Abstract

Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDSs) are clonal hematologic disorders that frequently represent an intermediate disease stage before progression to acute myeloid leukemia (AML). As such, study of MDS/AML can provide insight into the mechanisms of neoplastic evolution. In 184 patients with MDS and AML, DNA methylation microarray and high-density single nucleotide polymorphism array (SNP-A) karyotyping were used to assess the relative contributions of aberrant DNA methylation and chromosomal deletions to tumor-suppressor gene (TSG) silencing during disease progression. Aberrant methylation was seen in every sample, on average affecting 91 of 1505 CpG loci in early MDS and 179 of 1505 loci after blast transformation (refractory anemia with excess blasts [RAEB]/AML). In contrast, chromosome aberrations were seen in 79% of early MDS samples and 90% of RAEB/AML samples, and were not as widely distributed over the genome. Analysis of the most frequently aberrantly methylated genes identified FZD9 as a candidate TSG on chromosome 7. In patients with chromosome deletion at the FZD9 locus, aberrant methylation of the remaining allele was associated with the poorest clinical outcome. These results indicate that aberrant methylation can cooperate with chromosome deletions to silence TSG. However, the ubiquity, extent, and correlation with disease progression suggest that aberrant DNA methylation is the dominant mechanism for TSG silencing and clonal variation in MDS evolution to AML.

Introduction

Loss of heterozygosity (LOH) is an important event in neoplasia. For example, in the myeloid malignancies myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML), chromosome 7 deletions are among the most important predictors of outcome.1-3 The contribution of chromosomal deletions to the neoplastic process may involve loss of critical growth-regulating genes that would otherwise suppress the malignant phenotype. Such genes have been termed tumor suppressor genes (TSGs).4 Methylation of promoter CpG sites is an important factor regulating gene expression, including expression of TSGs.5-7 In cancer, aberrant DNA methylation in the promoters of TSGs is an alternative to chromosomal deletion for silencing TSGs.5-7 The clinical responses of MDS and AML to drugs that reverse aberrant hypermethylation, such as 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine and 5-azacytidine,8-11 suggest that aberrant hypermethylation plays a causative role in disease and is not just a side effect resulting from dysregulated proliferation or DNA damage. Finally, TSGs may be silenced by mutation (reviewed in Payne et al12 ). Therefore, aberrant DNA methylation, cytogenetic instability, and mutational instability are the triad of processes that can silence TSGs.

Evolutionary principles provide an important framework for understanding the process of neoplastic transformation. In essence, the 3 forms of genomic instability described here generate clonal variation, with subsequent selection by the microenvironment for the most favorable variants (reviewed in Breivik et al13 ). Since MDS frequently represents an intermediate stage before transformation to more aggressive disease (refractory anemia with excess blasts [RAEB] or AML) characterized by accumulation of myeloblasts, the study of MDS and AML can provide an insight into the relative contributions of aberrant methylation, chromosome instability, or mutational instability to the process of neoplastic evolution. With the advent of gene array technologies, it has become practical to karyotype malignant cells at high resolution using high-density single nucleotide polymorphism arrays (SNP-As) and, more recently, to simultaneously screen a large number of promoters for aberrant methylation. Genome-wide sequencing of individual tumors to assess the mutation spectrum in its entirety is still not widely practical. In any case, it has been estimated that instability at the chromosome level is more prevalent than mutational instability at the nucleotide level.14

In this study, we use gene array technologies to assess the extent of aberrant DNA methylation and chromosome aberrations in bone marrow samples from 184 patients with MDS or AML. Findings were correlated with clinical outcomes. In addition to the identification of previously unrecognized TSGs, by analyzing aberrant methylation and chromosome abnormalities at different stages of disease, the relative contribution of these processes to myeloid neoplastic evolution was revealed.

Methods

Patients and cell lines

Bone marrow aspirates (total N = 184) were collected from patients with MDS or AML seen between 2002 and 2007 and grouped according to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification system15 and International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS)16 classifications of MDS. Aspirates obtained from healthy individuals (N = 42; mean age, 43 years; range, 15-76 years) were used as normal bone marrow controls for the methylation array. CD34+ hematopoietic precursors used as controls were isolated from total bone marrow from 9 healthy donors.

A total of 6 human myeloid leukemia cell lines were studied, of which K-562 and TF1 are frequently described as erythroleukemia cell lines. Of the cell lines analyzed, KG1 and TF1 are CD34+ cell lines.

For SNP-A analysis, samples from 116 healthy control individuals were used. Informed consent for sample and data collection was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and conformed to protocols approved by the Cleveland Clinic institutional review board (IRB). In addition, a cohort of 61 Centre d'Etude du Polymorphisme Humain (CEPH; Utah residents with ancestry from northern and western Europe) HapMap individuals were used for comparison17 ; however, it should be noted that the criteria used to assign membership in the CEPH population have not been specified, except that all donors were residents of Utah.

Cytogenetic analysis

Cytogenetic analysis was performed on marrow aspirates according to standard methods. Chromosome preparations were G-banded using trypsin and Giemsa (GTG), and karyotypes were described according to the International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature (ISCN).18

DNA extraction

DNA was extracted using the ArchivePure DNA Blood Kit (5Prime, Gaithersburg, MD) from bone marrow aspirates. CD34+ cells were isolated from total bone marrow using immunomagnetic beads (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC).

Methylation array

Methylation detection was performed using Methylation Cancer Panel I and GoldenGate Assay kit with UDG from Illumina (San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol.19,20 Briefly, bisulfite conversion of DNA samples was performed using the EZ DNA methylation kit (Zymo Research, Orange, CA). For each CpG site, 2 pairs of probes were designed which corresponded to either the methylated or unmethylated state of the CpG site. Through allele-specific extension and ligation, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) templates are generated and then amplified by PCR using fluorescently labeled common primers. The resulting PCR products were hybridized to a bead array at sites bearing complementary address sequences. These hybridized targets contained a fluorescent label that denotes a methylated or unmethylated state for a given locus. Methylation status of the interrogated CpG site is then calculated as the ratio of fluorescent signal from one allele relative to the sum of both methylated and unmethylated alleles (β-value).

The β-value provides a continuous measure of levels of DNA methylation at a CpG site, ranging from 0 in the case of completely unmethylated sites to 1 in completely methylated sites.19 Frequently, we provide the β-value of all 1505 CpG sites analyzed in a particular sample as an overall average β-value. The overall average β-value may mask the fact that some CpG sites may demonstrate increased methylation compared with controls, whereas other CpG sites may demonstrate decreased methylation compared with controls. Therefore, methylation status of a CpG site was also dichotomized by comparing β-values between disease samples and controls: for each CpG site, a control methylation level was determined by analysis of 42 bone marrow samples from healthy individuals or normal CD34+ hematopoietic cells. β-values from disease samples were compared with this control value, and aberrant hypermethylation was defined as a β-value for a CpG site that was significantly greater (P < .001) than the average β-value of the same CpG site in the control group. The image extraction and statistical analysis were done with Beadstudio Methylation Module (Illumina). Several different control oligos were used to ensure the highest quality data, including allele-specific extension control, bisulfite conversion controls, extension gap controls, sex controls, first hybridization controls, second hybridization controls, negative controls, and contamination detection controls.

Methylation-specific PCR analysis

The methylated DNA was enriched with MethylCollector Kit (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. CpG-methylated DNA fragments prepared by MseI digestion specifically bind a His-tagged recombinant MBD2b protein. These protein-DNA complexes are captured with nickel-coated magnetic beads, and subsequent wash steps are performed with a stringent high-salt buffer to remove fragments with little or no methylation. The methylated DNA is then eluted from the beads in the presence of proteinase K. Primers used were as follows: DCC, 5′-TTGCCTGATCCAGCGTTTCCCT-3′, 5′-TCCTTGTCGTCGGTTGGGTAAAGT-3′; for DBC1, 5′-AGCTCTTGCTTCATTCTGGGAGGT-3′, 5′- TGTGTCGCGAG-ACCTGAGTGTTT-3′.

Expression analysis using semiquantitative RT-PCR

FZD9 expression was analyzed by semiquantitative RT-PCR. Total RNA was extracted from total bone marrow cells with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and cDNA was generated by first-strand cDNA synthesis using the superscript II RT kit (Invitrogen). Primers used were as follows: 5′-TGATGAGCTGACTGGGCTTTGCTA-3′ and 5′-TCCATGTTGAGGCGTTCGTAGACA-3′.

SNP-A analysis

The Gene Chip Mapping 250K Assay Kit (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) was used for SNP-A analysis and used per the manufacturer's instructions as previously described.21 When available, somatic changes not seen on metaphase cytogenetics were confirmed by rerunning sorted CD3+ lymphocytes. In addition, for confirmation, a number of samples (N = 107) were run on ultra-high-density Affymetrix 6.0 arrays and analyzed using Genotyping Console version 2.0 (Affymetrix). Signal intensity was analyzed and SNP calls were determined using Gene Chip Genotyping Analysis Software version 4.0 (GTYPE). Copy number (CN) and areas of uniparental disomy (UPD) were investigated using a hidden Markov model and CN analyzer for Affymetrix GeneChip Mapping 250K arrays (CNAG v3.0) as previously described.21,22 Lesions identified by SNP-A were compared with the Cancer Genome Anatomy Project database23 and our own internal control series (N = 116) to exclude known CN variants.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance of the difference between values of methylation level for different samples/groups was assessed using Beadstudio Methylation Module (Illumina). Spearman correlation was determined between methylation levels of replicate samples. Survival analyses were performed using the Kaplan-Meier product-limit method and the log-rank test.

Results

Principles and validation of global methylation array

An array-based DNA methylation profiling platform was applied to assess the methylation status of 1505 CpG sites selected from the 5′ regulatory regions of 807 genes.19 The genes on this array were chosen on the basis of their importance to cancer development and progression, including TSG and oncogenes.20 The β-value provides a continuous measure of levels of DNA methylation at a CpG site, ranging from 0 in the case of completely unmethylated sites to 1 in completely methylated sites.19 Methylation status of a CpG site was also dichotomized by comparing β-values between disease samples and controls: aberrant hypermethylation was defined as an average methylation level (β-value) for a CpG site that was significantly (P < .001) greater than the average methylation level of the same CpG site in the control cohort.

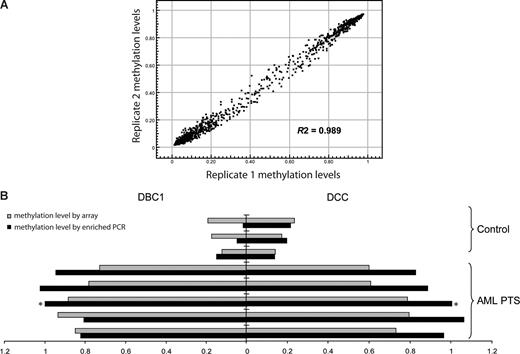

Methylation was analyzed in 6 leukemia cell lines, 184 patients with MDS or AML, 42 healthy control total bone marrow samples, and 9 healthy control CD34+ hematopoietic precursor samples (Table 1). The patients with MDS were divided into 3 groups for analysis: patients with disease that had transformed into a myeloblast-containing aggressive stage: a “RAEB/AML” group containing RAEB1, RAEB2, primary AML and secondary AML; a “low-risk MDS” group containing refractory anemia (RA), refractory cytopenia with multilineage dysplasia (RCMD), refractory anemia with ringed sideroblasts (RARS), refractory cytopenia with multilineage dysplasia and ringed sideroblasts (RCMD-RS), 5q− syndrome, myelodysplasia unclassifiable (MDS-U), MDS/myeloproliferative disorders unclassifiable (MPD-U), and refractory anemia with ringed sideroblasts associated with thrombocytosis (RARS-T); and a group with a specific myeloproliferative variant of MDS—chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML). To test the variation of the array, technical replicate samples were tested on 2 separate arrays. The average R2 was 0.989 (Figure 1A), indicating the high reproducibility of the analyses.

General characteristics of patients, N = 226

| Characteristics . | N . | Sex, M/F . | Age, average y ± SD . | Blast, % . | Mean IPSS . | Cytogenetics, normal/abnormal . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | 184 | |||||

| AML | 102 | |||||

| Primary AML | 56 | 23/33 | 54 ± 15 | 43.0 | 29/25 | |

| Secondary AML | 46 | 26/20 | 68 ± 11 | 43.0 | 11/29 | |

| MDS advanced | 28 | |||||

| RAEB1/2 | 28 | 18/10 | 63 ± 16 | 10.6 | 11/16 | |

| Low-risk MDS | 32 | |||||

| RA/RCMD | 19 | 11/8 | 65 ± 13 | 1.7 | 0.63* | 9/10 |

| RARS/RCMD-RS | 6 | 5/1 | 77 ± 3 | 1.3 | 0.21 | 5/1 |

| 5q syndrome | 3 | 0/3 | 55 ± 31 | 0.3 | 0.17 | 0/3 |

| MDS-U | 4 | 2/2 | 74 ± 8 | 2.0 | 0.75* | 1/2 |

| MDS/MPD | 22 | |||||

| MDS/MPD-U | 3 | 2/1 | 72 ± 6 | 5.0 | 0.83 | 1/2 |

| RARS-T | 5 | 3/2 | 73 ± 7 | 1.0 | 0 | 5/0 |

| CMML1/2 | 14 | 5/9 | 67 ± 10 | 18.3 | 11/3 | |

| Control | 42 | 20/22 | 43 ± 29 |

| Characteristics . | N . | Sex, M/F . | Age, average y ± SD . | Blast, % . | Mean IPSS . | Cytogenetics, normal/abnormal . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | 184 | |||||

| AML | 102 | |||||

| Primary AML | 56 | 23/33 | 54 ± 15 | 43.0 | 29/25 | |

| Secondary AML | 46 | 26/20 | 68 ± 11 | 43.0 | 11/29 | |

| MDS advanced | 28 | |||||

| RAEB1/2 | 28 | 18/10 | 63 ± 16 | 10.6 | 11/16 | |

| Low-risk MDS | 32 | |||||

| RA/RCMD | 19 | 11/8 | 65 ± 13 | 1.7 | 0.63* | 9/10 |

| RARS/RCMD-RS | 6 | 5/1 | 77 ± 3 | 1.3 | 0.21 | 5/1 |

| 5q syndrome | 3 | 0/3 | 55 ± 31 | 0.3 | 0.17 | 0/3 |

| MDS-U | 4 | 2/2 | 74 ± 8 | 2.0 | 0.75* | 1/2 |

| MDS/MPD | 22 | |||||

| MDS/MPD-U | 3 | 2/1 | 72 ± 6 | 5.0 | 0.83 | 1/2 |

| RARS-T | 5 | 3/2 | 73 ± 7 | 1.0 | 0 | 5/0 |

| CMML1/2 | 14 | 5/9 | 67 ± 10 | 18.3 | 11/3 | |

| Control | 42 | 20/22 | 43 ± 29 |

In some analyses, primary AML and secondary AML were analyzed together with RAEB1/2. MDS low risk was analyzed together with MDS/MPD-U and RARS-T.

RA indicates refractory anemia; RCMD, refractory cytopenia with multilineage dysplasia; RARS, refractory anemia with ringed sideroblasts; RCMD-RS, refractory cytopenia with multilineage dysplasia and ringed sideroblasts; MDS-U, myelodysplasia unclassifiable; MPD-U, myeloproliferative disorders unclassifiable; RARS-T, refractory anemia with ringed sideroblasts associated with marked thrombocytosis; and CMML, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia.

Contains patients who cannot be analyzed for IPSS.

Validation of the methylation array. (A) Methylation profiles of replicate samples show high reproducibility. Data shown are methylation β-values of 1505 CpG sites in which 1 and 0 represent high and low methylation levels, respectively. Each dot represents a CpG site. (B) Methylation array data correlate with methylation-enriched PCR results. Methylation-enriched PCR was used to measure the methylation status of CpG sites of DBC1 and DCC genes in bone marrow mononuclear cells from 3 healthy control donors and 5 patients with AML. ■ indicates the methylation-enriched PCR results represented as fold change compared with the results in the patient with AML marked with an asterisk.  indicates the array average methylation values (β-value) for the same CpG sites.

indicates the array average methylation values (β-value) for the same CpG sites.

Validation of the methylation array. (A) Methylation profiles of replicate samples show high reproducibility. Data shown are methylation β-values of 1505 CpG sites in which 1 and 0 represent high and low methylation levels, respectively. Each dot represents a CpG site. (B) Methylation array data correlate with methylation-enriched PCR results. Methylation-enriched PCR was used to measure the methylation status of CpG sites of DBC1 and DCC genes in bone marrow mononuclear cells from 3 healthy control donors and 5 patients with AML. ■ indicates the methylation-enriched PCR results represented as fold change compared with the results in the patient with AML marked with an asterisk.  indicates the array average methylation values (β-value) for the same CpG sites.

indicates the array average methylation values (β-value) for the same CpG sites.

To validate the results obtained through the methylation microarray, methylation-enriched PCR was used to detect the methylation level of exemplary genes (DBC1 and DCC). A strong correlation was observed between PCR results and array-based methylation analysis in the corresponding samples (Figure 1B).

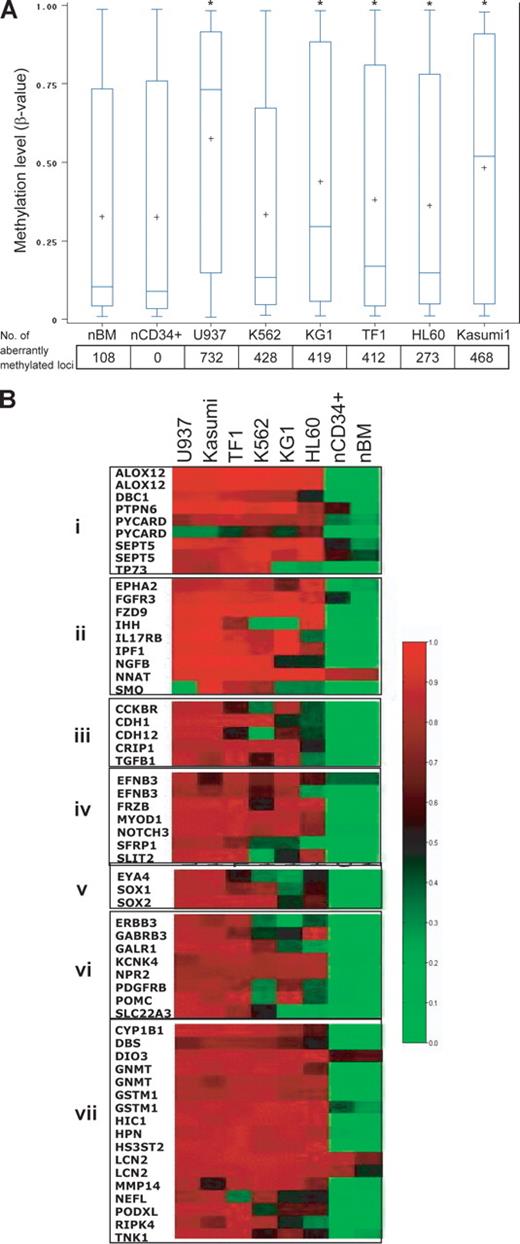

To provide a proof of principle, we performed methylation array analysis on 6 leukemia cell lines (K562, TF1, KG1, Kasumi, U937, and HL60). Average (and median) methylation levels in the cell lines were higher than levels in the normal CD34+ hematopoietic precursor cell controls. The number of aberrantly methylated loci was significantly higher in all 6 leukemia cell lines analyzed (Figure 2A), even when overall average methylation levels were not significantly increased (K562). This is because overall methylation levels can mask the fact that some CpG loci may be significantly hypermethylated, while others may be significantly hypomethylated. Each cell line showed a distinct methylation profile, and hierarchic clustering revealed that all malignant cell lines could be easily separated from both normal total bone marrow and CD34+ cells. K562 and TF1, frequently described as erythroleukemia cell lines, clustered as a markedly distinct group (data not shown). Of the 1505 CpG sites studied, 58 were aberrantly hypermethylated in all 6 leukemia cell lines (concordantly methylated) compared with controls (Figure 2B); these included genes involved in apoptosis, cycling, differentiation, proliferation, adhesion, chromosome architecture, and signal transduction (Figure 2B).

Hypermethylated genes in leukemic cell lines belong to many functional groups. (A) Myeloid leukemia cell lines have increased CpG site methylation levels (β-values), and a high frequency of aberrantly methylated CpG sites, compared with normal CD34+ hematopoietic cells. The vertical boxes delineate the interquartile range in β-values; T bars, 95% range of values. The horizontal line in the boxes indicates the median values and the plus sign indicates the mean. The asterisk indicates significant β-value difference with CD34+ cells in a Tukey Studentized Range t test. The numbers below the graph are the number of aberrantly methylated loci (compared with normal CD34+ control). The text explains why the frequency of aberrant methylation may be underestimated if only β-values are analyzed. (B) Heat-map analysis showing the methylation β-values of 58 CpG loci that were concordantly hypermethylated in all 6 leukemia cell lines. Red, black, and green correspond to high, medium, and low methylation levels, respectively. Genes were grouped according to their functions: group I, apoptosis and cell cycle; group II, cell development; group III, cell proliferation and adhesion; group IV, cell differentiation; group V, chromosome architecture; group VI, signal transduction; and group VII, other.

Hypermethylated genes in leukemic cell lines belong to many functional groups. (A) Myeloid leukemia cell lines have increased CpG site methylation levels (β-values), and a high frequency of aberrantly methylated CpG sites, compared with normal CD34+ hematopoietic cells. The vertical boxes delineate the interquartile range in β-values; T bars, 95% range of values. The horizontal line in the boxes indicates the median values and the plus sign indicates the mean. The asterisk indicates significant β-value difference with CD34+ cells in a Tukey Studentized Range t test. The numbers below the graph are the number of aberrantly methylated loci (compared with normal CD34+ control). The text explains why the frequency of aberrant methylation may be underestimated if only β-values are analyzed. (B) Heat-map analysis showing the methylation β-values of 58 CpG loci that were concordantly hypermethylated in all 6 leukemia cell lines. Red, black, and green correspond to high, medium, and low methylation levels, respectively. Genes were grouped according to their functions: group I, apoptosis and cell cycle; group II, cell development; group III, cell proliferation and adhesion; group IV, cell differentiation; group V, chromosome architecture; group VI, signal transduction; and group VII, other.

Promoter methylation correlates with disease evolution in patients with MDS/AML

We compared overall average methylation β-values and the number of aberrantly methylated CpG sites in patients with low-risk MDS versus those with MDS advanced to the blast stage (RAEB) or AML. Average methylation and the number of aberrantly methylated CpG sites were significantly greater in patients with RAEB/AML (average β-value 0.353; average number of aberrantly methylated CpG sites, 179 of 1505 in 138 of 807 genes) compared with patients with low-risk MDS (average β-value 0.331; average number of aberrantly methylated CpG sites, 91 of 1505 in 60 of 807 genes) or controls (average β-value 0.328; no aberrantly methylated genes; Figure 3A). The difference between low-risk MDS and controls was not statistically significant. Patients with CMML also displayed higher methylation levels (average β-value 0.336; average number of aberrantly methylated CpG sites, 125 of 1505 in 94 of 807 genes) than controls; however, the difference was not statistically significant (P = .076), possibly due to smaller sample size (N = 14).

Aberrant promoter methylation correlates with disease evolution. (A) Patients with RAEB/AML show a higher average and median methylation (β-value; P = .001) and a higher number of aberrantly methylated sites (P < .001) than those with low-risk MDS (aberrant methylation was defined as a methylation β-value for a CpG site that was significantly greater (P < .001) than the methylation β-value for the corresponding site in the group of normal bone marrow controls). The number of aberrantly methylated CpG sites in patients with complex cytogenetic abnormalities (defined as 3 or more abnormalities by standard metaphase karyotyping) is significantly higher (P = .05) than in patients without complex cytogenetic abnormalities; however, the average methylation level (β-value) was not significantly different (P = .23). Each dot represents the average array methylation level in a patient; the horizontal dashed line indicates the mean value for the patient group. Numbers below the graph represent the average number of aberrantly methylated CpG sites (of 1505 sites analyzed) in each patient group. Normal indicates normal whole bone marrow; CD34+ are normal CD34+ selected hematopoietic cells. (B) The number of concordantly hypermethylated sites by patient group, defined as CpG loci that were aberrantly methylated in more than 50% of patients with RAEB/AML, low-risk MDS, and CMML, respectively. Each circle represents a patient group, and the overlapping areas represent common aberrantly methylated genes. (C) CpG sites that became hypermethylated during evolution of RA to RCMD. Each dot represents a CpG site. The hypermethylated CpG sites are listed. (D,E) Concordantly hypermethylated loci in patients with low-risk MDS and RAEB/AML, respectively. Each dot represents a CpG site. Genes shown more than once represent those with more than one hypermethylated loci. The percentage refers to the proportion of patients with aberrant methylation at the specified locus.

Aberrant promoter methylation correlates with disease evolution. (A) Patients with RAEB/AML show a higher average and median methylation (β-value; P = .001) and a higher number of aberrantly methylated sites (P < .001) than those with low-risk MDS (aberrant methylation was defined as a methylation β-value for a CpG site that was significantly greater (P < .001) than the methylation β-value for the corresponding site in the group of normal bone marrow controls). The number of aberrantly methylated CpG sites in patients with complex cytogenetic abnormalities (defined as 3 or more abnormalities by standard metaphase karyotyping) is significantly higher (P = .05) than in patients without complex cytogenetic abnormalities; however, the average methylation level (β-value) was not significantly different (P = .23). Each dot represents the average array methylation level in a patient; the horizontal dashed line indicates the mean value for the patient group. Numbers below the graph represent the average number of aberrantly methylated CpG sites (of 1505 sites analyzed) in each patient group. Normal indicates normal whole bone marrow; CD34+ are normal CD34+ selected hematopoietic cells. (B) The number of concordantly hypermethylated sites by patient group, defined as CpG loci that were aberrantly methylated in more than 50% of patients with RAEB/AML, low-risk MDS, and CMML, respectively. Each circle represents a patient group, and the overlapping areas represent common aberrantly methylated genes. (C) CpG sites that became hypermethylated during evolution of RA to RCMD. Each dot represents a CpG site. The hypermethylated CpG sites are listed. (D,E) Concordantly hypermethylated loci in patients with low-risk MDS and RAEB/AML, respectively. Each dot represents a CpG site. Genes shown more than once represent those with more than one hypermethylated loci. The percentage refers to the proportion of patients with aberrant methylation at the specified locus.

We reasoned that genes aberrantly methylated in a large proportion of patients (concordantly methylated genes) may more likely represent pathologically consequential events. For each patient group, we defined concordantly hypermethylated sites as those that were hypermethylated in at least 50% of the patients within that group. Based on this criterion, patients with RAEB/AML had the most concordantly methylated CpG sites (51 sites), followed by CMML (39 CpG sites) and low-risk MDS (7 CpG sites). Among the concordantly hypermethylated sites in patients with RAEB/AML, 22 were also found to be concordantly hypermethylated in patients with CMML (Figure 3B). In RAEB/AML (advanced myeloid malignancies), the hypermethylated genes include tumor suppressor genes (DCC, HIC1) and genes involved in DNA repair (OGG1), cell-cycle control (DBC1), development and differentiation (EPHA5, HHIP, NTRK1, MYOD1, TDGF1, FGF2, HOXA5), and apoptosis (ALOX12; Figure 3B).

A total of 4 CpG sites (TSP50, NTRK1, 2 sites of GSTM1) were concordantly hypermethylated in both patients with low-risk MDS and RAEB/AML. In low-risk MDS, concordant methylation was also noted in 2 CpG sites of STK23, a gene that plays a role in differentiation and development and 1 CpG site of BRCA1, a TSG.

Methylation arrays can be applied to identify differences between morphologically defined groups and also serially in the same patient during disease progression. As an example of serial detection, we analyzed an MDS patient with RA who progressed to RCMD to characterize the evolution of the aberrant methylation profile (Figure 3C). A total of 25 of 1505 CpG sites became hypermethylated during disease progression. A high proportion of the genes affected were in the group of concordantly hypermethylated genes in RAEB/AML (Figure 3B,D).

Concordantly hypermethylated CpG sites were dispersed over 19 chromosomes (Figure 4B). Focal concentration of hypermethylation was also observed in some chromosomal segments. For example, chromosome region 17p13.1p13.3 contained hypermethylation in a CpG site of HIC1, 2 CpG sites of ALOX12, and a CpG site of TNK1.

Aberrant DNA hypermethylation was detected much more frequently than chromosome aberrations. (A) Proportion of patients with chromosome aberrations detected by standard metaphase karyotyping or SNP-A by patient group. (B) Idiogram representing the chromosomal localization of concordantly hypermethylated loci (loci hypermethylated in more than 50% of patients with low-risk MDS and RAEB/AML). Chromosomes are numbered at the top. Gene names are indicated beside each hypermethylated locus. Genes marked with a box are hypermethylated in both low-risk MDS and AML/RAEB. Genes shown more than once represent those with more than one hypermethylated locus. (C) On a chromosome by chromosome basis, the proportion of patients with aberrant methylation detected on that chromosome was higher than the proportion of patients with a chromosome aberration involving that chromosome.

Aberrant DNA hypermethylation was detected much more frequently than chromosome aberrations. (A) Proportion of patients with chromosome aberrations detected by standard metaphase karyotyping or SNP-A by patient group. (B) Idiogram representing the chromosomal localization of concordantly hypermethylated loci (loci hypermethylated in more than 50% of patients with low-risk MDS and RAEB/AML). Chromosomes are numbered at the top. Gene names are indicated beside each hypermethylated locus. Genes marked with a box are hypermethylated in both low-risk MDS and AML/RAEB. Genes shown more than once represent those with more than one hypermethylated locus. (C) On a chromosome by chromosome basis, the proportion of patients with aberrant methylation detected on that chromosome was higher than the proportion of patients with a chromosome aberration involving that chromosome.

Comparing frequency of chromosome aberrations with frequency of aberrant DNA methylation

A combined study using both methylation array and chromosome analysis was performed in 112 patients. We looked for chromosome abnormalities using standard metaphase and 250K SNP-A–based karyotyping (SNP-A can detect chromosome aberrations [including somatic uniparental disomy] at a high resolution, allowing for identification of cryptic chromosome lesions not noted on standard metaphase karyotyping24 ).

With routine metaphase cytogenetic analysis (standard karyotyping), 59 of 112 patients showed abnormal chromosomes and 53 of 112 had normal chromosomes. Of the 53 patients with normal chromosomes by standard karyotyping, 33 demonstrated chromosomal aberrations by SNP-A (ie, no abnormalities were found by both standard karyotyping and SNP-A in 20 patients). The proportion of patients with chromosomal aberrations detected by either standard karyotyping or by SNP-A increased from low-risk MDS (79%) to RAEB/AML (90%); however, this increase was not statistically significant (Figure 4A).

Aberrant methylation (of 182 CpG sites on average) was noted in all 20 patients with normal karyotype. In this group with normal cytogenetics by standard karyotyping and SNP-A, concordantly hypermethylated genes (defined as genes aberrantly methylated in more than 50% of patients) included ALOX12, FZD9, HIC1, HPN, and DBC1. When individual chromosomes were studied, the proportion of patients with aberrant methylation detected on the specific chromosomes was much higher than the proportion of patients with an identified chromosome lesion (Figure 4C). Therefore, aberrant methylation was seen in all patients and also appeared to be more widely distributed over the genome than chromosome aberrations.

The average number of aberrantly methylated CpG sites was higher in patients with complex cytogenetic abnormalities, but not to a statistically significant extent (Figure 3A). Similarly, the presence or absence of cytogenetic abnormalities did not correlate with the average DNA methylation score as measured by logistic regression.

Methylation at the FZD9 locus is an independent predictor of prognosis for patients with MDS/AML

The significant increase in aberrant CpG hypermethylation with progression of disease from low-risk MDS to RAEB/AML suggests that hypermethylation of specific genes could be predictive of clinical outcomes. We reasoned that the genes most frequently methylated in patients with advanced disease (RAEB/AML) may be most useful in this regard. Therefore, methylation of ALOX12, FZD9, GSTM1, HS3ST2, and HIC1 (genes that were concordantly methylated in more than 70% of patients with RAEB/AML) were correlated with overall survival.

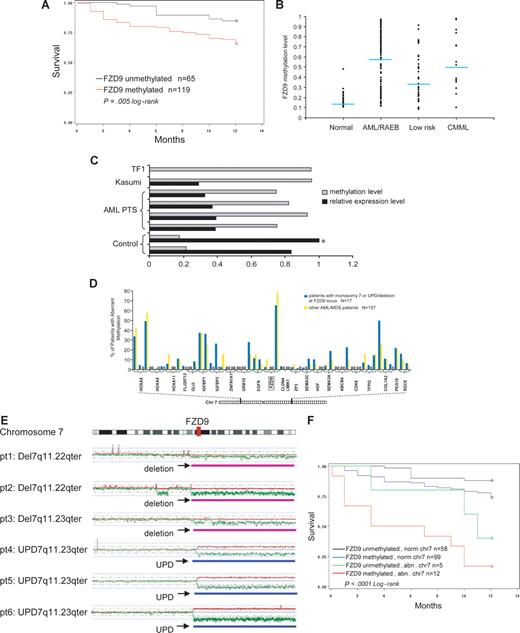

FZD9 is a receptor for Wnt in the Wnt pathway that is important in carcinogenesis.25 In these analyses, aberrant methylation of a CpG site −458 bp from the transcription start-site of FZD9 was significantly predictive of decreased survival at 12 months from diagnosis (Figure 5A; P = .005). The β-value of methylation at this site was also significantly predictive of survival in proportional hazards regression analysis (P = .002; data not shown). This CpG site was aberrantly methylated in 72% of patients with RAEB/AML, 48% of patients with low-risk MDS, and 2% of controls (Figure 5B). The hypermethylation of this CpG site inversely correlated with FZD9 transcript expression measured by semiquantitative RT-PCR (Figure 5C).

Aberrant methylation at the FZD9 locus is a predictor of prognosis in MDS/AML. (A) FZD9 hypermethylation is associated with decreased 12-month survival. (B) FZD9 methylation levels in individual patients classified by disease group. Each dot represents the methylation β-value of the FZD9 CpG site in an individual patient. The average methylation β-value of this CpG site for each patient group is indicated by the horizontal line. (C) FZD9 methylation is inversely correlated to FZD9 transcript expression.  represents the degree of FZD9 methylation in the sample; ■, the FZD9 expression levels determined by semiquantitative RT-PCR, defined as fold change compared with the control marked with an asterisk. (D) FZD9 CpG methylation is not part of a wider hypermethylation at its chromosome 7 locus. The height of the vertical bars represents the frequency of aberrant hypermethylation of the CpG sites designated along the horizontal line. The space between bars marked with 0 indicates analyzed CpG sites that were not hypermethylated in any patient. (E) Regions of chromosome deletion and UPD, detected by SNP-A, that involves the FZD9 locus. FZD9 is designated by the vertical red bar. Red lines depict single SNP signal intensity, whereas green lines present an average value of SNP signal intensity. The horizontal purple bar represents areas of chromosome deletion, whereas the horizontal blue bar represents areas of loss of heterozygosity through UPD. (F) Chromosomal deletion or duplication of an FZD9 allele, combined with aberrant methylation of the remaining allele, is associated with a worse prognosis than either abnormality alone.

represents the degree of FZD9 methylation in the sample; ■, the FZD9 expression levels determined by semiquantitative RT-PCR, defined as fold change compared with the control marked with an asterisk. (D) FZD9 CpG methylation is not part of a wider hypermethylation at its chromosome 7 locus. The height of the vertical bars represents the frequency of aberrant hypermethylation of the CpG sites designated along the horizontal line. The space between bars marked with 0 indicates analyzed CpG sites that were not hypermethylated in any patient. (E) Regions of chromosome deletion and UPD, detected by SNP-A, that involves the FZD9 locus. FZD9 is designated by the vertical red bar. Red lines depict single SNP signal intensity, whereas green lines present an average value of SNP signal intensity. The horizontal purple bar represents areas of chromosome deletion, whereas the horizontal blue bar represents areas of loss of heterozygosity through UPD. (F) Chromosomal deletion or duplication of an FZD9 allele, combined with aberrant methylation of the remaining allele, is associated with a worse prognosis than either abnormality alone.

Aberrant methylation at the FZD9 locus is a predictor of prognosis in MDS/AML. (A) FZD9 hypermethylation is associated with decreased 12-month survival. (B) FZD9 methylation levels in individual patients classified by disease group. Each dot represents the methylation β-value of the FZD9 CpG site in an individual patient. The average methylation β-value of this CpG site for each patient group is indicated by the horizontal line. (C) FZD9 methylation is inversely correlated to FZD9 transcript expression.  represents the degree of FZD9 methylation in the sample; ■, the FZD9 expression levels determined by semiquantitative RT-PCR, defined as fold change compared with the control marked with an asterisk. (D) FZD9 CpG methylation is not part of a wider hypermethylation at its chromosome 7 locus. The height of the vertical bars represents the frequency of aberrant hypermethylation of the CpG sites designated along the horizontal line. The space between bars marked with 0 indicates analyzed CpG sites that were not hypermethylated in any patient. (E) Regions of chromosome deletion and UPD, detected by SNP-A, that involves the FZD9 locus. FZD9 is designated by the vertical red bar. Red lines depict single SNP signal intensity, whereas green lines present an average value of SNP signal intensity. The horizontal purple bar represents areas of chromosome deletion, whereas the horizontal blue bar represents areas of loss of heterozygosity through UPD. (F) Chromosomal deletion or duplication of an FZD9 allele, combined with aberrant methylation of the remaining allele, is associated with a worse prognosis than either abnormality alone.

represents the degree of FZD9 methylation in the sample; ■, the FZD9 expression levels determined by semiquantitative RT-PCR, defined as fold change compared with the control marked with an asterisk. (D) FZD9 CpG methylation is not part of a wider hypermethylation at its chromosome 7 locus. The height of the vertical bars represents the frequency of aberrant hypermethylation of the CpG sites designated along the horizontal line. The space between bars marked with 0 indicates analyzed CpG sites that were not hypermethylated in any patient. (E) Regions of chromosome deletion and UPD, detected by SNP-A, that involves the FZD9 locus. FZD9 is designated by the vertical red bar. Red lines depict single SNP signal intensity, whereas green lines present an average value of SNP signal intensity. The horizontal purple bar represents areas of chromosome deletion, whereas the horizontal blue bar represents areas of loss of heterozygosity through UPD. (F) Chromosomal deletion or duplication of an FZD9 allele, combined with aberrant methylation of the remaining allele, is associated with a worse prognosis than either abnormality alone.

Of 3 CpG sites at the FZD9 promoter locus, only 1 was concordantly methylated. Furthermore, 50 CpG sites from 23 genes surrounding the methylated FZD9 site on chromosome 7 were not extensively hypermethylated (Figure 5D). Therefore, hypermethylation of the FZD9 CpG site does not appear to be a component of a more widespread or propagated hypermethylation.

Aberrant methylation and chromosomal abnormalities may cooperate to completely silence a TSG (functional knockout). Similarly, duplication of a methylated allele through UPD could potentially lead to complete TSG silencing. Therefore, we assessed the frequency of FZD9 methylation in patients with deletion or duplication of one allele through chromosomal abnormalities detected on standard metaphase karyotyping or SNP-A. A total of 17 patients had chromosome 7 lesions that affected the FZD9 locus (11 with monosomy 7, 3 with del7/7q lesions, and 3 with UPD7q; Figure 5E illustrates lesions detected by SNP-A). Aberrant methylation was noted in 12 (71%) of 17 of patients with chromosome abnormalities at the FZD9 locus compared with 99 (63%) of 157 of patients without chromosome abnormalities at the FZD9 locus; this difference was not statistically significant (P = .54, chi-test; Figure 5D; Table 2). Clinical outcome was poorest in patients with the combination of chromosome deletion of one FZD9 locus and aberrant methylation of the remaining FZD9 locus (Figure 5F). In multivariate analysis, chromosome 7 abnormalities and blasts of 5% or greater were independent predictors of prognosis, and aberrant FZD9 methylation approached statistical significance (Table 2). Complex cytogenetic abnormalities were associated with prognosis in univariate analysis, but this significance was lost in multivariate analyses that included FZD9 methylation, blasts of 5% or greater, and chromosome 7 abnormalities (Table 2).

FZD9 methylation is an independent predictor of prognosis in MDS/AML

| . | FZD9 methylation is associated with ≥ 5% blasts; P = .005 . | FZD9 methylation is not associated with chromosome 7 abnormalities; P = .54 . | FZD9 methylation is not associated with complex chr abnormalities; P = .84 . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blasts < 5%, n = 58 . | Blasts ≥ 5%, n = 126 . | Normal chr7, n = 157 . | Abnormal chr7, n = 17 . | < 3 chr abnorm., n = 131 . | ≥ 3 chr abnorm., n = 43 . | |

| FZD9 unmethylated | 50% (29/58) | 29% (36/126) | 37% (58/157) | 29% (5/17) | 37% (48/131) | 35% (15/43) |

| FZD9 methylated | 50% (29/58) | 71% (90/126) | 63% (99/157) | 71% (12/17) | 63% (83/131) | 65% (28/43) |

| . | FZD9 methylation is associated with ≥ 5% blasts; P = .005 . | FZD9 methylation is not associated with chromosome 7 abnormalities; P = .54 . | FZD9 methylation is not associated with complex chr abnormalities; P = .84 . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blasts < 5%, n = 58 . | Blasts ≥ 5%, n = 126 . | Normal chr7, n = 157 . | Abnormal chr7, n = 17 . | < 3 chr abnorm., n = 131 . | ≥ 3 chr abnorm., n = 43 . | |

| FZD9 unmethylated | 50% (29/58) | 29% (36/126) | 37% (58/157) | 29% (5/17) | 37% (48/131) | 35% (15/43) |

| FZD9 methylated | 50% (29/58) | 71% (90/126) | 63% (99/157) | 71% (12/17) | 63% (83/131) | 65% (28/43) |

| Chr 7 abnormalities and ≥ 5% blast are independent predictors of 12-mo survival by multivariate analysis. FZD9 methylation approaches significance. . | |

|---|---|

| Cox proportional hazards regression analysis . | P . |

| Blasts ≥5% | .019 |

| Chromosome 7 abnormality | <.001 |

| Complex chr abnormality | .17 |

| FZD9 methylation | .064 |

| Chr 7 abnormalities and ≥ 5% blast are independent predictors of 12-mo survival by multivariate analysis. FZD9 methylation approaches significance. . | |

|---|---|

| Cox proportional hazards regression analysis . | P . |

| Blasts ≥5% | .019 |

| Chromosome 7 abnormality | <.001 |

| Complex chr abnormality | .17 |

| FZD9 methylation | .064 |

The variables used in multivariate analysis were FZD9 methylation status, presence of chromosome 7 abnormalities, presence of complex chr abnormalities (≥ 3 abnormalities on cytogenetic analysis), and blasts ≥ 5%.

Chr indicates chromosome; and blasts %, bone marrow myeloblast percent.

The mechanisms that drive aberrant DNA methylation are not known. One possibility is that aberrant DNA methylation could in some way be triggered by chromosome instability. Although aberrant methylation of FZD9 was more prevalent in patients with blasts of 5% or greater, it was not associated with complex cytogenetic abnormalities (Table 2).

Discussion

Although aberrant methylation of specific genes has been noted in MDS and AML,26-28 identifying p15, E-cadherin, ER, MYOD1, and HIC111,26,29-32 as examples of TSG silenced by hypermethylation, most earlier studies were limited to analysis of a few specific loci.11,33,34 Therefore, the true extent of promoter methylation in hematologic malignancy remains largely unknown.26,27,35,36 The data presented here represent the first systematic study of bone marrow from a large cohort of patients with MDS and AML with a methylation array. Furthermore, the concurrent application of high-density SNP-A allowed a comparison of aberrant methylation with chromosome abnormalities in the same individual cases.

The Golden Gate chip hybridization technology used by Illumina methylation arrays constitutes a robust analytic methylation platform and produces reliable and highly reproducible data.20 Technical replicates in 2 individual assay plates generated comparable results. Fidelity of the array was also confirmed using methylation-specific PCR for randomly selected genes. Finally, methylation status of FZD9, a gene selected for more in-depth analysis, showed that FZD9-associated CpG site methylation correlated with decreased FZD9 transcript levels. The high-density SNP-A has been validated in our previous work, in which we confirmed the clinical significance and acquired somatic nature of chromosome abnormalities detected by SNP-A in patients with normal cytogenetics by standard karyotyping.24

Using methylation arrays, we show abnormal promoter methylation in more than one-sixth of the genes analyzed in CD34+ and CD34− AML cell lines as well as primary RAEB or AML cells as compared with control CD34+ cells. The methylated genes have designated roles in multiple cellular functions, including DNA repair, cell-cycle control, regulation of development, differentiation, and apoptosis. This observation agrees with other reports that many fundamental pathways related to tumor pathogenesis are inactivated by methylation.5,6,28,37,38 Our systematic analysis of a large cohort of patients with MDS and AML supports that aberrant methylation is a progressive process, noted in low-risk MDS and significantly increasing in extent with more advanced disease. Aberrant DNA methylation was seen in every sample and was more common and more extensive than chromosome abnormalities detected by a high-density SNP-A. The detected extent of chromosome aberrations is in keeping with studies using other techniques such as fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) for recurrent chromosome abnormalities.39 Genome-wide DNA sequencing of primary tissue to assess the contribution of mutation to TSG silencing is not generally practical. When the coding sequences of more than 13 000 genes were analyzed in breast and colon cancer cell lines and xenografts, the estimate was for approximately 80 amino acid–altering mutant genes accumulated in each individual tumor.40,41 Mutation rates may be higher in individual cancer cases (“mutator phenotype” cases), but overall, genomic instability at the chromosome level has been shown to be more prevalent than genomic instability at the nucleotide level.14

The extent and ubiquity of aberrant DNA methylation suggests that it could be the dominant force for TSG silencing and clonal variation that is then subject to positive selection in neoplastic evolution. While the widespread nature of aberrant hypermethylation suggests that some “passenger” or epi-phenomenom effect is plausible, the CpG sites represented in this array are believed to play a role in regulating gene expression,19 suggesting their methylation may well produce gene-expression changes that provide incremental competitive advantage. The association of methylation of specific genes with clinical outcome lends further support to the hypothesis that aberrant methylation plays a pathogenic role in MDS and its evolution to AML. In an effort to identify the biologically and clinically most relevant sites of promoter hypermethylation, we reasoned that concordantly (frequently) hypermethylated CpG sites/genes might be more likely to represent events that provide clonal advantage. In RAEB/AML, 51 CpG sites were hypermethylated in more than 50% of patients, and 5 genes (ALOX12, GSTM1, HIC1, FZD9, and HS3ST2) were hypermethylated in more than 70% of patients (methylation of HIC1 in MDS and AML has also been reported by others).26,42 We then examined if the methylation status of these sites predicted clinical outcomes. Analysis focused on FZD9 (frizzled 9), a receptor for Wnt in the Wnt pathway that is important in carcinogenesis.25 FZD9 methylation was an independent predictor of decreased survival. As an illustration of cooperation between chromosome aberrations and aberrant DNA methylation to completely silence TSGs, clinical outcome was poorest in patients with chromosome deletion of one allele of FZD9 and aberrant methylation of the remaining allele. This finding also suggests that in cases of chromosomal deletion, DNA methylation analysis of the remaining chromosome might identify a recessive TSG. Although studies to explain the mechanisms by which FZD9 repression impacts MDS and AML outcomes were beyond the scope of this study, the strong clinical correlations of FZD9 methylation suggests that it is at least one of the important TSGs on chromosome 7.

Loss of part of chromosome 7 (rather than the whole chromosome) is also frequently seen in MDS and AML and associated with a poor prognosis. We demonstrate that sometimes, small chromosome aberrations are confined to the 7q11 region that incorporates FZD9. However, there are more frequent deletions in the region of 7q22 and 7q33.17,43

The mechanisms responsible for producing aberrant DNA methylation are unknown. Only one of 3 CpG sites at the FZD9 locus was a frequent target of aberrant methylation, and only the methylated CpG site contained an E2F binding site. The E2F family has an important role in hematopoiesis, and E2F binding is prevented by DNA methylation44 ; however, we do not know if the E2F binding site is relevant to the aberrant methylation of this site. An analysis of the chromosome region around FZD9 demonstrated that methylation of this particular CpG site did not appear to be a part of propagated methylation of a wider chromosome region. Another possibility is that aberrant DNA methylation could in some way be triggered by chromosome instability. However, aberrant DNA methylation and complex cytogenetic abnormalities did not correlate to a statistically significant extent. Therefore, aberrant DNA methylation and cytogenetic abnormalities can cooperate to determine clinical outcome, but they appear to be mechanistically independent processes.

Other genes that were highly concordantly hypermethylated in RAEB/AML, including HIC1, ALOX12, and TNK1, were also noted to be frequently deleted or subject to UPD on SNP array analysis. TSP50 and NTRK1 were concordantly hypermethylated in all 3 disease groups analyzed (low-risk MDS, RAEB/AML, and CMML). Thus, it is possible that these 2 genes may be involved in pathogenetic steps that are common across the spectrum of myeloid malignancy. However, TSP50, which encodes a testis-specific protease, has been noted to be frequently hypomethylated in breast cancer.45 Therefore, aberrant DNA methylation may have differences between cancer histologies46 as well as pancancer similarities.47 NTRK1 is one of 3 known neurotrophic tyrosine kinase receptors and plays roles in cell differentiation, nervous system development, and tyrosine kinase signaling.48

Previous studies of specific methylated loci in MDS and AML have focused on genes such as p15, ER, and E-cadherin.11,26,29-32 In our analysis, frequent aberrant methylation was noted at CpG sites at each one of these gene loci, with the highest aberrant methylation rate being 48% for a CpG site in the p15 promoter. However, as discussed earlier, our broader analysis demonstrates that a number of other CpG sites at other gene loci were even more frequently aberrantly methylated. Even our study, limited to 1505 CpG sites, is only a reconnaissance into the extent and significance of aberrant methylation in leukemogenesis.

In conclusion, in this first comparison of high-throughput microarray promoter CpG methylation and SNP karyotyping analysis in MDS and AML; the ubiquity, extent, and progression of aberrant hypermethylation with disease stage suggests that it is the dominant source of TSG silencing and clonal variation in the neoplastic evolution of myeloid disease. This observation provides further incentive to the development and refinement of drug strategies to reverse aberrant DNA methylation.8-11 Methylation array analysis may identify candidate TSGs (eg, FZD9 on chromosome 7) that may account in part for the poor prognosis associated with deletions of certain chromosomes in myeloid malignancies. Accurate clinical insight into malignant disease stage and prognosis may benefit from routine measurement of aberrant methylation at specific loci.49,50

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01 HL082983 (J.P.M.), U54 RR019391 (J.P.M.), and K24 HL077522 (J.P.M.); a grant from AA and MDS International Foundation; and a charitable donation from the Robert Duggan Cancer Research Fund.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: Y.J. performed experiments, analyzed data, and prepared the manuscript; J.P.M. conceived the idea for this work, which was further developed by Y.S., obtained the funding, and together with Y.S. designed the experiments and supervised the work; Y.S. analyzed and interpreted the data and designed and wrote major portions of the manuscript; M.S. provided patient care and samples; and A.D., L.G., S.M., M.R., and C.O.K. performed some of the experiments and compiled the databases.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Yogen Saunthararajah or Jaroslaw P. Maciejewski, Taussig Cancer Institute/R40, 9500 Euclid Avenue, Cleveland, OH 44195; e-mail: saunthy@ccf.org or maciejj@ccf.org.

References

Author notes

*Y.S. and J.P.M. contributed equally to this work.