Hepatic stellate cells are believed to play a key role in the development of liver fibrosis. Several studies have reported that bone marrow cells can give rise to hepatic stellate cells. We hypothesized that hepatic stellate cells are derived from hematopoietic stem cells. To test this hypothesis, we generated chimeric mice by transplantation of clonal populations of cells derived from single enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)–marked Lin−Sca-1+c-kit+CD34− cells and examined the histology of liver tissues obtained from the chimeric mice with carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)–induced injury. After 12 weeks of CCl4 treatment, we detected EGFP+ cells in the liver, and some cells contained intracytoplasmic lipid droplets. Immunofluorescence analysis demonstrated that 50% to 60% of the EGFP+ cells were negative for CD45 and positive for vimentin, glial fibrillary acidic protein, ADAMTS13, and α-smooth muscle actin. Moreover, EGFP+ cells isolated from the liver synthesized collagen I in culture. These phenotypes were consistent with those of hepatic stellate cells. The hematopoietic stem cell–derived hepatic stellate cells seen in male-to-male transplants revealed only one Y chromosome. Our findings suggest that hematopoietic stem cells contribute to the generation of hepatic stellate cells after liver injury and that the process does not involve cell fusion.

Introduction

Hepatic stellate cells reside within the perisinusoidal space of Disse beneath the endothelial barrier and undergo a gradual transition from a quiescent, vitamin A–storing phenotype to an activated myofibroblast-like phenotype after liver injury.1,,,–5 These activated stellate cells synthesize large amounts of extracellular matrix proteins, such as collagens I, III, IV, V, and VI, fibronectin, laminin, and proteoglycans, during liver fibrogenesis.6,–8 Hepatic stellate cells have long cytoplasmic processes that run parallel to the sinusoidal endothelial wall, make contact with numerous hepatocytes, and function as liver-specific pericytes.4,9,10 As hepatic stellate cells contract and relax in response to various vasoactive mediators, they may play a role in the regulation of sinusoidal tone and blood flow in normal liver.10,11 Accordingly, hepatic stellate cells are associated with liver fibrosis and portal hypertension. However, the exact nature and origin of hepatic stellate cells have not been fully elucidated, despite the pathophysiologic implications

Hepatic stellate cells express mesenchymal markers, such as vimentin, desmin, and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), or neural/neuroectodermal markers, such as glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), neural cell adhesion molecule, and synaptophysin.2,5,12,,,–16 Based on these characteristic phenotypes, the embryonic origin of hepatic stellate cells is thought to be the septum transversum mesenchyme or neural crest.2,17,18 Cassiman et al19 reported that hepatic stellate cells do not descend from the neural crest in transgenic mice expressing yellow fluorescent protein in all neural crest cells and their derivatives, and they may derive from the septum transversum mesenchyme, endoderm, or the mesothelial liver capsule. On the other hand, the origin of hepatic stellate cells in the adult liver has remained obscure.

Recently, some investigators have demonstrated that crude bone marrow (BM) cells can populate the hepatic stellate cells of lethally irradiated mice.20,21 Because adult BM contains both hematopoietic stem cells and mesenchymal stem cells, it is unclear which type of stem cell truly contributes to hepatic stellate cells. Previous reports revealed that glomerular mesangial cells in kidney and perivascular pericyte-like cells in brain are derived from hematopoietic stem cells in mice that received single hematopoietic stem-cell transplants.22,23 Interestingly, both cell types are considered to belong to the myofibroblast family. More recently, it has also been reported that fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in many organs and tissues originate from hematopoietic stem cells.24 From the observation that myofibroblasts are of hematopoietic stem-cell origin and the notion that the quiescent hepatic stellate cells switch to activated myofibroblast-like cells in association with inflammation, we hypothesized that hepatic stellate cells may also be derived from hematopoietic stem cells.

To test our hypothesis, we generated chimeric mice by transplantation of clonal populations of cells derived from single lineage-negative (Lin−) Sca-1+c-kit+ (KSL)-CD34− cells, which were sorted from the BM of transgenic mice that constitutively express enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP), into lethally irradiated nontransgenic mice. Then we examined the cell fate potential of transplanted EGFP+ cells after liver injury induced by carbon tetrachloride (CCl4). Our findings indicate that cells derived from adult BM hematopoietic stem cells reproducibly transdifferentiate into the hepatic stellate cells of adult recipients after liver injury, without cell fusion.

Methods

Mice

Breeding pairs of C57BL/6-Ly5.1 mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Breeding pairs of transgenic EGFP mice (C57BL/6-Ly5.2 back ground)25 were kindly provided by Dr M. Okabe (Osaka University, Suita, Japan). The 2 strains of mice were bred and maintained at the Animal Research Facility of Mie Graduate School of Medicine. All aspects of the animal research were conducted in accordance with the guidelines set by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Mie Graduate School of Medicine.

Antibodies and cytokines

Purified or phycoerythrin (PE)–conjugated rat anti–mouse Gr-1, purified or PE-conjugated rat anti–mouse CD45R/B220, purified rat anti–mouse CD4, purified rat anti–mouse CD8, purified rat anti–mouse TER-119, PE-conjugated rat anti–mouse Sca-1, allophycocyanin (APC)–conjugated rat anti–mouse c-kit, biotinylated rat anti–mouse CD34, PE-conjugated rat anti–mouse Mac-1, PE-conjugated rat anti–mouse Thy-1.2, mouse lineage panel (biotinylated rat anti–mouse Gr-1, biotinylated rat anti–mouse CD45R/B220, biotinylated hamster anti–mouse CD3e and biotinylated rat anti–mouse TER-119), purified rat anti–mouse CD45, and streptavidin-conjugated PharRed were purchased from BD Biosciences Pharmingen (San Diego, CA). APC-conjugated rat anti–mouse F4/80 was from Caltag (Burlingame, CA). Polyclonal rabbit anti-GFP was from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). Polyclonal rabbit anti–cow GFAP was from DAKO Cytomation (Carpinteria, CA). Polyclonal goat anti-vimentin was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Polyclonal rabbit anti-vimentin and polyclonal rabbit anti–human ADAMTS13 were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Polyclonal rabbit anti–collagen I was from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). Cyanine 3 (Cy3)–conjugated monoclonal mouse anti–α-SMA was from Sigma-Aldrich. Cy3-conjugated mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) was from Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA). Alexa Fluor 546–conjugated goat anti–rabbit IgG and Alexa Fluor 568–conjugated secondary antibodies against primary antibodies of rat, rabbit, and goat origin were purchased from Molecular Probes.

Recombinant mouse steel factor (SF) was provided by Kirin Brewery (Takasaki, Japan) and used at a concentration of 100 ng/mL. Recombinant human interleukin-11 (IL-11) was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN) and used at a concentration of 100 ng/mL.

Cell preparation

Male EGFP mice 10 to 12 weeks old were used as BM donors. The mice were euthanized by isoflurane (Dainippon Pharmaceutical, Osaka, Japan) inhalation, and BM total nucleated cells (TNCs) were flushed from femurs and tibiae, pooled, and washed twice with Ca2+/Mg2+-free phosphate-buffered saline (PBS−; Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) containing 0.1% deionized fraction V bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma-Aldrich). Mononuclear cells (MNCs) were isolated by gradient separation using Lympholyte-M (Cedarlane, Hornby, ON), and Lin− cells were prepared by negative selection using anti–Gr-1, anti-CD45R/B220, anti-CD4, anti-CD8, anti–TER-119, and immunomagnetic beads (Dynabeads M-450 coupled to sheep anti–rat IgG; Dynal, Great Neck, NY). The resulting Lin− cells were stained with PE-conjugated anti–Sca-1, APC-conjugated anti–c-kit, and biotinylated anti-CD34, and mouse lineage panel, followed by streptavidin-conjugated PharRed. KSL-CD34− cells26 were enriched by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) with a FACSAria sorter (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). For clonal cell transplantation, using a single-cell deposition device on a FACSAria, single KSL-CD34− cells were deposited into round-bottomed 96-well plates (Corning, Corning, NY) containing α-modification of Eagle medium (ICN Biomedicals, Aurora, OH), 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone, Logan, UT), 1% deionized fraction V BSA, 10−4 M 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich), SF, and IL-11. The plates were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 in air. At 18 hours after single-cell deposition, the wells containing single cells were marked and incubated for a total of 7 days. We selected clones consisting of no more than 20 cells after incubation for clonal cell transplantation.

Transplantation

Male C57BL/6-Ly5.1 mice 10 to 12 weeks old were used as irradiated recipients and given a single 950-cGy dose of total body irradiation using a 4 × 106 V linear accelerator. Clonal cell transplantation was carried out using modification of the method we previously described.22,23 The contents of the wells containing 20 or fewer viable clusters of cells derived from single cells were injected into the tail veins of irradiated Ly-5.1 mice together with 2 × 105 Sca-1− BM MNCs, which served as radioprotective cells during the postradiation pancytopenia period, taken from Ly-5.1 mice.

To generate BM TNC transplants in mice, we also injected 106 BM TNCs obtained from male EGFP mice without any radioprotective cells into irradiated male Ly-5.1 mice through their tail veins.

Flow cytometric analysis of hematopoietic engraftment

For analysis of hematopoietic engraftment, peripheral blood (PB) was obtained from the retro-orbital plexus of the recipient mice using heparin-coated micropipettes (Drummond Scientific, Broomall, PA). Red blood cells were lysed with 0.15 M NH4Cl. The percentage of donor-derived cells (EGFP+) in B-cell, T-cell, and myeloid lineages was analyzed by staining with PE-conjugated anti-CD45R/B220, anti–Thy-1.2, and a combination of anti–Gr-1 and anti–Mac-1, respectively.

Induction of liver-injured mice

We induced liver injury in mice receiving transplants by CCl4 treatment at 2 months after BM transplantation. Mice receiving transplants were intraperitoneally injected with 7 mL/kg body weight of a 1:4 solution of CCl4 (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan) and olive oil (Wako Pure Chemical Industries) twice a week for more than 3 months. Control mice were intraperitoneally injected with olive oil only.

Tissue processing

Mice were anesthetized with inhalation of isoflurane and intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital (Dainippon Pharmaceutical) and then perfused through the left ventricle with 25 mL PBS− followed by 25 mL of 4% phosphate-buffered paraformaldehyde (PFA; Wako Pure Chemical Industries) before livers were isolated by dissection. The livers were fixed in 4% phosphate-buffered PFA for 1 hour at room temperature. Some tissue blocks were embedded in paraffin after dehydration with graded alcohol series. Other tissue blocks were fixed with 4% phosphate-buffered PFA for another 4 hours and embedded in Tissue-Tek OCT medium (Sakura Finetek USA, Torrance, CA), rapidly frozen by plunging into liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until required for cryosectioning. The tissue blocks were cut to 5-μm sections using a microtome or a cryostat.

Histologic analysis

To evaluate the presence of fibrosis, livers were obtained from mice that had received BM TNC transplants, with or without CCl4 treatment. Serial sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin and azan and were examined using an Olympus BX50 light microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a 10×/0.40 numeric aperture (NA) objective lens and an Olympus DP70 charge-coupled device (CCD) camera (Olympus). Images were acquired using DP Manager software (Olympus) and were processed using Adobe Photoshop CS (Adobe Systems, Tokyo, Japan).

Immunohistochemical analysis

Fluorescent immunohistochemistry was performed on frozen sections using purified monoclonal rat anti–mouse CD45, polyclonal rabbit anti-GFP, polyclonal goat anti-vimentin, polyclonal rabbit anti-GFAP, and polyclonal rabbit anti-ADAMTS13 followed by Alexa Fluor 568–conjugated secondary antibodies. As negative controls, immunohistostaining was performed without the first antibody. Frozen sections stained with Cy3-conjugated anti–α-SMA were pretreated with the M.O.M. Kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), and Cy3-conjugated purified mouse IgG was used as negative control. Nuclei were stained with TO-PRO-3 iodide (Molecular Probes). For triple-fluorescent immunohistochemistry, sections were incubated with APC-conjugated rat anti–mouse F4/80 and purified monoclonal rat anti–mouse CD45, followed by Alexa Fluor 568–conjugated goat anti–rat IgG antibody.

To permit examination of lipid droplets stained by oil red O (ORO) together with fluorescent immunohistochemistry, we used a modification of the method of Koopman et al.27 ORO (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved to a stock solution by adding 150 mg ORO to 50 mL isopropanol (Wako Pure Chemical Industries). Before staining, a 60% isopropanol working solution was prepared with distilled water. This solution was filtered to remove crystallized ORO. Frozen sections were treated with 0.5% Triton X-100 (Wako Pure Chemical Industries) in PBS− for 1 hour and washed 3 times with PBS− for 5 minutes. Sections were incubated for 2 hours at room temperature with a primary antibody at the appropriate dilution and washed 3 times with PBS− for 5 minutes. Then, the appropriate Alexa Fluor 568–conjugated secondary antibody was applied for 2 hours at room temperature. After washing for 5 minutes 3 times with PBS−, sections were stained for 20 minutes at room temperature in freshly prepared ORO solution followed by rinsing with PBS−. All sections were examined with an Olympus IX81 FV1000 laser scanning confocal microscope using 40×/1.30 or 60×/1.42 NA oil-immersion objective lenses (Olympus) at room temperature. Visualization of lipid with ORO staining was obtained by excitation with the 647-nm laser line.28 Images were acquired using FV10-ASW software (Ver 1.3; Olympus) and processed using Adobe Photoshop CS.

Isolation and culture of hepatic nonparenchymal cells

Hepatic nonparenchymal cells were isolated using a modification of the method of Tateno et al29 and Riccalton-Banks et al.30 Livers were perfused via the heart with 25 mL liver perfusion medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and 25 mL liver digestion medium (Invitrogen) after anesthesia with isoflurane and pentobarbital, and were digested with liver digestion medium. The digested liver cells were filtered through a 70-μm nylon cell strainer (BD Biosciences Discovery Labware, Bedford, MA) to eliminate nondigested material and were centrifuged 3 times at 50g for 1 minute. The supernatant was centrifuged 3 times at 150g for 5 minutes. The pellet was resuspended in proline-free Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (Invitrogen) and centrifuged at 50g for 2 minutes. The supernatant was used as a fraction of nonparenchymal cells. These fractioned cells were inoculated on uncoated Lab-Tek II chamber slides (Nalge Nunc International, Naperville, IL) and incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 in air for 3 or 4 days. The culture medium consisted of proline-free Dulbecco modified Eagle medium, 10% FBS, 100 IU/mL penicillin G, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Invitrogen).

Immunocytochemical analysis for cultured cells

For immunocytochemical staining, cultured nonparenchymal cells were fixed with 4% phosphate-buffered PFA for 1 hour at room temperature. Cells were incubated overnight at 4°C with polyclonal rabbit anti-ADAMTS13 and polyclonal rabbit anti–collagen I diluted in PBS− containing 0.1% saponin and 0.4% BSA. After washing 3 times, cells were incubated in Alexa Fluor 568–conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 hour at 37°C. After washing 3 times with PBS−, slides were stained for 20 minutes at room temperature in freshly prepared ORO solution followed by rinsing with PBS−. Images were obtained using an Olympus IX81 FV1000 laser scanning confocal microscope equipped with 60×/1.42 NA oil-immersion objective lens and processed using Adobe Photoshop CS.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis of mouse Y chromosome

Frozen sections were hybridized for Y chromosome identification using a DNA painting probe for the Y chromosome (Chromosome Science Labo, Sapporo, Japan). Images of natural EGFP fluorescence were obtained before hybridization using a Leica DMRA2 microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) equipped with a 40×/0.7 PL Fluotar objective lens, DC350FX CCD camera, and CW4000FISH software (all from Leica Microsystems). The specimens were subjected to protease digestion using 0.02% pepsin/0.1 N HCl for 2 minutes at 37°C. After applying 10 μL of a Cy3-conjugated DNA probe, the specimens and the probes were denatured simultaneously for 10 minutes at 80°C and then incubated for 16 hours at 37°C. Nuclei were stained with 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Sigma-Aldrich). Images of the nuclei of the same cells photographed before the fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) were taken as stated earlier in this paragraph. Images were manipulated using Adobe Photoshop 7.0 (Adobe Systems, Mountain View, CA).

We next performed a 2-step procedure on cultured hepatic nonparenchymal cells: immunostaining with polyclonal rabbit anti-vimentin followed by Alexa Fluor 546–conjugated goat anti–rabbit IgG and DAPI, followed by FISH of the same cells using a Cy3-conjugated DNA probe for the Y chromosome and restaining with DAPI. The images were obtained using a Leica DMRA2 and CW4000FISH software. The fields of the immunostaining and FISH images were matched according to the location and the nuclear distribution to be as close to each other as possible. Adobe Photoshop 7.0 was used for image processing.

Results

BM-derived cells are present in fibrotic liver

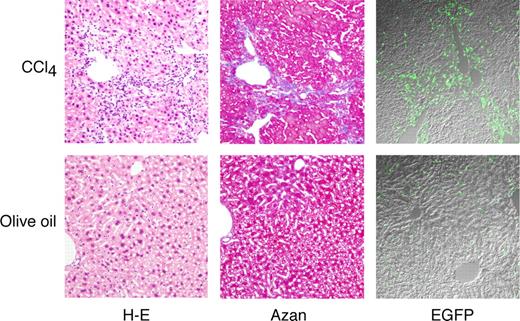

At first, we generated EGFP+ BM TNC–transplanted chimeric mice. CCl4 intoxication was used as a model of hepatic fibrosis because of its simplicity and reproducibility.14,21,31 BM TNCs from male EGFP mice were transplanted into lethally irradiated male Ly-5.1 mice, and CCl4 injection was started at 2 months after transplantation to induce hepatic fibrosis. After more than 12 weeks of administration of CCl4, livers were enlarged and had irregular surfaces with some nodules (data not shown). As shown in Figure 1, on light microscopy, a large number of small cells infiltrated the area around the portal tracts and central veins in the livers of mice treated with CCl4 (top left). Collagen deposition was detected by azan staining, and liver fibrosis was evident with the formation of nodules and bridging fibrosis (top middle). Fluorescence microscopy revealed many EGFP+ cells in the livers, and the majority were present in the nonparenchymal region (top right). Immunostaining of EGFP+ cells with anti-GFP antibody confirmed the specificity of the fluorescent GFP signal (data not shown). On the other hand, the livers obtained from olive oil–treated mice were almost normal (bottom left and middle). A few EGFP+ cells were detected (bottom right). We performed subsequent experiments using this CCl4-mediated liver injury model.

Microscopic features of livers after 12 weeks of CCl4 treatment. Mice that had received EGFP+ BM TNC transplants were treated with olive oil or CCl4 for 12 weeks, and livers of the mice were examined microscopically. Serial sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H-E) and azan. Original magnification, ×100. Staining was analyzed using an Olympus BX50 light microscope equipped with a 10×/0.40 NA objective lens, an Olympus DP70 CCD camera, and DP Manager software, and images were processed using Adobe Photoshop CS. Simultaneous differential interference contrast and EGFP images were also acquired using an Olympus IX81 FV1000 laser scanning confocal microscope equipped with 20×/0.75 NA objective lens and using FV10-ASW software. Images were processed using Adobe Photoshop CS.

Microscopic features of livers after 12 weeks of CCl4 treatment. Mice that had received EGFP+ BM TNC transplants were treated with olive oil or CCl4 for 12 weeks, and livers of the mice were examined microscopically. Serial sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H-E) and azan. Original magnification, ×100. Staining was analyzed using an Olympus BX50 light microscope equipped with a 10×/0.40 NA objective lens, an Olympus DP70 CCD camera, and DP Manager software, and images were processed using Adobe Photoshop CS. Simultaneous differential interference contrast and EGFP images were also acquired using an Olympus IX81 FV1000 laser scanning confocal microscope equipped with 20×/0.75 NA objective lens and using FV10-ASW software. Images were processed using Adobe Photoshop CS.

Generation of chimeric mice receiving transplants of clonal populations of cells derived from single hematopoietic stem cells

To test the hypothesis that hepatic stellate cells may be derived from hematopoietic stem cells, we then generated chimeric mice by transplantation of clonal populations of cells descended from single EGFP+ hematopoietic stem cells (mice that received clonal cell transplants). We combined single-cell deposition with short-term cell culture to achieve a high efficiency of clonal hematopoietic engraftment.22,23 Clonal populations of cells derived from single EGFP+KSL-CD34− cells were transplanted into lethally irradiated recipient mice. At 2 months after transplantation, analysis of nucleated peripheral blood cells from the mice that had received clonal cell transplants revealed variable levels of hematopoietic chimerism and lineage combinations. Approximately 13% (8 of 64 mice) of mice that received clonal cell transplants showed high levels of long-term, multilineage hematopoietic engraftment. Table 1 shows the degree of reconstitution of myeloid, B-cell, and T-cell lineages in the 8 mice. The percentage range of EGFP+ cells in myeloid, B cell, and T-cell lineages was 13% to 86%, 10% to 86%, and 4% to 50%, respectively. Thereafter, CCl4 was administrated to induce liver fibrosis in these chimeric mice.

Hematopoietic engraftment

| Mouse . | Cell no.* (day 7) . | Chimerism, % EGFP+ cells . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gr-1+/Mac-1+ . | B220+ . | Thy-1.2+ . | ||

| 1 | 5 | 86 | 86 | 28 |

| 2 | 12 | 69 | 78 | 36 |

| 3 | 6 | 30 | 46 | 12 |

| 4 | 8 | 84 | 72 | 50 |

| 5 | 2 | 76 | 82 | 40 |

| 6 | 3 | 13 | 10 | 4 |

| 7 | 4 | 66 | 72 | 24 |

| 8 | 18 | 71 | 34 | 33 |

| Mouse . | Cell no.* (day 7) . | Chimerism, % EGFP+ cells . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gr-1+/Mac-1+ . | B220+ . | Thy-1.2+ . | ||

| 1 | 5 | 86 | 86 | 28 |

| 2 | 12 | 69 | 78 | 36 |

| 3 | 6 | 30 | 46 | 12 |

| 4 | 8 | 84 | 72 | 50 |

| 5 | 2 | 76 | 82 | 40 |

| 6 | 3 | 13 | 10 | 4 |

| 7 | 4 | 66 | 72 | 24 |

| 8 | 18 | 71 | 34 | 33 |

Each cell number presents the number of cells contained in individual well on day 7 of culture with SF and IL-11. The entire contents of each well were transplanted into lethally irradiated recipient mice.

Increase of CD45−EGFP+ cells in the CCl4-treated liver

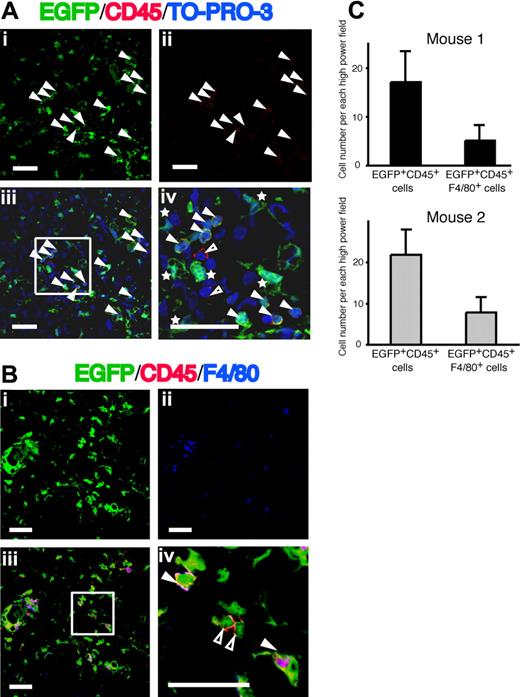

After 12 weeks of CCl4 treatment, the livers were harvested from 3 mice that had received clonal cell transplants (mice 1-3 in Table 1) revealing high-level multilineage engraftment. A large number of EGFP+ cells were found in the liver, especially in the periportal and pericentral area (Figure 2Ai). Because all hematopoietic cells except erythrocytes express CD45, we analyzed the expression of CD45 on the EGFP+ cells to clarify whether they were hematopoietic cells. There were some CD45+ hematopoietic cells in the same area (Figure 2Aii). Counterstaining with TO-PRO-3 was used to identify the nucleus. We found EGFP+CD45+ cells, EGFP+CD45− cells, and very few EGFP−CD45+ cells in the liver (Figure 2Aiii,iv). The numbers of EGFP+ cells and EGFP+CD45+ cells per high-power field were 33 and 13 in mouse 1, 42 and 20 in mouse 2, and 12 and 6 in mouse 3, respectively (Table 2). The number of EGFP+ cells in the liver correlated with the level of hematopoietic engraftment in each mouse that had received a clonal cell transplant. The percentage of CD45+ cells in the EGFP+ cells was almost constant in these 3 mice. These data indicate that approximately 50% to 60% of EGFP+ cells in the liver were negative for CD45. On the other hand, in mice that received BM-TNC tranplants and that exhibited high levels of multilineage engraftment (88%-93%), the number of EGFP+ cells and EGFP+CD45+ cells per high-power field was similar to that in mice that had received clonal cell transplants (Table 2). Accordingly, EGFP+ nonhematopoietic cells in the liver are likely to be derived from donor hematopoietic stem cells after CCl4 administration. Because it has been reported that Kupffer cells in the liver are hematopoietic in origin,32,33 we analyzed the expression of F4/80, which is a marker of Kupffer cells, and CD45 on EGFP+ cells. All EGFP+F4/80+ cells were CD45+ (Figure 2Biii,iv) and consisted of a third of EGFP+CD45+ cells (Figure 2C).

Distribution of EGFP+ cells in the livers from mice that had received clonal cell transplants with CCl4 treatment. (A) Panel i shows EGFP as green and panel ii shows CD45 as red. Panels iii and iv show the merged images of EGFP, Alexa Fluor 568-labeled anti-CD45, and TO-PRO-3. Nuclei were stained with TO-PRO-3. White triangles indicate cells expressing both EGFP and CD45. White asterisks and open triangles show EGFP+CD45− cells and EGFP−CD45+ cells, respectively. Bars equal 30 μm. Images were acquired using an Olympus IX81 FV1000 laser scanning confocal microscope equipped with 40×/1.30 NA oil-immersion objective lens and using FV10-ASW software (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Images were processed using Adobe Photoshop CS. (B) Panel i shows EGFP as green and panel ii shows F4/80 as blue. Panels iii and iv show the merged images of EGFP, Alexa Fluor 568–labeled anti-CD45, and APC-labeled anti-F4/80. White triangles indicate cells expressing EGFP, CD45 and F4/80. Open triangles show EGFP+CD45+F4/80− cells. Bars equal 30 μm. Images were acquired and processed as in panel A. (C) The numbers of EGFP+CD45+ cells and EGFP+CD45+F4/80+ cells in the livers from 2 mice that had received clonal cell transplants. Data are means plus or minus a standard deviation.

Distribution of EGFP+ cells in the livers from mice that had received clonal cell transplants with CCl4 treatment. (A) Panel i shows EGFP as green and panel ii shows CD45 as red. Panels iii and iv show the merged images of EGFP, Alexa Fluor 568-labeled anti-CD45, and TO-PRO-3. Nuclei were stained with TO-PRO-3. White triangles indicate cells expressing both EGFP and CD45. White asterisks and open triangles show EGFP+CD45− cells and EGFP−CD45+ cells, respectively. Bars equal 30 μm. Images were acquired using an Olympus IX81 FV1000 laser scanning confocal microscope equipped with 40×/1.30 NA oil-immersion objective lens and using FV10-ASW software (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Images were processed using Adobe Photoshop CS. (B) Panel i shows EGFP as green and panel ii shows F4/80 as blue. Panels iii and iv show the merged images of EGFP, Alexa Fluor 568–labeled anti-CD45, and APC-labeled anti-F4/80. White triangles indicate cells expressing EGFP, CD45 and F4/80. Open triangles show EGFP+CD45+F4/80− cells. Bars equal 30 μm. Images were acquired and processed as in panel A. (C) The numbers of EGFP+CD45+ cells and EGFP+CD45+F4/80+ cells in the livers from 2 mice that had received clonal cell transplants. Data are means plus or minus a standard deviation.

Engraftment of donor-derived cells in the injured liver of mice transplanted with either clonal cells from KSL-CD34− cells or BM TNCs

| Cells transplanted . | Cells . | CD45+ cells in EGFP+ cells, % . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| EGFP+ cells . | EGFP+CD45+ cells . | ||

| Clonal cells | |||

| 1 | 33.1 ± 9.9 | 12.6 ± 2.5 | 38.1 |

| 2 | 42.1 ± 9.8 | 20.0 ± 3.8 | 47.5 |

| 3 | 12.0 ± 3.4 | 6.3 ± 0.9 | 52.5 |

| BM TNCs | |||

| 1 | 31.6 ± 6.6 | 11.5 ± 3.9 | 37.6 |

| 2 | 29.2 ± 10.2 | 14.9 ± 4.2 | 51.0 |

| 3 | 25.9 ± 5.1 | 12.2 ± 2.5 | 47.1 |

| Cells transplanted . | Cells . | CD45+ cells in EGFP+ cells, % . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| EGFP+ cells . | EGFP+CD45+ cells . | ||

| Clonal cells | |||

| 1 | 33.1 ± 9.9 | 12.6 ± 2.5 | 38.1 |

| 2 | 42.1 ± 9.8 | 20.0 ± 3.8 | 47.5 |

| 3 | 12.0 ± 3.4 | 6.3 ± 0.9 | 52.5 |

| BM TNCs | |||

| 1 | 31.6 ± 6.6 | 11.5 ± 3.9 | 37.6 |

| 2 | 29.2 ± 10.2 | 14.9 ± 4.2 | 51.0 |

| 3 | 25.9 ± 5.1 | 12.2 ± 2.5 | 47.1 |

Sections of livers from transplanted mice were stained for CD45. EGFP+ cells and EGFP+CD45+ cells were counted as described in “Immunohistochemical analysis” as the number of positive cells in each high-power field. Data represent the mean numbers of cells plus or minus the standard deviation or the percentage of CD45+ cells in EGFP+ cells.

KSL indicates Lin−Sca-1+c-kit+.

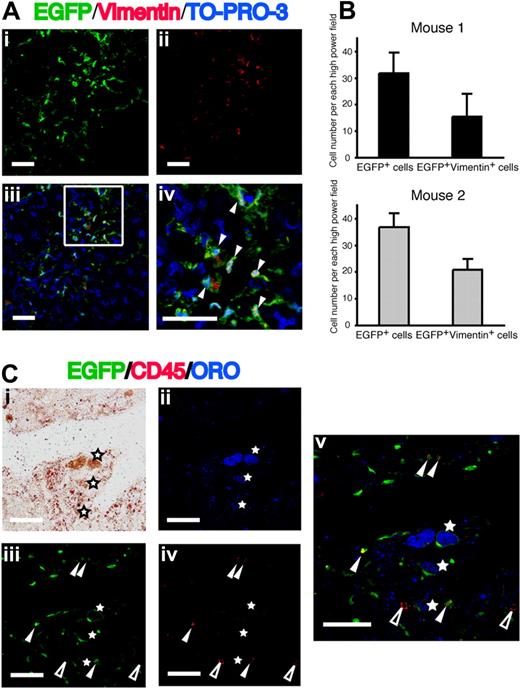

ORO deposition in EGFP+CD45− cells

Because vimentin is one of the main intermediate filament proteins in mesenchymal cells, including hepatic stellate cells,34 we also analyzed the expression of vimentin in the EGFP+ cells (Figure 3A). The number EGFP+vimentin+ cells per high-power field was 16 in mouse 1 and 21 in mouse 2, and approximately half of EGFP+ cells in the injured liver were vimentin positive (Figure 3B). Hepatic stellate cells exist in 2 morphologically distinguishable forms: quiescent type and activated type.1,,,–5 The quiescent hepatic stellate cells are characterized by the presence of intracytoplasmic lipid droplets, which contain vitamin A. The lipid droplets decrease during activation of hepatic stellate cells. To analyze the presence of lipid droplets in EGFP+ cells, we performed ORO staining combined with immunofluorescence assays.27,28 Subpanels i and ii in Figure 3C show the light microscopic image and the fluorescent microscopic image of ORO+ cells, respectively. The majority of these ORO+ cells were positive for EGFP (Figure 3Ciii). However, our concern was whether Kupffer cells could take up lipid droplets released from injured hepatic stellate cells. Therefore, we examined the expression of CD45 on EGFP+ORO+ cells. All EGFP+ORO+ cells were negative for CD45 (Figure 3Civ,v), a finding indicating that they are not Kupffer cells.

Expression of vimentin and ORO in EGFP+ cells in the fibrotic liver. (Ai) EGFP as green. (ii) Vimentin as red. (iii,iv) Merged images of EGFP, Alexa Fluor 568–labeled anti-vimentin, and TO-PRO-3. Nuclei were stained with TO-PRO-3. White triangles indicate cells expressing both EGFP and vimentin. Bars equal 30 μm. Images were acquired and processed as in Figure 2A. (B) The numbers of EGFP+ cells and EGFP+vimentin+ cells in the livers from 2 clonal cells–transplanted mice. Data are means plus or minus a standard deviations. (C) Liver sections were stained with ORO (red in panel i; blue in panel ii) and Alexa Fluor 568–labeled anti-CD45 (red in panel iv). (iii) EGFP as green. (v) A merged image of panels ii, iii, and iv. EGFP+ORO+ cells (white asterisks) are negative for CD45. White triangles and open triangles indicate EGFP+CD45+ cells and EGFP−CD45+ cells, respectively. Bars equal 30 μm. Images were acquired and processed as in Figure 2A.

Expression of vimentin and ORO in EGFP+ cells in the fibrotic liver. (Ai) EGFP as green. (ii) Vimentin as red. (iii,iv) Merged images of EGFP, Alexa Fluor 568–labeled anti-vimentin, and TO-PRO-3. Nuclei were stained with TO-PRO-3. White triangles indicate cells expressing both EGFP and vimentin. Bars equal 30 μm. Images were acquired and processed as in Figure 2A. (B) The numbers of EGFP+ cells and EGFP+vimentin+ cells in the livers from 2 clonal cells–transplanted mice. Data are means plus or minus a standard deviations. (C) Liver sections were stained with ORO (red in panel i; blue in panel ii) and Alexa Fluor 568–labeled anti-CD45 (red in panel iv). (iii) EGFP as green. (v) A merged image of panels ii, iii, and iv. EGFP+ORO+ cells (white asterisks) are negative for CD45. White triangles and open triangles indicate EGFP+CD45+ cells and EGFP−CD45+ cells, respectively. Bars equal 30 μm. Images were acquired and processed as in Figure 2A.

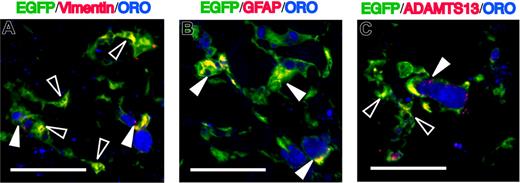

Expression of markers for hepatic stellate cells in EGFP+ORO+ cells

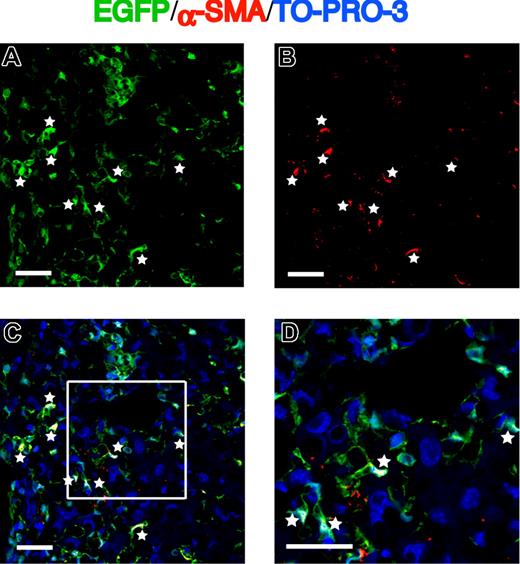

To further characterize the phenotype of EGFP+ORO+ cells, we investigated the expression of markers associated with hepatic stellate cells using triple-immunofluorescence experiments. GFAP is also an intermediate filament protein generally considered to be specific for astroglial cells, and it represents an invaluable marker for the positive identification of hepatic stellate cells.12,–14 As shown in Figure 4A,B, EGFP+ORO+ cells stained positive for vimentin and GFAP, and these phenotypes are consistent with those of quiescent hepatic stellate cells. A disintegrin-like and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin type-1 motifs 13 (ADAMTS13) is a metalloproteinase that specifically cleaves the multimeric von Willebrand factor and is known to be specifically expressed in hepatic stellate cells.35,,,,–40 As shown in Figure 4C, ADAMTS13 was positive in EGFP+ORO+ cells. We found that vimentin and ADAMTS13 also were expressed in some EGFP+ORO− cells (Figure 4A,C). During liver injury, the hepatic stellate cells undergo activation, lose intracytoplasmic lipid droplets, and transform into a myofibroblast phenotype expressing α-SMA, a marker of activated hepatic stellate cells.2,5,17 Then, we analyzed the expression of α-SMA in EGFP+ cells. Some cells coexpressed EGFP and α-SMA and developed a myofibroblast-like morphology in the injured liver (Figure 5). These findings indicate that hematopoietic stem cell–derived cells can give rise to both quiescent and activated hepatic stellate cells during liver injury.

Characteristics of EGFP+ORO+ cells in the fibrotic liver. Sections were immunostained with anti-vimentin (A), anti-GFAP (B), or anti-ADAMTS13 (C), followed by Alexa Fluor 568–conjugated secondary antibody. EGFP+ORO+ cells are positive for vimentin, GFAP, and ADAMTS13. White triangles indicate cells coexpressing EGFP, ORO, and the respective markers. Open triangles indicate EGFP+ORO−vimentin+ cells (A) or EGFP+ORO−ADAMTS13+ cells (C). Bars equal 30 μm. Images were acquired using an Olympus IX81 FV1000 laser scanning confocal microscope equipped with 60×/1.42 NA oil-immersion objective lenses and using FV10-ASW software. Images were processed using Adobe Photoshop CS.

Characteristics of EGFP+ORO+ cells in the fibrotic liver. Sections were immunostained with anti-vimentin (A), anti-GFAP (B), or anti-ADAMTS13 (C), followed by Alexa Fluor 568–conjugated secondary antibody. EGFP+ORO+ cells are positive for vimentin, GFAP, and ADAMTS13. White triangles indicate cells coexpressing EGFP, ORO, and the respective markers. Open triangles indicate EGFP+ORO−vimentin+ cells (A) or EGFP+ORO−ADAMTS13+ cells (C). Bars equal 30 μm. Images were acquired using an Olympus IX81 FV1000 laser scanning confocal microscope equipped with 60×/1.42 NA oil-immersion objective lenses and using FV10-ASW software. Images were processed using Adobe Photoshop CS.

Expression of α-SMA in EGFP+ cells migrating into the fibrotic liver. (A) EGFP as green. (B) α-SMA as red. (C,D) Merged images of EGFP, Cy3-labeled α-SMA, and TO-PRO-3. White asterisks indicate cells expressing both EGFP and α-SMA. Bars equal 30 μm. Images were acquired and processed as in Figure 2A.

Expression of α-SMA in EGFP+ cells migrating into the fibrotic liver. (A) EGFP as green. (B) α-SMA as red. (C,D) Merged images of EGFP, Cy3-labeled α-SMA, and TO-PRO-3. White asterisks indicate cells expressing both EGFP and α-SMA. Bars equal 30 μm. Images were acquired and processed as in Figure 2A.

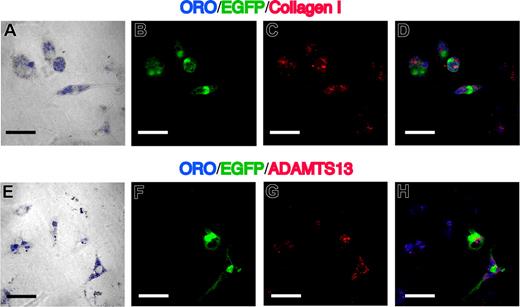

Production of collagen I and ADAMTS13 in cultured EGFP+ nonparenchymal cells

Although location and immunohistochemical findings of EGFP+ cells on the frozen sections strongly suggest that EGFP+ cells are hepatic stellate cells, we carried out cell culture experiments to evaluate the ability of these cells to produce collagen I and ADAMTS13 at a single-cell level. Isolated nonparenchymal cells were incubated on noncoated Lab-Tek II chamber slides without any cytokines for 3 days. The cultured cells displayed stellate-like morphology. Almost all EGFP+ cells were positive for ORO, and collagen I and ADAMTS13 were expressed in these EGFP+ORO+ cells (Figure 6D,H). These data reveal that hematopoietic stem cell–derived hepatic stellate cells can synthesize both collagen I and ADAMTS13.

Characteristics of cultured nonparenchymal cells in the fibrotic liver. (A,E) Phase-contrast image merged with ORO (blue) of 3-day–cultured nonparenchymal cells, which were isolated from livers of mice that had received clonal cell transplants and were treated with CCl4. (B,F) EGFP as green. (C,G) Immunofluorescent images with collagen I (C) and ADAMTS13 (G). (D,H) Merged images of ORO, EGFP, and collagen I or ADAMTS13. EGFP+ORO+ cells are positive for collagen I and ADAMTS13. Bars equal 30 μm. Images were acquired and processed as in Figure 4.

Characteristics of cultured nonparenchymal cells in the fibrotic liver. (A,E) Phase-contrast image merged with ORO (blue) of 3-day–cultured nonparenchymal cells, which were isolated from livers of mice that had received clonal cell transplants and were treated with CCl4. (B,F) EGFP as green. (C,G) Immunofluorescent images with collagen I (C) and ADAMTS13 (G). (D,H) Merged images of ORO, EGFP, and collagen I or ADAMTS13. EGFP+ORO+ cells are positive for collagen I and ADAMTS13. Bars equal 30 μm. Images were acquired and processed as in Figure 4.

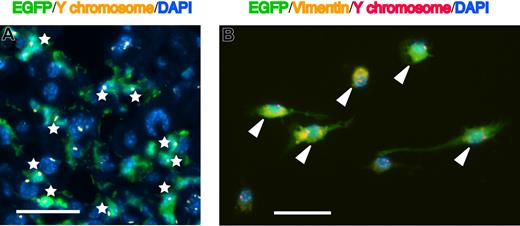

Mechanisms underlying generation of EGFP+ hepatic stellate cells

Recently, several investigators have reported that some of the data describing stem-cell plasticity may be the result of spontaneous cell fusion.41,42 To exclude the possibility that our observations could be attributable to fusion of hematopoietic stem cell–derived cells with resident hepatic stellate cells, we analyzed sections of livers from Ly-5.1 male mice that received transplants of clonal cell populations derived from single KSL-CD34− cells from EGFP male mice (male-to-male transplanted mice) using FISH for Y chromosome. We analyzed 200 EGFP+ cells and observed no EGFP+ cells with 2 Y chromosomes (Figure 7A). Furthermore, we analyzed cultured hepatic nonparenchymal cells from male-to-male transplant recipient mice that received transplants for the combined expression of EGFP, vimentin, and the presence of multiple Y chromosomes. As shown in Figure 7B, all 65 EGFP+vimentin+ cells counted had only one Y chromosome. These observations negate the possibility that EGFP+ hepatic stellate cells are generated by spontaneous cell fusion.

FISH analysis of Y chromosome in the hepatic stellate cells. (A) Merged image of EGFP (green), Cy3-conjugated Y chromosome paint probe (yellow dots), and DAPI nuclear counterstain (blue) in the liver of mice that had received clonal cell transplants. White asterisks indicate EGFP+ cells with only one Y chromosome. Original magnification, ×400. Bar equals 30 μm. Images were obtained by a Leica DMRA2 equipped with a 40×/0.7 PL Fluotar objective lens, a DC350FX CCD camera, and CW4000FISH software. Images were processed using Adobe Photoshop 7.0. (B) Merged image of EGFP (green), vimentin (yellow), Cy3-conjugated Y chromosome paint probe (red dots), and DAPI (blue) in 3-day–cultured nonparenchymal cells, which were isolated from the livers of mice that had received clonal cell transplants and were treated with CCl4. White triangles indicate EGFP+vimentin+ cells with only one Y chromosome. Original magnification, ×400. Bar equals 30 μm. Images were acquired and processed as in panel A.

FISH analysis of Y chromosome in the hepatic stellate cells. (A) Merged image of EGFP (green), Cy3-conjugated Y chromosome paint probe (yellow dots), and DAPI nuclear counterstain (blue) in the liver of mice that had received clonal cell transplants. White asterisks indicate EGFP+ cells with only one Y chromosome. Original magnification, ×400. Bar equals 30 μm. Images were obtained by a Leica DMRA2 equipped with a 40×/0.7 PL Fluotar objective lens, a DC350FX CCD camera, and CW4000FISH software. Images were processed using Adobe Photoshop 7.0. (B) Merged image of EGFP (green), vimentin (yellow), Cy3-conjugated Y chromosome paint probe (red dots), and DAPI (blue) in 3-day–cultured nonparenchymal cells, which were isolated from the livers of mice that had received clonal cell transplants and were treated with CCl4. White triangles indicate EGFP+vimentin+ cells with only one Y chromosome. Original magnification, ×400. Bar equals 30 μm. Images were acquired and processed as in panel A.

Discussion

There are substantial scientific data to support that hepatic stellate cells in the adult liver are derived from BM cells in mouse.20,21 Because BM contains mesenchymal stem cells as well as hematopoietic stem cells, it remains unclear which BM subpopulations are the true origins of hepatic stellate cells. Our purpose was to identify the origin of hepatic stellate cells in adult liver. The present study demonstrates that BM hematopoietic stem cells can give rise to hepatic stellate cells through liver injury.

It has been recognized recently that adult hematopoietic stem cells play a part in the regeneration of a number of nonhematopoietic tissues.43,,,,,–49 However, the plasticity of hematopoietic stem cells and/or their progeny remains controversial for 3 major reasons: (i) most studies examining plasticity have been performed using a heterogenous BM population; (ii) this phenomenon is an extremely rare event in a physiologic state50,–52 ; (iii) fusion of BM-derived cells with host somatic cells has been reported as a major mechanism by which BM-derived cells can contribute to regenerate a variety of nonhematopoietic cells in multiple organs.53,,,–57 To test the potential of hematopoietic stem cells to transdifferentiate into nonhematopoietic tissues, we generated chimeric mice by transplantation of clones from a single EGFP+KSL-CD34− hematopoietic stem cell, which was sorted from BM of EGFP mice. We had already observed that hematopoietic stem cells are able to reconstitute the glomerular mesangial cells in kidney without fusion.22 However, we could not detect any other EGFP+ nonhematopoietic cells in the chimeric mice under physiologic conditions. This finding is consistent with that reported by Wagers et al.50 Therefore, we have previously developed some injury models using chimeric mice and found that hematopoietic stem cells can differentiate into perivascular pericyte-like cells in the brain after cerebral ischemia.23 In this study, we evaluated the cell fate potential of hematopoietic stem cells in the setting of a liver fibrosis using the chimeric mice and a CCl4-induced liver injury model.

We first examined whether hematopoietic stem cell–derived nonhematopoietic cells were present in the injured liver based on morphologic characteristics and cell surface/intracytoplasmic protein expression. It is well accepted that there are 3 types of hepatic nonparenchymal cells: Kupffer cells, sinusoidal endothelial cells, and hepatic stellate cells. Kupffer cells differ from other cells because of the expression of CD45.32,33 Sinusoidal endothelial cells can be easily distinguished from hepatic stellate cells, the latter being characterized by numerous lipid droplets, a feature that was never found in the former.58 We found that 50% to 60% of EGFP+ cells in the CCl4-treated livers were negative for CD45. Some EGFP+CD45− cells contained intracytoplasmic lipid droplets, which were proven by ORO staining.59 These EGFP+ORO+ cells also expressed vimentin and GFAP, and some EGFP+ cells were positive for α-SMA. These phenotypes are consistent with those of quiescent and activated hepatic stellate cells. Because α-SMA is expressed not only in activated hepatic stellate cells but also in hepatic myofibroblasts,2,21 our findings raise the possibility that hepatic myofibroblasts also arise from hematopoietic stem cells. Russo et al21 reported that a predominant source of myofibroblasts expressing α-SMA in the injured liver was the mesenchymal stem cells by transplanting a supraphysiologic number of cultured mesenchymal cells. From our and their results, both hematopoietic stem cells and mesenchymal stem cells may contribute to repopulate the hepatic myofibroblasts during liver injury.

The synthesis of collagen I is an important functional parameter of hepatic stellate cells,6,7 and activated hepatic stellate cells are known to produce large amounts of collagen I. Furthermore, recent studies have revealed that ADAMTS13 is primarily expressed in activated hepatic stellate cells because of colocalization of ADAMTS13 and α-SMA.37,38 Niiya et al39 demonstrated that the dramatic up-regulation of ADAMTS13 and its proteolytic activity during the activation of rat hepatic stellate cells in vitro and in vivo by CCl4 administration may be crucial for the biologic functions of the activated hepatic stellate cells. Of note, we found that some EGFP+ cells synthesized collagen I and ADAMTS13. Because the majority of these EGFP+ cells contained intracytoplasmic lipid droplets, they were thought to have characteristics of both quiescent hepatic stellate cells and activated myofibroblast-like cells. Kent et al3 named these distinctive cells as transitional cells and also reported that they are abundant in the CCl4-injured liver and are associated with the appearance of collagens I and III. Taken together, the majority of hematopoietic stem cell–derived hepatic stellate cells, which we observed in the CCl4-injured livers, were the transitional cells. Moreover, we revealed using FISH for Y chromosome that these hepatic stellate cells did not result from cell fusion, unlike the hematopoietic stem cell–derived hepatocytes.54,55

Our data show that hematopoietic stem cells can give rise to hepatic stellate cells during liver fibrosis. However, the precise differentiation process from hematopoietic stem cells to hepatic stellate cells remains to be elucidated. Abe et al60 examined the relationship between the presence of EGFP+ glomerular mesangial cells and the reconstitution level of individual hematopoietic lineages and found that glomerular mesangial cells share their origin with myeloid lineage cells. Bailey et al61 demonstrated that vascular endothelial cells can arise from common myeloid progenitors and the more mature granulocyte/macrophage progenitors. Meanwhile, Kisseleva et al62 reported that BM-derived fibrocytes were recruited to the damaged liver in response to bile duct ligation–induced injury and that they differentiated into hepatic myofibroblasts after culture in the presence of transforming growth factor-β1. Fibrocytes were first proposed as a mesenchymal cell type in PB that rapidly enters sites of tissue injury.63 They comprise 0.1% to 0.5% of TNCs in PB and express proteins characteristic of both fibroblasts and hematopoietic cells, such as collagen I, CD11b, CD13, CD34, CD45RO, MHC class II, and CD86.64 From these observations, at least 3 possibilities concerning the differentiation pathway from hematopoietic stem cells to hepatic stellate cells are considered: (i) hematopoietic stem cells directly home to injured liver; (ii) they differentiate into mature myeloid cells and migrate to the liver; or (iii) they give rise to fibroblast precursors, infiltrate into injured liver, and then transdifferentiate into hepatic stellate cells. Further studies that address this issue are currently underway.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (16590935 and 18591055 to M.M. and 19591106 to N.K.).

Authorship

Contribution: E.M., M.M., and N.K. designed research; E.M., M.M., S.Y., S.N., K.K., Y.S., T.S., K.Y., K.O., K.N., and F.I. performed research and analyzed data; M.M., H.S., and N.K. edited the manuscript; and E.M., M.M., and N.K. wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Masahiro Masuya or Naoyuki Katayama, Department of Hematology and Oncology, Mie University Graduate School of Medicine, 2-174 Edobashi, Tsu, Mie 514-8507, Japan; e-mail: mmasuya@clin.medic.mie-u.ac.jp or n-kata@clin.medic.mie-u.ac.jp.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal