent a redistribution of neutrophils from the blood pool to the tissues. A complete description of the pathology and toxicity is presented elsewhere (T.A.W., manuscript in preparation). We next assessed the effect of the cytokine on the absolute lymphocyte count in the peripheral blood. As shown in Figure 1, IL-15–treated macaques displayed a decrease in the peripheral lymphocyte count at day 2 after injection, which then increased at day 8, reached its maximum peak at day 13 or day 15, returned to baseline at day 22 and remained stable for the remaining follow-up period. A similar kinetic was observed for the absolute count of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells and NK cells. Expansion was cell-type dependent, yielding a more dramatic expansion in total NK cells and CD8+ T cells (approximately 6-fold expansion compared with pretreatment for both populations), than for total CD4+ T cells (approximately 2.5-fold increase). Surprisingly, B-cell counts decreased in the peripheral blood with the same kinetic after initiation of the treatment and only recovered at day 48, while the CD14+ monocyte was mildly increased. Notably, we did not see a consistent dose-dependent relationship to these dynamics between 10 and 50 μg/kg.

IL-15 administration alters the peripheral blood count of multiple lymphocyte subsets. IL-15 was administered daily for a total of 12 days, at 3 different doses: 10 μg/kg (●), 20 μg/kg (▲), and 50 μg/kg (■). Animals treated with placebo alone (♦) were included as control. Each point corresponds to the mean ± SEM and indicates the fold change in the absolute count relative to day −7 before treatment and is depicted with log scaling. Values for the absolute lymphocyte, CD4+ and CD8+ (CD3+) T-cell, monocyte, NK-cell (defined as CD3−CD14−CD20− and either CD56+ or CD16+), and CD20+ B-cell counts are shown. Total lymphocyte and monocyte counts were obtained from the complete blood counts, while all other subpopulations were calculated by multiplying the percentages obtained from flow cytometric data to the complete blood counts. The gray bar on the x-axis of each graph indicates the time frame of IL-15 therapy. *P < .05 for Wilcoxon rank test in all IL-15–treated animals versus sham. By analyzing single-dose groups independently, we saw a statistical significant increase in NK, CD8+, and CD4+ T cells at day 8 and in NK and CD8+ T cells at day 13 after 1-way analysis of variance test (data not shown).

IL-15 administration alters the peripheral blood count of multiple lymphocyte subsets. IL-15 was administered daily for a total of 12 days, at 3 different doses: 10 μg/kg (●), 20 μg/kg (▲), and 50 μg/kg (■). Animals treated with placebo alone (♦) were included as control. Each point corresponds to the mean ± SEM and indicates the fold change in the absolute count relative to day −7 before treatment and is depicted with log scaling. Values for the absolute lymphocyte, CD4+ and CD8+ (CD3+) T-cell, monocyte, NK-cell (defined as CD3−CD14−CD20− and either CD56+ or CD16+), and CD20+ B-cell counts are shown. Total lymphocyte and monocyte counts were obtained from the complete blood counts, while all other subpopulations were calculated by multiplying the percentages obtained from flow cytometric data to the complete blood counts. The gray bar on the x-axis of each graph indicates the time frame of IL-15 therapy. *P < .05 for Wilcoxon rank test in all IL-15–treated animals versus sham. By analyzing single-dose groups independently, we saw a statistical significant increase in NK, CD8+, and CD4+ T cells at day 8 and in NK and CD8+ T cells at day 13 after 1-way analysis of variance test (data not shown).

IL-15 preferentially expands CD16+ NK cells and effector memory phenotype T cells

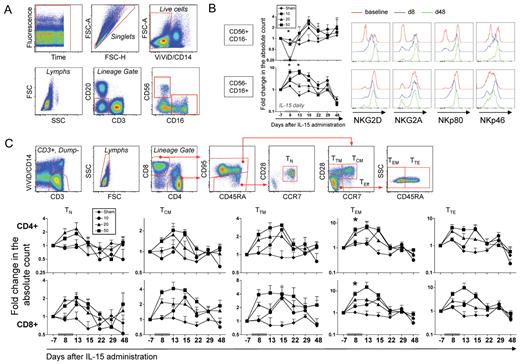

To better define the NK and T-cell subsets that are specifically expanded by IL-15 in RMs, we carried out an extensive analysis of NK and T-cell differentiation status. We used anti-CD56 and anti-CD16 antibodies to identify 2 major NK subsets in the CD3−CD20−CD14− lymphocyte population (ie, CD56+CD16− and CD56−CD16+ NK cells) as depicted in Figure 2A. In humans, CD56+CD16− NK cells represent “regulatory” NK cells that traffic in the LNs and lack cytotoxic potential, while CD16+ NK cells are more differentiated and mediate cytotoxicity.15 Few reports investigated the role of NK cells in the primates, but it is known that cytotoxicity is mainly exerted by the CD16+ NK subset.16 Different kinetics were observed for these NK-cell subsets in the blood (Figure 2B): CD56+CD16− NK cells (but not CD56−CD16+) disappeared from the circulation at day 8 after IL-15 was initiated but reappeared at day 13 and increased in number at day 15. By contrast, an approximate 8-fold expansion of CD56−CD16+ NK cells could be observed in the group receiving 50 μg/kg as soon as day 8 and was maintained until day 15 (3 days after the last IL-15 dose). The absolute count of both subsets returned to baseline 1 week later and remained stable for the remaining follow-up period. Evaluation of multiple NK receptor expression (the lectin-type receptor NKG2D [activatory] and NKG2A [inhibitory]; the natural cytotoxicity receptor NKp46; the C-type lectin receptor NKp80) on a subset of animals (n = 2) receiving 50 μg/kg/d IL-15 (Figure 2B, one representative animal is shown) revealed that IL-15 induced their up-regulation especially in the CD56+CD16− subset. No differences could be observed in the CD56−CD16+ cells, as they were receptor-positive even at baseline.

IL-15 administration expands multiple subsets of NK and memory T cells. (A) Gating strategy used for the identification of NK-cell subsets. A first gate on time versus fluorescence was drawn to exclude artifacts and singlets were selected on the basis of FSC-A and FSC-H. Monocytes and dead cells were excluded by gating on CD14–/ViViD– cells. Within the lymphocyte gate, NK cells were defined as those negative for CD3 and CD20 and positive for either CD56 or CD16. Two major NK-cell subsets could be identified in the RM: CD56+CD16− and CD56−CD16+ NK cells. (B) Left, dynamics of NK-cell subsets after treatment with IL-15. Data from the different dose groups were indicated as in Figure 1. Right, 1 representative example of the dynamics of NKG2D, NKG2A, NKp80, and NKp46 expression in a RM receiving the 50-μg/kg/d dose. Data relative to baseline, day 8 and day 48 after treatment are shown from the 2 identified subsets of NK cells. (C) Gating strategy used for the identification of naive and memory T-cell subsets. Monocytes and dead cells were excluded as in panel A, and T cells were further selected for CD3+ positivity. Within the lymphocyte gate, CD4+ and CD8+ cells were identified (CD8+ T cells only are shown for more clarity). For both lineages, total memory cells are defined as those expressing CD95, while CD95- (almost exclusively CD45RA bright) naive (TN) cells are further restricted as CD28+ and CCR7+. Within the memory cell gate, central memory (TCM) are CCR7+CD28+, transitional memory (TTM) are CCR7–CD28+, and total effectors (TEff) are CCR7–CD28– and could be then subdivided into effector memory (TEM; not expressing CD45RA) or terminal effectors (TTE, expressing CD45RA). (B) Dynamics of TN and memory T-cell subset counts in the peripheral blood after treatment with IL-15. Data from the different dose groups are shown as in Figure 1. *P < .05 for Wilcoxon rank test in IL-15–treated versus sham.

IL-15 administration expands multiple subsets of NK and memory T cells. (A) Gating strategy used for the identification of NK-cell subsets. A first gate on time versus fluorescence was drawn to exclude artifacts and singlets were selected on the basis of FSC-A and FSC-H. Monocytes and dead cells were excluded by gating on CD14–/ViViD– cells. Within the lymphocyte gate, NK cells were defined as those negative for CD3 and CD20 and positive for either CD56 or CD16. Two major NK-cell subsets could be identified in the RM: CD56+CD16− and CD56−CD16+ NK cells. (B) Left, dynamics of NK-cell subsets after treatment with IL-15. Data from the different dose groups were indicated as in Figure 1. Right, 1 representative example of the dynamics of NKG2D, NKG2A, NKp80, and NKp46 expression in a RM receiving the 50-μg/kg/d dose. Data relative to baseline, day 8 and day 48 after treatment are shown from the 2 identified subsets of NK cells. (C) Gating strategy used for the identification of naive and memory T-cell subsets. Monocytes and dead cells were excluded as in panel A, and T cells were further selected for CD3+ positivity. Within the lymphocyte gate, CD4+ and CD8+ cells were identified (CD8+ T cells only are shown for more clarity). For both lineages, total memory cells are defined as those expressing CD95, while CD95- (almost exclusively CD45RA bright) naive (TN) cells are further restricted as CD28+ and CCR7+. Within the memory cell gate, central memory (TCM) are CCR7+CD28+, transitional memory (TTM) are CCR7–CD28+, and total effectors (TEff) are CCR7–CD28– and could be then subdivided into effector memory (TEM; not expressing CD45RA) or terminal effectors (TTE, expressing CD45RA). (B) Dynamics of TN and memory T-cell subset counts in the peripheral blood after treatment with IL-15. Data from the different dose groups are shown as in Figure 1. *P < .05 for Wilcoxon rank test in IL-15–treated versus sham.

T-cell differentiation status was revealed by the simultaneous analysis of CD45RA, CD95, CCR7, and CD28 antigens in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, as depicted in Figure 2C. Figure 2D shows that the absolute counts of all CD4+ and CD8+ memory subsets were expanded upon cytokine treatment. However, effector memory T cells (TEM) with an approximately 8-fold increase compared with pretreatment expanded the most. The kinetics of expansion mirrored those observed for total CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell counts, with a peak observed at day 13 after the first administration. Little effect was observed on CD4+ and CD8+ TN cells, compared with other memory subsets (approximately 2-fold expansion at day 13). Interestingly, before treatment, the expression of CD122, but not of CD132, among lymphocyte subsets reflected the hierarchy of expansion in the blood at the peak of expansion (supplemental Figure 1), even though a correlation between CD122 MFI and the expression of Ki-67 at day 8 was not seen (data not shown).

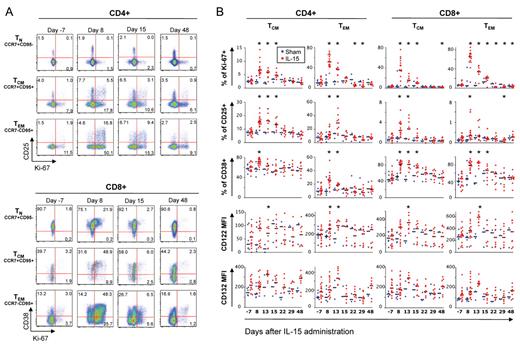

We then evaluated the proliferation and activation state of TN (CCR7+CD95–), central memory T cells (TCM; CCR7+CD95+), and TEM (CCR7–CD95+) CD4+ and CD8+ T cells by measuring the proliferation marker Ki-67 and the activation markers CD38, CD25, HLA-DR, CCR5, and CD122. Figure 3A shows the kinetics of expression of selected markers during IL-15 treatment. As seen for absolute lymphocyte counts, we saw no dose dependence of changes in the measurements and hence pooled IL-15–treated animals. Before administration, few cells were Ki-67+ and CD25+ (among CD4+) or CD38+ (among CD8+). A dramatically increased proportion of TCM, TEM, and, to a lesser extent, CD8+ TN but not CD4+ TN were found to express Ki-67, CD25 (preferentially CD4+) and CD38 (preferentially CD8+) after administration (Figure 3A-B). Up-regulation of these antigens followed the hierarchy of expansion observed in the peripheral blood, that is CD8 > CD4 and TEM > TCM≫TN. IL-15 also induced some of its own receptor subunits in responding cells, as CD122 (IL-15Rβ chain) and CD132 (IL-15Rγ chain) increased during the treatment, then declined after treatment was stopped (Figure 3B). No changes in the expression of CCR5 and HLA-DR were detected (data not shown).

IL-15 treatment preferentially targets memory T cells and induces their proliferation and the expression of multiple activation markers. (A) Representative example of Ki-67, CD25 (only on CD4+ cells, top part of the figure), and CD38 (only on CD8+ cells, bottom part of the figure) expression in a RM receiving 50 μg/kg/d IL-15. Bulk CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were identified as in Figure 2C. Data for different subsets of T cells (TN, defined as CCR7+CD95−; central memory, TCM, as CCR7+CD95+; effector memory, TEM, as CCR7–CD95+) are shown for day −7 (pretreatment), 8, 15, and 48 after the first injection. Numbers in the plots indicate the percentage of cells belonging to each quadrant. (B) Percentage of TCM and TEM CD4+ and CD8+ T cells expressing Ki-67, CD25, and CD38 and mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) values of IL-15 receptor components (CD122 and CD132) in the same subsets during IL-15 therapy. Values for naive T cells are not shown, as little changes could be observed for these markers compared with pretreatment. Horizontal black, bold bars indicate the median. Values from single animals were overlayed and were depicted as blue (sham) or red (IL-15–treated) dots. *P < .05 for Wilcoxon rank test versus day −7.

IL-15 treatment preferentially targets memory T cells and induces their proliferation and the expression of multiple activation markers. (A) Representative example of Ki-67, CD25 (only on CD4+ cells, top part of the figure), and CD38 (only on CD8+ cells, bottom part of the figure) expression in a RM receiving 50 μg/kg/d IL-15. Bulk CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were identified as in Figure 2C. Data for different subsets of T cells (TN, defined as CCR7+CD95−; central memory, TCM, as CCR7+CD95+; effector memory, TEM, as CCR7–CD95+) are shown for day −7 (pretreatment), 8, 15, and 48 after the first injection. Numbers in the plots indicate the percentage of cells belonging to each quadrant. (B) Percentage of TCM and TEM CD4+ and CD8+ T cells expressing Ki-67, CD25, and CD38 and mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) values of IL-15 receptor components (CD122 and CD132) in the same subsets during IL-15 therapy. Values for naive T cells are not shown, as little changes could be observed for these markers compared with pretreatment. Horizontal black, bold bars indicate the median. Values from single animals were overlayed and were depicted as blue (sham) or red (IL-15–treated) dots. *P < .05 for Wilcoxon rank test versus day −7.

Long-term changes of the cytokine production capacity of NK cells after IL-15 treatment

We next evaluated the quality of the cytokine production of T and NK cells after polyclonal stimulation by simultaneously evaluating 3 functions (ie, IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-2 for T cells and IFN-γ, TNF-α, and MIP-1β for NK cells). Supplemental Figure 2A shows that IL-15 treatment did not change the proportion of cytokine-producing Staphylococcus enterotoxin B-reactive T cells nor the quality of the T-cell response, as revealed by the analysis of all possible combinations of cytokine producing cells (supplemental Figure 2B). By contrast, treatment had a major impact on the proportion of NK-responding cells and on the quality of the NK-cell response. After stimulation of NK cells with the MHC class I–deficient 721.221 cell line, cytokine production was confined to a population of CD3–CD14–CD20– NK cells expressing both CD8α and NKG2D (data not shown). Interestingly, a population of cells lacking both CD56 and CD16 also secreted cytokines, in addition to the canonical CD56+CD16− and CD56−CD16+ NK cells (supplemental Figure 2). Furthermore, IL-15 treatment diminished the proportion of responding CD56+CD16− and increased the proportion of CD56−CD16− responding cells by day 8, with no impact on CD56−CD16+ cells (supplemental Figure 2C). With regard to the quality of the NK response, the least differentiated (CD56+CD16−) cells mainly produced IFN-γ but showed no changes in the proportion of cells producing different cytokines (data not shown). By contrast, IL-15 treatment had a long-term impact on CD56−CD6– NK cells; MIP-1β single-producing cells were significantly expanded, and the composition of the response was still different at day 48 after treatment, when homeostasis was restored (supplemental Figure 2D). Finally, CD56−CD16+ displayed less IFN-γ single-producing cells and more MIP-1β single-producing cells (supplemental Figure 2E). Thus, on the basis of cytokine production, it appears that NK cells differentiate from IFN-γ producing to MIP-1β producing cells, with IL-15 treatment resulting in major, long-term changes in the representation of these differentiated cell types.

IL-15 expands CD4+CD25+FoxP3+CD127– cells

Recent data in vivo suggested that IL-15 is able to expand T cells with little effect on the regulatory T-cell (Treg) pool,11 while in vitro studies reported that IL-15 promotes the expansion of these cells isolated from the skin17 or induce the de novo expression of FoxP3 from peripheral blood CD4+CD25 cells.18,19 However, these cells were characterized by weak suppressor activity.18,19 We monitored the frequency of Tregs, defined as CD4+CD25+FoxP3+CD127– (supplemental Figure 3A). Supplemental Figure 3B shows that IL-15 efficiently expanded Tregs in the blood by approximately 3-fold with the same kinetics observed for other T-cell subsets. The majority of Tregs was Ki-67+ even before treatment with IL-15 and their proportion augmented after cytokine administration. Increase in the frequency of this population was also observed in all tissues at day 13, and they were found to be proliferating, as revealed by the increased Ki-67 expression (supplemental Figure 3C). However, their proportion and Ki-67 expression did not differ from control animals at day 48 after treatment, indicating that there was no preferential long-term expansion of Tregs over conventional T cells with restoration of homeostasis (supplemental Figure 3C).

The markers used in this study to define Treg cells can, at least in humans, be induced after T-cell activation. For this reason, it is possible that expansion of the phenotypic Treg cells might just reflect T-cell activation and proliferation induced by treatment with the cytokine. To test this hypothesis, we correlated the percentage of Tregs in tissues at day 13 with the fraction of TCM or TEM CD4+ or CD8+ T cells that expressed Ki-67 or CD38 at the same time point and found no direct correlation (data not shown). In the blood, the increased count of Tregs did not influence expansion of T-cell subsets, as no correlation was found with the fold increase in the absolute of TCM or TEM cells at day 8 after the initiation of the treatment (data not shown). These data suggest that IL-15 might act directly on the subset of naturally occurring Tregs but their increased frequency does not limit expansion of conventional T-cell subsets.

Effect of IL-15 administration on DC subsets and NKT cells

The frequency of DC subsets (ie, myeloid DCs [mDCs] and plasmacytoid DCs [pDCs]) were also monitored in the peripheral blood and in different body sites. pDCs and mDCs were identified as depicted in supplemental Figure 4A. Supplemental Figure 4B shows that mDC cell count increased after IL-15 treatment and then returned to baseline after treatment was stopped. By contrast, pDC cell count decreased at day 8, suggesting redistribution to other tissues, and normalized at day 15. DC subsets were thus investigated in multiple tissues at day 13 and day 48 after treatment, but no changes were detected at these time points (data not shown). IL-15 treatment did not induce maturation of mDCs and pDCs, as revealed by the measurement of CD80 and CD86 molecules on their surface (data not shown). IL-15 can be produced by DCs or monocytes and transpresented to target cells after being mounted on IL-15Rα and expressed on the cell surface.6 However, we did not observe any modulation of the receptor expression on these cells, and we failed to see the expression of the cytokine on their surface using an anti–IL-15 monoclonal antibody (data not shown).

We also evaluated whether IL-15 was able to preferentially expand NKT cells, defined as CD14–CD20–CD3+ Vα24+ that bind to the PBS57-CD1d tetramer, but saw no changes in proportion or cell counts during and after treatment in the peripheral blood (supplemental Figure 4C) of 3 animals receiving 10 or 20 μg/kg or in the spleen of 3 animals receiving 50 μg/kg compared with sham animals at day 13 posttreatment (data not shown). Similarly, the proportion of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells expressing the NK markers CD56 and CD16 did not change with treatment in the PB and tissues (data not shown).

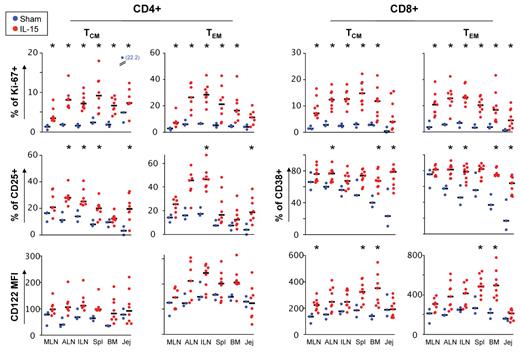

IL-15 primes memory T cells and CD56−CD16+ NK cells in peripheral tissues and induces differentiation of TCM cells

To better understand the dynamics of memory T cells in vivo, we analyzed the activation and proliferation state of TN, TCM, and TEM CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell subsets in different tissues at day 13 after initiation of IL-15 administration along with the fine characterization of T-cell differentiation state. Overall, results were very similar to that seen in the blood. In response to IL-15 we saw a strong up-regulation of Ki-67 (both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells; Figure 4) and of CD25 (in CD4+ T cells and TCM CD8+ cells; Figure 4 and data not shown, respectively), CD38 (in CD8+ but not in CD4+ T cells; Figure 4) and CD122 (both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells; Figure 4). In contrast, HLA-DR, CCR5, and CD132 were not modulated by IL-15 (data not shown). The hierarchy of stimulation mirrored that in the blood, with up-regulation of these markers occurring more frequently in CD8+ than in CD4+ T cells and more in TEM than in TCM (Figure 4). Little effect could be seen in the TN population and was confined to a slight up-regulation of Ki-67 and CD122 within CD8+ TN cells (supplemental Figure 5). Generalized immune activation in multiple body sites along with lymphopenia observed at day 2 indicate that lymphocytes are stimulated in peripheral tissues prior to release into the circulation. Strikingly, analysis of T-cell activation in the same organs at day 48 after treatment initiation revealed no induction of activation markers by T-cell subsets in treated animals (supplemental Figure 6 and data not shown, respectively), demonstrating resolution of the effect of IL-15.

Activation and proliferation of memory T cells after treatment with IL-15 occurs in multiple tissues. Frequency of TCM (CCR7+CD95+) and TEM (CCR7−CD95+) T cells expressing Ki-67 and CD25 (CD4+) or Ki-67 and CD38 (CD8+) in different tissues of the body at day 13 after IL-15 treatment initiation. Expression of CD122 (MFI) was also shown in the same cell subsets. Data were expressed as in Figure 3B. MLN, mesenteric lymph node; ALN, axillary lymph node; ILN, inguinal lymph node; Spl, spleen; BM, bone marrow; Jej, jejunum. *P < .05 after Wilcoxon rank test versus sham.

Activation and proliferation of memory T cells after treatment with IL-15 occurs in multiple tissues. Frequency of TCM (CCR7+CD95+) and TEM (CCR7−CD95+) T cells expressing Ki-67 and CD25 (CD4+) or Ki-67 and CD38 (CD8+) in different tissues of the body at day 13 after IL-15 treatment initiation. Expression of CD122 (MFI) was also shown in the same cell subsets. Data were expressed as in Figure 3B. MLN, mesenteric lymph node; ALN, axillary lymph node; ILN, inguinal lymph node; Spl, spleen; BM, bone marrow; Jej, jejunum. *P < .05 after Wilcoxon rank test versus sham.

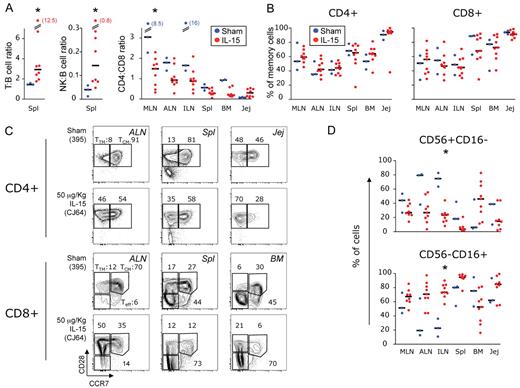

Given the strong proliferation and activation of memory cells in the tissues, especially CD8+ T cells, we expected an increased absolute lymphocyte count in these sites. This was also suggested by an increase at day 13 in both the T:B cell ratio (ie, the ratio between the percentage of cells expressing CD3 and CD20 in the lymphocyte gate) and NK:B-cell ratio (ie, cells expressing either CD56 or CD16 and CD20) in the spleen (Figure 5A) but not in other sites (data not shown). Moreover, perturbation of the CD4:CD8 ratio in favor of CD8+ T cells occurred in the MLN, and a similar trend could be observed in all tissues except the jejunum (Figure 5A). Finally, at the same time point, the spleen and the liver were, respectively 425% and 85% bigger in size in the 50 μg/kg–treated than in the sham-treated macaques, and histological analysis revealed that these organs were infiltrated with lymphocytes (T.A.W., manuscript in preparation). Nonetheless, fine analysis of T-cell differentiation revealed no changes in the proportion of total memory cells (Figure 5B), despite remodeling within the memory compartment (ie, total CD95+ cells), as we observed a decreased proportion of TCM and a parallel increase of TTM or TEM cells (Figure 5C).

Accumulation of CD8+T cells in peripheral tissues is not a consequence of local IL-15–induced expansion. (A) Frequency of T (CD3+) and total NK (either CD56+ or CD16+) cells relative to the frequency of B (CD20+) cells in the lymphocyte gate as observed in the spleen and (B) percentage of CD95+ memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in peripheral tissues at day 13 after treatment initiation. Data are expressed as in Figure 3B and tissue abbreviations are indicated as in “Isolation of MNCs from blood and tissues.” (C) Representative example of the frequency of TCM, TTM, and Teff CD4+ (left) and CD8+ (right) T cells in multiple tissues, as gated on the basis of CCR7 and CD28 expression in CD95+ cells. Animal 395 is shown as a control and animal CJ64 as IL-15–treated. *P < .05 after Wilcoxon rank test versus sham.

Accumulation of CD8+T cells in peripheral tissues is not a consequence of local IL-15–induced expansion. (A) Frequency of T (CD3+) and total NK (either CD56+ or CD16+) cells relative to the frequency of B (CD20+) cells in the lymphocyte gate as observed in the spleen and (B) percentage of CD95+ memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in peripheral tissues at day 13 after treatment initiation. Data are expressed as in Figure 3B and tissue abbreviations are indicated as in “Isolation of MNCs from blood and tissues.” (C) Representative example of the frequency of TCM, TTM, and Teff CD4+ (left) and CD8+ (right) T cells in multiple tissues, as gated on the basis of CCR7 and CD28 expression in CD95+ cells. Animal 395 is shown as a control and animal CJ64 as IL-15–treated. *P < .05 after Wilcoxon rank test versus sham.

The same organs were also investigated at autopsy at day 13 for the presence of NK cells to check whether they were expanded after IL-15 treatment. As in the blood, 2 main subsets of NK cells were quantified (Figure 5D). In IL-15–treated animals, a statistically significant decrease in the proportion of CD56+CD16− cells and a parallel increase in the CD56−CD16+ cells was found in the ALN, with a similar trend in other organs. This suggests that IL-15 induces differentiation of the former NK subset into the latter.

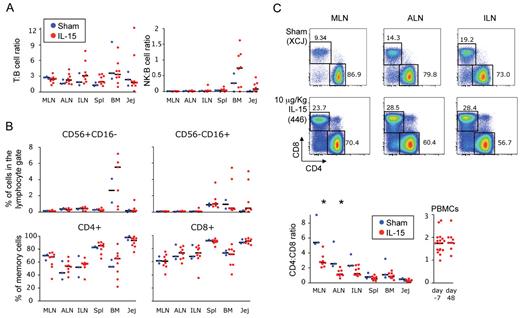

IL-15 generates T and NK cells that do not persist in the body but chronically alters the balance of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells

We showed that IL-15 treatment induced expansion of T and NK cells in the blood as a result of the stimulation in peripheral tissues. NK- and T-cell increases in the blood were transient and declined after IL-15 treatment was stopped (Figures 1–2). Daily doses of IL-15 resulted in a greater expansion of these cells but could not maintain elevated T- and NK-cell counts in the blood. We thus hypothesized that expanded cell subsets selectively localized to peripheral tissues at a later time point. Surprisingly, at day 48, no differences were seen in the proportion of NK cells versus B cells or T cells versus B cells in IL-15–treated animals (Figure 6A). Similarly, in these animals, the percentage of the 2 major subsets of NK cells relative to the total lymphocyte population or the percentage of total memory cells relative to CD4+ or CD8+ subsets did not change in any of the tissues analyzed (Figure 6B). Moreover, no preferential expansion/localization of specific memory T-cell subset could be found in peripheral tissues in animals that received IL-15 (data not shown). These data led us to hypothesize that the concomitant induction of cell death could be induced as a consequence of IL-15 stimulation. To test this, we cultured peripheral blood cells, from 2 animals that received the 50-μg/kg/d dose, with no additional stimuli to mimic cytokine withdrawal in vivo. We analyzed the expression of annexinV (anxV), an early maker of cell death, at 24 and 48 hours. Supplemental Figure 7 shows that the increase in the percentage of Ki-67+ effector memory CD4+ and CD8+ that are also anxV+ follows the IL-15 treatment, suggesting that overactivation in vivo by IL-15 and subsequent withdrawal impairs T-cell survival on specifically expanded subsets.

IL-15 treatment does not lead to long-lasting (day 48) accumulation of NK and memory T cells, but chronically alters the balance of CD4+and CD8+T cells. (A) Frequency of total T (CD3+) cells and NK (either CD56+ or CD16+) cells relative to the frequency of B (CD20+) cells in the lymphocyte gate and (B) percentage of CD56+CD16− NK cells, CD56−CD16+ NK cells, and CD95+ memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells as found in different tissues at day 48 after treatment with IL-15. (C) Top, representative example of the percentage of the CD4+ and CD8+ cells inside the CD3+ gate in the MLN, ALN, and ILN at the same time point. Bottom, CD4:CD8 ratio as found in different tissues and in the PBMCs at day 48 after treatment with IL-15. Data in panels A through C were expressed as in Figure 3B. *P < .05 after Wilcoxon rank test versus sham.

IL-15 treatment does not lead to long-lasting (day 48) accumulation of NK and memory T cells, but chronically alters the balance of CD4+and CD8+T cells. (A) Frequency of total T (CD3+) cells and NK (either CD56+ or CD16+) cells relative to the frequency of B (CD20+) cells in the lymphocyte gate and (B) percentage of CD56+CD16− NK cells, CD56−CD16+ NK cells, and CD95+ memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells as found in different tissues at day 48 after treatment with IL-15. (C) Top, representative example of the percentage of the CD4+ and CD8+ cells inside the CD3+ gate in the MLN, ALN, and ILN at the same time point. Bottom, CD4:CD8 ratio as found in different tissues and in the PBMCs at day 48 after treatment with IL-15. Data in panels A through C were expressed as in Figure 3B. *P < .05 after Wilcoxon rank test versus sham.

Despite most of the homeostatic parameters returned to baseline levels at day 48 after treatment, the CD4:CD8 ratio remained inverted in different sites of the body, such as the MLN or the ALN (P < .05 IL-15 versus sham; Figure 6C) and the same trend could be observed in the ILN. Interestingly, this parameter normalized in other tissues (Figure 6C) and in the peripheral blood (P > .05 IL-15–treated animals at day 48 versus day −7; Figure 6D). These data indicate that IL-15 administration generates T and NK cells that apparently cannot persist for long term, but induces chronic changes in the balance of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the body.

Discussion

The total number of lymphocytes in the body is tightly regulated, and the immune system triggers different homeostatic mechanisms to restore it after acute fluctuations.20 In lymphopenic conditions (eg, after bone marrow or stem cell transplantation) T cells show increased proliferation rates in response to the so-called homeostatic cytokines, mainly IL-7.21 This process is generally slow, and it takes months or even years to bring the total T-cell number back to normality. In some experimental conditions, lymphocyte turnover can be greatly altered such as when T cells are transferred into lymphopenic mice and undergo massive homeostatic proliferation due to high levels of homeostatic cytokines.22 Alteration in the lymphocyte turnover can be also induced by pharmacological doses of cytokines. Indeed, NK and T-cell expansion in response to IL-15 has been previously demonstrated by other studies in RM.9-12 However, the present paper describes 2 novel aspects of IL-15 pharmacology and immunobiology.

First, we demonstrated that a daily administration for 12 days induces a much greater expansion of CD8+ T and NK cells than after the intermittent, twice-a-week administration, as reported in previous studies (approximately 6-fold versus approximately 1.5- to 3-fold).9,11,12 Interestingly, we did not see a dose-dependent effect of the cytokine on the expansion of NK- and T-cell subsets in the PB, with the 10-μg/kg dose being equivalent to the 20-μg/kg dose (Figure 2). Furthermore, at these doses, similar effects on T cells were observed in terms of induction of Ki-67 and multiple activation markers (Figure 3), and in the functionality of T and NK cells (supplemental Figure 2). Moreover, the lack of neutropenia observed after administration of 10 μg/kg IL-15 suggests that this dose could be optimal for inducing NK and T-cell expansion while maintaining minimal side effects in humans.

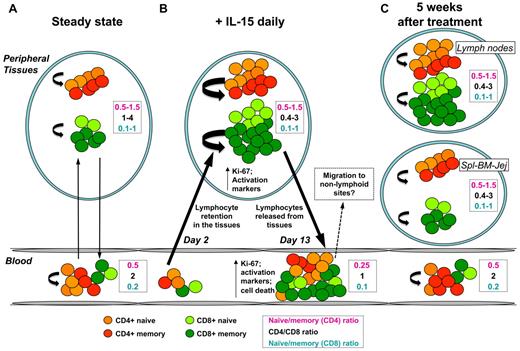

Second, by carefully investigating the complex dynamics of NK and T-cell subsets in multiple tissue specimens at early and late time points after treatment, we show that IL-15 targets NK and memory T cells in several tissues, but expanded cells are short-lived and do not persist for long term. Strikingly, while the naive/memory T-cell balance was rapidly restored after treatment in all tissues analyzed, the CD4:CD8 balance remained altered in the LN, even at day 48 after administration. At day 2 after IL-15 injection, macaques experienced transient lymphopenia (Figure 7B), which preceded T- and NK-cell expansion at day 8. This seems to be a common effect of other cytokines of the γ-chain family, since early lymphopenia has been also described after administration of IL-723,24 and IL-21.25,26 Redistribution of lymphocytes early after therapy thus indicates that stimulation by IL-15 occurs in peripheral tissues rather than in the circulation. Expanded lymphocytes are then rapidly released and account for the increased T- and NK-cell count and for the decreased naive/memory cell balance in the blood (Figure 7B).

Proposed model for IL-15 function in vivo. (A) At the steady state, T-cell subpopulations traffic between the blood and peripheral tissues (black arrows), and their number is kept constant through homeostatic mechanisms (curved arrows). Almost all over the body, CD4+ T cells outnumber CD8+ T cells. (B) Early after IL-15 treatment, trafficking from blood to tissues is altered, and lymphopenia is observed as a consequence of lymphocyte retention in the peripheral tissues (left black arrow). IL-15 greatly increases lymphocyte, especially memory T-cell, cycling (curved arrows), which are activated and express Ki-67. At this time, CD8+ (light and dark green circles) greatly outnumber CD4+ (orange and red circles) T cells. However, IL-15 treatment does not alter the balance of naive and memory T cells in peripheral tissues. Activated lymphocytes are then released into the circulation (right black arrow) and account for the increased lymphocyte count in the blood and for the reduced naive/memory ratio in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. It is like that the increased tendency to undergo apoptosis results from the massive stimulation of these cells or to the withdrawal of cytokine after therapy. (C) After IL-15 treatments were stopped, lymphocyte subpopulation counts are quickly restored in the peripheral blood, probably due to the migration to extra-lymphoid sites. However, the proportion of memory T-cell subsets in blood and tissues are normalized as well, thus suggesting the nonpersistence of expanded cells in the body. Activation and proliferation are dampened, but CD8+ still outnumber CD4+ T cells in the LNs but not in other tissues.

Proposed model for IL-15 function in vivo. (A) At the steady state, T-cell subpopulations traffic between the blood and peripheral tissues (black arrows), and their number is kept constant through homeostatic mechanisms (curved arrows). Almost all over the body, CD4+ T cells outnumber CD8+ T cells. (B) Early after IL-15 treatment, trafficking from blood to tissues is altered, and lymphopenia is observed as a consequence of lymphocyte retention in the peripheral tissues (left black arrow). IL-15 greatly increases lymphocyte, especially memory T-cell, cycling (curved arrows), which are activated and express Ki-67. At this time, CD8+ (light and dark green circles) greatly outnumber CD4+ (orange and red circles) T cells. However, IL-15 treatment does not alter the balance of naive and memory T cells in peripheral tissues. Activated lymphocytes are then released into the circulation (right black arrow) and account for the increased lymphocyte count in the blood and for the reduced naive/memory ratio in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. It is like that the increased tendency to undergo apoptosis results from the massive stimulation of these cells or to the withdrawal of cytokine after therapy. (C) After IL-15 treatments were stopped, lymphocyte subpopulation counts are quickly restored in the peripheral blood, probably due to the migration to extra-lymphoid sites. However, the proportion of memory T-cell subsets in blood and tissues are normalized as well, thus suggesting the nonpersistence of expanded cells in the body. Activation and proliferation are dampened, but CD8+ still outnumber CD4+ T cells in the LNs but not in other tissues.

The increased NK:CD20 ratio and CD3:CD20 ratio in the spleen at day 13 corroborate the suggestion that there is an increased lymphocyte number in peripheral tissues. This is also supported by the fact that, in high dose IL-15–treated animals, the weight of the spleen (increase in size by 425%) or the liver (increase in size by 85%) was much higher than in untreated animals, which was associated with an infiltration of lymphocytes (T.A.W., manuscript in preparation). Notably, all body sites except the jejunum displayed an inverted CD4:CD8 ratio at this time point. This is consistent with the fact that CD8+ T cells are the main targets of IL-15–induced expansion. However, why is the total T-cell pool not increasing in the LNs or in the bone marrow at day 13 despite the inverted CD4:CD8 ratio? Similarly, why is the proportion of memory T cells not increased despite their massive activation and proliferation? Although minimal, IL-15 provoked the expansion of TN cells in the peripheral blood (approximately 2-fold). This could explain, at least in part, the maintenance of the proportions in these sites. These points still require clarification, but it is important to note that similar data have been obtained in a recent trial with IL-7 in macaques, in which generalized migration of T cells occurred in several tissues, but not in the LNs, early after treatment with the cytokine.24

TEM cells seem to be the preferential target of IL-15 stimulation in vivo, as demonstrated by our experiments and by other research groups.9-11 Signaling through the IL-15 receptor is critical for lymphocyte stimulation, and CD122 expression on the cell surface mirrors the expansion in the peripheral blood, with the following hierarchy: NK ∼ CD8+ > CD4+ and TEM > TCM≫TN. Naive T cells responded little to IL-15 in our study, but their proliferation can be induced in other settings in vitro27-29 and in vivo30 in the absence of memory cells. Indeed, both in the blood and in the tissues, a greater fraction of TEM than TCM expressed multiple activation markers and was Ki-67+. However, the increased size of the TEM pool observed in the blood can also be the result of the progressive differentiation of TCM into TEM induced by IL-15, as previously reported in vitro.27,28 Here we demonstrate that this is the case since a generalized differentiation of TCM into TTM or TEM cells occurs in multiple tissues in IL-15–treated animals.

Although we do not have a direct demonstration, we believe that NK-cell stimulation by IL-15 occurs with the same dynamic as for T cells. In this case, it is difficult to determine whether CD56−CD16+ cells are generated from the CD56+CD16− counterpart, although the 2 subsets followed different kinetics shortly after therapy (Figure 2B) and a higher frequency of more differentiated NK cells (ie, CD56−CD16+ NK cells could be found in multiple tissues at day 13; Figure 5C). This is also corroborated by the findings that IL-15 therapy changed the quality of the NK-cell response in CD56−CD16+ NK cells and in the previously undescribed CD56−CD16− NK cells; in both subsets MIP-1β single-producing cells (which are more differentiated) expanded after IL-15 treatment (supplemental Figure 2D-E).

Different from what has been obtained with the administration of other γ-chain cytokines such as IL-2 or IL-7, expansion of IL-15 targets was transient in the peripheral blood and rapidly resolved after treatment was stopped (Figure 7C). Picker et al suggested that effector memory-generated T cells in response to IL-15 in nonhuman primates migrated to the lung, as BrdU-positive memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells could be detected in the bronchoalveolar lavage at least 20 and 30 days after IL-15 administration, respectively.10 We extensively analyzed multiple organs at day 48 after IL-15 treatment (ie, 36 days after the last IL-15 injection) and observed that the proportion of the different subsets of T and NK cells did not differ from untreated animals nor was the proportion of total memory CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell pool increased. In certain tissues, such as the spleen and the jejunum, the naive:memory cell ratio is not a good parameter to determine memory T-cell expansion, since the proportion of naive T cells is too low. However, the CD4:CD8 ratio in these sites at day 48 was not different between IL-15–treated versus sham-treated animals. We did not determine whether migration of NK or memory T cells to peripheral tissues did actually occur after these cells disappeared from the blood. Certainly, we conclude that long-term persistence of expanded memory cells is not a consequence of the daily IL-15 therapy in RM, although the possibility exists that these cells could have migrated to other, noninvestigated tissues, such as the liver, the skin, or the lung, as happens in IL-15 transgenic mice.31 Indeed, massive T-cell proliferation was accompanied by an increased tendency to undergo apoptosis, as demonstrated by the increased frequency of anxV+ cells in the Ki-67+ fraction of effector memory cells, the major target of IL-15. A homeostatic, compensatory mechanism can thus be hypothesized to maintain the number of T cells in the periphery in response to strong proliferative stimuli such as IL-15 or IL-2.32 We do not know whether this mechanism is due to the induction of molecules inducing T-cell death (ie, exogenous) or to cytokine withdrawal (ie, endogenous) and thus to the lack of survival signals, but we exclude a role for FasL in this process as its expression on T cells was negligible and did not change with the treatment (data not shown).

NK-cell and naive and memory T-cell numbers were rapidly restored after acute stimulation in the body. Why then do CD8+ still outnumber CD4+ T cells in the LNs, as demonstrated by the decreased CD4:CD8 ratio at day 48 after treatment (Figure 7C)? It appears that a different kinetic for the regulation of naive/memory balance and CD4/CD8 balance can occur in vivo after acute stimulation. It has been demonstrated that naive and memory cells are independently regulated under physiological conditions, as the number of memory cells in aged mice remains stable despite the profound depletion of naive cells.33,34 CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (with remarkable differences between naive and memory cells) depend on nearly the same factors for their homeostasis, but CD8+ always respond faster and with greater magnitude. This is not only true as in response to IL-15 but also as in response to IL-7.23,24,35,36 This could be explained, at least in part, by the differential expression of CD122 by different CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell subsets, whose baseline values were indicative of the magnitude of expansion at the peak of the response. CD4+ and CD8+ T cells constitute a unique pool and continuously compete for the same homeostatic space. In fact, it is not surprising that a remarkable CD4+ T-cell proliferation in response to IL-15 can occur when the pressure of CD8+ T cells is removed by a CD8+ T-cell–depleting antibody.37 An increased frequency of CD8+ T cells in tissues as induced after treatment with IL-15 could thus favor a preferential survival/engagement of these cells with limited amount of survival factors or homeostatic cytokines, which are known to be present in proximity of stromal cells, especially of those in the LNs.38

In conclusion, IL-15 administration caused a dramatic transient expansion of NK and memory T cells but did not lead to their long-term accumulation in the blood or in peripheral tissues. This acute effect could be achieved by the induction of proliferation and activation of multiple T-cell subsets, mainly of TEM cells. Despite this, chronic changes in the balance of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the LNs were observed after such a treatment, thus suggesting different kinetics for the restoration of homeostasis among lymphocyte subsets. More studies, especially in the context of antigen-specific responses are required to define the mechanisms that differentially govern homeostasis of memory phenotype versus antigen-specific T cells.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Drs Joanne Yu and Pratip Chattopadhyay for assistance with antibody conjugation and qualification; Carl-Magnus Högerkorp, Kaimei Song, and Diane L. Bolton for help with tissue processing; Diego Vargas-Inchaustegui (Vaccine Branch, NCI, Bethesda) for providing the 721.221 cell line; the ImmunoTechnology Section; and Dr Daniel Douek for critical discussions and assistance. The SAIC-Frederick Inc Biopharmaceutical Development Program at the National Cancer Institute at Frederick (NCI-Frederick), Frederick, MD, provided the cGMP rhIL-15 used in this study.

This research was supported by the Intramural Programs of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and the National Cancer Institute, NIH.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: T.A.W. and M.R. conceived and supervised the study; E.L. and C.K.G. performed experiments; J.L.Y. and S.P.C. produced the rhIL-15; L.P.P., J.S., and R.P. provided veterinarian support; E.L., C.K.G., T.A.W., and M.R. analyzed the data; and E.L., T.A.W., and M.R. wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Mario Roederer, Immunotechnology Section, Vaccine Research Center, NIAID, NIH, 40 Convent Dr, Bethesda, MD 20892,; e-mail: roederer@nih.gov.

References

Author notes

T.A.W. and M.R. contributed equally to this study.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal