To the editor:

Capillary leak syndrome (CLS) is a severe complication of allogeneic stem cell transplantation (SCT) characterized by weight gain, generalized edema, hypotension, and hypoalbuminemia.1 The main CLS pathogenesis is injury of the capillary endothelium resulting in a loss of intravascular fluid into interstitial spaces. Treatment is limited to withdrawal of growth factors and systemic corticosteroids; however, a good response is limited and most severe CLS cases progress to fatal multiple-organ dysfunction syndrome. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is a potent inducer of vascular permeability and may have a crucial role in the mechanism underlying CLS formation.2 In the present study, we report the successful treatment of life-threatening CLS that developed after allogeneic SCT using the anti-VEGF antibody bevacizumab (Avastin; Chugai).3

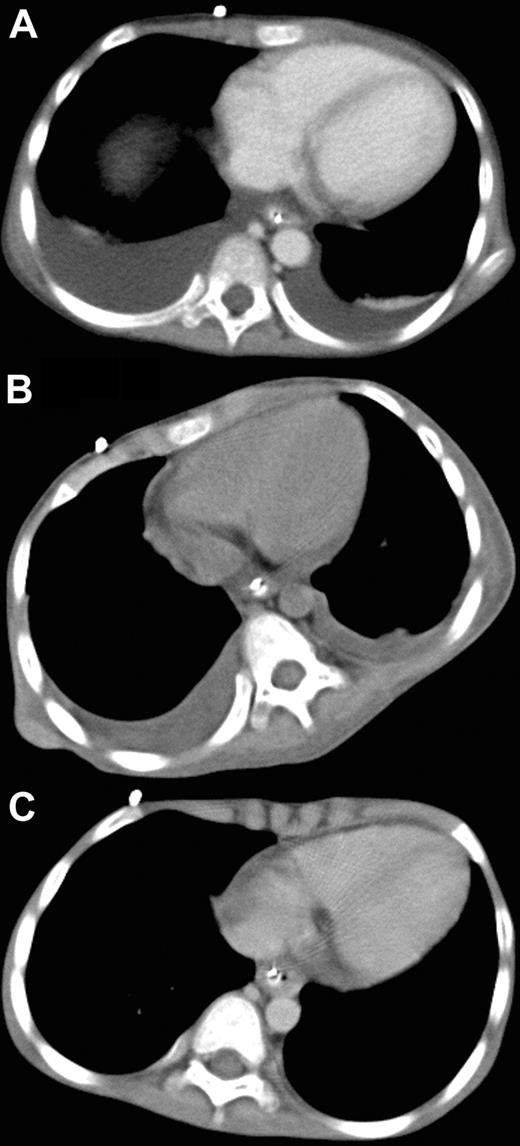

A 6-year-old male with Fanconi anemia received marrow cells from a HLA–DRB1 mismatched unrelated donor as previously described.4 On day 22 after SCT, the patient developed posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome with mild systemic edema, suggesting generalized injury of the vascular endothelium. Subsequently, grade 2 acute graft-versus-host disease of the skin and gastrointestinal tract ensued but was easily controlled with prednisolone. However, systemic edema accompanying consciousness disturbance, tachypnea and tachycardia developed 68 days after SCT. Computed tomography (CT) revealed massive pleural effusion (Figure 1A) and ascites, and the patient was diagnosed with CLS. Despite intensive conventional treatments, including prednisolone (1 mg/kg daily), ulinastatin (10 000 units/kg daily), and albumin (0.8 g/kg every other day), hypotension, negative central venous pressure, and anuria developed 72 days after SCT. Because of the patient's critical condition and lack of response to other therapies, his case was discussed in the transplantation peer review group. Off-label use of bevacizumab was recommended. Written informed consent to the treatment in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and permission to publish results were obtained from the parents separately before the study and after the study, respectively. The publication of this study involving bevacizumab administration was approved by the institutional review board of Tokai University Hospital. Rationale and potential side effects were also discussed with the parents. Intravenous bevacizumab (5 mg/kg body weight) was administered over a 90-minute period. On the first day after treatment, urine production started to improve, and blood pressure and central venous pressure returned to the normal range. On the second day, all symptoms were ameliorated. A marked decrease in the amounts of pleural effusion was evident on the CT films obtained on the fifth day after bevacizumab administration (Figure 1B), and complete resolution of pleural effusion was revealed on the CT films taken 20 days after the treatment (Figure 1C). Plasma VEGF level before bevacizumab administration was not elevated (27 pg/mL; normal, < 115 pg/mL).

Administration of bevacizumab. Chest CT before (A), 5 days after (B), and 20 days after (C) treatment with bevacizumab.

Administration of bevacizumab. Chest CT before (A), 5 days after (B), and 20 days after (C) treatment with bevacizumab.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on bevacizumab treatment of CLS developing after SCT. CLS after SCT has been difficult to ameliorate; however, bevacizumab was shown to be highly effective against CLS in a patient even when plasma VEGF level was not increased, and may be useful under coexisting illness after SCT. Vascular endothelial damage plays a causal role in early complications of vascular origin after SCT, including hepatic veno-occlusive disease, engraftment syndrome, thrombotic microangiopathy, and idiopathic pneumonia syndrome.5 Bevacizumab may have a broad spectrum of efficacy against these complications.

Authorship

Contribution: H.Y. designed the study and wrote the paper; M.Y. performed diagnosis and planned treatment; T.K., T.S., and T.M. were substantially involved in clinical management; and S.K. performed real-time PCR and chimerism analysis.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Dr Hiromasa Yabe, Department of Cell Transplantation and Regenerative Medicine, Tokai University School of Medicine, 143 Shimokasuya, Isehara, Kanagawa, 259-1193, Japan; e-mail: yabeh@is.icc.u-tokai.ac.jp.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal