Abstract

Venous thromboembolism is a major medical problem, annually affecting 1 in 1000 individuals. It is a typical multifactorial disease, involving both genetic and circumstantial risk factors that affect a delicate balance between procoagulant and anticoagulant forces. In the last 50 years, the molecular basis of blood coagulation and the anticoagulant systems that control it have been elucidated. This has laid the foundation for discoveries of both common and rare genetic traits that tip the natural balance in favor of coagulation, with a resulting lifelong increased risk of venous thrombosis. Multiple mutations in the genes for anticoagulant proteins such as antithrombin, protein C, and protein S have been identified and constitute important risk factors. Two single mutations in the genes for coagulation factor V (FV Leiden) and prothrombin (20210G>A), resulting from approximately 20 000-year-old mutations with subsequent founder effects, are common in the general population and constitute major genetic risk factors for thrombosis. In celebration of the 50-year anniversary of the American Society of Hematology, this invited review highlights discoveries that have contributed to our present understanding of the systems that control blood coagulation and the genetic factors that are involved in the pathogenesis of venous thrombosis.

Introduction

Venous thromboembolism is a major medical problem, affecting 1 in 1000 individuals annually, and most physicians come in contact with patients suffering from the disease regardless of their clinical specialty. It is a typical multifactorial disease, the pathogenesis involving both circumstantial and genetic mechanisms. As early as 1856, Virchow discussed 3 broad categories of factors contributing to venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, including alterations in the blood flow, changes in the constitution of blood, and changes in the vessel wall.1 This is known as Virchow's triad and is still a useful concept to illustrate the pathogenesis of thrombosis. Our present understanding of the mechanisms of the disease reinforces this concept, with known genetic and circumstantial risk factors affecting one or more of the 3 categories of Virchow's triad. Circumstantial factors that increase the risk of thrombosis include increasing age, immobilization, surgery, pregnancy, oral contraceptives, hormone replacement, and inflammatory conditions. Essentially all veins are vulnerable to thrombosis, although most common is thrombosis in the lower limbs. This is due to high hydrostatic pressure and the low flow rate that affect the veins in the legs, in particular when the vessel wall elasticity decreases with age and the venous valves become insufficient

In the past 50 years, the molecular basis of both blood coagulation and the anticoagulant pathways has been elucidated, and several genetic risk factors for venous thrombosis have been identified. These genetic risk factors affect the natural anticoagulant mechanisms and result in a hypercoagulable state due to an imbalance between procoagulant and anticoagulant forces. The increased risk of thrombosis is lifelong, and thrombotic events tend to occur when one or more of the circumstantial risk factors come into play. The present review will provide a historical perspective of venous thrombosis research, highlighting the discoveries that have contributed most to our understanding of the anticoagulant systems and lead to the identification of genetic risk factors for thrombosis.

Multiple anticoagulant mechanisms control blood coagulation

At sites of vascular injury, activation of blood coagulation results in the generation of high concentrations of thrombin that activate platelets and coagulate blood (Figure 1). The efficient coagulation system is controlled by several anticoagulant mechanisms, ensuring that the clotting process remains a local process. The initiation of the coagulation system is the result of exposure of tissue factor (TF) to blood and the subsequent binding and activation of factor VII (FVII).2-5 TF serves as a cofactor to the enzyme FVIIa, the TF-FVIIa complex efficiently activating factor IX (FIX) and factor X (FX). The ensuing reactions take place on the surface of negatively charged phospholipid membranes, exposed on activated platelets, onto which the blood coagulation proteins bind and assemble into enzymatically active complexes. Thus, FIXa binds to its cofactor FVIIIa forming the tenase (FIXa-FVIIIa) complex that activates additional FX, whereas FXa together with FVa form the prothrombinase (FXa-FVa) complex that efficiently converts prothrombin (PT) to thrombin. In these membrane-bound complexes, FVIIIa and FVa serve as important cofactors to the enzymes FIXa and FXa, respectively. Indeed, without the cofactors and the negatively charged phospholipid, the efficiency of the 2 enzymes FIXa and FXa is negligible, further ensuring that the enzymatic reactions remain localized. The generated thrombin positively feedback-activates the coagulation system by converting circulating precursors FVIII and FV into their active forms. The whole system is designed to provide massive amplification of an initiating stimulus and if not appropriately controlled, it would rapidly convert circulating blood into a clot.

The initiation and propagation of blood coagulation. The reactions of blood coagulation take place on the surface of cell membranes where enzymes and cofactors form complexes that efficiently convert their respective proenzyme substrates to active enzymes. The reaction sequence is initiated by the exposure of tissue factor (TF) to blood with subsequent binding of FVII/FVIIa and activation of FIX and FX. The following assembly of tenase (FIXa/FVIIIa) and prothrombinase (FXa/FVa) complexes on the surface of negatively charged phospholipid membranes (provided mainly by platelets) results in amplification, propagation, and generation of high concentrations of thrombin (T). The initial thrombin that is formed feedback-activates FVIII (circulating with von Willebrand factor [VWF]) and FV. Illustration by Marie Dauenheimer.

The initiation and propagation of blood coagulation. The reactions of blood coagulation take place on the surface of cell membranes where enzymes and cofactors form complexes that efficiently convert their respective proenzyme substrates to active enzymes. The reaction sequence is initiated by the exposure of tissue factor (TF) to blood with subsequent binding of FVII/FVIIa and activation of FIX and FX. The following assembly of tenase (FIXa/FVIIIa) and prothrombinase (FXa/FVa) complexes on the surface of negatively charged phospholipid membranes (provided mainly by platelets) results in amplification, propagation, and generation of high concentrations of thrombin (T). The initial thrombin that is formed feedback-activates FVIII (circulating with von Willebrand factor [VWF]) and FV. Illustration by Marie Dauenheimer.

Control of blood coagulation is achieved by several anticoagulant mechanisms and at all levels of the system. Tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) regulates the very initiation of coagulation. It binds and inhibits newly formed FXa that is associated with the TF-FVIIa complex.4,6,7 The activated coagulation enzymes can all be inhibited by the circulating serine protease inhibitor (serpin) antithrombin (AT), in particular when the enzymes are not engaged with their respective cofactors.4,8 Another mechanism of control is achieved by regulation of the 2 cofactors FVIIIa and FVa by the protein C (PC) anticoagulant system. Most genetic defects associated with thrombophilia have been found to affect this system,4,6,9-11 and its discovery and associated defects will be the major focus of this presentation. First, however, is a brief discussion about antithrombin deficiency as a cause of thrombophilia.

Antithrombin deficiency, the first identified genetic risk factor for venous thrombosis

As early as 1905, Morawitz proposed the concept of antithrombin (AT) being responsible for the loss of thrombin activity after coagulation of blood but it took until 1963 before an assay for AT in plasma from clinical patients was presented.12 Shortly thereafter in 1965, Egeberg reported the presence of AT deficiency in a family having many members suffering from venous thrombosis.13 AT is a multifunctional serpin, inhibiting essentially all the active enzymes of the coagulation pathway.8 By itself, AT is a slow inhibitor, but the heparan sulfate (HS) family of glycosaminoglycans present on intact endothelium stimulates its inhibitory activity.14 In vivo, this provides the basis for localization of the inhibitory activity of AT to the surface of endothelial cells. Heparin, which is a member of the HS family, is a particularly efficient stimulator of AT activity and has been used as an anticoagulant drug for more than 70 years. The AT-binding region in heparin has been localized to a pentasaccharide sequence.15 This knowledge has been the basis for development of new synthetic pentasaccharide drugs containing this sequence that stimulate the anticoagulant activity of AT.

No case of type I homozygous AT deficiency has been described, suggesting that complete AT deficiency is incompatible with life. This is further supported by the lethal phenotype observed in AT knockout mice.16 There have been several type II homozygotes described with mutations in the heparin-binding region of AT. Heterozygous type I AT deficiency is relatively rare in the general population (approximately 1 in 2000) and it is associated with an approximately 10-fold increased risk of thrombosis. It is present in 1% to 2% of patients of thrombosis cohorts. A large number of different mutations (missense, nonsense, and deletions) in the AT gene have been described, resulting either in functional defects or low plasma levels.8,17

Elucidation of the protein C anticoagulant pathway

Many of the proteins of blood coagulation are vitamin K dependent, and vitamin K antagonists (eg, dicoumarol or warfarin) have been used to treat thrombosis since the 1950s. The description in 1974 of the posttranslationally modified γ-carboxyglutamic acid (Gla), uniquely present in vitamin K–dependent proteins, was not only a breakthrough for the understanding of blood coagulation mechanisms, but also paved the way for the discovery of a vitamin K–dependent anticoagulant pathway we now know as the protein C pathway.18-20 Protein C was isolated and identified as a vitamin K–dependent protein by Stenflo in 197621 and was soon shown to have anticoagulant properties after its activation by thrombin.22,23 The rapid elucidation of the function of protein C was facilitated by the realization that activated protein C (APC) was identical to autoprothrombin IIa, an anticoagulant activity described in the 1960s by Seegers et al in Detroit.24 Autoprothrombin IIa activity was generated after thrombin treatment of a prothrombin pre-paration, which in retrospect would certainly have contained protein C, although at the time it was believed to be a fragment of prothrombin. However, Marciniak did subsequently report in 1972 that the precursor of autoprothrombin IIa was a protein distinct from prothrombin.25

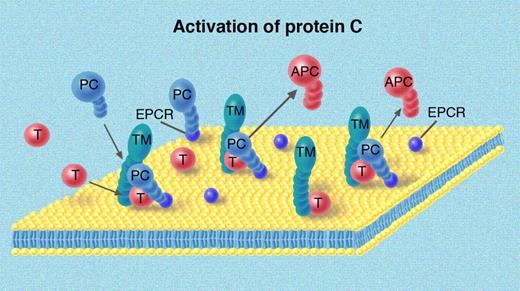

Thrombin itself is a poor activator of protein C, and the discovery by Owen and Esmon in 198126 of thrombomodulin (TM) as a cofactor for the reaction was crucially important for the understanding of the system.10,27 TM is present on the surface of endothelial cells and thrombin that is generated in the vicinity of intact endothelium binds with high affinity to TM. This is associated with loss of the procoagulant activities of thrombin and gain of the ability to activate protein C (Figure 2). The highest concentration of TM in the circulation is in the capillary bed, where the surface to volume ratio reaches its maximum. The high TM concentration of TM in the microcirculation is crucial for local protein C activation and anticoagulation of blood. In recent years, an endothelial cell protein C receptor (EPCR) has been identified and found to be important for the activation of protein C.28 EPCR binds to the Gla domain of protein C and helps present the protein C for the activating T-TM complex. The generated APC has a relatively long half-life in the circulation (approximately 20 minutes) and is slowly inhibited by either the protein C inhibitor (PCI) or by α-1 antitrypsin. APC inhibits the coagulation pathway by specifically cleaving a limited number of peptide bonds in FVIIIa and FVa, 2 of the important cofactors of the coagulation pathway.9-11,29,30

Activation of protein C by thrombin-thrombomodulin. Thrombomodulin (TM) is present on all endothelial cells and serves as a cofactor to thrombin in the activation of protein C. The endothelium also contains the endothelial protein C receptor (EPCR) that binds the Gla domain of protein C and helps present protein C to the T/TM complex. The activated protein C (APC) then floats along with the bloodstream to control reactions of coagulation. Illustration by Marie Dauenheimer.

Activation of protein C by thrombin-thrombomodulin. Thrombomodulin (TM) is present on all endothelial cells and serves as a cofactor to thrombin in the activation of protein C. The endothelium also contains the endothelial protein C receptor (EPCR) that binds the Gla domain of protein C and helps present protein C to the T/TM complex. The activated protein C (APC) then floats along with the bloodstream to control reactions of coagulation. Illustration by Marie Dauenheimer.

Soon after the report on protein C, DiScipio, a PhD student in Davie's laboratory in Seattle, discovered yet another vitamin K–dependent protein, which was named protein S (DiScipio et al31 ). A few years later, Walker showed that protein S functions as a cofactor to APC.32 Another interesting feature of protein S that was soon discovered is that the protein is present in 2 forms in plasma, as free protein S (30%-40%) and as part of a complex with the complement regulator C4b-binding protein (C4BP).33 The major isoform of C4BP in plasma is composed of 7 identical α-chains, each containing a binding site for the complement protein C4b, and a single protein S binding β-chain, the chains being arranged in an octopus-like fashion.34 Free protein S serves as an APC cofactor, whereas bound protein S can localize C4BP to negatively charged phospholipid membranes (eg, those exposed on the surface of apoptotic cells), thus providing local control of complement system activation.34

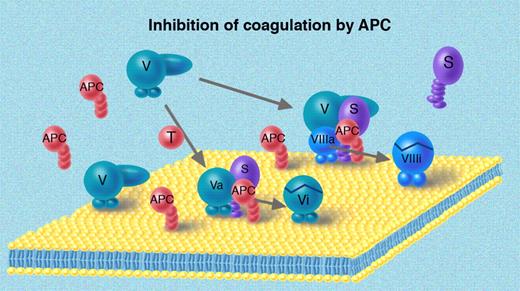

The APC-mediated inhibition of FVIIIa and FVa occurs on the surface of negatively charged phospholipid membranes (Figure 3). Intrinsically, FVIIIa and FVa are both highly sensitive to APC, but in the assembled tenase and prothrombinase complexes, they are partially protected because their respective enzyme, FIXa and FXa, sterically hinders APC. There are several APC-sensitive sites in both FVIIIa (R336 and R562) and FVa (R306, R506, and R679), and cleavage by APC results in loss of binding sites for the enzymes FIXa and FXa, respectively, dissociation of fragments, and disintegration of the FVIIIa and FVa molecules.29,30,35,36 The activity of APC is stimulated by protein S, the 2 vitamin K–dependent proteins forming a complex on the negatively charged phospholipid surface. In the regulation of the tenase complex by APC, the APC-cofactor activity of protein S is synergistically stimulated by the intact form of FV, suggesting that FV has the potential to express both procoagulant and anticoagulant properties.30,37 The plasma concentration of FVIII is almost 2 orders of magnitude lower than that of FV. As a consequence, during activation of coagulation, tenase complexes are scarce in comparison with the abundant prothrombinase complexes. This may explain the need for the 2 APC-cofactors—protein S and FV—for the regulation of tenase, whereas one cofactor—protein S—suffices in the regulation of prothrombinase complexes (Figure 4).

Degradation of FVa and FVIIIa by APC. Both FVa and FVIIIa are cleaved and inhibited by APC in surface-bound reactions also involving cofactors to APC. Protein S and APC interact on the membrane and are sufficient to inhibit FVa, whereas the regulation of the FVIIIa additionally involves FV, which in this situation serves as cofactor to APC. Illustration by Marie Dauenheimer.

Degradation of FVa and FVIIIa by APC. Both FVa and FVIIIa are cleaved and inhibited by APC in surface-bound reactions also involving cofactors to APC. Protein S and APC interact on the membrane and are sufficient to inhibit FVa, whereas the regulation of the FVIIIa additionally involves FV, which in this situation serves as cofactor to APC. Illustration by Marie Dauenheimer.

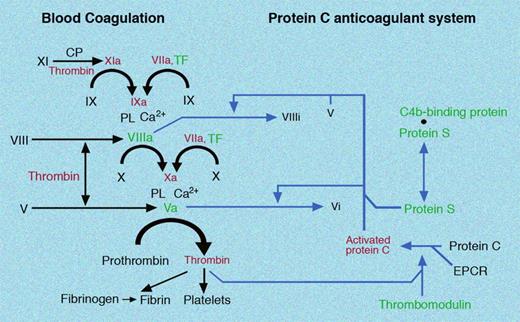

Schematic representation of blood coagulation and the protein C anticoagulant system. The reactions that are presented in Figures 1 to 3 are here summarized in a schematic form. In addition to the FVIIa/TF-triggered initiation of coagulation, the scheme indicates the activation of FXI by either the contact phase system (CP) or by thrombin. The figure also highlights the dual role of thrombin as both a procoagulant and anticoagulant factor. Illustration by Marie Dauenheimer.

Schematic representation of blood coagulation and the protein C anticoagulant system. The reactions that are presented in Figures 1 to 3 are here summarized in a schematic form. In addition to the FVIIa/TF-triggered initiation of coagulation, the scheme indicates the activation of FXI by either the contact phase system (CP) or by thrombin. The figure also highlights the dual role of thrombin as both a procoagulant and anticoagulant factor. Illustration by Marie Dauenheimer.

Identification of protein C deficiency in patients with thrombosis

The discovery of the anticoagulant activity of APC called for determination of the protein C concentration in thrombosis patients. In 1981, Griffin et al were the first to describe heterozygous protein C deficiency in a family with a history of recurring thrombosis.38 A few years later, homozygous protein C deficiency was found to be associated with severe neonatal purpura fulminans due to extensive intravascular thrombotization of the microvasculature.39 Since then, a large number of protein C deficiencies (type I or type II) have been described and their genetic background elucidated.40 Type I deficiency denotes cases with decreased protein concentration, whereas cases with type II deficiency have normal protein C concentration but low protein C activity. In cohorts of thrombosis patients, protein C deficiency was found slightly more often than AT deficiency, but still in less than 5% of the patients.41-44 It was initially believed that protein C deficiency was a strong risk factor for thrombosis and protein C deficiency was expected to be rare in the general population. Therefore, it was surprising when Miletich et al in 1987 reported protein C deficiency to be rather common among blood donors—prevalence approximately 1:250—and that thrombosis was uncommon in these individuals and their family members with protein C deficiency.45 The subsequent identification of identical protein C gene mutations in thrombosis-prone families and in families with low incidence of thrombosis was particularly puzzling at the time. A new idea emerged based on these observations, suggesting protein C deficiency in itself to be a relatively mild risk factor and that the thrombosis-prone protein C–deficient families carried additional genetic factors that increased the risk of thrombosis.46 This concept was soon to gain additional support by the discovery of APC resistance as a risk factor for thrombosis, and of the common FV gene mutation that causes the condition.

Identification of protein S deficiency in patients with thrombosis

In 1984, the first thrombosis patients with protein S deficiency were described by Comp and Esmon,47 Comp et al,48 and Schwarz et al.49 Comp and Esmon observed that in some patients only the free form of protein S was low, whereas the C4BP-bound protein S (and total protein S) was normal. This pattern has been referred to as type III protein S deficiency. In other cases, both the free and total protein S levels were low (type I). Functional deficiency of protein S (type II) has been described in only few cases, presumably due to the lack of reliable functional assays for protein S. The difference between types I and III was for many years elusive, but extensive family studies performed in the 1990s demonstrated that certain families had both types associated with the same mutation suggesting that the 2 types are phenotypic variants of the same protein S gene defects.50 The molecular explanation for the 2 types was provided by careful analysis of the molar concentrations of protein S and the β-chain containing C4BP (C4BPβ+) in plasma.51 Under normal conditions, the concentration of protein S exceeds that of C4BPβ+ by approximately 30% to 40%. The 2 proteins bind to each other with very high affinity and as a result, the free protein S is the molar surplus of protein S over the C4BPβ+. Mild protein S deficiency will consequently present with selective deficiency of free protein S, whereas more pronounced protein S deficiency will also decrease the complexed protein S and consequently the total protein S level.50,52,53 These data explain why assays for free protein S have higher predictive value for protein S deficiency.

Discovery of APC resistance/FV Leiden as a major risk factor for venous thrombosis

In studies of thrombosis cohorts performed during the 1980s, deficiencies of AT, protein C, and protein S were identified in less than 10% of the patients even though positive family histories were present in up to 40% of the cases.41,42,44 This suggested that there were more genetic risk factors to be identified, and in 1993 a breakthrough came in my laboratory with the discovery of APC resistance.54 As many times in the history of science, serendipity was involved. An unexpected behavior in a functional assay for protein C of a single plasma sample from a patient with thrombosis was the starting point for the search of the underlying mechanism.55,56 An early key observation was that the addition of APC to the patient plasma in a clotting assay did not result in the expected prolongation of clotting time. This phenomenon prompted me to coin the term APC resistance as a phenotypic description of the condition. Follow-up work demonstrated that APC resistance was inherited, in the original patient's family as well as in other investigated thrombosis-prone families.54 In subsequent studies of thrombosis cohorts, APC resistance was found to be highly prevalent (20%-60%) among thrombosis patients and also to be relatively common in healthy control populations (5%-10%).57-59 Moreover, plasma-mixing experiments demonstrated that the underlying mechanism of APC resistance was the same in all identified APC-resistant individuals.59

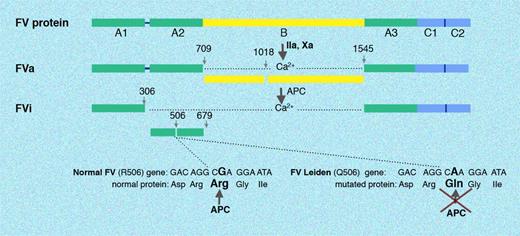

A protein extract of normal plasma was found to be able to normalize the APC resistance, which provided a means to identify and purify the protein involved in the molecular mechanism of APC resistance. The protein was purified in my laboratory, and in early 1994 we reported that its identity was coagulation factor V, suggesting APC resistance to be caused by a mutation in the FV gene.60 Soon several laboratories independently reported finding the same causative mutation in the FV gene, a single point mutation that results in the replacement of Arg506 in one of the APC-cleavage sites with a Gln (Figure 5).61-65 The mutant FV is commonly referred to as FV Leiden, as Bertina et al61 from the Dutch city of Leiden were the first to report the mutation. Unexpectedly, the FV mutation results in impaired degradation not only of FVa but also of FVIIIa, the explanation being that the APC-cofactor activity of intact FV in the regulation of the tenase complex is dependent on cleavage at Arg506 by APC.37,66-68 The intricate details of the molecular effects of the FV Leiden mutation are described elsewhere, as is the full story of the discovery of APC resistance.30,55,56,69

Activation and degradation of normal FV and FV Leiden. FV circulates as a single-chain high-molecular-weight protein. Thrombin (or FXa) cleaves a number of peptide bonds, which results in the liberation of the B domain and generation of FVa. Three peptide bonds in FVa are cleaved by APC (Arg306, Arg506, and Arg679) resulting in inhibition of FVa activity. The FV Leiden mutation eliminates one of the APC cleavage sites, which impairs the degradation of FVa. Illustration by Marie Dauenheimer.

Activation and degradation of normal FV and FV Leiden. FV circulates as a single-chain high-molecular-weight protein. Thrombin (or FXa) cleaves a number of peptide bonds, which results in the liberation of the B domain and generation of FVa. Three peptide bonds in FVa are cleaved by APC (Arg306, Arg506, and Arg679) resulting in inhibition of FVa activity. The FV Leiden mutation eliminates one of the APC cleavage sites, which impairs the degradation of FVa. Illustration by Marie Dauenheimer.

The prevalence of FV Leiden in different populations varies widely from being absent to being found in up to 15% of healthy individuals.30,70 All individuals with FV Leiden share the same FV gene haplotype, suggesting a founder effect. Zivelin et al estimated the mutation to be approximately 21 000 years old.71 This therefore occurred after the “Out of Africa Exodus” and the subsequent separation of the human races, explaining why the FV mutation is found among whites, while it is rare or absent in populations from Far East Asia, in black Africans, as well as in indigenous populations of America and Australia. It is believed that the absence of the FV Leiden mutation among these populations is the explanation for their lower incidence of thrombosis. In Europe, the mutation is particularly common (up to 15%) in certain areas (eg, southern Sweden, Germany, and Cyprus).30,70 Similar high numbers have been found in many Middle Eastern countries. In other regions, such as in Italy and Spain, the mutation is less frequent. In multicultural societies, the ethnic background of the population determines the prevalence of FV Leiden.

Heterozygosity for FV Leiden yields a lifelong hypercoagulable state associated with approximately 5-fold increased risk of venous thrombosis, the risk being considerably higher (approximately 50-fold) among homozygotes.72-74 The most common clinical manifestations are venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, whereas the FV Leiden mutation is not a risk factor of arterial thrombosis.75,76 The high prevalence in certain populations suggests that the FV mutation has provided a survival advantage. It has been shown that the FV Leiden mutation confers a lower risk of severe bleeding after delivery, which during the history of humankind should have provided a major survival benefit.77 On the other hand, the increased risk of venous thrombosis associated with FV Leiden has presumably not been a strong negative survival factor because thrombosis occurs relatively late in life and does not affect fertility.

Identification of a prothrombin mutation as risk factor for venous thrombosis

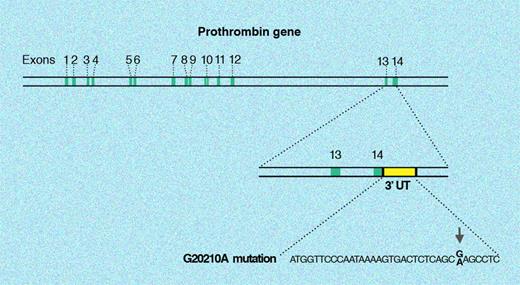

A few years after the identification of APC resistance and the causative FV Leiden mutation, Poort et al in Leiden identified yet another single point mutation as a risk factor of venous thrombosis.78 In this case, the successful identification of the mutation was based on a candidate gene approach involving extensive sequencing of certain genes in thrombosis patients and controls. The mutation is located in the 3′ untranslated region of the prothrombin gene (nucleotide 20210 G to A) and thus does not change the structure of the prothrombin molecule (Figure 6). However, the mutation is associated with slightly increased plasma levels of prothrombin, which results in a hypercoagulable state and a lifelong 3- to 4-fold increased risk of venous thrombosis.74 Like the FV Leiden mutation, a founder effect has been established (the mutation is approximately 24 000 years old), and the prevalence of the prothrombin mutation varies dependent on the geographic location and ethnic background.71 The mutation is found in 2% to 4% of healthy individuals in southern Europe, which is twice as high as that in northern Europe. Like FV Leiden, it is rare in Far East Asian populations, in Africa, and in indigenous populations of Australia and the Americas. In Western societies today, the mutation is found in 6% to 8% of venous thrombosis patients.79

20210G>A mutation in the prothrombin gene. The single point G to A mutation at position 20210 affects the 3′ untranslated region of the prothrombin gene (F2). Thus the protein-coding sequence of the prothrombin gene is not affected by this mutation. Illustration by Marie Dauenheimer.

20210G>A mutation in the prothrombin gene. The single point G to A mutation at position 20210 affects the 3′ untranslated region of the prothrombin gene (F2). Thus the protein-coding sequence of the prothrombin gene is not affected by this mutation. Illustration by Marie Dauenheimer.

Thrombophilia is a multifactorial disease

The pathogenesis of venous thromboembolism involves environmental and genetic risk factors, and venous thromboembolism has emerged as a typical example of a multifactorial disease.73,80-83 In societies where the FV Leiden and prothrombin 20210A alleles are common, many individuals are expected to carry more than one genetic risk factor. In contrast, in countries having low FV Leiden and prothrombin 20210A allele frequencies, few individuals will carry multiple genetic defects. This may explain the lower incidence of thromboembolic disease in, for example, China and Japan compared with Europe and the United States. The number of individuals carrying 2 or more genetic defects can be calculated on the basis of the prevalence of the genetic defects in the population. Assuming a prevalence of FV Leiden of 10%, combinations of protein C or protein S deficiency and FV Leiden are expected to be present in between 1 to 3 per 10 000 individuals, whereas the combination of prothrombin and FV mutations would be found in 1 to 2 per 1000 individuals. Thus, quite a substantial number of people would belong to the high-risk group with more than one genetic defect.74,84,85

The incidence of thrombosis in individuals having genetic defects is highly variable and some individuals never develop thrombosis, whereas others develop recurrent severe thrombotic events at an early age. This depends on the particular genotype, the coexistence of other genetic defects, and the influence of environmental risk factors such as oral contraceptives, trauma, surgery, and pregnancy. Thus, women with heterozygosity for the FV Leiden allele who also use oral contraceptives have been estimated to have a 35- to 50-fold increased risk of thrombosis, while those with homozygosity have a several hundred–fold increased risk.86

Laboratory evaluation of genetic risk factors for thrombosis

FV Leiden can be identified by DNA-based assays or by functional APC-resistance tests having close to 100% sensitivity and specificity for the FV mutation.87,88 To distinguish heterozygosity and homozygosity, DNA tests are required. Pseudohomozygous FV Leiden (ie, individuals with one mutant FV allele and one null allele) is suspected when the APC resistance test indicates a more severe phenotype than the DNA test. Thus, even though the DNA test suggests heterozygosity, in plasma all FV molecules are APC resistant because the null allele is not expressed. DNA tests are required to identify the prothrombin mutation (20210G>A), whereas protein C, protein S, or AT is assayed by functional or immunologic tests.88 Assays for the free form of protein S are preferred over those measuring the total protein S level as they have higher predictive value for protein S deficiency.50,52 Many different mutations in the genes for protein C, protein S, and AT have been have been found and DNA-based tests are not at present considered useful for initial screening of thrombosis patients.

Management of thrombophilia

Venous thrombosis is in most cases initially treated with a combination of heparin and vitamin K antagonists.89-94 The heparin can be either unfractionated (UFH) or low molecular weight (LMWH), prepared from UFH by either enzymatic or chemical cleavage methods. LMWH has better pharmacokinetic properties than UFH, and adequate anticoagulant control can be achieved with a twice daily or single daily dose given subcutaneously. Heparin is discontinued after a few days when the functional levels of vitamin K–dependent coagulation proteins have dropped into the therapeutic range. The effect of vitamin K antagonist therapy should be regularly monitored by prothrombin time–international normalized ratio (PT-INR) and it is usually continued for 3 to 6 months depending on the severity of the thrombosis and its cause. The benefits of the anticoagulation effect must always be weighed against the risk of bleeding complications. Patients with one genetic risk factor should be managed in the same way as any other patient with thrombotic events until more specific recommendations are established. It is not yet established whether the presence of a single genetic defect is associated with an increased risk of recurrence. Among patients with unprovoked VTE, most studies indicate that the presence of heterozygous factor V Leiden alone does not lead to a higher recurrence rate than among those without an identifiable mutation. Patients with combined genetic risk factors may be at increased risk of recurrence, and accordingly long-term anticoagulation therapy beyond 6 months may be considered, even after an isolated thromboembolic event. However, more data are needed before these recommendations can be considered generally applicable.93 In years to come, alternative anticoagulant drugs (eg, synthetic pentasaccarides as an alternative to LMWH or oral direct inhibitors of thrombin, FXa, or FVIIa) will possibly replace the currently used therapeutic strategies95-97 and hopefully decrease the risk of bleeding complications and diminish the need of frequent monitoring. To date, there are no generally accepted recommendations regarding screening for FV Leiden prior to oral contraceptive use, pregnancy, and surgery. More prospective data are needed, not least in terms of cost-benefit ratios in populations with different prevalence of the mutation, before any general recommendations can be made.

Genetic risk factors for thrombophilia yet to be discovered?

It is noteworthy that it has been more than 10 years since the prothrombin 20210G>A mutation was discovered, and one might wonder whether there are many more additional genetic risk factors of thrombosis yet to be discovered. In this respect, it is interesting to compare thrombophilia with another multifactorial disease such as type 2 diabetes, which until recently was considered a geneticist's nightmare.98 During the last few years, major advances have been made in the understanding of the genetics of type 2 diabetes, with the identification of 11 gene regions being involved. The breakthrough depended on the availability of new high-throughput genome-wide DNA analysis of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of large well-defined patient cohorts.98 It is striking that all the newly identified genetic risk factors have considerably lower odds ratios (less than 1.5) than all the known risk factors of thrombophilia. A similar high-throughput approach, applied to well-defined cohorts of patients with venous thrombosis, could help identify common genetic risk factors for thrombosis with low individual odds ratios. Novel DNA technologies, together with candidate gene approaches, studies of thrombophilic families, and a more detailed investigation of key biologic pathways, will hopefully further deepen our understanding of venous thromboembolism and result in improved preventive measures and new therapeutic targets.

Authorship

Contribution: B.D. wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: B.D. is patent holder for APC resistance and free protein S assays and receives royalties from Instrumentation Laboratory on the sale of such assays. B.D. is also a member of the scientific advisory committee of Instrumentation Laboratory.

Correspondence: Björn Dahlbäck, Department of Laboratory Medicine, Section of Clinical Chemistry, Lund University, University Hospital Malmö, SE 20502 Malmö, Sweden; e-mail: bjorn.dahlback@med.lu.se.

![Figure 1. The initiation and propagation of blood coagulation. The reactions of blood coagulation take place on the surface of cell membranes where enzymes and cofactors form complexes that efficiently convert their respective proenzyme substrates to active enzymes. The reaction sequence is initiated by the exposure of tissue factor (TF) to blood with subsequent binding of FVII/FVIIa and activation of FIX and FX. The following assembly of tenase (FIXa/FVIIIa) and prothrombinase (FXa/FVa) complexes on the surface of negatively charged phospholipid membranes (provided mainly by platelets) results in amplification, propagation, and generation of high concentrations of thrombin (T). The initial thrombin that is formed feedback-activates FVIII (circulating with von Willebrand factor [VWF]) and FV. Illustration by Marie Dauenheimer.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/112/1/10.1182_blood-2008-01-077909/4/m_zh80100819500001.jpeg?Expires=1767736295&Signature=BjFJZm4mCIgSe2sHYoq-UoktO6JLpt3aZq3zN1Ajzp4SQ6R0iPphXDgdiwtfGeJCSBt8pDfJvLL~GQr2BxdDCTfbL1OXt7pWjDGHwD~3gpprcfwUP61SQCjvNEKW~TGz76u3wz0moJSqtF0E0tz6oBnc6MEZgjukd5gjEGu~HyxKIr9KFp5tZ980h7pb4RHbwhhbuleWd0mqIIsu79DGfvvgnbcDr201-B16gesHrQHseSGWm0E~gOOLR0a3liGZQm4FH3cG0r8oqIKB8YgXwRZ8vshRKBANG89AkZVloYvn~ygQlXfWCMrRsXYLbJD-MMQKjJFixV67nzh-XxrFOA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal