Abstract

In mice and humans, the immunologic effects of developmental exposure to noninherited maternal antigens (NIMAs) are quite variable. This heterogeneity likely reflects differences in the relative levels of NIMA-specific T regulatory (TR) versus T effector (TE) cells. We hypothesized that maintenance of NIMA-specific TR cells in the adult requires continuous exposure to maternal cells and antigens (eg, maternal microchimerism [MMc]). To test this idea, we used 2 sensitive quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) tests to detect MMc in different organs of NIMAd-exposed H2b mice. MMc was detected in 100% of neonates and a majority (61%) of adults; nursing by a NIMA+ mother was essential for preserving MMc into adulthood. MMc was most prevalent in heart, lungs, liver, and blood, but was rarely detected in unfractionated lymphoid tissues. However, MMc was detectable in isolated CD4+, CD11b+, and CD11c+ cell subsets of spleen, and in lineage-positive cells in heart. Suppression of delayed type hypersensitivity (DTH) and in vivo lymphoproliferation correlated with MMc levels, suggesting a link between TR and maternal cell engraftment. In the absence of neonatal exposure to NIMA via breastfeeding, MMc was lost, which was accompanied by sensitization to NIMA in some offspring, indicating a role of oral exposure in maintaining a favorable TR > TE balance.

Introduction

Immunosuppressive drugs administered to prolong graft survival increase the risk of systemic infections1 and may encourage tumor growth.2,3 Taking advantage of natural tolerance induced by noninherited maternal antigens (NIMAs) is one of the more promising but still relatively unexplored approaches for reducing the immunosuppressive burden in organ and stem cell transplant recipients. The clinical benefits of developmentally acquired tolerance to NIMA were first noted by Owen et al4 more than 50 years ago. Since then, tolerogenic effects of NIMA have been documented at both T- and B-cell levels in a variety of clinical settings.5-7

The basis of the NIMA benefit to allograft survival is not clear. One possible explanation is that many normal babies go on to accept, as adults, a tiny transplant of cells from their mothers acquired during ontogeny and thus are already predisposed to accept a larger NIMA+ organ transplant. Although fetal and maternal circulations are completely separated, fetal tissue is bathed with maternal blood in animals with a hemochorial placenta (eg, mouse and human),8,9 creating opportunities for bidrectional transfer of mature cells as well as hematopoetic and pluripotent progenitors.10-15 Moreover, rare maternal cells in liver can be acquired through ingestion of colostrum after birth.15 The low frequency of maternal cells present in adult offspring (< 0.1%) is called “microchimerism” (Mc), a term also applied to rare donor cells that emigrate from graft-to-host tissue after organ transplantation. It has been suggested that Mc, while providing a miniscule antigen “load” to the host, may nonetheless have major immunobiologic significance.20 Others have argued that the presence of rare foreign antigen-bearing cells in host tissues is either “ignored” by the host immune system or exert no additional impact on tolerance or immunity to self- or alloantigens expressed by solid tissues.21 However, recent experiments have shown that not only the quantity, but also the quality (multilineage vs unilineage) of chimerism is important determining full versus “split” tolerance.22,23 In addition, the discovery of the “semi-direct” pathway of alloantigen recognition, alloantigen acquisition by host dendritic cells, has provided an amplification mechanism whereby allogeneic cells sequestered in tissues may exert a strong antigenic impact on the host.24

Yet, if rare maternal cells and antigens are present in professional antigen-presenting cells (APCs), sensitization to NIMA and elimination of maternal cells might be expected to occur in all immunocompetent offspring. A recent study16 showed why this does not happen in the human fetus. Instead of eliciting a dominant T effector (TE) cell response, maternal alloantigens promoted T regulatory (TR) cell proliferation in the fetal lymph node (LN) by a TGF-β–dependent mechanism, sparing the maternal cells.16 However, this study left unresolved the issue of whether the fetal TR cells, once induced, are long-lived cells that persist in the adult, regardless of maternal microchimerism (MMc) level or distribution, or whether they are short-lived cells that require continuous tolerogenic antigen input to survive.16

To get at this question, we tested the relationship between MMc and NIMA-specific TR cells in individual offspring using the mouse F1 backcross breeding model (B6 × BDF1) originally described by Zhang and Miller.25 We and others have previously reported strong tolerogenic effects of NIMAd exposure on fully allogeneic heterotopic heart transplantation survival26 and graft-versus-host disease,27 effects mediated in part by NIMAd-specific CD4+ TR cells.28,29 Because antigen-specific TR cells are likely the key to NIMA-induced tolerance, we wished to test the hypothesis that their level in a given individual would depend upon the level and quality of persisting maternal cells. We show here the interdependence of MMc and NIMA-specific TR cells in adult mice. Furthermore, we show that despite a high level of MMc in multiple organs at birth, maintenance of maternal cell engraftment, and favorable TR > TE balance into adulthood was dependent on nursing of the neonate by the semiallogeneic mother.

Methods

Source of mice, breeding, and typing

C57 BL/6 (B6; H-2b/b), DBA/2 (H-2d/d), B6D2F1 (BDF1;H-2b/d), and B6C3F1 (H2b/k) were purchased from Harlan Sprague Dawley. B6-GFP+/− mice (C57BL/6-Tg (ACTB-EGFP)1Osb/J;H-2b/bGFP+/−) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. F1 backcross breeding was performed to obtain offspring developmentally exposed or nonexposed to NIMAs26 (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). All offspring were weaned after 21 days of birth and typed using anti-H2Kd antibody (BD Biosciences) and for green fluorescent protein (GFP) by flow cytometry using a FACS Caliber (BD Biosciences). Homozygous H2b/b offspring (negative for GFP and/or H2Kd) aged 6 to 8 weeks were used for all experiments. All experiments were performed in accordance with National Institutes of Health (NIH) and United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) guidelines, after approval from the University of Wisconsin Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

DNA extraction and qPCR analysis

Heart, lungs, liver, brain, blood, pooled LNs (inguinal, popliteal, axillary, brachial, and cervical), bone marrow, thymus, and spleen were collected and teased apart. DNA extraction and amplification were performed as described in supplemental Methods. H2Dd forward primer (CCTTCCCAGAGCCTCCTTCA), H2Dd reverse primer (AGAACTCAGACCCTGCCCTTTAA), and probe (6FAM-TCCACCAAGACTAACACAGTAATCATTGCTGTTCC-BHQ) were purchased from Biotechnology Center, University of Wisconsin–Madison. GFP forward primer (CCACATGAAGCAGCAGGACTT), GFP reverse primer (GGTGCGCTCCTGGACGTA), and GFP probe (6FAM-TTCAAGTCCGCCATGCCCGAA-BHQ), designed by The Jackson Laboratory, were used to detect GFP+ maternal cells in NIMAD NIMAGFP offspring by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). Target DNA (1 μg, equivalent to ∼ 106 cells) for all samples was quantified using the standard curve and expressed as estimated gene equivalents (GEq) per 105 offspring cells. All samples were run in triplicate, and the 3 GEq values for each organ were averaged to get a final GEq per 105 values. More details are available in supplemental Methods.

Adoptive transfer DTH and in vivo MLR assays

Spleen cells from NIMAd-exposed and NIPAd control mice were tested in adoptive transfer delayed type hypersensitivity (DTH; subcutaneously in B6 footpad) and in vivo mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR; intravenously in BDF1 host). Measurement of swelling, lymphoproliferation, and TGF-β expression on CD4+ T cells were performed as described previously.28

Flow cytometry

Live (propidium iodide–negative) cells dimly expressing maternal class I and II MHC antigens were quantified in the weaned F1 backcross offspring using PE-labeled anti-H2Kd antibody and FITC-labeled I-E–specific antibody (BD Biosciences) in thymus, spleen, LNs, bone marrow, and blood. B6 and BDF1 cells were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. In some experiments, cells were also stained for CD4, CD8, CD11b, and CD11c (BD Biosciences), cell surface TGF-β1, and Foxp3 (eBioscience). The data were analyzed using either CellQuest or FlowJo (TreeStar) software.

Cell sorting

Spleen and bone marrow cells stained with magnetic bead–conjugated antibodies against CD11c, CD11b, CD4, and CD8 (Miltenyi Biotec) were sorted according to the manufacturer's protocol. Single-cell suspensions of heart tissue were obtained using dispase II and collagenase (Roche) according to the manufacturer's directions. The cardiac cells were stained with magnetic bead–conjugated lineage cocktail antibodies (CD5, CD45R [B220], CD11b, Gr-1 [Ly-6G/C], 7-4, and Ter-119; Miltenyi Biotec).

Statistics

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 5 software (GraphPad Software). The nonparametric Mann-Whitney test was used to analyze data. Linear regression was used to find correlation coefficients and P values comparing different parameters.

Results

Breeding strategies used to explore MMc

We used 2 different breeding strategies to analyze the tissue distribution and phenotypes of maternal cells in NIMAd-exposed mice. The first was a standard (BDF1 × B6) backcross26 (supplemental Figure 1A) from which 50% of the offspring were H2b/d and 50% were H2b/b; the latter were developmentally exposed to maternal H2d (BDF1 mother, B6 father; NIMAd). Control breedings (B6 mother, BDF1 father; NIPAd control) would have a similar percentage of H2b/b and H2b/d mice, but no maternal sources of Mc. Second, we used a breeding strategy outlined in supplemental Figure 1B wherein mothers were heterozygous for both H-2d and GFP, resulting in 25% of offspring that were H2b/b and GFP−/− (NIMAd NIMAGFP), which have been exposed to H2b/d and GFP+/− maternal cells. The NIPA control offspring (NIPAd NIPAGFP) in the latter model were also H2b/b and GFP−/− homozygotes with no in utero or oral exposure to maternal H2d and/or GFP.

NIMAd-exposed mice have a widespread tissue distribution of Mc

To detect rare H2b/d (maternal) cells in NIMAd-exposed offspring, we developed a novel qPCR technique to amplify maternal H2Dd DNA (Figure 1A). In the second breeding model, we used another qPCR to detect rare GFP DNA (supplemental Figure 2). As shown, the titration of BDF1 or BDF1-GFP → B6 DNA yielded a linear standard curve sensitive to as little as 0.1 gene equivalents per 100 000 cells (10−6). Analysis of NIPAd control mice showed that the transfer of GFP+ or H2d+ cells from siblings or father, either directly or indirectly via mother, to H2 b/b offspring is relatively inefficient—82% (13 of 16) of NIPA controls had no detectable Mc in any of the organs tested (Figure 1B). Mc was detected exclusively in heart samples in 3 of 16 NIPA control mice, at the level of 1 Geq per 105 cells (Figure 1B-C). However, this observation was not reproduced in NIPAd NIPAGFP control mice using the GFP qPCR method (0 of 6; Figure 1C). In contrast, Mc was frequently detected in multiple organs of NIMA-exposed mice (Figure 1B) at levels ranging from 0.1 to 50.0 Geq per 105 cells (Figure 1C). Specifically, we found that 61% (25 of 41) of the NIMAd-exposed mice had detectable levels of Mc in at least 1 organ, with most having Mc in 2 or more organs (Figure 1B). When an average Mc level in 8 or 9 organs was calculated, Mc was significantly higher in NIMA versus NIPA offspring (1.318 ± 2.49 GEq/105 vs 0.042 ± 0.07 GEq/105; P = .001 for H2Dd; 0.327 ± 0.511 GEq/105 vs 0.0 ± 0.0 GEq/105; P = .04 for GFP). Thus, one may conclude that the majority of the Mc detected in the NIMA offspring was due to maternal, not sibling, sources. We will therefore refer to the presence of H2Dd and GFP DNA in NIMAd-exposed offspring as MMc.

Microchimerism in F1 backcross offspring. (A) The left panel shows a representative PCR curve showing standard and negative controls. The right panel shows H2Dd standard curve. Each data point is shown as mean ± range of values. qPCR was performed with BDF1 DNA diluted into B6 DNA in different concentrations. B6 DNA and blank (DNAase-free water) were used as negative controls. Primers and probe specific for maternal H2Dd were used to detect maternal DNA. A standard curve was made from 15 independent experiments. (B) Histogram showing variability in the levels of Mc in NIMAd-exposed versus control F1 backcross mice (standard breeding), plotted by percentage of offspring with indicated number of organs positive by H2Dd qPCR. (C) Top panel shows tissue distribution of Mc in different organs of NIMAd-exposed (n = 41 [*n = 12 for blood only]) and NIPAd (n = 16) control mice expressed as H2Dd gene equivalents (GEq) per 105 cells. The y-axis shows estimated GEq per 105 cells. Bottom panel shows GFP Mc in different organs of NIMAd NIMAGFP-exposed (n = 11) and NIPAd NIPAGFP control (n = 6) mice. (D) Summary of tissue distribution data in panel C expressed as a percentage of NIMA-exposed mice with detectable levels of Mc in each organ.

Microchimerism in F1 backcross offspring. (A) The left panel shows a representative PCR curve showing standard and negative controls. The right panel shows H2Dd standard curve. Each data point is shown as mean ± range of values. qPCR was performed with BDF1 DNA diluted into B6 DNA in different concentrations. B6 DNA and blank (DNAase-free water) were used as negative controls. Primers and probe specific for maternal H2Dd were used to detect maternal DNA. A standard curve was made from 15 independent experiments. (B) Histogram showing variability in the levels of Mc in NIMAd-exposed versus control F1 backcross mice (standard breeding), plotted by percentage of offspring with indicated number of organs positive by H2Dd qPCR. (C) Top panel shows tissue distribution of Mc in different organs of NIMAd-exposed (n = 41 [*n = 12 for blood only]) and NIPAd (n = 16) control mice expressed as H2Dd gene equivalents (GEq) per 105 cells. The y-axis shows estimated GEq per 105 cells. Bottom panel shows GFP Mc in different organs of NIMAd NIMAGFP-exposed (n = 11) and NIPAd NIPAGFP control (n = 6) mice. (D) Summary of tissue distribution data in panel C expressed as a percentage of NIMA-exposed mice with detectable levels of Mc in each organ.

The distribution of MMc in offspring was somewhat surprising. A total of 3 nonlymphoid organs (heart, liver, and lung) exhibited the highest levels (Figure 1C) and incidences (Figure 1D) of MMc, with heart showing the presence of MMc most frequently, followed by liver and lungs. Brain tissue was rarely MMc+. Among the lymphoid compartments, peripheral blood frequently (5 of 12; 43%) exhibited MMc. However, MMc was rarely detected in total DNA isolated from LNs, bone marrow, thymus, or spleen (Figure 1D). Widespread distribution of MMc, with a similar tissue bias, was confirmed using the GFP qPCR assay (supplemental Figure 2) in NIMAd NIMAGFP-exposed mice (Figure 1C-D).

Lymphoid tissues of NIMAd-exposed mice contain MMc in professional APC subsets

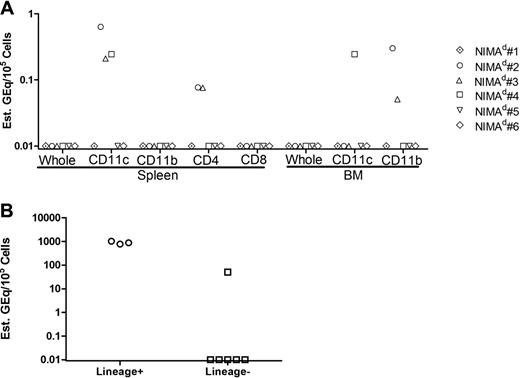

LN and spleen have recently been found to be key staging grounds for development of NIMA-specific TR cells in the human fetus and were also sites with significant MMc.16 We were therefore surprised to find that we could rarely detect MMc in unfractionated LN, bone marrow, spleen, and thymus cells (Figure 1D). To determine the incidence of MMc in isolated leukocyte subsets, we fractionated cells from spleen and bone marrow of NIMAd-exposed mice (supplemental Figure 3) and tested them for MMc. We found MMc in splenic CD11c+ dendritic cells (DCs), CD4+ (but not CD8+) lymphocytes, and CD11b+ bone marrow cell subsets (Figure 2A). These results demonstrate the greater sensitivity of subset analysis, revealing a 50% (3 of 6) MMc incidence compared with a 0 of 6 incidence of MMc in unsorted splenocytes and bone marrow cells. Importantly, these data suggest a type of MMc that includes professional class II+ APC.

MMc in hematopoetic versus parenchymal cell lineages. (A) Cells from spleen and bone marrow of 6 NIMAd-exposed mice (standard breeding) were separated by expression of CD4, CD8, CD11b, and CD11c using MACS beads, and DNA was extracted from separated populations and tested for H2Dd MMc. The figure shows levels of MMc (GEq/105 sorted cells) in the sorted cell populations. Individual mice are represented by symbols as shown. (B) Cells of hematopoietic lineages (lineage+) and nonhematopoietic lineages (lineage−) were sorted from single-cell suspensions of heart tissue pooled from 8 NIMAd-exposed mice. Lineage+ cells were sorted with a lineage cell depletion kit containing a cocktail of monoclonal antibodies against CD5, CD45R (B220), CD11b, Gr-1 (Ly-6G/C), 7-4, and Ter-119. Maternal cells were detected using H2Dd qPCR from the sorted fractions. The dots represent replicate values of analysis of the pooled lineage+ or lineage− cell DNA sample.

MMc in hematopoetic versus parenchymal cell lineages. (A) Cells from spleen and bone marrow of 6 NIMAd-exposed mice (standard breeding) were separated by expression of CD4, CD8, CD11b, and CD11c using MACS beads, and DNA was extracted from separated populations and tested for H2Dd MMc. The figure shows levels of MMc (GEq/105 sorted cells) in the sorted cell populations. Individual mice are represented by symbols as shown. (B) Cells of hematopoietic lineages (lineage+) and nonhematopoietic lineages (lineage−) were sorted from single-cell suspensions of heart tissue pooled from 8 NIMAd-exposed mice. Lineage+ cells were sorted with a lineage cell depletion kit containing a cocktail of monoclonal antibodies against CD5, CD45R (B220), CD11b, Gr-1 (Ly-6G/C), 7-4, and Ter-119. Maternal cells were detected using H2Dd qPCR from the sorted fractions. The dots represent replicate values of analysis of the pooled lineage+ or lineage− cell DNA sample.

Presence of maternal cells in hematopoietic lineages in the heart

The heart was the organ that exhibited the highest frequency of MMc (Figure 1D). To determine whether the MMc in heart was hematopoietic or parenchymal origin, we sorted cell populations obtained from 8 pooled heart tissues of NIMAd-exposed mice. We found a very strong H2Dd signal in DNA from hematopoietic lineage cells (lin+) in the heart compared with a 100-fold weaker signal in the nonhematopoietic cells (lin−), which would include cardiac myocytes, endothelium, and smooth muscle cells (Figure 2B).

Detection of GFP+ maternal cells by immunohistochemistry

Because heart and liver were most consistently MMc+, we investigated whether the maternal cells were detectable in these organs by immunohistochemistry. We detected GFP+ maternal cells in livers and hearts of NIMAd NIMAGFP-exposed offspring (supplemental Figure 4A-B), but not in NIPAd NIPAGFP control mice (supplemental Figure 4C-D) using an anti-GFP antibody. Consistent with the identification of lin+ cells in the heart as the predominant MMc type, the GFP+ cells were scattered within the heart tissue, as has been described for cardiac tissue macrophages.30 The thymus of a NIMAdNIMAGFP-exposed mouse, an organ consistently low or negative for MMc by qPCR (Figure 1), was found to contain rare GFP+ cells. The thymic GFP+ cells costained with anticytokeratin antibodies, indicating maternally derived thymic epithelial cells (supplemental Figure 4E).

NIMA-specific immune regulation

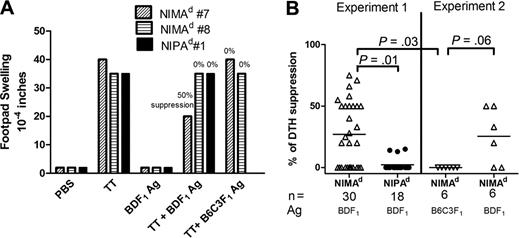

To detect NIMA-specific TR cells, we used DTH bystander suppression31-34 and “in vivo MLR” assays.28 In the first, we measured the ability of spleen cells from tetanus toxoid (TT)–immunized mice to mediate bystander suppression of a recall response to TT in the presence of noninherited H-2d (maternal) antigens. Figure 3A shows an example of a DTH assay in which splenocytes from 2 NIMAd-exposed mice and 1 NIPAd control mouse were tested. Splenocytes from all 3 responded strongly to TT, and weakly to BDF1 antigen. The response of NIMAd no. 7 induced by TT was suppressed by 50% in the presence of BDF1 (NIMA) antigen, indicating NIMA-specific TR in this mouse.28 In contrast, splenocytes from NIMAd no. 8 showed no evidence of bystander suppression, similar to the NIPAd control mouse. The variability in the degree of DTH bystander suppression in NIMAd-exposed mice (n = 36) is shown in Figure 3B. Approximately half of the NIMAd-exposed mice showed some degree of bystander suppression (20%-75%) in the presence of BDF1 antigen. In contrast, none of the NIPAd control mice had more than 20% bystander suppression (P = .001 vs NIMAd mice), confirming previously published data.28 Suppression seen in the NIMAd-exposed mice was NIMA-specific, as 4 of 6 NIMAd-exposed offspring showed some degree of bystander suppression in the presence of BDF1 antigen but not in the presence of third party B6C3F1 (H2b/k) antigen (Figure 3A-B).

Detection of NIMAd-specific TR cells using a DTH bystander suppression assay. Splenocytes were collected from NIMAd-exposed and NIPAd control offspring immunized with tetanus toxoid and diphtheria (TT/DT) vaccine 2 weeks previously. A total of 10 million splenocytes were injected into footpads of naive B6 recipients with coinjection inoculums: PBS, BDF1, or B6C3F1 Ag, or TT/DT. To measure bystander suppression, splenocytes were coinjected with BDF1Ag and TT/DT. Changes in footpad thickness were measured after 24 hours of injection to measure DTH reaction. (A) Examples of DTH bystander suppression assays. Spleen cells from 2 NIMAd-exposed mice (nos. 7 and 8) and 1 NIPAd control mouse (no. 1) that had been immunized with TT were coinjected into footpads with antigens shown on x-axis. Splenocytes from NIMAd no. 7 had a strong DTH response to TT but not to BDF1 antigen; the TT response was suppressed by 50% in the presence of BDF1 (maternal) Ag, but not in presence of third-party (B6C3F1) Ag. NIMAd no. 8 and the NIPAd control (no. 1) splenocytes did not suppress their strong anti-TT DTH responses in presence of the BDF1 Ag. (B) Summary of bystander suppression values in n = 54 mice. The horizontal lines represent mean values.

Detection of NIMAd-specific TR cells using a DTH bystander suppression assay. Splenocytes were collected from NIMAd-exposed and NIPAd control offspring immunized with tetanus toxoid and diphtheria (TT/DT) vaccine 2 weeks previously. A total of 10 million splenocytes were injected into footpads of naive B6 recipients with coinjection inoculums: PBS, BDF1, or B6C3F1 Ag, or TT/DT. To measure bystander suppression, splenocytes were coinjected with BDF1Ag and TT/DT. Changes in footpad thickness were measured after 24 hours of injection to measure DTH reaction. (A) Examples of DTH bystander suppression assays. Spleen cells from 2 NIMAd-exposed mice (nos. 7 and 8) and 1 NIPAd control mouse (no. 1) that had been immunized with TT were coinjected into footpads with antigens shown on x-axis. Splenocytes from NIMAd no. 7 had a strong DTH response to TT but not to BDF1 antigen; the TT response was suppressed by 50% in the presence of BDF1 (maternal) Ag, but not in presence of third-party (B6C3F1) Ag. NIMAd no. 8 and the NIPAd control (no. 1) splenocytes did not suppress their strong anti-TT DTH responses in presence of the BDF1 Ag. (B) Summary of bystander suppression values in n = 54 mice. The horizontal lines represent mean values.

Correlation between MMc distribution and NIMA-specific DTH suppression

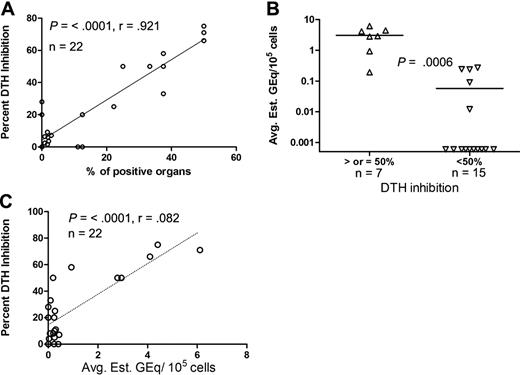

To determine if MMc was correlated with NIMA-specific DTH regulation, we compared the percentage of tissues containing MMc to the percentage of DTH suppression values in individual mice and found a strong linear correlation between these 2 variables (P = < .001, r = .92; Figure 4A). These data suggest that the widespread distribution of MMc is important for inducing or maintaining regulation to NIMA.

Correlation between the level of MMc and percentage of DTH inhibition. (A) Linear correlation between the percentage of DTH suppression and percentage of positive organs (out of a total of 8 or 9 organs tested per mouse) by qPCR. (B) NIMAd-exposed mice were divided into 2 groups on the basis of percentage of DTH suppression (50% and more and less than 50%) and plotted against the level (GEq/105 cells) of MMc. The y-axis shows average estimated GEq per 105 cells (average of 8 or 9 organs tested per mouse). (C) Percentage of DTH suppression plotted against levels of MMc averaged from 8 or 9 organs tested per mouse. The diagonal lines represent the best fit regression lines. Horizontal lines represent mean values.

Correlation between the level of MMc and percentage of DTH inhibition. (A) Linear correlation between the percentage of DTH suppression and percentage of positive organs (out of a total of 8 or 9 organs tested per mouse) by qPCR. (B) NIMAd-exposed mice were divided into 2 groups on the basis of percentage of DTH suppression (50% and more and less than 50%) and plotted against the level (GEq/105 cells) of MMc. The y-axis shows average estimated GEq per 105 cells (average of 8 or 9 organs tested per mouse). (C) Percentage of DTH suppression plotted against levels of MMc averaged from 8 or 9 organs tested per mouse. The diagonal lines represent the best fit regression lines. Horizontal lines represent mean values.

Another way to evaluate MMc is to take an average of the estimated Geq per 105 cells in all tissues tested, which takes into account both the calculated levels as well as the number of positive organs. It should be pointed out that a very high GEq per 105 cells value in 1 organ could skew the average, even if the distribution of MMc was very narrow. We compared this parameter with the extent of bystander suppression as both a discontinuous and a continuous variable. The average H2Dd Geq per 105 cells detected in a given mouse was strongly correlated with the presence of a greater than 50% bystander suppression response to maternal alloantigen (P < .001; Figure 4B), a threshold that we have previously found correlates with tolerance in human and mouse transplant recipients.33,34 There was also a significant correlation with the percentage of suppression of DTH as a continuous variable (P = < .001), although the linear relationship seen between DTH suppression and the number of MMc+ organs (r = .92; Figure 4A) was not as strong when the average Geq per 105 cells was used as the measure of MMc (r = 0.82; Figure 4C).

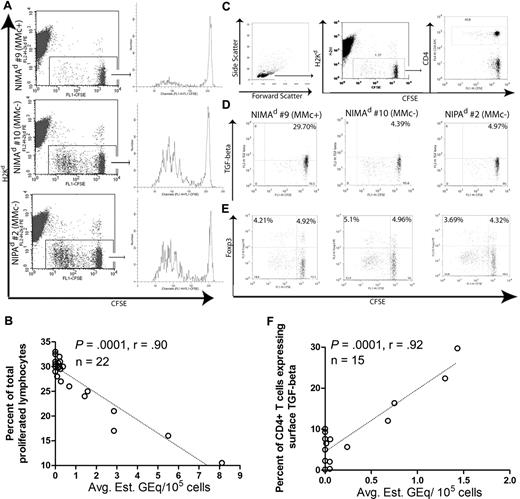

MMc is correlated with suppressed lymphoproliferation and NIMA-inducible TGF-β1+ CD4+ TR cells detected by in vivo MLR

Bystander suppression of a recall DTH reaction in presence of maternal antigens can be mediated by antigen-specific TR cells that produce IL-10 and express surface TGF-β/LAP complexes.28 Foxp3+ TR cells are also known to inhibit TE cell responses by both TGF-β–dependent and –independent mechanisms.35,36 We therefore investigated whether those offspring with high levels of MMc are more likely to exhibit decreased lymphoproliferative responses to maternal antigen, and to have CD4+ T cells with increased levels of Foxp3 or surface TGF-β in presence of maternal antigens. To this end, we performed in vivo MLR assays as described previously.28 Inguinal LN (ILN) and spleen cells were harvested from BDF1 mice, which had received CFSE-labeled splenocytes by intravenous injection 3 days earlier from either NIMAd-exposed or NIPAd control mice (H2b/b). Transferred (H2Kd-negative) lymphocytes present in the host ILNs were gated and analyzed for proliferation by CFSE dilution as shown in Figure 5A. Total lymphocytes derived from the MMcneg NIMAd-exposed mouse no. 10 and NIPAd control mouse no. 2 proliferated more vigorously in the semiallogeneic BDF1 host (maternal type) than that from MMc+ NIMAd-exposed mouse no. 9. When lymphoproliferation data from all NIMAd-exposed mice tested were compared with the average level of MMc, we found a strong inverse correlation in both BDF1 ILNs (P = < .001, r = −.90; n = 22; Figure 5B) and spleen (P = < .001, r = −.89; n = 22; data not shown).

“In vivo MLR” analysis of lymphocytes from NIMAd-exposed versus NIPAd control offspring. Splenocytes were harvested from NIMAd-exposed and NIPAd control mice and labeled with CFSE. CFSE-labeled splenocytes (50 × 106) were injected intravenously into a BDF1 recipient, which is the maternal type in the F1 backcross breeding system. After 3 days, splenocytes and ILN cells were harvested from the BDF1 recipients. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of lymphoproliferation in BDF1 hosts. H2Kd-negative CFSE-labeled splenic lymphocytes found in BDF1 ILNs were gated as shown. Total lymphocyte proliferation from MMc+ mouse NIMAd no. 9 was less than MMcneg NIMAd no. 10 and NIPA control (no. 2). (B) Inverse correlation between the level of MMc and percentage of proliferated responder lymphocytes recovered from BDF1 lymph nodes (n = 22). (C) Gating strategy for H2Kd-negative (donor) CD4+ T cells. (D) Surface TGF-β and (E) intracellular Foxp3 staining of donor CD4+ T cells. NIMAd no. 9–derived CD4+ T cells expressed a higher amount of surface TGF-β staining on nonproliferated CD4+ T cells than NIMAd no. 10 and NIPA control (no. 2). The horizontal line indicates the level of staining with isotype control antibody. (F) Correlation between the level of MMc and percentage of donor CD4+ T cells expressing surface TGF-β (n = 15). The diagonal lines represent the best fit regression lines in panels B and F.

“In vivo MLR” analysis of lymphocytes from NIMAd-exposed versus NIPAd control offspring. Splenocytes were harvested from NIMAd-exposed and NIPAd control mice and labeled with CFSE. CFSE-labeled splenocytes (50 × 106) were injected intravenously into a BDF1 recipient, which is the maternal type in the F1 backcross breeding system. After 3 days, splenocytes and ILN cells were harvested from the BDF1 recipients. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of lymphoproliferation in BDF1 hosts. H2Kd-negative CFSE-labeled splenic lymphocytes found in BDF1 ILNs were gated as shown. Total lymphocyte proliferation from MMc+ mouse NIMAd no. 9 was less than MMcneg NIMAd no. 10 and NIPA control (no. 2). (B) Inverse correlation between the level of MMc and percentage of proliferated responder lymphocytes recovered from BDF1 lymph nodes (n = 22). (C) Gating strategy for H2Kd-negative (donor) CD4+ T cells. (D) Surface TGF-β and (E) intracellular Foxp3 staining of donor CD4+ T cells. NIMAd no. 9–derived CD4+ T cells expressed a higher amount of surface TGF-β staining on nonproliferated CD4+ T cells than NIMAd no. 10 and NIPA control (no. 2). The horizontal line indicates the level of staining with isotype control antibody. (F) Correlation between the level of MMc and percentage of donor CD4+ T cells expressing surface TGF-β (n = 15). The diagonal lines represent the best fit regression lines in panels B and F.

To determine if we could identify TR cells among those recovered from the spleen or ILN after the 3-day in vivo MLR, CD4+ T cells were further analyzed for TGF-β and Foxp3 expressions. As shown in Figure 5C, we gated on the CD4+ T cells within the H2Kd-negative CFSE+ cells for determining surface TGF-β or nuclear Foxp3 expression on the donor CD4+ T cells. As shown in Figure 5D, NIMAd no. 9 (MMc+) had approximately 7-fold higher percentage of surface TGF-β+ cells within the CD4+ subset recovered from ILNs compared with MMc− NIMAd no. 10 or the NIPAd offspring. Strikingly, the TGF-β+ CD4+ TR cells were present almost exclusively in a CFSEbright, nonproliferating subpopulation. No significant difference was found in Foxp3 expression by transferred CD4+ T cells, either CFSEbright or CFSEdim (Figure 5E). When data from all NIMA mice tested were compared, there were significant correlations between the average level of MMc and the percentage of spleen-derived CD4+ TR cells expressing surface TGF-β in both ILNs (P = < .001, r = .92; n = 15; Figure 5F) and spleen (P = < .001, r = .88; n = 15; data not shown).

Evidence for cellular acquisition of maternal antigen in NIMAd-exposed mice

The strong correlation of CD4+ TR cells with MMc in adult offspring was impressive, but it did not explain how so few maternal cells could provide enough antigen for maintenance of tolerance to NIMA. One possibility is signal amplification via antigen acquisition or trogocytosis, a process of surface membrane exchange between cells that can be readily demonstrated both in vitro (supplemental Figure 5A) and in vivo.24 We found that H2Kd+ dimly stained cells (H2Kd-dim) were indeed detectable by flow cytometry in peripheral blood of NIMAd-exposed mice at levels above B6 “background” but were absent in NIPAd control mice (Figure 6A). The median channel fluorescence of H2Kd staining of the cells in NIMAd-exposed mice was intermediate between that of positive (BDF1) and negative (B6) parental strain controls. The H2Kd-dim cells might be maternal cells that have reduced their MHC class I expression. If this were so, then isolating the dimly positive cells should result in a high degree of enrichment for maternal DNA. To test this idea, we sorted H2Kd-dim splenocytes from 3 NIMA-exposed offspring and analyzed them for MMc. We found that H2Kd-dim cells from only 1 of 3 mice had detectable maternal DNA, and the level was low (∼ 1:50 000 cells). This suggests that a majority of the H2Kd-dim cells were offspring-derived and not maternal cells (supplemental Figure 5B). Interestingly, most of the offspring cells that expressed low levels of maternal H2Kd (MHC class I) also expressed IEd (MHC class II; supplemental Figure 5C). Together, these results suggest a process of antigen acquisition by migrating leukocytes of the offspring that encounter rare maternal cells, including professional APC in tissues. Double-staining with anti-H2Kd mAb plus CD4-, CD8-, CD11b-, or CD11c-specific antibodies revealed that primarily CD11b+ and CD11c+ APCs, and not T cells, expressed low levels of maternal antigen in vivo (supplemental Figure 6). Overall, we found an elevated percentage of H2-Kd-dim cells in all lymphoid tissues tested except thymus. The difference between NIMAd-exposed versus NIPAd control mice was highly significant in spleen (P < .001) and blood (P < .001; Figure 6B).

Cells of NIMAd-exposed mice express low levels of maternal MHC class I antigen. Cells from thymus, spleen, pooled LNs, bone marrow, and blood of NIMAd-exposed and NIPAd control mice were stained with anti-H2Kd antibody and analyzed by flow cytometry. A minimum of 106 events were collected for each sample. All cells in the live gate (propidium iodide–excluding) were included in the analysis. (A) An example of flow histograms of H2Kd expression on peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from a NIMAd-exposed, NIPAd control, B6 negative control, and BDF1 positive control mouse. (B) Summary data of percentage of H2Kd-dim cells in various lymphoid organs of NIMAd-exposed mice (▵) and NIPAd control mice (●). B6 background values have been subtracted. The horizontal line indicates the lower limit of sensitivity by flow cytometry. (C) Example of levels of maternal H2Kd-dim offspring cells in blood at 4 different time points after weaning. (D) Comparison of peak percentages of maternal antigen-dim offspring cells (from 4 different time points tested) among 3 groups of offspring. The error bars represent SEM.

Cells of NIMAd-exposed mice express low levels of maternal MHC class I antigen. Cells from thymus, spleen, pooled LNs, bone marrow, and blood of NIMAd-exposed and NIPAd control mice were stained with anti-H2Kd antibody and analyzed by flow cytometry. A minimum of 106 events were collected for each sample. All cells in the live gate (propidium iodide–excluding) were included in the analysis. (A) An example of flow histograms of H2Kd expression on peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from a NIMAd-exposed, NIPAd control, B6 negative control, and BDF1 positive control mouse. (B) Summary data of percentage of H2Kd-dim cells in various lymphoid organs of NIMAd-exposed mice (▵) and NIPAd control mice (●). B6 background values have been subtracted. The horizontal line indicates the lower limit of sensitivity by flow cytometry. (C) Example of levels of maternal H2Kd-dim offspring cells in blood at 4 different time points after weaning. (D) Comparison of peak percentages of maternal antigen-dim offspring cells (from 4 different time points tested) among 3 groups of offspring. The error bars represent SEM.

Given the strong correlation between the levels of NIMA-specific TR cells and MMc, and the fact that MMc has been reported to vary over time in mice and humans,37,38 we wished to determine whether the levels of MMc correlated with maternal H2Kd antigen expression. Blood was sampled from F1 backcross offspring weekly for 4 weeks after weaning, and all mice were killed 1 week later for MMc analysis. We found variability in the level of circulating maternal antigen-dim cells over time (Figure 6C). The 2 mice that expressed cell-surface maternal antigens, no. 11 and no. 12, were MMc+, while NIMA no. 13, negative for H2Kd antigen expression, was also MMcneg. Overall, MMc+ NIMAd-exposed mice had higher peak percentages of H2Kd-dim cells than MMcneg NIMAd-exposed and NIPAd control offspring (both P = .016; n = 13 mice tested; Figure 6D).

Sensitization and loss of MMc in the absence of oral exposure to NIMA via nursing

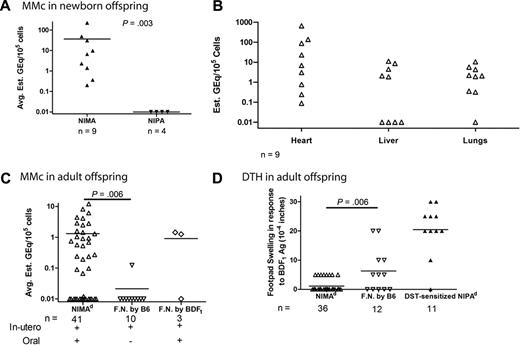

We have previously reported that when NIMAd-exposed mice were foster-nursed by B6 females, they failed to become tolerant to a DBA/2 heart allograft.26 We wished to determine whether (1) mice at birth have a high or low level of MMc, (2) the impact of foster-nursing by a B6 female on H-2d MMc, and (3) if depriving the offspring of oral NIMAd-exposure upsets the balance between NIMA-specific TR and TE cells, as measured by DTH analysis. When we measured MMc in newborn offspring (< 1 day old), we found 9 of 9 NIMAd-exposed offspring had MMc in at least 1 of 3 organs tested (Figure 7A). The level of MMc was variable in heart, liver and lungs, with the highest readings recorded in heart tissue. No H2Dd Mc was detected in the organs from 4 newborn NIPAd control offspring. The average level of MMc in heart, liver, and lungs of neonatal NIMAd-exposed offspring was approximately 14 times higher than that in the adult offspring (6-8 weeks old). A majority (61%; 25 of 41) of adult NIMAd mice nursed by their own mothers had detectable MMc in 1 or more organs (Figure 7B). However, when the NIMAd-exposed offspring were foster-nursed by B6 female mice, there was detectable MMc in only 1 of 10 adult mice (Figure 7B), and the 1 exception was a mouse that had MMc only in the heart (data not shown). As a control, some NIMAd-exposed offspring were foster-nursed by another BDF1 mother; 2 of 3 of these mice had a level of MMc similar to the average level found in naturally nursed NIMAd-exposed offspring (Figure 7B).

Oral exposure to maternal antigens is important in maintaining tolerance and preventing NIMA-induced sensitization. (A) Left panel shows average levels of MMc found in the heart, liver, and lungs in newborn offspring (less than 1 day old). Levels of MMc in heart, liver, and lungs of the newborn offspring are depicted in the right panel. (B) Newborn NIMAd-exposed mice were either nursed by the birth mother, or separated from their BDF1 mothers within 6 hours of birth and foster-nursed (F.N.) by B6 females. A control group of 3 NIMAd-exposed newborns were separated from their mothers and foster-nursed by another BDF1 female. Levels of H2Dd Mc (average of the organs tested) of the adult NIMAd-exposed mice (6-8 weeks old) nursed by their own mothers (NIMAd), or foster-nursed by B6 (F.N. by B6) or BDF1 mice (F.N. by BDF1) are shown. (C) Comparison of DTH responses to BDF1 antigens between NIMAd and NIMAd foster-nursed by B6. For a positive control response to BDF1 alloantigen, some NIPAd control mice were injected intravenously with BDF1 splenocytes 2 weeks before DTH assay and used as a source of sensitized splenocytes. The horizontal lines represent mean values of the observations.

Oral exposure to maternal antigens is important in maintaining tolerance and preventing NIMA-induced sensitization. (A) Left panel shows average levels of MMc found in the heart, liver, and lungs in newborn offspring (less than 1 day old). Levels of MMc in heart, liver, and lungs of the newborn offspring are depicted in the right panel. (B) Newborn NIMAd-exposed mice were either nursed by the birth mother, or separated from their BDF1 mothers within 6 hours of birth and foster-nursed (F.N.) by B6 females. A control group of 3 NIMAd-exposed newborns were separated from their mothers and foster-nursed by another BDF1 female. Levels of H2Dd Mc (average of the organs tested) of the adult NIMAd-exposed mice (6-8 weeks old) nursed by their own mothers (NIMAd), or foster-nursed by B6 (F.N. by B6) or BDF1 mice (F.N. by BDF1) are shown. (C) Comparison of DTH responses to BDF1 antigens between NIMAd and NIMAd foster-nursed by B6. For a positive control response to BDF1 alloantigen, some NIPAd control mice were injected intravenously with BDF1 splenocytes 2 weeks before DTH assay and used as a source of sensitized splenocytes. The horizontal lines represent mean values of the observations.

The loss of MMc in mice exposed in utero only to NIMAd antigens might be due to a passive process, or to active elimination of maternal cells by host TE cells now unopposed by TR cells. If the latter mechanism is correct, then there ought to be a shift away from regulation and toward sensitization in mice deprived of oral exposure to antigen. To determine the level of sensitization to maternal antigen, we used the DTH assay. We found that none of the naturally bred and nursed NIMAd mice (n = 36) responded to BDF1 antigen (0-5 × 10−4 inches net swelling), whereas 4 of 12 mice foster-nursed by a B6 mouse displayed a marginally elevated response (10-20 × 10−4 inches net swelling; Figure 7C). The mean footpad swelling was less than that observed in NIPAd controls that were sensitized as adults by BDF1 splenocytes before assay but significantly higher than that of standard bred and nursed NIMAd mice (P = .006). This finding suggests that, in the absence of oral exposure immediately after birth, in utero exposure to maternal antigens can result in NIMAd-specific sensitization, along with loss of MMc.

Discussion

Microchimerism has previously been shown to contribute to tolerance by induction of anergy or deletion of donor-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs).18,19 Although the presence of maternal thymic epithelial cells may indicate deletion of high-affinity maternal antigen-specific offspring T cells, the current study strongly supports a peripheral tolerance mechanism for the NIMA effect, a mechanism suggested by the recent discovery of coexisting MMc and NIMA-specific Foxp3+ TR cells in the human fetal LN.16 Given the well-recognized importance of TR cells in inducing and maintaining tolerance to allografts,39 the current study linking MMc to establishment of NIMA-specific TR cells, and the previous demonstrations of heart transplantation tolerance in approximately half of all NIMAd-exposed mice,26,28 the link between Mc and tolerance suggested previously26 has now gained additional support. However, when Mc is not the only source of alloantigen, as in the case where Mc is eliminated or reduced by antibody depletion but a transplanted organ remains,40 the importance of Mc in maintaining tolerance may be diminished. Moreover, not all forms of microchimerism were equally effective at inducing and maintaining TR cell–based tolerance. For example, isolated Mc in the heart, observed in some NIPA controls (Figure 1) and in 1 foster-nursed (by B6) NIMAd-exposed offspring (data not shown), may be instead a sign of split tolerance resulting from elimination of professional class II+ APCs.22,23

The immediate postnatal period appears to be critical for establishing a favorable TR > TE cell balance. When NIMAd-exposed mice were foster-nursed by B6 mothers, they lost not only their tolerance to a NIMA-expressing heart allograft,26 but also MMc (Figure 7). The loss of MMc was not due to the trauma of removal from the birth mother, because MMc was observed in 2 of 3 mice foster-nursed by a BDF1 female. This suggests a critical role of oral exposure to NIMA antigens in maintaining widespread MMc. When NIPAd control mice were nursed by BDF1 mothers, 2 of 6 offspring exhibited H2Dd Mc exclusively in the liver (P.D., unpublished observation, March 2009), consistent with a previous report.15 Aoyama et al,41 using the NIMAd breeding model, recently showed that nursing alone could induce limited protection against graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), whereas full protection required both in utero and oral exposure.

Because oral tolerance is known to generate TGF-β–producing TR cells,42,43 oral exposure to maternal MHC antigens present in breastmilk44 may generate additional NIMA-specific TR cells. The latter may be necessary to suppress NIMA-specific TE cells and thereby maintain MMc. Consistent with this interpretation, one-third (4 of 12) of the NIMAd-exposed mice foster-nursed by B6 mothers (in utero exposure only) responded to BDF1 antigen without any priming, while none (0 of 36) of the NIMAd-exposed offspring nursed by their own (BDF1) mothers did so. The poor outcome of maternal renal allografts in the precyclosporine era in recipients who had not been breastfed, compared with breastfed recipients,45 is consistent with sensitization in individuals lacking oral exposure to NIMA as infants.

TE cells, once they have expanded from naive precursors in response to antigen, often eliminate their antigen source; yet, because the memory TE express high levels of IL7 receptor, this compartment is still maintained in presence of IL7.46 In contrast, TR cells are generally IL7Rlow,47 and therefore may require antigen stimulation for their maintenance. The finding that CD11b+ and CD11c+ subsets of spleen and bone marrow contain rare maternal cells, the high MMc levels in hematopoeitic lin+ cells of the heart, and the evidence that professional APCs of offspring origin may acquire maternal MHC antigen, suggest that NIMA-specific TR cells could interact with a large number of APC-expressing NIMA antigens and allopeptides. TR-modified suppressive APCs48-50 of both host and maternal donor origin may well explain the phenomenon of MMc-linked CTL inhibition in a transplant recipient tolerant of a maternal kidney allograft.19 The finding of MMc in DCs and macrophage subsets is particularly important, because these rare maternal cells would express both NIMA class I and class II antigens, as well as the shared (inherited) class I and II antigens from the mother. This creates an additional avenue for tolerance: the induction of dual/allospecific CD4+ TR cells capable of interacting with both donor and host APCs. Such TR cells have recently been shown to be the extremely potent in inducing tolerance to allografts in mice,51 and may help explain the acceptance, after short-term immunosuppression, of renal allografts that are MHC class I–mismatched, but MHC class II–matched.52-54

In conclusion, we have found a striking correlation between MMc and NIMA-specific TR cells capable of suppressing both DTH and lymphoproliferative responses of TE cells in adult mice. The data suggest that maintenance of MMc is critically intertwined with NIMA-induced regulation and TR cell generation, which depends on oral exposure to maternal antigens via nursing, and may explain why some but not all offspring become microchimeric and tolerant to a maternal antigen-expressing allograft. Our data run counter to the idea proposed by Mold et al16 that the TR cells induced by fetal exposure to NIMA are long-lived memory cells that normally will persist into adulthood. If this were so, the level of persisting maternal antigen should not matter.

Although we have shown that MMc and NIMA-induced tolerance are correlated, we did not rule out the possibility that tolerance to NIMA can lead to persistence of maternal cells in the offspring. The issue of cause and effect of Mc21 can only be definitively resolved by targeted elimination of Mc in the adult mouse, to see if TR cells are rapidly lost or if their predominance over TE cells is maintained. Meanwhile, the precise role of microchimerism in acquired tolerance to solid organ or bone marrow transplants remains unresolved. Although trans vivo DTH and in vivo MLR assays are convincing surrogates for conventional allograft transplantations, correlating levels of MMc with subsequent survival of allografts is desirable. In light of our findings, and the recent identification of NIMA-minor H-specific CD8 TR cells in healthy individuals,55 pretransplantation screening to evaluate both Mc and TE/TR balance may now be warranted to determine whether a given individual is likely to accept allografts expressing NIMAs.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Steve Schumacher for technical assistance in typing mice, DNA extraction, and qPCR; M. Suresh, A. Shaaban, and A. Stevens for critical reading of the manuscript; and L. Haynes and E. Jankowska-Gan for their careful editing of the manuscript.

This work was supported by grant no. 5R01AI066219-04 from NIH (to W.J.B.).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: P.D. designed and performed all experiments (except DTH assay), analyzed data, and prepared the manuscript; M.M.-D. performed DTH assay and subset trogocytosis experiment (supplemental Figure 6), and edited the manuscript; J.L.B. tested primers; D.A.R. and J.R.T. helped with immunohistochemistry; Z.Y. designed primers; and W.J.B. helped in experiment design and manuscript editing.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: William J. Burlingham, H4/749 Clinical Science Center, 600 Highland Ave, Madison, WI 53792; e-mail: burlingham@surgery.wisc.edu.

![Figure 1. Microchimerism in F1 backcross offspring. (A) The left panel shows a representative PCR curve showing standard and negative controls. The right panel shows H2Dd standard curve. Each data point is shown as mean ± range of values. qPCR was performed with BDF1 DNA diluted into B6 DNA in different concentrations. B6 DNA and blank (DNAase-free water) were used as negative controls. Primers and probe specific for maternal H2Dd were used to detect maternal DNA. A standard curve was made from 15 independent experiments. (B) Histogram showing variability in the levels of Mc in NIMAd-exposed versus control F1 backcross mice (standard breeding), plotted by percentage of offspring with indicated number of organs positive by H2Dd qPCR. (C) Top panel shows tissue distribution of Mc in different organs of NIMAd-exposed (n = 41 [*n = 12 for blood only]) and NIPAd (n = 16) control mice expressed as H2Dd gene equivalents (GEq) per 105 cells. The y-axis shows estimated GEq per 105 cells. Bottom panel shows GFP Mc in different organs of NIMAd NIMAGFP-exposed (n = 11) and NIPAd NIPAGFP control (n = 6) mice. (D) Summary of tissue distribution data in panel C expressed as a percentage of NIMA-exposed mice with detectable levels of Mc in each organ.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/114/17/10.1182_blood-2009-03-213561/4/m_zh89990943260001.jpeg?Expires=1763605259&Signature=UH-u816RvNxR6gMABBatlgZRNRO1CDNIHDQ32bLq0Chp-Z3t~HbBskYTH70M4dk5Tn8Aa3iYf7ItVJMMm~KLmK6Oq-pExU3Rokc7KujtwncsdCM5p4RSnmIJwswAOYvYHkDb9xLdeP0II9yFKlkLK~1-AnHK5~PLt9PX6DYFzw7FOfZoGvRNu8FcSY2k53wu6NLwkxhtYgsqandKZNJ11GFCFMvU6tJ9LGo0v4FtFM3-uzVJpOW50Ab2CeOu0byDjWb3Q5Y5nSl~EcI5a7khDFib2XYxFeACrt17hMuvCAdG956f3QnOjenO9KniRPI8P~BX2R7gWVI-z4-rKevF3A__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal