Abstract

The identification of molecules responsible for apoptotic cell (AC) uptake by dendritic cells (DCs) and induction of T-cell immunity against AC-associated antigens is a challenge in immunology. DCs differentiated in the presence of interferon-α (IFN-α–conditioned DCs) exhibit a marked phagocytic activity and a special attitude in inducing CD8+ T-cell response. In this study, we found marked overexpression of the scavenger receptor oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor 1 (LOX-1) in IFN-α–conditioned DCs, which was associated with increased levels of genes belonging to immune response families and high competence in inducing T-cell immunity against antigens derived from allogeneic apoptotic lymphocytes. In particular, the capture of ACs by IFN-α DCs led to a substantial subcellular rearrangement of major histocompatibility complex class I and class II molecules, along with enhanced cross-priming of autologous CD8+ T cells and CD4+ T-cell activation. Remarkably, AC uptake, CD8+ T-cell cross-priming, and, to a lesser extent, priming of CD4+ T lymphocytes were inhibited by a neutralizing antibody to the scavenger receptor LOX-1 protein. These results unravel a novel LOX-1–dependent pathway by which IFN-α can, under both physiologic and pathologic conditions, render DCs fully competent for presenting AC-associated antigens for cross-priming CD8+ effector T cells, concomitantly with CD4+ T helper cell activation.

Introduction

Dendritic cells (DCs) are potent antigen-presenting cells that play a crucial role in the regulation of the immune response.1 One typical feature of DCs is their capability to take up complex structures and present defined antigens to T-cell subsets. Notably, DCs are capable of efficiently taking up particulate materials from dying cells, including apoptotic cells (ACs), and this attitude is lost during DC maturation.2-4 In the absence of danger signals, AC uptake by DCs tends to lead to tolerance rather than immunity. Noteworthy, uptake of ACs by DCs and the mechanisms allowing these cells to selectively present AC-associated antigens to CD8+ effector T cells (cross-presentation) or to CD4+ T helper cells represent biologically relevant processes playing crucial roles in the host responses for inducing either immunity or tolerance in pathologic and physiologic conditions.5-7 Thus, the identification of the naturally occurring DC signals and mechanisms rendering these cells competent in inducing immunity against AC-associated antigens represents a central challenge for the progress in immunology.

The authors of recent studies3,8,9 have shown that the recognition and ingestion of ACs by DCs involve at least 3 different classes of molecules: “eat-me” molecules expressed by ACs, soluble bridging molecules (eg, pentraxins), and endocytic receptors expressed by phagocytes such as the scavenger receptors (SRs) CD91, CD36, and oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor 1 (LOX-1). Originally identified as a lectin-like receptor binding internalizing oxidized low-density lipoprotein on endothelial cells,10,11 LOX-1 has been associated with various functions related to immunity, including leukocyte recruitment.12 This receptor interacts with ACs as well as other ligands including platelets, bacteria, and heat shock proteins (Hsp).13 Recently, it has been reported that LOX-1 is expressed on certain DC types and can be involved in antigen cross-presentation.14 Because of its high affinity for Hsp70, LOX-1 can mediate Hsp70-peptide complex uptake by DCs that, after antigen processing, stimulate CD8+ T-cytotoxic T cells.14,15 Thus, the clarification of the mechanisms controlling LOX-1 function in DCs can provide important insights into the understanding of the modulation of immune responses in physiologic and pathologic conditions.

The current procedure for the in vitro generation of DCs is on the basis of the exposure of granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF)–treated monocytes to diverse cytokines, including interleukin-4 (IL-4) and interferon-α (IFN-α). Although IL-4 is the typical cytokine inducing the phenotype of immature DCs, IFN-α induces a one-step differentiation of monocytes into highly activated and partially mature DCs (hereafter IFN-α–conditioned DCs or IFN-α DCs) retaining a marked phagocytic activity and exhibiting a special attitude in inducing CD8+ T cells against both viral and tumor antigens.16-18 Notably, an ensemble of studies19-22 performed by several laboratories, including ours, on the phenotype and functions of IFN-α DCs have led to the concept that these cells can resemble to naturally occurring DCs, rapidly generated from monocytes in response to danger signals, including infection. In fact, IFN-α are cytokines rapidly produced at high levels in response to viral infections, which can play a critical role in linking innate and adaptive immunity.23,24

In this study, we have characterized the gene expression profiles of IFN-α–conditioned DCs and correlated the expression of a defined set of genes of the immune response and innate immunity to the specific ability of these cells to take up apoptotic allogeneic lymphocytes (APO-allo-PBLs) and to induce cross-priming of autologous CD8+ T cells and CD4+ T-cell activation. We found that LOX-1 protein is up-regulated in IFN-α DCs and that this receptor mediates most of the peculiar features of these cells in presenting AC-associated antigens. Overall these results unravel a novel natural IFN-α–mediated pathway in DCs by which LOX-1 mediates AC uptake and subsequent induction of T-cell immunity.

Methods

Cell separation and culture

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were obtained from the heparinized blood of healthy donors by Ficoll density gradient centrifugation (Seromed). Monocytes were isolated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells by column magnetic immunoselection (MACS Cell Isolation Kits; Miltenyi Biotec). Positively selected CD14+ monocytes were plated at the concentration of 2 × 106cells/mL in RPMI 1640 (GIBCO) supplemented with 10% lipopolysaccharide (LPS)–free fetal calf serum. Cultures were maintained for 3 days with 500 U/mL GM-CSF alone or in combination with either 250 U/mL IL-4 (R&D Systems) or natural IFN-α (Alfaferone; AlfaWasserman) at concentration of 10 000 U/mL. After 3 days of culture, nonadherent and loosely adherent cells were collected and used for subsequent analysis. In some experiments, DCs were also treated for 24 hours with LPS (1 μg/mL) to induce DC maturation. In Western blot and CLSM experiments, IFN-α DCs and IL-4 DCs were treated overnight with tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α; 50 ng/mL; Peprotech). All reagents were tested for the absence of detectable levels of LPS by the Limulus Amebocyte lysate assay (Bio-Whittaker). Human CD8+ and CD4+ T cells were isolated by positive magnetic immunoselection (MACS Cell Isolation Kits; Miltenyi Biotec).

RNA preparation and microarray hybridization

After 3 days of culture, nonadherent cells were harvested. Total RNA was extracted, purified, and labeled for hybridization to HG U133A GeneChip oligonucleotide arrays (Affymetrix) following the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, total RNA from GM-CSF–treated monocytes, IFN-α DCs, and IL-4 DCs was immediately isolated with the RNAeasy kit (QIAGEN) and converted to double-stranded cDNA with a T7-polyT primer and the SuperScript Choice System kit (Invitrogen). Biotinylated cRNA was synthesized by in vitro transcription by use of the Bio Array High Yield RNA Transcript Labeling System (ENZO kit), purified, and fragmented by metal-induced hydrolysis. Fifteen micrograms of fragmented cRNA were hybridized overnight to GeneChip HG-U133A arrays (Affymetrix) containing more than 22 000 probe sets and the expression levels of 18 400 transcripts and variants, including 14 500 well-characterized human genes, were analyzed on an Affymetrix scanner.

Data filtering and normalization, clustering, and statistical analysis

The dataset is represented by 4 control arrays (GM-CSF) and 8 test arrays (4 for IFN-α treatment and 4 for IL-4 treatment). The raw expression data have been normalized all together by use of the gcrma routine25 included in the Bioconductor (http://www.bioconductor.org) package.26 Microarray data were deposited in the ArrayExpress database (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress) with the following MIAMExpress accession number: E-MEXP-2000. Further information is available from the authors upon request.

Gene filtering: first step.

Following the standard Affymetrix procedure, the Presence/Absence/Marginality calls were calculated for the whole dataset. A condition for the genes of at least 1 Presence in the 12 arrays was imposed, and the distribution of intensities of the remaining set of totally absent genes was calculated. The intensity value that covers the 95% of the cumulative distribution was chosen as the background intensity lower threshold.

Gene filtering: second step.

The significance analysis of microarrays (SAM) algorithm27 was used to select those genes significantly modulated by the 2 treatments (IFN-α and IL-4) with respect to the common control (GM-CSF). The significance analysis was performed by use of the 2-class unpaired approach: IFN-α in comparison with GM-CSF (Delta = 1.4 fold change, false discovery rate 0.02) and IL-4 in comparison with GM-CSF (Delta = 2.0 fold change, false discovery rate 0.03). Two lists of genes were generated and analyzed by the EASE algorithm28 to determine which of the gene families, according to the Gene Ontology classification, were overexpressed in each of the 2 groups (http://david.niaid.nih.gov/david/ease.htm). The 2 lists of significant genes, together with their eventual overlaps, were merged into a global list of 786 significant genes. To find the differences between the 2 treatments, the filtered dataset of 786 significant genes was prepared in terms of treatment/control log ratios, crossing all the samples. In such way, 32 different log ratios for each of the 786 genes were obtained. Once again, the SAM algorithm was used by the 2-class unpaired approach to search those genes demonstrating significant differences in their modulation in both treatments. The discriminant genes obtained from SAM analysis were analyzed by EASE algorithm.

Hsp70 binding

Hsp70-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) was obtained by conjugation of human recombinant Hsp70 (Sigma-Aldrich) with FITC by use of the FluoroTag FITC-conjugation kit (Sigma-Aldrich), according to the manufacturer's instructions. IFN-α DCs and IL-4 DCs (2 × 105 cells) were incubated with Hsp70-FITC at 4°C for 20 minutes in phosphate-buffered saline and then washed in the same buffer. The Hsp70 binding capability was evaluated by analysis of the fluorescence emission with a FACSort flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). For the neutralizing experiments, cells were preincubated with anti–LOX-1 monoclonal antibody (mAb; clone 23C11; Hycult biotechnology) or an isotype control mAb (mouse immunoglobulin G1 [IgG1]) for 20 minutes at 4°C and subsequently incubated with Hsp70-FITC.

LOX-1 expression analysis

The expression of LOX-1 mRNA was evaluated by reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis. In brief, after extraction by RNeasy kit (QIAGEN), 1 μg of RNA from DCs was reverse-transcribed and used to analyze transcript expression by amplifying with specific primer pair for LOX-1 (5′-TTACTCTCCATGGTGGTGGTGCC-3′ and 5′-AGCTTCTTCTGCTTGTTGCC-3′). The samples were amplified for 32 cycles with an annealing temperature of 62°C. β-actin primers were used to normalize the levels of human RNA in all the samples.

Western blot analysis

Treated and untreated DCs were lysed as described.29 After centrifugation (16 000g, 15 minutes), the supernatant fractions were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in 12% acrylamide gels and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Amersham). Blots were probed with rat anti–human LOX-1 IgG.29 Immunoreactive bands were detected with donkey anti–rat horseradish peroxidase (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) and visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Sigma-Aldrich). Protein level was monitored by probing the same blots with anti–α-tubulin IgG.

Phagocytosis of ACs

Peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs) were dyed red with PKH26-GL (Sigma-Aldrich) and induced to undergo apoptosis by γ-irradiation (10 000 rad) for 24 hours. The labeled ACs were harvested, washed, and finally incubated for 24 hours at 4°C or 37°C with IFN-α DCs or IL-4 DCs at a 1:7 ratio (DC/AC). After coculture, DCs were stained with anti–HLA-ABC-FITC mAb (Becton Dickinson), and phagocytosis was detected by fluorescence-activated cell-sorting analysis enumerating double-positive HLA-ABC-FITC+/AC-PKH26-PE+ cells. Phagocytosis assay was performed in the presence or absence of the neutralizing anti–LOX-1 mAb (50 μg/mL; clone 23C11; Hycult biotechnology). In some experiments, phagocytosis analysis was performed after 3 hours of IFN-α DCs/AC coculture. Apoptosis of irradiated allogeneic PBLs was confirmed by the use of the ApoAlert annexin V–FITC Apoptosis kit (Clontech). Cells were stained with annexin V–FITC and propidium iodide and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Mixed lymphocyte reaction

Decreasing numbers of DCs were added to 105 allogeneic monocyte-depleted PBLs/well. After 5 days, cells were pulsed with 1 μCi of (methyl-3H)thymidine (Amersham) per well for 18 hours, harvested, and counted for thymidine uptake quantification.

Assay of DC presentation of alloantigens from ACs to autologous CD8+ or CD4+ T cells

IFN-α DCs and IL-4 DCs were cocultured with irradiated (10 000 rad) allogeneic PBLs (APO-allo-PBLs) for 24 hours in the presence or absence of anti–LOX-1 mAb (clone 23C11; Hycult biotechnology) or isotype control IgG1 and then cocultured with autologous purified CD8+ or CD4+ T cells at different stimulator/responder ratios. After a 6-day coculture, the DC capability to cross-present apoptotic body-derived antigens was evaluated by (methyl-3H) thymidine incorporation. As specific control, CD8+ and CD4+ T cells also were primed with AC-loaded DCs in the presence of anti–HLA-ABC mAb or anti-CD4 mAb, respectively. Death of irradiated allogeneic PBLs was confirmed by use of the ApoAlert kit (Clontech Lab), as described previously.

Confocal microscopy

DCs were seeded on cover glasses coated with poly-L-lysine (10 μg/mL, 20 minutes, room temperature; Sigma-Aldrich) and allowed to attach for 15 minutes at 37°C. After washing with phosphate-buffered saline, cells were incubated with FITC-conjugated anti–HLA-ABC, anti–HLA-DR mAbs (BD Pharmingen), or with polyclonal anti–LOX-1 Ab29 at 4°C for 30 minutes. LOX-1 expression was revealed by a Rhodamine Red-conjugated donkey anti–rat IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). To analyze fixed samples, cells were fixed by cold methanol (10 minutes, −20°C) and then stained at 37°C with FITC-conjugated anti–HLA-ABC and anti–HLA-DR mAbs or with anti-lysosome–associated membrane protein-2 (LAMP-2) mAb (BD Pharmingen), whose binding was revealed by the use of Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated secondary Ab (Molecular Probes). Isotype control antibodies were used in all confocal microscopy experiments to confirm the specificity of antibody staining. The cover glasses were mounted on the microscope slide with Vectashield antifade mounting medium containing 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Vector Laboratories). CLSM observations were performed with a Leica TCS SP2 AOBS apparatus and image acquisition and processing were carried out with the Leica Confocal Software (Leica Lasertechnik) and Adobe Photoshop software programs (Adobe Systems Inc).

Statistical analysis

P values were calculated by 2-tailed t test (n > 3). Statistical significance of the differences in AC uptake was determined by Mann-Whitney/Wilcoxon U test with SPSS version 14.0 (SPSS Inc).

Results

Transcriptome changes induced by IFN-α shape pathways of the immune response in DCs

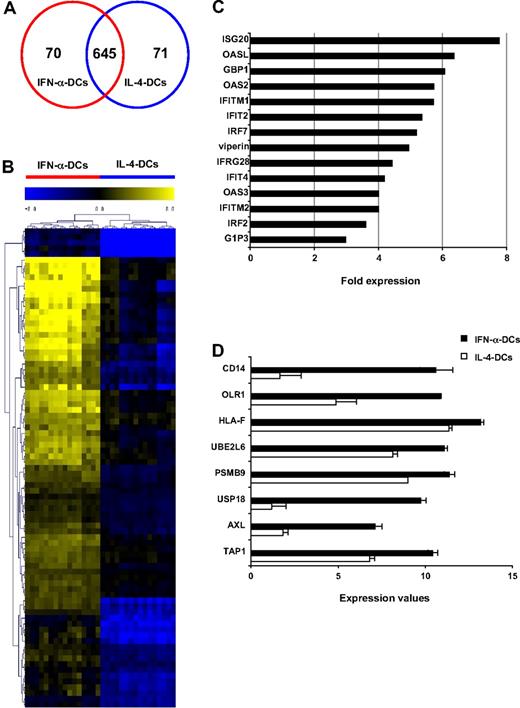

We performed transcription analysis of IFN-α DCs as well as IL-4 DCs with respect to monocytes differentiated in the presence of GM-CSF alone. We found that 786 genes were significantly modulated after IFN-α or IL-4 treatment with respect to GM-CSF alone. In particular, 70 and 71 genes exhibited significant differences in their modulation after IFN-α and IL-4-treatments, respectively, whereas 645 genes were not differentially modulated by the 2 treatments (Figure 1A). We next performed a Gene Ontology categories analysis (http://david.niaid.nih.gov/david/ease.htm), which showed extensive differences in terms of overexpressed gene families modulated by IFN-α or IL-4 treatment with respect to GM-CSF alone. IFN-α–driven differentiation of monocytes into DCs was characterized by up-regulation of genes implicated in immunologic pathways, such as innate immune response, inflammatory response, chemotaxis, signal transduction, cytokine and chemokine activity, antigen processing, and presentation. On the contrary, the IL-4 treatment mainly induced genes related to metabolic pathways (Table 1). Hierarchical cluster analysis of genes specifically modulated by IFN-α treatment confirmed the strong differences in gene profiles between the 2 DC populations (Figure 1B). As expected, IFN-α DCs showed a strong induction of the best-characterized IFN-α–inducible genes (2′-5′-OAS, IFIT2, IFIT4, ISG20, IFITM2, cig5, IFI27) and of transcription factor genes belonging to the IRF family (IRF2 and IRF7; Figure 1C), along with up-regulation of mRNA encoding proteins involved in inflammatory response (S100A8, S100A9, MyDD88), chemotaxis (CCL8, CX3CR1, CXCL10/IP10, CXCL3, CXCL2), apoptosis, and cytotoxicity (Fas, TRAIL, caspase 1; data are available on the ArrayExpress database; see “Data filtering and normalization, clustering, and statistical analysis”).

Effect of IFN-α on the gene expression profile of monocyte-derived DCs. (A) Venn diagram showing the numbers of differentially expressed genes in IFN-α DCs and IL-4 DCs with respect to monocytes treated with GM-CSF alone. (B) Signature clusters of the 70 differentially expressed genes in IFN-α DCs compared with the same genes in IL-4 DCs. Yellow and blue colors denote increased and decreased gene expression, respectively, compared with values of common control. (C) Fold increase in the expression of selected up-modulated genes in IFN-α DCs versus control, expressed as CrossLogRatio values. (D) Expression values of selected genes linked to phagocytosis/endocytosis and Ag-processing pathways in IFN-α DCs and IL-4 DCs, expressed as log intensities (error bars indicate SD).

Effect of IFN-α on the gene expression profile of monocyte-derived DCs. (A) Venn diagram showing the numbers of differentially expressed genes in IFN-α DCs and IL-4 DCs with respect to monocytes treated with GM-CSF alone. (B) Signature clusters of the 70 differentially expressed genes in IFN-α DCs compared with the same genes in IL-4 DCs. Yellow and blue colors denote increased and decreased gene expression, respectively, compared with values of common control. (C) Fold increase in the expression of selected up-modulated genes in IFN-α DCs versus control, expressed as CrossLogRatio values. (D) Expression values of selected genes linked to phagocytosis/endocytosis and Ag-processing pathways in IFN-α DCs and IL-4 DCs, expressed as log intensities (error bars indicate SD).

Significantly enriched gene ontology terms for genes up-regulated in IFN-α and IL-4 DCs

| Treatment/GO system and GO category/terms . | Benjamini adjustment factor* . |

|---|---|

| IFN-α biologic processes | |

| Immune response | 2.4e-019 |

| Defense response | 4e-019 |

| Response to external stimuli | 4.7e-016 |

| Organismal physiologic process | 5.3e-014 |

| Response to pathogen/parasite | 1.6e-007 |

| Inflammatory response | 5.6e-006 |

| Innate immune response | 7.2e-006 |

| Response to stress | 1.7e-004 |

| Chemotaxis | 2.5e-003 |

| Physiologic process | 3e-002 |

| Apoptosis | 4.7e-002 |

| Antigen presentation | 1.3e-001 |

| Antigen processing | 1.4e-001 |

| IFN-α molecular functions | |

| Signal transducer activity | 3e-002 |

| Cytokine activity | 3e-002 |

| Chemokine activity | 4.7e-002 |

| Transmembrane receptor activity | 1e-001 |

| Oxidoreductase activity | 7.9e-003 |

| RNA binding | 1e + 000 |

| Catalytic activity | 1e + 000 |

| IL-4 molecular function | |

| Oxidoreductase activity | 7.9e-003 |

| RNA binding | 1e + 000 |

| Catalytic activity | 1e + 000 |

| IL-4 biologic processes | |

| Lipid metabolism | 3.9e-002 |

| Fatty acid metabolism | 1.6e-001 |

| Biosynthesis | 1e + 000 |

| Macromolecule biosynthesis | 1e + 000 |

| Carboxylic acid metabolism | 1e + 000 |

| Organic acid metabolism | 1e + 000 |

| IL-4 cellular components | |

| Membrane | 1e + 000 |

| Treatment/GO system and GO category/terms . | Benjamini adjustment factor* . |

|---|---|

| IFN-α biologic processes | |

| Immune response | 2.4e-019 |

| Defense response | 4e-019 |

| Response to external stimuli | 4.7e-016 |

| Organismal physiologic process | 5.3e-014 |

| Response to pathogen/parasite | 1.6e-007 |

| Inflammatory response | 5.6e-006 |

| Innate immune response | 7.2e-006 |

| Response to stress | 1.7e-004 |

| Chemotaxis | 2.5e-003 |

| Physiologic process | 3e-002 |

| Apoptosis | 4.7e-002 |

| Antigen presentation | 1.3e-001 |

| Antigen processing | 1.4e-001 |

| IFN-α molecular functions | |

| Signal transducer activity | 3e-002 |

| Cytokine activity | 3e-002 |

| Chemokine activity | 4.7e-002 |

| Transmembrane receptor activity | 1e-001 |

| Oxidoreductase activity | 7.9e-003 |

| RNA binding | 1e + 000 |

| Catalytic activity | 1e + 000 |

| IL-4 molecular function | |

| Oxidoreductase activity | 7.9e-003 |

| RNA binding | 1e + 000 |

| Catalytic activity | 1e + 000 |

| IL-4 biologic processes | |

| Lipid metabolism | 3.9e-002 |

| Fatty acid metabolism | 1.6e-001 |

| Biosynthesis | 1e + 000 |

| Macromolecule biosynthesis | 1e + 000 |

| Carboxylic acid metabolism | 1e + 000 |

| Organic acid metabolism | 1e + 000 |

| IL-4 cellular components | |

| Membrane | 1e + 000 |

IFN-α treatment induces overexpression of gene families linked to immunologic pathways, compared with IL-4 treatment enhancing metabolic pathways. IFN-α–induced gene categories show very high statistical significance in comparison with those modulated by IL-4 treatment.

DC indicates dendritic cell; GO, gene ontology; IFN-α, interferon-α; and IL-4, interleukin-4.

Benjamini adjustment factor was obtained by Benjamini-Hochberg correction of the statistical significance of effects estimated with multiple comparisons by controlling false discovery rate (FDR).

Altogether these results indicate that IFN-α DCs are characterized by gene expression profiles typical of highly active DCs. Interestingly, the hierarchical cluster analysis of the 70 genes modulated in IFN-α DCs further revealed that the expression of certain genes linked to phagocytosis/endocytosis and antigen-processing pathways was specifically up-modulated in these cells with respect to IL-4 DCs (Figure 1D). Consistently with our previous data, IFN-α DCs expressed the transcript of the monocytic marker CD14, which also was detected on the cell surface of IFN-α DCs by flow cytometric analysis (data not shown).16 Of note, the OLR1 gene, which codes the human lectin-like LOX-1, was significantly up-modulated after treatment with IFN-α with respect to IL-4. Of interest, IFN-α DCs also demonstrated an increased expression of genes coding major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I, TAP1, and LAMP-2 molecules. In the subsequent studies, we focused our attention on LOX-1 and its specific role in mediating some functional characteristics typical of IFN-α DCs.

Expression and function of LOX-1 in IFN-α–conditioned DCs

We first confirmed the preferential expression of LOX-1 in IFN-α DCs with respect to IL-4 DCs by reverse transcription PCR analysis. High levels of LOX-1 were detected in IFN-α DCs, whereas the expression of this molecule was completely lost after LPS treatment, a stimulus known to ultimate DC maturation. Conversely, LOX-1 was only barely detectable in IL-4 DCs as well as in mature IL-4 DCs (Figure 2A). We further investigated the expression of LOX-1 by measuring the protein levels by means of 2 different approaches. Western blot analysis showed that endogenous LOX-1 protein was clearly detected in extracts derived from IFN-α DCs, and its expression was enhanced after TNF-α treatment, a well-known inducer of LOX-1.30 On the contrary, LOX-1 was detected only after treatment with TNF-α in IL-4 DCs (Figure 2B). Confocal laser-scanning microscopy (CLSM) further confirmed a clear-cut expression of LOX-1 on the surface membrane of IFN-α DCs with respect to the barely detectable levels observed in IL-4 DCs. In addition, TNF-α treatment stimulated a strong up-modulation of LOX-1 at the membrane level of IFN-α DCs (Figure 2C).

Selective LOX-1 expression in IFN-α DCs. (A) Semiquantitative PCR analysis of LOX-1 expression in IFN-α DCs and IL-4 DCs at basal levels or after LPS stimulation. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments with DCs derived from different donors. (B) LOX-1 protein expression in IFN-α DCs and IL-4 DCs cultured with or without TNF-α. All blots were probed with rat anti–human LOX-1 antiserum. LOX-1 protein appears as 3 different glycosylated forms in acrylamide gel electrophoresis. Data are representative of 4 independent experiments. (C) CLSM analysis showing the expression of LOX-1 on the surface membrane of DCs. Nuclear staining by DAPI (blue). Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. Scale bars, 10 μm.

Selective LOX-1 expression in IFN-α DCs. (A) Semiquantitative PCR analysis of LOX-1 expression in IFN-α DCs and IL-4 DCs at basal levels or after LPS stimulation. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments with DCs derived from different donors. (B) LOX-1 protein expression in IFN-α DCs and IL-4 DCs cultured with or without TNF-α. All blots were probed with rat anti–human LOX-1 antiserum. LOX-1 protein appears as 3 different glycosylated forms in acrylamide gel electrophoresis. Data are representative of 4 independent experiments. (C) CLSM analysis showing the expression of LOX-1 on the surface membrane of DCs. Nuclear staining by DAPI (blue). Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. Scale bars, 10 μm.

We then evaluated the binding of Hsp70 to both DC types and the resulting functional activation of IFN-α DCs after Hsp70 binding. Both IFN-α DC and IL-4 DCs were able to bind FITC-labeled recombinant human Hsp70, but only in IFN-α DCs this binding was prevented by the use of a neutralizing anti–LOX-1 antibody, with a rate of inhibition of approximately 50% (Figure 3A). Moreover, IFN-α DCs exposed to exogenous Hsp70 exhibited, with respect to untreated IFN-α DCs, a greater capacity to stimulate the proliferation of allogeneic T lymphocytes with respect to untreated IFN-α DCs, whose proliferation was inhibited by anti–LOX-1 antibody (Figure 3B).

Hsp70-binding activity of LOX-1 in IFN-α DCs. (A) IFN-α DCs and IL-4 DCs were incubated with a neutralizing anti–LOX-1 mAb (blue lines) or isotype control anti-IgG1 mAb (red lines). After 20 minutes, Hsp70-FITC was added to the cultures and revealed by fluorescence-activated cell-sorting analysis. Black and yellow lines represent, respectively, Hsp70-treated DCs and DCs cultured alone. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments. (B) Allostimulatory capacity of IFN-α DCs cultured in the presence or absence of Hsp70. IFN-α DCs were also preincubated with anti–LOX-1 or isotype control IgG1 mAbs. The proliferation of allogeneic T cells cocultured with DCs at the indicated ratio was determined by [3H]thymidine incorporation. The results represent the mean ± SD of data obtained from 3 different experiments.

Hsp70-binding activity of LOX-1 in IFN-α DCs. (A) IFN-α DCs and IL-4 DCs were incubated with a neutralizing anti–LOX-1 mAb (blue lines) or isotype control anti-IgG1 mAb (red lines). After 20 minutes, Hsp70-FITC was added to the cultures and revealed by fluorescence-activated cell-sorting analysis. Black and yellow lines represent, respectively, Hsp70-treated DCs and DCs cultured alone. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments. (B) Allostimulatory capacity of IFN-α DCs cultured in the presence or absence of Hsp70. IFN-α DCs were also preincubated with anti–LOX-1 or isotype control IgG1 mAbs. The proliferation of allogeneic T cells cocultured with DCs at the indicated ratio was determined by [3H]thymidine incorporation. The results represent the mean ± SD of data obtained from 3 different experiments.

Because LOX-1 has been implicated in the recognition of ACs,3,9 we asked whether IFN-α DCs could use LOX-1 as a receptor for the AC phagocytosis. First, we observed that IFN-α DCs exhibited considerable phagocytic activity for PHK26-stained apoptotic gamma-irradiated allogeneic PBLs (APO-allo-PBLs) as revealed by the greater percentage of AC-loaded IFN-α DCs with respect to AC-loaded IL-4 DCs (29.7% vs 20.3%). Interestingly, when DCs were treated with anti–LOX-1 antibody before the coculture with APO-allo-PBLs, only the IFN-α DCs showed a significant reduction in the uptake of ACs (Figure 4A). We then performed a set of CLSM analyses to better characterize AC phagocytosis by IFN-α DCs. Of note, high levels of internalized ACs could be revealed in IFN-α DCs, and the internalization of ACs was strongly inhibited by pretreatment of IFN-α DCs with anti–LOX-1 antibody (Figure 4B).

IFN-α DCs are endowed with high capability to capture ACs via LOX-1 receptor. (A-B) DCs were cocultured with PHK26-PE–labeled AC, in the presence or in absence of anti–LOX-1 mAb. Phagocytosis was evaluated by flow cytometry (A) and by CLSM (B, scale bars = 10 μm). Bars in panel A represent the mean ± SD percentage of AC-loaded DCs as double-positive cells; **P = .018 (n = 7); *P = .066 (n = 4).

IFN-α DCs are endowed with high capability to capture ACs via LOX-1 receptor. (A-B) DCs were cocultured with PHK26-PE–labeled AC, in the presence or in absence of anti–LOX-1 mAb. Phagocytosis was evaluated by flow cytometry (A) and by CLSM (B, scale bars = 10 μm). Bars in panel A represent the mean ± SD percentage of AC-loaded DCs as double-positive cells; **P = .018 (n = 7); *P = .066 (n = 4).

LOX-1–dependent capability of IFN-α–conditioned DCs in presenting AC-associated antigens to autologous CD8+ and CD4+ T lymphocytes

Although DCs have been reported to be capable of taking up ACs and induce under special conditions T-cell immunity, the mechanisms and molecules involved in these processes remained unknown. As shown in Figure 5A, IFN-α DCs loaded with APO-allo-PBLs exhibited a surprisingly high capacity to stimulate autologous CD8+ T cells compared with AC-loaded IL-4 DCs. Of interest, when IFN-α DCs were preincubated with the neutralizing anti–LOX-1 antibody, their capacity to stimulate CD8+ T cells was significantly reduced. The coculture of CD8+ T cells with AC-loaded IFN-α DCs in the presence of an anti–MHC class I antibody resulted in a total inhibition of the cross-priming of CD8+ T cells. In parallel, we performed autologous stimulation of CD4+ T cells with APO-allo-PBL–loaded DCs and found a markedly greater capacity of IFN-α DCs to stimulate the proliferation of CD4+ T helper cells compared with IL-4 DCs (Figure 5B). Of interest, the neutralization of LOX-1 receptor by a specific antibody significantly reduced this proliferative response at levels comparable with those obtained by blocking the CD4+ molecules (Figure 5B left). In contrast, IL-4 DCs loaded with APO-allo-PBLs exhibited a low capacity in stimulating autologous CD4+ T cells, which was not affected by anti–LOX-1 antibody (Figure 5B right).

AC-loaded IFN-α DCs are powerful activators of both autologous CD8+ and CD4+ T cells. CD8+ T cells (A) and CD4+ T cells (B) were primed with autologous IFN-α DCs or IL-4 DCs, previously pulsed with allogeneic ACs. Some cultures were preincubated with anti–LOX-1 mAb before AC phagocytosis. Data represent the mean cpm of triplicate wells ± SD of one of 4 independent experiments showing similar results. Asterisks refer to given P values.

AC-loaded IFN-α DCs are powerful activators of both autologous CD8+ and CD4+ T cells. CD8+ T cells (A) and CD4+ T cells (B) were primed with autologous IFN-α DCs or IL-4 DCs, previously pulsed with allogeneic ACs. Some cultures were preincubated with anti–LOX-1 mAb before AC phagocytosis. Data represent the mean cpm of triplicate wells ± SD of one of 4 independent experiments showing similar results. Asterisks refer to given P values.

MHC class I and MHC class II rearrangement and colocalization with ACs after AC uptake by IFN-α–conditioned DCs

To investigate the intracellular pathways related to the peculiar ability of IFN-α DCs in taking up ACs via LOX-1 and in processing AC-associated antigens in both a MHC class I– and MHC class II–restricted manner, we first monitored the expression and the distribution of MHC class I and MHC class II molecules as well as of ACs in both DC populations by means of CLSM at different coculture times. Untreated IFN-α DCs showed a high expression of MHC class I molecules; upon capture of ACs, MHC class I molecules and APO-allo-PBLs clearly colocalized in IFN-α DCs (Figure 6A). Notably, when IFN-α DCs were exposed to anti–LOX-1 antibody before coculture with APO-allo-PBLs, the AC-MHC class I colocalization was partially reduced as result of a significantly reduced uptake of APO-allo-PBLs. On the contrary, IL-4 DCs showed a lower expression of MHC class I molecules with respect to IFN-α DCs, and no MHC class I/AC colocalization was detected (Figure 7A).

MHC-I and MHC-II molecules rearrange and colocalize with ACs in IFN-α DCs upon AC uptake. CLSM analysis (central optical sections) of IFN-α DCs incubated or not with anti–LOX-1 mAb before the coculture with PHK26-PE–labeled AC. (A,C,E) After a 24-hour coculture, IFN-α DCs were fixed, made permeable, and stained with FITC-conjugated anti–MHC-I (A), anti–MHC-II (C), or with LAMP-2 (E) antibodies. Colocalization of staining is shown in merged images (yellow). In panels B and D, the up-regulation of MHC-I and MHC-II levels on unfixed IFN-α DCs was analyzed over time, after 3 and 24 hours of coculture with ACs. Scale bars correspond to 10 μm. Images were observed through a 63× oil-immersion objective lens. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

MHC-I and MHC-II molecules rearrange and colocalize with ACs in IFN-α DCs upon AC uptake. CLSM analysis (central optical sections) of IFN-α DCs incubated or not with anti–LOX-1 mAb before the coculture with PHK26-PE–labeled AC. (A,C,E) After a 24-hour coculture, IFN-α DCs were fixed, made permeable, and stained with FITC-conjugated anti–MHC-I (A), anti–MHC-II (C), or with LAMP-2 (E) antibodies. Colocalization of staining is shown in merged images (yellow). In panels B and D, the up-regulation of MHC-I and MHC-II levels on unfixed IFN-α DCs was analyzed over time, after 3 and 24 hours of coculture with ACs. Scale bars correspond to 10 μm. Images were observed through a 63× oil-immersion objective lens. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

MHC-I, MHC-II and LAMP-2 distribution after AC uptake in IL-4 DCs. CLSM analysis (central optical sections) of IL-4 DCs incubated or not with anti–LOX-1 mAb before 24-hour coculture with PHK26-PE–labeled ACs. DCs were fixed, made permeable, and then stained with FITC-conjugated anti–MHC-I (A), anti–MHC-II (B), or with LAMP-2 antibodies (C). Colocalization of ACs with the mentioned molecules is shown in yellow; scale bars, 10 μm. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

MHC-I, MHC-II and LAMP-2 distribution after AC uptake in IL-4 DCs. CLSM analysis (central optical sections) of IL-4 DCs incubated or not with anti–LOX-1 mAb before 24-hour coculture with PHK26-PE–labeled ACs. DCs were fixed, made permeable, and then stained with FITC-conjugated anti–MHC-I (A), anti–MHC-II (B), or with LAMP-2 antibodies (C). Colocalization of ACs with the mentioned molecules is shown in yellow; scale bars, 10 μm. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

We then performed CLSM of unfixed IFN-α DCs, an approach suitable for revealing MHC class I staining only on the surface membrane, thus considered as a possible index for measuring half-life of MHC class I–Ag complexes at this site. We found that the up-modulation of MHC class I on the membrane of IFN-α DCs was time dependent with respect to the initial coculture with ACs. In fact, after a 3-hour coculture of IFN-α DCs and APO-allo-PBLs, the level of MHC class I molecules on the membrane of IFN-α DCs was comparable with that observed in the untreated cells, whereas the expression of MHC class I at this site was markedly increased after a 24-hour coculture time (Figure 6B), thus suggesting a time-dependent accumulation of these molecules on DC membrane after AC exposure. Interestingly, in AC-loaded IFN-α DCs pretreated with anti-LOX antibody, the presence of MHC class I molecules on the membrane was significantly decreased along with decreased intracellular APO-allo-PBLs (Figure 6B). These findings strongly suggest that IFN-α in DCs not only regulate the synthesis of MHC class I molecules but also can control the surface turnover of MHC class I–Ag complexes. However, the analysis of MHC class II levels revealed that the expression of these molecules was comparable in both IFN-α DCs and IL-4 DCs (Figures 6C,7B). However, upon coculture with ACs, only IFN-α DCs showed an intracellular colocalization of MHC class II molecules with ACs (Figure 6C) along with a concomitant enhancement of MHC class II expression on the surface membrane over time (Figure 6D), suggesting an activation of the MHC class II–restricted presentation pathway. Of note, anti–LOX-1 antibody pretreatment of IFN-α DCs exposed to ACs significantly reduced the quantity of intracellular ACs and in turn the intracellular colocalization of these elements with MHC class II molecules. In parallel, the analysis of these processes in IL-4 DCs confirmed the lower ability of these cells in processing AC-associated antigens and the lack of LOX-1 involvement (Figure 7B).

We next examined the distribution of LAMP-2, a lysosome-associated membrane protein whose mRNA was significantly up-modulated in IFN-α DCs as revealed by microarray analysis. LAMP-2 expression was clearly detected in IFN-α DCs, and a clear-cut colocalization of phagocyted APO-allo-PBLs and LAMP-2 was observed in IFN-α DCs, along with increasing AC uptake (Figure 6E). When IFN-α DCs were preincubated with anti–LOX-1 antibody, the APO-allo-PBLs and LAMP-2 colocalization was inhibited in parallel with a reduced AC phagocytosis. In contrast, no differences were observed in the colocalization of APO-allo-PBLs and LAMP-2 in AC-loaded IL-4 DCs in the presence or absence of anti–LOX-1 antibody (Figure 7C).

Discussion

Apoptotic cell clearance is a complex event that may lead to tolerance rather than immunity. Induction of immunity is considered to be related to the capacity of DCs to undergo a special differentiation/activation process along with an acquired capability to present AC-derived Ags to T cells. Such features depend on the in vivo microenvironment and cytokine milieu, which can shape DC functions.3 Thus, the identification of key signals and molecules responsible for AC uptake by DCs and induction of T-cell immunity against AC-associated antigens as well as the characterization of the distinct DC subpopulation endowed with such properties are major challenges in immunology, with important implications for the treatment of some immune-related diseases such as cancer and autoimmunity.9,31

In the present study, we evaluated the role of IFN-α in controlling the expression and the function of molecules that render DCs competent in taking up and processing antigens from ACs, crucial processes needed to drive the immune response in physiologic and pathologic conditions. To this end, we first performed comparative studies of gene expression profiles of monocyte-derived DCs with the purpose of identifying putative genes/proteins potentially involved in AC uptake and induction of T-cell immunity by DCs. In particular, we used highly active IFN-α–conditioned DCs generated from monocytes after a single-step treatment with IFN-α as an in vitro model mimicking natural DCs rapidly generated in response to infections and other danger stimuli,32 in comparison with IL-4 DCs, the more conventional DC in vitro system. We found that, although the genes up-regulated in IFN-α DCs belonged to immunologic pathways, those typical of IL-4 DCs proved to be related to metabolic pathways, suggesting that IL-4 DCs can indeed be defined as “disabled DCs,”33 not representing active DCs generally observed in the course of immune response to danger signals. In particular, IFN-α DCs exhibited an overexpression of an ensemble of genes belonging to the SR family compared with IL-4 DCs, including the main Hsp70-binding receptor LOX-1.

Recently, the potential importance of LOX-1 in the immune response has been highlighted.3 For instance, the block of LOX-1 has been reported to inhibit the binding of ACs on macrophages implying that these cells may display oxidized motifs through which bind members of SR family. Likewise, it has been reported that the expression of LOX-1 in endothelial cells is very low but can be rapidly induced by pro-oxidant and proinflammatory stimuli, including TNF-α and IL-1-β, which are 2 cytokines involved in the stimulation of inflammatory reaction by DCs.34,35 In addition, LOX-1 can mediate cross-presentation of Hsp70-associated ovalbumin in DCs.13,14 In the present study, we were able to identify LOX-1 as a DC signal essential for AC uptake and subsequent T-cell immunity. In fact, we found that treatment of IFN-α DCs with anti–LOX-1 antibody resulted in inhibitory effects not only on Hsp70 binding and Hsp70-induced DC functional activation but also on the uptake of ACs and subsequent presentation of AC-derived antigens to CD8+ effector T cells (cross-presentation) and to CD4+ T helper. In this regard, it has been reported that antigens associated to Hsp are channeled into MHC class I processing pathway to be presented to CD8+ T cells.36,37 In addition, the authors of recent studies38,39 have highlighted that the simultaneous activation of CD4+ T cells by Hsp-Ag complexes provokes a greater activation of CD8+ T cells, suggesting a role of CD4+ T helper cells in priming, expansion, and survival of CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Thus, we envisage that Hsp70-antigen complexes from ACs can bind LOX-1 in IFN-α DCs. Overall, IFN-α may represent the key signal that instructs DCs for LOX-1 expression, subsequent AC up-take, and activation of intracellular pathways for the simultaneous MHC class I– and class II–restricted presentation of AC-associated antigens to activate both CD8+ T effector and CD4+ T helper cells.

Recently, it has been reported that murine CD8α+ DCs are specialized in cross-presentation and that this tightly restricted function is ascribed to the capacity of these cells to perform mannose receptor-mediated endocytosis and to the increased expression of specific proteins involved in antigen processing,40,41 suggesting the existence of a subset of DCs specialized for maximizing MHC class I–restricted presentation. These findings may apparently be in contrast with the present data demonstrating that the expression of LOX-1 induced by IFN-α can represent a crucial event for rendering a defined set of naturally occurring DCs capable of simultaneously activating both MHC class I– and class II–restricted antigen presentation. However, it should be noted that the ability to process and present antigens by DCs also can be affected by the nature of the antigen cargo.42 Consistently with this hypothesis, we have found that only after AC capture MHC class I and class II molecules were significantly rearranged into IFN-α–conditioned DCs. In fact, both MHC molecules strongly colocalized with ACs and LOX-1 resulted to be involved in these phenomena specifically in DCs differentiated in the presence of IFN-α. Thus, IFN-α exposure can shape DCs by simultaneously promoting LOX-1–mediated endocytosis of ACs and inducing molecules that belong to MHC class I– and class II–restricted pathways. Both events render DCs equipped to promote the processing of AC-associated antigens at once by MHC class I– and class II–restricted mechanisms. In this regard, IFN-α DCs showed high levels of LAMP-2 expression as well as a strong colocalization of LAMP-2 with ACs into the cytosol, which was prevented by anti–LOX-1 antibody. LAMP-2 uniquely regulates the pathway for cytoplasmic antigen presentation by MHC class II molecules.43 Because MHC class I and MHC class II molecules can cross over in their access and surveillance of intracellular compartments for antigens derived from exogenous insults and self components, the ability of MHC class II to access cytoplasmic peptides via LAMP-2 could represent an important mechanism by which the response to AC-associated antigens is potentiated. Therefore, the up-regulation of LAMP2 by IFN-α could account for a more efficient stimulation of CD4+ T helper cells promoting, along with an amplified cross-priming of CD8+ T effector cells, a long-lasting and durable immunity after uptake of ACs by DCs.

Indeed, DCs pulsed with ACs as a source of antigens have been reported to induce under certain conditions cross-priming of CD8+ T cells.44 However, the DC phenotype and molecules endowed with such distinct capability had remained so far unclear. On the other hand, it has been reported that an Ag-specific CD4+ T-cell response may be generated by DCs loaded with cancer ACs in the presence of IFN-α.45 Altogether, the results presented in this study provide new evidence that under certain immunologic circumstances, such as the differentiation in the presence of IFN-α, DCs may exhibit a special capability to take-up ACs and induce both CD8+ and CD4+ T-cell responses by controlling different phases of these processes, including a LOX-1–dependent AC uptake as a first necessary step.

An ensemble of studies published during the past 10 years have emphasized the importance of interactions between IFN-α and DCs in linking innate and adaptive immunity.23,46 In this regard, the present results support the concept that IFN-α can represent the physiologic first signal responsible for triggering a broad spectrum of T-cell immunity through the activation of the LOX-1 pathway in DCs. This IFN-α–mediated pathway may play a role in the pathogenesis of certain autoimmune diseases that might be caused by IFN-α.47 Of note, signs of autoimmune disease have been observed frequently in IFN-treated patients, and their extent also has been correlated with the clinical response.48 Likewise, endogenous IFN-α production has been linked to distinct autoimmune diseases, possibly by inducing a rapid differentiation of DCs from monocytes.46,49 In conclusion, our results provide new evidence on the importance of the IFN-α/LOX-1 axis in some fundamental functions of naturally occurring DCs that may play beneficial or deleterious effects in cancer versus autoimmune diseases. All this may open novel perspectives for innovative protocols for cancer vaccination or autoimmunity treatment.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Ferrantini for helpful suggestions, F. Urbani for advice on statistical analysis, and Cinzia Gasparrini for secretarial assistance.

This work was supported in part by grants from the Italian Association for Research against Cancer (AIRC) and from the Italian Ministry of Welfare (PIO).

Authorship

Contribution: S.P. designed, performed, and analyzed experiments in collaboration with G.R. and under the supervision of L.G.; P.S. analyzed microarray data; I.C. assisted in microarray and functional experiments; P.B. provided expertise in phagocytosis experiments; F.S. and C.R. provided expertise in fluorescence microscopy analysis; S.B. and I.F. provided rat anti–human LOX-1 antibody and performed and analyzed Western blot experiments; F.B., L.G., and S.P. prepared the manuscript; and F.B. and L.G. provided intellectual guidance on the project.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Dr Filippo Belardelli, Department of Cell Biology and Neurosciences, Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Viale Regina Elena 299 Rome, 00161, Italy; e-mail: filippo.belardelli@iss.it.

![Figure 3. Hsp70-binding activity of LOX-1 in IFN-α DCs. (A) IFN-α DCs and IL-4 DCs were incubated with a neutralizing anti–LOX-1 mAb (blue lines) or isotype control anti-IgG1 mAb (red lines). After 20 minutes, Hsp70-FITC was added to the cultures and revealed by fluorescence-activated cell-sorting analysis. Black and yellow lines represent, respectively, Hsp70-treated DCs and DCs cultured alone. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments. (B) Allostimulatory capacity of IFN-α DCs cultured in the presence or absence of Hsp70. IFN-α DCs were also preincubated with anti–LOX-1 or isotype control IgG1 mAbs. The proliferation of allogeneic T cells cocultured with DCs at the indicated ratio was determined by [3H]thymidine incorporation. The results represent the mean ± SD of data obtained from 3 different experiments.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/115/8/10.1182_blood-2009-07-234468/4/m_zh89990948620003.jpeg?Expires=1767818843&Signature=o5XnCmPFGisB4Q1UKe6rhrif40emZsmsmPq-Ob1o6zma0jfR96ij9qrocZASTi6Pu7uckJgLciNxf2BP9VXE~n8FjX~LkVycFmBzyRGMi~kArgkVTKOXcYvzmwDHxLDLNbfI1VnzDhvjcWnkGGVKtyablYrIre2jVd1rM1I0AgQcG1xoeBBd-tRnvfUE09N8M8RvEEVDpHxFKxEKfxkCwNj2MPxNNBBa02oYzM0P~nJl0qRbxnkfOpN02cR6-rlJvrOLsY7~I~0hQuiBWdSObBEoaD9uSZNJ0tOooAjC6LRe4yidK-ZvWeebYmR27gqHt9--9T12llq5ugR6U3LkCg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)