Abstract

Extranodal nasal-type natural killer (NK)/T-cell lymphoma is rarely observed in children and adolescents. We aim to investigate the clinical features, prognosis, and treatment outcomes in these patients. Thirty-seven patients were reviewed. There were 19, 14, 2, and 2 patients with stage I, stage II, stage III, and stage IV diseases, respectively. Among the patients with stage I and II disease, 19 patients received initial radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy, and 14 patients received chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy. The 4 patients with stage III and IV disease received primary chemotherapy and radiation of the primary tumor. Children and adolescents with extranodal nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma usually presented with early-stage disease, high frequency of B symptoms, good performance, low-risk age-adjusted international prognostic index, and chemoresistance. The complete response rate after initial radiotherapy was 73.7%, which was significantly higher than the response rate after initial chemotherapy (16.7%; P = .002). The 5-year overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) rates for all the patients were 77.0% and 68.5%, respectively. The corresponding OS and PFS rates for patients with stage I and II disease were 77.6% and 72.3%, respectively. Children and adolescents with early-stage extranodal nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma treated with primary radiotherapy had a favorable prognosis.

Introduction

Extranodal nasal-type natural killer (NK)/T-cell lymphoma, which was formerly known as angiocentric lymphoma, is a rare lymphoid malignancy in Western countries, but it is more prevalent in Asia and South America.1-6 In China, this condition accounts for 2% to 10% of all cases of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL).7-11 The distribution of the pathologic subtypes of lymphoma among children is remarkably different from that in adults.12-14 In children, the most common subtypes are aggressive lymphomas such as lymphoblastic lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, Burkitt lymphoma, anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, and peripheral T-cell lymphoma.12-14 However, extranodal nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma is extremely rare among children, although this condition is frequently diagnosed in male adults with the median age of approximately 45 years.7-11 Extranodal nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma shows an aggressive clinical course with distinct clinicopathologic characteristics.6,9-11 Furthermore, various studies have revealed the clinical diversity between patients with extranodal nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma of the nasal cavity, Waldeyer ring, and the extra-upper aerodigestive tract.15-20 However, the clinical behavior and outcomes in pediatric patients with extranodal nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma have not been defined. There are few cases reported in the literature.21-26 In the present study, we analyzed the disease-related factors in a large series of children and adolescents with extranodal nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma to better characterize the clinical features, prognosis, and outcomes of this uncommon childhood malignancy.

Methods

Study population

Between January 1988 and June 2008, 37 consecutive children and adolescents (age, 21 years or younger) who were newly diagnosed with extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma of the upper aerodigestive tract were enrolled in the Cancer Hospital of Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (CAMS) and Peking Union Medical College (PUMC). The diagnosis of extranodal nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma was based on the evaluation of the histopathologic and immunohistochemical results according to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification for lymphomas.27 All the patients showed the pathologic features of angiocentricity, zone necrosis, and polymorphism of individual cells. The immunohistochemical studies revealed that the tumor cells expressed NK/T-cell markers, including CD45RO, CD2, CD3ϵ, CD56, and/or cytotoxic molecules (T-cell intracellular antigen-1/granzyme B), but they did not express B-cell markers such as CD20 and/or CD79α. In situ hybridization for Epstein-Barr virus–encoded RNA was performed in 7 patients in the later part of this study, and 6 of them were Epstein-Barr virus positive. Patients with peripheral T-cell lymphoma were excluded from this study; some of the patients included in this study had also been included in our previous studies.10,19,20 The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the CAMS/PUMC and included patient informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Staging evaluation

The pretreatment clinical investigations included physical examination, serum biochemical assessments, determination of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels, computed tomography and/or magnetic resonance imaging of the head and neck, computed tomography of the thorax, abdomen, and pelvis, and examination of the bone marrow aspiration smears. The cases were staged according to the Ann Arbor staging system.

Because all the patients in this series were children and adolescents, we used the age-adjusted international prognostic index (aaIPI).28 The prognostic factors used in the aaIPI assessments included LDH levels, performance status, and Ann Arbor stage except age and extranodal involvement.

Treatment

The patients were treated according to the Ann Arbor stage. Radiotherapy was considered as the primary therapy for localized diseases. All the patients with stage I and II disease received radiotherapy alone or radiotherapy combined with chemotherapy. Among the 33 patients with stage I and II disease, 19 patients were treated with primary radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy, whereas 14 patients were treated with short course (usually 1-4 cycles) of combination chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy. The 4 patients with stage III and stage IV disease received primary chemotherapy along with irradiation of the primary tumor.

Radiotherapy was administered to all the 37 patients. Among these, 28 patients were irradiated using conventional techniques, whereas 9 recent cases were treated using intensity-modulated radiotherapy. The clinical target volume (CTV) and radiation dose for nasal and Waldeyer ring NK/T-cell lymphomas were determined using previously described approaches.5,19 The median radiation dose for the primary tumor was 50 Gy with a range of 15 to 61 Gy, at a dose per fraction of 1.8 to 2 Gy. The majority (n = 27) of patients received radiation doses of 50 to 56 Gy (n = 24) or more (60-61 Gy, 50 Gy with a boost of 10-11 Gy to residual lesions, n = 3), whereas 10 patients received less than 50 Gy. For the latter patients, 8 patients received radiation doses of 40 to 46 Gy, and 2 patients received low doses of 15 Gy and 25 Gy due to the distant disease progression or advanced-stage disease. Extended-field radiotherapy was applied in children as the same in adult patients. Briefly, for nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma patients with stage IE disease limited to the nasal cavity (limited stage IE), CTV included the nasal cavity, bilateral frontal ethmoid sinuses, and ipsilateral maxillary sinus. For patients with extensive diseases or limited stage IE diseases close to the choanae, CTV was extended to encompass involved paranasal tissues, nasopharynx, and other adjacent organs. Similarly, for patients with Waldeyer ring NK/T-cell lymphoma, CTV included the whole Waldeyer ring (nasopharynx, tonsil, base of tongue, and oropharynx) and disease extension. Prophylactic cervical node irradiation was not given to patients with stage IE nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma, whereas it was routinely used for patients with stage IE Waldeyer ring NK/T-cell lymphoma. Overall, 2 of 15 patients with stage IE nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma and all patients (n = 4) with stage IE Waldeyer ring NK/T-cell lymphoma received prophylactic cervical node irradiation. For the remaining 18 patients with stage II-IV nasal and Waldeyer ring NK/T-cell lymphoma, the radiation fields were extended to encompass involved cervical lymph nodes.

Twenty-eight patients received combination chemotherapy, and the most common chemotherapeutic regimen was the CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) regimen or CHOP-like regimens. The number of chemotherapy cycles ranged from 1 to 9 (median, 4 cycles).

Statistics

Based on the international response criteria for NHL,29 complete response (CR) was defined as complete disappearance of all detectable clinical and radiographic evidence of disease. Patient characteristics and response rates were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher exact test. The overall survival (OS) was measured from the beginning of treatment to the last follow-up or death from any cause. Progression-free survival (PFS) was measured from the beginning of treatment to disease progression, relapse, death from any cause, or the last follow-up. OS and PFS were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. The intergroup differences in survival curves were calculated using the log-rank test. The prognostic factors analyzed included age, sex, performance status, tumor location, cervical lymph node involvement, B symptoms, LDH levels, Ann Arbor stage, and aaIPI.

Results

Patient characteristics

The clinical characteristics of the 37 patients are listed in Table 1. There were 24 males and 13 females (male-to-female ratio, 1.85:1). The median age of the patients was 17 years (range, 7-21 years). The primary lesions were located in the nasal cavity in 22 cases and in the Waldeyer ring in 15 cases.

Clinical features of extranodal nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma in children and adolescents

| Characteristic . | Patients . | |

|---|---|---|

| No. . | % . | |

| Age, y | ||

| 7-14 | 8 | 21.6 |

| 15-18 | 21 | 56.8 |

| 19-21 | 8 | 21.6 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 24 | 64.9 |

| Female | 13 | 35.1 |

| Primary site | ||

| Nasal cavity | 22 | 59.5 |

| Nasopharynx | 11 | 29.7 |

| Tonsil | 4 | 10.8 |

| Ann Arbor sage | ||

| I | 19 | 51.4 |

| II | 14 | 37.8 |

| III | 2 | 5.4 |

| IV | 2 | 5.4 |

| B symptoms | 23 | 62.2 |

| Elevated LDH level | 16 | 51.6 |

| ECOG score | ||

| 0 | 9 | 24.3 |

| 1 | 23 | 62.2 |

| 2 | 5 | 13.5 |

| Age-adjusted IPI | ||

| 0 | 16 | 43.2 |

| 1 | 18 | 48.6 |

| 2 | 3 | 8.1 |

| Cervical lymph node involved | ||

| Yes | 17 | 45.9 |

| No | 20 | 54.1 |

| Characteristic . | Patients . | |

|---|---|---|

| No. . | % . | |

| Age, y | ||

| 7-14 | 8 | 21.6 |

| 15-18 | 21 | 56.8 |

| 19-21 | 8 | 21.6 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 24 | 64.9 |

| Female | 13 | 35.1 |

| Primary site | ||

| Nasal cavity | 22 | 59.5 |

| Nasopharynx | 11 | 29.7 |

| Tonsil | 4 | 10.8 |

| Ann Arbor sage | ||

| I | 19 | 51.4 |

| II | 14 | 37.8 |

| III | 2 | 5.4 |

| IV | 2 | 5.4 |

| B symptoms | 23 | 62.2 |

| Elevated LDH level | 16 | 51.6 |

| ECOG score | ||

| 0 | 9 | 24.3 |

| 1 | 23 | 62.2 |

| 2 | 5 | 13.5 |

| Age-adjusted IPI | ||

| 0 | 16 | 43.2 |

| 1 | 18 | 48.6 |

| 2 | 3 | 8.1 |

| Cervical lymph node involved | ||

| Yes | 17 | 45.9 |

| No | 20 | 54.1 |

LDH indicates lactate dehydrogenase levels; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; and IPI, International Prognostic Index.

The most frequent clinical symptoms on presentation were nasal obstruction, odynophagia, dysphagia, and cervical lymphadenopathy. B symptoms were observed in 23 patients (62.2%). Cervical lymph node involvement was observed in 17 patients (45.9%). The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance score was 0 to 1 in 32 patients (86.5%). The aaIPI score was 1 or lower in 34 (91.9%) patients.

According to the Ann Arbor staging system, 19 patients (51.4%) had stage IE disease, 14 patients (37.8%) had stage IIE disease, and 4 patients (10.8%) had stage III and IV disease. Among the 22 patients with nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma, 15 patients had stage IE disease and 7 patients had stage IIE disease. Among the 15 patients with Waldeyer ring NK/T-cell lymphoma, 4, 7, and 4 patients had stage IE, stage IIE, and stage III/IV disease, respectively. The majority (68.2%) of patients with nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma presented with stage IE disease, and in contrast, most of the patients (73.3%) with Waldeyer ring NK/T-cell lymphoma presented with regional nodal involvement with or without distant dissemination (P = .013). Only 4 patients (26.7%) had stage IE disease without any nodal or distant involvement.

Paranasal extension was observed in 13 (59.1%) of the 22 patients with nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma, whereas involvement of adjacent organs was observed in 10 (66.7%) of the 15 patients with Waldeyer ring NK/T-cell lymphoma (P = .454). For the patients with nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma, the organs or tissues that were most frequently involved by the primary tumor were the ethmoid sinus (n = 8), maxillary sinus (n = 8), nasopharynx (n = 4), oropharynx (n = 3), and nasal skin (n = 2).

Treatment outcomes

The response rates are described in Table 2. Among the 37 patients, overall response was achieved in 33 patients (89.2%); in this group, the CR rate was 86.5%, and the partial response (PR) rate was 2.7%. The stable disease (SD) rate was 0%, and the progressive disease (PD) rate was 10.8%.

Response rates of various treatments for extranodal nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma in children and adolescents

| . | Total no. . | CR, no. (%) . | PR, no. (%) . | SD, no. (%) . | PD, no. (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients, n = 37 | |||||

| Response after initial therapy | |||||

| RT | 19 | 14 (73.7) | 1 (5.3) | 1 (5.3) | 3 (15.8) |

| CT | 18 | 3 (16.7) | 10 (55.6) | 2 (11.1) | 3 (16.7) |

| Response after therapy | |||||

| RT alone | 9 | 9 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| RT + CT | 10 | 7 (70.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (30.0) |

| CT + RT ± CT | 18 | 16 (88.9) | 1 (5.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (5.5) |

| Total | 37 | 32 (86.5) | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0) | 4 (10.8) |

| Stages I and II, n = 33 | |||||

| Response after initial therapy | |||||

| RT | 19 | 14 (73.7) | 1 (5.3) | 1 (5.3) | 3 (15.8) |

| CT | 14 | 3 (21.4) | 6 (42.9) | 2 (14.3) | 3 (21.4) |

| Response after therapy | |||||

| RT alone | 9 | 9 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| RT + CT | 10 | 7 (70.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (30.0) |

| CT + RT ± CT | 14 | 13 (92.9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (7.1) |

| Total | 33 | 29 (87.9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (12.1) |

| . | Total no. . | CR, no. (%) . | PR, no. (%) . | SD, no. (%) . | PD, no. (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients, n = 37 | |||||

| Response after initial therapy | |||||

| RT | 19 | 14 (73.7) | 1 (5.3) | 1 (5.3) | 3 (15.8) |

| CT | 18 | 3 (16.7) | 10 (55.6) | 2 (11.1) | 3 (16.7) |

| Response after therapy | |||||

| RT alone | 9 | 9 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| RT + CT | 10 | 7 (70.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (30.0) |

| CT + RT ± CT | 18 | 16 (88.9) | 1 (5.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (5.5) |

| Total | 37 | 32 (86.5) | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0) | 4 (10.8) |

| Stages I and II, n = 33 | |||||

| Response after initial therapy | |||||

| RT | 19 | 14 (73.7) | 1 (5.3) | 1 (5.3) | 3 (15.8) |

| CT | 14 | 3 (21.4) | 6 (42.9) | 2 (14.3) | 3 (21.4) |

| Response after therapy | |||||

| RT alone | 9 | 9 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| RT + CT | 10 | 7 (70.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (30.0) |

| CT + RT ± CT | 14 | 13 (92.9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (7.1) |

| Total | 33 | 29 (87.9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (12.1) |

RT indicates radiotherapy; CT, chemotherapy; CR, complete remission; PR, partial remission; SD, stable disease; and PD, progressive disease.

The CR rate after initial radiotherapy (14/19, 73.7%) was much higher than that after initial chemotherapy (3/18, 16.7%; P = .001). In the subgroup of 33 patients with stage IE and IIE disease, the similar response rates to radiotherapy and chemotherapy were observed (Table 2). The CR rates for initial radiotherapy and initial chemotherapy were 73.7% and 21.4%, respectively (P = .009).

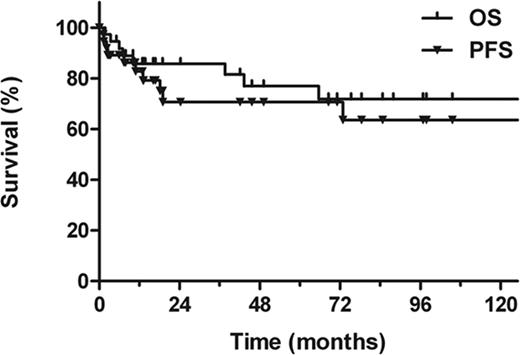

The 5-year OS and PFS rates for all the patients were 77.0% and 68.5%, respectively (median follow-up period, 42 months; Figure 1). The corresponding OS and PFS rates for patients with stage IE and IIE disease were 77.6% and 72.3%, respectively. Ten patients died of lymphoma (n = 8) or treatment-related complications (n = 2).

Overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) among all the pediatric patients with extranodal nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma.

Overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) among all the pediatric patients with extranodal nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma.

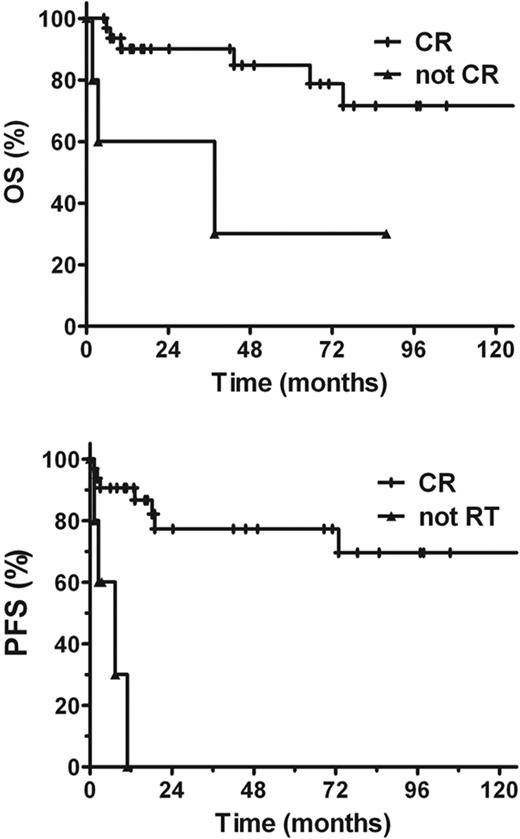

The prognosis of the patients with CR was significantly better than those without CR. The posttreatment 5-year OS rates of the patients with CR and those without CR were 84.8% and 30%, respectively (P = .006). The corresponding PFS rates were 77.3% and 0%, respectively (P = .000, Figure 2).

Overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) among the patients who achieved complete response (CR) and the patients who did not achieve CR.

Overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) among the patients who achieved complete response (CR) and the patients who did not achieve CR.

Prognostic factors

The patient characteristics were evaluated to determine their prognostic significance on OS and PFS (Table 3). The univariate analysis revealed that age, sex, B symptoms, performance status, cervical lymph node involvement, LDH levels, Ann Arbor stage, and aaIPI were not significant prognostic factors for OS and PFS. Patients with Waldeyer ring NK/T-cell lymphoma tended to have a better OS than those with nasal NK/T cell lymphoma. The 5-year OS and PFS rates for the patients with Waldeyer ring NK/T-cell lymphoma were 90.9% and 84.0%, respectively, and the corresponding values for the patients with nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma were 66.1% and 62.2%, respectively (P = .083 for OS, P = .160 for PFS).

Univariate analysis of the prognostic factors in children and adolescents with extranodal nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma

| . | 5-year OS . | 5-year PFS . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % . | P . | % . | P . | |

| Age, y | ||||

| 16 or younger | 72.7 | .463 | 65.7 | .955 |

| Older than 16 | 79.2 | 73.2 | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 80.6 | .58 | 64.9 | .877 |

| Female | 71.4 | 75.2 | ||

| ECOG score | ||||

| 0 or 1 | 72.6 | .146 | 66.5 | .495 |

| 2 or 3 | 100 | 80.0 | ||

| Primary site | ||||

| Nasal cavity | 66.1 | .083 | 62.2 | .160 |

| Waldeyer ring | 90.9 | 84.0 | ||

| Stage | ||||

| IE | 77.9 | .514 | 67.7 | .469 |

| IIE | 78.6 | 71.4 | ||

| B symptoms | ||||

| Yes | 80.2 | .758 | 66.1 | .877 |

| No | 75.3 | 70.3 | ||

| LDH | ||||

| Normal | 80.0 | .301 | 68.9 | .834 |

| High | 72.2 | 62.3 | ||

| Cervical lymph node involved | ||||

| Yes | 73.8 | .960 | 67.2 | .541 |

| No | 81.9 | 68.6 | ||

| Age-adjusted IPI | ||||

| 0 | 80.0 | .343 | 79.6 | .514 |

| 1 | 68.9 | 64.2 | ||

| CR after therapy | ||||

| CR | 84.8 | .006 | 77.3 | .000 |

| Not CR | 30.0 | 0 | ||

| . | 5-year OS . | 5-year PFS . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % . | P . | % . | P . | |

| Age, y | ||||

| 16 or younger | 72.7 | .463 | 65.7 | .955 |

| Older than 16 | 79.2 | 73.2 | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 80.6 | .58 | 64.9 | .877 |

| Female | 71.4 | 75.2 | ||

| ECOG score | ||||

| 0 or 1 | 72.6 | .146 | 66.5 | .495 |

| 2 or 3 | 100 | 80.0 | ||

| Primary site | ||||

| Nasal cavity | 66.1 | .083 | 62.2 | .160 |

| Waldeyer ring | 90.9 | 84.0 | ||

| Stage | ||||

| IE | 77.9 | .514 | 67.7 | .469 |

| IIE | 78.6 | 71.4 | ||

| B symptoms | ||||

| Yes | 80.2 | .758 | 66.1 | .877 |

| No | 75.3 | 70.3 | ||

| LDH | ||||

| Normal | 80.0 | .301 | 68.9 | .834 |

| High | 72.2 | 62.3 | ||

| Cervical lymph node involved | ||||

| Yes | 73.8 | .960 | 67.2 | .541 |

| No | 81.9 | 68.6 | ||

| Age-adjusted IPI | ||||

| 0 | 80.0 | .343 | 79.6 | .514 |

| 1 | 68.9 | 64.2 | ||

| CR after therapy | ||||

| CR | 84.8 | .006 | 77.3 | .000 |

| Not CR | 30.0 | 0 | ||

OS indicates overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; RT, radiotherapy; CT, chemotherapy; CR, complete remission; PR, partial remission; SD, stable disease; and PD, progression disease.

Patterns of treatment failure

Twelve patients showed disease progression (n = 4) during treatment or relapse (n = 8) after the treatment. Distant lymphatic or extranodal dissemination was observed in 9 patients, whereas local failure was observed in 3 patients. None of the patients showed lymph node recurrence in the head and neck area. The most frequent site of extranodal failure was the skin, followed by distant lymph nodes and bone marrow.

Late side-effect

With a median follow-up time of 42 months, neither severe long-term side effect nor second malignancy was observed in children and adolescents with extranodal nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma.

Discussion

Extranodal nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma is a well-recognized clinicopathologic entity among NHLs derived from activated NK cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes.27 This cohort of children and adolescents with extranodal nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma of the upper aerodigestive tract is the largest series analyzed to date, and the results of this study provide insight into the interesting clinical characteristics, prognosis, response to treatment, and outcomes. Similar to its expression characteristics in adults,2-6,10,19,20 extranodal nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma in children and adolescents is clinically characterized by male predominance, good performance, frequent extension to adjacent organs, large proportion of cases with stage I and II disease, frequent appearance of B symptoms and elevated LDH levels, low-risk aaIPI, propensity for extranodal spreading, and favorable prognosis.

Previous studies have shown that age is correlated with the prognosis in some cancers.14,28,30,31 Generally, the prognosis of childhood lymphomas is better than that of adult lymphomas.12,13 Because of the risk of radiation-related late complications, approximately 80% to 95% of pediatric lymphomas are currently cured by multiagent chemotherapy without radiotherapy.12-14 However, adult patients with extranodal nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma who received primary chemotherapy had a poor prognosis with a 5-year overall survival rate of only 10% to 49%, although the majority of these patients presented with localized-stage disease at diagnosis.4,6,8,9,18,32-34 In contrast, radiotherapy proved to be effective for treating patients with early-stage extranodal nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma.3,7,10,11,19,20,35,36 Seven large studies revealed that the clinical outcome of primary radiotherapy was superior to that achieved with initial chemotherapy or chemotherapy alone.7-9,18,32,34 The difference between the 5-year overall survival rates among patients treated with primary radiotherapy and primary chemotherapy was more than 30%.7-9,18,32,34 However, it was unclear whether the success achieved with primary radiotherapy translated into higher cure rates in children and adolescents with extranodal nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma. Consistent with the results of previous adult series,7-10,19,20 we observed a low CR rate (16.7%) among the patients treated with chemotherapy and a high CR rate (73.7%) among those treated with radiotherapy; these results signified resistance to chemotherapy and sensitivity to radiotherapy. Furthermore, we also showed that 5-year OS and PFS rates of 77.6% and 72.3% for stage I and II diseases, respectively, can be achieved with primary radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy. These results are similar to those reported in the previous studies on adults.3,10,19,20 In contrast, analyses of small series and published case reports on pediatric patients revealed that this disease presented with a fatal clinical course, disseminated disease, and chemoresistance.21-26

In this series, the CR rate after treatment was the lone significant prognostic factor in univariate analysis, whereas the other clinical parameters did not have any additional impact on the treatment outcome. This result can be attributed to the limited number of patients evaluated in the statistical analysis. The pediatric patients with Waldeyer ring NK/T-cell lymphoma tended to show better survival than those with nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma, which is consistent with the results of our previous study.20

We consider our results to be far from conclusion, and several important issues need to be addressed in pediatric patients. First, radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy was administered to all our patients, and a radical radiation dose of 50 Gy and extended field were used. The optimal radiation dose and the long-term side effects are critical issues in the pediatric patients who receive primary radiotherapy. Several prospective studies have revealed that advances in new radiotherapeutic techniques such as intensity-modulated radiotherapy, imaging-guided radiotherapy, and radiosurgery have reduced the side effects and improved the local control or survival.37-40 Thus, further studies should aim to validate the efficacy of primary radiotherapy with less toxicity in pediatric patients with NK/T-cell lymphoma. Second, because the majority of patients with extranodal nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma were resistant to CHOP-based chemotherapy, the optimal chemotherapeutic regimen for pediatric patients is uncertain and innovative systemic therapies are needed.

In conclusion, considering the lack of relevant information on pediatric nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma, our study provides valuable data on the clinical characteristics and the treatment outcomes of this typically adult tumor in pediatric patients. Early-stage patients who were treated with primary radiotherapy had a favorable prognosis. However, further studies are required to assess the treatment variables, study the biology of pediatric lymphomas, and clarify the differences between adult and pediatric nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphomas.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (30870736).

Authorship

Contribution: Z.-Y.W. analyzed the data and wrote the paper; Y.-X.L. designed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper; and W.-H.W., J.J., H.W., Y.-W.S., Q.-F.L., S.-L.W., Y.-P.L., S.-N.Q., H.F., X.-F.L., and Z.-H.Y. selected the cases and analyzed the clinical data.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Ye-Xiong Li, Department of Radiation Oncology, Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (CAMS) and Peking Union Medical College (PUMC), PO Box 2258, Beijing 100021, People's Republic of China; e-mail: yexiong@yahoo.com.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal