Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are multipotent stem cells that can generate various microenvironment components in bone marrow, ensuring a precise control over self-renewal and multilineage differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells. Nevertheless, their spatiotemporal correlation with embryonic hematopoiesis remains rudimentary, particularly in relation to the human being. Here, we reported that human aorta-gonad-mesonephros (AGM) resided with bona fide MSCs. They were highly proliferative as fibroblastoid population bearing uniform surface markers (CD45−, CD34−, CD105+, CD73+, CD29+, and CD44+), expressed pluripotential molecules Oct-4 and Nanog, and clonally demonstrated trilineage differentiation capacity (osteocytes, chondrocytes, and adipocytes). The frequency and absolute number of MSCs in aorta plus surrounding mesenchyme (E26-E27) were 0.3% and 164, respectively. Moreover, they were functionally equivalent to MSCs from adult bone marrow, that is, supporting long-term hematopoiesis and suppressing T-lymphocyte proliferation in vitro. In comparison, the matching yolk sac contained bipotent mesenchymal precursors that propagated more slowly and failed to generate chondrocytes in vitro. Together with previous knowledge, we propose that a proportion of MSCs initially develop in human AGM prior to their emergence in embryonic circulation and fetal liver.

Introduction

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are defined as a group of multipotent stem cells that can functionally differentiate into at least bone, fat, and cartilage in vitro and in vivo.1,,,,,,–8 Under appropriate culture conditions, MSCs are readily amplified in vitro for several passages without signs of senescence and differentiation. The 2 properties render them as an intriguing source in cell therapy and tissue engineering. MSCs were first documented by Friedenstein et al at an extremely low frequency within the bone marrow (BM), a canonical reservoir for a variety of stem cells.1 Functionally, the self-renewal and differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are tightly and precisely regulated by the marrow stromal milieu, a complex cellular network composed of the descendents of MSCs. For example, osteoblasts lining the bone surface can modulate the HSC expansion via Notch signaling pathway or N-cadherin/β-catenin adherens complex in vitro and in vivo.9,10 The MSC, itself, can also modulate hematopoiesis in vitro through secreting a set of hematopoietic cytokines and intercellular contact.11,12 Systemic administration of adult or fetal tissue–derived MSCs promotes the homing and engraftment of HSCs in vivo by unknown mechanisms.13,,–16

Despite of our increasing understanding of MSCs in adult hematopoiesis, little is known about their developmental origin and correlation with strikingly changing blood-forming sites during embryogenesis, particularly in the human being.17 The first wave of hematopoiesis in humans is initiated during the third week in the extraembryonic yolk sac (YS), characterized by the production of nucleated erythrocytes in situ.18,19 As is the case in other higher vertebrates, the second wave is characterized by de novo generation of HSCs in the intraembryonic P-Sp/AGM, followed by migration and colonizing downstream fetal liver for further maturation and amplification.20,,–23 Campagnoli et al claim that human MSCs appear first in fetal blood at the seventh week, and later in the fetal liver and bone marrow from the 10th week.24 Recently, Mendes et al reported that the mesenchymal progenitors are exclusively allocated in the mouse AGM.25 However, the ontogeny of human MSCs in the embryonic hematopoietic tissues remains unknown.

Herein, we found that human AGM region served as a potent niche for embryonic MSCs that were roughly identical to the bone marrow regarding general morphology, immunophenotype, triple differentiation capacity, and immunobiologic feature. The expression of pluripotential-related markers (Oct-4 and Nanog) and the hematopoietic supportive activity in AGM-derived MSCs corroborated their development stage and anatomic location.

Methods

Human samples

Eighteen human embryos at 25 to 40 days of development were obtained immediately after voluntary terminations of pregnancy induced with the RU 486 antiprogestative compound. Human tissue collection for research purpose was approved by Research Ethics Committees of both Institute of Basic Medical Sciences and Air Force General Hospital. In all cases, pregnant women gave written consent for clinical procedure and research use of the embryonic tissues in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Developmental age was estimated according to several anatomic criteria as previously described.26

Isolation and culture of YS- and AGM-derived mesenchymal progenitor cells

The YS and AGM were sterilely dissected in cold PBS under the microscope as previously described.26 In some cases, the AGM was longitudinally subdissected, separating the dorsal aorta with its surrounding mesenchyme (AoM) from the urogenital ridges (UGRs). The tissues were digested for one hour at 37°C with 0.1% collagenase type I (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) in PBS containing 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS; StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC) followed by repeated passages through a 26-gauge needle. Then, the cell suspensions were plated at a density of 5000 cells/cm2 in α-MEM (Hyclone, Logan, UT) containing 10% FBS, 100 units/mL penicillin and 100 ng/mL streptomycin (Hyclone), and 5 ng/mL bFGF (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). After 48-hour incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2, nonadherent cells were removed by medium change. When approximately 70% to 80% confluence was reached, the adherent cells were digested with 0.25% trypsin/EDTA (Hyclone) for further expansion.

The growth kinetics was assessed by the cumulative population-doubling assay as previously described over 5 passages.27 The colony-forming unit of fibroblast (CFU-F) assay was carried out by plating cells at the density of 30 cells/well in 24-well plate. After 14 days of incubation, they were fixed with methanol followed by Wright-Giemsa staining.

Flow cytometry and immunofluorescence staining

For flow cytometry analysis, the adherent cells were harvested using 0.25% trypsin/EDTA, and stained for 30 minutes at 4°C with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated or phycoerythrin (PE)–conjugated monoclonal antibodies. Antibodies recognizing CD14, CD19, CD34, CD73, CD80, CD86, CD105, CD166, HLA-ABC, and HLA-DR were purchased from BD Biosciences PharMingen (Franklin Lakes, NJ). Antibodies against CD29 and CD44 were purchased from Biolegend (San Diego, CA), and antibody against CD31 was obtained from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). For immunofluorescence staining, experiments were performed according to the reagent protocols of rabbit anti-Oct4 (Chemicon, Temecula, CA) or goat anti-Nanog (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA).

Adipogenic, osteogenic, and chondrogenic differentiation assays

For adipogenic differentiation, the cultures were incubated in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 10−7 M dexamethasone, 0.5 μM isobutyl-methylxanthine, 10 ng/mL insulin, and 60 μM indomethacin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 2 weeks. Cells were then stained with fresh Oil-red-O solution (Sigma-Aldrich). For osteogenic differentiation, cells were incubated in DMEM with 10% FBS supplemented with 0.2 mM ascorbic acid, 10−7 M dexamethasone, and 10 mM β-glycerol phosphate (Sigma-Aldrich) for 2 to 3 weeks. The expression of alkaline phosphatase was analyzed using the staining kit (Sigma-Aldrich), and the mineralization capacity was evaluated by von Kossa staining. A micromass culture system was used to assess the chondrogenic differentiation. Cells (4 × 105) were placed in polypropylene tubes, centrifuged gently to form a micromass, and cultured in serum-free medium containing DMEM supplemented with 10−7 M dexamethasone, ITS+ (Sigma-Aldrich), 50 μg/mL ascorbic acid, 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Hyclone), 50 μg/mL proline (Sigma-Aldrich), and 20 ng/mL transforming growth factor-β3 (TGF-β3; R&D Systems). The medium was changed every 3 to 4 days. After 21 days, tissue aggregates were frozen, sectioned, and stained with Alcian blue, safranin O, and anti–collagen type II antibody (Chemicon) separately.

In vitro assay of hematopoietic supporting capacity

After irradiation (10 Gy), mesenchymal progenitor cells (MPCs) from adult BM, AGM, and YS were overlaid in 12-well plates to form confluent monolayers in long-term culture medium (StemCell Technologies). After 24 hours, 3 × 104 CD34+ cells, isolated from cord blood by CD34+ cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany), were added without any exogenous cytokines and cocultured at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 6 to 7 weeks. The medium was half-volume replaced weekly, and the nonadherent fraction was replated in methylcellulose-based colony-forming cell (CFC) assay system: 1% methylcellulose, 30% FBS, 10% BSA, 20 ng/mL granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), 20 ng/mL IL-3, 20 ng/mL IL-6, 20 ng/mL Tpo, 3 U/mL Epo, 10 ng/mL FL, and 50 ng/mL SCF. Epo was purchased from Kirin (Tokyo, Japan) and the other cytokines were obtained from Peprotech (London, United Kingdom). Alternatively, at the end of 7-week incubation, the bulk culture of long-term culture-initiating cells (LTC-ICs) was examined by quantifying the CFC according to the manufacturer's instruction (StemCell Technologies).

T-cell proliferation assay

Peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs) from different donors were isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque gradient separation. CD3+ cells were further purified from PBLs as responding cells using Pan T Cell Isolation Kit II (Miltenyi Biotec). The irradiated (10 Gy) PBLs were used as stimulators. Stimulators (105) and CD3+ cells (2 × 105) were added to each 96-well plate with or without confluent irradiated MSCs, and were pulsed with 1 μCi (0.037 MBq)/well 3H-thymidine (3H-TdR) during the last 12 hours of a 4-day coculture. Alternatively, 5 μg/mL phytohemagglutinin (PHA) was used as stimulator to induce T-cell proliferation. 3H-TdR incorporation was measured using Wallac Microbeta Trilux 1450-02P (Perkin Elmer, Wellesley, MA).

Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction analysis

Total RNA was collected using Trizol (Sigma-Aldrich). RNA was converted to cDNA and amplified according to the manufacturer's instructions. Then target genes were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with specific primers (Table S1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Phase contrast and fluorescence imaging

The images were collected using an Olympus CK2 inverted microscope (Tokyo, Japan) with 10×/0.25 NA A10PL objective and were acquired using a Nikon Coolpix 995 camera (Tokyo, Japan). Confocal images were collected by a Nikon TE300 inverted microscope (Tokyo, Japan) with a Nikon 20×/0.45 NA Plan Fluor objective lens and the Bio-Rad Radiance 2100 (Hercules, CA), and were acquired using a Bio-Rad LaserSharp 2000. Composite images were assembled in Adobe Photoshop version 7.0 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA).

Results

Morphology and growth kinetics of fibroblastoid adherent cells derived from human YS and AGM

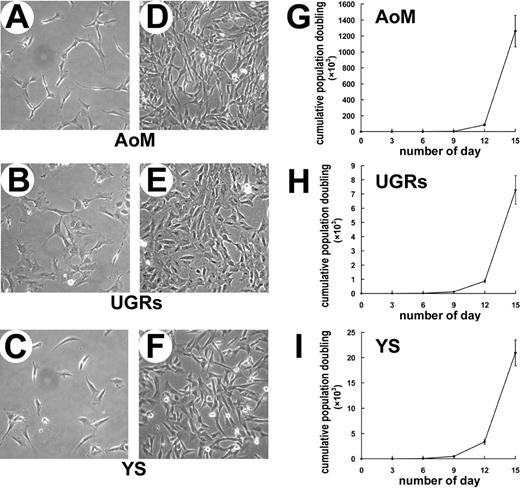

In the first step, the YS and AGM were separated from the human embryos. Single-cell suspensions were plated at a density of 5000 cells/cm2 in the medium identical to that used for culture of BM-derived MSCs. For embryos at the Carnegie stage 12 (21–29 somites, E26-E27), the viable cell number was 1.50 × 105 per YS and 1.03 × 105 per AGM. At the beginning, cells from both tissues could immediately attach to the well surface, and at least part of them was morphologically indistinguishable from the fibroblasts. After 3 passages, the fibroblastoid adherent cells (FACs) from AGM (data not shown) and YS (Figure 1C,F) became predominant and homogenous. In particular, when 80% to 90% of confluence was achieved, the cultures displayed a unique vortex shape as BM-derived MSCs. In an attempt to determine more precisely the distribution of FACs, the AGM was further subdissected longitudinally into its various components: AoM and UGRs. The FACs were found in the cultures of both AoM (Figure 1A,D) and UGRs (Figure 1B,E). The FACs were detected in the AGM and YS as early as day 25 of development, that is, shortly before the appearance of intra-aortic hematopoietic clusters at day 27 of gestation. It was interesting to find that many adipocytes appeared as soon as the YS cells were replated, indicating that adipogenesis might occur in the human YS. However, this was not the case in the AGM region.

Morphology and growth kinetics of fibroblastoid adherent cells (FACs) derived from human AoM, UGRs, and YS. Representative morphologies of FACs derived from AoM (A,D), UGRs (B,E), and YS (C,F) are shown at lower and higher densities. Cumulative population-doubling assay reveals that the FACs from AoM (G) proliferate more rapid than those from UGRs (H) and YS (I). Original magnification: (A-F) × 100. AoM indicates aorta with its surrounding mesenchyme; UGRs, urogenital ridges; and YS, yolk sac.

Morphology and growth kinetics of fibroblastoid adherent cells (FACs) derived from human AoM, UGRs, and YS. Representative morphologies of FACs derived from AoM (A,D), UGRs (B,E), and YS (C,F) are shown at lower and higher densities. Cumulative population-doubling assay reveals that the FACs from AoM (G) proliferate more rapid than those from UGRs (H) and YS (I). Original magnification: (A-F) × 100. AoM indicates aorta with its surrounding mesenchyme; UGRs, urogenital ridges; and YS, yolk sac.

Subsequent experiments were performed with the FACs of passage 3. The FACs derived from the AoM, UGRs, and YS were plated at the density of 10, 50, or 100 cells/cm2 and cultured for 10 days. The FACs from the 3 sites were readily expanded in vitro by successive trypsinization, seeding, and culture. The rates of expansion were sensitive to the initial plating densities, as visualized by the up-regulated growth rates corresponding to the decreased plating density (Figure S1). At the density of 10 cells/cm2, AoM-derived FACs achieved the highest increase in cell number (approximately 4000-fold), remarkably exceeding those from UGRs (700-fold) and YS (1100-fold; Figure S1). Then, the growth kinetics of the FACs were estimated by cumulative population-doubling assay over 5 passages. As expected, the FACs of AoM proliferated most rapidly with an accumulative population doubling of 1.3 × 106 (Figure 1G). Notwithstanding that the YS cells grew more rapidly than those from UGRs at the first several passages (Figure 1H,I), the growth rate of UGRs-derived FACs increased with passages and outnumbered that of YS cells (data not shown). The result indicated that human embryonic FACs could be expanded remarkably in vitro as MSCs, and a salient difference in proliferative potential also existed between distinct anatomic sites.

Molecular characterization of FACs in human YS and AGM region

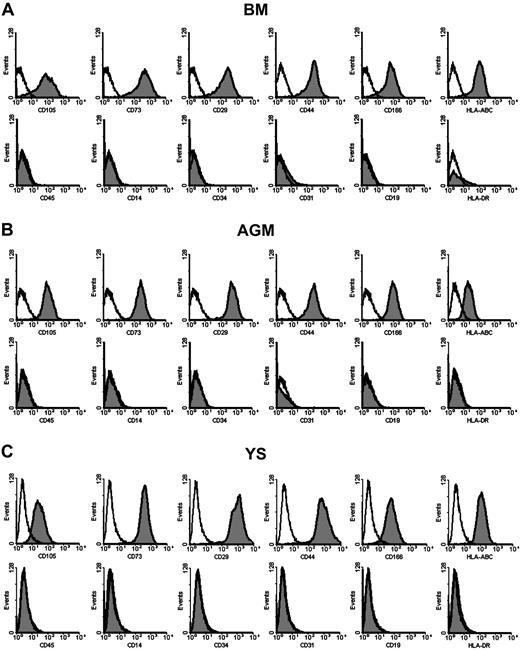

Flow cytometry was used to determine whether the morphologically homogenous FACs possessed uniform surface markers. As demonstrated in Figure 2, the culture-expanded FACs comprised a single phenotypic population after passage 3. As for the AGM, the FACs were found to be positive for CD105 (SH2), CD73 (SH3), CD29, CD44, CD166, and HLA-ABC (Figure 2B). In contrast, they were negative for CD45, CD14, CD19, CD34, and CD31, indicating their nonhematopoietic and nonendothelial identity. They were also negative for HLA-DR, resembling BM MSCs (Figure 2A). The FACs from YS, AoM, and UGRs were similar in immunophenotype (Figure 2C, and data not shown). At passage 10, the surface epitope profiles were consistent with those at earlier passages (data not shown).

Surface markers of FACs from human AGM and YS. Flow cytometric analysis shows that the immunophenotypes of FACs from AGM (B) and YS (C) are uniform and identical to those of BM-derived MSCs (A). They are positive for CD105 (SH2), CD73 (SH3), CD29, CD44, CD166, and HLA-ABC, and negative for CD45, CD14, CD34, CD31, CD19, and HLA-DR.

Surface markers of FACs from human AGM and YS. Flow cytometric analysis shows that the immunophenotypes of FACs from AGM (B) and YS (C) are uniform and identical to those of BM-derived MSCs (A). They are positive for CD105 (SH2), CD73 (SH3), CD29, CD44, CD166, and HLA-ABC, and negative for CD45, CD14, CD34, CD31, CD19, and HLA-DR.

Differentiation potential of the AGM- and YS-derived FACs

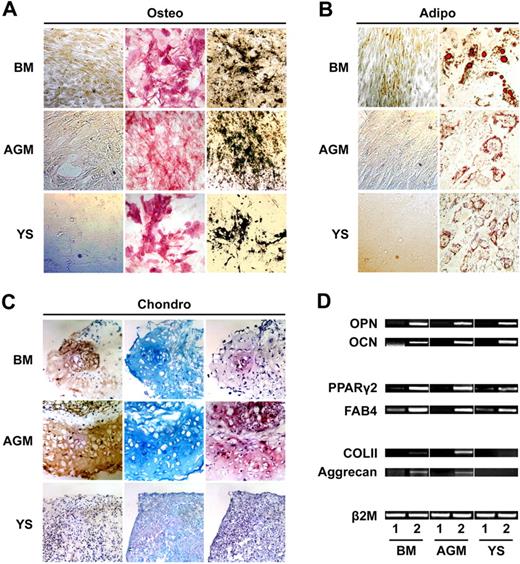

Functional test is necessary to justify the identity of MSCs. The FACs of passage 3 with homogenous morphology and phenotype from different tissues were then replated under conditions known to induce the differentiation of adult MSCs into osteogenic, adipogenic, and chondrogenic lineages. BM-derived MSCs were used as positive control.

When cultured in osteogenic-inductive medium with ascorbic acid, dexamethasone, and β-glycerol phosphate, the FACs underwent a dramatic change in cellular morphology from spindle shape to cuboidal, which was accompanied by an increased alkaline phosphatase activity (Figure 3A). Progressively, aggregates or nodules formed with calcium deposition as determined by von Kossa staining (Figure 3A). In addition, the substantial osteoblastic differentiation was shown by the mRNA expression of osteopontin (OPN) and osteocalcin (OCN; Figure 3D).

Mesenchymal potential of AGM- and YS-derived FACs. (A) FACs expanded from both AGM and YS can differentiate to osteoblasts with alkaline phosphatase activity (middle column) and mineral deposition (right column). Left column shows von Kossa staining of noninduced FACs. (B) Oil-red-O staining of noninduced FACs (left column) and induced adipocytes from FACs (right column) of BM, AGM, and YS. (C) Whereas AGM-derived FACs demonstrate chondrogenic potential, as shown by type II collagen immunostaining (left column), Alcian blue staining (middle column), and safranin O staining (right column), YS-derived FACs fail to generate chondrocytes in vitro. (D) The mRNA expression of genes specific for osteogenesis (osteopontin and osteocalcin), adipogenesis (PPARγ2 and FAB4), and chondrogenesis (COL II and aggrecan) are determined by RT-PCR. Lane 1 shows noninduced MPCs; lane 2, induced MPCs. PPARγ2 indicates peroxisome proliferation–activated receptor γ2; FAB4, fatty acid–binding protein 4; OPN, osteopontin; OCN, osteocalcin; and COL II, type II collagen. Original magnification: (A,B) ×100; (C) ×200.

Mesenchymal potential of AGM- and YS-derived FACs. (A) FACs expanded from both AGM and YS can differentiate to osteoblasts with alkaline phosphatase activity (middle column) and mineral deposition (right column). Left column shows von Kossa staining of noninduced FACs. (B) Oil-red-O staining of noninduced FACs (left column) and induced adipocytes from FACs (right column) of BM, AGM, and YS. (C) Whereas AGM-derived FACs demonstrate chondrogenic potential, as shown by type II collagen immunostaining (left column), Alcian blue staining (middle column), and safranin O staining (right column), YS-derived FACs fail to generate chondrocytes in vitro. (D) The mRNA expression of genes specific for osteogenesis (osteopontin and osteocalcin), adipogenesis (PPARγ2 and FAB4), and chondrogenesis (COL II and aggrecan) are determined by RT-PCR. Lane 1 shows noninduced MPCs; lane 2, induced MPCs. PPARγ2 indicates peroxisome proliferation–activated receptor γ2; FAB4, fatty acid–binding protein 4; OPN, osteopontin; OCN, osteocalcin; and COL II, type II collagen. Original magnification: (A,B) ×100; (C) ×200.

To assess the adipogenic differentiation potential, the FACs were plated at the density of 5000 cells/cm2 and cultured in medium that favored adipogenic differentiation. After 2 weeks of induction with dexamethasone, methyl-isobutylxanthine, and indomethacin, adipogenic induction was apparent by the accumulation of Oil-red-O staining lipid-rich vacuoles (Figure 3B). In complement to the results by histochemical analysis, the FACs after induction exhibited mRNA expression of peroxisome proliferation–activated receptor γ2 (PPARγ2) and fatty acid–binding protein 4 (FAB4), genes specific for adipocytes (Figure 3D).

To evaluate the chondrogenic potential, 4 × 105 FACs from AGM or YS were centrifuged gently in 15-mL polypropylene tube, and the cell pellets were cultured in the serum-free chondrogenic medium containing TGF-β3 for 3 weeks. Similar to BM-derived MSCs, the AGM-derived FACs formed pelleted micromass, developing a multilayered matrix-rich morphology. The chondrocyte-like lacunae were evident in histologic sections, and the extensive extracellular matrix was rich in type II collagen (Figure 3C), a typical marker of articular cartilage. Furthermore, the development and accumulation of cartilage matrix was shown by staining the proteoglycans with Alcian blue or safranin O (Figure 3C). Under the same chondro-inductive medium, the FACs from YS developed a smaller spherical micromass. However, the extracellular matrix was poor and failed to react with anti–type II collagen antibody, Alcian blue, and safranin O (Figure 3C). The results were consistent in 7 independent experiments, suggesting that the chondrogenic capacity of YS-derived FACs was absent in vitro. Consistently, the mRNA expression of type II collagen and aggrecan, specific genes of chondrogenesis, were detected in the differentiation cultures of AGM but not YS (Figure 3D).

Clonal identification of AGM-derived MSCs

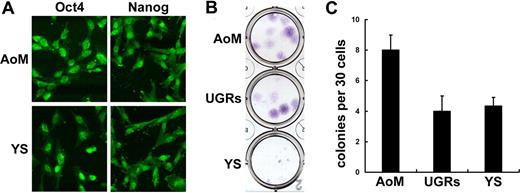

Oct-4 and Nanog are taken for specific markers of human and mouse embryonic stem cells (ESCs), and their expression has been reported in MSCs isolated from human first-trimester hematopoietic tissues.28 As shown in Figure 4A, both AoM- and YS-derived FACs homogenously expressed Oct-4 and Nanog. In a strict sense, stem cell identification must be undertaken at a clonal level. To confirm whether the FACs contained authentic MSC populations, clonal analysis of mesenchymal potential was performed. In the first step, the colony-forming potential of FACs was assessed by CFU-F assay. Thirty cells from YS, AoM, and UGRs (passage 3) were incubated in 24-well plate for 14 days, respectively. As demonstrated in Figure 4B, the CFU-F colonies from YS appeared smaller than those from AoM or UGRs. Representative data from 3 independent experiments showed that AoM-derived FACs possessed the highest colony-forming efficiency (26.7%), while that of UGRs (13.3%) and YS cells (14.4%) were much lower (Figure 4C).

Expression of pluripotent markers and colony-forming efficiency of embryonic FACs. Both AoM- and YS-derived FACs express Oct-4 and Nanog (A). CFU-F assay shows that AoM-derived FACs possess the highest colony-forming efficiency (26.7%), while those of UGRs (13.3%) and YS (14.4%) are much lower (B,C). Of note, colonies from YS are much smaller than those from AoM or UGRs. Original magnification: (A) ×200.

Expression of pluripotent markers and colony-forming efficiency of embryonic FACs. Both AoM- and YS-derived FACs express Oct-4 and Nanog (A). CFU-F assay shows that AoM-derived FACs possess the highest colony-forming efficiency (26.7%), while those of UGRs (13.3%) and YS (14.4%) are much lower (B,C). Of note, colonies from YS are much smaller than those from AoM or UGRs. Original magnification: (A) ×200.

Within the human AGM, AoM but not UGRs harbors hematopoietic potential, as assessed by development of myeloid and lymphoid cells.23 Thus, subsequent clonal differentiation experiments focused on the AoM. Eight well-circumscribed colonies were plucked by cloning cylinder. For differentiation experiments, individual AoM-derived colony was initially propagated for 3 passages, and the total cell number could mount to 5 × 105, which was enough for tripotential test (5 × 104 for adipogenesis or osteogenesis and 4 × 105 for chondrogenesis). As shown in Table 1, the expanded cells from 4 colonies could simultaneously generate adipocytes, osteocytes, and chondrocytes, while the remaining 4 failed to generate 1 or 2 mesenchymal lineages. As for YS, 2 of 4 individually propagated colonies displayed dual potential (Table 1). All of the data proved that the human AoM contained canonical MSCs with higher proliferation potential, while YS harbored bipotent or unipotent MPCs.

Mesenchymal potential of clonal-expanded cells from AoM and YS

| Clone number . | Differentiation potential . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Adipogenic . | Osteogenic . | Chondrogenic . | |

| AoM C1 | + | + | − |

| AoM C2 | + | + | + |

| AoM C3 | + | + | − |

| AoM C5 | + | − | − |

| AoM C6 | + | + | + |

| AoM C7 | + | + | + |

| AoM C8 | + | + | + |

| AoM C9 | + | + | − |

| YS C1 | + | − | ND |

| YS C2 | + | − | ND |

| YS C3 | + | + | ND |

| YS C4 | + | + | ND |

| Clone number . | Differentiation potential . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Adipogenic . | Osteogenic . | Chondrogenic . | |

| AoM C1 | + | + | − |

| AoM C2 | + | + | + |

| AoM C3 | + | + | − |

| AoM C5 | + | − | − |

| AoM C6 | + | + | + |

| AoM C7 | + | + | + |

| AoM C8 | + | + | + |

| AoM C9 | + | + | − |

| YS C1 | + | − | ND |

| YS C2 | + | − | ND |

| YS C3 | + | + | ND |

| YS C4 | + | + | ND |

AoM indicates dorsal aorta plus its surrounding mesenchyme; YS, yolk sac; and ND, not determined.

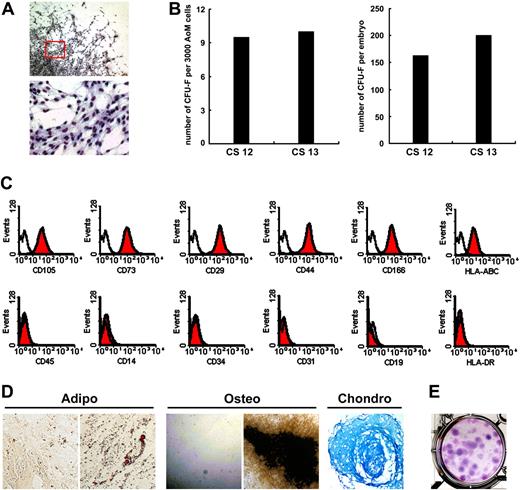

To further quantify the MSCs in the AoM subregion, we analyzed 5 embryos at the Carnegie stage 12 (n = 4, viable cell number: 5.15 × 104) or 13 (n = 1, viable cell number: 6.0 × 104). Primary AoM cells were plated at the density of 3000 cells per well of 6-well plate. After 10 days of incubation, 9.6 (range: 6–12) CFU-F colonies with typical morphology emerged (Figure 5A). As shown in Figure 5B, the total numbers of CFU-Fs were 164.2 (range: 116.6–213.4) and 200 in the AoM of CS 12 and CS 13 embryos, respectively. Clonally amplified cells also displayed homogenous surface markers (Figure 5C). Individually plucked CFU-F colonies (n = 4) could be easily propagated and all of them were capable of differentiating to adipocytes, osteocytes, and chondrocytes (Figure 5D). Furthermore, 2 individually expanded MSCs for 6 passages retained a high cloning efficiency of 29.3% and 30.0% (Figure 5E), which was similar to that of bulk-cultured AoM-MSCs (Figure 4C).

Frequency and absolute number of MSCs in the human AoM subregion. Three thousand primary AoM cells are incubated for 10 days, and on average 9.6 well-circumscribed CFU-F colonies emerge in the culture (A and left part of B). The total numbers of CFU-Fs are 164.2 and 200 in the AoM of embryos at CS 12 and CS 13, respectively (B right). Clonally amplified cells display homogenous surface markers (C). All of the individually plucked CFU-F colonies (n = 4) are capable of differentiating to adipocytes, osteocytes, and chondrocytes manifested by Oil-red-O, von Kossa, and Alcian blue staining, respectively (D). Noninduced cells stained by Oil-red-O and von Kossa are shown in the left (adipo and osteo in panel D). One representative of 2 individually expanded MSCs for 6 passages retains a cloning efficiency of 29.3% (E). CS indicates Carnegie stage. Original magnification: (A top) ×40; (A bottom) ×200; (D adipo and osteo) ×100; (D chondro) ×200.

Frequency and absolute number of MSCs in the human AoM subregion. Three thousand primary AoM cells are incubated for 10 days, and on average 9.6 well-circumscribed CFU-F colonies emerge in the culture (A and left part of B). The total numbers of CFU-Fs are 164.2 and 200 in the AoM of embryos at CS 12 and CS 13, respectively (B right). Clonally amplified cells display homogenous surface markers (C). All of the individually plucked CFU-F colonies (n = 4) are capable of differentiating to adipocytes, osteocytes, and chondrocytes manifested by Oil-red-O, von Kossa, and Alcian blue staining, respectively (D). Noninduced cells stained by Oil-red-O and von Kossa are shown in the left (adipo and osteo in panel D). One representative of 2 individually expanded MSCs for 6 passages retains a cloning efficiency of 29.3% (E). CS indicates Carnegie stage. Original magnification: (A top) ×40; (A bottom) ×200; (D adipo and osteo) ×100; (D chondro) ×200.

Previous finding documented the endothelial potential of mouse AGM-derived stromal cells.29 As shown in Figure S2, BM- and AoM-derived MSCs were able to generate capillary-like structures in Matrigel within 24 hours. Furthermore, a minority of the cells acquired the expression of CD34 and CD31, the relatively specific endothelial molecules that were absent in noninduced MSCs.

Embryonic MPCs supported hematopoiesis in vitro

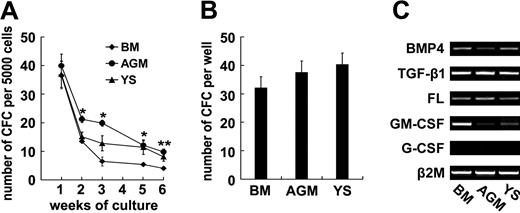

To determine whether MPCs isolated from human embryos were able to regulate hematopoiesis as do their adult counterparts, we performed in vitro long-term hematopoietic supporting assay. After irradiation (10 Gy), MPCs from BM, YS, and AGM were seeded in 12-well plates to form a confluent monolayer. Twenty-four hours later, human cord blood–derived CD34+ cells were overlaid and maintained in long-term culture medium for 6 to 7 weeks without adding any exogenous cytokines. According to a previously described method,24 weekly CFC assay was carried out on the nonadherent fraction from the culture. As shown in Figure 6A, the CFCs were continuously yielded for 6 weeks in the wells with AGM-, YS-, and BM-derived MPCs. On the contrary, the cultures in the wells without feeder layer failed to produce hematopoietic colonies after 1 week of incubation (data not shown). Statistical analysis representative of 3 independent experiments showed that the CFC frequencies in the AGM group exceeded those of BM at multiple time points (Figure 6A). Furthermore, the LTC-IC assay using bulk culture was carried out. After 7-week cocultures of CD34+ cells with MPCs, the CFCs in the cultures including the adherent layers were determined. As shown in Figure 6B, there were 37.5 (± 5.9) CFCs in the presence of AoM-MSCs, resembling those with BM-MSCs (32 ± 3.4, P > .05). RT-PCR assay showed that the AoM- and YS-derived MPCs expressed a set of early-acting hematopoietic cytokines including bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4), TGF-β1 and FL, and lineage-specific cytokine GM-CSF. Generally, the data indicated that human embryonic MPCs were capable of supporting long-term hematopoiesis in vitro.

Embryonic mesenchymal progenitor cells (MPCs) support long-term hematopoiesis in vitro. To determine whether embryonic MPCs are able to regulate hematopoiesis, weekly colony-forming cell (CFC) assay is carried out on the nonadherent fraction collected from the cocultures over 6 weeks. Statistical analysis of one representative from 3 independent experiments shows that the CFC frequencies in the AGM-MSC group exceed that of BM-MSCs at multiple time points (A). Furthermore, the LTC-IC assay using bulk culture is carried out 3 times. After 7-week incubation, the total CFCs in individual wells including the adherent layers are quantified. As shown in panel B, there are 37.5 (± 5.9) CFCs in the cultures with AGM-MSCs, resembling those with BM-MSCs (32 ± 3.4, P > .05). (C) RT-PCR assay shows that embryonic MPCs express a set of early-acting hematopoietic cytokines, including BMP4, TGF-β1, and FL, and all lineage-specific cytokine GM-CSFs (except G-CSF). The results are expressed as means (± SEM). Significance was determined using the Student t test: *P < .05; **P < .01, compared with the data of BM control.

Embryonic mesenchymal progenitor cells (MPCs) support long-term hematopoiesis in vitro. To determine whether embryonic MPCs are able to regulate hematopoiesis, weekly colony-forming cell (CFC) assay is carried out on the nonadherent fraction collected from the cocultures over 6 weeks. Statistical analysis of one representative from 3 independent experiments shows that the CFC frequencies in the AGM-MSC group exceed that of BM-MSCs at multiple time points (A). Furthermore, the LTC-IC assay using bulk culture is carried out 3 times. After 7-week incubation, the total CFCs in individual wells including the adherent layers are quantified. As shown in panel B, there are 37.5 (± 5.9) CFCs in the cultures with AGM-MSCs, resembling those with BM-MSCs (32 ± 3.4, P > .05). (C) RT-PCR assay shows that embryonic MPCs express a set of early-acting hematopoietic cytokines, including BMP4, TGF-β1, and FL, and all lineage-specific cytokine GM-CSFs (except G-CSF). The results are expressed as means (± SEM). Significance was determined using the Student t test: *P < .05; **P < .01, compared with the data of BM control.

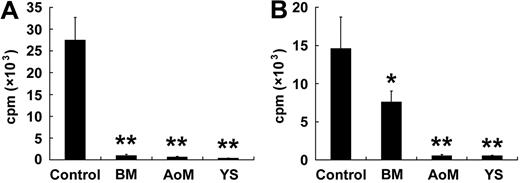

Embryonic MPCs were capable of suppressing T-lymphocyte proliferation in vitro

It has been well documented that human and murine MSCs can suppress T-lymphocyte proliferation in vitro when stimulated by nonspecific mitogens or allogeneic lymphocytes.30,31 To evaluate whether human embryonic MPCs possessed similar immunoregulatory function, lymphocyte transformation test and mixed leukocyte reactions (MLR) were carried out. Upon the stimulation of PHA (5 μg/mL), the CD3+ cells congregated into large clusters. Nevertheless, there were no or only very small clusters when the CD3+ cells were cocultured with BM-, AGM-, or YS-derived MPCs (data not shown). The results were also confirmed in 3 independent experiments by 3H-TdR incorporation assay at an MPCs/PBLs ratio of 1:10 (Figure 7A). Upon stimulation of allogeneic PBLs, the CD3+ cells presented a strong proliferation response at a mean incorporation of 14 605 (± 4137) cpm (Figure 7B). However, the effect was significantly inhibited by the addition of MPCs from BM (mean incorporation of 7595 ± 1425 cpm, P < .05), AoM (mean incorporation of 554 ± 171 cpm, P < .01), or YS (mean incorporation of 553 ± 33 cpm, P < .01). These data suggested that the MPCs with potent immunomodulatory capacity developed in human AGM and YS as they did in adult BM.

Embryonic MPCs are capable of suppressing T-lymphocyte proliferation in vitro. To evaluate whether embryonic MPCs possessed immunoregulatory function, lymphocyte transformation test and mixed leukocyte reactions (MLRs) are carried out. In the presence of MPCs of BM, AoM and YS origin, in vitro proliferation of CD3+ T lymphocytes stimulated by nonspecific mitogens (A) and allogeneic lymphocytes (B) is significantly suppressed. The results represent the means (± SEM) from 3 independent experiments. Significance is determined using the Student t test: *P < .05; **P < .01, compared with the control data.

Embryonic MPCs are capable of suppressing T-lymphocyte proliferation in vitro. To evaluate whether embryonic MPCs possessed immunoregulatory function, lymphocyte transformation test and mixed leukocyte reactions (MLRs) are carried out. In the presence of MPCs of BM, AoM and YS origin, in vitro proliferation of CD3+ T lymphocytes stimulated by nonspecific mitogens (A) and allogeneic lymphocytes (B) is significantly suppressed. The results represent the means (± SEM) from 3 independent experiments. Significance is determined using the Student t test: *P < .05; **P < .01, compared with the control data.

Discussion

In contrast to the increasing understandings of MSCs in adult bone marrow, little is known about the onset of such multipotent stem cells in mammalian embryos. In this study, authentic human MSCs are localized to one of the earliest blood-forming sites—the AGM. The MSCs within the unique structure were nearly indistinguishable from those in the fetal liver and adult bone marrow. In the culture, they grew rapidly with spindlelike morphology, generated macroscopic fibroblastic colonies efficiently, and clonally underwent trilineage commitment upon appropriate stimuli. Furthermore, they were neither hematopoietic (CD45−) nor endothelial (CD34−, CD31− and CD144−) cells, suggestive of a phenotypical divergence from the neighboring hemangioblastic compartment in the AGM. They were homogeneously positive for CD29, CD44, CD105, and CD73 even after 10 passages, and strongly expressed pluripotent stem cell markers (Oct-4 and Nanog) that are present in the MSCs within human fetal tissues other than adult BM.28

Current knowledge regarding hematopoietic supportive stroma in the mouse AGM region is based largely on investigations using transformed or nontransformed stromal cell lines within the vascular smooth muscle cell hierarchy.29,32,,,–36 Functional analysis reveals that none meets the criterion of bona fide MSCs and, in particular, the chondrogenic potential is not detected.29 Similarly, chondrogenic progenitors (0.85/104 cells) are present at a lower frequency than osteogenic (1.93/104 cells) or adipogenic (2.92/104 cells) progenitors in the mouse AGM,25 and a significant proportion of human AGM-MSCs lacked chondrogenic potential. Of note, the subregional difference regarding mesenchymal potential is more salient in mouse AGM than that of human beings.25 Whereas MPCs from mouse AoM have a more restricted potential (osteogenic and chondrogenic) than those from UGRs, the 2 parts of human embryos demonstrated similar trilineage potential (data not shown). The frequency of MPCs in the AGM remained almost constant in the mouse (E11 vs E12) and human being (E26-E27 vs E28-E29), but the absolute number increased slightly due to an amplification of total cell numbers. Unlike mouse, human AGM is not the exclusive site for MSC ontogeny because mesenchymal potential was detected in the somites and limb buds of human embryos at Carnegie stage 12 (E26-E27) (X.-Y.W. and N.M., unpublished data, October 2007). Thus, it will be instructive to determine whether the hematopoietic supportive and immunoregulatory potential of human embryonic MSCs are spatially regulated. Conceivably, the AGM serves as a major niche favorable for development of a variety of mesenchymal precursors in a successive hierarchy. For example, the mesoangioblasts, a type of mesodermal progenitors, have been isolated from mouse E9 dorsal aorta and are quite different from typical MSCs in several aspects.37 They amplify at the beginning only in the presence of embryonic fibroblastic feed layer, express endothelial-related markers such as Flk-1 and CD31, and are able to generate nearly all the mesodermal components (blood, bone, cartilage, and muscle). Further clarification is needed regarding whether the mesoangioblasts are the precursors of MSCs in the AGM region.

The dorsal aorta plus underlying mesenchyme prove to be the source of intraembryonic HSCs by in vitro and in vivo functional analysis.38,,–41 The marked asymmetry of dorsal aorta hematopoiesis suggests that the formation of intra-aortic hematopoietic clusters is not a stochastic event, but is more presumably determined by microenvironmental signals localized to the ventral wall of the aorta. Below the ventral aorta, a specific mesenchymal layer is composed of densely packed round cells that express neither hematopoietic nor endothelial markers but extracellular matrix proteins suggestive of stroma. Notwithstanding that a direct link between embryonic hematopoietic and stromal microenvironment has not been proven in vivo, availability of hematopoietic-supporting stromal cell lines undoubtedly provides valuable insights into such correlation. Cocultures of hematopoietic cells with some stromal clones (if not all) are capable of maintaining the long-term reconstitution activities, and the supportive properties of these stromal clones are largely retained even after being induced to mature osteoblasts in vitro.29 Most impressively, upon exposure to AGM-derived stromal cell line, the early YS-derived precursors are conferred with a capacity of long-term hematopoietic reconstitution.36 Indeed, human AGM-derived MSCs produced early-acting cytokines including BMP4, TGF-β1, and FL, consistent with their efficient support of long-term hematopoiesis in vitro. Conversely, the generation of mesenchymal progenitors is independent of HSC development. Whereas HSCs are defective in Runx-1−/− embryos, the frequency of mesenchymal progenitors in the mouse AGM is unaltered.25

Compared with the AGM, human YS-derived MPCs grew much more slowly, harbored a lower self-renewal efficiency, and failed to produce cartilage in vitro. However, further investigation should be carried out to verify their chondrogenic potential in vivo. The presence of mesenchymal progenitors in human YS is in striking contrast to that of the mouse, in which neither adipogenic nor osteogenic potential is detected.25 Notwithstanding that the YS is a simple endomesodermic anatomic structure, the roles of its cellular components in the induction and subsequent decline of human primitive hematopoiesis remain elusive. The endodermal or mesodermal endothelial-like cells are recognized for constituting the main niche for YS-specific hematopoietic activities, that is, driving macrophage differentiation with few granulocytes.42 Hence, the YS-derived MPCs may, together with endodermal and endothelial elements, form a more complex niche matching the extraembryonic hematopoiesis. Whether the mesenchymal potential in human YS is autonomously generated should be illustrated by collecting the tissue prior to the establishment of embryonic circulation at the third week of gestation. However, the external colonization of MPCs to the yolk sac appears unlikely in the mouse embryos. Despite the emergence of MPCs in the circulation at E12, the mesenchymal potential is absent in the YS at E14.25

During mammalian embryogenesis, hematopoiesis proceeds successively within distinct cellular microenvironments such as the YS blood island, AGM mesenchyme, hepatic parenchyme, and BM primary logette, reflecting a remarkable adaptation of the developing hematopoietic system to the rapidly changing niche.43,44 Taken together with the evidence illustrating the mesenchymal precursor development in blood-forming tissues of both human fetus and mouse midgestation embryos,24,25 we herein propose that a proportion of MSCs may arise initially in the AGM, undergo a transient migration in connected circulation, and colonize the fetal liver. A more comprehensive analysis is under way to compare the MSC populations at different developmental stages and allocations regarding their molecular profiles and hematoregulatory traits.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Dr Sheng Zhou for critical reading of the paper.

This study was supported by the National Key Basic Research Program of China (nos. 2005CB522705, 2005CB522605, and 2006CB943501), the National Natural Science Foundation (no. 30300181), and High-tech Research and Development Program of China (2006AA02Z168).

Authorship

Contribution: X.-Y.W. performed research, analyzed data, prepared figures, and wrote the paper; Y.L. performed research, analyzed data, and prepared figures; W.-Y.H. performed research and analyzed data; L.Z., H.-Y.Y., C.-M.H., Y.-L.L., G.Y., and X.-D.L. performed research; Y.T. and X.Y. designed research; B.L. designed research, analyzed data, prepared figures, and wrote the paper; N.M. designed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Ning Mao, Department of Cell Biology, Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, Tai Ping Road 27, Beijing 100850, China; e-mail: maoning@nic.bmi.ac.cn; or Bing Liu, Department of Cell Biology, Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, Tai Ping Road 27, Beijing 100850, China; e-mail: bingliu17@yahoo.com.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal