Abstract

The phagocyte NADPH oxidase generates superoxide for microbial killing, and includes a membrane-bound flavocytochrome b558 and cytosolic p67phox, p47phox, and p40phox subunits that undergo membrane translocation upon cellular activation. The function of p40phox, which binds p67phox in resting cells, is incompletely understood. Recent studies showed that phagocytosis-induced superoxide production is stimulated by p40phox and its binding to phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate (PI3P), a phosphoinositide enriched in membranes of internalized phagosomes. To better define the role of p40phox in FcγR-induced oxidase activation, we used immunofluorescence and real-time imaging of FcγR-induced phagocytosis. YFP-tagged p67phox and p40phox translocated to granulocyte phagosomes before phagosome internalization and accumulation of a probe for PI3P. p67phox and p47phox accumulation on nascent and internalized phagosomes did not require p40phox or PI3 kinase activity, although superoxide production before and after phagosome sealing was decreased by mutation of the p40phox PI3P-binding domain or wortmannin. Translocation of p40phox to nascent phagosomes required binding to p67phox but not PI3P, although the loss of PI3P binding reduced p40phox retention after phagosome internalization. We conclude that p40phox functions primarily to regulate FcγR-induced NADPH oxidase activity rather than assembly, and stimulates superoxide production via a PI3P signal that increases after phagosome internalization.

Introduction

Phagocytic leukocytes are the front-line cellular defense against microbial attack, and are mobilized rapidly to the sites of infection where they ingest and kill opsonized microorganisms. The NADPH oxidase complex plays a central role in this process, as its assembly and activation on phagosomal membranes generate superoxide, the precursor of potent microbicidal oxidants. The importance of this enzyme is demonstrated by genetic defects in the NADPH oxidase complex that cause chronic granulomatous disease (CGD), characterized by recurrent severe and potentially lethal bacterial and fungal infections.1

The NADPH oxidase includes the membrane-integrated flavocytochrome b, composed of gp91phox and p22phox, and the cytosolic components p47phox, p67phox, p40phox, and Rac, a Rho-family GTPase, which translocate to flavocytochrome b upon cellular stimulation to activate superoxide production.2–4 Segregation of regulatory components to the cytosol in resting cells facilitates the temporal and spatial regulation of NADPH oxidase activity. The p67phox subunit is a Rac-GTP effector2–4 containing a domain that activates electron transport through the flavocytochrome.5 In resting cells, p67phox is associated with p40phox via complementary PB1 (phagocyte oxidase and Bem1p) motifs present in each protein.2,6–8 p67phox is also linked to p47phox via a high-affinity interaction involving an SH3 domain and a proline-rich region, respectively, in the C-termini of these subunits.2–4,6,9 The p67phox, p47phox, and p40phox subunits can be isolated as a complex from neutrophil cytosol, and upon cellular activation, are believed to translocate as such to the flavocytochrome. p47phox plays a key role as a carrier protein as the other 2 cytosolic phox proteins fail to undergo membrane translocation in p47phox-deficient CGD neutrophils.10–12 Translocation to the flavocytochrome is mediated by a pair of SH3 domains within p47phox that are unmasked by activation-induced phosphorylation, which then bind to a proline-rich target sequence in p22phox.2–4,13

The role of p40phox, the most recently discovered NADPH oxidase subunit, has been controversial.14 Mutations in p40phox are not a cause of CGD,1 and p40phox is not required for high-level superoxide production in response to soluble agonists in either cell-free assays or whole-cell models.14–16 In addition to the PB1 domain that mediates binding to p67phox, p40phox has a PX (phox homology) and an SH3 domain. The physiologic target of the p40phox SH3 domain is uncertain, whereas the PX domain specifically binds phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate (PI3P), which is enriched in early endosomes17 and also appears on phagosomal membranes by the action of class III PI3 kinase (PI3K) within minutes of phagosome internalization in macrophages.18–22

Despite the importance of phagocytosis-induced superoxide production for host defense, the events regulating NADPH oxidase assembly and activation on the phagosome are incompletely defined. p47phox and p67phox are detected on the cup of newly forming phagosomes, and then on internalized phagosomes for many minutes after ingestion.11,23,24 Oxidant production can also begin on the plasma membrane and continues after phagosome internalization.4,25–27 Phagocytosis activates multiple signaling pathways, including PI3K's, although their specific roles are still being elucidated.3,4,28–32 FcγR ligation induces activation of class I PI3Ks early in phagocytosis, which generate PI(3,4,5)P and PI(3,4)P on the phagosome cup, and class III PI3K, which produces PI3P on internalized phagosomes.20 Following recognition that the PX domain of p40phox binds to PI3P,18–22 p40phox was established as an important regulator of phagocytosis-induced superoxide production.28,30,33,34 In COSphox cells with transgenes for flavocytochrome b, p47phox, p67phox, and the FcγIIA receptor, NADPH oxidase activity induced by phagocytosis of IgG-opsonized targets required coexpression of p40phox.30 In addition, superoxide production in response to IgG-opsonized particles and Staphylococcus aureus was substantially reduced in neutrophils and PLB-985 granulocytes lacking p40phox,28,34 and PI3P binding to p40phox was essential to stimulate phagosomal oxidase activity in both neutrophils and COSphox cells.28,30 In both the COSphox model and in permeabilized human neutrophils, mutants in the p40phox PB1 and SH3 domains, especially the double mutation, also impaired p40phox function, which suggests that binding of p40phox to p67phox as well as an additional target is required for regulation of FcγR-induced superoxide production.28,30,34

The underlying mechanism(s) by which p40phox regulates phagocytosis-activated superoxide production is not fully understood. p40phox has been proposed both to function as a second carrier protein that mediates recruitment of p67phox to PI3P-rich phagosome membranes29,35,36 and/or to regulate activity of the oxidase complex in combination with PI3P.22,28,29,34,37 To better define the role of p40phox in superoxide production during phagocytosis, we examined the dynamics of FcγR-induced p40phox accumulation on phagosomes and its coordination with NADPH oxidase assembly and activation, using both the COSphox model and videomicroscopy of PLB-985 neutrophils expressing fluorescently tagged phox subunits and/or the PX domain of p40phox, a robust probe for PI3P.

Methods

Reagents

Sheep red blood cell (SRBC) and rabbit anti-SRBC IgG were from MP Biomedicals (Solon, OH). Rabbit polyclonal p40phox antibody was from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY), and p67phox and p47phox mAbs were from BD Biosciences (Franklin Lakes, NJ). pEYFP-C1, pEYFP-N1, pMSCVpuro, and puromycin were from BD Clontech (Franklin Lakes, NJ), and pSuper(neo) plasmid from Oligoengine (Seattle, WA). Cell line nucleofector Kit V and Kit T were from Amaxa (Gaithersburg, MD). Bovine growth serum (BGS) and fetal calf serum (FCS) were from HyClone Laboratory (Logan, UT). Other tissue culture materials, Alexa-conjugated antibodies, and Bioparticle Opsonizing Reagent were from Invitrogen Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA). Hygromycin was from EMD Biosciences (San Diego, CA); G418, from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA); and ECL detection kit, from Pierce (Rockford, IL). Other reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO) unless stated.

Constructs for expression of fluorescence-tagged proteins

pEYFP-C1–based plasmids for expression of the YFP-tagged PX domain of p40phox (YFP-PX40) or for YFP-p40phox and mutant derivatives were described.21,30 Retroviral vectors to express YFP-p40phoxR105A, YFP-p40phoxW207R, and YFP-p40phoxD289A were generated by subcloning corresponding cDNAs into a modified pMSCVpuro lacking the PGK-puromycin cassette. A cDNA for p67phox tagged at its C-terminus with YFP was made using pEYFP-N1 and subcloned into pMSCVpac or derivative lacking the PGK-puromycin cassette. A cDNA encoding the p40phox PX domain with flanking EcoRI and KpnI restriction sites was generated by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of pEYFP-C1 containing YFP-PX40,21 which was ligated to the mCherry cDNA38 (gift of R. Tsien, University of California at San Diego) by insertion into a modified pEYFP-C1 (gift from J. Swanson, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor) in which the EYFP cDNA was replaced with that of mCherry. The mCherry-tagged PX40 cDNA was subcloned into pMSCVpuro and the PGK-puromycin cassette removed. Retroviral vectors were packaged using the Pantropic Retroviral Expression System (BD Clontech).

Cell lines and tissue culture

p67phox-YFP–expressing COS7 cell lines were made from COS7 cells expressing gp91phox, p22phox, p47phox, and FcγIIA receptor, in the presence or absence of a transgene for p40phox,16,30 by transducing with MSCV-p67YFP and sorting for YFP (FACSVantage; BD Biosciences). The 2 cell lines, called COSPF-p67YFP and COSPF40-p67YFP (PF = Phox FcγIIA), were cultured as described.30 Media for COSPF-p67YFP cells contained 0.2 mg/mL hygromycin, 0.8 mg/mL neomycin, and 1 μg/mL puromycin. Blasticidin (10 μg/mL) was included for COSPF40-p67YFP cells. Wild-type COS7 cells expressing a transgenic FcγIIA receptor (COS-WF cells) were described.30

PLB-985 cells expressing YFP-p40phox30 were transduced with MSCV-Cherry-PX40 to generate a derivative coexpressing Cherry-PX40. PLB-985 cells expressing fluorescently tagged p67phox or p40phox mutants were generated by transduction with MSCVpac-p67YFP, MSCV-YFP-p40phoxR105A, MSCV-YFP-p40phoxW207R, or MSCV-YFP-p40phoxD289A. The latter 3 were sorted by flow cytometry, whereas the former was selected in puromycin. PLB-985 lines were cultured and induced for neutrophil differentiation as described.39 To examine effects on translocation, pEYFP-C1 plasmids for expression of YFP-tagged p40phox mutants30 were transfected into neutrophil-differentiated PLB-985 cells with Amaxa Nucleofector kit T and program Y-0140 and incubated at 37°C for 3 hours before study.

Generation of p40phox-deficient PLB-985 cells

Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT, Coralville, IA) online program was used to design shRNA sequences targeting the human p40phox transcript: 546GGCAGCTCCGAGAGCAGAGGCTCTATT572 (H1), 69GGCCAACATTGCTGACATCGAGGAGAA95 (H2), and 684GGGCATCTTCCCTCTCTCCTTCGTGAA710 (H3). BglII and HindIII sites were added to each end of the hairpin. After ligation into pSuper(neo), each recombinant plasmid, or empty vector, was transfected into PLB-p67YFP cells using Amaxa nucleofector Kit V and program-23. Clones were selected with 1.5 mg/mL G418 and screened by Western blot for p40phox expression after neutrophil differentiation. Two of 6 clones selected for expression of the H3 shRNA showed a significant decrease in p40phox, and were used in described experiments. G418-selected PLB-p67YFP cells transfected with the empty pSuper(neo) vector were used as controls.

A pLL3.7-derived lentivirus carrying a hairpin targeting a 3′ untranslated sequence in the endogenous p40phox transcript, 5′-TGGAGATTGGGACCAGGAAATTCAAGAGATTTCCTGGTCCCAATCTCCTTTTTTC-3′,34 was used to transduce PLB-985, PLB-YFPp40, and PLB-YFPp40R105A cells and clones selected in 2 μg/mL puromycin. Two of 10 selected clones for each line showed a substantial decrease in endogenous p40phox expression in neutrophil-differentiated cells, and were used in experiments.

Western blotting

IgG-opsonized particles and assays for NADPH oxidase activity

SRBCs and 3.3-μm Latex beads were opsonized with human IgG as described.30 Zymosan A particles were opsonized with either Bioparticle Opsonizing Reagent (rabbit anti–zymosan IgG) according the manufacturer's instructions or with human IgG at 20 mg/mL at 37° for 60 minutes. Final stock solutions were prepared at 20 mg/mL in PBS and stored at −20°C until use.

NADPH oxidase activity was assayed using chemiluminescence enhanced by luminol or isoluminol, which is membrane-impermeant; both compounds detect superoxide in a peroxidase-dependent reaction.43,44 PLB-985 cells (2.5-5 × 105) or COS7-derived cells (2.5 × 105) in PBSG (PBS plus 0.9 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 20 mM dextrose) in the presence of 50 μM isoluminol or 50 μM luminol, without or with superoxide dismutase (SOD; final concentration: 75 μg/mL), were preincubated at 37°C for 10 minutes. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP; final concentration: 20 U/mL) was added to isoluminol assays and to luminol assays of COSphox lines. IgG-opsonized particles or phorbol myristate acetate (PMA, 300 ng/mL) was added to activate cells (final volume: 200 μL), and the relative light units (RLU) were monitored at 60- to 90-second intervals for up to 1 hour by the Long Kinetic module in an Lmax microplate luminometer from Molecular Devices (Sunnyvale, CA). Integrated RLU values were calculated by SOFTmax software (Molecular Devices). In some experiments, a synchronized phagocytosis protocol45 was adapted for NADPH oxidase assays. Briefly, PLB-985 neutrophils in 200 μL PBSG were incubated on ice for 5 minutes in 50 μM isoluminol and 20 U/mL HRP or 50 μM luminol, 75 μg/mL SOD, and 2000 U/mL catalase, then 25 μL cold IgG-zymosan (final concentration: 400 μg/mL) or cold IgG-Latex beads (cell:beads = 1:8) were added. Cells and particles were spun at 240g for 5 minutes at 4°C, then immediately placed at 37°C in the luminometer. For some experiments, cells were preincubated for 30 minutes at 37°C in the presence or absence of 100 nM wortmannin.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

COSPF-p67YFP, COSPF40-p67YFP, and COS7-WF cells were plated into coverslip-bottomed dishes (MatTek Cultureware, Ashland, MA) and incubated at 37°C for 24 hours, washed with fresh media, loaded with IgG-SRBCs prelabeled with goat Alexa-633 anti–rabbit IgG, incubated for 15 minutes at 37°C, and washed with cold PBS. After distilled water lysis of external SRBCs, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 minutes. Samples were permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS, blocked with 10% goat serum plus 2% BSA in PBS, and immunostained with anti-p47phox followed by Alexa-555 goat anti–mouse IgG. Nuclei were stained with 5 μg/mL DAPI in PBS for 5 minutes. Slides were imaged on a Zeiss LSM-510 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) using a 100×/1.4 NA oil-immersion objective. Samples were scanned sequentially at each excitation wavelength to minimize crosstalk between signals. Zeiss LSM software (Carl Zeiss) was used for image handling. Images shown are representative of at least 3 independent experiments.

Live cell imaging

A spinning-disk confocal system mounted on a Nikon TE-2000U inverted microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY) with an Ixon air-cooled EMCCD camera (Andor Technology, South Windsor, CT) and 100×/1.4 NA objective was used to film phagocytosis in living PLB-985 cells. Differentiated PLB-985 cells were loaded onto coverslip-bottomed dishes, which were mounted on the microscope and maintained at 37°C using a stage incubator (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT). After 3 minutes, IgG-zymosan was loaded into the dish. Videos were made over an approximately 30-minute interval after the addition of IgG-zymosan. Fields were monitored randomly to identify cells beginning to ingest a particle, and sequential images collected with 488 nm and/or 568 nm excitation and 0.3-second exposure with a time lapse of 5 or 10 seconds for 5 to 8 minutes. Phagosomes being filmed often moved out of the focal plane, so a new cell beginning to ingest a particle was identified for filming. MetaMorph (Universal Imaging, Downington, PA) was used for image handling. Images shown are representative of at least 4 independent experiments except for studies on PLB-985 neutrophils transiently expressing YFP-p40phoxW207R or YFP-p40phoxD289A, which were performed 2 and 3 times, respectively.

To further assess translocation of fluorescent probes, images were analyzed using Image J (National Institutes of Health [NIH], Bethesda, MD). An area of the phagosome rim (≈ 25% of the total rim) was outlined by hand, and the mean fluorescence intensity within the area determined, and ratios were determined against the value from a corresponding area in the cytoplasm near the phagosome. At least 5 phagosomes monitored at each stage—cup, closure (time of sealing), and after internalization (200-300 seconds after closure, or 120 seconds after closure for YFP-p40phox R105A and for wortmannin-treated cells)—were analyzed by this method and the mean plus or minus SEM was determined.

Results

Recruitment of p67phox and p47phox to phagosomes is independent of p40phox in COSphox cells

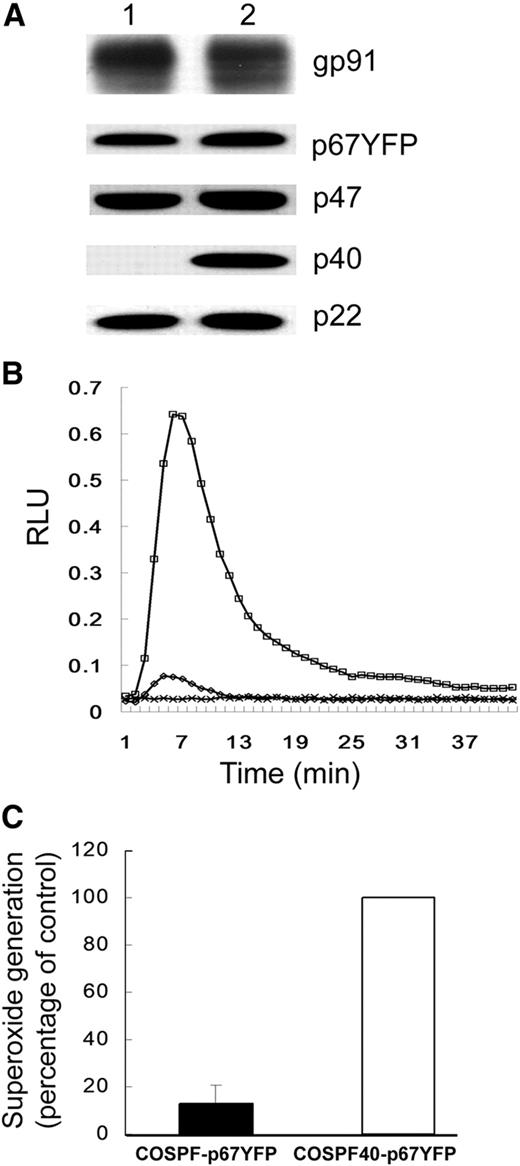

We examined whether expression of p40phox is required for recruitment of p67phox and p47phox to phagosomes in the COSphox model. To facilitate imaging, COS7 cells were generated that stably expressed p67phox-YFP along with gp91phox, p22phox, p47phox, and the FcγIIA receptor, without or with coexpression of p40phox (Figure 1A). Previous studies showed that p67phox tagged in this manner supports NADPH oxidase activity at levels similar to untagged p67phox.23 In NADPH oxidase assays using luminol-enhanced chemiluminescence, although both lines responded similarly to PMA stimulation (Figure S1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article), there was very little IgG-SRBC–stimulated superoxide in the absence of p40phox (Figure 1B,C), confirming our previous study.30

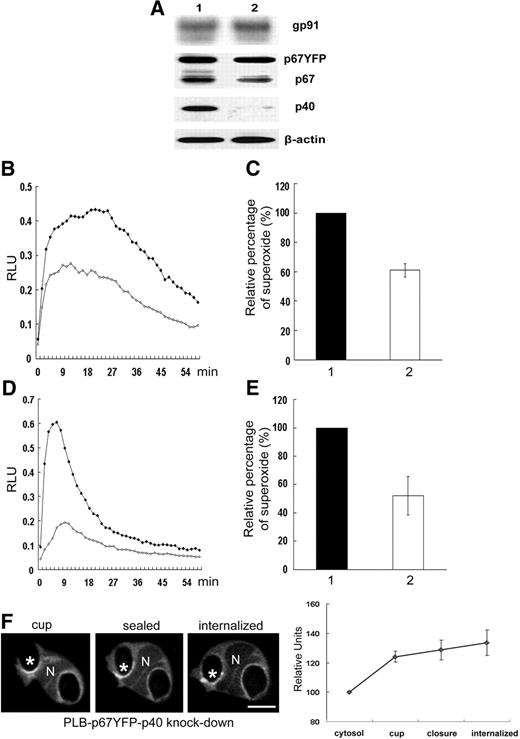

NADPH oxidase activity in COS7 transgenic cells. (A) Western blot analysis of COSPF-p67YFP (lane 1) and COSPF40-p67YFP (lane 2) cell lysates probed for expression of the indicated phox proteins. (B) Representative result of luminol assay for superoxide production in COSphox cells during phagocytosis of IgG-opsonized SRBCs. □ indicates COSPF40-p67YFP; ◇, COSPF-p67YFP; and x, COS-WF. (C) Integrated RLU values for luminol assays of indicated cell lines (mean ± SD, n = 12).

NADPH oxidase activity in COS7 transgenic cells. (A) Western blot analysis of COSPF-p67YFP (lane 1) and COSPF40-p67YFP (lane 2) cell lysates probed for expression of the indicated phox proteins. (B) Representative result of luminol assay for superoxide production in COSphox cells during phagocytosis of IgG-opsonized SRBCs. □ indicates COSPF40-p67YFP; ◇, COSPF-p67YFP; and x, COS-WF. (C) Integrated RLU values for luminol assays of indicated cell lines (mean ± SD, n = 12).

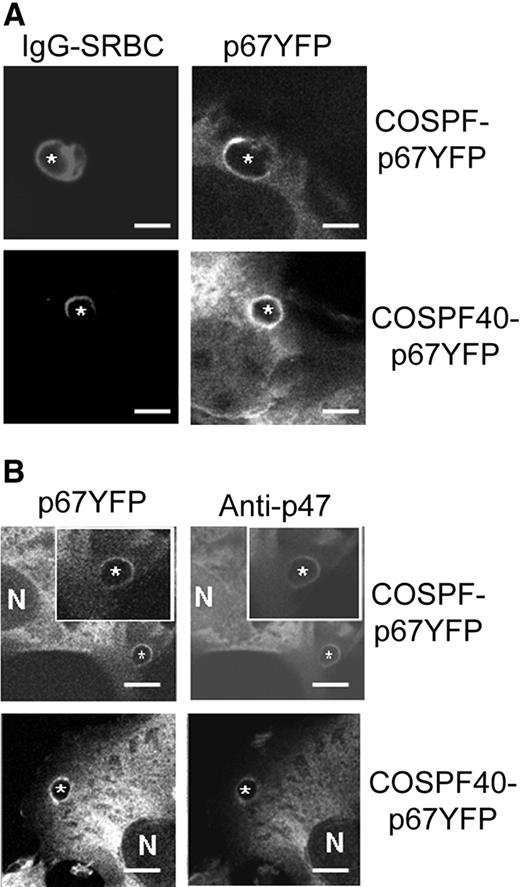

Next, the fate of p67phox-YFP was monitored by confocal microscopy in COSPF-p67YFP and COSPF40-p67YFP cells incubated with IgG-SRBCs. The results showed that p67phox-YFP was present on phagosomes in both COSPF-p67YFP and COSPF40-p67YFP cells (Figure 2). Indirect immunofluorescence showed that p47phox colocalized with p67phox-YFP on phagosomes in both cell lines (Figure 2B; Figure S2), consistent with the concept that p47phox and p67phox are tightly linked via a tail-to-tail interaction and translocate as a unit.2,6,9,46 No p47phox staining was observed in control COS-WF cells (Figure S2). These data indicate that although FcγR-activated superoxide production has a strong requirement for p40phox in COSphox cells, the absence of p40phox does not prevent phagosomal translocation of p47phox and p67phox.

Translocation of p67phox-YFP and p47phox during phagocytosis of IgG-SRBCs by COS7 transgenic cells. IgG-SRBCs were fed to the indicated COSphox cells growing on coverslip-bottomed dishes. N shows the location of nucleus and asterisks indicate the IgG-SRBC phagosomes. Bar represents 5 μm. (A) Images of Alexa-633–labeled IgG-SRBCs and p67phox-YFP after fixation and analysis by confocal microscopy as described in “Immunofluorescence microscopy.” (B) Simultaneous imaging of p67phox-YFP and p47phox after immunofluorescent staining with anti-p47phox mAb and Alexa-555 goat anti–mouse IgG.

Translocation of p67phox-YFP and p47phox during phagocytosis of IgG-SRBCs by COS7 transgenic cells. IgG-SRBCs were fed to the indicated COSphox cells growing on coverslip-bottomed dishes. N shows the location of nucleus and asterisks indicate the IgG-SRBC phagosomes. Bar represents 5 μm. (A) Images of Alexa-633–labeled IgG-SRBCs and p67phox-YFP after fixation and analysis by confocal microscopy as described in “Immunofluorescence microscopy.” (B) Simultaneous imaging of p67phox-YFP and p47phox after immunofluorescent staining with anti-p47phox mAb and Alexa-555 goat anti–mouse IgG.

NADPH oxidase activation and translocation of p67phox-YFP and YFP-p40phox during phagocytosis in PLB-985 neutrophils

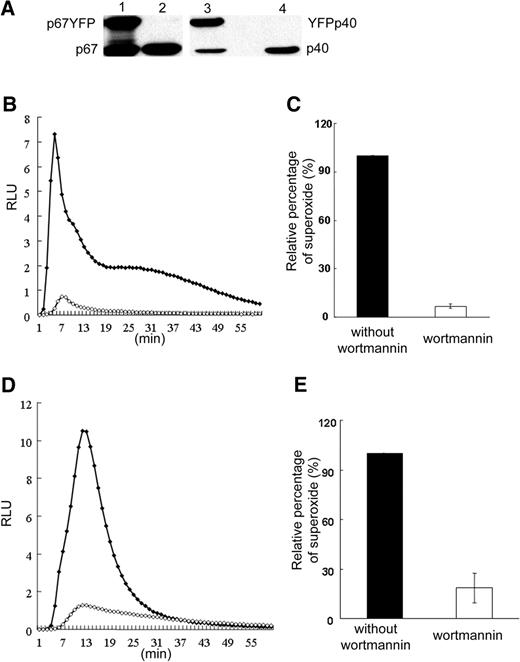

Assembly and activation of the NADPH oxidase complex was studied in neutrophil-differentiated PLB-985 cells expressing YFP-p40phox (PLB-YFPp40) or p67phox-YFP (PLB-p67YFP). Endogenous and YFP-tagged subunits were expressed at comparable levels (Figure 3A and data not shown). IgG-zymosan–induced NADPH oxidase activity in PLB-p67YFP neutrophils was assayed where particles were bound to cells at 4°C followed by warming to 37°C to initiate phagocytosis. Superoxide production began before sealing of phagosomes, as detected by isoluminol-enhanced chemiluminescence (Figure 3B,C), although the magnitude of this response is small in comparison to extracellular superoxide detected following fMLP (not shown) or PMA (Figure S3A) stimulation. Peak rates of superoxide release occurred within minutes of warming, then declined to lower levels. NADPH oxidase activity in internalized phagosomes was detected using luminol in the presence of SOD and catalase (Figure 3D,E), with peak rates shifted in time compared with isoluminol. IgG-zymosan–induced NADPH oxidase activity both before and after phagosome internalization was substantially decreased by 100 nM wortmannin (Figure 3B-D). Of note, wortmannin had no effect on the ability of PLB-985 neutrophils to ingest IgG-zymosan particles (average of 1.9 phagosomes per cell in 50 to 65 cells analyzed in videos of untreated and wortmannin-treated cells). IgG-zymosan–stimulated superoxide production and wortmannin sensitivity of parental PLB-985 cells and PLB-YFPp40 were similar to PLB-p67YFP cells (not shown). Finally, as previously reported by many groups (eg, Arcaro and Wymann47 ; Laudanna et al48 ), wortmannin had no effect on PMA-induced NADPH oxidase activity (Figure S3B).

NADPH oxidase activity in neutrophil-differentiated PLB-985 cells expressing YFP-phox proteins during phagocytosis of IgG-zymosan. (A) Western blot analysis of exogenous YFP-tagged phox proteins and endogenous phox proteins in PLB-985 neutrophil lysates. Lane 1 shows PLB-p67YFP; lane 2, PLB-985; lane 3, PLB-YFPp40; and lane 4, PLB-985. (B-E) NADPH oxidase activity in PLB-p67YFP neutrophils during synchronized phagocytosis of IgG-zymosan was quantified using isoluminol in the presence of HRP (B,C) to detect extracellular superoxide or luminol in the presence of SOD and catalase (D,E) to detect intracellular activity. Assays were performed in the absence or presence of preincubation with 100 nM wortmannin, as indicated. Representative kinetic plots (B,D) and mean plus or minus SD of relative integrated RLU data are shown (3 assays). The activity profile was similar for PLB-p67YFP and PLB-YFPp40 cells (data not shown). ♦ indicates no wortmannin; ◇, 100 nM wortmannin.

NADPH oxidase activity in neutrophil-differentiated PLB-985 cells expressing YFP-phox proteins during phagocytosis of IgG-zymosan. (A) Western blot analysis of exogenous YFP-tagged phox proteins and endogenous phox proteins in PLB-985 neutrophil lysates. Lane 1 shows PLB-p67YFP; lane 2, PLB-985; lane 3, PLB-YFPp40; and lane 4, PLB-985. (B-E) NADPH oxidase activity in PLB-p67YFP neutrophils during synchronized phagocytosis of IgG-zymosan was quantified using isoluminol in the presence of HRP (B,C) to detect extracellular superoxide or luminol in the presence of SOD and catalase (D,E) to detect intracellular activity. Assays were performed in the absence or presence of preincubation with 100 nM wortmannin, as indicated. Representative kinetic plots (B,D) and mean plus or minus SD of relative integrated RLU data are shown (3 assays). The activity profile was similar for PLB-p67YFP and PLB-YFPp40 cells (data not shown). ♦ indicates no wortmannin; ◇, 100 nM wortmannin.

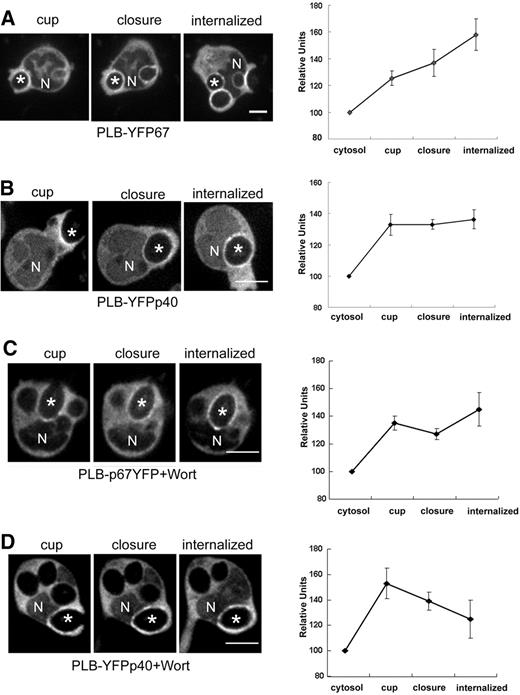

Time-lapse confocal videomicroscopy was used to monitor recruitment of YFP-p40phox and p67phox-YFP to phagosomes during ingestion of IgG-zymosan by PLB-985 neutrophils (Figure 4A,B; Videos S1,S2). Both p67phox-YFP and YFP-p40phox, which were otherwise distributed homogenously in the cytoplasm, accumulated on the phagosomal cup, visible 40 to 60 seconds before phagosome closure (sealing), and probes remained detectable on phagosomes for at least 5 minutes after closure. Accumulation of fluorescently tagged phox subunits often appeared nonuniform and/or “clumpy” (Figures 4,Figure 5,Figure 6–7 and Videos S1Video 2. Time-lapse movie of PLB-YFPp40 cells corresponding to the sequence shown in Figure 4B (MOV, 598 KB)Video 3. Time-lapse movie of wortmannin-treated PLB-p67YFP cells corresponding to the sequence shown in Figure 4C (MOV, 239 KB)Video 4. Time-lapse movie of wortmannin-treated PLB-YFPp40 cells corresponding to the sequence shown in Figure 4C (MOV, 1.10 MB)Video 5. Time-lapse movie of PLB-p67YFP-p40siRNA cells corresponding to the sequence shown in Figure 5F (MOV, 172 KB)Video 6. Time-lapse movie of PLB-YFPp40/Cherry-PX cells corresponding to the sequence shown in Figure 6A and showing YFPp40 (MOV, 605 KB)Video 7. Time-lapse movie of PLB-YFPp40/Cherry-PX cells corresponding to the sequence shown in Figure 6A and showing Cherry-PX (MOV, 1.02 MB)–S8). Although superoxide production was strongly dependent on PI3K activity (Figure 3B), wortmannin did not prevent recruitment of either p67phox-YFP or YFP-p40phox to nascent phagosomes (Figure 4C,D; Videos S3,S4). Interestingly, although p67phox-YFP accumulation persisted after internalization, we observed that p40phox-YFP accumulation disappeared in 2 of 7 phagosomes within 2 minutes after sealing, leading to a decline in average fluorescence intensity of the p40phox-YFP probe (Figure 4D).

Translocation of YFP-tagged p67phox and p40phox during phagocytosis of IgG-zymosan in the presence and absence of wortmannin. Time-lapse confocal microscopy was used to monitor phagocytosis of IgG-zymosan by PLB-985 neutrophils expressing YFP-tagged p67phox or p40phox (Videos S1Video 2. Time-lapse movie of PLB-YFPp40 cells corresponding to the sequence shown in Figure 4B (MOV, 598 KB)Video 3. Time-lapse movie of wortmannin-treated PLB-p67YFP cells corresponding to the sequence shown in Figure 4C (MOV, 239 KB)–S4). N shows the location of nucleus and asterisks indicate the IgG-zymosan phagosomes monitored. Bar represents 5 μm. (A,B) PLB-p67YFP and PLB-YFPp40 cells. The relative fluorescence intensity compared with the cytosol for 5 phagosomes at indicated stages is shown in the graphs, as mean plus or minus SE. Internalized indicates 200 or more seconds after phagosome closure. (C,D) PLB-p67YFP and PLB-YFPp40 neutrophils pretreated with 100 nM wortmannin before incubation with IgG-zymosan. N shows the location of nucleus and asterisks indicate the IgG-zymosan phagosomes monitored. Bar represents 5 μm. The relative fluorescence intensity compared with the cytosol for 5 to 7 phagosomes at indicated stages is shown in the graphs, as mean plus or minus SE. Internalized indicates 120 or more seconds after phagosome closure.

Translocation of YFP-tagged p67phox and p40phox during phagocytosis of IgG-zymosan in the presence and absence of wortmannin. Time-lapse confocal microscopy was used to monitor phagocytosis of IgG-zymosan by PLB-985 neutrophils expressing YFP-tagged p67phox or p40phox (Videos S1Video 2. Time-lapse movie of PLB-YFPp40 cells corresponding to the sequence shown in Figure 4B (MOV, 598 KB)Video 3. Time-lapse movie of wortmannin-treated PLB-p67YFP cells corresponding to the sequence shown in Figure 4C (MOV, 239 KB)–S4). N shows the location of nucleus and asterisks indicate the IgG-zymosan phagosomes monitored. Bar represents 5 μm. (A,B) PLB-p67YFP and PLB-YFPp40 cells. The relative fluorescence intensity compared with the cytosol for 5 phagosomes at indicated stages is shown in the graphs, as mean plus or minus SE. Internalized indicates 200 or more seconds after phagosome closure. (C,D) PLB-p67YFP and PLB-YFPp40 neutrophils pretreated with 100 nM wortmannin before incubation with IgG-zymosan. N shows the location of nucleus and asterisks indicate the IgG-zymosan phagosomes monitored. Bar represents 5 μm. The relative fluorescence intensity compared with the cytosol for 5 to 7 phagosomes at indicated stages is shown in the graphs, as mean plus or minus SE. Internalized indicates 120 or more seconds after phagosome closure.

Effect of shRNA knockdown of p40phox on NADPH oxidase activity in neutrophil-differentiated PLB-p67YFP cells. PLB-p67YFP cell lines induced for neutrophil differentiation were analyzed by Western blot (A) for the expression of NADPH oxidase subunits and for NADPH oxidase activity during phagocytosis of IgG-zymosan (B-E). Lane 1 shows PLB-p67YFP-pSuper(neo) (empty vector) cells; lane 2, PLB-p67YFP p40phox knockdown cells. NADPH oxidase assays were performed using isoluminol in the presence of HRP (B,C) to detect extracellular superoxide or luminol in the presence of SOD (D,E) to detect intracellular activity. Representative kinetic plots (B,D) and mean plus or minus SD of relative integrated RLU data are shown (2 isoluminol assays and 4-6 luminol assays). ♦ indicates PLB-p67YFP; ◇, PLB-p67YFP with p40phox knockdown. (F) Time-lapse confocal images of p67phox-YFP in p40phox knockdown cells (Video S5). The relative fluorescence intensity compared with the cytosol for 5 phagosomes at indicated stages is shown in the graph, as mean plus or minus SE. N shows the location of nucleus and asterisks indicate the IgG-zymosan phagosomes monitored. Bar represents 5 μm.

Effect of shRNA knockdown of p40phox on NADPH oxidase activity in neutrophil-differentiated PLB-p67YFP cells. PLB-p67YFP cell lines induced for neutrophil differentiation were analyzed by Western blot (A) for the expression of NADPH oxidase subunits and for NADPH oxidase activity during phagocytosis of IgG-zymosan (B-E). Lane 1 shows PLB-p67YFP-pSuper(neo) (empty vector) cells; lane 2, PLB-p67YFP p40phox knockdown cells. NADPH oxidase assays were performed using isoluminol in the presence of HRP (B,C) to detect extracellular superoxide or luminol in the presence of SOD (D,E) to detect intracellular activity. Representative kinetic plots (B,D) and mean plus or minus SD of relative integrated RLU data are shown (2 isoluminol assays and 4-6 luminol assays). ♦ indicates PLB-p67YFP; ◇, PLB-p67YFP with p40phox knockdown. (F) Time-lapse confocal images of p67phox-YFP in p40phox knockdown cells (Video S5). The relative fluorescence intensity compared with the cytosol for 5 phagosomes at indicated stages is shown in the graph, as mean plus or minus SE. N shows the location of nucleus and asterisks indicate the IgG-zymosan phagosomes monitored. Bar represents 5 μm.

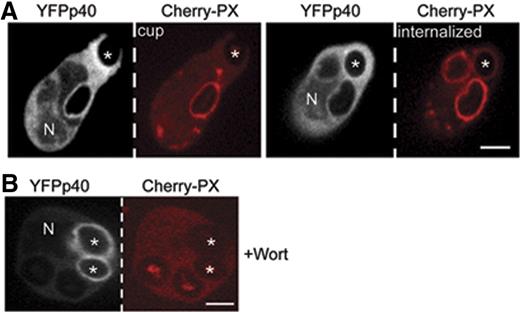

p40phox accumulates on to the phagosome independent of PI3P. Time-lapse confocal microscopy was used to monitor translocation of coexpressed YFP-p40phox and Cherry-PX40 in PLB-985 cells during phagocytosis of IgG-zymosan in the absence (A) and presence (B) of 100 nM wortmannin (Videos S6,S7). YFP-p40phox is detected on the cup, whereas Cherry-PX40 appears after closure (A). Cherry-PX40 does not accumulate in wortmannin-treated cells, although YFP-p40phox is present on internalized phagosomes (see also Figure 4D). N shows the location of nucleus in the YFP-p40phox panel. Phagosome stages are indicated and asterisks show the IgG-zymosan phagosomes monitored. Bar represents 5 μm.

p40phox accumulates on to the phagosome independent of PI3P. Time-lapse confocal microscopy was used to monitor translocation of coexpressed YFP-p40phox and Cherry-PX40 in PLB-985 cells during phagocytosis of IgG-zymosan in the absence (A) and presence (B) of 100 nM wortmannin (Videos S6,S7). YFP-p40phox is detected on the cup, whereas Cherry-PX40 appears after closure (A). Cherry-PX40 does not accumulate in wortmannin-treated cells, although YFP-p40phox is present on internalized phagosomes (see also Figure 4D). N shows the location of nucleus in the YFP-p40phox panel. Phagosome stages are indicated and asterisks show the IgG-zymosan phagosomes monitored. Bar represents 5 μm.

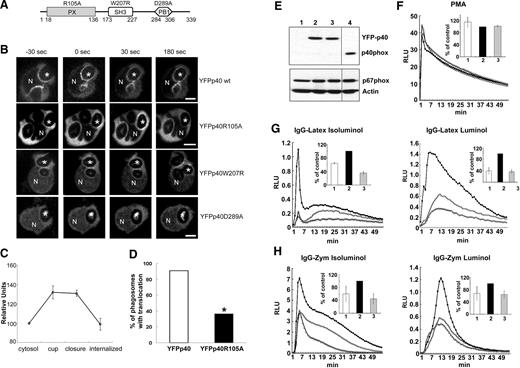

Effects of p40phox mutations in the PX, SH3, and PB1 domains on translocation of p40phox to the phagosome. (A) Schematic illustration of domains within p40phox and mutants studied for translocation in PLB-985 neutrophils. (B) Time-lapse confocal microscopy was used to monitor translocation of wild-type YFP-p40phox and indicated YFP-p40phox mutants in PLB-985 neutrophils. In the experiments shown, all but YFP-p40phoxR105A were expressed using a transient transfection method. Wild-type YFP-p40phox, YFP-p40phoxR105A, and YFP-p40phoxW207R accumulate on the phagosomal cup but YFP-p40phoxD289A does not. N shows the nucleus and asterisks indicate the IgG-zymosan phagosomes monitored. Bar represents 5 μm. (C) The relative fluorescence intensity compared with the cytosol for 5 phagosomes in PLB-YFPp40 R105A cells at indicated stages is shown in the graphs, as mean plus or minus SD. Internalized indicates 120 seconds after phagosome closure. (D) Phagosomes exhibiting translocation of either YFP-p40phox or YPF-p40phoxR105A in the phagosomal cup were scored for persistence of translocation at 3 minutes after closure. The percentage of phagosomes showing persistent translocation of p40phoxR105A was significantly lower than for YPF-p40phox (*P < .03, n = 11 phagosomes in each group; Fisher exact test). (E-H) A lentiviral vector expressing an shRNA from the 3′ untranslated region of the p40phox cDNA was used to transduce PLB-985, PLB-YFPp40, or PLB-YFPp40R105A cells to generate p40phox knockdown (p40KD PLB-985) cells deficient in endogenous p40phox. (E) Western blot analysis of YFP-tagged proteins and endogenous p40phox, p67phox, and actin in PLB-985 neutrophil lysates. Lane 1 shows p40KD PLB-985; lane 2, p40KD PLB-YFPp40; lane 3, p40KD PLB-YFPp40R105A, and lane 4, PLB-985. A vertical line has been inserted to indicate a repositioned gel lane. (F-H) NADPH oxidase activity in neutrophil-differentiated p40KD PLB-985 cell lines. 1 or ◇ indicates p40KD PLB-985; 2 or ■, p40KD PLB-YFPp40; and 3 or ▵, p40KD PLB-YFPp40R105A. (F) PMA-induced superoxide release detected by isoluminol. The insert represents the mean plus or minus SD (total RLU value over 54 minutes, measured at 1-minute intervals) of 2 independent experiments. (G-H) Extracellular (isoluminol) and intracellular (luminol plus SOD and catalase) superoxide production during synchronized phagocytosis of IgG-Latex beads (G) or IgG-Zym (H). The insert represents the mean plus or minus SD (total RLU value over 54 minutes, measured at 1-minute intervals) of 3 independent experiments.

Effects of p40phox mutations in the PX, SH3, and PB1 domains on translocation of p40phox to the phagosome. (A) Schematic illustration of domains within p40phox and mutants studied for translocation in PLB-985 neutrophils. (B) Time-lapse confocal microscopy was used to monitor translocation of wild-type YFP-p40phox and indicated YFP-p40phox mutants in PLB-985 neutrophils. In the experiments shown, all but YFP-p40phoxR105A were expressed using a transient transfection method. Wild-type YFP-p40phox, YFP-p40phoxR105A, and YFP-p40phoxW207R accumulate on the phagosomal cup but YFP-p40phoxD289A does not. N shows the nucleus and asterisks indicate the IgG-zymosan phagosomes monitored. Bar represents 5 μm. (C) The relative fluorescence intensity compared with the cytosol for 5 phagosomes in PLB-YFPp40 R105A cells at indicated stages is shown in the graphs, as mean plus or minus SD. Internalized indicates 120 seconds after phagosome closure. (D) Phagosomes exhibiting translocation of either YFP-p40phox or YPF-p40phoxR105A in the phagosomal cup were scored for persistence of translocation at 3 minutes after closure. The percentage of phagosomes showing persistent translocation of p40phoxR105A was significantly lower than for YPF-p40phox (*P < .03, n = 11 phagosomes in each group; Fisher exact test). (E-H) A lentiviral vector expressing an shRNA from the 3′ untranslated region of the p40phox cDNA was used to transduce PLB-985, PLB-YFPp40, or PLB-YFPp40R105A cells to generate p40phox knockdown (p40KD PLB-985) cells deficient in endogenous p40phox. (E) Western blot analysis of YFP-tagged proteins and endogenous p40phox, p67phox, and actin in PLB-985 neutrophil lysates. Lane 1 shows p40KD PLB-985; lane 2, p40KD PLB-YFPp40; lane 3, p40KD PLB-YFPp40R105A, and lane 4, PLB-985. A vertical line has been inserted to indicate a repositioned gel lane. (F-H) NADPH oxidase activity in neutrophil-differentiated p40KD PLB-985 cell lines. 1 or ◇ indicates p40KD PLB-985; 2 or ■, p40KD PLB-YFPp40; and 3 or ▵, p40KD PLB-YFPp40R105A. (F) PMA-induced superoxide release detected by isoluminol. The insert represents the mean plus or minus SD (total RLU value over 54 minutes, measured at 1-minute intervals) of 2 independent experiments. (G-H) Extracellular (isoluminol) and intracellular (luminol plus SOD and catalase) superoxide production during synchronized phagocytosis of IgG-Latex beads (G) or IgG-Zym (H). The insert represents the mean plus or minus SD (total RLU value over 54 minutes, measured at 1-minute intervals) of 3 independent experiments.

NADPH oxidase assembly and activation on phagosomes were next analyzed in p40phox-deficient PLB-p67YFP cells generated using a p40phox-targeted shRNA. Western blotting showed a substantial decrease in p40phox and a small reduction in endogenous p67phox, similar to previous studies in p40phox-deficient mouse neutrophils,28 but expression of YFP-tagged p67phox appeared to be unaffected (Figure 5A). Similar to previous studies,28,33,34 superoxide production in internalized phagosomes was reduced by approximately 2-fold in p40phox-deficient PLB-p67YFP cells stimulated with either IgG-zymosan (Figure 5D,E) or IgG-opsonized Latex beads (not shown). Superoxide production before phagosome sealing was also reduced by approximately 40% (Figure 5B,C). However, p67phox-YFP accumulated on the phagosomal cup in p40phox-deficient PLB-p67YFP cells and persisted for at least 5 minutes after closure (Figure 5F; Video S5), similar to PLB-p67YFP cells that express endogenous p40phox (Figure 4A). The independence of p67phox-YFP translocation on p40phox is consistent with our findings in COSphox cells (Figure 2), and supports a model in which translocation of p67phox to nascent and internalized phagosomes does not require p40phox.

Role of PI3P and the PX, SH3, and PB1 domains of p40phox in FcγR-induced p40phox translocation to phagosomes

The appearance of YFP-p40phox in the phagosomal cup before the expected accumulation of phagosomal PI3P, which in macrophages occurs after phagosome internalization,18–20 and its insensitivity to wortmannin suggested that the initial recruitment of p40phox to phagosomes does not require binding to PI3P. To directly examine the temporal relationship between the appearance of p40phox and PI3P on neutrophil phagosomes, phagocytosis was analyzed in PLB-YFPp40 neutrophils coexpressing the p40phox PX domain (PX40), a probe for PI3P,18 tagged with mCherry. Although YFP-p40phox was detected on the phagosomal cup, Cherry-PX40 did not accumulate until 40 to 60 seconds after the phagosome was sealed and internalized (Figure 6A; Videos S6,S7). Preincubation of cells in 100 nM wortmannin abolished accumulation of Cherry-PX40, consistent with a requirement for PI3K to generate PI3P,18,19 but YFP-p40phox was still present on many phagosomes (Figure 6B). These results further establish that recruitment of p40phox is not mediated by PI3P.

The role of each of the 3 p40phox modular domains in translocation to phagosomes was examined by expressing YFP-tagged p40phox mutants (Figure 7A) in PLB-985 neutrophils. These included a PX domain mutant, R105A, that eliminates binding to PI3P, the SH3 domain mutant W207R, and a PB1 domain mutant, D289A, that prevents binding of p40phox to p67phox.2,30,49,50 The p40phoxD289A mutant was poorly expressed from a stable transgene in PLB-985 granulocytes, most likely because binding to p67phox is important for p40phox stability in neutrophils, as inferred from studies of p67phox-deficient CGD neutrophils which have markedly reduced levels of p40phox14 ; p40phoxW207R was also poorly expressed in PLB-985 granulocytes, for uncertain reasons (Figure S4). Thus, we used a transient expression protocol developed for neutrophils40 to study translocation of W207R, D289A, and a double W207R/D289A p40phox mutant in comparison with wild-type p40phox. Translocation of p40phoxR105A was studied both as a transiently expressed protein and as expressed from a stable transgene, with similar results. Note that although an R57Q PI3P-binding mutant of p40phox was enriched in the Triton X-100–insoluble fraction,42 this was not observed for p40phoxR105A (Figure S4).

Imaging by confocal videomicroscopy showed that R105A and W207R YFP-p40phox mutants were recruited to the phagosomal cup, similar to wild-type YFP-p40phox (Figure 7B,C). In contrast, YFP-p40phox derivatives with a mutation that prevents binding to p67phox, D289A, and W207R/D289A YFP-p40phox were rarely detected on phagosomes, either before or after phagosome closure (Figure 7B and data not shown). For example, D289A YFP-p40phox translocation was seen in only 2 of 30 phagosomes analyzed. Wild-type YPP-p40phox and W207R YFP-p40phox were present on internalized phagosomes, similar to previous observations in the COSphox model.30 However, although the PI3P-binding mutant R105A YFP-p40phox appeared on nascent phagosomes, it often disappeared within minutes after closure (Figure 7B-D). In phagosomes followed from time of cup formation, R105A YFP-p40phox was present on only approximately one third of internalized phagosomes for longer than 3 minutes after sealing, in contrast to wild-type YFP-p40phox (P < .03; Fisher exact test; Figure 7D). In contrast, a similar analysis in p40phox-deficient PLB-p67YFP cells found that p67phox-YFP was detected on 11 of 11 phagosomes monitored for at least 3 minutes after phagosome closure (see also Figure 5F; Video S5). These data indicate that the PB1 domain–mediated interaction between p40phox and p67phox is required for recruitment of p40phox, but not p67phox, to both nascent and internalized phagosomes, even with an intact binding site for PI3P in p40phox. However, p40phox binding to PI3P appears to partially influence whether p40phox is present on phagosomal membranes after internalization. This effect is more pronounced compared with wortmannin treatment, which may reflect an influence of other wortmannin-inhibited pathways.

Role of the p40phox PX domain in FcγR-induced NADPH oxidase activity

To examine how loss of PI3P binding by p40phox affects NADPH oxidase activity, PLB-985, PLB-YFPp40, or PLB-YFPp40R105A cells were made deficient in endogenous p40phox using an shRNA targeting the 3′ untranslated region34 (Figure 7E). As in a previous study using this shRNA,34 p67phox expression in neutrophil-differentiated p40phox knockdown (p40KD) PLB-985 lines was similar to PLB-985 cells (Figure 7E). PMA-induced superoxide release in p40KD PLB-985 cells was robust and similar to p40KD PLB-985 cells expressing YFP-p40phox or YFP-p40phoxR105A. However, IgG-particle–activated superoxide production both before and after phagosome internalization was decreased by at least 40% in p40KD cells and p40KD cells expressing YFP-p40phoxR105A, compared with p40KD cells expressing YFP-p40phox (Figure 7F). Indeed, expression of YFP-p40phoxR105A tended to decrease activity to a greater extent than p40KD alone, suggestive of an inhibitory effect. Similar to studies in PLB-985 cells (Figure 7B-D), the R105A mutation did not prevent p40phox translocation to nascent phagosomes in p40KD cells (Video S8), consistent with the concept that although PI3P binding to p40phox stimulates enzyme activity, it is not required for initial p40phox translocation. However, as in Figure 7B-D, YFP-p40R105A often disappeared from internalized phagosomes in p40KD cells; of 8 phagosomes analyzed from time of cup formation, YFP-p40R105A was present on only 3 for longer than 3 minutes (see also Video S8).

Discussion

PI3Ks products play important roles in regulating superoxide production during phagocytosis, particularly PI3P that is enriched in membranes of internalized phagosomes and whose effects on NADPH oxidase activity are mediated via p40phox.28–30,33,34 The current study used real-time imaging of phagocytosis of IgG-opsonized particles to analyze assembly of the NADPH oxidase complex in neutrophil-differentiated PLB-985 cells. Particular emphasis was given to investigating the recruitment of the cytosolic NADPH oxidase subunits, p40phox and p67phox, and the relationship between their translocation, the accumulation of PI3P, and superoxide production, to better characterize the role of p40phox, which has high-affinity binding domains for both p67phox and PI3P.

This study confirms previous reports that p67phox is recruited to nascent granulocyte phagosomes and is present after internalization,11,23,51 and shows for the first time that p40phox translocation during phagocytosis exhibits similar behavior and fails to accumulate on phagosomes if unable to bind to p67phox. Conversely, p40phox was not required for accumulation of p67phox and p47phox on IgG-zymosan phagosomes in COSphox cells expressing FcγIIA, although NADPH oxidase activity was minimal unless p40phox was coexpressed. Translocation of p67phox on nascent and internalized phagosomes was also observed in p40phox-deficient PLB-985 neutrophils. Furthermore, p67phox and p40phox accumulated on nascent phagosomes before the appearance of a PI3P probe, and in the presence of the PI3K inhibitor wortmannin, indicating that PI3P binding to p40phox is dispensable for the initial recruitment of p67phox and p40phox. Taken together, although confirming the importance of p40phox for phagocytosis-induced oxidant production, our results do not support a model in which PI3P-bound p40phox plays a significant role as a second carrier protein for p67phox to the phagosome, in addition to p47phox. Although a recent study in arachidonic acid–stimulated RAW 267.4 macrophage cells showed that PI3P-dependent binding of p40phox can mediate recruitment of p67phox to early endosomes,35 this setting is likely to have differences with phagocytic receptor–induced recruitment.

The current studies also reveal new insights into FcγR-induced p40phox recruitment to granulocyte phagosomes and the relative roles of its PI3P- and p67phox-binding domains. Simultaneous imaging of fluorescently tagged probes determined that full-length p40phox translocated to the phagosomal cup, whereas accumulation of the p40phox PX domain, a probe for PI3P, occurred 40 to 60 seconds after phagosome sealing, kinetics similar to PI3P probes in macrophages.18,19 Neither inhibition of PI3K by wortmannin nor an R105A mutation in p40phox that prevents PI3P binding eliminated recruitment of full-length p40phox to the phagosomal cup. However, a p40phox D289A mutation that disrupts its binding to p67phox almost completely abolished IgG-zymosan–induced translocation of p40phox in PLB-985 neutrophils, similar to the COSphox model.30 The importance of the PB1 domain for p40phox translocation in response to a physiologic signal extends results in a K562 cell model stimulated with either PMA or a muscarinic receptor50 and in a PMA-stimulated permeabilized human neutrophil system.34,37 Taken together, our data indicate that translocation of p40phox to both nascent and PI3P-rich internalized phagosomes is dependent on p67phox and does not initially require binding to PI3P. However, both wortmannin, and to an even greater extent, an R105A PI3P-binding mutant affected the persistence of p40phox on internalized phagosomes.

Our results support a model in which p40phox, p67phox, and p47phox, linked by separate high-affinity binding sites in p67phox for p47phox and for p40phox, translocate as a trimeric complex to the membrane-integrated flavocytochrome b after activation-induced unmasking of the p47phox-binding site for p22phox.2–4,37,52–55 This model is consistent with studies in CGD patients lacking either flavocytochrome b or p47phox showing that stable translocation of the trimeric phox complex requires interactions between p47phox and flavocytochrome b.10–12 For example, neither p67phox nor p40phox undergoes membrane translocation in p47phox-deficient CGD neutrophils, whereas p47phox translocation is unaffected in p67phox-deficient CGD.10–12 Taken together, these data suggest that p47phox is necessary and sufficient for stable recruitment of p67phox to the flavocytochrome b in phagosomal membranes, which in turn mediates that of p40phox.

A second implication from our results is that recruitment of cytosolic phox subunits of the NADPH oxidase complex to the phagosome is insufficient for high-level superoxide production, and the predominant role of PI3P binding by p40phox is to stimulate FcγR-induced superoxide production after enzyme assembly rather than to drive p67phox translocation. Whereas wild-type p40phox rescued phagocytosis-induced superoxide production in p40phox-deficient PLB-985 neutrophils phagosomes, the R105A PX domain mutant did not, confirming previous studies30,33 and extending these findings to show that an intact PI3P-binding domain is also required before sealing. This suggests that there may be small amounts of PI3P in the plasma membrane not detectable by imaging probes, as previously postulated,28,33 and that the marked increase in PI3P on internalized phagosomes may function to up-regulate oxidase activity in this sequestered compartment. In addition, since p40phoxR105A is present in phagosomal cup, these results further establish a role for this domain apart from one in translocation. That PI3P-bound p40phox has a direct effect on the assembled enzyme is supported by studies in semirecombinant systems in which p40phox stimulates superoxide production in the presence of PI3P,22,37 and where PI3P binding by the p40phox PX domain is required for oxidase activation but not for subunit translocation in vitro.34 Finally, a comparison of FcγR-induced oxidase activity in wortmannin-treated PLB-985 cells with cells expressing p40phoxR105A suggests that a substantial portion of the wortmannin effect both before and after internalization is mediated through inhibition of PI3P production, again confirming and extending a study in murine neutrophils expressing a PI3P-binding p40phox mutant.33

The R105A PX domain mutant of p40phox, which is unable to bind to PI3P, was recruited to nascent phagosomes but often disappeared within a few minutes after internalization. Why the PB1 domain–mediated interaction between p67phox and p40phox, which is necessary for p40phox translocation to the phagosome, appears insufficient to maintain p40phoxR105A after internalization is a paradox that will require further investigation. This observation also suggests that protein-protein interactions between oxidase subunits may be dynamic and are modified after assembly of the NADPH oxidase complex. In the resting state, the ability of the p40phox PX domain to access PI3P in the membrane is masked by an intramolecular interaction with the p40phox PB1 domain on the face opposite of the region that binds to p67phox.56 The mechanism that disrupts the intramolecular p40phox PX-PB1 interaction, leading to exposure of the PI3P-binding site, is unknown, although it does not appear to involve p40phox phosphorylation.35,56 It is possible that conformational changes in p40phox that accompany the unmasking of its PX domain or other events after phagosome internalization result in a requirement for PI3P binding in order for p40phox to be retained on phagosomes. A role for PI3P in p40phox retention after phagosome internalization may contribute to reduced NADPH oxidase activity in cells expressing a PI3P-binding mutant of p40phox.

In summary, this study demonstrates that membrane translocation of p40phox during FcγR-induced phagocyte NADPH oxidase assembly begins in the phagosomal cup and requires binding to p67phox. The data are consistent with a model in which p47phox functions as the key adaptor protein that is necessary and sufficient to recruit p67phox and p40phox to the membrane-bound flavocytochrome b. Although p40phox is not required to mediate assembly of the other cytosolic phox subunits on the phagosome, p40phox stimulates activity of the assembled NADPH oxidase complex via a PI3P signal that is spatially and temporally regulated to increase on internalized phagosomes. Future challenges include identifying underlying mechanisms by which the PX domain in p40phox becomes accessible to PI3P, how PI3P influences localization of p40phox after phagosome closure, and how p40phox stimulates activity of the NADPH oxidase complex. For example, it is possible that PI3P-bound p40phox induces conformational changes in other NADPH oxidase subunits, or acts to tether the oxidase complex to an optimal membrane microdomain, as recent studies in a cell-free model system suggest that the membrane phospholipid environment can have a large influence on the activity of the assembled oxidase complex.57

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

Presented in abstract form at the 48th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Hematology, Orlando, FL, December 11, 2006.58

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Georges Marchal for construction of retroviral vectors for expression of YFP-tagged p67phox, Christophe Marchal for assistance with analyzing p40phox-shRNA–transduced PLB-985 clones, and Shari Upchurch and Melody Warman for assistance with paper preparation.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD) grants R01 HL45635 (M.C.D. and S.J.A.) and GM52981 (M.B.Y.), the Indiana University Cancer Center Flow Cytometry and Imaging Cores P30 CA082709, the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (Canadian IHR, Ottawa, ON; S.G.), and the Riley Children's Foundation (Indianapolis, IN; M.C.D.). Microscope facilities in the Indiana Center for Biological Microscopy are also supported by a grant (INGEN) from the Lilly Endowment (Indianapolis, IN).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: W.T. and X.J.L. designed, performed, and analyzed experiments, prepared the figures, and helped draft the paper; W.M. and N.D.S. performed and analyzed experiments; C.-I.S. prepared critical reagents; S.A.B. and M.B.Y. provided a critical reagent; S.G. helped with interpretation of data and paper preparation; S.J.A. and M.B.Y. analyzed and interpreted data and helped with paper preparation; and M.C.D. oversaw this entire project including the experimental design, analysis, interpretation of the data, and preparation of the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Mary C. Dinauer, Cancer Research Institute, R4 402C, Indiana University School of Medicine, 1044 W Walnut Street, Indianapolis, IN 46202; e-mail: mdinauer@iupui.edu.

References

Author notes

*W.T. and X.J.L. contributed equally to this work.