Abstract

The canonical Wnt signaling pathway is pathogenic in a variety of cancers. We previously identified aberrant expression of the Wnt pathway transcription factor and target gene lymphoid enhancer binding factor-1 (LEF1) in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). This suggested that the Wnt signaling pathway has a role in the biology of CLL. In this study, we performed a Wnt pathway analysis using gene expression profiling and identified aberrant regulation of Wnt pathway target genes, ligands, and signaling members in CLL cells. Furthermore, we identified aberrant protein expression of LEF-1 specifically in CLL but not in normal mature B-cell subsets or after B-cell activation. Using the T cell–specific transcription factor/LEF (TCF/LEF) dual luciferase reporter assay, we demonstrated constitutive Wnt pathway activation in CLL, although the pathway was inactive in normal peripheral B cells. Importantly, LEF-1 knockdown decreased CLL B-cell survival. We also identified LEF-1 expression in CD19+/CD5+ cells obtained from patients with monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis, suggesting a role for LEF-1 early in CLL leukemogenesis. This study has identified the constitutive activation and prosurvival function of LEF-1 and the Wnt pathway in CLL and uncovered a possible role for these factors in the preleukemic state of monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis.

Introduction

B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is a hematologic malignancy characterized by the clonal expansion and significant accumulation of immunophenotypically similar mature B lymphocytes. It is clear that CLL is a disease marked by both increased leukemic cell survival and proliferation.1 Of interest, it has recently been demonstrated that 3% to 5% of the healthy middle-aged adult population has a circulating clonal population of CLL-phenotype B lymphocytes, and this has been designated as monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis (MBL).2,3 It is known that a small percentage of MBL precedes CLL,4-6 similar to the natural history of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance, a documented precursor condition to multiple myeloma.4,7 Therefore, identification of factors that are either shared or divergent between MBL and CLL could provide insight into the molecular features that underlie leukemic transformation and disease progression.

CLL gene expression profiles show similarities with those of memory B cells,8 although there are numerous genes differentially expressed in CLL versus normal B cells. A relevant discovery in CLL B cells was the high level of expression of the transcription factor lymphoid enhancer binding factor-1 (LEF-1).8,9 LEF-1 is a target gene and central mediator of the wingless-type MMTV integration site (Wnt) signaling pathway, suggesting that the Wnt signaling pathway may be active and play a role in the biology of CLL.

LEF-1 is a transcription factor crucial for the proliferation and survival of pro-B cells in the mouse.10 LEF-1 expression is restricted to mouse B-cell precursors, with expression turned off at later stages of B lineage development. Although the normal B-cell expression pattern of LEF-1 in humans remains undefined, it is possible that CLL B cells have reacquired expression of a developmentally important survival factor that normal mature B cells lack. In this regard, it is interesting to note that deregulation of LEF-1 and Wnt activation has been directly linked with the development of leukemia in a mouse model.11

LEF-1 acts as a mediator of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway by recruitment of β-catenin to promoter regulatory elements via an N-terminal binding domain. The canonical Wnt pathway is initiated by binding of soluble glycoprotein Wnt ligands to frizzled family surface receptors along with the coreceptors LRP5/6. These receptors signal through disheveled to block the multimolecular β-catenin destruction complex. Inhibition of the destruction complex allows accumulation of β-catenin with subsequent translocation to the nucleus where it regulates transcription in conjunction with members of the TCF/LEF family. Of interest, the canonical Wnt signaling pathway has been found to regulate genes that control survival and the cell cycle.12-14

Previous studies have evaluated the Wnt pathway in CLL and determined the pathway to be activated.15,16 However, these studies have largely relied on pharmacologic agents to demonstrate that the Wnt pathway is activated in CLL. Small-molecule inhibitors often lack precise specificity, and as such we wished to more definitively determine the role of the Wnt pathway and specifically LEF-1 in CLL biology. Therefore, given the potential role of LEF-1 and the Wnt pathway in the regulation of leukemic development, the aims of this study were to: (1) analyze expression of Wnt signaling pathway members in CLL; (2) determine the LEF-1 expression pattern in normal human B-cell subsets; (3) identify the activation status and functional role of LEF-1 and the Wnt pathway in CLL cells; and (4) identify LEF-1 expression status in the preleukemic state of MBL. Understanding the role of LEF-1 and the WNT pathway in CLL and the precursor state MBL could be of great importance in both understanding the pathogenesis of CLL and in developing unique therapeutic strategies to combat these common conditions.

Methods

Patient cohort

Blood or tissue was collected from healthy donors or patients after informed consent and Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board approval and in accord with the Declaration of Helsinki. Patient clinical and relevant prognostic factors are summarized in Table 1.

Patient cohort characteristics

| Patient no. . | Age, years/sex . | Stage . | CD38 . | ZAP-70 . | Germline homology/VH gene* . | FISH . | Prior treatment . | Assay . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLL 1 | 57/F | Rai 0 | Negative | Negative | Mutated 5.7%, VH 2-26 | 13q− | None | Survival |

| CLL 2 | 72/F | Rai 0 | Negative | ND | Mutated 5.5%, VH 3-53 | Normal | None | Survival |

| CLL 3 | 90/M | Rai I | Positive† | Positive† | Mutated 3.3%, VH 3-07 | 13q− | None | Survival, reporter assay, β-catenin Western blot |

| CLL 4 | 47/F | Rai I | Negative | Negative | Unmutated 1.4%, VH1-02† | Normal | None | Survival and reporter assay |

| CLL 5 | 90/M | ND | Negative | Negative | Mutated 6%, VH 6-0 | 13q− | None | Survival, reporter assay, β-catenin Western blot |

| CLL 6 | 76/M | Rai 0 | Positive† | Negative | Mutated 3.1%, VH 3-15 | Normal | None | Survival and reporter assay |

| CLL 7 | 75/M | ND | Negative | Negative | Mutated 12.9%, VH 4-4 | 17p−†, 13q−, +12† | Yes | Survival and reporter assay |

| CLL 8 | 74/M | Rai I | Negative | Negative | Mutated 2.9%, VH 3-23† | 11q−†, 13q− | None | Survival, reporter assay, β-catenin Western blot |

| CLL 9 | 60/M | Rai II | Negative | Negative | Unmutated 0.8%, VH 4-04† | 13q− | None | Survival, reporter assay, β-catenin Western blot |

| CLL 10 | 61/M | Rai I | Negative | Positive† | Mutated 41%, VH 4-61 | 13q− | None | Reporter assay, β-catenin Western blot |

| CLL 11 | 79/F | ND | Negative | Negative | Unmutated 0%, VH 4-39† | 13q− | None | Reporter assay |

| CLL 12 | 54/M | ND | Negative | Positive† | Unmutated 0%, VH1-69† | 11q−† | Yes | Reporter assay |

| CLL 13 | 57/M | Rai 0 | Negative | Negative | Mutated 8.2%, VH 3-23† | 13q− | None | Reporter assay, β-catenin Western blot |

| CLL 14 | 67/M | Rai II | Negative | Negative | Mutated 5.7%, VH 3-09 | 13q− | None | Reporter assay |

| CLL 15 | 79/M | ND | Positive† | Positive† | Unmutated 0%, VH 1-02† | +12† | None | Reporter assay |

| CLL 16 | 55/M | ND | Negative | Positive† | Mutated 2.6%, VH 3-23† | 13q− | None | Reporter assay |

| CLL 17 | 56/M | Rai 0 | Negative | Negative | Mutated 7.1%, VH 3-11 | Normal | None | Reporter assay |

| CLL 18 | 57/F | Rai I | Negative | Positive† | Unmutated ?, VH ?† | 11q | None | Reporter assay |

| CLL 19 | 53/F | Rai 0 | Negative | Negative | Mutated 8.3%, VH 3-64 | 13q− | None | Long-term culture LEF quantitative PCR |

| CLL 20 | 57/F | Rai 0 | Negative | Positive† | Unmutated 0%, VH 3-33† | 13q− | None | Long-term culture LEF quantitative PCR |

| CLL 21 | 60/M | Rai 0 | Negative | Negative | Mutated 7.5%, VH 2-05 | 13q− | None | IGFBP4 ELISA |

| CLL 22 | 63/F | ND | ND | ND | ND | 13q− | Unknown | IGFBP4 ELISA |

| CLL 23 | Unknown | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | Unknown | IGFBP4 ELISA |

| CLL 24 | 70/F | Rai III | Negative | Negative | Mutated 8.6%, VH 4-04 | 13q− | None | IGFBP4 ELISA |

| CLL 25 | 79/M | Rai I | Positive† | Positive† | Unmutated 0%, VH 1-02† | +12† | None | IGFBP4 ELISA |

| CLL 26 | 64/M | Rai 0 | Negative | Negative | Mutated 11.1%, VH 4-4 | 13q− | None | IGFBP4 ELISA |

| CLL 27 | 54/M | Rai I | Negative | Negative | Mutated 23.1%, VH 4-6 | 13q− | None | LEF flow cytometry |

| CLL 28 | 61/M | Rai IV | Negative | Negative | ND | 13q− | None | LEF flow cytometry and Wnt genes quantitative PCR |

| CLL 29 | 43/M | ND | Negative | Positive† | Unmutated 0%, VH 2-70† | Normal | None | LEF flow cytometry and Wnt genes quantitative PCR |

| CLL 30 | 72/F | Rai II | Positive† | Positive† | Mutated 3%, VH 3-30 | 13q− | None | Wnt genes quantitative PCR |

| CLL 31 | 76/M | Rai III | Positive† | ND | Unmutated 0%, VH 3-30† | +12† | None | Wnt genes quantitative PCR |

| CLL 32 | 66/M | Rai 0 | Negative | ND | Mutated 7.6%, VH 4-59 | 13q− | None | Wnt genes quantitative PCR |

| CLL 33 | 68/M | Rai IV | Positive† | Positive† | Unmutated 0%, VH1-69† | 6q−† | None | Wnt genes quantitative PCR |

| CLL 34 | 49/F | Rai 0 | Negative | Negative | Mutated 9.7%, VH 4-28 | 13q− | None | Wnt genes quantitative PCR |

| CLL 35 | 74/F | Rai III | Negative | ND | Unmutated 0%, VH1-69† | +12† | None | Wnt genes quantitative PCR |

| CLL 36 | 61/M | Rai 0 | Negative | Positive† | Unmutated 0.8%, VH4-59† | +12† | None | LEF Western blot |

| CLL 37 | 68/M | Rai I | Negative | Positive† | Unmutated 0%, VH1-69† | Normal | None | LEF Western blot |

| CLL 38 | 60/F | Rai 0 | Negative | Negative | Mutated 10.1%, VH 1-46 | 13q− | None | LEF Western blot |

| CLL 39 | 49/M | Rai I | ND | ND | Mutated 6.8%, VH 3-23 | 13q− | None | LEF Western blot |

| CLL 40 | 65/M | Rai I | Negative | Negative | Mutated 12.7%, VH 3-15 | 13q−, t(14;18)† | None | LEF Western blot |

| CLL 41 | 75/M | Rai III | Negative | Negative | Mutated 5.4%, VH 4-34 | Normal | None | LEF Western blot |

| CLL 42 | 59/M | Rai I | Positive† | Positive† | Unmutated 0.7%, VH1-24† | 13q− | None | LEF Western blot |

| Patient no. . | Age, years/sex . | Stage . | CD38 . | ZAP-70 . | Germline homology/VH gene* . | FISH . | Prior treatment . | Assay . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLL 1 | 57/F | Rai 0 | Negative | Negative | Mutated 5.7%, VH 2-26 | 13q− | None | Survival |

| CLL 2 | 72/F | Rai 0 | Negative | ND | Mutated 5.5%, VH 3-53 | Normal | None | Survival |

| CLL 3 | 90/M | Rai I | Positive† | Positive† | Mutated 3.3%, VH 3-07 | 13q− | None | Survival, reporter assay, β-catenin Western blot |

| CLL 4 | 47/F | Rai I | Negative | Negative | Unmutated 1.4%, VH1-02† | Normal | None | Survival and reporter assay |

| CLL 5 | 90/M | ND | Negative | Negative | Mutated 6%, VH 6-0 | 13q− | None | Survival, reporter assay, β-catenin Western blot |

| CLL 6 | 76/M | Rai 0 | Positive† | Negative | Mutated 3.1%, VH 3-15 | Normal | None | Survival and reporter assay |

| CLL 7 | 75/M | ND | Negative | Negative | Mutated 12.9%, VH 4-4 | 17p−†, 13q−, +12† | Yes | Survival and reporter assay |

| CLL 8 | 74/M | Rai I | Negative | Negative | Mutated 2.9%, VH 3-23† | 11q−†, 13q− | None | Survival, reporter assay, β-catenin Western blot |

| CLL 9 | 60/M | Rai II | Negative | Negative | Unmutated 0.8%, VH 4-04† | 13q− | None | Survival, reporter assay, β-catenin Western blot |

| CLL 10 | 61/M | Rai I | Negative | Positive† | Mutated 41%, VH 4-61 | 13q− | None | Reporter assay, β-catenin Western blot |

| CLL 11 | 79/F | ND | Negative | Negative | Unmutated 0%, VH 4-39† | 13q− | None | Reporter assay |

| CLL 12 | 54/M | ND | Negative | Positive† | Unmutated 0%, VH1-69† | 11q−† | Yes | Reporter assay |

| CLL 13 | 57/M | Rai 0 | Negative | Negative | Mutated 8.2%, VH 3-23† | 13q− | None | Reporter assay, β-catenin Western blot |

| CLL 14 | 67/M | Rai II | Negative | Negative | Mutated 5.7%, VH 3-09 | 13q− | None | Reporter assay |

| CLL 15 | 79/M | ND | Positive† | Positive† | Unmutated 0%, VH 1-02† | +12† | None | Reporter assay |

| CLL 16 | 55/M | ND | Negative | Positive† | Mutated 2.6%, VH 3-23† | 13q− | None | Reporter assay |

| CLL 17 | 56/M | Rai 0 | Negative | Negative | Mutated 7.1%, VH 3-11 | Normal | None | Reporter assay |

| CLL 18 | 57/F | Rai I | Negative | Positive† | Unmutated ?, VH ?† | 11q | None | Reporter assay |

| CLL 19 | 53/F | Rai 0 | Negative | Negative | Mutated 8.3%, VH 3-64 | 13q− | None | Long-term culture LEF quantitative PCR |

| CLL 20 | 57/F | Rai 0 | Negative | Positive† | Unmutated 0%, VH 3-33† | 13q− | None | Long-term culture LEF quantitative PCR |

| CLL 21 | 60/M | Rai 0 | Negative | Negative | Mutated 7.5%, VH 2-05 | 13q− | None | IGFBP4 ELISA |

| CLL 22 | 63/F | ND | ND | ND | ND | 13q− | Unknown | IGFBP4 ELISA |

| CLL 23 | Unknown | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | Unknown | IGFBP4 ELISA |

| CLL 24 | 70/F | Rai III | Negative | Negative | Mutated 8.6%, VH 4-04 | 13q− | None | IGFBP4 ELISA |

| CLL 25 | 79/M | Rai I | Positive† | Positive† | Unmutated 0%, VH 1-02† | +12† | None | IGFBP4 ELISA |

| CLL 26 | 64/M | Rai 0 | Negative | Negative | Mutated 11.1%, VH 4-4 | 13q− | None | IGFBP4 ELISA |

| CLL 27 | 54/M | Rai I | Negative | Negative | Mutated 23.1%, VH 4-6 | 13q− | None | LEF flow cytometry |

| CLL 28 | 61/M | Rai IV | Negative | Negative | ND | 13q− | None | LEF flow cytometry and Wnt genes quantitative PCR |

| CLL 29 | 43/M | ND | Negative | Positive† | Unmutated 0%, VH 2-70† | Normal | None | LEF flow cytometry and Wnt genes quantitative PCR |

| CLL 30 | 72/F | Rai II | Positive† | Positive† | Mutated 3%, VH 3-30 | 13q− | None | Wnt genes quantitative PCR |

| CLL 31 | 76/M | Rai III | Positive† | ND | Unmutated 0%, VH 3-30† | +12† | None | Wnt genes quantitative PCR |

| CLL 32 | 66/M | Rai 0 | Negative | ND | Mutated 7.6%, VH 4-59 | 13q− | None | Wnt genes quantitative PCR |

| CLL 33 | 68/M | Rai IV | Positive† | Positive† | Unmutated 0%, VH1-69† | 6q−† | None | Wnt genes quantitative PCR |

| CLL 34 | 49/F | Rai 0 | Negative | Negative | Mutated 9.7%, VH 4-28 | 13q− | None | Wnt genes quantitative PCR |

| CLL 35 | 74/F | Rai III | Negative | ND | Unmutated 0%, VH1-69† | +12† | None | Wnt genes quantitative PCR |

| CLL 36 | 61/M | Rai 0 | Negative | Positive† | Unmutated 0.8%, VH4-59† | +12† | None | LEF Western blot |

| CLL 37 | 68/M | Rai I | Negative | Positive† | Unmutated 0%, VH1-69† | Normal | None | LEF Western blot |

| CLL 38 | 60/F | Rai 0 | Negative | Negative | Mutated 10.1%, VH 1-46 | 13q− | None | LEF Western blot |

| CLL 39 | 49/M | Rai I | ND | ND | Mutated 6.8%, VH 3-23 | 13q− | None | LEF Western blot |

| CLL 40 | 65/M | Rai I | Negative | Negative | Mutated 12.7%, VH 3-15 | 13q−, t(14;18)† | None | LEF Western blot |

| CLL 41 | 75/M | Rai III | Negative | Negative | Mutated 5.4%, VH 4-34 | Normal | None | LEF Western blot |

| CLL 42 | 59/M | Rai I | Positive† | Positive† | Unmutated 0.7%, VH1-24† | 13q− | None | LEF Western blot |

CD38+ samples have > 30% positive cells. ZAP-70+ samples have > 20% positive cells. For MBL patients, absolute B-cell counts are as follows: MBL 1, 2.4 × 109/L; MBL 2, 1.7 × 109/L; MBL 3, 1.1 × 109/L; MBL 4, 2.4 × 109/L; MBL 5, 2.0 × 109/L; MBL 6, 0.7 × 109/L; MBL 7, 1.9 × 109/L; MBL 8, 1.5 × 109/L.

F indicates female; M, male; and ND, not determined.

Mutated immunoglobulin heavy chain is > 2% different from germline VH.

Poor prognostic factor.

Cell isolation and culture

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells from CLL patients were separated from heparinized venous blood by Ficoll density gradient centrifugation. The peripheral blood mononuclear cells used in this study were generally greater than 90% CLL B cells (CD19+/CD5+) or were isolated using immunomagnetic B-cell enrichment kits (StemCell Technologies). Leukemic cells were cultured in serum-free adoptive immunotherapy media-V (AIM-V) medium (Invitrogen). Samples from patients with MBL were collected within 3 months of diagnosis among persons with clonal B cells of CLL phenotype and a B-cell count of less than 5 × 109 cells/L (range, 0.7-2.4 × 109 cells/L) at MBL diagnosis.6 Human cord blood, tonsillar, bone marrow, and blood B cells were obtained from healthy subjects by immunomagnetic selection using B-cell enrichment kits and, when indicated, cultured in RPMI with 10% fetal bovine serum. After enrichment, the purity of the CD19+ cells typically exceeded 95%. For normal B-cell activation experiments, B cells were cultured for 24 or 72 hours in media containing 10 μg/mL F(ab′)2 fragment goat anti–human IgA, IgG, IgM (Jackson ImmunoResearch) or 2.5 μg/mL CpG ODN 200617 (synthesized in-house), 9.4 × 104 IU/mL human IL-2 (PeproTech), and 10 ng/mL human IL-15 (PeproTech). Human T cells were isolated from healthy donor peripheral blood by immunomagnetic selection using T-cell enrichment kits (StemCell Technologies). The Colo 320 colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line was kindly provided by Dr Scott Kaufmann at the Mayo Clinic and was maintained in RPMI with 10% fetal bovine serum. All cells were maintained in appropriate media at 37°C in an atmosphere containing 95% air and 5% CO2.

RNA isolation and microarray hybridization

Total RNA was isolated from B cells isolated from 41 untreated CLL and 11 age-matched control samples using Trizol (Invitrogen). RNA quality was assessed on an Agilent bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). cDNA and probe labeling was carried out as previously described.10 Briefly, double-stranded cDNA was synthesized from 8 μg of total RNA, and the purified product was used to create biotin-labeled cRNA by in vitro transcription (Enzo). A total of 15 μg of labeled product was added to a hybridization solution according to the manufacturer's instructions (Affymetrix). The hybridization solution was heated at 99°C for 5 minutes followed by incubation at 45°C for 5 minutes and then centrifuged at high speed for 5 minutes before applying the sample onto Affymetrix U133 A and B chips. Hybridization was performed at 45°C for 16 hours in a rotisserie oven at 60 rpm, after which the solutions were removed, and arrays were washed and stained as described in the Affymetrix GeneChip Expression Analysis Technical Manual. The hybridized arrays were scanned using a GeneChip 3000 scanner and Affymetrix GeneChip Operating System software, Version 1.3, were used to quantitatively analyze the scanned image. All control parameters were confirmed to be within normal ranges before normalization, and data reduction was initiated. The microarray data were uploaded onto the GEO public database with the accession number GSE22529.

Quantitative PCR

Sense and antisense primers to genes of interest were designed using Primer3 and are listed in Table 2. Total RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA using the 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (GE Healthcare). A total of 1 μL of cDNA was amplified using the SYBR Green PCR kit (QIAGEN) in a total volume of 20 μL, which included 0.5μM of each primer and 1 × SYBR Green Mastermix. Amplification was carried out using the Roche Lightcycler 2.0 as follows: denaturation at 95°C for 15 minutes, 40 cycles of 15 seconds at 95°C, 30 seconds at 55°C to 60°C, 30 seconds at 72°C, and a melting curve cycle. The annealing temperature was dependent on the primer pair used. Melting temperature and quantitative analysis was performed using Roche Lightcycler software Version 4. Relative fold change was normalized against β-actin or 18s rRNA after 1:2000 cDNA dilution and calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method.

PCR primers

| Gene . | Primer . |

|---|---|

| LEF1 | Forward-5′-GAC GAG ATG ATC CCC TTC AA-3′ |

| Reverse-5′-AGG GCT CCT GAG AGG TTT GT-3′ | |

| WNT3 | Forward-5′-CCC AGA GAC GGG TTC CTT-3′ |

| Reverse-5′-CTG TGC CCG GCT CTA GGT-3′ | |

| CCND2 | Forward-5′-CTT CCG CAG TGC TCC TAC TT-3′ |

| Reverse-5′-CCA AGA AAC GGT CCA GGT AA-3′ | |

| TCF4 [ITF2] | Forward-5′-CAG ACC AAG CTC CTG ATC CT-3′ |

| Reverse-5′-GCA ATG TGG CAA CTT GGA C-3′ | |

| AICDA | Forward-5′-CCA WTT CAA AAA TGT CCG CTG GGC-3′ |

| Reverse-5′-AGG AGG TGA ACC AGG TGA CGC G-3′ | |

| ACTB | Forward-5′-GGA TCC GAC TTC GAG CAA GAG ATG GCC AC-3′ |

| Reverse-5′-CAA TGC CAG GGT ACA TGG TGG TG-3′ | |

| 18s rRNA | Forward-5′-AAA CGG CTA CCA CAT CCA AG-3′ |

| Reverse-5′-CCT CCA ATG GAT CCT CGT TA-3′ |

| Gene . | Primer . |

|---|---|

| LEF1 | Forward-5′-GAC GAG ATG ATC CCC TTC AA-3′ |

| Reverse-5′-AGG GCT CCT GAG AGG TTT GT-3′ | |

| WNT3 | Forward-5′-CCC AGA GAC GGG TTC CTT-3′ |

| Reverse-5′-CTG TGC CCG GCT CTA GGT-3′ | |

| CCND2 | Forward-5′-CTT CCG CAG TGC TCC TAC TT-3′ |

| Reverse-5′-CCA AGA AAC GGT CCA GGT AA-3′ | |

| TCF4 [ITF2] | Forward-5′-CAG ACC AAG CTC CTG ATC CT-3′ |

| Reverse-5′-GCA ATG TGG CAA CTT GGA C-3′ | |

| AICDA | Forward-5′-CCA WTT CAA AAA TGT CCG CTG GGC-3′ |

| Reverse-5′-AGG AGG TGA ACC AGG TGA CGC G-3′ | |

| ACTB | Forward-5′-GGA TCC GAC TTC GAG CAA GAG ATG GCC AC-3′ |

| Reverse-5′-CAA TGC CAG GGT ACA TGG TGG TG-3′ | |

| 18s rRNA | Forward-5′-AAA CGG CTA CCA CAT CCA AG-3′ |

| Reverse-5′-CCT CCA ATG GAT CCT CGT TA-3′ |

Western blot analysis

Freshly isolated cells were lysed for 30 minutes on ice in lysis buffer containing 10mM Tris (pH 7.4), 150mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 5mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, and complete mini-protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics). An equal volume of Laemmli sample buffer (Bio-Rad) was added before boiling for 5 minutes. Lysates were subjected to electrophoresis through a 10% Tris-HCl polyacrylamide gel using Tris-glycine-sodium dodecyl sulfate buffer. Proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore) and blocked with 25mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.2), 150mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween 20 plus 5.0% Blotto (ISC BioExpress). The blot was probed with anti–LEF-1 and β-catenin antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology) at a 1:1000 dilution, or anti–β-actin antibody (Novus) at a 1:5000 dilution. After 3 washes with 25mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.2), 150mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween 20, donkey anti–rabbit or sheep anti–mouse horseradish peroxidase secondary (GE Healthcare) was used at a 1:2000 dilution. After washing, SuperSignal (Pierce Chemical) chemiluminescent substrate was used to detect proteins.

Flow cytometry

Cells were washed in fluorescence-activated cell sorter buffer (phosphate-buffered saline + 1% fetal calf serum) and incubated with conjugated primary antibody for 15 minutes on ice. Antibodies included anti-CD19 APC, CD5 PE, CD86 PE (BD Biosciences) and LEF-1 (Cell Signaling Technology). For intracellular staining, cells were fixed in 4% formaldehyde/phosphate-buffered saline at 37°C for 10 minutes and permeabilized by resuspending in 90% methanol and incubation on ice for 30 minutes. Cells were incubated with primary antibody or isotype control for 1 hour, washed, and incubated with secondary Alexa 488 goat anti–rabbit IgG (Invitrogen) for 30 minutes. Cells were then analyzed on a BD FACSCalibur and data analysis was performed using FlowJo software Version 7.5 (TreeStar).

ELISA

CLL and normal B cells were cultured at 1 × 107 cells/mL for 72 hours. Cell-free culture supernatants were harvested for IGFBP-4 ELISA (Diagnostic Systems Laboratories) and were analyzed according to the company's protocol along with a standard curve of recombinant IGFBP-4. Samples were measured in duplicate on a 96-well microplate reader (Molecular Devices) and concentrations calculated using Softmax Pro software Version 2.6.1.

TCF/LEF dual luciferase assay

TCF/LEF reporter plasmids were purchased from SA Biosciences. The positive reporter plasmid has TCF/LEF consensus binding sites that drive expression of firefly luciferase, and the negative reporter lacks TCF/LEF binding sites. These plasmids were introduced along with a constitutively expressed Renilla luciferase plasmid into CLL or normal blood B cells using the Nucleofector System (Amaxa Biosystems). For nucleofection, 1 × 107 cells were resuspended in 100 μL of Cell Line Nucleofector Solution V for CLL cells or B Cell Solution for normal B cells and mixed with 1.5 μg of plasmid DNA. Nucleofections were done using the Amaxa Nucleofector II device and the U-013 program for CLL and U-015 program for B cells. To evaluate nucleofection efficiency, an equal number of cells were nucleofected with the GFP-expression vector pmaxGFP (Amaxa Biosystems). Cells were cultured in 24-well plates for 48 hours and then harvested and processed using the Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega). Samples were read on a Centro XS3 plate luminometer (Berthold Technologies). Positive reporter firefly luciferase values were normalized to constitutively expressed Renilla luciferase and a negative reporter fold change of 1.

siRNA and cell survival analysis

siRNAs targeting LEF-1 and a control scrambled siRNA were purchased from Invitrogen. Both siRNAs were designed such that they would inhibit expression of full-length LEF-1 as well as the ΔN isoform. A total of 1.06 μg of siRNA was introduced into 1 × 107 CLL cells via nucleofection as described in “TCF/LEF dual luciferase assay,” and cells were collected and processed for flow cytometry, quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR), or immuno blotting analysis at various time points from 24 to 96 hours after nucleofection. Cell survival was measured by annexin-fluorescein isothiocyanate (BD Biosciences) and propidium iodide staining and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Statistical methods

For gene expression profiling (GEP) data, the data were preprocessed using the GCRMA algorithm, with one exception: instead of using quantile normalization, all microarrays were normalized together using an intensity-dependent normalization procedure.18 To evaluate the differential expression between CLL patients and age-matched controls, a t-statistic was conducted. Genes were evaluated further if they had a P value less than .0001 and a fold change estimate larger than 1.5 (or < 1/1.5 = 0.67). For quantitative PCR, reporter assay data, and change in mean fluorescence intensity of LEF-1, staining comparisons between CLL and control samples were done using an unequal variance t-statistic. For survival data, comparisons were done using a paired t statistic. Fold change in survival was determined by dividing the percentage survival for each treatment by the percentage survival in the control treated sample of each patient.

Results

Deregulation of Wnt pathway gene expression in CLL

We previously identified aberrant expression of the Wnt pathway transcription factor and target gene LEF1 in CLL.9 To further interrogate deregulation of the Wnt pathway in CLL, we performed GEP on 41 previously untreated CLL patients enrolled in a previously published chemoimmunotherapy trial conducted by us19 and compared these with 11 age-matched controls. We queried CLL and control B-cell GEP data for evidence of differential expression of Wnt pathway-related genes (supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). This GEP analysis confirmed that CLL B cells expressed the LEF1 gene at approximately 28-fold higher levels than normal B cells (P < .0001; Table 3). In addition to LEF1 overexpression, 7 other Wnt-related genes met our selection threshold of more than or equal to 1.5-fold change in expression between CLL and control B cells and P values of less than .0001 (Table 3). These additional deregulated genes included a Wnt ligand (WNT3), Wnt target genes (TCF4 [ITF-2], CCND2), and a Wnt inhibitor (IGFBP4). Thus, our data suggest there is significant and complex deregulation of Wnt pathway member genes in CLL.

Deregulation of Wnt pathway gene expression in CLL

| Gene name . | Fold change . | Role in Wnt signaling . |

|---|---|---|

| LEF1 | 28-fold higher in CLL | Pathway transcription factor; target gene |

| IGFBP4 | 19-fold higher in CLL | Secreted pathway inhibitor |

| WNT3 | 6.4-fold higher in CLL | Secreted pathway ligand |

| TCF4 (ITF2) | 4-fold higher in CLL | Target gene |

| JUN | 3.2-fold higher in control | Nuclear regulator |

| CCND2 | 2.4-fold higher in CLL | Target gene |

| CTBP2 | 2.2-fold higher in control | Corepressor of Wnt target genes |

| CSNK1D | 1.9-fold higher in control | Pathway kinase |

| Gene name . | Fold change . | Role in Wnt signaling . |

|---|---|---|

| LEF1 | 28-fold higher in CLL | Pathway transcription factor; target gene |

| IGFBP4 | 19-fold higher in CLL | Secreted pathway inhibitor |

| WNT3 | 6.4-fold higher in CLL | Secreted pathway ligand |

| TCF4 (ITF2) | 4-fold higher in CLL | Target gene |

| JUN | 3.2-fold higher in control | Nuclear regulator |

| CCND2 | 2.4-fold higher in CLL | Target gene |

| CTBP2 | 2.2-fold higher in control | Corepressor of Wnt target genes |

| CSNK1D | 1.9-fold higher in control | Pathway kinase |

P < .0001 for all.

To verify the GEP data, we performed quantitative PCR for LEF1, WNT3, TCF4 [ITF-2], and CCND2 on samples from 8 CLL patients and 3 normal peripheral B-cell samples. These assays confirmed that CLL B cells expressed significantly higher levels of each gene than did normal B cells (Figure 1A). Next, we performed an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to detect IGFBP4 secretion into culture supernatants and found that the majority of CLL samples secreted detectable levels of this factor, whereas normal B cells do not (Figure 1B). Because of these results, we wished to further study the role of LEF-1 and the Wnt pathway in CLL pathogenesis.

Deregulation of Wnt pathway gene expression in CLL. (A) Detection of LEF1, WNT3, TCF4 [ITF-2], and CCND2 mRNA levels by quantitative PCR in leukemic or normal B cells from 8 CLL patients and 3 healthy donor samples, respectively. Transcript levels were normalized to 18s rRNA, and relative fold change was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method. *P < .05. Error bars represent SEM. (B) Detection of IGFBP-4 protein secretion into culture media by ELISA in B cells from 6 CLL patients and 3 healthy donor samples. The dashed line at 5 ng/mL indicates the ELISA threshold level of IGFBP-4 detection, and the horizontal lines indicate the mean of each group.

Deregulation of Wnt pathway gene expression in CLL. (A) Detection of LEF1, WNT3, TCF4 [ITF-2], and CCND2 mRNA levels by quantitative PCR in leukemic or normal B cells from 8 CLL patients and 3 healthy donor samples, respectively. Transcript levels were normalized to 18s rRNA, and relative fold change was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method. *P < .05. Error bars represent SEM. (B) Detection of IGFBP-4 protein secretion into culture media by ELISA in B cells from 6 CLL patients and 3 healthy donor samples. The dashed line at 5 ng/mL indicates the ELISA threshold level of IGFBP-4 detection, and the horizontal lines indicate the mean of each group.

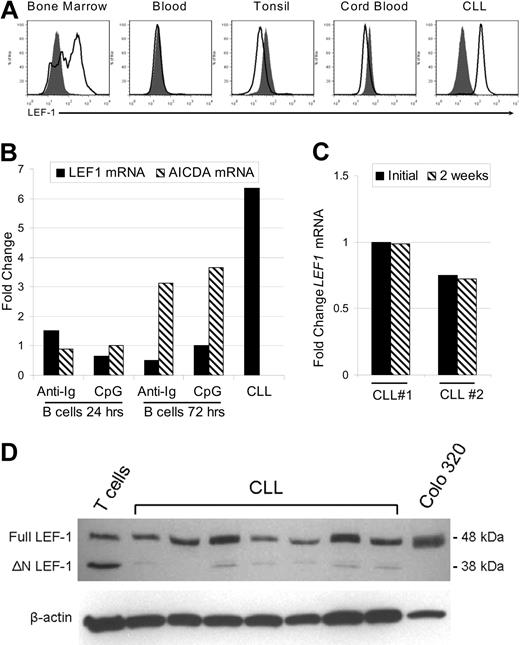

LEF-1 protein is specifically expressed by B-cell precursors and CLL cells but not mature peripheral B-cell subsets

In the mouse, LEF-1 has been implicated as a crucial factor during the pre- and pro-B cell stages of development in the bone marrow, although its expression is lost in mature B cells.10 LEF-1 expression in normal human B-cell subsets has not yet been reported. Thus, we next assessed LEF-1 expression in CD19+ purified human B cells from bone marrow, peripheral blood, tonsil, and cord blood. These tissues were selected because they contain precursor, mature, germinal center, and CD19+/CD5+ lineage B cells, respectively. In addition, although we have shown that CLL B cells express LEF1 mRNA, it remained possible that only a subset of CLL B cells express this gene. To address these issues, we used a flow cytometric method that permits detection of intracellular staining for LEF-1. First, we demonstrated that LEF-1 was expressed by a subset of CD19+ bone marrow B cells (Figure 2A). Bone marrow B cells expressing LEF-1 probably represent B-cell precursors as we found that LEF-1 expression was lost in mature B cells in the peripheral blood, tonsil, and CD19+/CD5+ cord blood B cells (Figure 2A). CLL B cells, in contrast, uniformly expressed LEF-1, and there was no indication of highly positive or negative subpopulations (Figure 2A).

LEF-1 protein is specifically expressed by B-cell precursors and CLL cells but not mature peripheral B-cell subsets. (A) Representative intracellular flow cytometry for LEF-1 in B cells from healthy donor bone marrow, blood, tonsil, cord blood, and CLL B cells from a CLL patient. Isotype control histogram is shaded gray; LEF-1 histogram is black. (B) Detection of LEF1 and AICDA mRNA levels by quantitative PCR in B cells from a healthy donor at 24 and 72 hours after stimulation with CpG and cytokines or anti-immunoglobulin (anti-Ig) stimulation. Fold change was calculated relative to unstimulated donor B cells; an unstimulated CLL sample served as a positive control for LEF-1 expression. (C) Detection of LEF1 mRNA levels by quantitative PCR in 2 CLL patients before and after 2 weeks in culture in AIM-V media at a density of 10 × 106 cells/mL. (D) Western blot analysis of LEF-1 isoforms in B cells from 7 CLL samples; T cells from a healthy donor and Colo 320 cells served as a control for LEF-1 isoforms. β-Actin shown as a loading control of samples.

LEF-1 protein is specifically expressed by B-cell precursors and CLL cells but not mature peripheral B-cell subsets. (A) Representative intracellular flow cytometry for LEF-1 in B cells from healthy donor bone marrow, blood, tonsil, cord blood, and CLL B cells from a CLL patient. Isotype control histogram is shaded gray; LEF-1 histogram is black. (B) Detection of LEF1 and AICDA mRNA levels by quantitative PCR in B cells from a healthy donor at 24 and 72 hours after stimulation with CpG and cytokines or anti-immunoglobulin (anti-Ig) stimulation. Fold change was calculated relative to unstimulated donor B cells; an unstimulated CLL sample served as a positive control for LEF-1 expression. (C) Detection of LEF1 mRNA levels by quantitative PCR in 2 CLL patients before and after 2 weeks in culture in AIM-V media at a density of 10 × 106 cells/mL. (D) Western blot analysis of LEF-1 isoforms in B cells from 7 CLL samples; T cells from a healthy donor and Colo 320 cells served as a control for LEF-1 isoforms. β-Actin shown as a loading control of samples.

Because CLL B cells more closely resemble activated B cells, we next determined whether LEF1 expression could be the result of B-cell activation. As shown in Figure 2B, normal B cells failed to up-regulate LEF1 after either stimulation with B-cell receptor cross-linking antibodies (anti-Ig) or stimulation through TLR9 using CpG and cytokines. Evidence that these stimuli indeed induced B-cell activation was obtained through studies showing that CD86 expression was up-regulated (data not shown) and also that activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AICDA) mRNA was increased at 72 hours after stimulation (Figure 2B). Our data suggest that LEF1 expression in CLL B cells does not reflect activation status and is instead related to intrinsic changes associated with transformation. As further evidence of an intrinsic defect leading to aberrant LEF1 expression, we cultured CLL cells for 2 weeks in serum-free AIM-V media and assayed for LEF1 mRNA via quantitative PCR. These studies revealed that the cells retained LEF1 expression after long-term culture (Figure 2C). These data support the conclusion that LEF-1 is constitutively expressed in CLL B cells, and maintained expression does not depend on ongoing stimulation by signals extrinsic to the leukemic B cell.

The LEF1 locus uses differential promoters to turn on isoforms of the gene that have opposing function in Wnt signaling.20 Full-length LEF-1 is able to mediate β-catenin-dependent gene regulation and is predominately expressed in certain cancers, whereas the opposing dominant negative short isoform (ΔN LEF-1) is found at greater levels in normal lymphocytes. ΔN LEF-1 disrupts canonical Wnt signaling because it lacks the LEF-1 β-catenin binding domain but retains DNA binding activity. Western blot analysis revealed that CLL B cells predominantly expressed full-length LEF-1 (Figure 2D). As a reference, normal peripheral T cells express full-length as well as the dominant negative LEF-1 isoform, whereas the colon cancer cell line, Colo 320, only expresses the full-length isoform (Figure 2D). Our findings concerning CLL B cells are of interest as it has been demonstrated in colon cancer that aberrant expression of full-length LEF-1 is Wnt signaling dependent.21

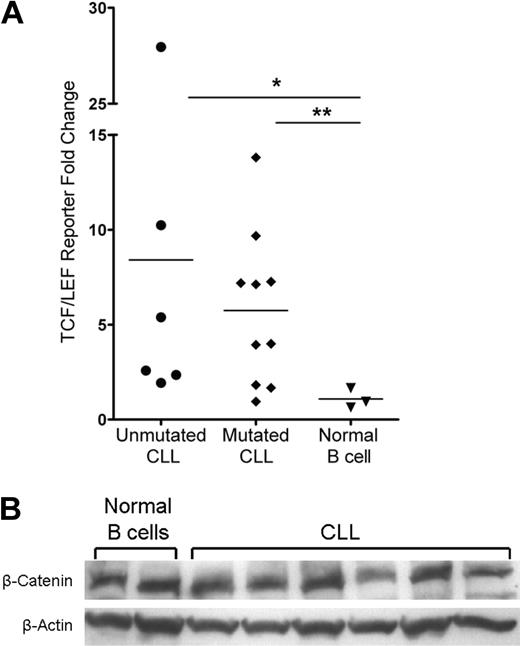

Wnt pathway activation in CLL cells and not normal B cells

Members of the TCF/LEF transcription factor family and β-catenin mediate Wnt target gene transcription in the nucleus, which is the culmination of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway. The basal activity of this pathway in normal peripheral B cells is unknown and is an important reference for aberrant activity detected in CLL. To assess the activity of the Wnt pathway in CLL and normal peripheral B cells, we used the TCF/LEF dual luciferase reporter assay system. Using this assay, we found that the majority of patients in the mutated and unmutated immunoglobulin expressing CLL prognostic groups had evidence of Wnt pathway activation (Figure 3A). Despite variation, the Wnt pathway was activated in CLL B cells with an average of more than 8-fold and 5-fold increases in the positive reporter samples observed in unmutated (n = 6, P = .024) and mutated (n = 10, P = .014) CLL samples, respectively (Figure 3A). By contrast, the Wnt pathway was dormant in 3 normal mature B-cell samples, which displayed no fold increase in the positive reporter samples (Figure 3A). These data demonstrate functional activation of the Wnt pathway in CLL and importantly a lack of activity in normal B-cell samples, which identifies leukemic CLL B-cell Wnt activity as indeed aberrant.

Activation of the Wnt pathway in CLL cells and not in normal mature B cells. (A) TCF/LEF dual luciferase reporter assay relative fold change of positive reporter samples from 6 unmutated CLL samples, 10 mutated CLL samples, and 3 normal B-cell samples. *P = .024. **P = .014. Horizontal lines indicate the mean of the group. (B) Western blot analysis of β-catenin in 6 CLL and 2 normal B-cell samples. β-Actin shown as a loading control of samples.

Activation of the Wnt pathway in CLL cells and not in normal mature B cells. (A) TCF/LEF dual luciferase reporter assay relative fold change of positive reporter samples from 6 unmutated CLL samples, 10 mutated CLL samples, and 3 normal B-cell samples. *P = .024. **P = .014. Horizontal lines indicate the mean of the group. (B) Western blot analysis of β-catenin in 6 CLL and 2 normal B-cell samples. β-Actin shown as a loading control of samples.

There are several possible mechanisms for Wnt activation in CLL, including a ligand-dependent Wnt signal possibly dependent on autocrine signaling (eg, via Wnt3) or a ligand-independent mutation or deregulation that leads to constitutive activation. The latter mechanism could possibly result in a uniform up-regulation of β-catenin in every CLL cell. To interrogate these mechanisms, we evaluated β-catenin levels by intracytoplasmic flow cytometry (data not shown) and Western blot in CLL and normal B cells. Surprisingly, there was no increase in total β-catenin protein levels in CLL relative to normal B-cell samples (Figure 3B). These observations suggest that a mutation(s) does not result in constitutively higher levels of β-catenin in CLL cells as the explanation for Wnt activation.

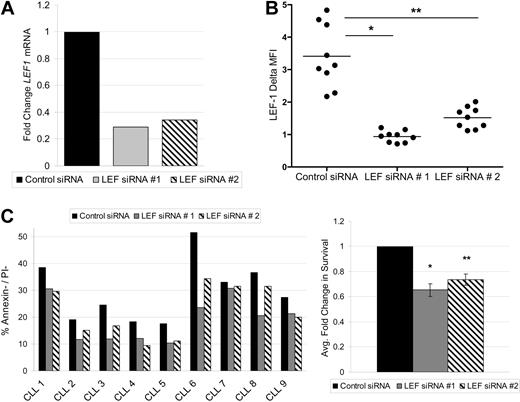

LEF-1 is a prosurvival factor in CLL cells

LEF-1 and the Wnt pathway are known to regulate survival in numerous cell types.22,23 To assess this possible function in CLL, we used siRNA to knock down expression of members of the Wnt pathway. We were successful at LEF-1 knockdown in 9 CLL samples. To protect against possible siRNA off-target effects, 2 separate siRNAs against LEF-1 were used. Each target siRNA caused a decrease in LEF1 mRNA levels at 24 hours relative to control siRNA treatment (Figure 4A). LEF-1 knockdown at the protein level was verified by flow cytometry, with LEF-1 siRNA treatment significantly decreasing the mean LEF-1 fluorescence intensity levels at 48 hours (data not shown) and 72 hours (Figure 4B). As expected, the process of nucleofection decreased the normally high survival seen in CLL cultures. Nonetheless, target siRNA treatment decreased CLL survival compared with control siRNA treatment at 72 hours (Figure 4C). When the cell survival data obtained from all 9 CLL patients tested were normalized to control siRNA treatment, LEF-1 knockdown resulted in an average decrease in survival of 35% (P = .0001) for target siRNA 1 and 27% (P = .0002) for target siRNA 2 (n = 9; Figure 4C). Collectively, these data demonstrate that the Wnt pathway is aberrantly activated in CLL and that LEF-1 specifically exerts a prosurvival effect in CLL B cells.

LEF-1 is a prosurvival factor in CLL cells. (A) Detection of LEF1 mRNA levels by quantitative PCR in B cells from a CLL patient 24 hours after siRNA treatment. (B) Intracellular flow cytometry measurements of LEF-1 expression with indicated change in mean fluorescence intensity (ΔMFI) 72 hours after siRNA treatment in 9 CLL samples. *P < .0001. **P < .0001. Horizontal lines indicate the mean of the group. (C) CLL percentage survival 72 hours after siRNA treatment in 9 samples (left panel), and the average fold change in survival normalized to control siRNA treatment (right panel). *P = .0001. **P = .0002. Error bars represent the SEM.

LEF-1 is a prosurvival factor in CLL cells. (A) Detection of LEF1 mRNA levels by quantitative PCR in B cells from a CLL patient 24 hours after siRNA treatment. (B) Intracellular flow cytometry measurements of LEF-1 expression with indicated change in mean fluorescence intensity (ΔMFI) 72 hours after siRNA treatment in 9 CLL samples. *P < .0001. **P < .0001. Horizontal lines indicate the mean of the group. (C) CLL percentage survival 72 hours after siRNA treatment in 9 samples (left panel), and the average fold change in survival normalized to control siRNA treatment (right panel). *P = .0001. **P = .0002. Error bars represent the SEM.

Cells of the CLL precursor state monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis express LEF-1

Because CLL expression of LEF-1 appears to increase leukemic cell survival, we hypothesized that LEF-1 may also play a role early in CLL leukemogenesis. To begin to investigate this possibility, we assayed for LEF-1 expression in the B cells from persons with the preleukemic state MBL. The current diagnostic cut-off for a diagnosis of MBL versus CLL is set at an absolute B-cell count of 5 × 109 cells/L. For our studies, we limited our experiments to MBL samples (n = 8) with an absolute B-cell count ranging from 0.7 to 2.4 × 109 cells/L (Table 1 legend), to be conservatively below the transition point between MBL and CLL. To investigate LEF-1 expression in MBL, we measured LEF-1 expression by flow cytometry in both the CD19+/CD5+ CLL phenotype B-cell population and the CD19+/CD5− normal B-cell population in each patient sample. LEF-1 was detected in the CD19+/CD5+ population of all 8 MBL samples studied. Three representative MBL samples are shown in Figure 5A, which clearly demonstrate that only the CD19+/CD5+ CLL phenotype subpopulation expressed LEF-1. We next evaluated the level of LEF-1 protein expression in the MBL populations and compared this with CLL LEF-1 expression levels. Interestingly, the change in mean fluorescence intensity (ΔMFI) forLEF-1 staining was significantly lower in MBL compared with CLL (n = 8 and 13, respectively; P = .002; Figure 5B). These data add support to our hypothesis that LEF-1 is deregulated in theMBL patients who have been shown by others and us to be at risk for progression to CLL.2,6

CD19+/CD5+ cells of the CLL precursor state MBL express LEF-1. (A) Three representative flow cytometric analyses of peripheral blood mononuclear cells from MBL patients stained with anti-CD19, CD5, and LEF-1 antibodies. Isotype control histogram is shaded gray; LEF-1 histogram is black. Data are representative of results obtained with 8 MBL patients. (B) The change in mean fluorescence intensity (ΔMFI) between isotype and anti–LEF-1 staining in 8 MBL and 13 CLL samples. *P = .002. Horizontal lines indicate the mean of the group.

CD19+/CD5+ cells of the CLL precursor state MBL express LEF-1. (A) Three representative flow cytometric analyses of peripheral blood mononuclear cells from MBL patients stained with anti-CD19, CD5, and LEF-1 antibodies. Isotype control histogram is shaded gray; LEF-1 histogram is black. Data are representative of results obtained with 8 MBL patients. (B) The change in mean fluorescence intensity (ΔMFI) between isotype and anti–LEF-1 staining in 8 MBL and 13 CLL samples. *P = .002. Horizontal lines indicate the mean of the group.

Discussion

In this study, we identified a pathogenic role for LEF-1 and the Wnt pathway in CLL and show evidence for its deregulation in the CLL precursor state, MBL. We also demonstrate that LEF-1 knockdown by siRNA specifically decreases CLL survival. Our results are consistent with 2 prior reports that found pharmacologic agents targeting the Wnt pathway in CLL decrease CLL cell survival.15,16 As small-molecule inhibitors often lack precise specificity, our use of LEF-1 siRNA provides definitive evidence of the important role that this molecule plays in the leukemic B cells. Our results using the TCF/LEF reporter assay add further support and mechanistic justification for Wnt-targeted therapy in CLL. In addition, in this study, we identified deregulation of Wnt pathway-associated genes in CLL B cells.

We also report here that the TCF4 (ITF-2) gene is overexpressed in CLL. This transcription factor is of great interest because it is a known downstream target of the Wnt pathway, is activated in human cancers with β-catenin defects, and it promotes neoplastic transformation.24 Another exciting discovery was CLL overexpression of the known Wnt target gene, CCND2, which regulates cellular proliferation. Overexpression of TCF4 and CCND2 provides further support to our hypothesis that the Wnt pathway is constitutively activated in CLL.

The results of our studies demonstrate, for the first time, that IGFBP4 protein is overexpressed in CLL B cells, an observation that is consistent with our prior demonstration that IGFBP4 mRNA is overexpressed in CLL.9 Of interest, IGFBP4 inhibits Wnt signaling through disruption of certain frizzled receptor and LRP6 coreceptor signaling.25 Hence, there is a complex deregulation of Wnt pathway-associated genes in CLL cells with both activators and inhibitors of the Wnt pathway being expressed.

Although our data showing WNT3 overexpression by CLL cells support previous findings, we did not observe overexpression of other Wnt ligands and frizzled receptor genes in CLL reported by other investigators.15 Thus, we identified 8 deregulated Wnt pathway-associated genes in CLL, but of these WNT3 was the only Wnt/Fzd gene up-regulated compared with controls. One possible explanation for this discrepancy is that we studied a larger cohort of CLL and control patients (n = 41 and n = 11, respectively) and identified universally deregulated Wnt-associated genes in CLL. Alternatively, because different methods of interrogating gene expression were used in each study (ie, microarray analysis vs quantitative PCR), it is possible that this factor contributed to the differences between the studies. Of note, we did observe that WNT 10a and FZD3 were indeed both up-regulated by greater than 1.5-fold over normal B cells; however, they only trended toward statistical significance. We can therefore conclude that there are similarities between previous studies and our analysis.

A primary observation emerging from our study is that the Wnt pathway transcription factor, LEF-1, is specifically expressed in CLL cells and not in normal mature B-cell subsets. Because CLL B cells have been shown to display an activated phenotype regardless of IGHV mutation status,8 it remained possible that CLL B-cell LEF-1 expression functioned simply as an activation marker. However, we clearly demonstrate that LEF-1 is not induced in normal B cells after polyclonal activation. It was similarly possible that LEF-1 is simply a marker of CD19+/CD5+ lineage B cells. Our analysis of cord blood B cells, a rich source of CD19+/CD5+ B cells, revealed their lack of LEF-1 expression. We also show, for the first time, that LEF-1 is expressed by human bone marrow B cells, which contain developing B-cell precursors. As CLL is clearly a post-GC B cell, it is probable that LEF-1 expression must have been reacquired during the leukemic transformation process. This theory was supported by the fact that the preleukemic clones of MBL patients were also found to express LEF-1, although at diminished levels compared with CLL. These data suggest that LEF-1 may be playing an important role during the initiation of CLL.

LEF-1 expression is a unifying characteristic of all CLL prognostic groups and is a prosurvival factor. Thus, it is interesting to speculate that LEF-1 is required for the initiation of CLL. Furthermore, LEF-1 potentially represents a category of developmentally important cancer genes that are required for cancer initiation but also lock in the differentiation status of the particular tumor cell. It is possible that CLL cells might lose the prosurvival function of LEF-1 if pushed into a further state of differentiation.

Functional activity of the Wnt pathway in primary CLL samples was identified through the TCF/LEF reporter assay system. Our evaluation of β-catenin levels in CLL suggest that the Wnt pathway is not uniformly activated by mutations that increase the constitutive level of β-catenin in CLL B cells. The precise signals, which activate the Wnt pathway in CLL B cells, remain to be elucidated and are the topic of ongoing investigation. One recently uncovered possibility is that CLL cells lack expression of a transcriptional repressor that associates with members of the TCF/LEF family in hematologic cells.26 This inhibitory loss could potentially disrupt the fine balance between positive and negative Wnt regulators in CLL.

LEF-1 and the Wnt pathway are known to regulate survival in numerous cell types and tumors. LEF-1 siRNA treatment decreased CLL survival at 72 hours in the majority of samples tested. There was one notable outlier, which lacked TCF/LEF reporter activity and had almost no decrease in cellular survival after LEF-1 knockdown. On further investigation, we found that this patient had a 17p deletion (which involves the p53 gene) and was previously treated, which raises the point that CLL clones with these characteristics may no longer rely on the Wnt pathway for survival. Nonetheless, our data have demonstrated the prosurvival function of LEF-1 and the Wnt pathway in the majority of CLL patients.

Interestingly, Notch and VEGF pathways have been found to interact with the Wnt pathway through transcriptional regulation and physical interactions with pathway members.23,27-30 These pathways have been recently studied and found to be active in CLL.31,32 Future studies are now needed to determine how CLL Wnt activity interacts with other oncogenic signaling pathways. In addition, apart from effects of Wnt signaling, LEF-1 has functions independent of β-catenin. Specifically, LEF-1 can function as an architectural context-dependent transcription factor and can interact with alternative coactivator factors, such as intracellular Notch and Aly.30,33 These functions will also be important to assess in future studies.

In conclusion, this study has added novel evidence regarding the aberrancy of LEF-1 and the Wnt pathway and its role in the survival of CLL leukemic B cells. This evidence implicates these factors as possible targets for future therapeutic strategies in patients with CLL. In addition, the studies presented here demonstrate that there is a probable deregulation of LEF-1 and the Wnt pathway in MBL, and hence these factors may have a role in CLL leukemogenesis.

Presented at the 50th and 51st annual meetings of the American Society of Hematology, San Francisco, CA, December 7, 2008, and New Orleans, LA, December 8, 2009.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Note added in proof:

While this manuscript was under review, a manuscript by Gandhirajan et al was published, similarly demonstrating that LEF-1 siRNA decreases CLL survival (Neoplasia. 2010;12(4):326-335).

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health (grants 1R01CA136591 and 5F31CA1432310).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: A.G. designed and performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; R.C.T. performed research and analyzed data; X.W. designed research and interpreted data; J.E.-P. performed statistical analysis; P.M.H., S.L.S., T.D.S., and N.E.K. designed research and enrolled patients; and D.F.J. designed research and wrote and approved the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Diane F. Jelinek, Mayo Clinic, Guggenheim 4, 200 First St SW, Rochester, MN 55905; e-mail: jelinek.diane@mayo.edu.

![Figure 1. Deregulation of Wnt pathway gene expression in CLL. (A) Detection of LEF1, WNT3, TCF4 [ITF-2], and CCND2 mRNA levels by quantitative PCR in leukemic or normal B cells from 8 CLL patients and 3 healthy donor samples, respectively. Transcript levels were normalized to 18s rRNA, and relative fold change was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method. *P < .05. Error bars represent SEM. (B) Detection of IGFBP-4 protein secretion into culture media by ELISA in B cells from 6 CLL patients and 3 healthy donor samples. The dashed line at 5 ng/mL indicates the ELISA threshold level of IGFBP-4 detection, and the horizontal lines indicate the mean of each group.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/116/16/10.1182_blood-2010-02-269878/4/m_zh89991058320001.jpeg?Expires=1765046429&Signature=WqyBUXIJiRJNl5NRuqyORVL7cOJ7f5jqjnY1B61GUEiLCHN6sD3zkgVR8OwI8AzeTVM50J-uHRX4tZSrgKElRehd-4PRhjDstt8ncb27uUHa2INHPodYV7edrfdv-qtyr~yBJ7g5zrdxrDythGDESf8qElWebLAqOmKzfXGQgGa36VzSyoSvxuVJHuB4BvQHN3-GybX8dpcQhFIwYl7W1vTMmOsYyqk75QHx6YgtrKEv-DuB7EbPdG0Tv93zDSkFeIZSt~7DcPi-FpdDU7Tt0Bt5nWr071ED9czDEfQw0MsZQ~jBLkaO3KaoqLxIqduixxzhs-K9sGuOs2OjdOkYjA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal