Abstract

In this issue of Blood, Lokhorst and colleagues report on the results of HOVON-50, a phase 3 randomized trial designed to evaluate the effects of thalidomide during induction treatment and as maintenance in patients with multiple myeloma. There were 556 patients randomly assigned either to 3 cycles of VAD or to TAD. All patients were to receive high-dose melphalan with autologous stem cell support followed by maintenance with interferon for the VAD arm or thalidomide for the TAD arm.1 This study together with other randomized and nonrandomized trials establish a definitive role for thalidomide as induction therapy in conjunction with dexamethasone, anthracyclines, and alkylating agents.

Since the discovery of its activity against multiple myeloma, the role of thalidomide in the treatment of myeloma has been extensively explored.2 The HOVON-50 study represents the latest of these large, randomized trials whose primary objective is to define the role of thalidomide as induction and maintenance therapy for myeloma. The addition of thalidomide to the combination of an anthracycline and steroids was associated with a significantly improved overall response rates prior to high-dose therapy (71% vs 57%), including a significantly higher rate of very good partial response (90% or more reduction in tumor burden) of 37% versus 18% for the vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone (VAD) arm. However, the relevance of these findings in the context of newer induction therapies combining the proteosome inhibitor bortezomib, an immunomodulatory drug (IMID; such as thalidomide or lenalidomide), and steroids remains to be determined.3-6

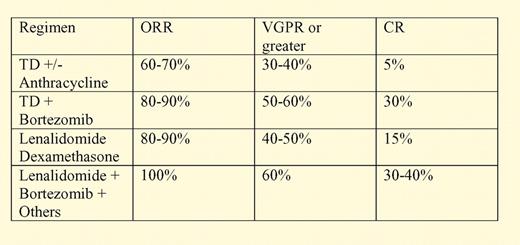

This point is illustrated in the table, which compares the response rates of standard thalidomide-containing induction regimens with more modern bortezomib-IMID combinations. Thus, traditional thalidomide-based induction either with steroids alone or in combination with an anthracycline or an alkylator may be better than nonthalidomide-based inductions. The results may be inferior to what can now be obtained with IMID-bortezomib combinations.

Underscoring this point are the results of the most recent GIMENA trial presented by Cavo et al at the American Society of Hematology meeting in San Francisco. In the study, 450 patients with newly diagnosed myeloma were randomized to receive thalidomide in combination with dexamethasone either with or without bortezomib. Patients randomized to the bortezomib arm had a significantly higher response rate and complete response rate than those who did not receive bortezomib. More importantly, progression-free survival at 2 years was 90%, significantly better than the 80% seen in the thalidomide dexamethasone arm, with as yet no significant impact on overall survival at 2 years (96% vs 91%).3

The HOVON-50 trial confirms the beneficial role of thalidomide as maintenance therapy after autologous stem cell transplantation with an improvement in median progression-free survival from 22 months to 34 months. No survival benefit for thalidomide maintenance was seen due to the shortened survival after relapse seen in the thalidomide arm, but only 50% of patients received salvage bortezomib and less than 20% received lenalidomide therapy.

In summary, the results of HOVON-50 strongly support the use of thalidomide as induction and maintenance therapy in patients with myeloma. However, in the context of emerging data from ongoing trials using bortezomib and lenalidomide combinations, the tad improvement obtained with thalidomide, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone (TAD) may just not be the best that can be obtained with current therapy. Large, randomized trials are currently ongoing to address this and other clinically relevant questions in myeloma therapy today. We should all continue to support them.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: S.G. is on the speakers bureau of Celgene, Novartis, Millennium, and Genzyme. ■