Abstract

Interactions between histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACIs) and the novel proteasome inhibitor carfilzomib (CFZ) were investigated in GC- and activated B-cell–like diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (ABC-DLBCL) cells. Coadministration of subtoxic or minimally toxic concentrations of CFZ) with marginally lethal concentrations of HDACIs (vorinostat, SNDX-275, or SBHA) synergistically increased mitochondrial injury, caspase activation, and apoptosis in both GC- and ABC-DLBCL cells. These events were associated with Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) and p38MAPK activation, abrogation of HDACI-mediated nuclear factor-κB activation, AKT inactivation, Ku70 acetylation, and induction of γH2A.X. Genetic or pharmacologic JNK inhibition significantly diminished CFZ/vorinostat lethality. CFZ/vorinostat induced pronounced lethality in 3 primary DLBCL specimens but minimally affected normal CD34+ hematopoietic cells. Bortezomib-resistant GC (SUDHL16) and ABC (OCI-LY10) cells exhibited partial cross-resistance to CFZ. However, CFZ/vorinostat dramatically induced resistant cell apoptosis, accompanied by increased JNK activation and γH2A.X expression. Finally, subeffective vorinostat doses markedly increased CFZ-mediated tumor growth suppression and apoptosis in a murine xenograft OCI-LY10 model. These findings indicate that HDACIs increase CFZ activity in GC- and ABC-DLBCL cells sensitive or resistant to bortezomib through a JNK-dependent mechanism in association with DNA damage and inhibition of nuclear factor-κB activation. Together, they support further investigation of strategies combining CFZ and HDACIs in DLBCL.

Introduction

Diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is an aggressive form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) that accounts for 30% to 40% of the total incidence of NHL. Patients with DLBCL have been divided into 3 groups according to their gene profiling patterns: germinal-center B-cell–like DLBCL (GCB-DLBCL), activated B-cell–like DLBCL (ABC-DLBCL), and mediastinal or unclassified type.1 These subcategories are characterized by distinct differences in survival, chemoresponsiveness, and dependence on signaling pathways, particularly nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB).2 Aside from those patients eligible for allogeneic or autologous stem cell transplantation, combination chemotherapy offers a potentially curative option for a subset of DLBCL patients.3 However, responses to cytotoxic chemotherapy (eg, rituximab with Cytoxan, hydroxyrubicin, Oncovin, and prednisone) vary considerably depending on multiple factors, including disease stage and genetic profile, among others. In particular, patients with the ABC-DLBCL subtype, which is NF-κB–dependent,4 appear to have a significantly worse prognosis than other subtypes.5 Collectively, these considerations have prompted the search for more effective treatment strategies in DLBCL.

Acetylation of positively charged lysine residues within the histone tails of nucleosomes represents an important epigenetic mechanism through which gene expression is modified. Histone acetylation is reciprocally regulated by histone deacetylases (HDACs), of which at least 15 have been identified, and histone acetylases.6 In general, acetylation of histone tails favors an open chromatin structure that is more conducive to gene expression.7 Histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACIs) represent a class of agents that promote gene expression, including those that regulate cell differentiation and death.8 Some HDACIs primarily target a single HDAC (eg, the class IIb HDAC6 by tubacin),9 whereas others target a class of HDACs, for example, MCD01003, which inhibits class I nuclear HDACs. On the other hand, hydroxamate HDACIs, such as vorinostat or LBH-589, function as pan-HDACIs and target both class I and class II (including class IIb) HDACs.10 HDACIs kill cells through diverse mechanisms, including induction of oxidative injury,11 up-regulation of death receptors, cell-cycle checkpoint disruption,12 interference with Hsp90 function, up-regulation of proapoptotic proteins, for example, Bim, and interference with proteasome function,13 among others. The pan-HDACI vorinostat initially displayed single-agent activity in acute myeloid leukemia,14 and it has recently been approved for the treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.15 On the other hand, the activity of single-agent vorinostat in relapsed/refractory DLBCL is more limited.16

The 26S proteasome plays a critical role in cellular homeostasis and has become a major target for therapeutic intervention, that is, by proteasome inhibitors (PIs). The catalytic 20S core of the proteasome consists of chymotrypsin-like (C-T), trypsin-like (T), and caspase-like (C) activities, which are variably inhibited by PIs.17 The mechanisms by which PIs induce cell death remain to be fully elucidated but have been attributed to induction of oxidative injury,18 disruption of protein homeostasis,19 and inhibition of NF-κB through stabilization of IκBα,20 among others. Notably, proteasome inhibitors have been reported to exert selective lethality toward transformed cells.21 Consistent with this notion, bortezomib (Velcade), the first proteasome inhibitor to enter the clinic, has shown significant activity in multiple myeloma and has been approved for the treatment of refractory disease.22 Bortezomib has also been approved for the treatment of certain forms of NHL, for example, mantle cell lymphoma.23 However, its role, either alone or in combination with chemotherapy in DLBCL, remains to be defined.24 The preexistence or development of bortezomib resistance has prompted the development of several novel proteasome inhibitors.25 One such agent, carfilzomib (PR-171; CFZ) is an epoxyketone that, in contrast to bortezomib, is an irreversible inhibitor of the 26S proteasome.17,26 In preclinical studies, CFZ has shown activity against certain bortezomib-resistant cell types,26 and it is currently undergoing clinical evaluation in multiple myeloma and other hematopoietic malignancies.27 Its activity in DLBCL has not yet been fully evaluated.

Preclinical studies have documented synergistic interactions between proteasome inhibitors, such as bortezomib, and HDAC inhibitors in diverse malignant cell types, particularly those of hematopoietic origin, including multiple myeloma,28 myeloid leukemia, lymphoma,29 and chronic lymphocytic leukemia,30 among others. Potential mechanisms of synergism include (1) interruption of NF-κB activation by bortezomib, which promotes HDACI lethality,30 (2) disruption of aggresome function by class IIb HDACIs,28 and (3) induction of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress.31 Notably, results of recent trials indicate that regimens combining bortezomib and vorinostat display significant activity in refractory multiple myeloma, including disease that has progressed after bortezomib treatment.32 Collectively, these findings raise the possibility that a dual strategy (using second-generation, irreversible proteasome inhibitors and enhancing the activity of such agents by combining them with HDACIs) might be effective in DLBCL. The purpose of the present study was to determine whether indeed class I HDACIs, such as vorinostat, which also inhibit HDAC6, could enhance the activity of the novel proteasome inhibitor CFZ in DLBCL cells, including those resistant to bortezomib alone. Our results indicate that vorinostat and CFZ interact in a highly synergistic manner in both ABC- and GC-DLBCL, that these events involve activation of the stress-related Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) kinase and inhibition of NF-κB, and occur in primary DLBCL specimens. Significantly, the CFZ/vorinostat regimen displays pronounced activity in bortezomib-resistant cells and in in vivo DLBCL xenograft models.

Methods

Cells

SUDHL16 cells (GC subtype) were a kind gift from Dr Alan Epstein (University of Southern California). SUDHL4 and SUDHL6 (both GC) and OCI-LY10 and OCI-LY3 (both ABC) were provided by Dr Lisa Rimsza (University of Arizona). Bortezomib-resistant SUDHL16-10BR (GC), OCI-LY10-40BR (ABC), and Raji (20-BR) were generated by exposing the respective parental cells to progressively increasing concentrations of bortezomib beginning with 1.0nM. Once cells developed resistance to bortezomib, they were cultured in the absence of drug for 2 weeks before experiments. Multiple studies documented the persistence of drug resistance under these conditions. SUDHL16-sh-JNK cells were generated by electroporation (Amaxa) using buffer L as described previously.33 SUDHL16-JNK-DN lines were generated similarly by stably transfecting APF cDNA (provided by Dr S. Korsmeyer, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute) into SUDHL16 cells. Cells ectopically expressing activated AKT were generated by transfecting pUSE-myr-AKT1 cDNA (Upstate Biotechnology) into SUDHL16 cells as described previously.33 Stable clones were selected by serial dilution using G418 as a selection marker. Cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals) and nutrients as previously described.33 Experiments were performed with logarithmically growing cells (eg, 4.0-5.0 × 105 cells/mL) and passages 6 to 25 to ensure uniform responses. Mycoplasma tests were uniformly negative (MycoAlert Mycoplasma Detection Kit; Lonza Rockland).

Reagents

CFZ was provided by Onyx Pharmaceuticals. Bortezomib (Velcade) was provided by Millennium Pharmaceuticals. Vorinostat was provided by Merck & Co. SNDX-275 was provided by Syndax Pharmaceuticals. 7-Amino-actinomycin D (7-AAD) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. JNK inhibitor (ALX-159-600) was obtained from Axxora Platform. SBHA was purchased from Biomol. All agents were formulated in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO).

Experimental format

Cells were suspended in sterile plastic T-flasks (Corning) in the presence or absence of drugs, after which they were placed in a 5% CO2, 37°C incubator for various intervals. At the end of the incubation period, cells were transferred to sterile centrifuge tubes, pelleted by centrifugation at 400g for 10 minutes at room temperature, and prepared for analysis for cell death, protein expression, and so forth.

Assessment of cell death and apoptosis

Drug effects on cell viability were monitored by flow cytometry using 7-amino actinomycin D staining as previously described.34 Alternatively, annexin V/propidium iodide staining (both BD Biosciences PharMingen) was used to monitor early (annexin V+) or late (annexin V+, propidium iodide+) apoptosis as before.34 In all studies, a high degree of equivalence was observed between results of 7-AAD and annexin V/propidium iodide assays.

Collection and processing of primary normal CD34+ and DLBCL cells

Normal human bone marrow mononuclear cells were obtained with informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki from the bone marrow of patients undergoing routine bone marrow aspirations for nonmyeloid hematologic disorders as described in detail previously.34 These studies have been approved by the Investigational Review Board of Virginia Commonwealth University. CD34+ cells were isolated using an immunomagnetic bead separation technique.34 CD34+ cells were then suspended in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal calf serum and exposed to agents, as in the case of continuously cultured cell lines. Parallel studies were performed in primary DLBCL cells obtained from the bone marrow of 3 patients with DLBCL and extensive marrow infiltration (> 70%).

Western blot analysis

Western blot samples were prepared from whole cell pellets. Equal amounts of protein (20 μg) were separated by 4% to 12% Bis-Tris (Invitrogen) precast gels and probed with primary antibodies of interest as described.34 The sources of primary antibodies were as follows: pAKT, AKT1,Ku70, Ku86, cytochrome c, p-JNK, JNK1, p-ERK, ERK, GRP94, GRP78, and XBP were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Cleaved caspase-8, cleaved caspase-3, p-p38, p38, p-eIF4E, CF caspase 9, p-SEK1, SEK1, acetylated-lysine, and P-histone-H2AX were from Cell Signaling Technology. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP; C-2-10) and SMAC were from Upstate Biotechnology. Caspase-8 was from Alexis. Tubulin was from Oncogene. Actin was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Bcl-2 was from Dako. Caspase 4 was obtained from Assay Designs.

S-100 fractions

S-100 (cytosolic) fractions were obtained by sucrose gradient centrifugation as previously described.34

NF-κB activity

Nuclear protein was extracted using Nuclear Extract Kit (Active Motif). NF-κB activity was determined using an enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) Kit TransAM NF-κB p65 Transcription Factor Assay Kit (Active Motif), according to the manufacturer's instructions.35

EMSA

Consensus oligonucleotides corresponding to the sites of the immunoglobulin κlight-chain enhancer binding for NF-κB were purchased from Promega and labeled with [γ-32P]ATP. Nuclear extracts were prepared using NE-PER nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction reagents as described in “NF-κB activity.” A total of 5 μg/condition of nuclear proteins was subjected to electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) for NF-κB/DNA binding as described previously in detail.36

Cell-cycle analysis

The cell-cycle distribution of cells after drug treatment was determined by flow cytometry using a commercial software program (Modfit; BD Biosciences) as per standard protocol.

Proteasome inhibition assays

Cells were cultured in 6-well plates at 1.0 × 106 cells per condition. After a treatment period ranging from 1 to 4 hours, cells were pelleted and washed 3 times with RPMI 1640 and once with phosphate-buffered saline. Cells were then resuspended in 50 μL of TE buffer (20mM Tris, pH 8.0, 5mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) and lysed using multiple freeze/thaw cycles. Lysate protein concentrations were determined and equalized with TE buffer. Assays were performed in 96-well black color plates using 50 μL of cell lysate and 50 μL of 2× substrate buffer, composed of 120μM Suc-LLVY-7-amino-4-methylcoumarin (Boston Biochem), 20mM Tris pH 8.0, 5mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, and DMSO. Fluorescence was read on the Victor3 Multilabel Counter (PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences) at 340/465 nm excitation/emission every 2 minutes for 20 to 30 minutes. Relative fluorescence unit data were plotted using GraphPad Prism software, fit to linear curves, and analyzed for slope by statistical analysis. Individual slopes represent proteasome activity.17

Animal studies

Animal studies were performed in Beige-nude-XID mice (NIH-III; Charles River). A total of 10 × 106 OCI-LY10 or SUDHL4 cells were pelleted, washed twice with 1 times phosphate-buffered saline, and injected subcutaneously into the right flank. Mice were monitored 2 or 3 times a week for the appearance of tumors. Once the tumors were visible, 5 or 6 mice were treated with various concentrations of CFZ via tail vein (intravenous bi-weekly [BIW]) injection (days 1, 2, 8, 9, 15, 16, etc); vorinostat was administered intraperitoneally TIW (twice weekly; days 1, 2, 3, 8, 9, 10, etc). Tumor volume was measured 2 or 3 times per week with calipers using the following formula: tumor volume (mm3) = length (mm) × width (mm)2. Mice were killed when tumor size exceeded 2000 mm3.37 Mouse weights were measured periodically as an indicator of toxicity.

Formulation of CFZ and vorinostat for in vivo studies

Vorinostat was dissolved in DMSO and stored in −80°C in small aliquots. It was diluted in 1:1 PEG400 and sterile water to a final composition of 10% DMSO, 45% PEG400, 45% water. Treatment volumes for each mouse were less than or equal to 100 μL. Stock CFZ was prepared with 10% sulfobutylether betacyclodextrin in 10mM citrate buffer, pH 3.5 (vehicle), at 2 mg/mL and stored at −80°C. Stock CFZ solutions were diluted daily with vehicle before injection.

TUNEL assays of tissue sections

After processing tissues as previously described,37 100-μL sample aliquots were applied to slides by cytospin. TdT-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assays were performed with fluorescein-12-dUTP using a terminal transferase recombinant kit (Roche) and Vectashield/propidium iodide kit (Vectashield) as per the manufacturer's protocol.33

Statistical analysis

The significance of differences between experimental conditions was determined using the 2-tailed Student t test. Characterization of synergistic and antagonistic interactions was performed using median dose effect analysis in conjunction with a commercially available software program (CalcuSyn; Biosoft).34

Results

CFZ interacts synergistically with HDACIs to induce apoptosis in DLBCL cells in a time- and concentration-dependent manner

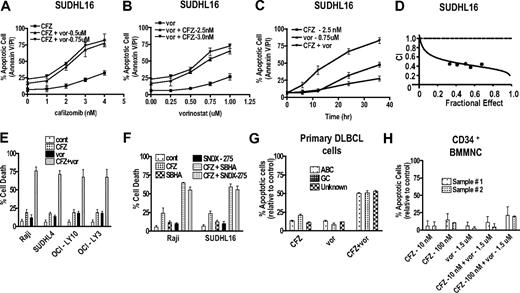

Exposure (24 hours) of SUDHL16 cells to low nanomolar concentrations of CFZ were minimally toxic by themselves, but when combined with pharmacologically achievable concentrations of vorinostat (0.5 or 0.75μM), resulted in a marked increase in apoptosis for CFZ concentrations more than or equal to 2nM (Figure 1A). Analogously, the lethality of marginally toxic vorinostat concentrations was significantly increased by coexposure to more than or equal to 2.5nM CFZ (Figure 1B). In separate studies, sequential treatment with CFZ before or after vorinostat also significantly enhanced lethality but was less effective than simultaneous treatment (data not shown). The increased lethality of the CFZ/vorinostat regimen was readily apparent within 12 hours of treatment and increased further subsequently (Figure 1C). Median dose effect analysis revealed combination index values significantly less than 1.0, indicating a synergistic interaction (Figure 1D). Very similar interactions were observed in other malignant B-cell lines (Figure 1E), including Raji, SUDHL4 (GC subtype), and OCI-LY10 and LY-3 (ABC subtype). Sharply enhanced lethality also occurred in cells exposed to CFZ in combination with other HDACIs, including SNDX-275 or SBHA (Figure 1F). Finally, combined exposure to CFZ and vorinostat (24 hours) resulted in a marked increase in lethality in 3 primary DLBCL samples (1 GC, 1 ABC, and 1 unspecified) but exhibited relatively modest lethality toward normal CD34+ cells (Figure 1G-H).

Cotreatment with CFZ and HDACIs leads to synergistic induction of cell death in DLBCL (both GC and ABC) cells and primary DLBCL cells, but not in normal hematopoietic cells. (A) SUDHL16 cells were treated with various CFZ concentrations (1.0-4.0nM) in conjunction with fixed vorinostat (0.5 or 0.75mM) concentrations for 36 hours, after which cell death was monitored by flow cytometry and annexin V/propidium iodide staining. (B) SUDHL16 cells were treated with various vorinostat (0.25-1.0μM) concentrations in the presence or absence of fixed concentrations of CFZ (2.5 or 3.0nM) for 36 hours, after which cell death was monitored by flow cytometry and annexin V/propidium iodide staining. (C) SUDHL16 cells were treated with CFZ 2.5nM with or without vorinostat 0.75μM for the indicated intervals, after which cell death was monitored by flow cytometry and annexin V/propidium iodide staining. (D) Fractional effect values were determined by comparing results obtained for untreated controls and treated cells after exposure to agents administered at a fixed ratio, after which median dose effect analysis was used to characterize the nature of the interaction. Combination index (CI) values less than 1.0 denote a synergistic interaction. (E) Cells were treated with minimally toxic concentrations of CFZ (Raji 5nM, SUDHL4 4nM, OCI-LY10 7nM, OCI-LY3 5nM) in the presence or absence of vorinostat (Raji 2.0μM, SUDHL4, OCI-LY10, OCI-LY3 1.5μM) for 48 hours, after which cell death was monitored by 7-AAD and 3,3-dihexyloxacarbocyanine iodide (DiOC6) staining. (F) Raji and SUDHL16 cells were treated with minimally toxic concentrations of CFZ (SUDHL16 3nM, Raji 5nM), SBHA (SUDHL16 30μM, Raji 50μM), and SNDX-275 (1.0μM) for 36 to 48 hours, after which cell death was monitored by 7-AAD and DiOC6 staining. (G) Primary human DLBCL cells were isolated as described in “Methods” and resuspended in medium containing 10% fetal calf serum at a cell density of 0.75 × 106/mL cells. They were then treated with CFZ (ABC sample 2nM, GC sample 100nM, unknown type 4nM) with or without vorinostat (ABC sample 0.5μM, GC sample 1.0μM, unknown type 0.75μM) for 16 hours. The percentage of apoptotic cells was monitored by annexin V/propidium iodide staining, and the percentage of dead cells was normalized to controls. Viability of the 3 primary specimens without treatment was 60% to 70%, 80% to 85%, and 70% to 75% for the ABC, the GC, and the unknown types, respectively. (H) CD34+ cells were collected from the bone marrow, isolated by an immunomagnetic bead separation technique as described in “Methods,” and exposed to CFZ with or without vorinostat as indicated for 48 hours. Cell death was monitored by annexin V/propidium iodide staining, and the percentage of apoptotic cells was normalized to controls. For all studies, values represent the means for 3 experiments performed in triplicate plus or minus SD.

Cotreatment with CFZ and HDACIs leads to synergistic induction of cell death in DLBCL (both GC and ABC) cells and primary DLBCL cells, but not in normal hematopoietic cells. (A) SUDHL16 cells were treated with various CFZ concentrations (1.0-4.0nM) in conjunction with fixed vorinostat (0.5 or 0.75mM) concentrations for 36 hours, after which cell death was monitored by flow cytometry and annexin V/propidium iodide staining. (B) SUDHL16 cells were treated with various vorinostat (0.25-1.0μM) concentrations in the presence or absence of fixed concentrations of CFZ (2.5 or 3.0nM) for 36 hours, after which cell death was monitored by flow cytometry and annexin V/propidium iodide staining. (C) SUDHL16 cells were treated with CFZ 2.5nM with or without vorinostat 0.75μM for the indicated intervals, after which cell death was monitored by flow cytometry and annexin V/propidium iodide staining. (D) Fractional effect values were determined by comparing results obtained for untreated controls and treated cells after exposure to agents administered at a fixed ratio, after which median dose effect analysis was used to characterize the nature of the interaction. Combination index (CI) values less than 1.0 denote a synergistic interaction. (E) Cells were treated with minimally toxic concentrations of CFZ (Raji 5nM, SUDHL4 4nM, OCI-LY10 7nM, OCI-LY3 5nM) in the presence or absence of vorinostat (Raji 2.0μM, SUDHL4, OCI-LY10, OCI-LY3 1.5μM) for 48 hours, after which cell death was monitored by 7-AAD and 3,3-dihexyloxacarbocyanine iodide (DiOC6) staining. (F) Raji and SUDHL16 cells were treated with minimally toxic concentrations of CFZ (SUDHL16 3nM, Raji 5nM), SBHA (SUDHL16 30μM, Raji 50μM), and SNDX-275 (1.0μM) for 36 to 48 hours, after which cell death was monitored by 7-AAD and DiOC6 staining. (G) Primary human DLBCL cells were isolated as described in “Methods” and resuspended in medium containing 10% fetal calf serum at a cell density of 0.75 × 106/mL cells. They were then treated with CFZ (ABC sample 2nM, GC sample 100nM, unknown type 4nM) with or without vorinostat (ABC sample 0.5μM, GC sample 1.0μM, unknown type 0.75μM) for 16 hours. The percentage of apoptotic cells was monitored by annexin V/propidium iodide staining, and the percentage of dead cells was normalized to controls. Viability of the 3 primary specimens without treatment was 60% to 70%, 80% to 85%, and 70% to 75% for the ABC, the GC, and the unknown types, respectively. (H) CD34+ cells were collected from the bone marrow, isolated by an immunomagnetic bead separation technique as described in “Methods,” and exposed to CFZ with or without vorinostat as indicated for 48 hours. Cell death was monitored by annexin V/propidium iodide staining, and the percentage of apoptotic cells was normalized to controls. For all studies, values represent the means for 3 experiments performed in triplicate plus or minus SD.

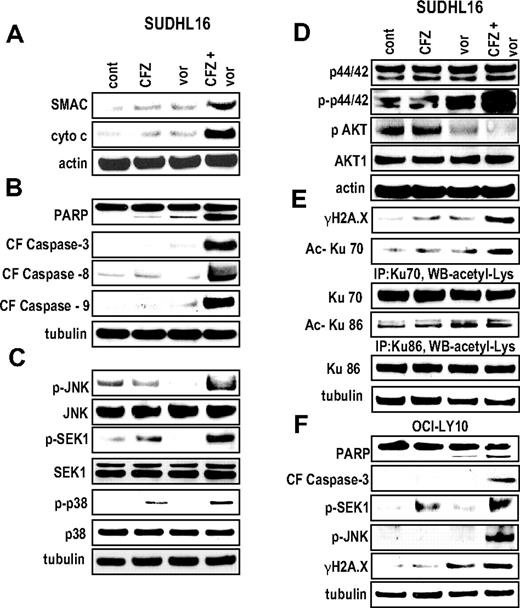

Combined treatment with CFZ and vorinostat is associated with mitochondrial injury, JNK activation, and DNA damage induction

Exposure of SUDHL16 cells to 3.0nM CFZ and 0.75μM vorinostat individually (14 hours) had little effect on Smac/Diablo or cytochrome c release, or activation of caspases-3, -8, or -9, whereas combined treatment markedly potentiated these events (Figure 2A-B). Combined treatment was associated with a sharp increase in phosphorylation of the stress-related kinase JNK and its upstream activator SEK1, accompanied by phosphorylation of p38MAPK (Figure 2C). Vorinostat modestly activated ERK1/2 in these cells, and this effect was increased by CFZ. On the other hand, vorinostat attenuated AKT phosphorylation, and combined treatment with CFZ essentially ablated phospho-AKT expression (Figure 2D).

Combined exposure of SUDHL16 and OCI-LY10 cells to CFZ and vorinostat leads to a pronounced increase in caspase activation, mitochondrial damage, JNK activation, and DNA damage. SUDHL16 cells were treated with CFZ (3.0nM) with or without vorinostat (0.75μM) for 14 hours. (A) Cytosolic (S-100) fractions were obtained as described in “S-100 fractions,” and the expression of cytochrome C and apoptosis inducing factor (AIF) was monitored by Western blot. (B-E) Proteins from whole-cell lysates were prepared, and expression of the indicated proteins was determined by Western blotting after drug exposure identical to that described in panel A. Expression of acetylated Ku70 and acetylated Ku86 was determined by immunoprecipitation with Ku70 and Ku86 antibodies followed by Western blotting with acetyl-Lys primary antibody. (F) OCI-LY10 cells were treated with CFZ (7.0nM) with or without vorinostat (1.5μM) for 24 hours. Cells were lysed, sonicated, proteins denatured, and subjected to Western blot analysis using the indicated primary antibodies. Each lane was loaded with 20 μg of protein; blots were stripped and reprobed with antibodies directed against tubulin or actin to ensure equivalent loading and transfer. Results are representative of 3 separate experiments.

Combined exposure of SUDHL16 and OCI-LY10 cells to CFZ and vorinostat leads to a pronounced increase in caspase activation, mitochondrial damage, JNK activation, and DNA damage. SUDHL16 cells were treated with CFZ (3.0nM) with or without vorinostat (0.75μM) for 14 hours. (A) Cytosolic (S-100) fractions were obtained as described in “S-100 fractions,” and the expression of cytochrome C and apoptosis inducing factor (AIF) was monitored by Western blot. (B-E) Proteins from whole-cell lysates were prepared, and expression of the indicated proteins was determined by Western blotting after drug exposure identical to that described in panel A. Expression of acetylated Ku70 and acetylated Ku86 was determined by immunoprecipitation with Ku70 and Ku86 antibodies followed by Western blotting with acetyl-Lys primary antibody. (F) OCI-LY10 cells were treated with CFZ (7.0nM) with or without vorinostat (1.5μM) for 24 hours. Cells were lysed, sonicated, proteins denatured, and subjected to Western blot analysis using the indicated primary antibodies. Each lane was loaded with 20 μg of protein; blots were stripped and reprobed with antibodies directed against tubulin or actin to ensure equivalent loading and transfer. Results are representative of 3 separate experiments.

In view of evidence that proteasome inhibitors promote ER stress,19 effects of CFZ (3.0nM) with or without 0.75μM vorinostat (14 hours) on various components of the unfolded protein response were examined in SUDHL16 cells. However, individual or combined treatment with these agents did not lead to changes in the expression of GADD153, IRE1α, ATF4, GRP78, GRP94, XBP1, or phospho-eI2Fα (data not shown).

Notably, expression of γH2A.X, a marker of double-stranded DNA breaks,38 was substantially increased in cells exposed to CFZ and vorinostat, and this was accompanied by acetylation of the DNA repair proteins Ku70 and Ku86 (Figure 2E). Lastly, ABC-type OCI-LY10 cells exposed to CFZ and vorinostat also displayed marked increases in PARP and caspase-3 cleavage, phosphorylation/activation of JNK and SEK1, and expression of γH2A.X (Figure 2F). These findings indicate that combined exposure of DLBCL cells to CFZ and vorinostat induces mitochondrial injury and caspase activation in association with activation of stress-related kinases and induction of DNA damage.

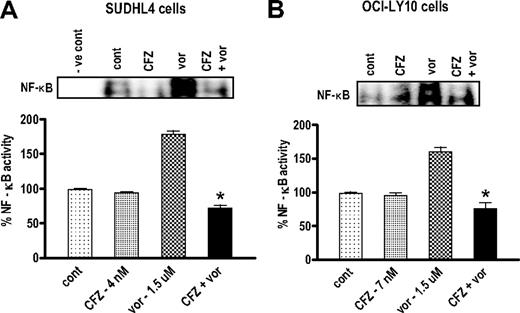

CFZ blocks HDACI-mediated NF-κB activation in both GC- and ABC-DLBCL cells

In light of the evidence that IκB kinase and proteasome inhibitors attenuate HDACI-induced NF-κB activation in various malignant hematopoietic cells,36 ELISA-based NF-κB activity assays were performed in both GC-DLBCL (SUDHL4) and ABC-DLBCL(OCI-LY10) cells exposed to vorinostat with or without CFZ. However, although CFZ alone did not lower basal NF-κB activity in either cell type, it effectively abrogated vorinostat-induced NF-κB activation in both SUDHL and OCI-LY10 cells (Figure 3). Results of EMSAs were consistent with these findings (Figure 3 inset). These findings indicate that CFZ blocks vorinostat-induced NF-κB activation in both GC- and ABC-DLBCL cells.

CFZ blocks HDACI-mediated NF-κB activation in both SUDHL4 and OCI-LY10 DLBCL cells. (A) SUDHL4 DLBCL cells were treated with CFZ (4.0nM) with or without vorinostat (1.5μM), and (B) OCI-LY10 DLBCL cells were treated with CFZ (7.0nM) with or without vorinostat (1.5μM) for 18 hours. Nuclear protein was extracted using Nuclear Extract Kit (Active Motif), and NF-κB activity was determined using an ELISA TransAM NF-κB p65 Transcription Factor Assay Kit (Active Motif), as described in “NF-κB activity.” Inset: After identical treatment, the same nuclear proteins were subjected to EMSA gel shift assays to assess NF-κB DNA binding as described in “NF-κB activity.” Values represent the means for triplicate determinations for 3 separate experiments. *Significantly less than values for vorinostat alone (P < .002).

CFZ blocks HDACI-mediated NF-κB activation in both SUDHL4 and OCI-LY10 DLBCL cells. (A) SUDHL4 DLBCL cells were treated with CFZ (4.0nM) with or without vorinostat (1.5μM), and (B) OCI-LY10 DLBCL cells were treated with CFZ (7.0nM) with or without vorinostat (1.5μM) for 18 hours. Nuclear protein was extracted using Nuclear Extract Kit (Active Motif), and NF-κB activity was determined using an ELISA TransAM NF-κB p65 Transcription Factor Assay Kit (Active Motif), as described in “NF-κB activity.” Inset: After identical treatment, the same nuclear proteins were subjected to EMSA gel shift assays to assess NF-κB DNA binding as described in “NF-κB activity.” Values represent the means for triplicate determinations for 3 separate experiments. *Significantly less than values for vorinostat alone (P < .002).

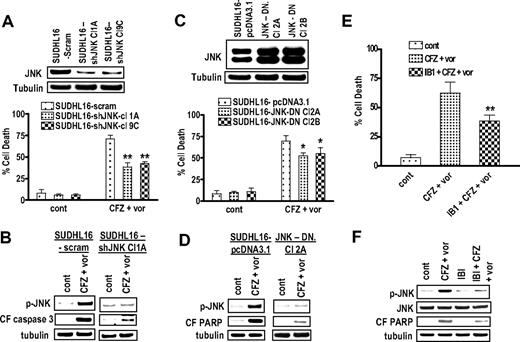

Activation of JNK plays a functional role in CFZ/vorinostat lethality in DLBCL cells

To determine the functional significance of JNK activation in CFZ/vorinostat lethality, SUDHL16 cells were stably transfected with JNK1 siRNA, and 2 clones, designated 1A and 9C, isolated. These cells displayed a clear reduction in JNK expression compared with scrambled sequence controls (Figure 4A inset). SUDHL16/1A and 9C cells were significantly less sensitive to CFZ/vorinostat lethality compared with controls (P < .01 in each case; Figure 4A). Notably, shJNK clones exhibited diminished CFZ/vorinostat-mediated JNK activation and caspase cleavage compared with controls (Figure 4B). In accord with these findings, stable transfection with JNK dominant-negative constructs (clones; Figure 4C inset) modestly but significantly reduced the lethality of this drug regimen (Figure 4C; P < .05). JNK-DN clones also displayed diminished CFZ/vorinostat-mediated JNK activation and PARP cleavage (Figure 4D). Finally, treatment of cells with a specific JNK-inhibitory peptide (IBI) significantly attenuated CFZ/vorinostat lethality (Figure 4E) and reduced JNK phosphorylation and PARP cleavage (Figure 4F). Together, these findings indicate that JNK activation plays a significant functional role in CFZ/vorinostat lethality toward DLBCL cells.

Pharmacologic and genetic interruption of the JNK pathways significantly diminishes CFZ/vorinostat lethality in SUHDL16 cells. (A) SUDHL16 cells stably transfected with JNK shRNA or vectors encoding a scrambled sequence were exposed to CFZ (3.0nM) plus vorinostat (0.75μM). After 36 hours of drug exposure, cell death was monitored by 7-AAD staining and flow cytometry. Inset: Relative expression of JNK protein in SUDHL16-scrambled sequence and shJNK clones. (B) After 14 hours of drug exposure as in panel A, Western blot analysis was used to monitor protein expression of phospho-JNK and the cleavage fragment of caspase-3 (CF caspase-3). (C) SUDHL16 cells stably transfected with JNK-DN cDNA or empty vector (pcDNA3.1) were exposed to CFZ (3.0nM) plus vorinostat (0.75μM). After 36 hours of drug exposure, cell death was monitored by 7-AAD staining and flow cytometry. Inset: Expression of JNK protein in SUDHL16 empty vector and JNK-DN clones. (D) After 14 hours of drug exposure as in panel C, Western blot analysis was used to monitor protein expression of phospho-JNK and cleaved PARP. (E) SUDHL16 cells pretreated with the selective JNK inhibitor IB1 (ALX 159-600; 10μM) for 2 hours were exposed to CFZ (3.0nM) plus vorinostat (0.75μM) for 36 hours. At the end of drug exposure, cell death was monitored by 7-AAD staining and flow cytometry. (F) After 14 hours of drug exposure as described in panel E, Western blot analysis was used to monitor protein expression of phospho-JNK, JNK, and cleaved PARP. For all studies, blots were stripped and reprobed with antitubulin antibodies to ensure equal loading and transfer of proteins. Each lane was loaded with 20 μg of protein. All values represent the means of triplicate experiments performed on 3 separate occasions plus or minus SD. (A,E) **Significantly less than values for scrambled sequence clone or control (P < .01). (C) *Significantly less than values for empty-vector controls (P < .05).

Pharmacologic and genetic interruption of the JNK pathways significantly diminishes CFZ/vorinostat lethality in SUHDL16 cells. (A) SUDHL16 cells stably transfected with JNK shRNA or vectors encoding a scrambled sequence were exposed to CFZ (3.0nM) plus vorinostat (0.75μM). After 36 hours of drug exposure, cell death was monitored by 7-AAD staining and flow cytometry. Inset: Relative expression of JNK protein in SUDHL16-scrambled sequence and shJNK clones. (B) After 14 hours of drug exposure as in panel A, Western blot analysis was used to monitor protein expression of phospho-JNK and the cleavage fragment of caspase-3 (CF caspase-3). (C) SUDHL16 cells stably transfected with JNK-DN cDNA or empty vector (pcDNA3.1) were exposed to CFZ (3.0nM) plus vorinostat (0.75μM). After 36 hours of drug exposure, cell death was monitored by 7-AAD staining and flow cytometry. Inset: Expression of JNK protein in SUDHL16 empty vector and JNK-DN clones. (D) After 14 hours of drug exposure as in panel C, Western blot analysis was used to monitor protein expression of phospho-JNK and cleaved PARP. (E) SUDHL16 cells pretreated with the selective JNK inhibitor IB1 (ALX 159-600; 10μM) for 2 hours were exposed to CFZ (3.0nM) plus vorinostat (0.75μM) for 36 hours. At the end of drug exposure, cell death was monitored by 7-AAD staining and flow cytometry. (F) After 14 hours of drug exposure as described in panel E, Western blot analysis was used to monitor protein expression of phospho-JNK, JNK, and cleaved PARP. For all studies, blots were stripped and reprobed with antitubulin antibodies to ensure equal loading and transfer of proteins. Each lane was loaded with 20 μg of protein. All values represent the means of triplicate experiments performed on 3 separate occasions plus or minus SD. (A,E) **Significantly less than values for scrambled sequence clone or control (P < .01). (C) *Significantly less than values for empty-vector controls (P < .05).

In contrast to these findings, stable transfection of SUDHL16 cells with constitutively active AKT constructs (AKT Cl3, Cl5, or Cl10) failed to protect cells from CFZ/vorinostat-induced apoptosis (supplemental Figure 1A, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article; P > .05). Similarly, coexposure of cells to the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 blocked CFZ/vorinostat-mediated p38 MAPK phosphorylation but did not significantly diminish cell death (P > .05; supplemental Figure 1B top panel; P > .05) or caspase-3 activation (supplemental Figure 1C bottom panel). These findings suggest that, in these cells, AKT down-regulation and p38 MAPK activation represent responses to CFZ/vorinostat but do not play a functional role in cell death.

Coadministration of vorinostat does not promote CFZ-mediated inhibition of DLBCL cell chymotryptic activity

In view of the evidence that HDACIs inhibit proteasome activity,13 the effects of coadministration of vorinostat on CFZ-mediated inhibition of chymotryptic activity was investigated in SUDHL16 and OCY-LY10 cells. As shown in Table 1, 3 to 7nM CFZ inhibited activity by 77% to 88% in these lines, whereas vorinostat (0.75-1.5μM) was without effect. Combination treatment did not result in further reductions in chymotryptic activity (P > .05 in each case). These findings argue against the possibility that interactions between CFZ and vorinostat in DLBCL cells stem from enhanced inhibition of chymotryptic activity.

Exposure of SUDHL16 and OCI-LY10 cells to CFZ results in a marked decrease in chymotrypsin-like proteasomal activity, an event that is not potentiated by vorinostat

| . | Chymotrypsin-like proteasome activity, RLU/5 μg of protein . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment . | SUDHL16 . | Percentage inhibition . | OCI-LY10 . | Percentage inhibition . |

| Control | 232 ± 2.4 | — | 198 ± 2.2 | — |

| CFZ | 26 ± 1.6 | 88 | 45 ± 2.5 | 77 |

| Vorinostat | 223 ± 1.7 | 4 | 194 ± 1.2 | 2 |

| CFZ plus vorinostat | 24 ± 1.1 | 89* | 44 ± 2.1 | 77* |

| . | Chymotrypsin-like proteasome activity, RLU/5 μg of protein . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment . | SUDHL16 . | Percentage inhibition . | OCI-LY10 . | Percentage inhibition . |

| Control | 232 ± 2.4 | — | 198 ± 2.2 | — |

| CFZ | 26 ± 1.6 | 88 | 45 ± 2.5 | 77 |

| Vorinostat | 223 ± 1.7 | 4 | 194 ± 1.2 | 2 |

| CFZ plus vorinostat | 24 ± 1.1 | 89* | 44 ± 2.1 | 77* |

SUDHL16 cells were treated with 3.0nM CFZ with or without 0.75μM vorinostat, or OCI LY10 cells were treated with 7.0nM CFZ with or without 1.5μM vorinostat for one hour. After treatment, cells were collected, and chymotrypsin-like proteasomal activity was monitored as described in “Proteasome inhibition assays.” Values represent the mean plus or minus SD for experiments performed in triplicate on three separate occasions.

CFZ indicates carfilzomib; and —, not applicable.

Not significantly different from values for cells exposed to CFZ alone (P > .05).

Combined exposure of DLBCL cells to CFZ/vorinostat induces G2M arrest

Cell-cycle analysis was performed in SUDHL4 and OCI-LY10 cells exposed to CFZ with or without vorinostat (Table 2). Analysis excluded the subdiploid (apoptotic) cell fraction. Vorinostat by itself increased the G0-G1 population in SUDHL4 cells but had little effect on cell-cycle traverse in OCI-LY10 cells. CFZ by itself slightly increased the G2M phase population in both cell lines. However, combined treatment resulted in highly significant increases in the G2M population (P < .005 in each case), raising the possibility that this phenomenon represents a response to DNA damage (Figure 2E-F) induced by the regimen.

Cotreatment of DLBCL cells with CFZ and vorinostat induces pronounced cell cycle arrest in G2M

| Cell cycle (phase) . | Control . | CFZ . | Vorinostat . | CFZ plus vorinostat . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SUDHL4 | ||||

| G0G1 | 45.9 ± 3.8 | 31.9 ± 0.9 | 65.8 ± 1.6 | 5.9 ± 3.4 |

| G2M | 15.1 ± 1.6 | 28.2 ± 1.4* | 15.4 ± 1.2 | 78.7 ± 4.9† |

| S | 35.4 ± 2.8 | 40.4 ± 1.6 | 16.7 ± 1.3 | 15.6 ± 1.7 |

| OCI-LY10 | ||||

| G0G1 | 30.7 ± 1.7 | 23.4 ± 1.6 | 25.4 ± 3.1 | 5.9 ± 1.5 |

| G2M | 12.5 ± 1.5 | 21.8 ± 2.2* | 15.1 ± 1.7 | 50.2 ± 1.7† |

| S | 53.5 ± 4.5 | 54.7 ± 0.7 | 56.4 ± 3.1 | 44.4 ± 1.1 |

| Cell cycle (phase) . | Control . | CFZ . | Vorinostat . | CFZ plus vorinostat . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SUDHL4 | ||||

| G0G1 | 45.9 ± 3.8 | 31.9 ± 0.9 | 65.8 ± 1.6 | 5.9 ± 3.4 |

| G2M | 15.1 ± 1.6 | 28.2 ± 1.4* | 15.4 ± 1.2 | 78.7 ± 4.9† |

| S | 35.4 ± 2.8 | 40.4 ± 1.6 | 16.7 ± 1.3 | 15.6 ± 1.7 |

| OCI-LY10 | ||||

| G0G1 | 30.7 ± 1.7 | 23.4 ± 1.6 | 25.4 ± 3.1 | 5.9 ± 1.5 |

| G2M | 12.5 ± 1.5 | 21.8 ± 2.2* | 15.1 ± 1.7 | 50.2 ± 1.7† |

| S | 53.5 ± 4.5 | 54.7 ± 0.7 | 56.4 ± 3.1 | 44.4 ± 1.1 |

SUDHL4 cells were treated with 4.0nM CFZ with or without 1.5μM vorinostat, or OCI- LY10 cells were treated with 7.0nM CFZ with or without 1.5μM vorinostat for 18 hours. After treatment, cells were collected, fixed in ice-cold methanol at a ratio of 1 mL phosphate-buffered saline to 3 mL methanol, and cell-cycle traverse was analyzed by flow cytometry using Modfit software as described in “Cell-cycle analysis.”

DLBCL indicates ; and CFZ, carfilzomib.

Significantly greater than values for untreated control cells (P < .02).

Significantly greater than values for cells treated with CFZ alone (P < .005).

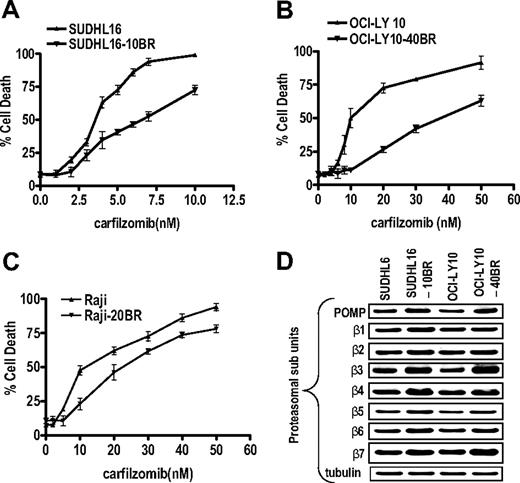

The CFZ/vorinostat regimen potently induces apoptosis in bortezomib-resistant SUDHL16 OCY-LY10 and Raji cells

To determine whether the CFZ/vorinostat regimen would be active in cells resistant to bortezomib, bortezomib-resistant SUDHL16 (SUDHL16-10BR), OCI-LY10 (OCI-LY10-40 BR), and Raji (Raji-20BR) cells were used as previously described.33 These cells are maintained in 10, 40, or 20nM bortezomib, respectively, and exhibit approximately 4- to 5-fold higher bortezomib 50% inhibitory concentration values than their control counterparts (eg, 20nM vs 4nM for SUDHL16, 45nM vs 12nM for Raji, and 40nM vs 8nM for OCI-LY10). As shown in Figure 5A through C, bortezomib-resistant SUDHL16, OCI-LY10, and, to a lesser extent, Raji cells also displayed partial cross-resistance to CFZ, but the degree of resistance was less than that observed for bortezomib. Neither resistant cell line exhibited increased expression of Pgp or resistance to conventional agents (eg, VP-16; data not shown). Consistent with previous reports of proteasome inhibitor resistance,39 both resistant DLBCL cell lines displayed increased expression of various proteasome subunits, including POMP, β3, β4, β6, and β7 (Figure 5D).

Bortezomib-resistant SUDHL16-10BR, OCI-LY10-40BR, and Raji –20BR cells exhibit partial cross-resistance to CFZ and up-regulation of proteasomal subunits. SUDHL16 and SUDHL16-10BR (A), OCI-LY10 and OCI-LY10-40BR (B), and Raji and Raji-20BR (C) cells were treated with the indicated concentration of CFZ for 36, 48, and 48 hours, respectively, after which cell death was monitored by 7-AAD staining by flow cytometry. Values represent the means for experiments performed in triplicate on 3 separate occasions plus or minus SD. (D) Logarithmically growing SUDHL16, SUDHL16-10BR, OCI-LY10, and OCI-LY10-40BR cells were harvested and proteins extracted. Western blot analysis was then performed using the indicated antibodies. Blots were stripped and reprobed with antitubulin antibodies to ensure equal loading and transfer of protein. Each lane was loaded with 20 μg of protein. Two additional experiments yielded equivalent results.

Bortezomib-resistant SUDHL16-10BR, OCI-LY10-40BR, and Raji –20BR cells exhibit partial cross-resistance to CFZ and up-regulation of proteasomal subunits. SUDHL16 and SUDHL16-10BR (A), OCI-LY10 and OCI-LY10-40BR (B), and Raji and Raji-20BR (C) cells were treated with the indicated concentration of CFZ for 36, 48, and 48 hours, respectively, after which cell death was monitored by 7-AAD staining by flow cytometry. Values represent the means for experiments performed in triplicate on 3 separate occasions plus or minus SD. (D) Logarithmically growing SUDHL16, SUDHL16-10BR, OCI-LY10, and OCI-LY10-40BR cells were harvested and proteins extracted. Western blot analysis was then performed using the indicated antibodies. Blots were stripped and reprobed with antitubulin antibodies to ensure equal loading and transfer of protein. Each lane was loaded with 20 μg of protein. Two additional experiments yielded equivalent results.

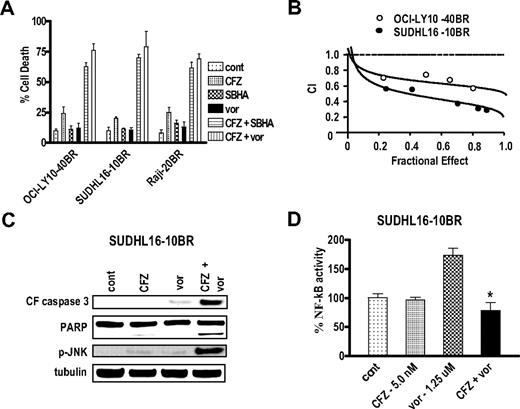

Notably, all 3 bortezomib-resistant lines exhibited a marked increase in CFZ-induced apoptosis when coincubated with subtoxic concentrations of SBHA, vorinostat (Figure 6A), or SNDX-275 (data not shown). These interactions were synergistic by median dose effect analysis with combination index values less than 1.0 (Figure 6B). Moreover, combined, but not individual, treatment of SUDHL16-10BR cells with CFZ and vorinostat induced caspase-3 cleavage, PARP degradation, and JNK activation (Figure 6C). Analogous to results involving parental cells (Figure 3A-B), CFZ prevented vorinostat-mediated NF-κB activation in SUDHL16-10BC cells (Figure 6D). Similar results were obtained in OCI-LY10 cells (data not shown). Together, these findings indicate that HDACIs increase CFZ lethality in bortezomib-resistant DLBCL cells in association with JNK activation and inhibition of NF-κB induction.

The CFZ/vorinostat regimen potently induces apoptosis in bortezomib-resistant SUDHL16-10BR, Raji 20-BR, and OCY-LY10-40BR cells. (A) OCI-LY10-40BR, Raji-20BR, and SUDHL16-10BR cells were treated with minimally toxic concentrations of CFZ and either vorinostat or SBHA for 48, 48, or 36 hours, respectively. Concentrations were as follows: (OCI-LY10-40BR) CFZ (20nM) with or without SBHA (40μM), or vorinostat (1.5μM); (Raji-20BR) CFZ (15nM) with or without SBHA (40μM) or vorinostat (2.0μM); (SUDHL16-10BR) CFZ (5nM) with or without SBHA (30μM) or vorinostat (1.25μM). Cell death was monitored by 7-AAD/DiOC6 staining and flow cytometry. (B) Fractional effect values were determined for the combination treatments, after which median dose effect analysis was used to characterize the nature of the interactions. Combination index (CI) values less than 1.0 denote a synergistic interaction. (C) SUDHL16-10 BR cells were exposed to the indicated concentrations of CFZ and vorinostat as described in panel A for 24 hours, after which Western blot analysis was performed using the indicated antibodies. Blots were stripped and reprobed with antitubulin antibodies to ensure equal loading and transfer of protein. Each lane was loaded with 20 μg of protein. Two additional experiments yielded equivalent results. (D) SUDHL16-10BR cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of CFZ and vorinostat for 24 hours. Nuclear protein was extracted using the Nuclear Extract Kit (Active Motif), and NF-κB activity was determined using an ELISA TransAM NF-κB p65 Transcription Factor Assay Kit (Active Motif), as described in “NF-κB activity.” *Significantly less than values for cells treated with vorinostat alone (P < .002). In all cases, values represent the means for experiments performed in triplicate on 3 separate occasions plus or minus SD.

The CFZ/vorinostat regimen potently induces apoptosis in bortezomib-resistant SUDHL16-10BR, Raji 20-BR, and OCY-LY10-40BR cells. (A) OCI-LY10-40BR, Raji-20BR, and SUDHL16-10BR cells were treated with minimally toxic concentrations of CFZ and either vorinostat or SBHA for 48, 48, or 36 hours, respectively. Concentrations were as follows: (OCI-LY10-40BR) CFZ (20nM) with or without SBHA (40μM), or vorinostat (1.5μM); (Raji-20BR) CFZ (15nM) with or without SBHA (40μM) or vorinostat (2.0μM); (SUDHL16-10BR) CFZ (5nM) with or without SBHA (30μM) or vorinostat (1.25μM). Cell death was monitored by 7-AAD/DiOC6 staining and flow cytometry. (B) Fractional effect values were determined for the combination treatments, after which median dose effect analysis was used to characterize the nature of the interactions. Combination index (CI) values less than 1.0 denote a synergistic interaction. (C) SUDHL16-10 BR cells were exposed to the indicated concentrations of CFZ and vorinostat as described in panel A for 24 hours, after which Western blot analysis was performed using the indicated antibodies. Blots were stripped and reprobed with antitubulin antibodies to ensure equal loading and transfer of protein. Each lane was loaded with 20 μg of protein. Two additional experiments yielded equivalent results. (D) SUDHL16-10BR cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of CFZ and vorinostat for 24 hours. Nuclear protein was extracted using the Nuclear Extract Kit (Active Motif), and NF-κB activity was determined using an ELISA TransAM NF-κB p65 Transcription Factor Assay Kit (Active Motif), as described in “NF-κB activity.” *Significantly less than values for cells treated with vorinostat alone (P < .002). In all cases, values represent the means for experiments performed in triplicate on 3 separate occasions plus or minus SD.

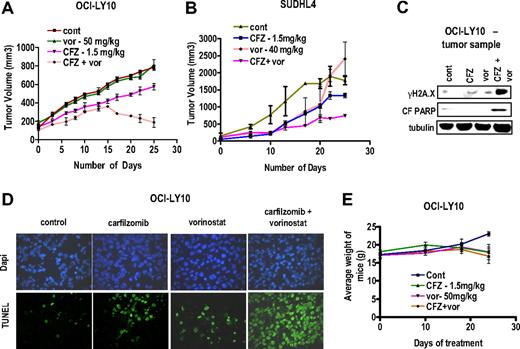

Vorinostat increases CFZ-mediated DNA damage, apoptosis, and tumor growth suppression in an in vivo OCI-LY10 and SUDHL4 model

To determine whether similar interactions between CFZ and vorinostat occurred in vivo, NIH-II (Beige) mice were inoculated in the flank with 10 × 106 OCI-LY10 (ABC subtype) or SUDHL4 (GC subtype) DLBCL cells, and after the formation of tumors (10-14 days for OCI-Ly10 cells and 14-21 days for SUDHL4 cells), treated with CFZ 1.5 mg/kg with or without vorinostat 40 to 50 mg/kg administered concurrently BIW as described in “Animal studies.” As shown in Figure 7A-B, vorinostat by itself had little effect on tumor growth at day 25, whereas CFZ by itself modestly decreased tumor size. However combined treatment with CFZ and vorinostat resulted in significant tumor growth suppression compared with single-agent treatment. Western blot analysis of excised tumor tissue revealed that combined, but not individual, drug treatment resulted in a striking increase in γH2A.X expression and PARP cleavage (Figure 7C). TUNEL staining of tissue sections revealed that, whereas vorinostat had little effect and CFZ alone increased TUNEL positivity modestly, combined treatment resulted in a pronounced increase in TUNEL staining (Figure 7D). Lastly, body weights of mice exposed to different treatment regimens were monitored (Figure 7E) and revealed only marginal weight loss (eg, < 10%) for mice exposed to both agents. These findings indicate that HDACIs increase the in vivo as well as the in vitro activity of CFZ in DLBCL cells.

Vorinostat potentiates CFZ-mediated DNA damage, apoptosis, and tumor growth suppression in an in vivo OCI-LY10 xenograft model. NIH-III nude mice were injected in the flank with (A) 10 × 106 OCI-LY10 cells or (B) 10 × 106 SUDHL4 cells and treated with the indicated doses CFZ with or without vorinostat twice weekly on days 1 and 2 as described in “Animal studies.” Tumor volumes were measured twice every week, and mean tumor volume was plotted against days of treatment. (C) Tumor samples were extracted from mice and lysed with lysis buffer followed by sonication. Western blotting was performed using the extracted proteins, which were then probed with the indicated primary antibodies. Each lane was loaded with 20 μg of protein; blots were subsequently stripped and reprobed with antibodies to tubulin to ensure equivalent loading and transfer. (D) Tumor samples were extracted after the 25th day of treatment and fixed to slides as described in “TUNEL assays of tissue sections.” TUNEL assays were performed on the fixed cells, which were also counterstained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. Photomicrographs were obtained with an Olympus fluorescence microscope (original magnification ×20). (E) Weights of each mouse after various treatment regimens were monitored weekly, and the mean weight of each group was plotted against days of treatment.

Vorinostat potentiates CFZ-mediated DNA damage, apoptosis, and tumor growth suppression in an in vivo OCI-LY10 xenograft model. NIH-III nude mice were injected in the flank with (A) 10 × 106 OCI-LY10 cells or (B) 10 × 106 SUDHL4 cells and treated with the indicated doses CFZ with or without vorinostat twice weekly on days 1 and 2 as described in “Animal studies.” Tumor volumes were measured twice every week, and mean tumor volume was plotted against days of treatment. (C) Tumor samples were extracted from mice and lysed with lysis buffer followed by sonication. Western blotting was performed using the extracted proteins, which were then probed with the indicated primary antibodies. Each lane was loaded with 20 μg of protein; blots were subsequently stripped and reprobed with antibodies to tubulin to ensure equivalent loading and transfer. (D) Tumor samples were extracted after the 25th day of treatment and fixed to slides as described in “TUNEL assays of tissue sections.” TUNEL assays were performed on the fixed cells, which were also counterstained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. Photomicrographs were obtained with an Olympus fluorescence microscope (original magnification ×20). (E) Weights of each mouse after various treatment regimens were monitored weekly, and the mean weight of each group was plotted against days of treatment.

Discussion

The results of the present study indicate that the activity of CFZ, a second-generation irreversible proteasome inhibitor, is dramatically potentiated by HDACIs in DLBCL cells, including both ABC- and GC-type DLBCL. ABC-DLBCL is characterized by increased dependence on the NF-κB pathway and poorer overall survival than its GC-DLBCL counterpart.4,5 Although the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib has shown very limited single-agent activity in DLBCL, results of a recent study suggest that addition of bortezomib to standard chemotherapy improves outcomes in ABC-DLBCL.25 Such findings are consistent with evidence that bortezomib kills cells through inhibition of NF-κB, on which ABC-DLBCL cells are presumably dependent.4,5 In addition, it has been proposed that synergistic interactions between HDAC and proteasome inhibitors in malignant hematopoietic cells reflect inhibition of HDACI-mediated NF-κB activation,29,30 a phenomenon that may stem from RelA acetylation.36 However, it is noteworthy that HDACIs blocked NF-κB activation and promoted CFZ lethality in both ABC- and GC-type DLBCL cells, arguing against the possibility that this interaction is specific for NF-κB–addicted cells. In addition, there is evidence that proteasome inhibitor lethality may involve factors other than NF-κB inhibition18,19 ; and in a recent study involving myeloma cells, bortezomib was unexpectedly shown to activate NF-κB.40 Consequently, the possibility that HDACIs potentiate CFZ through mechanisms unrelated to NF-κB cannot be excluded.

Aside from disruption of NF-κB activation by proteasome inhibitors, synergistic interactions between such agents have been attributed to disruption of aggresome function and induction of ER stress.19,31 HDACIs, particularly class IIb inhibitors, which inhibit HDAC6 and acetylate tubulin, have been shown to interfere with the dynein motor and to disrupt aggresome function.41 Furthermore, combining such agents with proteasome inhibitors, which block protein degradation, may result in lethal ER stress.31 However, synergistic interactions were observed between CFZ and SNDX-275, which is considered to be primarily an inhibitor of class I HDACs. In addition, increased evidence of the unfolded protein response in cells exposed to both HDACIs and CFZ was not observed. Although such findings do not rule out the possible contribution of ER stress to HDACI/CFZ lethality, they suggest that other mechanisms are probably operative in this setting.

It is noteworthy that combined exposure of DLBCL cells to CFZ and HDACIs resulted in a marked increase in DNA damage, reflected by increased expression of γH2A.X, a marker of double-strand DNA breaks,38 as well as increased activation of the JNK stress-related signaling pathway. Recent studies have highlighted the ability of HDACIs, in addition to their other actions, to induce DNA damage in transformed cells and to promote γH2A.X formation, which participates in DNA damage repair.42 Similarly, the ubiquitin-proteasome system also plays a key role in DNA repair,43 and proteasome inhibitors, such as bortezomib, are known to disrupt this process.44 Consequently, CFZ and HDACIs may cooperate to promote DNA damage, thereby contributing to cell death. In this context, the JNK-related stress pathway is classically activated by DNA damage,45 and JNK phosphorylation has been described in multiple myeloma cells exposed to lethal concentrations of CFZ.26 The finding that pharmacologic or genetic interruption of JNK signaling attenuated CFZ/HDACI lethality indicates that this pathway plays a significant functional role in cell death induction. Finally, it is possible that the pronounced increase in G2M arrest observed in CFZ/HDACI-treated cells represents a consequence of enhanced DNA damage.46

CFZ/HDACI regimens effectively induced cell death in DLBCL cells (including primary cells) in vitro and in vivo but displayed relatively modest lethality toward normal hematopoietic cells or toxicity in intact animals. In this regard, both proteasome and HDACIs, administered individually, have shown selective toxicity toward transformed cells.21,47 Although the mechanisms underlying the selectivity of these agents remain to be definitively established, the present findings raise the possibility that regimens combining CFZ with HDACIs may also preferentially target neoplastic versus normal cells.

It is important to note that the CFZ/vorinostat regimen was fully capable of inducing apoptosis in both ABC- and GC-DLBCL cells resistant to bortezomib. Analogous to results reported in myeloma cells,26 bortezomib-resistant DLBCL cells displayed some resistance to CFZ, but the degree of resistance was clearly less than that exhibited toward bortezomib. Significantly, when vorinostat was combined with CFZ, the extent of cell death was equivalent in bortezomib-sensitive and -resistant cells, suggesting that HDACIs can overcome partial cross-resistance of the latter cells to CFZ. The mechanisms by which cells become resistant to proteasome inhibitors are not known with certainty but may include drug efflux processes. However, the failure to detect increased Pgp expression and the lack of cross-resistance to efflux pump substrates (eg, VP-16) in resistant DLBCL cells would argue against this possibility. Consistent with the results of earlier studies involving other malignant cell types (eg, leukemia),39 bortezomib-resistant DLBCL cells displayed increased expression of various proteasome subunits (eg, β2, β5, and β7 among others). In addition, HDACIs have been shown to inhibit proteasome function in myeloma cells,13 and cooperative interactions between proteasome and HDAC inhibitors have recently been related to down-regulation of the proteasomal cargo protein HR23B.13 In contrast, coadministration of CFZ and HDACIs did not result in enhanced inhibition of chymotryptic activity, an important determinant of CFZ lethality in multiple myeloma and other malignant hematopoietic cells,17,26 nor was a decline in HR23B levels observed (G.D., S.G., unpublished observations, July 2009). However, the possibility that more pronounced inhibition of immunoproteasome activity, which has recently been shown to be inhibited by CFZ in multiple myeloma cells,48,49 contributes to CFZ/HDACI lethality in bortezomib-resistant DLBCL cells cannot be excluded. Finally, the ability of vorinostat to potentiate CFZ-induced JNK activation in bortezomib-resistant DLBCL cells supports the notion that this stress kinase plays a role in overcoming resistance by HDACI/CFZ regimens.

Consistent with the marked increase in cell death observed in vitro, combined treatment with CFZ and vorinostat resulted in a pronounced reduction in tumor growth in nude mice bearing ABC-type OCI-LY10 or GC-type SUDHL4 cells. This finding may have particular significance in view of the generally poor chemoresponsiveness of ABC-DLBCL.4,5 In earlier studies, higher CFZ doses (eg, 3-5 mg/kg BIW) markedly suppressed the in vivo growth of colon tumor cells.17 Notably, low doses of CFZ alone (eg, 1.5 mg/kg BIW), administered according to the same schedule, moderately suppressed OCI-LY10 and SUDHL4 tumor growth in association with apoptosis induction. However, coadministration of vorinostat at a dose that by itself had little or no effect on cell death or tumor size markedly increased apoptosis and suppressed tumor growth. Whether CFZ will display single-agent activity in ABC- or GC-DLBCL, in contrast to bortezomib,24,25 remains to be determined. Although single-agent vorinostat has shown preliminary evidence of activity in follicular lymphoma, its effectiveness in DLBCL has yet to be demonstrated.16 Consequently, the ability of subeffective vorinostat doses and schedules to potentiate CFZ activity in ABC-DLBCL cells in vivo takes on added significance. Such findings, along with the observation that CFZ/HDACI regimens display significant activity in bortezomib-resistant DLBCL cells, and are active against primary cells, argue that a dual strategy combining second-generation proteasome inhibitors with HDACIs warrants further consideration in DLBCL. Accordingly, plans to develop CFZ/HDACI regimens for the treatment of DLBCL are currently under way.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (awards CA63753, CA93738, and CA100866), the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society of America (award R6059-06), the Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation, the V Foundation, and Lymphoma SPORE (award 1P50 CA130805).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: G.D. designed and performed the research, collected, analyzed, and compiled data, and helped write the manuscript; D.L. performed the research and collected, analyzed, and compiled data; L.K. helped perform the research; R.F., J.F., and P.D. helped design the research and write the manuscript; and S.G. supervised the research and helped write the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Steven Grant, Department of Medicine and Biochemistry, Division of Hematology/Oncology, Virginia Commonwealth University/Medical College of Virginia, MCV Station Box 230, Richmond, VA 23298; e-mail: stgrant@vcu.edu.