Myeloma bone disease is caused by uncoupling of osteoclastic bone resorption and osteoblastic bone formation. Bidirectional signaling between the cell-surface ligand ephrinB2 and its receptor, EphB4, is involved in the coupling of osteoblastogenesis and osteoclastogenesis and in angiogenesis. EphrinB2 and EphB4 expression in mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) from myeloma patients and in bone cells in myelomatous bones was lower than in healthy counterparts. Wnt3a induced up-regulation of EphB4 in patient MSCs. Myeloma cells reduced expression of these genes in MSCs, whereas in vivo myeloma cell-conditioned media reduced EphB4 expression in bone. In osteoclast precursors, EphB4-Fc induced ephrinB2 phosphorylation with subsequent inhibition of NFATc1 and differentiation. In MSCs, EphB4-Fc did not induce ephrinB2 phosphorylation, whereas ephrinB2-Fc induced EphB4 phosphorylation and osteogenic differentiation. EphB4-Fc treatment of myelomatous SCID-hu mice inhibited myeloma growth, osteoclastosis, and angiogenesis and stimulated osteoblastogenesis and bone formation, whereas ephrinB2-Fc stimulated angiogenesis, osteoblastogenesis, and bone formation but had no effect on osteoclastogenesis and myeloma growth. These chimeric proteins had similar effects on normal bone. Myeloma cells expressed low to undetectable ephrinB2 and EphB4 and did not respond to the chimeric proteins. The ephrinB2/EphB4 axis is dysregulated in MM, and its activation by EphB4-Fc inhibits myeloma growth and bone disease.

Introduction

The coupling of bone resorption to bone formation is tightly controlled through communication between osteogenic cells and osteoclasts via cell surface and systemic factors.1 In multiple myeloma (MM), the coupling of osteoclastic bone resorption and osteoblastic bone formation is disrupted, resulting in severe osteolytic bone disease.2 Whereas bone resorption is stimulated by increased production of osteoclast-stimulating factors,3,,,–7 bone formation is suppressed by osteoblastogenic inhibitors.8,9 Osteolytic lesions in MM often occur in areas adjacent to the tumor area,10 suggesting that, in addition to soluble factors, cell surface factors mediating coupling of bone remodeling are dysregulated in this disease

Eph receptors and ephrin ligands are cell-surface molecules capable of bidirectional signaling that control cell-cell interactions, immune regulation, neuronal development, tumor growth, metastasis, and angiogenesis.11 Recent studies indicate that bidirectional signaling between the ligand ephrinB2 and its receptor, EphB4, also mediates communication between osteoblasts and osteoclasts.12,–14 Although mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and osteoblasts express ephrinB2 and EphB4, osteoclasts mainly express ephrinB2. Forward signaling in MSCs promotes osteogenic differentiation, and reverse signaling in osteoclast precursors inhibits their differentiation.13 It has been proposed that signaling through this axis regulates osteoblastogenesis also via an autocrine or paracrine loop.14

Although the consequences of inhibition of osteoclast activity on MM bone disease and tumor progression have been intensively documented and recognized,15 recent experimental studies indicate that osteoblast-activating agents, such as anti-DKK1,16 Wnt3a,17 and lithium chloride,18 prevent MM-induced bone disease and inhibit myeloma growth through alteration of the bone marrow (BM) microenvironment. The aims of our study were to shed light on the involvement of the ephrinB2/EphB4 axis in MM bone disease and the consequences of activating forward or reverse signaling with ephrinB2-Fc or EphB4-Fc, respectively, on osteoblast and osteoclast differentiation. We also aimed to test the effect of the ephrinB2-Fc or EphB4-Fc on myeloma growth and bone disease in myelomatous bones and on bone parameters in normal bone using the well-established SCID-hu system.19

Methods

BM samples and patient characteristics

MSCs were prepared from the BM of previously untreated MM patients (n = 13) and healthy donors (n = 5). University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Institutional Review Board-approved informed consents were obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the forms kept on record. Patient characteristics are described in supplemental Table 1 (available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). Ten of the 13 MM patients had detectable MRI focal lesions. BM mononucleate cells from healthy donors were obtained from Lonza Walkersville. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and global gene expression profiling (GEP) were performed as described previously.20,21

MSCs

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) were prepared as previously described.22 Briefly, BM mononucleate cells (2 × 106 cells/mL) from patients with MM and from healthy donors were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM), low glucose (DMEM-LG), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics (MSC medium). One-half of the medium was replaced every 4 to 6 days, and adherent cells were allowed to reach 80% confluence before they were subcultured with trypsin-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid. GEP revealed that patient and donor MSCs did not express hematopoietic markers, such as CD38, CD45, or CD14, and had similar expression of MSC (eg, CD166) or bone (eg, ALP and RUNX2) markers (S.Y., unpublished data, October 2008). Growth of our luciferase-expressing myeloma cell lines and cocultures with MSCs was preformed as described.23 In indicated experiments, MSCs or osteoblasts generated from MSCs were cocultured with myeloma cells using transwell inserts with 3-μm pores as previously described.22

Immunohistochemistry

MSCs were cultured in 4-well chamber slides (LAB-TEK). The slides were fixed with HistoChoice (aMRESCO) followed by antigen retrieval using a water bath at 80°C for 25 minutes. After peroxidase quenching with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 5 minutes, sections were reacted with rabbit anti–human ephrinB2 (20 μg/mL; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), mouse anti-EphB4 receptor (50 μg/mL, Invitrogen), and IgG (Dako North America) antibodies for 60 minutes; the assay was completed with the use of Dako's immunoperoxidase kit. Sections were lightly counterstained with hematoxylin. An Olympus BH2 microscope (Olympus) was used to obtain images with a SPOT 2 digital camera (Diagnostic Instruments). Adobe Photoshop, Version 10 (Adobe Systems), was used to process the images.

EphrinB2 flow cytometry

MSCs were trypsinized and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in 37°C for 10 minutes followed by incubation in 90% methanol on ice for 30 minutes. MSCs were then incubated with primary rabbit anti–human ephribB2 or rabbit anti-IgG antibodies (20 μg/mL, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 60 minutes, washed 3 times with flow cytometry buffer (0.5% bovine serum albumin in phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]), and incubated with a secondary AlexaFluor 488 F(ab′)2 fragment of goat anti–rabbit antibody (2 μg/mL, Invitrogen) for 30 minutes. At the end of the incubation period, MSCs were washed and resuspended in flow cytometry buffer and thereafter assayed on the FACScan cytometer. The data were quantified by dividing the mean florescence intensity of ephrinB2-stained MSCs by the mean of control IgG antibody-stained MSCs.

For technical reasons, we have not performed flow cytometry analysis for EphB4; instead, we used a commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit to determine levels of EphB4 protein in cell lysate.

Total and phosphorylated EphB4 ELISA

Fc, EphB4-Fc, and ephrinB2-Fc were obtained from R&D Systems. Clustered EphB4-Fc or ephrinB2-Fc was prepared by preincubation of each chimeric protein with Fc at a 10:1 ratio for one hour at room temperature.

Steady-state levels of total EphB4 were determined in MSCs cultured in serum-containing media. For testing levels of phosphorylated EphB4, MSCs were starved overnight in serum-free media before stimulation with ephrinB2-Fc (4 μg/mL) for 20 minutes.

MSCs were washed with PBS, and protein extraction was performed using R&D Systems lysis buffer. Protein concentration was quantified by bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce Chemical) to assure a uniform content among all samples. Measurement of total or phosphorylated EphB4 levels in 50 to 100 μg of protein extracts was performed using a sandwich ELISA kit (R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Western blot

MSCs were starved overnight in serum-free DMEM before stimulation with EphB4-Fc (2 μg/mL) for 20 minutes. Osteoclasts were used as positive control. Cells were washed with Tris-buffered saline Na orthovanadate, and protein extraction was performed using lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 5 μg/mL leupeptin, 2 μg/mL aprotinin, 10 mM NaF, 1 mM Na orthovanadate, 1% Triton X100, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). Protein concentration was quantified by bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce Chemical).

Phosphorylation status of ephrinB2 was analyzed by immunoblotting. Lysates were separated by electrophoresis on 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels, and Western blotting was carried out according to the Western Breeze chemiluminescent immunodetection protocol as described by the manufacturer (Invitrogen). The following primary antibodies were used: ephrinB (Invitrogen), phosphorylated ephrinB, and β-actin (Cell Signaling Technology).

Animal study

SCID-hu mice were constructed as previously described.19 The mice were housed and monitored in our animal facility. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences approved all experimental procedures and protocols. Myeloma cells (2 × 106 plasma cells diluted in 100 μL PBS) from a patient with active MM and detectable bone disease were inoculated into the implanted bone of 20 SCID-hu mice. Mice were periodically bled from the tail vein, and changes in levels of circulating human light chain immunoglobulin (hIg) of the M-protein isotype were used as an indicator of tumor growth. Sixteen of the 20 hosts were successfully engrafted with MM. Hosts were randomized into 3 groups (5 mice/group) and locally treated with Fc (control), ephrinB2-Fc, or EphB4-Fc for 4 weeks using an Alzet pump that continuously released each compound at a rate of 0.11 μg/hour directly into the implanted bone.17 The effect of MM and treatment on bone disease was assessed radiographically and through measurement of bone mineral density (BMD) before initiation of treatment and at the conclusion of the experiment. Static histomorphometry and analysis of tumor area in the implanted bone marrow were assessed on bone sections stained for hematoxylin and eosin using Osteometrics software. Histomorphometry and evaluation of numbers of osteoblasts, osteoclasts, and neovessels were performed as described previously.17,24,–26 In an additional experiment, nonmyelomatous SCID-hu hosts were similarly treated with the chimeric proteins (5 mice/group) for 4 weeks.

To analyze the effect of myeloma cell-conditioned media on expression of EFNB2 and EPHB4 in vivo, conditioned media were collected from cultures of the U266 stroma-independent cell line (ATCC), the stroma-dependent CF cell line,23 and from patient CD138-selected myeloma plasma cells (2 × 106 cells/mL, 36 hours). Conditioned or control media were injected (100 μL/injection) twice a day for 3 days into the surrounding area of the implanted human bone in SCID-hu mice. Five hosts were treated with each conditioned media. At the end of the experiment, RNA was extracted from the implanted whole human bones and subjected to quantitative RT-PCR analysis.

Osteoclast differentiation and NFATc1 expression

Human osteoclasts were prepared from peripheral blood mononuclear cells as previously described.27 Briefly, peripheral blood mononuclear cells were cultured at 2.5 × 106 cells/mL in osteoclast medium containing α-minimum essential medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 50 ng/mL receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (PeproTech), and 25 ng/mL macrophage colony-stimulating factor (PeproTech). After allowing adherence for approximately 36 hours, the adherent cells were treated with Fc or EphB4-Fc (4 μg/mL). NFATc1 expression was determined by quantitative RT-PCR after 48 hours of treatment. Osteoclast differentiation was determined 7 to 10 days after initiation of treatment by fixing, staining for TRAP, and counting the number of TRAP-expressing multinucleated osteoclasts as described.27

Osteocalcin expression and calcium deposition in differentiating MSCs

Donor and patient MSCs were cultured in osteogenic media containing 100 nM dexamethasone, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, and 0.05 mM ascorbate22 and treated with Fc or clustered ephrinB2-Fc (4 μg/mL). At indicated times, the cultures were fixed and immunohistochemically stained for osteocalcin or for detection of calcium deposition by von Kossa staining as previously described.22,25,26

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were determined using the unpaired Student t test. Values are expressed as mean plus or minus SEM.

Results

EphrinB2 and EphB4 are underexpressed in MSCs from MM patients and in bone cells in myelomatous bone

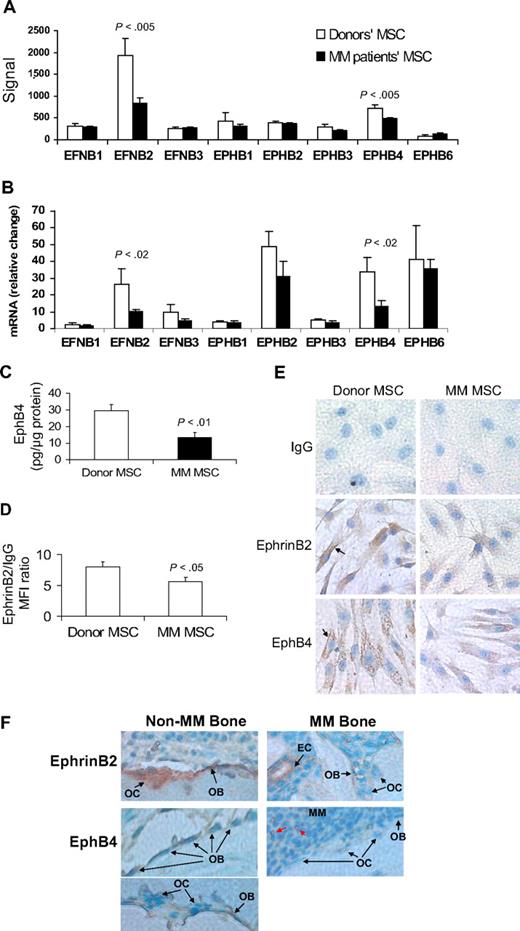

All tested ephrin and EphB family members were expressed in patient and donor MSCs (Figure 1A-B). However, expression levels of EFNB2 (encoding ephrinB2) and EPHB4 were significantly reduced in patient MSCs by GEP and quantitative RT-PCR analyses (Figure 1B). Protein analysis, by ELISA or flow cytometry, and immunohistochemical staining revealed reduced levels of ephrinB2 and EphB4 in patient MSCs (Figure 1C-E). We also sought to test the effects on expression of EFNB2 and EPHB4 after treatment of MSCs with Wnt3a, which has been shown to impact bone formation in myelomatous bones.17 Short-term exposure of MM patient MSCs to Wnt3a induced up-regulation of EPHB4 but elicited no change in expression of EFNB2, suggesting that EPHB4 is a Wnt-signaling target gene (supplemental Figure 1).

EphrinB2 (EFNB2) and EphB4 (EPHB4) are down-regulated in MM MSCs and in osteoblasts and osteoclasts in myelomatous bones. (A-B) Gene expression of the B family of ephrin ligand and Eph receptor genes in MSCs from MM patients (n = 13) and healthy donors (n = 5) analyzed by GEP (A) and quantitative RT-PCR (B). Note down-regulation of EFNB2 and EPHB4 in MM patient MSCs. (C) Protein level of EphB4 as determined by ELISA, demonstrating reduced total amount of this receptor in patient MSCs. (D) Protein level of ephrinB2 as determined by flow cytometry analysis, demonstrating reduced mean florescent intensity of this ligand in patient MSCs. (E) Representative immunohistochemical analysis revealed reduced levels of ephrinB2 and EphB4 in patient MSCs (original magnification ×200). Note cell surface (↑) and cytoplasmic expression (stained brown) of these factors. (F) Bone sections from myelomatous (MM Bone) and nonmyelomatous (Non-MM Bone) human bones in SCID-hu mice were immunohistochemically stained for human EphB4 and ephrinB2. Note strong expression of EphB4 in osteoblasts in nonmyelomatous bones (bottom left panel), whereas myelomatous bones contained fewer osteoblasts that expressed very low levels of EphB4 (bottom right panel). Osteoclasts (OC) did not appear to express EphB4, whereas hematopoietic cells that seem to be of monocytic lineage (red arrows) highly expressed EphB4 and served as an internal positive control. Also note that ephrinB2 was evident in osteoclasts and osteoblasts in nonmyelomatous bones (top left panel), whereas in myelomatous bones low expression of ephrinB2 was detected in osteoclasts and osteoblasts (top right panel). Vascular endothelial cells (EC) expressed high levels of ephrinB2 in myelomatous bones and served as an internal positive control. An Olympus BH2 microscope equipped with a 160×/0.17 numerical aperture objective (Olympus) was used to obtain images with a SPOT 2 digital camera (Diagnostic Instruments).

EphrinB2 (EFNB2) and EphB4 (EPHB4) are down-regulated in MM MSCs and in osteoblasts and osteoclasts in myelomatous bones. (A-B) Gene expression of the B family of ephrin ligand and Eph receptor genes in MSCs from MM patients (n = 13) and healthy donors (n = 5) analyzed by GEP (A) and quantitative RT-PCR (B). Note down-regulation of EFNB2 and EPHB4 in MM patient MSCs. (C) Protein level of EphB4 as determined by ELISA, demonstrating reduced total amount of this receptor in patient MSCs. (D) Protein level of ephrinB2 as determined by flow cytometry analysis, demonstrating reduced mean florescent intensity of this ligand in patient MSCs. (E) Representative immunohistochemical analysis revealed reduced levels of ephrinB2 and EphB4 in patient MSCs (original magnification ×200). Note cell surface (↑) and cytoplasmic expression (stained brown) of these factors. (F) Bone sections from myelomatous (MM Bone) and nonmyelomatous (Non-MM Bone) human bones in SCID-hu mice were immunohistochemically stained for human EphB4 and ephrinB2. Note strong expression of EphB4 in osteoblasts in nonmyelomatous bones (bottom left panel), whereas myelomatous bones contained fewer osteoblasts that expressed very low levels of EphB4 (bottom right panel). Osteoclasts (OC) did not appear to express EphB4, whereas hematopoietic cells that seem to be of monocytic lineage (red arrows) highly expressed EphB4 and served as an internal positive control. Also note that ephrinB2 was evident in osteoclasts and osteoblasts in nonmyelomatous bones (top left panel), whereas in myelomatous bones low expression of ephrinB2 was detected in osteoclasts and osteoblasts (top right panel). Vascular endothelial cells (EC) expressed high levels of ephrinB2 in myelomatous bones and served as an internal positive control. An Olympus BH2 microscope equipped with a 160×/0.17 numerical aperture objective (Olympus) was used to obtain images with a SPOT 2 digital camera (Diagnostic Instruments).

In vivo, human bone sections from SCID-hu mice engrafted with primary myeloma cells (see “EphrinB2-Fa and EphB4-Fc affect bone parameters, osteoclastogenesis, osteoblastogenesis, and tumor growth in myelogenous bone”) were immunohistochemically stained for human ephrinB2 and EphB4. The analysis revealed reduced expression of these molecules in osteoblasts and osteoclasts in bone areas highly infiltrated with MM (Figure 1F).

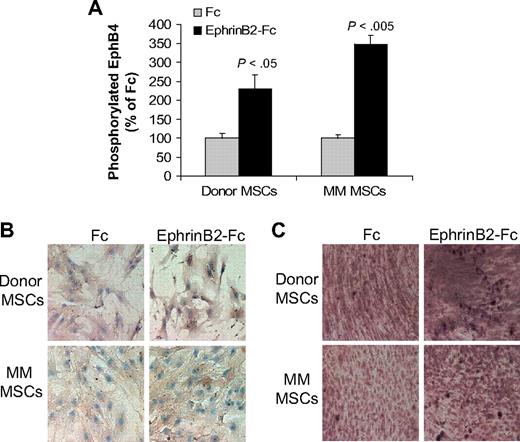

EphrinB2-Fc induces forward signaling in MSCs

The ephrinB2-Fc chimeric protein has been shown to induce forward signaling via EphB4 in murine calvarial osteoblasts.13 We tested the ability of ephrinB2-Fc to induce forward signaling through EphB4 and downstream effectors in cultured donor or MM patient MSCs. EphrinB2-Fc induced phosphorylation of EphB4 in both donor and patient MSCs (Figure 2A). We further tested the effect of ephrinB2-Fc on expression of osteocalcin, a downstream EphB4 target gene,13 and on calcium deposition in differentiating MSCs. EphrinB2-Fc markedly increased osteocalcin expression and calcium deposition in donor MSCs (Figure 2B-C). In contrast, moderate up-regulation of osteocalcin expression and calcium deposition was detected in patient MSCs after treatment with ephrinB2-Fc (Figure 2B-C). These results suggest that, although patient MSCs can signal through EphB4, their osteogenic potential is impaired compared with normal MSCs.

EphrinB2-Fc induces forward signaling in MSCs. (A) Donor and patient MSCs were starved overnight and stimulated with clustered ephrinB2-Fc (4 μg/mL) for 20 minutes before being assayed for phosphorylated EphB4 using ELISA. Note induction of EphB4 phosphorylation by ephrinB2 in donor and patient MSCs. (B) Donor and patient MSCs cultured in osteogenic media were treated with Fc or clustered ephrinB2-Fc (4 μg/mL) for 5 days and then subjected to immunohistochemical staining for osteocalcin. Note that, although ephrinB2-Fc increased expression of osteocalcin in both types of MSCs, the effect of the chimeric protein on osteoblast differentiation (mineralization) was more profound in donor MSCs. (C) Accumulation of calcium as determined by von Kossa staining (brown) in MSCs treated with Fc or ephrinB2-Fc for 10 days. Note increased calcium deposition by ephrinB2-Fc in both types of MSCs and stronger staining in donor MSCs than patient MSCs. Similar results were obtained in MSCs from 3 donors and patients with MM.

EphrinB2-Fc induces forward signaling in MSCs. (A) Donor and patient MSCs were starved overnight and stimulated with clustered ephrinB2-Fc (4 μg/mL) for 20 minutes before being assayed for phosphorylated EphB4 using ELISA. Note induction of EphB4 phosphorylation by ephrinB2 in donor and patient MSCs. (B) Donor and patient MSCs cultured in osteogenic media were treated with Fc or clustered ephrinB2-Fc (4 μg/mL) for 5 days and then subjected to immunohistochemical staining for osteocalcin. Note that, although ephrinB2-Fc increased expression of osteocalcin in both types of MSCs, the effect of the chimeric protein on osteoblast differentiation (mineralization) was more profound in donor MSCs. (C) Accumulation of calcium as determined by von Kossa staining (brown) in MSCs treated with Fc or ephrinB2-Fc for 10 days. Note increased calcium deposition by ephrinB2-Fc in both types of MSCs and stronger staining in donor MSCs than patient MSCs. Similar results were obtained in MSCs from 3 donors and patients with MM.

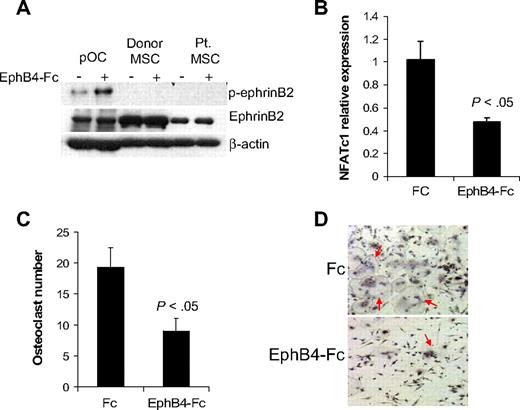

EphB4-Fc induces reverse signaling in osteoclast precursors but not in MSCs

EphB4-Fc has been shown to induce reverse signaling through ephrinB2 in murine osteoclast precursors,13 whereas induction of such reverse signaling in osteoprogenitors is uncertain. It has been shown that ephrinB2 can interact with all EphB receptors, but only EphB4 can stimulate reverse signaling through ephrinB2.11 We confirmed the ability of EphB4-Fc to induce phosphorylation of ephrinB2 in human osteoclast precursors and subsequent down-regulation of the ephrinB2 target transcription factor, NFATc1,13 and inhibition of osteoclast differentiation (Figure 3). In contrast, although donor and MM patient MSCs express ephrinB2, we failed to detect phosphorylated ephrinB2 at baseline or after induction with EphB4-Fc (Figure 3A), suggesting that ephrinB2/EphB4 reverse signaling is nonfunctional in human MSCs.

EphB4-Fc induces reverse signaling in osteoclast precursors but not in MSCs. (A) Osteoclast precursors (pOC) and MSCs from donors and MM patients were left untreated or stimulated with clustered EphB4-Fc (4 μg/mL) for 20 minutes and then subjected to Western blot. Note that ephrinB2 was expressed in pOC and MSCs (∼ 50-kDa band size) and that EphB4-Fc induced phosphorylation of ephrinB2 in pOC but not in donor or MM patient MSCs. (B) Human pOCs were treated with Fc or EphB4-Fc for 2 days and then subjected to quantitative RT-PCR for NFATc1 (ephrinB2 target). Note down-regulation of NFATc1 by EphB4-Fc. (C-D) Human pOCs were treated with Fc or EphB4-Fc for 7 to 10 days and then stained for TRAP. Note reduced number of TRAP-expressing multinucleated osteoclasts (red arrows) in EphB4-Fc–treated cultures.

EphB4-Fc induces reverse signaling in osteoclast precursors but not in MSCs. (A) Osteoclast precursors (pOC) and MSCs from donors and MM patients were left untreated or stimulated with clustered EphB4-Fc (4 μg/mL) for 20 minutes and then subjected to Western blot. Note that ephrinB2 was expressed in pOC and MSCs (∼ 50-kDa band size) and that EphB4-Fc induced phosphorylation of ephrinB2 in pOC but not in donor or MM patient MSCs. (B) Human pOCs were treated with Fc or EphB4-Fc for 2 days and then subjected to quantitative RT-PCR for NFATc1 (ephrinB2 target). Note down-regulation of NFATc1 by EphB4-Fc. (C-D) Human pOCs were treated with Fc or EphB4-Fc for 7 to 10 days and then stained for TRAP. Note reduced number of TRAP-expressing multinucleated osteoclasts (red arrows) in EphB4-Fc–treated cultures.

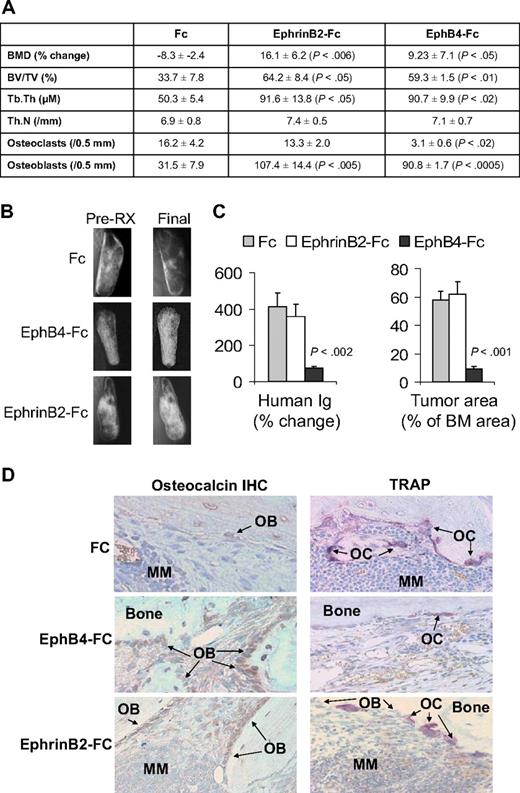

EphrinB2-Fc and EphB4-Fc affect bone parameters, osteoclastogenesis, osteoblastogenesis, and tumor growth in myelomatous bone

In vivo, we exploited our SCID-hu model19 to study the consequences of activation of forward signaling by ephrinB2-Fc or reverse signaling by EphB4-Fc on myeloma growth and disease manifestations. Hosts engrafted with myeloma cells from a patient with active disease were locally treated with Fc, ephrinB2-Fc, or EphB4-Fc for 4 weeks. Whereas BMD of the implanted bone was reduced by 8% plus or minus 3% from pretreatment levels in Fc-treated hosts, it was increased after ephrinB2-Fc and EphB4-Fc treatment by 16% plus or minus 6% (P < .006 vs Fc) and 9% plus or minus 7% (P < .05 vs Fc), respectively, compared with pretreatment levels (Figure 4A). Static histomorphometric analysis revealed increased bone parameters [bone volume/tissue volume (BV/TV) and trabecular thickness (Tb.Th)] in bones treated with ephrinB2-Fc or EphB4-Fc (Figure 4A). EphB4-Fc and ephrinB2-Fc increased the numbers of osteoblasts, whereas EphB4-Fc, but not ephrinB2-Fc, reduced osteoclast numbers in myelomatous bones (Figure 4A,D). Increased bone mass by the 2 chimeric proteins was also visualized by x-rays (Figure 4B).

EphrinB2-Fc and EphB4-Fc affect MM bone disease and tumor growth in SCID-hu mice. SCID-hu mice (n = 15) engrafted with primary myeloma cells from a single patient were treated with Fc, ephrinB2-Fc, or EphB4-Fc (5 mice/group) for 4 weeks using Alzet pumps that released 0.11 μg/hr of each compound directly into the implanted bones. (A) Changes in BMD of the implanted bone from pretreatment levels, histomorphometric parameters, and numbers of osteocalcin-expressing osteoblasts and TRAP-expressing osteoclasts in myelomatous bones. Note EphrinB2-Fc and EphB4-Fc increased bone formation and osteoblast numbers, but only EphB4-Fc reduced the number of osteoclasts. (B) Representative x-ray radiographs of myelomatous bones treated with indicated agents. Note that, in contrast to Fc, ephrinB2-Fc and EphB4-Fc treatment resulted in increased bone mass. (C) Changes in human Ig levels (left panel) and MM tumor area (right panel) in the implanted human bone after treatment with control Fc, ephrinB2-Fc, or EphB4-Fc for 4 weeks. Note inhibition of MM growth by EphB4-Fc but not ephrinB2-Fc. (D) Representative bone sections with immunohistochemical (IHC) staining for osteocalcin (left panels) or stained for TRAP (right panels). Note that ephrinB2-Fc and EphB4-Fc increased numbers of osteoblasts, but only EphB4-Fc reduced numbers of osteoclasts in myelomatous bones.

EphrinB2-Fc and EphB4-Fc affect MM bone disease and tumor growth in SCID-hu mice. SCID-hu mice (n = 15) engrafted with primary myeloma cells from a single patient were treated with Fc, ephrinB2-Fc, or EphB4-Fc (5 mice/group) for 4 weeks using Alzet pumps that released 0.11 μg/hr of each compound directly into the implanted bones. (A) Changes in BMD of the implanted bone from pretreatment levels, histomorphometric parameters, and numbers of osteocalcin-expressing osteoblasts and TRAP-expressing osteoclasts in myelomatous bones. Note EphrinB2-Fc and EphB4-Fc increased bone formation and osteoblast numbers, but only EphB4-Fc reduced the number of osteoclasts. (B) Representative x-ray radiographs of myelomatous bones treated with indicated agents. Note that, in contrast to Fc, ephrinB2-Fc and EphB4-Fc treatment resulted in increased bone mass. (C) Changes in human Ig levels (left panel) and MM tumor area (right panel) in the implanted human bone after treatment with control Fc, ephrinB2-Fc, or EphB4-Fc for 4 weeks. Note inhibition of MM growth by EphB4-Fc but not ephrinB2-Fc. (D) Representative bone sections with immunohistochemical (IHC) staining for osteocalcin (left panels) or stained for TRAP (right panels). Note that ephrinB2-Fc and EphB4-Fc increased numbers of osteoblasts, but only EphB4-Fc reduced numbers of osteoclasts in myelomatous bones.

At the end of the experimental period, levels of human Ig in mice sera were increased by 412% plus or minus 76% and 361% plus or minus 68% from pretreatment levels in Fc-treated and ephrinB2-Fc–treated groups, respectively, whereas they were reduced by 74% plus or minus 9% (P < .002 vs Fc) from pretreatment levels in the EphB4-Fc group (Figure 4C). Similar differences were observed by analyzing the myeloma infiltration area in the human marrow (Figure 4C). Whereas the effect of ephrinB2-Fc on bone formation is not surprising, the marked effect of EphB4-Fc on bone formation cannot simply be explained by reduction of osteoclastogenesis, although the increased bone mass in transgenic EphB4 mice was attributed to inhibition of osteoclastogenesis.13 EphB4-Fc could impact bone formation through interaction with other BM stromal cells.

EphrinB2-Fc and EphB4-Fc affect neovascularization in myelomatous bone

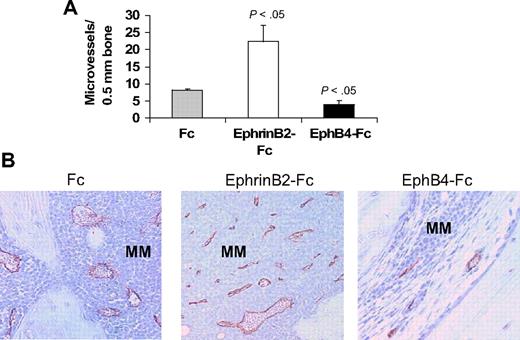

The ephrinB2/EphB4 axis is involved in regulation of vasculogenesis and angiogenesis.11,12 Therefore, we also examined numbers of human CD34-reactive neovessels in these myelomatous bones. Relative to Fc-treated bones, the number of neomicrovessels was reduced in EphB4-Fc–treated bones, even in areas with residual MM, and was increased after treatment with ephrinB2-Fc (Figure 5).

EphrinB2-Fc and EphB4-Fc affect neovascularization in myelomatous bone. Human bone sections from myelomatous SCID-hu mice treated with Fc, ephrinB2-Fc, or EphB4-Fc were immunohistochemically stained for human CD34. (A) Numbers of human CD34-reactive neomicrovessels in myelomatous bones were increased by ephrinB2-Fc and reduced by EphB4-Fc treatment. (B) Representative immunohistochemical staining for CD34, demonstrating the effect of ephrinB2-Fc and EphB4-Fc on MM-induced neovascularization.

EphrinB2-Fc and EphB4-Fc affect neovascularization in myelomatous bone. Human bone sections from myelomatous SCID-hu mice treated with Fc, ephrinB2-Fc, or EphB4-Fc were immunohistochemically stained for human CD34. (A) Numbers of human CD34-reactive neomicrovessels in myelomatous bones were increased by ephrinB2-Fc and reduced by EphB4-Fc treatment. (B) Representative immunohistochemical staining for CD34, demonstrating the effect of ephrinB2-Fc and EphB4-Fc on MM-induced neovascularization.

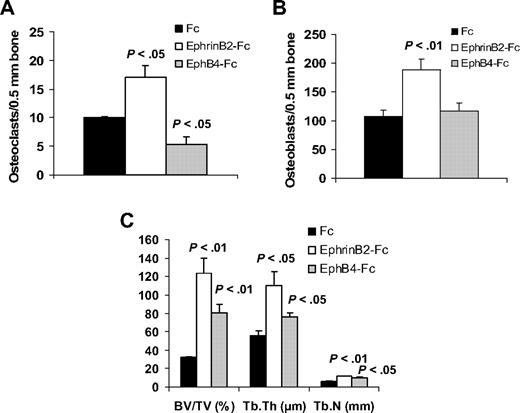

EphrinB2-Fc and EphB4-Fc affect bone parameters in nonmyelomatous bones

In nonmyelomatous SCID-hu mice, the numbers of osteoclasts were reduced in EphB4-Fc–treated bones and increased in ephrinB2-Fc–treated bones, compared with the Fc-treated group (Figure 6). Treatment with each of the chimeric proteins resulted in increased osteoblast numbers, although the effect of ephrinB2-Fc was more profound.

EphrinB2-Fc or EphB4-Fc affects bone parameters in nonmyelomatous bones. Hosts were treated with Fc, ephrinB2-Fc, or EphB4-Fc (5 mice/group) for 4 weeks using Alzet pumps that released 0.11 μg/hr of each compound directly into the implanted bones. (A-B) Numbers of osteoclasts (A) and osteoblasts (B) in implanted bones. EphrinB2-Fc increased numbers of osteoclasts and osteoblasts, whereas EphB4-Fc reduced osteoclast numbers but had no effect on osteoblast numbers. (C) Changes in histomorphometric parameters of implanted bones. Note increased levels of BV/TV, Tb.Th, and Tb.N by ephrinB2-Fc and EphB4-Fc.

EphrinB2-Fc or EphB4-Fc affects bone parameters in nonmyelomatous bones. Hosts were treated with Fc, ephrinB2-Fc, or EphB4-Fc (5 mice/group) for 4 weeks using Alzet pumps that released 0.11 μg/hr of each compound directly into the implanted bones. (A-B) Numbers of osteoclasts (A) and osteoblasts (B) in implanted bones. EphrinB2-Fc increased numbers of osteoclasts and osteoblasts, whereas EphB4-Fc reduced osteoclast numbers but had no effect on osteoblast numbers. (C) Changes in histomorphometric parameters of implanted bones. Note increased levels of BV/TV, Tb.Th, and Tb.N by ephrinB2-Fc and EphB4-Fc.

Overall, treatment of the implanted bones with ephrinB2-Fc and, to a lesser extent with EphB4-Fc, resulted in higher bone parameters, such as BV/TV, Tb.Th, and trabecular number (Tb.N; Figure 6).

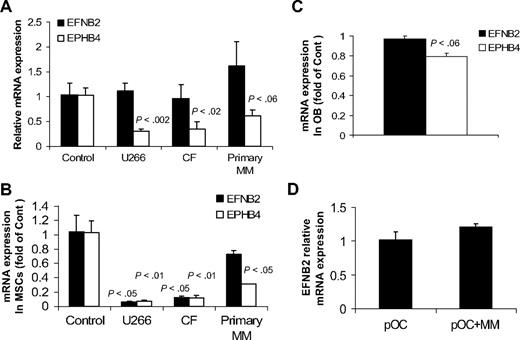

Effects of MM on expression of EFNB2 and EPHB4 in bone in vivo and in cultured MSCs, osteoblasts, and osteoclast precursors

Because our current and reported studies19,24,28,29 demonstrated the ability of primary MM to induce osteolytic bone disease and reduce expression of EphB4 and ephrinB2 in normal bones in SCID-hu mice, we sought to test whether myeloma cells directly affect expression of EFNB2 and EPHB4 in nonmyelomatous implanted bones in SCID-hu mice, in MSCs and osteoblasts generated from fetal bones, and in normal osteoclast precursors. In vivo, conditioned media from cultures of myeloma cell lines (U266 and CF23 ) and primary myeloma plasma cells or control media were injected twice a day for 3 days into the surrounding area of the implanted human bone in nonmyelomatous SCID-hu mice (5 mice/conditioned media from each source). In this experiment, conditioned media from the 2 myeloma cell lines or primary myeloma cells induced down-regulation of EPHB4 expression but had no effect on EFNB2 expression in the implanted human bones (Figure 7A). To further understand the consequences of MM growth on ephrinB2/EphB2 axis in our animal model, fetal human MSCs were cultured alone or cocultured with U266 and CF cells or primary myeloma plasma cells for 3 days using transwell inserts as described.22 Our analysis revealed a marked down-regulation of EPHB4 in MSCs cocultured with the 3 types of myeloma cells (Figure 7B). EFNB2 expression was markedly down-regulated in MSCs by the 2 cell lines, U266 and CF, but not by primary myeloma plasma cells (Figure 7B).

Effects of MM on expression of EFNB2 and EPHB4 in human bones in vivo and in cultured MSCs, osteoblasts, and osteoclast precursors. (A) Conditioned media from cultures of myeloma cell lines (U266 and CF) and primary myeloma plasma cells or control media were injected twice a day for 3 days into the surrounding area of the implanted human bone in nonmyelomatous SCID-hu mice (5 mice/conditioned media from each source). Note reduced expression of EPHB4 but not EFNB2 by myeloma cell-conditioned media. (B) Fetal human MSCs were cultured alone or cocultured with U266 and CF MM lines and primary myeloma cells for 3 days using transwell inserts22 and then subjected to quantitative RT-PCR analysis. Note reduced expression of EPHB4 in MSCs cocultured with all types of myeloma cells, whereas EFNB2 expression was reduced in coculture with U266 and CF cells but not primary myeloma cells. P values represent differences between cultured and cocultured MSCs. (C) Fetal osteoblasts (OB) similarly cocultured with primary myeloma plasma cells for 3 days had reduced EPHB4 expression as determined by quantitative RT-PCR analysis. (D) Osteoclast precursors (pOC) were cultured alone or cocultured with primary myeloma cells in osteoclastic media. After 3 days, myeloma cells were removed from cocultures and the pOC subjected to quantitative RT-PCR analysis. Myeloma cells had no effect on EFNB2 expression by pOC.

Effects of MM on expression of EFNB2 and EPHB4 in human bones in vivo and in cultured MSCs, osteoblasts, and osteoclast precursors. (A) Conditioned media from cultures of myeloma cell lines (U266 and CF) and primary myeloma plasma cells or control media were injected twice a day for 3 days into the surrounding area of the implanted human bone in nonmyelomatous SCID-hu mice (5 mice/conditioned media from each source). Note reduced expression of EPHB4 but not EFNB2 by myeloma cell-conditioned media. (B) Fetal human MSCs were cultured alone or cocultured with U266 and CF MM lines and primary myeloma cells for 3 days using transwell inserts22 and then subjected to quantitative RT-PCR analysis. Note reduced expression of EPHB4 in MSCs cocultured with all types of myeloma cells, whereas EFNB2 expression was reduced in coculture with U266 and CF cells but not primary myeloma cells. P values represent differences between cultured and cocultured MSCs. (C) Fetal osteoblasts (OB) similarly cocultured with primary myeloma plasma cells for 3 days had reduced EPHB4 expression as determined by quantitative RT-PCR analysis. (D) Osteoclast precursors (pOC) were cultured alone or cocultured with primary myeloma cells in osteoclastic media. After 3 days, myeloma cells were removed from cocultures and the pOC subjected to quantitative RT-PCR analysis. Myeloma cells had no effect on EFNB2 expression by pOC.

Similarly, expression of EPHB4, but not EFNB2, was moderately down-regulated in osteoblasts (generated from fetal MSCs) after coculture with primary myeloma plasma cells (Figure 7C). It is noteworthy that differentiating osteoblasts expressed lower levels of EPHB4 relative to MSCs (S.Y., unpublished data, May 2009). We also found that primary myeloma cells had no effect on EFNB2 expression in osteoclast precursors using a cell-contact coculture condition27 (Figure 7D). Taken together, these results suggest that, in addition to abnormal underexpression of EPHB4 and EFNB2 in patient MSCs, myeloma cells may also directly induce down-regulation of EPHB4 and, in certain cases, also EFNB2 expression in MSCs.

Myeloma cells express very low levels of EFNB2 and EPHB4 and do not respond to EphrinB2-Fc or EphB4-Fc in vitro

Primary myeloma cells and myeloma cell lines expressed very low to undetectable levels of EPHB4 and EFNB2 and did not respond to ephrinB2-Fc or EphB4-Fc in vitro (supplemental Figures 2-3), suggesting that the reduced MM burden in EphB4-Fc–treated SCID-hu mice was indirectly mediated via modulation of the BM environment, including inhibition of osteoclastogenesis and neovascularization and stimulation of osteoblast activity. In contrast, EphrinB2-Fc stimulated osteoblastogenesis, but also unwanted angiogenesis, and had no impact on osteoclast numbers, with a net effect of having no impact on MM growth.

Discussion

EphrinB2/EphB4 bidirectional signaling has been implicated in the coupling of bone resorption to bone formation.13,14 In the present study, we provide evidence that expression of ephrinB2 and EphB4 is reduced in cultured MSCs from MM patients and in osteoblasts or osteoclasts in myelomatous bones. Reduced expression of EPHB4 (but not EFNB2) in nonmyelomatous human bones was detected after treatment of SCID-hu mice with conditioned media from cultures of myeloma cell lines or primary cells. Expression of EPHB4 and EFNB2 was reduced in fetal MSCs cocultured with myeloma cell lines; whereas in a similar coculture system, primary myeloma plasma cells reduced EPHB4 but not EFNB2 expression in fetal MSCs. Recombinant Wnt3a, which has been shown to prevent MM bone disease,17 induced up-regulation of EPHB4 in MM patient MSCs. In the SCID-hu model, in which primary myeloma plasma cells manifest in a nonmyelomatous microenvironment, suppress osteoblastogenesis, and stimulate osteoclastogenesis and angiogenesis,19,24,28,30 activation of either forward or reverse signaling by chimeric proteins inhibited MM-induced osteolysis, increased osteoblastogenesis, and stimulated bone formation in the myelomatous bones. However, whereas induction of reverse signaling by EphB4-Fc was associated with inhibition of osteoclastogenesis and angiogenesis and reduction of tumor burden, induction of forward signaling by ephrinB2-Fc had no effect on osteoclastogenesis or tumor burden but increased angiogenesis in myelomatous bones. EphrinB2-Fc and EphB4-Fc similarly affected bone parameters in nonmyelomatous bones. These results suggest that ephrinB2/EphB4-mediated communication between osteoclasts and osteoblasts13 and between cells of osteoblastic lineage14 is impaired in myelomatous bones partially because of reduced expression of these molecules by osteogenic cells.

The typically osteolytic bone disease associated with MM results from the uncoupling of the processes of osteoclastic bone resorption and osteoblastic bone formation in areas adjacent to tumor cells.10 Previous studies indicate that MM patient MSCs have altered phenotypic and genomic profiles and impaired osteogenic potential.4,31,–33 Our study provides further evidence for abnormal properties of MM patient MSCs with regard to expression of ephrinB2 and EphB4. Our findings also indicate that myeloma cells secrete factors that reduce EPHB4 expression in bone. Mounting studies support the notion that myeloma cells produce inhibitors of canonical Wnt signaling (eg, DKK1) that suppress osteoblastogenesis and bone formation6,9,34,35 and stimulate osteoclastogenesis.36 Increasing Wnt signaling with Wnt3a17 or lithium chloride18 or by inhibiting DKK1 activity16 have been shown to be effective approaches for treatment of MM bone disease in preclinical models. Thus, although EPHB4 expression is reduced in patient MSCs and in myelomatous bones, and because myeloma cells do not seem to directly affect EFNB2 expression in osteoclast precursors, pharmacologic approaches to up-regulate EPHB4, including but not limited to Wnt signaling-inducing agents, may help restore coupling of bone remodeling in clinical MM by promoting forward and reverse signaling in osteoblasts and osteoclast precursors, respectively.

Interestingly, in SCID-hu mice, ephrinB2-Fc stimulated osteoclastogenesis in nonmyelomatous but not myelomatous bones, whereas EphB4-Fc stimulated osteoblastogenesis in myelomatous but not nonmyelomatous bones. These results suggest that, in nonmyelomatous bones, ephrinB2-Fc-induced osteoblastogenesis is expectedly accompanied by stimulation of osteoclastogenesis; whereas in myelomatous bone, where osteoclast activity is markedly high, ephrinB2-Fc has no further impact on osteoclastogenesis. The mechanism by which EphB4-Fc stimulates osteoblastogenesis in myelomatous bones is yet unclear and will require further investigation.

Moreover, reduced expression of ephrinB2 in primary myelomatous bones (Figure 1F), but not in MSCs after coculture with primary myeloma cells (Figure 7), emphasizes the differences between in vivo and in vitro experimental conditions and suggests that in vivo additional microenvironmental factors (eg, oxidative stress) may affect expression of these genes in myelomatous bones.

Our in vitro and in vivo data support the notion that activation of either forward or reverse signaling affects bone remodeling, resulting in increased bone formation. However, the involvement of ephrinB2/EphB4 bidirectional signaling in bone homeostasis is not entirely understood. For instance, although Allan et al14 proposed that expression of ephrinB2 and EphB4 within a population of osteogenic cells is involved in osteoblast differentiation through autocrine or paracrine fashions, an actual reverse signaling in osteogenic cells has not been demonstrated. Our study reveals, for the first time, that, in contrast to effective induction of reverse signaling in osteoclast precursors, such signaling could not be induced in ephrinB2-expressing MSCs from donors and MM patients. These results suggest that ephrinB2 expressed on the surface of osteogenic cells and osteoclast precursors induces forward signaling in osteogenic cells and stimulates their differentiation. Conversely, EphB4 expressed on the surface of osteogenic cells induces reverse signaling in osteoclast precursors and inhibits their differentiation but is incapable of inducing reverse signaling through ephrinB2 in osteogenic cells. The nature of ephrinB2 signaling in osteogenic cells will require further investigation.

Our results indicate that the number of neomicrovessels was reduced in EphB4-Fc–treated bones and increased after treatment with ephrinB2-Fc. Although mounting evidence indicates that the ephrinB2/EphB4 axis directly regulates vasculogenesis and angiogenesis, the consequences of forward or reverse signaling on such processes are somewhat controversial and depend on experimental and physiologic settings, reflecting the complexity of this signaling pathway.11,37,38 Arterial endothelial cells specifically express EphB4, whereas venous endothelial cells express ephrinB2.37 These factors are also expressed in neo-angiogenic vessels.38

Previous reports have demonstrated the involvement of ephrinB2 in vasculogenesis and angiogenesis. Stroma cells expressing ephrinB2 were shown to be involved in vascular network formation, and it has been demonstrated that ephrinB2/EphB4 signaling between endothelial cells and surrounding mesenchymal cells plays an essential role in vasculogenesis, angiogenesis, and vessel maturation.39,40 EphB4 activation by ephrinB2 triggers sprout formation by endothelial cells.41 In vivo, ephrinB2-Fc administration enhanced endothelial cell proliferation and capillary density in animal models for myocardial infarction.42 Forward signaling also promoted SDF-1–induced endothelial cell chemotaxis and branching remodeling.43 Interestingly, overexpression of ephrinB2 in colon cancer cells or treating murine lung carcinoma cells with ephrinB2-Fc xenograft models44,45 was associated with increased microvessel density, but these vessels were considered dysfunctional or nonproductive, resulting in tumor growth impairment. The latest studies may partially explain the lack of increased MM burden in ephrinB2-Fc–treated myelomatous bones. It was also reported that EphB4 expressed on the surface of breast cancer cells promoted angiogenesis and tumor growth in a xenograft model by activating ephrinB2 reverse signaling in the vasculature.46

Clearly, additional studies are required to elucidate the role of the ephrinB2/ EphB4 system in neovascularization of solid and so-called liquid (eg, blood cancers) tumors. Our findings suggest a distinctive role for the in axis in myelomatous BM neovascularization, where vasculogenesis and angiogenesis are concurrently modulated by MM.47

In conclusion, our study suggests that MSCs from MM patients underexpress EphrinB2 and EphB4 and that myeloma cells negatively regulate their expression in MSCs. Dysregulation of these factors may contribute to uncoupling of bone remodeling in MM lytic lesions. Therefore, approaches to up-regulate expression of endogenous EphB4 and ephrinB2 in osteoprogenitors (eg, treatment with Wnt3a) or exogenously increase EphB4 levels (eg, treatment with EphB4-Fc) may help restore coupling of bone remodeling and simultaneously inhibit MM tumor growth, bone disease, and angiogenesis.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the faculty, staff, and patients of the Myeloma Institute for Research and Therapy for their support and the Office of Grants and Scientific Publications at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences for editorial assistance during the preparation of this manuscript.

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (grant CA-093897; S.Y.) and the Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation (Senior and Translational Research Award; S.Y.).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: A.P. performed research, interpreted the data, and wrote the paper; W.L. and X.L. performed research; S.K. performed in vitro studies; J.D.S. performed global gene expression profiling; B.B. provided patients' materials and interpreted the data; and S.Y. performed research, conceptualized the work, analyzed and interpreted the data, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Shmuel Yaccoby, Myeloma Institute for Research and Therapy, Winthrop P. Rockefeller Cancer Institute, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, 4301 W Markham, Slot 776, Little Rock, AR 72205; e-mail: yaccobyshmuel@uams.edu.