Direct sequencing of VWF genomic DNA in 21 patients with type 3 von Willebrand disease (VWD) failed to reveal a causative homozygous or compound heterozygous VWF genotype in 5 cases. Subsequent analysis of VWF mRNA led to the discovery of a deletion (c.221-977_532 + 7059del [p.Asp75_Gly178del]) of VWF in 7 of 12 white type 3 VWD patients from 6 unrelated families. This deletion of VWF exons 4 and 5 was absent in 9 patients of Asian origin. We developed a genomic DNA-based assay for the deletion, which also revealed its presence in 2 of 34 type 1 VWD families, segregating with VWD in an autosomal dominant fashion. The deletion was associated with a specific VWF haplotype, indicating a possible founder origin. Expression studies indicated markedly decreased secretion and defective multimerization of the mutant VWF protein. Further studies have found the mutation in additional type 1 VWD patients and in a family expressing both type 3 and type 1 VWD. The c.221-977_532 + 7059del mutation represents a previously unreported cause of both types 1 and 3 VWD. Screening for this mutation in other type 1 and type 3 VWD patient populations is required to elucidate further its overall contribution to VWD arising from quantitative deficiencies of VWF.

Introduction

von Willebrand disease (VWD) is a hereditary bleeding disorder resulting from quantitative (type 1 and type 3 VWD) or qualitative (type 2 VWD) abnormalities of the multimeric plasma glycoprotein von Willebrand factor (VWF).1,–3 VWF has essential roles in primary hemostasis where it functions in an adhesive matrix between platelets and subendothelial components at sites of vascular injury in vessels subject to high shear stress.4,5 VWF also acts as a carrier for procoagulant factor VIII (FVIII) in the circulation

Type 3 VWD, the result of markedly decreased or absent VWF, is associated with moderate to severe bleeding symptoms, including epistaxis, menorrhagia, arthropathy, and postoperative bleeding.6 It is an autosomal recessive inherited bleeding disorder with a prevalence of approximately 0.5 to 1 person per million in the general population,7 although prevalence may be as high as 6 per million in populations where consanguinity is common.8 Originally, it was assumed that type 3 VWD was caused by large deletions of the gene encoding VWF (VWF). Of 107 mutations reported to cause type 3 VWD (International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis [ISTH] SSC VWF database9 ), there are only 11 (10%) reports of large or partial gene deletions. These deletions range in size from a single exon10 through several exons11,,–14 to the entire gene.15,,–18 Heterozygous carriers of deletions have so far all been reported to be asymptomatic and do not have significant bleeding symptoms. Approximately 83% of VWF mutations in type 3 VWD are made up of mutations associated with a VWF-null allele (ie, nonsense mutations, deletions, splice site mutations, and small insertions). Missense mutations account for 17% of sequence variants responsible for type 3 VWD.

Type 1 VWD, reportedly the most common form of the disorder,19 is caused by a partial quantitative deficiency of VWF and is considered classically to show an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern.1,2 The main symptom of type 1 VWD is a significant mucocutaneous bleeding history; however, a definitive diagnosis is often complicated by variable expressivity and incomplete penetrance.20 There are several environmental factors, such as age and stress as well as other genetic modifiers at different loci, particularly ABO blood group, which may influence the observed phenotype.2,21,,,,,,–28 Recent studies have investigated the molecular pathogenesis of type 1 VWD and have found inconclusive results regarding the underlying genetic defects associated with the disease in a large proportion of patients.29,–31 These findings support the hypothesis that the type 1 VWD phenotype is not always associated with pathogenic mechanisms involving VWF and indicate limited utility for conventional genetic diagnosis in type 1 VWD.32

The ISTH VWF mutation database9 reports 144 candidate VWF mutations associated with type 1 VWD. These include 93 missense mutations, 9 small deletions, 13 splice site mutations, 19 promoter region mutations, 2 insertions, one duplication, and 7 nonsense mutations. It may be unclear how a mutation on a single VWF allele gives rise to a clinical bleeding disorder when the second allele may be predicted to maintain VWF at levels sufficient for normal hemostasis, although a dominant-negative mechanism has been demonstrated in some cases.33,34 In this respect, heterozygous carriers of type 3 VWD are generally clinically asymptomatic.

The primary aim of our study was to identify the underlying molecular pathogenesis of type 3 VWD in 21 patients (20 index cases and 1 family member) with this disorder who attend the adult and pediatric hemophilia centers at Central Manchester National Health Service Trust. We initially used genomic DNA sequence analysis of the essential regions of VWF (52 exons and flanking intronic regions, 5′ promoter region, and the 3′ untranslated region)29 to identify homozygosity or compound heterozygosity in 16 type 3 VWD patients for a variety of VWF mutations (M.S.S., A.M.C., P.H.B.B.-M., C.R.M.H., A.M.W., S.K., manuscript submitted). Homozygosity for a previously unreported in-frame deletion mutation removing exons 4 and 5 of VWF was found in 2 index cases and one family member. Subsequent RNA analysis revealed this deletion to be present in the heterozygous state in a further 4 unrelated type 3 VWD index cases. This information was used to design an assay for the deletion that could be applied at the genomic DNA level and was used to investigate the presence of the deletion in 34 index cases previously recruited into a United Kingdom national study of type 1 VWD.29

Methods

Ethical approval

The study of type 3 VWD patients in Manchester was approved by the Central Manchester Local Research Ethics Committee (Manchester, United Kingdom). The study of VWF genotype in United Kingdom patients with type 1 VWD was approved by the Multi-Center Research Ethics Committee for Wales.

Patients

Twenty index cases and one family member with an existing diagnosis of type 3 VWD (VWF:antigen [VWF:Ag] < 5 IU/dL, VWF:ristocetin cofactor activity [VWF:RCo] undetectable) were recruited (Table 1 phenotypic data). Thirty-four patients with type 1 VWD previously recruited into a United Kingdom national study29 were also investigated. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. A total of 20 mL of blood was collected from each patient in four 5 mL tubes containing 0.105 M sodium citrate. Samples were processed as soon as possible after collection to ensure the integrity of the platelets for RNA extraction.

Phenotypic data for all patients

| Family:patient . | VWD type . | Age, y . | ABO blood group . | VWF:Ag, IU/dL . | VWF:RCo, IU/dL . | FVIII, IU/dL . | Multimer pattern . | Bleeding symptoms* . | Mutation present . | Zygosity† . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1:1 | 3 | 55 | AB | Not detected | Not detected | Not detected | None detected | E, D, S, O, B, M, J, G | Ex4-5del + Indel | Cpd het |

| 1:2 | 1 | 18 | O | 22 | 13 | 34 | Normal | B, D | Ex4-5del | Het |

| 2:1 | 3 | 48 | A | 4 | Not detected | 19 | None detected | M, E | Ex4-5del | Het |

| 3:1 | 3 | 55 | B | < 1 | Not detected | < 1 | Not done | E, S, J, G | Ex4-5del + frameshift | Cpd het |

| 4:1 | 3 | 46 | A | 3 | Not detected | 13 | Trace | E, O, J | Ex4-5del + missense | Cpd het |

| 5:1 | 3 | 19 | AB | Not detected | Not detected | 1 | None detected | E, O, J, G | Ex4-5del | Hom |

| 6:1 | 3 | 46 | A | Not detected | Not detected | 2 | None detected | E, D, J, I, G | Ex4-5del | Hom |

| 6:2 | 3 | 42 | O | Not detected | Not detected | 2 | None detected | D, J, G, O | Ex4-5del | Hom |

| 7:1 | 1‡ | 81 | B | 81 | 105 | 99 | Normal | None | Ex4-5del | Het |

| 7:2 | 1 | 45 | O | 16 | 11 | 37 | Normal | O, D, S, B, M | Ex4-5del | Het |

| 7:3 | 1 | 18 | A | 41 | 43 | 89 | Normal | None, all surgery with DDAVP cover | Ex4-5del | Het |

| 7:4 | 1 | 15 | O | 25 | 21 | 107 | Normal | None, all surgery with DDAVP cover | Ex4-5del | Het |

| 8:1 | 1 | 32 | O | 20 | 28 | 89 | Normal | E, M, B, Sur | Ex4-5del | Het |

| 8:2 | 1 | 8 | A | < 20 | < 20 | 47 | Reduced HMW | B, E, surgery with DDAVP cover | Ex4-5del | Het |

| 9:1 | 3 | 1 | A | Not detected | Not detected | 2 | Dimers only detected | I, Sur | Ex4-5del + Splice site | Cpd het |

| 9:2 | Possible 1 | 32 | 39 | 37 | 145 | Normal | No clinical history available | Ex4-5del | Het | |

| 10:1 | 1 | 18 | O | 15 | 11 | 90 | Normal | E, B | Ex4-5del | Het |

| Family:patient . | VWD type . | Age, y . | ABO blood group . | VWF:Ag, IU/dL . | VWF:RCo, IU/dL . | FVIII, IU/dL . | Multimer pattern . | Bleeding symptoms* . | Mutation present . | Zygosity† . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1:1 | 3 | 55 | AB | Not detected | Not detected | Not detected | None detected | E, D, S, O, B, M, J, G | Ex4-5del + Indel | Cpd het |

| 1:2 | 1 | 18 | O | 22 | 13 | 34 | Normal | B, D | Ex4-5del | Het |

| 2:1 | 3 | 48 | A | 4 | Not detected | 19 | None detected | M, E | Ex4-5del | Het |

| 3:1 | 3 | 55 | B | < 1 | Not detected | < 1 | Not done | E, S, J, G | Ex4-5del + frameshift | Cpd het |

| 4:1 | 3 | 46 | A | 3 | Not detected | 13 | Trace | E, O, J | Ex4-5del + missense | Cpd het |

| 5:1 | 3 | 19 | AB | Not detected | Not detected | 1 | None detected | E, O, J, G | Ex4-5del | Hom |

| 6:1 | 3 | 46 | A | Not detected | Not detected | 2 | None detected | E, D, J, I, G | Ex4-5del | Hom |

| 6:2 | 3 | 42 | O | Not detected | Not detected | 2 | None detected | D, J, G, O | Ex4-5del | Hom |

| 7:1 | 1‡ | 81 | B | 81 | 105 | 99 | Normal | None | Ex4-5del | Het |

| 7:2 | 1 | 45 | O | 16 | 11 | 37 | Normal | O, D, S, B, M | Ex4-5del | Het |

| 7:3 | 1 | 18 | A | 41 | 43 | 89 | Normal | None, all surgery with DDAVP cover | Ex4-5del | Het |

| 7:4 | 1 | 15 | O | 25 | 21 | 107 | Normal | None, all surgery with DDAVP cover | Ex4-5del | Het |

| 8:1 | 1 | 32 | O | 20 | 28 | 89 | Normal | E, M, B, Sur | Ex4-5del | Het |

| 8:2 | 1 | 8 | A | < 20 | < 20 | 47 | Reduced HMW | B, E, surgery with DDAVP cover | Ex4-5del | Het |

| 9:1 | 3 | 1 | A | Not detected | Not detected | 2 | Dimers only detected | I, Sur | Ex4-5del + Splice site | Cpd het |

| 9:2 | Possible 1 | 32 | 39 | 37 | 145 | Normal | No clinical history available | Ex4-5del | Het | |

| 10:1 | 1 | 18 | O | 15 | 11 | 90 | Normal | E, B | Ex4-5del | Het |

The phenotypic data, bleeding history, and genotypic data are shown for the type 3 and type 1 VWD patient cohorts. All patients for whom data are reported here are white and of British origin. Laboratory reference ranges: VWF:Ag, 50 to 200 IU/dL; VWF:RCo, 50 to 200 IU/dL; and FVIII, 50 to 150 IU/dL.

Bleeding symptoms: E, epistaxis; O, oral bleeding; S, bleeding from cuts; D, dental bleeding; Sur, surgical bleed; B, bruising; M, menorrhagia; P, postpartum bleeding; J, joint bleeding; I, intracerebral bleed; and G, gastrointestinal bleed.

Zygosity: Hom, homozygous; Cpd het, compound heterozygous; and Het, heterozygous.

Individual is unaffected.

Nucleic acid extraction

Genomic DNA was extracted from leukocytes using an in-house ammonium acetate method. RNA was isolated from platelets using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen).

PCR primer design

Fifty-one primer sets were used to amplify the essential regions of VWF (52 exons and flanking intronic regions, 5′ promoter region, and the 3′ untranslated region). Primers had previously been designed in-house (sequences available on request) to amplify the sequence of interest at an annealing temperature of either 57°C or 59°C. Thirteen primer sets were designed using Primer 3 software35 to amplify the VWF cDNA. A further 18 primer sets, designated A to R, were designed to amplify the 26-kb region of genomic DNA from exon 3 to exon 6 of VWF.

Mutation analysis

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed to amplify the essential regions of VWF. The PCR mix contained 2.5 μL 10× PCR buffer, 0.75 μL 50 mM MgCl2, 0.5 units Taq polymerase, 2 μL 10 mM deoxynucleotide triphosphates (all supplied by Invitrogen), 6 μL appropriate forward and reverse primer (2 μM each), 12.65 μL sterile H2O, and 1 μL (approximately 250 ng) genomic DNA in a final volume of 25 μL. PCR was performed on a DNA thermal cycler (MWG Biotech) as follows: 95°C for 2 minutes, followed by 32 cycles of 94°C for 30 seconds, 59°C or 57°C for 45 seconds, 72°C for 1 minute 30 seconds, and a final extension at 72°C for 5 minutes. PCR products were visualized on a 1.5% (wt/vol) agarose gel. PCR product purification was performed using microCLEAN (Web Scientific) before cycle sequencing using Big-Dye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems). Sequencing reaction products were purified using an in-house ethanol precipitation method and resuspended in formamide (Applied Biosystems) before direct sequencing on an Applied Biosystems AB3130xl DNA Sequencer. Mutation detection was performed using the Staden software package.36 Each candidate mutation was confirmed by repeat PCR and sequencing.

cDNA analysis

cDNA synthesis of platelet-derived RNA was achieved using random hexameric primers according to the manufacturer's instructions (M-MLV Reverse Transcription System; Invitrogen). VWF cDNA was then analyzed by standard PCR methods (see “Mutation analysis”).

Mapping of the VWF exons 4 and 5 deletion breakpoint

The exact locations of the deletion breakpoints in 3 type 3 VWD patients in whom the mutation was initially identified at the genomic level were determined by primer walking. The genomic region from exon 3 to exon 6 (26 kb) was amplified in approximately 1.5 kb overlapping fragments using 18 primer sets designated A to R. Direct sequencing of a truncated product obtained using combinations of these primers was performed, and further primers were then designed to amplify a smaller product (1084 bp) so that sequencing could be used to determine the precise deletion breakpoint. The Delmap primer sequences used in the assay specific for the detection of the deletion were as follows: forward primer: 5′-gtagcgcgacggccagtCCTATCTTTCCTATTTCCATTAATTTCT-3′; reverse primer: 5′-cagggcgcag-cgatgacATGCTAATGGATCAGAATTCATATTGT-3′.

These primers were tailed with universal “N13” tails (lower case letters in primer sequences), which are modifications of the universal M13 sequencing primer sequences, for use in subsequent cycle sequencing reactions.

The base and amino acid numbering of the novel VWF exons 4 and 5 deletion mutation was determined by reference to the published VWF sequence9 and the published VWF cDNA sequence. The mutation was described both at the cDNA level (c.) (RefSeq NCBI accession number NM_000552.3) and at the amino acid level (p.) (RefSeq NCBI accession number NP_000543.2) according to guidance issued by the Human Genome Variation Society.37

Confirmation of zygosity

A multiplex PCR was developed to confirm the homozygous/heterozygous status of the deletion. The reaction was performed based on the conditions described for genomic DNA using 35 cycles of denaturation, annealing, and extension. Two primer sets were used: (1) Delmap primers to amplify across the breakpoint (1084-bp product; 10 μL appropriate forward and reverse primer mix, 2 μM each); and (2) primers to amplify across exons 4 and 5 (1694-bp product) as an internal control (6 μL appropriate forward and reverse primer mix, 2 μM each). The volume of H2O added to the reaction was altered accordingly to achieve a total reaction volume of 25 μL. “N13” tailed primer sequences for the internal control were as follows: forward primer: 5′-gtagcgcgacggccagtCAACAGAGCACAACCCTGTC-3′; reverse primer: 5′-cagggcgcagcgatgacCTGCTCACTGCAAGTTCTCC-3′.

Mutation mechanism

The mutation mechanism was investigated by screening the DNA sequence flanking the deletion for common repetitive elements, interspersed repeats, and low complexity sequences.38 These are found throughout the genome and are implicated in the illegitimate recombination of DNA sequences. MarWiz39 was used to identify Matrix Association Regions within DNA sequences.40

Haplotype analysis

To investigate the possibility of a founder effect for the exons 4 and 5 deletion mutation, a haplotype panel of 25 VWF polymorphisms was constructed by reference to the ISTH SSC VWF database9 and the HapMap project.41 Polymorphisms were chosen to represent the length of the gene (Table 2). These were analyzed by DNA sequence analysis.

The haplotype panel studied in the patients with the ex4-5del mutation

| Haplotype panel . | Polymorphic frequency . | SNP reference number . | Common haplotype 1 . | Haplotype 2 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| c.-11254A>G | 0.37/0.63 | rs10774398 | G | G |

| c.-6231G>A | 0.35/0.65 | rs10774394 | A | A |

| c.-6117G>A | 0.33/0.67 | rs10849387 | A | A |

| c.-2709C>T | 0.71/0.29 | rs7964777 | T | T |

| c.-2661A>G | 0.71/0.29 | rs7954855 | G | G |

| c.-2527G>A | 0.71/0.29 | rs7965413 | A | A |

| c.-2522C>T | 0.96/0.04 | — | C | C |

| c.-64C>T | 0.35/0.65 | rs2286608 | T | T |

| c.-20C>T | 0.99/0.01 | rs41276742 | C | C |

| c.220+2421C>T | 0.35/0.65 | rs10849385 | T | T |

| c.220+3364G>A | 0.35/0.65 | rs7961844 | A | A |

| c.220+3793A>T | 0.34/0.66 | rs12307072 | T | T |

| c.221-1953G>T | 0.34/0.66 | rs3782716 | T | T |

| c.954T>A | 0.96/0.04 | rs1800387 | T* | T* |

| c.1411G>A | 0.45/0.55 | rs1800377 | G* | G* |

| c.1451G>A | 0.62/0.38 | rs1800378 | G* | G* |

| c.2282-42C>A | 0.46/0.54 | rs216293 | A* | C* |

| c.2365A>G | 0.67/0.33 | rs1063856 | A* | G* |

| c.2385T>C | Unknown | rs1063857 | T* | C* |

| c.3414C>T | 0.98/0.02 | rs4008538 | T* | C* |

| c.4141A>G | 0.46/0.54 | rs216311 | A* | G* |

| c.4641C>T | 0.42/0.58 | rs216310 | T* | C* |

| c.4665A>C | 0.64/0.36 | rs1800384 | A* | A* |

| c.5844C>T | 0.71/0.29 | rs216902 | C* | T* |

| c.7682T>A | 0.94/0.06 | rs35335161 | T* | T* |

| Haplotype panel . | Polymorphic frequency . | SNP reference number . | Common haplotype 1 . | Haplotype 2 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| c.-11254A>G | 0.37/0.63 | rs10774398 | G | G |

| c.-6231G>A | 0.35/0.65 | rs10774394 | A | A |

| c.-6117G>A | 0.33/0.67 | rs10849387 | A | A |

| c.-2709C>T | 0.71/0.29 | rs7964777 | T | T |

| c.-2661A>G | 0.71/0.29 | rs7954855 | G | G |

| c.-2527G>A | 0.71/0.29 | rs7965413 | A | A |

| c.-2522C>T | 0.96/0.04 | — | C | C |

| c.-64C>T | 0.35/0.65 | rs2286608 | T | T |

| c.-20C>T | 0.99/0.01 | rs41276742 | C | C |

| c.220+2421C>T | 0.35/0.65 | rs10849385 | T | T |

| c.220+3364G>A | 0.35/0.65 | rs7961844 | A | A |

| c.220+3793A>T | 0.34/0.66 | rs12307072 | T | T |

| c.221-1953G>T | 0.34/0.66 | rs3782716 | T | T |

| c.954T>A | 0.96/0.04 | rs1800387 | T* | T* |

| c.1411G>A | 0.45/0.55 | rs1800377 | G* | G* |

| c.1451G>A | 0.62/0.38 | rs1800378 | G* | G* |

| c.2282-42C>A | 0.46/0.54 | rs216293 | A* | C* |

| c.2365A>G | 0.67/0.33 | rs1063856 | A* | G* |

| c.2385T>C | Unknown | rs1063857 | T* | C* |

| c.3414C>T | 0.98/0.02 | rs4008538 | T* | C* |

| c.4141A>G | 0.46/0.54 | rs216311 | A* | G* |

| c.4641C>T | 0.42/0.58 | rs216310 | T* | C* |

| c.4665A>C | 0.64/0.36 | rs1800384 | A* | A* |

| c.5844C>T | 0.71/0.29 | rs216902 | C* | T* |

| c.7682T>A | 0.94/0.06 | rs35335161 | T* | T* |

Common haplotype 1 was observed in all patients heterozygous or homozygous for the deletion. Haplotype 2 was seen in 2 related type 3 VWD cases in the compound heterozygous state with haplotype 1. Common haplotype 1 and haplotype 2 are identical 5′ of the deletion and differ 3′ of the deletion.

— indicates not applicable.

3′ haplotype panel.

Expression and characterization of recombinant VWF

To create the construct lacking exons 4 and 5, site-directed mutagenesis was used using the QuikChange II XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) performed on the VWF expression vector pClneoVWFES (kindly provided by Dr P. Kroner, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI) according to the manufacturer's instructions (primers available on request). The fragment was excised with AfeI and NheI (located in VWF cDNA at 1067 bp and 14 042 bp, respectively) and ligated back into the expression vector pClneoVWFES to produce the cDNA expression vector pClneoVWFdel4-5. Plasmids were digested with HaeII to identify those with the deletion, and the mutant product was sequenced to confirm the presence of the deletion. Plasmid DNA was purified for transfection.

To evaluate the expression of the exon 4 and 5 deletion, HEK-293T cells were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium containing 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cells in the log phase of growth were seeded at a density such that cells were approximately 50% confluent the following day. Cells were transfected with 20 μg of DNA (3.2 μg β-galactosidase reporter construct, 6.8 μg calf thymus DNA, and 10 μg of the mutant or wild-type plasmids or 5 μg of each of these plasmids) using the calcium phosphate method. VWF was secreted into serum-free OptiMEM containing 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 1× insulin/selenium/transferrin G (Invitrogen). Forty-eight hours after transfection, media was collected and cells were lysed. Transfection efficiency was determined by measuring β-galactosidase reporter transcript using Berthold Lumat LB 9501 luminometer (Fisher Scientific) and the Galacto Light Plus reporter gene assay (Tropix). Quantification of the VWF:Ag present in the media and cell lysates was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using polyclonal rabbit antihuman antibody (Dako North America) against a standard normal human reference plasma (CRYOcheck, lot no. 7128; PrecisionBioLogic). Recombinant VWF (rVWF) from the media was concentrated and multimers analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-agarose gel electrophoresis. VWF:RCo was measured in duplicate by platelet aggregometry.

Results

Patient information and geographic origin

Of 21 patients (20 index cases and one family member) with type 3 VWD who were recruited into the study, 12 were of white origin and 9 were of Asian origin. Of the 12 white patients, 7 were found to carry a previously unreported deletion mutation spanning VWF exons 4 and 5. This deletion was not present in any of the Asian patients. All of the 7 white patients with the deletion, consisting of 6 index cases and 1 family member, were of British origin, so far as could be ascertained (Table 1).

Two of 34 index cases from type 1 VWD families also had the VWF exon 4 and 5 deletion. Both of these were of white British origin (Table 1).

Characterization of the deletion of exons 4 and 5

On initial genomic DNA amplification of VWF in type 3 VWD patients 5:1, 6:1, and 6:2 (Table 1), exons 4 and 5 failed to amplify, suggesting that these exons had undergone a homozygous deletion. Through the method of “primer walking,” using primer sets A to R, the deletion mutation was confirmed and the approximate breakpoints identified by failure to generate amplified products from G to M. Because primer sets A to R overlapped, the G forward and M reverse primers were used to amplify across the deleted region. This produced a PCR product of 1788 bp, rather than the expected product size of 10.4 kb. Further primers (Delmap) were designed and DNA sequencing used to map the deletion breakpoint. A wild-type PCR product using the Delmap primers would be expected to be 9715 bp in size. In the type 3 VWD patients homozygous for the exons 4 and 5 deletion, a product of 1084 bp was observed. Sequencing of this product identified a total in-frame deletion of 8631 bp from within intron 3 to a point within intron 5; c.221-977_532 + 7059del (p.Asp75_Gly178del), hereafter referred to as ex4-5del.

Identification of heterozygosity for ex4-5del

PCR analysis of platelet-derived VWF cDNA was performed on type 3 VWD patients 1:1, 2:1, 3:1, and 4:1 (Table 1) for whom the phenotype was unexplained by sequencing of genomic DNA (either no mutation or heterozygosity for only one mutation in VWF). This revealed a truncated PCR product in the region comprising VWF exon 2 to exon 7; an expected wild-type PCR product of 995 bp was replaced by one of 683 bp. At the VWF cDNA level, 2 patients (2:1 and 4:1) were compound heterozygous for the wild-type and the 683-bp products and 2 patients (1:1 and 3:1) were apparently homozygous for the mutant 683-bp product. The control was homozygous for the wild-type 995-bp product. Patients 1:1 and 3:1 had previously been found to be heterozygous for VWF nonsense mutations; associated RNA transcripts would therefore probably undergo nonsense-mediated decay, thereby explaining the apparent homozygosity for the deletion at the cDNA level in these 2 persons. Direct sequencing of the 683-bp truncated PCR product from all 4 patients revealed a deletion of the entire coding sequence for exon 4 and exon 5. The 995-bp product in patients 2:1 and 4:1 was sequenced and shown to be the expected wild-type sequence.

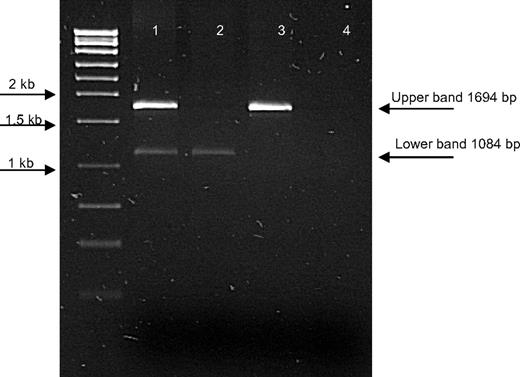

Given that the VWF exon 4 and exon 5 sequences were present at the genomic DNA level in type 3 VWD patients 1:1, 2:1, 3:1, and 4:1, it was considered probable that their absence at the RNA level was the result of the presence of a heterozygous deletion, masked during PCR amplification of genomic DNA by the presence of the normal sequence on the other VWF allele. To confirm this hypothesis, the Delmap primers were used at the genomic DNA level in these patients. This revealed the presence of an identical 1084-bp truncated PCR product, confirmed by DNA sequencing, as observed in the 3 patients homozygous for the deletion (5:1, 6:1, and 6:2). Examination of the DNA sequence surrounding the breakpoints in these PCR products showed complete homology between the homozygotes and heterozygotes for the deletion. The heterozygous nature of this deletion was confirmed in patients 1:1, 2:1, 3:1, and 4:1 by designing an assay containing 2 primer sets. One set of primers amplified across the breakpoint (1084-bp product); the second set amplified across exons 4 and 5 (1694-bp product) as a control (Figure 1). Both the 1084-bp and 1694-bp products were amplified in all 4 patients.

Gel image to illustrate the deletion of exons 4 and 5 at the DNA level. The top band (1694 bp) represents the wild-type PCR product, which amplifies across exons 4 and 5; bottom band (1084 bp), the PCR product designed to amplify across the deletion breakpoint. Lane 1 indicates a patient heterozygous for the deletion; lane 2, a patient homozygous for the deletion; lane 3, a wild-type control; and lane 4, a negative control.

Gel image to illustrate the deletion of exons 4 and 5 at the DNA level. The top band (1694 bp) represents the wild-type PCR product, which amplifies across exons 4 and 5; bottom band (1084 bp), the PCR product designed to amplify across the deletion breakpoint. Lane 1 indicates a patient heterozygous for the deletion; lane 2, a patient homozygous for the deletion; lane 3, a wild-type control; and lane 4, a negative control.

Identification of the deletion in type 1 VWD patients

Because of the high overall frequency of the ex4-5del mutation in the type 3 VWD cohort and the fact that heterozygosity for this mutation may not be identified by conventional analysis at the genomic DNA level, the possibility that this deletion may occur in patients with type 1 VWD was investigated. Thirty-four index cases from type 1 VWD families recruited into a United Kingdom national study29 were analyzed for the ex4-5del mutation using the Delmap primers at the genomic DNA level, with confirmation by the multiplex assay. Heterozygosity for the deletion was identified in 2 index cases (7:2 and 8:2, Table 1) in whom no candidate VWF mutation had previously been identified. The families of these index cases (families 7 and 8, Table 1) were screened. The mutation was shown to segregate with the type 1 VWD phenotype in family 8. In family 7, heterozygosity for ex4-5del segregated with VWD, with the exception of unaffected person 7:1, suggesting incomplete penetrance of the mutation in this family.

Investigation of the deletion mechanism

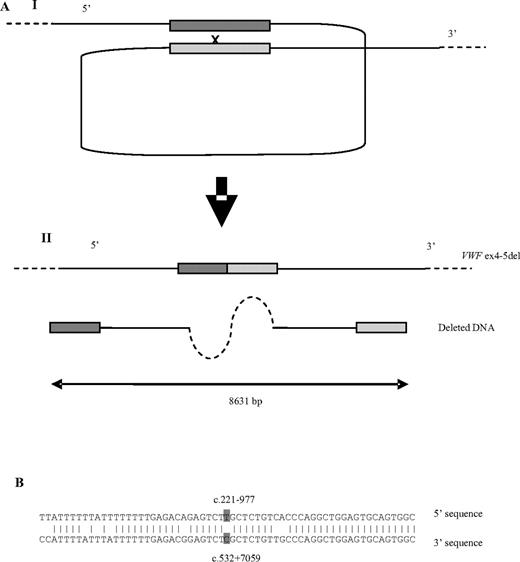

In silico analysis of the DNA sequences adjacent to the deletion breakpoint was performed to investigate the mechanism underlying the deletion. RepeatMasker38 indicated that the 5′ and 3′ breakpoints of the deleted sequence lie within inverted, imperfect AluY elements, which show high homology in the vicinity of the breakpoints (Figure 2). The breakpoints are also situated in the vicinity of topoisomerase II binding and cleavage sites, which are concentrated at sites of nuclear attachment. Further investigation (Mar-Wiz39 ) showed that the 5′ and 3′ breakpoints lie within regions of high Matrix Associated Region potential. These AT-rich regions contain numerous origin of replication patterns and are implicated in the interaction between chromatin and the nuclear matrix.14,42

A possible model for the pathogenesis of the deletion. (Ai) AluY repeats, highlighted in dark gray (5′) and light gray (3′) at the 5′ and 3′ deletion breakpoints line up while attached to the nuclear matrix, followed by a recombination event. This results (Aii) in the deletion of 8631 bp, including exons 4 and 5 from VWF. (B) An 85.2% (52 of 61) homology between the 5′ and 3′ AluY sequences 30 bp on either side of the deletion breakpoints (highlighted in dark gray).

A possible model for the pathogenesis of the deletion. (Ai) AluY repeats, highlighted in dark gray (5′) and light gray (3′) at the 5′ and 3′ deletion breakpoints line up while attached to the nuclear matrix, followed by a recombination event. This results (Aii) in the deletion of 8631 bp, including exons 4 and 5 from VWF. (B) An 85.2% (52 of 61) homology between the 5′ and 3′ AluY sequences 30 bp on either side of the deletion breakpoints (highlighted in dark gray).

Haplotype analysis

Haplotype analysis was performed to investigate the possibility of a founder effect in the patients with the ex4-5del mutation. In the 7 type 3 VWD patients as well as the 2 type 1 VWD index cases and affected family members with this mutation, the deletion segregated with a common VWF haplotype. In the 2 related type 3 VWD patients who were homozygous for the deletion, a second VWF haplotype was observed, in the compound heterozygous state with the common haplotype (Table 2). The second haplotype and common haplotype were identical 5′ to the deletion breakpoint but were different 3′ to this location.

Expression and characterization of recombinant VWF

To determine whether or not the mutant recombinant protein was retained within the cell or was inefficiently secreted, VWF:Ag levels were assayed in cell lysates and in the conditioned media using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Secretion of the rVWF protein from the heterozygous and homozygous ex4-5del transfections was decreased by 86% (P < .001) and 98% (P < .001), respectively, relative to the secretion of the wild-type rVWF protein (VWF:Ag levels for the wild-type, heterozygous, and homozygous mutant were 1.53 ± 0.04 U/mL, 0.21 ± 0.01 U/mL, and 0.03 ± 0.00 U/mL, respectively; n = 5). VWF:RCo levels for the wild-type, heterozygous, and homozygous mutant concentrated media were 1.58 U/mL, 0.52 U/mL, and 0.00 U/mL, respectively. The decrease in recombinant protein (heterozygous and homozygous mutant) in the media did not correspond to an increase in intracellular retention. VWF:Ag levels for the wild-type, heterozygous, and homozygous mutant cell lysates were 0.09 U/mL, 0.08 U/mL, and 0.08 U/mL, respectively. These results demonstrate that the deletion of VWF exons 4 and 5 results in markedly decreased secretion of VWF and indicate the dominant-negative effect of the mutation in the heterozygous state.

To determine the effect of the ex4-5del mutation on VWF multimers, conditioned media from the wild-type, homozygous mutant, and 50:50 heterozygous transfections were concentrated and analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate–agarose gel electrophoresis. A full range of multimers was observed in the media from the heterozygous transfections. Only dimers were observed in the media of the recombinant homozygous mutant protein, indicating that this mutation interferes with the multimerization process.

Control screening

A total of 100 anonymized blood samples received by the laboratory for hereditary hemochromatosis genotyping were screened to confirm that the deletion event observed was a pathogenic mutation and not a polymorphism present in the general population. All of the 200 alleles screened were negative for the ex4-5del mutation.

Discussion

The present study aimed to identify the molecular pathogenesis of type 3 VWD in a cohort of patients from the North West of England by direct sequencing of VWF at the genomic DNA level and of VWF mRNA-derived cDNA. This approach identified homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations consistent with the type 3 VWD phenotype in 19 of 21 patients from 20 unrelated families (M.S.S., A.M.C., P.H.B.B.-M., C.R.M.H., A.M.W., S.K., manuscript submitted). Seven patients were found to have a previously unreported c.221-977_532 + 7059del mutation (ex4-5del), which removed 8631 bp of VWF genomic sequence, including exons 4 and 5. Three of these 7 patients, including 2 from the same family, were homozygous for this mutation, as detected and characterized at the genomic DNA level. The remaining 4 persons were heterozygous for the deletion, which was detected initially at the RNA level only. Three of these 4 persons were compound heterozygous for the deletion and a second VWF mutation, thus explaining their type 3 VWD phenotype. A second VWF mutation to explain the type 3 VWD phenotype has not been identified in the fourth person (patient 2:1, Table 1). Overall, the ex4-5del mutation occurred frequently in our type 3 VWD patients of white origin (7 of 12 persons from 6 unrelated families) but was absent in 9 patients of Asian origin. The prevalence of the deletion among the apparently unrelated type 3 VWD families in our cohort was 8 of 40 alleles (20%) from 20 unrelated families.

The high prevalence of the ex4-5del mutation in our type 3 VWD study population, together with failure to detect heterozygosity for this mutation when genomic DNA was analyzed by standard methods because of the presence of a normal allele, led us to investigate the occurrence of this mutation in 34 unrelated type 1 VWD index cases previously recruited into a United Kingdom national study.29 Heterozygosity for ex4-5del was identified in 2 cases. In both, a type 1 VWD-causative candidate VWF mutation had not been previously identified. Heterozygosity was subsequently identified in other VWD-affected family members of these index cases, suggesting that heterozygosity for this mutation was causative of type 1 VWD in these kindreds. Heterozygosity for ex4-5del was identified in one unaffected person (person 7:1, Table 1), suggesting incomplete penetrance of the mutation. Data were not available to us to indicate whether or not the normal VWF laboratory parameters in this elderly subject may be the result of VWF levels having increased with age.

Since the investigation of the original type 3 and type 1 VWD patient cohorts, we have also identified the ex4-5del mutation in a further 4 persons (Table 1), including compound heterozygosity in a type 3 VWD index case (9:1) and heterozygosity in his possible type 1 VWD affected mother (9:2), heterozygosity in a type 1 VWD affected relative (1:2) of a patient from the original type 3 VWD patient cohort (1:1), and heterozygosity in a newly investigated patient with type 1 VWD (10:1). All 4 of these persons were of white British origin.

Haplotype analysis was performed using a panel of 25 previously described polymorphisms associated with VWF (Table 2). This identified a common haplotype associated with ex4-5del in 5 type 3 VWD patients who were heterozygous for this mutation, 3 homozygous type 3 VWD patients (2 related), 2 heterozygous type 1 VWD-affected family members of type 3 VWD index cases, 3 type 1 VWD index cases heterozygous for the deletion, and a further 4 heterozygous family members from the families of the type 1 VWD index cases. This suggested a common origin of the deletion among these apparently unrelated kindreds. The presence of a second VWF haplotype in 2 related persons (6:1 and 6:2) may indicate that a recombination event has occurred in this family, resulting in the deletion being associated with a different haplotype. To support this suggestion, in these 2 persons, the haplotype 5′ of the deletion was identical to the “common” deletion-associated haplotype, with variance only 3′ of the deletion.

Further analysis is required to examine the prevalence of the ex4-5del mutation in other VWD patient populations, for example, in the Canadian and European type 1 VWD patient cohorts.

Candidate mechanism for the VWF ex4-5del deletion

The 5′ and 3′ breakpoints of the deletion were shown to lie within regions of AluY repetitive elements and in the proximity of topoisomerase II binding and cleavage sites, which are responsible for the splicing of DNA. Alu repeats are the most abundant class of short interspersed repeat elements in the human genome, and they are known to promote unequal homologous recombination. The breakpoints also lie within regions of high matrix association potential, suggesting that the regions may be in close proximity when attached to the nuclear matrix during DNA replication. Taken together, it is probable that the AluY regions line up when attached to the nuclear matrix, causing the formation of a hairpin loop. A further mechanism, eg, an incorrect cleavage and rejoining event mediated by topoisomerase II, may be responsible for the incorrect recombination of the 2 DNA strands either side of the breakpoints and the splicing of the 8631 bp encompassing exons 4 and 5 as well as flanking intronic sequences (Figure 2). There are previous reports of large deletions causing type 3 VWD with a similar Alu-mediated deletion mechanism to that proposed here.13,14

Significance of the deletion in type 1 and type 3 VWD

Type 3 VWD is a severe bleeding disorder inherited in an autosomal recessive manner with reported VWF mutations mostly resulting in a null allele, ie, nonsense, frameshift, and deletion mutations. Despite some previous reports,15,17,43,44 the different inheritance patterns and genetics of types 1 and 3 VWD mean that it is unusual to find a type 3 VWD linked mutation that, in the heterozygous state, is clearly associated with dominant type 1 VWD. The ex4-5del mutation may be expected to have an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern, requiring the presence of the deletion in either the homozygous or compound heterozygous state. However, in association with type 1 VWD, ex4-5del appears to operate in an autosomal dominant fashion with normal VWF multimers, as observed in the type 1 VWD index cases and their affected family members (Table 1). Expression studies have demonstrated an 86% decrease in secretion of VWF from heterozygous transfections compared with secretion of VWF from wild-type cells, providing further evidence of a dominant-negative effect of ex4-5del and the association of this mutation with type 1 VWD.

In conclusion, we have identified and described the investigation of a previously unreported deletion of VWF exons 4 and 5. Expression studies have indicated that this mutation causes markedly decreased secretion and defective multimerization of the resultant mutant VWF protein. The absence of increased intracellular retention of the mutant VWF may be the result of proteasomal degradation of the protein in the cytoplasm, mooted as a possible general mechanism for mutations associated with dominant type 1 VWD.33 The ex4-5del mutation is recurrent among type 3 VWD patients of British white origin and, in the heterozygous form, appears to underlie a proportion of cases of dominant type 1 VWD. Our data indicate that, in the majority of cases, the deletion originates from a single founder event; however, there is evidence for a possible recombination event associating the mutation with a second VWF haplotype. Together with the theoretical mechanism for the deletion, this raises the possibility that ex4-5del may be present in persons of other ethnicities. The deletion described may go undetected using current VWF screening strategies; however, it is readily detected using the PCR-based analysis described herein. Screening for the ex4-5del mutation in other type 1 and type 3 VWD patient populations is required to provide further information on the overall contribution of this mutation to quantitative deficiencies of VWF.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the members of the United Kingdom Hemophilia Center Doctors' Organisation von Willebrand Disease Working Party and other scientists and clinicians who participated in the recent United Kingdom study of the molecular pathogenesis of type 1 VWD,29 index case patient samples from which were among those screened for the VWF exons 4 and 5 deletion described in the current manuscript: S. Brown (London), E. Chalmers (Glasgow), S. Enayat (Birmingham), G. Evans (Canterbury), P. Grundy (Manchester), A. Guilliatt (Birmingham), J. Hanley (Newcastle), F. Hill (Birmingham), D. Keeling (Oxford), K. Khair (London), R. Leisner (London), W. Lester (Birmingham), C. Millar (London), J. Pasi (London), C. Tait (Glasgow), L. Tillyer (Lewisham), and J. Wilde (Birmingham).

Authorship

Contribution: M.S.S. and D.J.B. designed and performed the research, analyzed and interpreted data, and contributed to writing the manuscript; A.M.C. and S.K. designed the research, analyzed and interpreted data, and contributed to writing the manuscript; M.B. designed and performed the expression studies, analyzed and interpreted data, and contributed to writing the manuscript; P.H.B.B.-M., C.R.M.H., and A.M.W. recruited patients and provided clinical information; and P.W.C. recruited patients, provided clinical information, and contributed to writing the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Stephen Keeney, Molecular Diagnostics Centre, Top-Floor Multipurpose Bldg, Manchester Royal Infirmary, Oxford Rd, Manchester, M13 9WL, United Kingdom; e-mail: steve.keeney@cmft.nhs.uk.