In this issue of Blood, 2 articles on HCL demonstrate that standard cladribine treatment is ineffective if the IG genes of the leukemic cells are in the UM version1,2 and the IG genes used belong to the VH4-34 family.2

Hairy cell leukemia (HCL) is an uncommon chronic lymphoid malignancy of B-cell type. This malignancy owes its name to the prominent irregular cytoplasmic projections of the malignant cell and has several unusual and still elusive biological and clinical features. A variant (vHCL) may present with morphologic features intermediate between hairy cells (HCs) and prolymphocytes.3 A HC is a highly activated B cell that appears to have undergone the sequence of reactions that in normal immune response occur upon stimulation by antigen, accessory cells, and cytokines. Several phenotypic features of HCs—including the distinctive pattern of microvilli and ruffles that characterize HC morphology—are explicable in this context.

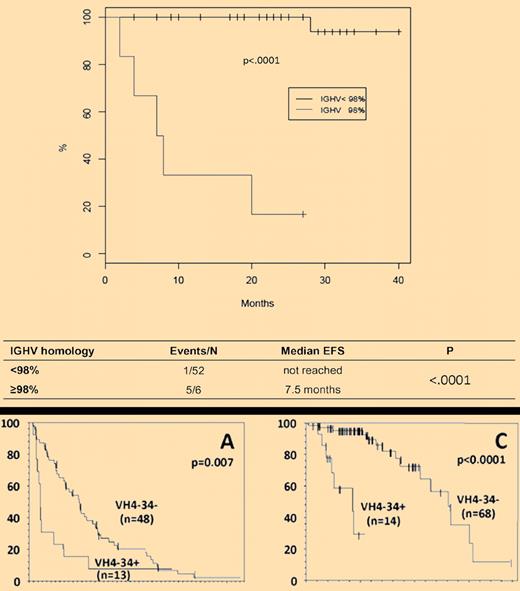

(Top) Event-free survival (EFS) of HCL patients treated with cladribine according to the presence (M) or the absence (UM) of IGHV somatic mutations. (Bottom) Progression-free survival (A) and overall survival (C) in patients with respect to the use of VH4-34 gene.

(Top) Event-free survival (EFS) of HCL patients treated with cladribine according to the presence (M) or the absence (UM) of IGHV somatic mutations. (Bottom) Progression-free survival (A) and overall survival (C) in patients with respect to the use of VH4-34 gene.

Many patients with HCL are asymptomatic and can be observed for months or years before requiring treatment, an exception being vHCL, which tends to present with high disease burden. Therapy of HCL is indicated when the patient develops one or more of the following conditions: significant cytopenias with related symptoms, symptomatic splenomegaly (or uncommonly adenopathy), constitutional symptoms. When treatment is warranted, the purine analogs cladribine and pentostatin have replaced splenectomy and interferon as the initial agents of choice.4,5 Because of ease of administration and paucity of toxicities, a single cycle of cladribine has become the preferred standard treatment. The majority of patients achieve a durable response. However, a proportion of patients, irrespective of whether they are classical or vHCL, either fail to respond or rather rapidly relapse.

Thus, we come to the relevance of the 2 papers discussed. The question is whether it is possible to recognize at diagnosis which patient will fail cladribine and therefore who could be spared a useless therapy and considered for an alternative type of treatment. Following in the footsteps of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL),6 where patients have a biased use of immunoglobulin heavy chain variable (IGHV) genes and the prognosis is significantly different according to the presence or the absence of IGHV somatic mutations, the 2 studies have investigated IG genes in 2 large series of patients. Forconi and colleagues have prospectively studied 53 cases included in a multicenter Italian clinical trial of newly diagnosed HCL.1 They prove that the presence of UM IGHV genes defines a minor subset of patients who are refractory to single-agent cladribine and have a more aggressive behavior (see top panel of the figure). In their series, 5 of 58 cases were cladribine failures and all 5 were UM (compared with only 1 of 53 beneficial response). Arons and colleagues have retrospectively studied 82 patients, most seeking trials for a relapsed/refractory disease and representing a poor prognosis population.2 They have found that a high proportion of cases (14/82) were characterized by the use of the VH4-34 gene, irrespective of whether they had a classic or vHCL (see bottom panel of the figure). All but one of the VH4-34+ cases were UM. VH4-34+ cases had strikingly significant lower response rate and progression-free survival after initial treatment with cladribine and experienced a shorter overall survival from diagnosis (see bottom panel of the figure). In the Italian series, 1 of 5 cladribine failure cases was VH4-34. Plausibly, the difference in the VH4-34 frequency in the 2 studies reflects the differences in the patient populations (newly diagnosed vs poor prognosis) and in the study modality (prospective vs retrospective). The Italian study1 reinforces the concept brought up by Arons et al.2

The take-home message is that the study of IG genes has to become an integral part of the diagnostic workup in HCL, irrespective of whether the patient has a classic or a vHCL. The reason is that if the IG genes are in the UM version and the IG genes used belong to the VH4-34 family, standard cladribine treatment may be ineffective. Accordingly, in these patients, new forms of treatment including monoclonal antibodies are warranted and deserve specific multicenter trials. Not surprisingly, the clinical behavior of UM-HCL parallels that of UM-CLL, but new interesting questions emerge. The road is now open for clinicians and biologists to understand why VH4-34 is such a risky gene in HCL,2 whether it has something to do with the autoimmune complications that may occur in HCL and also whether the rather high incidence of TP53 disfunction detected in the UM cases1 may provide a clue to understanding the mechanism of cladribine resistance in the UM-HCL group and more generally to purine analogs.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests. ■

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal