Abstract

Endorepellin, the C-terminal domain of perlecan, is a powerful angiogenesis inhibitor. To dissect the mechanism of endorepellin-mediated endothelial silencing, we used an antibody array against multiple tyrosine kinase receptors. Endorepellin caused a widespread reduction in phosphorylation of key receptors involved in angiogenesis and a concurrent increase in phosphatase activity in endothelial cells and tumor xenografts. These effects were efficiently hampered by function-blocking antibodies against integrin α2β1, the functional endorepellin receptor. The Src homology-2 protein phosphatase-1 (SHP-1) coprecipitated with integrin α2 and was phosphorylated in a dynamic fashion after endorepellin stimulation. Genetic evidence was provided by lack of an endorepellin-evoked phosphatase response in microvascular endothelial cells derived from integrin α2β1−/− mice and by response to endorepellin in cells genetically engineered to express the α2β1 integrin, but not in cells either lacking this receptor or expressing a chimera harboring the integrin α2 ectodomain fused to the α1 intracellular domain. siRNA-mediated knockdown of integrin α2 caused a dose-dependent reduction of SHP-1. Finally, the levels of SHP-1 and its enzymatic activity were substantially reduced in multiple organs from α2β1−/− mice. Our results show that SHP-1 is an essential mediator of endorepellin activity and discover a novel functional interaction between the integrin α2 subunit and SHP-1.

Introduction

The development and maintenance of an efficient vascular system is vital for organ function and health in all higher organisms. Angiogenesis is abundant during fetal development but in the adult is a rare process mainly restricted to the female reproductive cycle and wound healing. However, deregulated angiogenesis is a prominent factor in many major diseases such as cancer, diabetes, and ischemia occurring after stroke. Controlled angiogenesis is achieved by interplay of proangiogenic and antiangiogenic factors. Proangiogenic growth factors, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), signal by their respective receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) to stimulate endothelial cell migration and proliferation, whereas angiogenic inhibitors counteract these actions.1 The list of reported negative regulators of angiogenesis is long, ever growing, and truly versatile. Nevertheless, a common theme for many of them is that they are derived from limited proteolysis of extracellular matrix components and that they interact with integrin receptors.2

The angiostatic protein endorepellin, located within the C-terminus of the heparan sulfate proteoglycan perlecan, consists of 3 laminin globular (LG1-3) domains separated by 4 epidermal growth factor-like repeats.3 Endorepellin exerts its activity by a noncanonical cation-independent binding of the LG3 domain to the α2 I domain of the integrin α2β1,4-7 a key receptor regulating angiogenesis.8-10 This triggers a signaling cascade that leads to endothelial cell immobilization primarily because of disassembly of the actin cytoskeleton and disruption of focal adhesions.5 Endorepellin efficiently retards tumor growth by targeting the tumor vasculature.11 Animals deficient in integrin α2β1 fail to respond to systemic delivery of recombinant endorepellin; hence, the integrin α2β1 receptor is indispensable for mediating endorepellin's antiangiogenic effect in vivo.4 Cathepsin L and BMP-1/Tolloid-like metalloproteases can release endorepellin and LG3, respectively.6,12 The growing number of reports identifying LG3 in nearly all body fluids, including urine, blood, and amniotic fluid, further strengthen the concept of an endogenous role for endorepellin LG3 in regulating angiogenesis and perhaps other biologic processes.13-15

Many cellular processes such as survival, proliferation, differentiation, and migration are governed by RTK signaling. On binding with their specific ligand, RTKs dimerize and become autophosphorylated on multiple sites. The phosphorylation status of RTKs is tightly regulated by the activity of kinases and phosphatases. It has become apparent that integrins crosstalk with growth factor receptors to regulate cellular processes, such as endothelial cell migration and proliferation during angiogenesis.16 One way of accomplishing this interaction is by integrin-regulated recruitment of tyrosine phosphatases to growth factor receptors. Endothelial cell attachment to collagen I, which is primarily mediated by the α2β1 receptor, recruits the tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2 to the cytoplasmic tail of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2). This lowers the angiogenic response by inducing dephosphorylation of key tyrosine residues of the receptor.17 However, activation of the integrin β3 subunit promotes angiogenesis by tethering SHP-2 to its cytoplasmic tail, which generates a net increase in VEGFR2 phosphorylation. Signaling by tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 2 (TIMP-2) via the integrin α3β1 dephosphorylates FGFR1 and VEGFR2 in endothelial cells.18 Integrin α3β1 directly interacts with SHP-1, and TIMP-2 stimulation shifts the phosphatase activity from integrin α3β1 to growth factor receptors.18

In the present work we demonstrate that endorepellin evokes a global RTK dephosphorylation by integrin α2β1–mediated activation of the tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1. We show that integrin α2β1 and SHP-1 are physically associated by the cytoplasmic domain of the integrin α2 subunit and provide biochemical and genetic evidence for a key role of SHP-1 in mediating the antiangiogenic activity of endorepellin.

Methods

Antibodies, animals, cells, and other reagents

The following antibodies were used: anti-GAPDH (Advanced Immunochemical), anti–SHP-1 (Millipore Corporation), anti–β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich), anti–integrin α2 I domain (mAb 1998Z) and anti–integrin α5 (mAb 1969; Millipore Corporation), anti–SHP-1, anti–SHP-2, anti-VEGFR2, anti–integrin α1 and α2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti–integrin α1 (mAb 1969; Chemicon International), anti–PY783-PLCγ1 and anti–PLCγ1 (Cell Signaling Technology Inc), and PY20 (BD Biosciences). Secondary antibodies included rhodamine-conjugated goat anti–rabbit IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), HRP-conjugated goat anti–mouse and anti–rabbit (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc), IR-680 goat anti–mouse, and IR-800CW goat anti–rabbit IgG (LI-COR). Rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin, DAPI, and Na3VO4 (Sigma-Aldrich), NSC-87 877 (Calbiochem), rat tail collagen-I (BD Biosciences), and VEGF165 (R&D Systems) were used. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs; Lifeline Cell Technology), passages 1 to 5, were cultured on gelatin. The murine myogenic C2C12 and ureteric bud (UB) cells were maintained as described.19,20 HT-1080 cells were transfected with 2 small interfering RNAs (siRNAs; Ambion) targeting integrin α2 as described.4 HUVECs were transfected with siRNA cocktails targeting SHP-1 (sc29478) or SHP-2 (sc-36 488), and HT1080 with siRNA targeting EphA2 (sc-29 304; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Endorepellin was produced as previously described.3 An Olympus BX51 microscope and a SPOT RT color camera driven by SPOT Advanced Imaging software (Version 4.09; Diagnostics Instruments Inc) was used to acquire fluorescent images with a dry 40× magnification, 0.75 aperture objective. Stained cells were mounted in Vectashield mounting media (Vector Laboratories), and Adobe Photoshop CS3 and ImageJ software were used for image processing. C57Bl/6 wild-type and α2 integrin subunit–deficient mice21 were housed in the pathogen-free facility of Thomas Jefferson University in compliance with regulations of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

Pan phospho-RTK array, immunoblots, immunostaining, and immunoprecipitation

HUVECs, grown in 100 μg/mL collagen–coated dishes, were serum-starved for 1 hour before endorepellin treatment. For integrin blocking experiments, cells were preincubated for 1 hour with various mAbs (10 μg/mL). Cells were lysed, protein was extracted, and RTK membranes were probed following manufacturer's instructions (R&D Systems). Organs from C57Bl/6 wild-type and integrin α2β1−/− mice were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, homogenized, and extracted in RIPA buffer. Proteins were separated by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and electroblotted onto Nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad). The blots were developed with either chemiluminescence or IR-labeled secondary antibodies and detected with the use of Odyssey v2.1 (LI-COR). Cells for immunostaining were fixed for 5 minutes in ice-cold methanol, blocked in 5% BSA-PBS, and then reacted with mouse anti–human SHP-1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Images were acquired by confocal microscopy. Livers from wild-type and α2β1−/− mice were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, cryosectioned, fixed, and permeabilized in ice-cold acetone/0.2% Triton X-100.

For immunoprecipitation, Protein A–Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare) were absorbed with antibodies for 1 hour at 4°C, and precleared cell lysates were added to the beads for 18 hours at 4°C. After extensive washing, the beads were boiled in reducing buffer, and supernatants were separated by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

In vitro kinase assay

HUVECs were stimulated with 10 ng/mL VEGF165 for 5 minutes, lysed in RIPA buffer, and immunoprecipitated with anti-VEGFR2 antibody. The precipitates were washed in TBS-T and incubated with HUVEC lysates from cells treated with endorepellin for 0 to 10 minutes. The beads and lysates were incubated at 37°C for 15 minutes, pelleted, washed, boiled, and then processed for immunoblotting. The blots were probed with PY-20 and rabbit anti–human VEGFR2 and analyzed with the use of Odyssey (LI-COR).

Tyrosine phosphatase and migration assays

Tyrosine phosphatase activity was measured with the use of the Tyrosine-Phosphatase Assay kit (Promega) following the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, cell and tumor extracts precleaned for phosphate were incubated with tyrosine phosphopeptides as substrate. The release of PO4 was normalized on cell protein and was expressed as pmol/mL per minute. Total phosphate content was determined by phosphate standards run in parallel. Phosphopeptide-specific activity was calculated by subtracting the nonspecific activity. The activity of SHP-1 was assessed on SHP-1 immunoprecipitates. Tumor xenograft, adhesion, migration, and cytoskeleton disassembly assays were done as previously described.4 For UB and C2C12 cell migration, self-conditioned media were used as chemoattractants. For PLCγ1 phosphorylation assays, HUVECs were serum-starved for 1 hour with or without the addition of Na3VO4 and NSC-87 877, after which 10 ng/mL VEGF165, in combination with 25nM endorepellin, or 25nM endorepellin alone was added for 5 minutes.

Statistical analyses

All data are expressed as means plus or minus SEMs and were statistically analyzed with the Student t test or paired t test with the Sigma-Stat software 10.0 (SPSS Inc). Probabilities less than .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Endorepellin evokes global dephosphorylation of receptor tyrosine kinases in endothelial cells

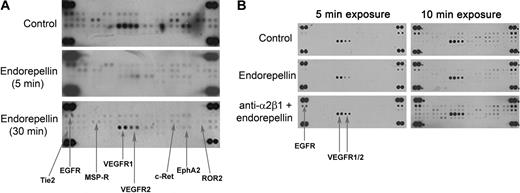

To discover novel pathways affected by endorepellin in endothelial cells, we screened for changes in the phosphorylation status of RTKs after endorepellin stimulation with the use of phosphor-RTK arrays. We found that endorepellin caused a global dephosphorylation of RTKs. This effect was prominent already after a 5-minute treatment and was sustained for up to 30 minutes (Figure 1A; Table 1). Notably, functional block of the integrin α2β1 receptor with the mAb 1998Z abrogated the endorepellin-evoked RTK dephosphorylation (Figure 1B; Table 1). On the contrary, blocking integrin α5β1 did not affect the endorepellin response (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Endorepellin provokes dephosphorylation of multiple RTKs through the integrin α2β1 receptor. (A) Antibody array recognizing 42 distinct RTKs incubated with HUVEC extracts from cells maintained for 5 and 30 minutes in the absence or presence of endorepellin (100 nM) and probed with anti–phosphotyrosine antibody. HUVECs grown on collagen type I were serum-starved for 1 hour before the addition of endorepellin. The major affected RTKs are labeled and indicated by arrows. (B) Experiment as in panel A, with the exception of that the lower panel was preincubated for 1 hour with 10 μg/mL integrin α2 blocking antibody 1998z prior endorepellin stimulation (100nM) for 5 minutes. Different exposures of the membranes (2 and 5 minutes) are shown for easier visualization of changes. Control represents extract from untreated serum-starved HUVECs.

Endorepellin provokes dephosphorylation of multiple RTKs through the integrin α2β1 receptor. (A) Antibody array recognizing 42 distinct RTKs incubated with HUVEC extracts from cells maintained for 5 and 30 minutes in the absence or presence of endorepellin (100 nM) and probed with anti–phosphotyrosine antibody. HUVECs grown on collagen type I were serum-starved for 1 hour before the addition of endorepellin. The major affected RTKs are labeled and indicated by arrows. (B) Experiment as in panel A, with the exception of that the lower panel was preincubated for 1 hour with 10 μg/mL integrin α2 blocking antibody 1998z prior endorepellin stimulation (100nM) for 5 minutes. Different exposures of the membranes (2 and 5 minutes) are shown for easier visualization of changes. Control represents extract from untreated serum-starved HUVECs.

Effects of endorepellin on tyrosine phosphorylation of various tyrosine kinase receptors in human endothelial cells

| Receptor . | Endorepellin-evoked Tyr phosphorylation over controls* . | P . | Anti-α2β1 + endorepellin† . | P . | Reported function . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EGFR | 0.328 ± 0.017 | < .001 | 1.10 ± 0.23 | .505 | Migration, proliferation |

| EphA2 | 0.144 ± 0.056 | < .001 | 0.95 ± 0.08 | .899 | Guidance of cell migration |

| MSP-R | 0.422 ± 0.16 | .035 | 1.16 ± 0.04 | .885 | Migration, proliferation, tubular morphogenesis |

| c-Ret | 0.270 ± 0.096 | .017 | 0.99 ± 0.16 | .829 | Survival, proliferation |

| ROR2 | 0.207 ± 0.073 | .008 | 1.51 ± 0.34 | .232 | Growth |

| Tie2 | 0.212 ± 0.063 | .001 | 1.13 ± 0.15 | .712 | Promotion of angiogenesis |

| VEGFR1 | 0.521 ± 0.029 | < .001 | 1.19 ± 0.20 | .606 | Migration, proliferation, tubular morphogenesis |

| VEGFR2 | 0.441 ± 0.036 | < .001 | 1.08 ± 0.18 | .932 | Migration, proliferation, tubular morphogenesis |

| Receptor . | Endorepellin-evoked Tyr phosphorylation over controls* . | P . | Anti-α2β1 + endorepellin† . | P . | Reported function . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EGFR | 0.328 ± 0.017 | < .001 | 1.10 ± 0.23 | .505 | Migration, proliferation |

| EphA2 | 0.144 ± 0.056 | < .001 | 0.95 ± 0.08 | .899 | Guidance of cell migration |

| MSP-R | 0.422 ± 0.16 | .035 | 1.16 ± 0.04 | .885 | Migration, proliferation, tubular morphogenesis |

| c-Ret | 0.270 ± 0.096 | .017 | 0.99 ± 0.16 | .829 | Survival, proliferation |

| ROR2 | 0.207 ± 0.073 | .008 | 1.51 ± 0.34 | .232 | Growth |

| Tie2 | 0.212 ± 0.063 | .001 | 1.13 ± 0.15 | .712 | Promotion of angiogenesis |

| VEGFR1 | 0.521 ± 0.029 | < .001 | 1.19 ± 0.20 | .606 | Migration, proliferation, tubular morphogenesis |

| VEGFR2 | 0.441 ± 0.036 | < .001 | 1.08 ± 0.18 | .932 | Migration, proliferation, tubular morphogenesis |

The values represent the relative levels of the phosphorylation status of individual tyrosine kinase receptors (mean ± SEM) evoked by a 5-minute treatment with endorepellin compared with vehicle-treated HUVECs (n ≥ 4). P values were calculated with the Student t test.

The values represent the phosphorylation status of individual tyrosine kinase receptors (mean ± SEM) after coincubation with a function-blocking antibody (mAb 1998z directed toward the α2 subunit of the α2β1 integrin) and endorepellin compared with vehicle-treated HUVECs (n ≥ 4). P values were calculated with the Student t test.

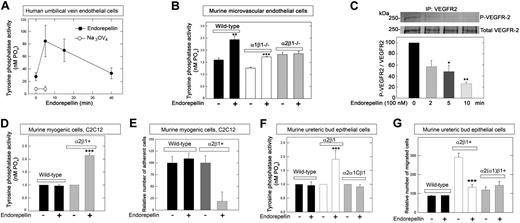

The rapid dephosphorylation in endothelial cells suggested that endorepellin might induce the enzymatic activity of a tyrosine phosphatase. Thus, we investigated endorepellin-evoked changes in the general tyrosine phosphatase activity in HUVECs grown on collagen. The results showed a rapid and dynamic profile of total tyrosine phosphatase activity, which peaked at 5 minutes and returned to basal levels after 30 minutes (Figure 2A). This process was completely blocked by the general tyrosine phosphatase inhibitor Na3VO4 (Figure 2A).

Endorepellin evokes tyrosine phosphatase activity in an integrin α2β1–dependent manner. (A) Endorepellin induces dynamic changes in the ability of HUVECs to dephosphorylate phospho-tyrosine peptides. Cells were incubated with Na3VO4 (1μM) 1 hour before endorepellin stimulation. (B) Tyrosine phosphatase activity of primary cultures of pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells isolated from either wild-type, α1β1−/−, or α2β1−/− mice. The cells were exposed for 5 minutes to endorepellin (25nM). Means ± SEMs (n = 3); **P < .01, ***P < .001. (C) An in vitro kinase assay showing that endorepellin induces a dynamic activation of enzymes responsible for VEGFR2 dephosphorylation. Immunoprecipitated phosphorylated VEGFR2 was exposed to lysates from HUVECs before being treated with endorepellin (100 nM) for the indicated time. Means ± SEMs of the relative VEGFR2 phosphorylation compared with time point 0 (n = 3); *P < .05, **P < .01. (D) Relative tyrosine phosphatase activity of wild-type or α2β1+ C2C12 cells after a 5-minute incubation with endorepellin (25nM). Means ± SEMs (n = 3); ***P < .001. (E) Adhesion of wild-type or α2β1+ C2C12 to collagen after a 30-minute incubation with endorepellin (25nM). Mean number of cells ± SEM (n = 3); ***P < .001. (F) Relative tyrosine phosphatase activity of murine UB epithelial cells after a 5-minute exposure to endorepellin (25nM). These cells include wild-type cells, which express undetectable levels of collagen-binding integrins, cells expressing the α2β1+, and cells expressing a chimeric integrin composed of the ectomembrane and transmembrane domains of the α2 subunit fused to the intracellular domain of the α1 subunit, designated α2(α1)β1. Means ± SEMs (n = 3); ***P < .001. (G) Conditioned medium-directed migration through collagen of wild-type, α2β1+, and α2(α1)β1 UB cells after a 20-minute exposure to endorepellin (25nM). Mean number of migrated cells ± SEM (n = 3); ***P < .001.

Endorepellin evokes tyrosine phosphatase activity in an integrin α2β1–dependent manner. (A) Endorepellin induces dynamic changes in the ability of HUVECs to dephosphorylate phospho-tyrosine peptides. Cells were incubated with Na3VO4 (1μM) 1 hour before endorepellin stimulation. (B) Tyrosine phosphatase activity of primary cultures of pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells isolated from either wild-type, α1β1−/−, or α2β1−/− mice. The cells were exposed for 5 minutes to endorepellin (25nM). Means ± SEMs (n = 3); **P < .01, ***P < .001. (C) An in vitro kinase assay showing that endorepellin induces a dynamic activation of enzymes responsible for VEGFR2 dephosphorylation. Immunoprecipitated phosphorylated VEGFR2 was exposed to lysates from HUVECs before being treated with endorepellin (100 nM) for the indicated time. Means ± SEMs of the relative VEGFR2 phosphorylation compared with time point 0 (n = 3); *P < .05, **P < .01. (D) Relative tyrosine phosphatase activity of wild-type or α2β1+ C2C12 cells after a 5-minute incubation with endorepellin (25nM). Means ± SEMs (n = 3); ***P < .001. (E) Adhesion of wild-type or α2β1+ C2C12 to collagen after a 30-minute incubation with endorepellin (25nM). Mean number of cells ± SEM (n = 3); ***P < .001. (F) Relative tyrosine phosphatase activity of murine UB epithelial cells after a 5-minute exposure to endorepellin (25nM). These cells include wild-type cells, which express undetectable levels of collagen-binding integrins, cells expressing the α2β1+, and cells expressing a chimeric integrin composed of the ectomembrane and transmembrane domains of the α2 subunit fused to the intracellular domain of the α1 subunit, designated α2(α1)β1. Means ± SEMs (n = 3); ***P < .001. (G) Conditioned medium-directed migration through collagen of wild-type, α2β1+, and α2(α1)β1 UB cells after a 20-minute exposure to endorepellin (25nM). Mean number of migrated cells ± SEM (n = 3); ***P < .001.

Integrin α2β1 is required for endorepellin induction of tyrosine phosphatase activity

To address the genetic requirement of integrin α2β1 for the endorepellin-induced phosphatase response, we isolated lung microvascular endothelial cells from wild-type mice and from mice with a targeted disruption of either integrin α122 or α221 gene, thereby lacking a functional integrin α1β1 or α2β1 gene, respectively. After a 5-minute exposure to recombinant human endorepellin (25nM) there was an approximate 40% increase in tyrosine phosphate activity in both wild-type and integrin α1β1−/− microvascular endothelial cells but no changes in the integrin α2β1−/− cells (Figure 2B).

To ascertain that the elicited phosphatase activation was indeed responsible for the global RTK dephosphorylation, we performed a nonradioactive in vitro kinase assay. Phosphorylated VEGFR2 was immunoprecipitated and treated for 15 minutes with HUVEC lysates collected after progressive endorepellin exposure. The results showed a dynamic and significant decrease in the VEGFR2 phosphorylation (Figure 2C). This indicates that the endorepellin-evoked phosphatase activity translates into dephosphorylation of RTKs in agreement with the phospho-RTK arrays.

To further establish that the unresponsiveness of the α2β1−/− cells was due to the lack of this receptor and not to off-target consequences of gene deletion, we used (1) murine myogenic C2C12 cells that lack classical collagen-binding integrins (supplemental Figure 2) and therefore attach poorly to collagen,19 and (2) C2C12 cells stably expressing either the human integrin α2 (α2β1+)19 or α1 subunit (α1β1+).23 We determined that α1β1+ and α2β1+ C2C12 cells expressed their transgenes at comparable levels (supplemental Figure 2B). After a 5-minute challenge with recombinant endorepellin, there was a doubling in the general tyrosine phosphatase activity in α2β1+ cells, but not in wild-type (Figure 2D; P < .001) or α1β1+ (not shown) cells. Endorepellin efficiently blocked adhesion to collagen I in integrin α2β1+ cells but not in wild-type (Figure 2E; P < .001) or α1β1+ (not shown) cells. These results indicate that endorepellin-evoked activation of tyrosine phosphatases requires the integrin α2β1 receptor.

The tyrosine phosphatase response could be mediated by a unique domain within the cytoplasmic domain of the integrin α2 chain or by the conserved juxta-membrane motif of the α chains. Alternatively, the activation could be mediated by the intracellular domain of the integrin β1 chain. To address this issue, we used murine UB epithelial cells. These cells, which naturally express negligible levels of integrin α2β1 (supplemental Figure 2A), were stably transfected with human full-length integrin α2, or a chimeric construct consisting of the ectomembrane and transmembrane domains of the integrin α2 subunit fused to the cytoplasmic tail of the integrin α1 subunit, designated α2(α1)β1.20 Only cells carrying the complete α2β1 exhibited an increase in total tyrosine phosphatase activity (Figure 2F; P < .001). Notably, the cytoplasmic domain of the α2 chain was indispensable insofar as the cells harboring chimeric integrin α2(α1)β1 did not respond to endorepellin (Figure 2F). Consequently, only the cells expressing full-length integrin α2 exhibited a delayed migration evoked by endorepellin (Figure 2G). The unresponsiveness of the α2(α1)β1 expressors was not caused by low attachment to collagen because both groups attached equally well to this substrate (supplemental Figure 3). Our results indicate that the intracellular domain of the integrin α2 subunit is fundamental for the endorepellin-mediated boost in tyrosine phosphatase activity and rule out the possibility that the phosphatase response is solely dependent on the integrin β1 subunit or the integrin α-chain common motif.

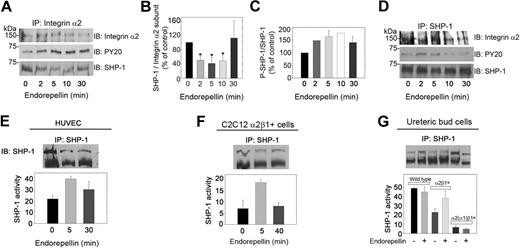

Integrin α2β1 is physically and functionally linked to the tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1

The rapid increase in tyrosine phosphatase activity suggested that the integrin α2β1 receptor might be directly linked to a tyrosine phosphatase. To this end, cell lysates from HUVECs stimulated with endorepellin up to 30 minutes were immunoprecipitated with antibodies against the integrin α2 subunit. HUVECs grown on collagen strongly expressed integrin α2 (supplemental Figure 2C). Two different rabbit polyclonal antibodies were used in the immunoprecipitation analyses, and both antibodies coimmunoprecipitated an approximate 70-kDa band detected with antibodies against phosphotyrosine (Figure 3A). Because we discovered that endorepellin activates the approximate 70-kDa tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1 in collagen-stimulated platelets,24 we probed the immunoprecipitated with an antibody specific for SHP-1. We found that the 70-kDa band was indeed SHP-1 (Figure 3A) and that SHP-1 underwent a rapid and dynamic change in both association with the integrin α2 subunit (Figure 3B) and in phosphorylation (Figure 3C). Moreover, we were able to pull down the α2 subunit with an anti–SHP-1 antibody (Figure 3D), further supporting a close interaction between the 2 proteins. Similar results were obtained with a different anti–SHP-1 antibody (not shown). Total SHP-1 was phosphorylated in the same dynamic fashion as that of the integrin α2-associated fraction, albeit at a lower level (Figure 3D).

Integrin α2β1 is intimately associated with SHP-1. (A) Total HUVEC lysates from cells grown on collagen and stimulated with 25 nM endorepellin for 0, 2, 5, 10, or 30 minutes were immunoprecipitated (IP) with an integrin α2 antibody and immunoblotted (IB) with antibodies against integrin α2, phosphotyrosine residues (PY20), or SHP-1. (B) Quantification of SHP-1 associated with the integrin α2 subunit from experiments as shown in panel A. Means ± SEMs (n = 3); *P < .05. (C) Quantification of phosphorylated SHP-1. Means ± SEMs (n = 3). (D) Cell lysates treated as in panel A were immunoprecipitated with SHP-1 and probed for integrin α2, SHP-1, and phosphotyrosine. (E) Tyrosine phosphatase activity of immunoprecipitated SHP-1 from HUVECs treated with endorepellin (25 nM) for the indicated time intervals. The values in the bottom panel represent means ± SEMs (n = 3). (F-G) Immunoprecipitation of SHP-1 in C2C12 and UB cells with the designated genotypes after endorepellin treatment (25 nM) for 0, 5, and 40 minutes (F) and for 5 minutes (G). The values in the bottom panel represent means ± SEMs (n = 3).

Integrin α2β1 is intimately associated with SHP-1. (A) Total HUVEC lysates from cells grown on collagen and stimulated with 25 nM endorepellin for 0, 2, 5, 10, or 30 minutes were immunoprecipitated (IP) with an integrin α2 antibody and immunoblotted (IB) with antibodies against integrin α2, phosphotyrosine residues (PY20), or SHP-1. (B) Quantification of SHP-1 associated with the integrin α2 subunit from experiments as shown in panel A. Means ± SEMs (n = 3); *P < .05. (C) Quantification of phosphorylated SHP-1. Means ± SEMs (n = 3). (D) Cell lysates treated as in panel A were immunoprecipitated with SHP-1 and probed for integrin α2, SHP-1, and phosphotyrosine. (E) Tyrosine phosphatase activity of immunoprecipitated SHP-1 from HUVECs treated with endorepellin (25 nM) for the indicated time intervals. The values in the bottom panel represent means ± SEMs (n = 3). (F-G) Immunoprecipitation of SHP-1 in C2C12 and UB cells with the designated genotypes after endorepellin treatment (25 nM) for 0, 5, and 40 minutes (F) and for 5 minutes (G). The values in the bottom panel represent means ± SEMs (n = 3).

Integrin α subunits bear sequence similarities in their cytoplasmic juxta-membrane region that diverge into unique motives closer to their C-termini. To determine whether the interaction of SHP-1 with the integrin α2 was rather special for this subunit, we performed coimmunoprecipitation assays with C2C12 cells expressing either α1β1 or α2β1. In the α1β1+ cells, integrin α1 and SHP-1 did not coprecipitate, whereas in the α2β1+ cells, SHP-1 and integrin α2 readily coprecipitated (supplemental Figure 4). This suggests that the interaction with SHP-1 is not general for all α subunits but a more specialized event for the α2 subunit.

Having established a physical link between SHP-1 and the integrin α2β1, we examined if SHP-1 could account for the increase in phosphatase activity after endorepellin treatment. We immunoprecipitated SHP-1 from endorepellin-stimulated HUVECs and measured the ability of the immunoprecipitated proteins to dephosphorylate tyrosine peptides. SHP-1 was activated in a transient manner (Figure 3E), mimicking the kinetics of total tyrosine phosphatase activity and the phosphorylation of integrin α2-linked SHP-1. To test whether the endorepellin-evoked SHP-1 activation was a more general phenomenon, we extended our studies to include the α2β1-carrying C2C12 and UB cells. SHP-1 was rapidly activated by endorepellin in cells expressing full-length integrin α2 (Figure 3F-G).

Collectively, these results show that SHP-1 activation triggered by a specific interaction between soluble endorepellin and the integrin α2β1 receptor contributes significantly to the overall increase in tyrosine phosphatase activity in endothelial cells and in cells de novo expressing this integrin.

Endorepellin signaling induces translocation of SHP-1 into the nuclei

SHP-1 can translocate into the nuclei25 where it can regulate transcription of early response genes.26 We tested wild-type and integrin α1- and α2-transfected C2C12 cells, which show high expression of SHP-1. Endorepellin caused a rapid SHP-1 translocation from the plasma membrane to the nuclei in α2β1+ cells (supplemental Figure 5A-B). In contrast, no differences in SHP-1 subcellular distribution were seen in either wild-type or α1β1+ cells (supplemental Figure 5A). Imaging quantification showed a statistically significant shift of SHP-1 to the nuclei in integrin α2β1+ cells after the addition of endorepellin (supplemental Figure 5C; P < .001). In addition, biochemical analyses of separated cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions also showed this shift (supplemental Figure 5D-E). Thus, endorepellin evokes not only SHP-1 phosphatase activity but also its translocation into the nuclei, where it presumably will affect transcriptional activity of early response genes.

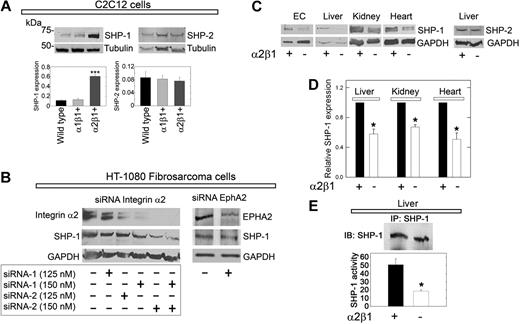

SHP-1 expression is stabilized by integrin α2β1

In preliminary studies, we noticed that α2β1+ C2C12 cells showed stronger expression of SHP-1 than either wild-type or α1β1+ cells. We discovered that de novo expression of the integrin α2 subunit caused a marked increase in SHP-1 protein levels (Figure 4A). In contrast, introduction of the α1 subunit did not noticeably change SHP-1 content (Figure 4A). These changes were unique for SHP-1, because SHP-2 was not altered (Figure 4A), and were not due to clonal selection insofar as the transgenic cells are polyclonal in nature.

SHP-1 protein expression is stabilized by the integrin α2β1 receptor. (A) Immunoblots of total cell lysates from C2C12 cells of the designated genotype, probed for either SHP-1 or SHP-2. Note the marked increase in SHP-1 expression in α2β1+ cells. Bar graphs represent mean ± SEM of the SHP-1 or SHP-2 expression normalized to tubulin (n ≥ 3); ***P < .001. (B) Effective knockdown of integrin α2 expression in HT-1080 cells (left) using a combination of 2 validated siRNAs targeting different regions of α2 mRNA. The expression of integrin α2 and SHP-1 resulting from each siRNA concentration treatment was analyzed by immunoblotting with GAPDH as a loading control. (Right) Knockdown of EphA2. Note that knockdown of integrin α2 drastically reduces the SHP-1 levels, whereas depletion of EphA2 has no effects. (C) Total SHP-1 levels in cell lysates from mouse pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells (ECs) or whole organ lysates as indicated from wild-type or α2β1−/− mice. At the far right, liver from wild-type or α2β1−/− mice probed for SHP-2. (D) Quantification of the SHP-1 expression in organs from 5 different wild-type or α2β1−/− mice. Means ± SEMs; *P < .05. (E) Tyrosine phosphatase activity of immunoprecipitated SHP-1 from livers derived from wild-type or α2β1−/− mice. The values in the bottom panel represent means ± SEMs (n = 3); *P < .05.

SHP-1 protein expression is stabilized by the integrin α2β1 receptor. (A) Immunoblots of total cell lysates from C2C12 cells of the designated genotype, probed for either SHP-1 or SHP-2. Note the marked increase in SHP-1 expression in α2β1+ cells. Bar graphs represent mean ± SEM of the SHP-1 or SHP-2 expression normalized to tubulin (n ≥ 3); ***P < .001. (B) Effective knockdown of integrin α2 expression in HT-1080 cells (left) using a combination of 2 validated siRNAs targeting different regions of α2 mRNA. The expression of integrin α2 and SHP-1 resulting from each siRNA concentration treatment was analyzed by immunoblotting with GAPDH as a loading control. (Right) Knockdown of EphA2. Note that knockdown of integrin α2 drastically reduces the SHP-1 levels, whereas depletion of EphA2 has no effects. (C) Total SHP-1 levels in cell lysates from mouse pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells (ECs) or whole organ lysates as indicated from wild-type or α2β1−/− mice. At the far right, liver from wild-type or α2β1−/− mice probed for SHP-2. (D) Quantification of the SHP-1 expression in organs from 5 different wild-type or α2β1−/− mice. Means ± SEMs; *P < .05. (E) Tyrosine phosphatase activity of immunoprecipitated SHP-1 from livers derived from wild-type or α2β1−/− mice. The values in the bottom panel represent means ± SEMs (n = 3); *P < .05.

To validate the functional role of the integrin α2β1, we used a gene-targeting approach that used validated siRNAs to knockdown the α2 subunit in HT-1080 cells, a fibrosarcoma cell line that expresses high levels of integrin α2β1.4 Expression of the integrin α2-subunit was efficiently blocked by the siRNAs targeting 2 different regions of the α2 mRNA in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 4B). Importantly, SHP-1 levels concurrently declined in these cells (Figure 4B), suggesting that the presence of the integrin α2β1 is required for maintaining the cellular levels of SHP-1. Knockdown of EphA2, a receptor that was strongly dephosphorylated in the initial RTK arrays, had no affect on SHP-1 levels (Figure 4B).

The finding that SHP-1 was dependent on the physical presence of integrin α2β1 prompted us to analyze the requirement of integrin α2β1 for SHP-1 expression in whole organs from wild-type and α2β1−/− mice. SHP-1 levels were significantly (P < .05) reduced by 30% to 60% in the integrin α2β1−/− organs (Figure 4C-D). This was also true for the microvascular endothelial cells isolated from the lungs of integrin α2β1−/− mice (Figure 4C). Again, SHP-2 levels were not changed in these mice, indicating a unique interaction between integrin α2 and SHP-1.

Liver displayed a specific staining for integrin α2 (supplemental Figure 6A-B). Further, SHP-1 colocalized with integrin α2 at the cell surface (supplemental Figure 6C-E). Free cytoplasmic SHP-1 exists predominantly in a folded “inactive” conformation.26 Thus, we hypothesized that depletion of a potential interaction partner such as the integrin α2 subunit could potentially cause a loss of SHP-1 pool associated with the plasma membrane. Confocal analysis showed that SHP-1 was located in hepatocyte nuclei, in accordance with previous studies,27 and further showed a loss of plasma membrane–associated SHP-1 in α2β1−/− livers (supplemental Figure 6F-G). Accordingly, we measured the tyrosine phosphatase activity in immunoprecipitated SHP-1 from wild-type and integrin α2β1−/− hepatic tissue. In integrin α2β1 null livers (n = 3) SHP-1 activity was reduced by approximately 65% compared with integrin α2β1–competent livers (Figure 4E).

Our results suggest that SHP-1/α2β1 interaction is vital for maintaining both the physical presence and the functionality of the phosphatase.

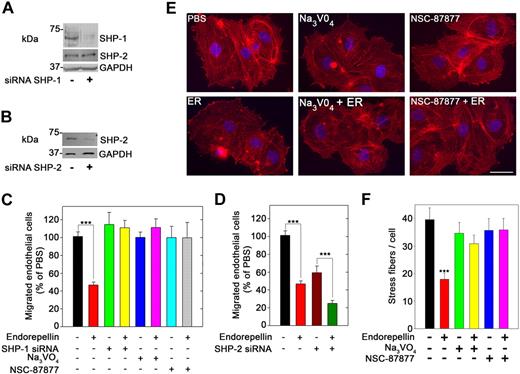

Inhibition of tyrosine phosphatases blocks endorepellin angiostatic activity

Next, we down-regulated SHP-1 expression in HUVECs using a mixture of 3 validated siRNAs directed toward human SHP-1 (Figure 5A). In VEGF165-driven migration assays, endorepellin significantly inhibited endothelial cell migration through collagen (Figure 5C; P < .001). Endorepellin activity was also abrogated by Na3VO4 (1μM), a general tyrosine phosphatase inhibitor, and NSC-87 877 (1μM), a specific inhibitor of SHP-1/2 activity28 (Figure 5C). Preincubation of HUVECs with either Na3VO4 or NSC-87877 (both at 1μM) completely blocked endorepellin-evoked phosphorylation of SHP-1 (data not shown). In contrast, PP2-mediated block of Src, a small tyrosine kinase implicated in integrin-mediated activation of tyrosine phosphatases and phosphorylation of FAK, did not affect the endorepellin-induced block of migration (data not shown). Knockdown of SHP-2 (Figure 5B) caused a general delay in endothelial cell migration in line with previous reports,29 but it did not dampen the response to endorepellin (Figure 5D).

SHP-1 is a crucial mediator of endorepellin antiangiogenic effect. (A) Immunoblot of HUVECs from either mock transfected or transfected with a pool of 3 different SHP-1 siRNAs. Notice the marked knockdown of SHP-1 expression, whereas SHP-2 levels are unaffected. (B) Immunoblot of HUVEC lysates after SHP-2 knockdown by siRNA. (C) Quantification of VEGF-directed migration of HUVECs through collagen type I. Control untreated cells or cells with SHP-1 knockdown, and cells treated with Na3VO4 (1μM) or NSC-87877 (1 μM) were incubated with or without 25nM endorepellin for 20 minutes before commencement of the migration assay. Values represent means ± SEMs (n = 3); ***P < .001. (D) Quantification of migration assays as in panel C. Note that the cells show a slower migration after SHP-2 knockdown, but they still respond to endorepellin; means ± SEMs (n = 3); ***P < .001. (E) Fluorescent images of endothelial cells incubated with rhodamine phalloidin to visualize the actin cytoskeleton (red stress fibers) and DAPI to visualize the nuclei (blue). Notice that the disassembly of actin cytoskeleton after a 20-minute treatment with 25nM endorepellin (ER). This process is blocked by Na3VO4 and NSC-87877. Scale bar, 10 μm. (F) Quantification of the number of actin filaments per cell (n = 60 for each group); ***P < .001.

SHP-1 is a crucial mediator of endorepellin antiangiogenic effect. (A) Immunoblot of HUVECs from either mock transfected or transfected with a pool of 3 different SHP-1 siRNAs. Notice the marked knockdown of SHP-1 expression, whereas SHP-2 levels are unaffected. (B) Immunoblot of HUVEC lysates after SHP-2 knockdown by siRNA. (C) Quantification of VEGF-directed migration of HUVECs through collagen type I. Control untreated cells or cells with SHP-1 knockdown, and cells treated with Na3VO4 (1μM) or NSC-87877 (1 μM) were incubated with or without 25nM endorepellin for 20 minutes before commencement of the migration assay. Values represent means ± SEMs (n = 3); ***P < .001. (D) Quantification of migration assays as in panel C. Note that the cells show a slower migration after SHP-2 knockdown, but they still respond to endorepellin; means ± SEMs (n = 3); ***P < .001. (E) Fluorescent images of endothelial cells incubated with rhodamine phalloidin to visualize the actin cytoskeleton (red stress fibers) and DAPI to visualize the nuclei (blue). Notice that the disassembly of actin cytoskeleton after a 20-minute treatment with 25nM endorepellin (ER). This process is blocked by Na3VO4 and NSC-87877. Scale bar, 10 μm. (F) Quantification of the number of actin filaments per cell (n = 60 for each group); ***P < .001.

To further prove a role for SHP-1 in endorepellin biologic activity, we conducted an actin disassembly assay with HUVECs. A short treatment with endorepellin (25 nM) caused a rapid disassembly of actin cytoskeleton as visualized by phalloidin staining (Figure 5E). Preincubation with either Na3VO4 or NSC-87877 (both at 1μM) rendered the cells resistant to endorepellin's activity (Figure 5E). Quantification of multiple experiments showed that both tyrosine phosphatase inhibitors completely blocked the activity of endorepellin (Figure 5F; P < .001).

Collectively, our data corroborate the hypothesis that SHP-1 activity is crucial for endorepellin-evoked endothelial cell silencing.

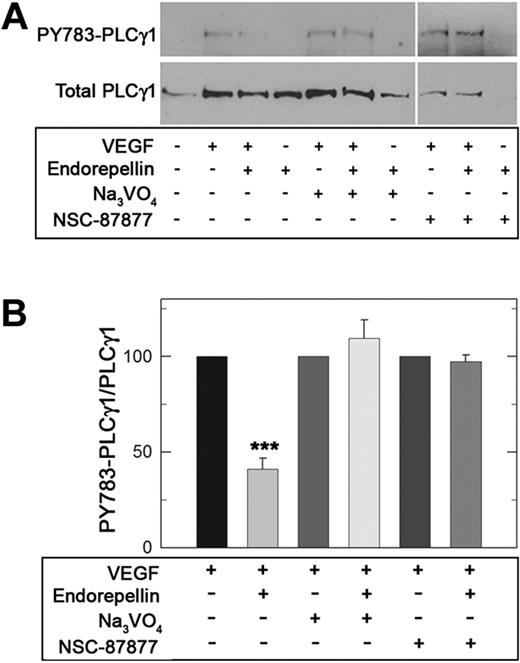

Endorepellin-evoked phosphatase activity modulates RTK downstream signaling

Given endorepellin's promotion of global RTK dephosphorylation, we focused on VEGF/VEGFR2 signaling pathway by examining PLCγ1, a direct downstream target of VEGFR2. When HUVECs were treated for 5 minutes with VEGF165 (10 ng/mL), a robust phosphorylation of PLCγ1 at Tyr783 was observed (Figure 6A). However, concurrent treatment with endorepellin (25nM) significantly reduced PLCγ1 phosphorylation by greater than 50%. Prior silencing of SHP-1 by either Na3VO4 or NSC-87877 completely blocked endorepellin-evoked reduction in PLCγ1 phosphorylation (Figure 6A-B; P < .001).

Endorepellin modulates downstream VEGF/VEGFR2 signaling by engaging SHP-1. (A) Serum-starved HUVECs grown on collagen were stimulated with human recombinant VEGF165 (10 ng/mL) and endorepellin (25nM) either alone or in combination for 5 minutes as marked. When indicated, the cells were pretreated for 1 hour with Na3VO4 (1 μM) or NSC-87877 (1μM). Whole-cell lysates were analyzed on immunoblots for phospho-PLCγ1 or total PLCγ1 content. (B) Quantification of phospho-PLCγ1 normalized on total PLCγ1. Values represent means ± SEMs (n = 3); ***P < .001.

Endorepellin modulates downstream VEGF/VEGFR2 signaling by engaging SHP-1. (A) Serum-starved HUVECs grown on collagen were stimulated with human recombinant VEGF165 (10 ng/mL) and endorepellin (25nM) either alone or in combination for 5 minutes as marked. When indicated, the cells were pretreated for 1 hour with Na3VO4 (1 μM) or NSC-87877 (1μM). Whole-cell lysates were analyzed on immunoblots for phospho-PLCγ1 or total PLCγ1 content. (B) Quantification of phospho-PLCγ1 normalized on total PLCγ1. Values represent means ± SEMs (n = 3); ***P < .001.

To determine the generality of endorepellin engagement of SHP-1 on tyrosine phosphorylation, we analyzed the total tyrosine phosphorylation status of endothelial cells after a 5-minute exposure to endorepellin. Endorepellin globally but specifically reduced tyrosine phosphorylation, and these effects could be blocked by Na3VO4 or NSC-87877 (supplemental Figure 7A-B).

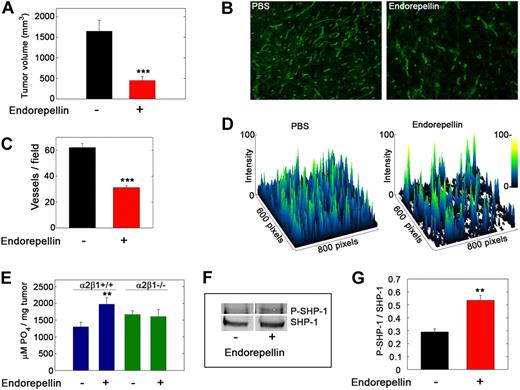

Endorepellin activates SHP-1 in tumor xenografts in vivo

We previously showed that endorepellin functions as an antitumor agent by specifically suppressing tumor angiogenesis.4,11 To translate our in vitro findings into a more clinically relevant setting, we inoculated C57Bl/6 mice with syngeneic Lewis lung carcinoma cells. The mice were treated with PBS or endorepellin by intraperitoneal injections on alternate days after the tumors became palpable. Endorepellin significantly reduced tumor burden (Figure 7A) and microvascular density (Figure 7B-D). Notably, endorepellin evoked a significant increase in total tyrosine phosphatase activity in the tumor xenografts of wild-type mice but failed to do so in the tumor xenografts generated in integrin α2β1−/− mice (Figure 7E). Immunoprecipitated SHP-1 from tumor lysates showed a significant increase in tyrosine phosphorylation from tumors that had received endorepellin (Figure 7F-G). These findings indicate that the host endothelial cells are key mediators of the phosphatase response and that endorepellin is able to activate SHP-1 in vivo.

Endorepellin activates tyrosine phosphatases in tumor xenografts in vivo. (A) Tumor volume at day 19 of Lewis lung carcinoma xenografts in C57Bl/6 after PBS or endorepellin (100 μg/mice) treatment on alternate days. Values represent means ± SEMs (n = 8). (B) Fluorescence images of cryosections of Lewis lung carcinoma tumor xenografts treated as indicated and stained for the vascular marker CD31. (C) Quantification of vessels per field. Values represent the mean ± SEM (n = 40 each). (D) Surface plots of the images in panel B showing that the number of vessels is drastically reduced on endorepellin treatment. (E) Analysis of the total tyrosine phosphatase activity in the tumor extracts. Note the absence of a response to endorepellin in tumors from α2β1−/− mice. (F) Representative immunoblots of immunoprecipitated SHP-1 in Lewis lung carcinoma xenografts from wild-type mice, probed with PY20 for tyrosine phosphorylation or with SHP-1. (G) Quantification of blots as in panel C with the Odyssey image software (LI-COR). Values represent the mean ± SEM (n = 3); **P < .01.

Endorepellin activates tyrosine phosphatases in tumor xenografts in vivo. (A) Tumor volume at day 19 of Lewis lung carcinoma xenografts in C57Bl/6 after PBS or endorepellin (100 μg/mice) treatment on alternate days. Values represent means ± SEMs (n = 8). (B) Fluorescence images of cryosections of Lewis lung carcinoma tumor xenografts treated as indicated and stained for the vascular marker CD31. (C) Quantification of vessels per field. Values represent the mean ± SEM (n = 40 each). (D) Surface plots of the images in panel B showing that the number of vessels is drastically reduced on endorepellin treatment. (E) Analysis of the total tyrosine phosphatase activity in the tumor extracts. Note the absence of a response to endorepellin in tumors from α2β1−/− mice. (F) Representative immunoblots of immunoprecipitated SHP-1 in Lewis lung carcinoma xenografts from wild-type mice, probed with PY20 for tyrosine phosphorylation or with SHP-1. (G) Quantification of blots as in panel C with the Odyssey image software (LI-COR). Values represent the mean ± SEM (n = 3); **P < .01.

Discussion

In the search for novel pathways affected by endorepellin, we discovered that endorepellin provokes a global dephosphorylation of several RTKs. This effect is dependent on the presence of the integrin α2β1, the principal perlecan receptor on endothelial cells.4 RTK phosphorylation levels after ligand engagement are determined by autophosphorylation or phosphorylation of the receptor by other protein kinases and by dephosphorylation by tyrosine phosphatases. Integrins in general16 and collagen-binding integrins in particular17,30 regulate tyrosine phosphatases. Endorepellin causes a rapid activation of the tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1. SHP-1 was first considered to be a phosphatase of hematopoietic cells, but it is now known that its expression is wider than originally proposed26 and that SHP-1 acts as a modulator of blood vessel growth.18,31,32 In endothelial cells, SHP-1 readily coimmunoprecipitates with integrin α2, and, on endorepellin stimulations, SHP-1 becomes phosphorylated and detaches form the α2β1 receptor complex. Pretreatment with the general tyrosine phosphatase inhibitor Na3VO4, SHP-1/2 inhibitor NSC-87877, or siRNA-mediated genetic silencing of SHP-1 causes unresponsiveness to endorepellin. Thus, SHP-1 is an essential mediator of endorepellin's silencing effect on the endothelium.

Endorepellin shares the ability to activate SHP-1 with the well-characterized antiangiogenic agent TIMP-2. TIMP-2 exerts its activity by the integrin α3β1 receptor by engaging SHP-1 in its signaling cascade. The activated SHP-1 dephosphorylates the key angiogenic regulatory RTKs VEGFR2 and FGFR1,18,33 thereby attenuating the growth factors' downstream signaling and causing growth arrest of the endothelium.18,34 Consequently, angiogenic responses to FGF2 and VEGF in Shp1-deficient mice are resistant to TIMP-2 inhibition.34 TNF-α also activates SHP-1 in endothelial cells and thereby limits VEGFR2 signaling.35 Apart from VEGFR2 and FGFR1, SHP-1 has also been linked to the dephosphorylation of multiple other RTKs, eg, RET, EGFR, and PDGFR.36 This is in agreement with the global RTK dephosphorylation evoked by endorepellin treatment.

We previously reported that, in endothelial cells, endorepellin evokes a rapid increase in the intracellular cAMP levels, which in turn activates cAMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA), a required pathway for endorepellin's angiostatic activity.5 The endorepellin-evoked activity is in sharp contrast to endothelial response to collagen I insofar as collagen I–induced capillary morphogenesis is mediated by an integrin α2β1–dependent suppression of intracellular cAMP levels and PKA activity.37 TIMP-2 also induces a rapid and substantial increase in cAMP levels and concurrent activation of cAMP-dependent PKA in microvascular endothelial cells, fibroblasts, as well as in several transformed cells.33,36,38 Interestingly, SHP-1 has been indirectly linked to PKA activation because tyrosine phosphatases are crucial for TIMP-2–induced phosphorylation of PKA targets.33 PKA can phosphorylate serine residues at the C-terminus of SHP-1; this reduces the activity of SHP-1, thereby creating a potential autoregulatory loop,32,39 a mechanism that could potentially occur in the case of endorepellin and TIMP-2 signaling.

The binding site of collagen and endorepellin must be closely localized or overlapping on the integrin α2β1, because both ligands show affinity for the α2 I domain.4 How can 2 closely interacting ligands for the same receptor elicit almost opposite responses? It is possible that endorepellin and collagen interaction with the integrin α2β1 results in differential changes in the conformation of the receptor that differently exposes intracellular docking sites, which could account for the disparate biologic response.

VEGF signaling through the VEGFR2 is modulated by Src activation of SHP-1 that is already attached to the receptor.32 It is important to notice that endorepellin's effect on endothelial cells and platelets is Src independent.5,24 Further, there is a dynamic decrease in the SHP-1 associated with integrin α2β1 after endorepellin signaling, suggesting that “activated” SHP-1 translocates from the integrin α2β1 receptor to the affected RTKs. In this regard endorepellin shares a similar mode of action with TIMP-2.18

SHP-1 can dephosphorylate Tyr996, Tyr1059, and Tyr1175 on VEGFR2.32 Phosphorylation of Tyr1175 in VEGFR2 is necessary for the subsequent activation of the direct downstream target PLCγ1.32 Endorepellin reduces PLCγ1 phosphorylation after VEGF stimulation, and this effect can be counteracted by the blockade of SHP-1 activity. This suggests that endorepellin activation of SHP-1 has direct consequences on growth factor downstream signaling, either by SHP-1 dephosphorylating RTKs or by physically interacting with their downstream targets.40 Because SHP-1 does not affect Tyr951, a key residue regulating migration, we conclude that the effects of endorepellin on VEGF-directed endothelial cell migration is probably a direct consequence of cytoskeletal disassembly and not caused by dephosphorylation of key residues vital for migration on VEGFR2. This notion is further supported by functional studies showing that the accelerated angiogenic response following SHP-1 knockdown is largely dependent on increased proliferation.32

The results from the α2-chimera studies indicate that a unique motif in the cytoplasmic tail of integrin α2 is crucial for interaction with SHP-1, a concept strengthened by the fact that no tyrosine phosphorylation–mediated activity is attributed to the integrin β1 chain in endothelial cells grown on collagen.17 The closely related integrin α1 subunit activates the tyrosine phosphatase TCPTP when attached to collagen.30,41 A short and unique sequence at its C-terminus binds the N-terminal part of TCPTP, thereby relieving the phosphatase of its inactive conformation.30 Free SHP-1 is in a similar autoinhibited conformation, with its N-terminus SH-2 domain folded over the catalytic domain by a charge-dependent interaction.26,42 The C-terminal SH-2 domain is in this closed conformation exposed and could function as an antenna searching for motives that activate the phosphatase. Binding of the C-terminal SH-2 domain to a target distorts the closed conformation, which weakens the autoinhibitory connection.42 The precise nature of the interaction between integrin α2 and α3 with SHP-1 is not known. However, in analogy to the TCTPT interaction with integrin α1, SHP-1 could recognize a common motif in the integrin α2 and α3 cytoplasmic tails. Alignment of integrin α2 with integrin α3B, the integrin α3 isoform expressed in the vein endothelial cells used for the TIMP-2 studies, shows similarities in their nonconserved C-terminal sequences (supplemental Figure 8). Both contain an arginine 2 amino acid residue upstream of a tyrosine residue, a polar residue 1 amino acid downstream followed by a methionine. Interestingly, this sequence matches the consensus sequence for peptides that bind the SHP-1 C-terminal SH2 domain.43

Nuclear translocation of SHP-1 is cell-context dependent. In nonhematopoietic cells, SHP-1 shows more nuclear localization than hematopoietic cells.26 However, after TIMP-1 stimulation of germinal center B cells SHP-1 is translocated to the nucleus.25 This is in agreement with our finding showing that endorepellin stimulation leads to nuclear translocation of SHP-1 in the myogenic α2β1+ C2C12. Nuclear SHP-1 could dephosphorylate key transcription factors, such as STAT3,25,26 but the precise effect of nuclear SHP-1 remains to be clarified.

A novel result of our study was the decline of SHP-1 levels in liver, kidney, and spleen from α2β1-null animals, in addition to the pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells. Moreover, tyrosine phosphatase activity from SHP-1 immunoprecipitated from the liver of α2β1−/− mice was also significantly reduced. These results suggest that α2β1 is necessary to stabilize SHP-1, perhaps by prolonging its half-life. Both integrin α2β1−/−44 and the viable Shp-1−/− mice, known as moth-eaten mice,45 exhibit impairment of the immune system. The α2β1-null mice display reduced neutrophil recruitment on peritonitis induced by Listeria monocytogenes or the fungal polysaccharide zymosan.44 The defective response to Listeria was considered to be due to crosstalk between integrin α2β1 and Met, the receptor for hepatocyte growth factor and the Listeria pathogen internalin B.46 Zymosan is not a known ligand for Met, but interacts with the Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR-2),47 which in turn physically associates with SHP-1.48 Although SHP-1 has been mainly implicated as a negative modulator of cytokine signaling, it can also act as a positive factor for various cytokines, including TNF-α, interferon α, interleukin-4 (IL-4) and IL-1049 and TLR-3– and TLR-4–induced production of interferon β.50 Interestingly, integrin α2β1–deficient mice show no increase in the IL-6 release after zymosan stimulation, and Listeria-infected α2β1−/− mice experience additional impairment in IL-β and TNF-α excretion.44 In light of our findings, the malfunctioning immune response to fungi and bacteria in the integrin α2β1−/− mice could be explained in part by concurrent decrease in total SHP-1 levels and phosphatase activity.

Notably, the α2β1 null mice show an enhanced angiogenic response during wound healing7 and tumor xenograft development.4,46 This anomalous “hyperangiogenic phenotype” could also be attributed in part to a dual loss of a receptor for endorepellin and to a decline in SHP-1 levels and phosphatase activity. This is further supported by a study showing that siRNA-mediated knockdown of SHP-1 accelerates angiogenesis in a rat model of hind limb ischemia.31

In summary, we have shown that endorepellin activates the tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1 by the integrin α2β1 receptor. This finding substantially illuminates the mechanism of action of endorepellin in inducing endothelial cell silencing and is beneficial to further our understanding of angiogenesis in general and for the development of novel therapeutics for diseases in which controlled de novo blood vessel formation is of importance.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Angela McQuillan for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (grants RO1 CA39481, RO1 CA47282, RO1 CA120975) and by a grant from the Mizutani Foundation (R.V.I.).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: A.N. designed and performed research and wrote the manuscript; Z.P.S. performed research; D.G., T.K., B.E., and R.Z. provided cells and animals; A.P. performed research and provided cells; and R.V.I. was responsible for designing experiments, supervising the entire project, and writing the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Renato V. Iozzo, Department of Pathology, Anatomy, and Cell Biology, Thomas Jefferson University, 1020 Locust St, Ste 249 Jefferson Alumni Hall, Philadelphia, PA 19107; e-mail:iozzo@mail.jci.tju.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal