The retinoic acid receptor (RAR) α gene (RARA) encodes 2 major isoforms and mediates positive effects of all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) on myelomonocytic differentiation. Expression of the ATRA-inducible (RARα2) isoform increases with myelomonocytic differentiation and appears to be down-regulated in many acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cell lines. Here, we demonstrate that relative to normal myeloid stem/progenitor cells, RARα2 expression is dramatically reduced in primary AML blasts. Expression of the RARα1 isoform is also significantly reduced in primary AML cells, but not in AML cell lines. Although the promoters directing expression of RARα1 and RARα2 are respectively unmethylated and methylated in AML cell lines, these regulatory regions are unmethylated in all the AML patient cell samples analyzed. Moreover, in primary AML cells, histones associated with the RARα2 promoter possessed diminished levels of H3 acetylation and lysine 4 methylation. These results underscore the complexities of the mechanisms responsible for deregulation of gene expression in AML and support the notion that diminished RARA expression contributes to leukemogenesis.

Introduction

Despite progress in the understanding of the molecular abnormalities in acute myeloid leukemia (AML), overall survival rates remain low, reinforcing the need for more effective therapies.1 Among the subtypes of AML, acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL), which in most patients is associated with the translocation between the retinoic acid receptor (RAR) α (RARA) and PML genes, leading to expression of the PML-RARα fusion oncoprotein (other much less common rearrangements involving RARA have been described2 ), responds uniquely to differentiation therapy with all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA).3 Given that PML-RARα acts to inhibit the positive effects of physiological ATRA on regulation of gene expression and myelomonocytic differentiation, these dramatic therapeutic effects seemed at first paradoxical. However, progress in understanding the molecular mechanisms through which RARs and other nuclear receptors regulate gene expression, which involves ligand-mediated exchange of corepressor for coactivator4 and postactivation receptor degradation,5 provided a platform for understanding how administration of pharmacologic levels of ATRA can restore RARα signaling and differentiation in APL.6 Nevertheless, the molecular basis for the general lack of response of non-APL AML to ATRA remains poorly understood.

We have previously demonstrated that expression of the RARα2 isoform increases with differentiation of murine hematopoietic progenitors along the myelomonocytic lineage and that AML cell lines, including ATRA-resistant APL cells, do not express this isoform effectively.7,8 This lack of RARα2 expression and ATRA response may, at least in part, be a reflection of a general impairment of ATRA signaling, which may involve genetic factors and/or epigenetic mechanisms. To examine this hypothesis, we have evaluated in parallel expression of the RARA gene and DNA methylation of its promoters in normal hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells and primary AML blasts.

Methods

Primary cells and cell lines were maintained under standard conditions as previously described.7 Approval was obtained from the Multi-Center Research Ethics Committee (MREC) for Wales (United Kingdom); Erasmus Medical Center (Rotterdam, the Netherlands); and Montefiore Medical Center (Bronx, NY) institutional review boards for these studies based on strictly anonymous use of archived samples or informed consent obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Following approval from local Research Ethics Committees, AML bone marrows were taken with consent from anonymized patients at diagnosis. Umbilical cord blood samples from anonymized healthy full-term infants were obtained at the time of delivery, and peripheral blood samples from healthy adults were obtained by venipuncture. Mononuclear cells were separated by Ficoll (Biochrom, Berlin, Germany), and cells expressing CD11b, CD33, CD34, or CD133 were isolated with the corresponding magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA).

Results and discussion

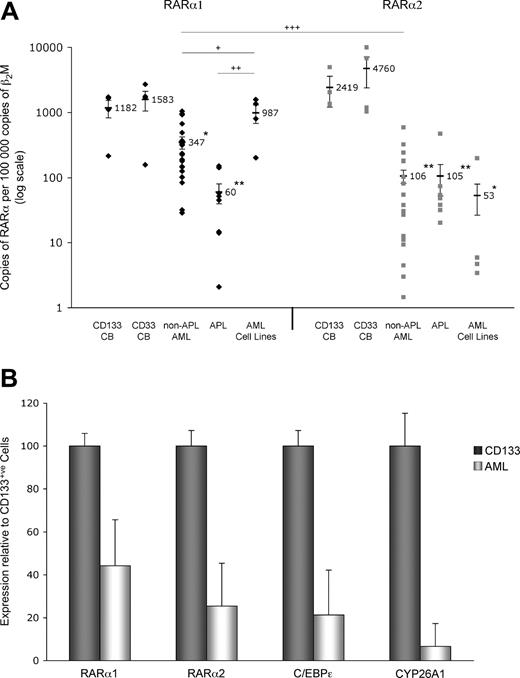

Given that ATRA signaling via RARA is required for optimal myelomonocytic differentiation of murine progenitor cells8,–10 and is disrupted by the PML-RARα fusion protein in APL,6 we sought to examine whether diminished RARA gene expression may be a general pathologic feature of AML. We compared by real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) the basal expression levels of the 2 major RARα isoforms in primary AML cells with AML cell lines and normal cord blood (CB)–derived human stem/progenitor cells (CD33+ or CD133+) and found that in primary non-APL AML and APL cells, the RARα1 copy numbers were 22% and 3.8%, respectively, of the value obtained for CD33+ CB cells (Figure 1A left panel). This contrasted with the value for AML cell lines, which was 62% of that for CD33+ CB cells. The diminution of RARα2 expression levels was even greater in primary non-APL AML (2.1%) and APL (1.9%) cells when compared with CD33+ CB cells (Figure 1A right panel). These values correlate with the data from AML cell lines, which showed a mean RARα2 copy number of 1.1% of that for CD33+ CB cells. Similar differences in RARα1 and α2 expression were observed relative to CD133+ CB cells; the mean values for RARα1 and α2 mRNA copy numbers in CD133+ CB cells were 1182 and 2418, respectively (Figure 1A). Although it is difficult to define what a good “normal” control is for AML cells, in this study we have used normal CB CD33+ and CD133+ progenitor/stem cells because AML blasts are usually CD33+ and most AML blasts are generally considered to derive from a primitive progenitor compartments. Additional analysis of the expression of 2 known ATRA target genes,11 CEBPE12 and CYP26A1,13 revealed that their mRNA levels are also diminished in patients with AML relative to those found in normal CD133+ cells, suggesting a causal relationship for deregulation of RARA and these downstream target genes (Figure 1B).

Expression of RARα2 is diminished in AML cell lines and patient samples, whereas RARα1 expression is significantly reduced only in patient samples. (A) RARα1 and RARα2 expression levels (♦ and ▩, respectively) were calculated by real-time RT-PCR. The samples analyzed were: CD133+ (n = 4) and CD33+ (n = 4) CB cells from healthy full-term infants; primary non-APL AML cells from consenting patients (n = 19; consisting of AML FAB subtypes M0, M1, M2, M4, and M5); primary APL cells (AML M3) from consenting patients (N = 8); and AML cell lines (n = 4; NB4 (APL), Kasumi-1, THP1 and U937). n indicates the number of individuals or cells lines. Indicated values refer to the mean; error bars, plus or minus SEM. Asterisks indicate significant differences from control and + symbols between the indicated cell populations (+/*P < .05; ++/**P < .01; +++/***P < .001). RNA isolation, cDNA preparation, and real-time PCR analysis were performed as previously described.7 RARα expression was normalized against the beta-2-microglobulin (β2M) housekeeping gene. For absolute quantification of RARα, PCR products were cloned into the pDrive vector (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), and the corresponding plasmid DNAs were used to generate standard curves. Negatives (nontemplate controls) were always included. Statistical analyses were performed as previously described.7 (B) RARα1, RARα2, C/EBPϵ, and CYP26A1 expression levels were calculated by real-time RT-PCR, except results for AML patient samples (n = 5) are shown relative to the values obtained for CD133+ CB cells. Pearson correlation coefficient reveals that RARα1 expression positively correlates with that of ATRA-responsive RARα2, C/EBPϵ, and CYP26A1 (r = .916, .877, and .748, respectively). The following PCR primers were used: C/EBPϵ-Fwd, 5′-GCTGTGGCGGTGAAGGAGGAG-3′ and C/EBPϵ-Rev, 5′-CAGGGGGGTGCGGCAGTGGC-3′; CYP26A1-Fwd, 5′-CGCATCGAGCAGAACATTCGC-3′ and CYP26A1-Rev, 5′-AAAGAGGAGTTCGGTTGAAGATT-3′. Statistical analyses were performed as previously described.7 Error bars represent SD.

Expression of RARα2 is diminished in AML cell lines and patient samples, whereas RARα1 expression is significantly reduced only in patient samples. (A) RARα1 and RARα2 expression levels (♦ and ▩, respectively) were calculated by real-time RT-PCR. The samples analyzed were: CD133+ (n = 4) and CD33+ (n = 4) CB cells from healthy full-term infants; primary non-APL AML cells from consenting patients (n = 19; consisting of AML FAB subtypes M0, M1, M2, M4, and M5); primary APL cells (AML M3) from consenting patients (N = 8); and AML cell lines (n = 4; NB4 (APL), Kasumi-1, THP1 and U937). n indicates the number of individuals or cells lines. Indicated values refer to the mean; error bars, plus or minus SEM. Asterisks indicate significant differences from control and + symbols between the indicated cell populations (+/*P < .05; ++/**P < .01; +++/***P < .001). RNA isolation, cDNA preparation, and real-time PCR analysis were performed as previously described.7 RARα expression was normalized against the beta-2-microglobulin (β2M) housekeeping gene. For absolute quantification of RARα, PCR products were cloned into the pDrive vector (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), and the corresponding plasmid DNAs were used to generate standard curves. Negatives (nontemplate controls) were always included. Statistical analyses were performed as previously described.7 (B) RARα1, RARα2, C/EBPϵ, and CYP26A1 expression levels were calculated by real-time RT-PCR, except results for AML patient samples (n = 5) are shown relative to the values obtained for CD133+ CB cells. Pearson correlation coefficient reveals that RARα1 expression positively correlates with that of ATRA-responsive RARα2, C/EBPϵ, and CYP26A1 (r = .916, .877, and .748, respectively). The following PCR primers were used: C/EBPϵ-Fwd, 5′-GCTGTGGCGGTGAAGGAGGAG-3′ and C/EBPϵ-Rev, 5′-CAGGGGGGTGCGGCAGTGGC-3′; CYP26A1-Fwd, 5′-CGCATCGAGCAGAACATTCGC-3′ and CYP26A1-Rev, 5′-AAAGAGGAGTTCGGTTGAAGATT-3′. Statistical analyses were performed as previously described.7 Error bars represent SD.

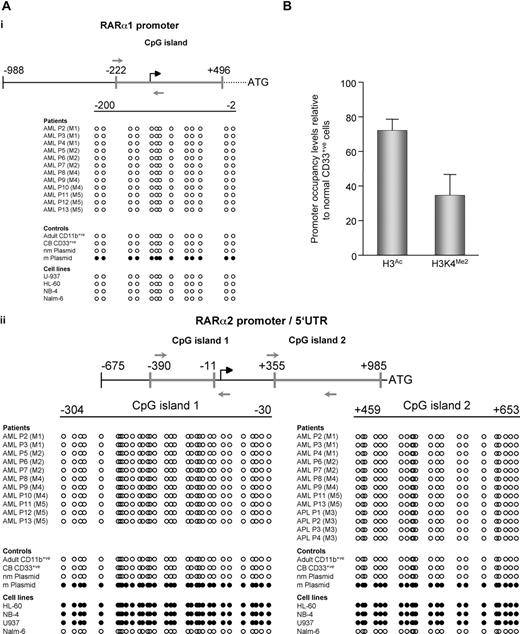

Epigenetic modifications, in particular aberrant promoter hypermethylation, are frequently associated with deregulation of gene expression in many tumor types.14 We therefore examined whether DNA methylation could account, at least in part, for the diminished RARα1 and/or RARα2 expression in AML. Sequencing of bisulphite-modified genomic DNA from AML cell lines revealed that while the RARα1 promoter was never methylated (Figure 2Ai), the CpG islands present in the RARα2 promoter and 5′ untranslated regions (5′ UTRs) were always hypermethylated (Figure 2Aii).

Mechanisms underlying loss of RARA expression differ between AML cell lines and patient samples. (A) RARα2 promoter is methylated in AML cell lines but not patient samples. Following bisulphite modification, specifically amplified PCR products were sequenced using primers (gray arrows) mapping to regulatory regions of (i) RARα1 or (ii) RARα2. CpG islands are indicated by heavy gray lines; all positions are shown relative to the transcription initiation sites (black broken arrows). Samples from patients, cell lines, and controls are indicated. nm indicates nonmethylated plasmid control; m, methylated plasmid control. Methylated CpG dinucleotides are represented by ●, and unmethylated CpGs are represented by ○. Sequencing revealed the RARα2 promoters of individual clones to be completely demethylated. All unmethylated samples were sequenced on both the sense and antisense strands, and no CpG hemimethylation was found. Methylation levels for RARα2 CpG island 1 from 3 bisulphite-modified APL patient samples were quantified by pyrosequencing,16 and a mean value of 3.7% methylated cytosine per CpG dinucleotide was observed. Bisulphite modification of genomic DNA was performed as previously described,17 and PCR primers were selected using the MethPrimer program18 : BS-RARA1-Fwd, 5′-GTTTTGGGTTTGAGGGAGGGAT-3′ and BS-RARA1-Rev 5′-AACTTTACCCRAAACCCCAAACTAA-3′; BS-RARA2#1-Fwd, 5′-GGTYGGAGTTATATATGATGT-3′ and BS-RARA2#1-Rev 5′-AATAATCCCRATATCCTCCCCTTAA-3′; BS-RARA2#2-Fwd, 5′-GTAGAGTTGGGGTGGGGG-3′ and BS-RARA2#2-Rev, 5′-CAAAATACAACRACTCCCCAAATCC-3′. 1 and 2 refer to RARα2 CpG islands 1 (promoter) and 2 (corresponds to 5′ UTR of RARα2), respectively. PCR was performed using the FastStart system (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) supplemented with GC-rich solution. PCR products were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis, recovered, and sequenced directly using the previously mentioned PCR primers. For NB4 and U937 cell line samples, recovered PCR products were cloned into the pDrive vector (Qiagen) and sequenced using M13 forward and reverse primers. (B) Chromatin associated with the RARα2 promoter in primary AML cells is characterized by reduced transcriptional competence. Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays with antibodies directed against acetyl-histone H3 or dimethyl-histone H3 lysine 4 (K4) were performed on CD33+ CB cells and samples from AML patients (n = 2; consisting of AML FAB subtypes M4 and M5). DNA obtained from the input or from immunoprecipitated DNA was analyzed by real-time PCR using primers mapping to the RARα2 promoter region. Results were quantified as a percentage of immunoprecipitated material relative to input DNA, and levels of H3 acetylation (H3Ac) and H3K4 dimethylation (H3K4Me2) are shown relative to CD33+ CB cells. As expected, an irrelevant antibody-negative control did not immunoprecipitate the target DNA sequence (data not shown). The following PCR primers were used: ChIP-RARα2-Fwd, 5′-GAGCTGCACAATGTCACACC-3′ and ChIP-RARα2-Rev, 5′-GGCTGAACTCTCGCTGAACT-3′. Error bars are SD.

Mechanisms underlying loss of RARA expression differ between AML cell lines and patient samples. (A) RARα2 promoter is methylated in AML cell lines but not patient samples. Following bisulphite modification, specifically amplified PCR products were sequenced using primers (gray arrows) mapping to regulatory regions of (i) RARα1 or (ii) RARα2. CpG islands are indicated by heavy gray lines; all positions are shown relative to the transcription initiation sites (black broken arrows). Samples from patients, cell lines, and controls are indicated. nm indicates nonmethylated plasmid control; m, methylated plasmid control. Methylated CpG dinucleotides are represented by ●, and unmethylated CpGs are represented by ○. Sequencing revealed the RARα2 promoters of individual clones to be completely demethylated. All unmethylated samples were sequenced on both the sense and antisense strands, and no CpG hemimethylation was found. Methylation levels for RARα2 CpG island 1 from 3 bisulphite-modified APL patient samples were quantified by pyrosequencing,16 and a mean value of 3.7% methylated cytosine per CpG dinucleotide was observed. Bisulphite modification of genomic DNA was performed as previously described,17 and PCR primers were selected using the MethPrimer program18 : BS-RARA1-Fwd, 5′-GTTTTGGGTTTGAGGGAGGGAT-3′ and BS-RARA1-Rev 5′-AACTTTACCCRAAACCCCAAACTAA-3′; BS-RARA2#1-Fwd, 5′-GGTYGGAGTTATATATGATGT-3′ and BS-RARA2#1-Rev 5′-AATAATCCCRATATCCTCCCCTTAA-3′; BS-RARA2#2-Fwd, 5′-GTAGAGTTGGGGTGGGGG-3′ and BS-RARA2#2-Rev, 5′-CAAAATACAACRACTCCCCAAATCC-3′. 1 and 2 refer to RARα2 CpG islands 1 (promoter) and 2 (corresponds to 5′ UTR of RARα2), respectively. PCR was performed using the FastStart system (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) supplemented with GC-rich solution. PCR products were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis, recovered, and sequenced directly using the previously mentioned PCR primers. For NB4 and U937 cell line samples, recovered PCR products were cloned into the pDrive vector (Qiagen) and sequenced using M13 forward and reverse primers. (B) Chromatin associated with the RARα2 promoter in primary AML cells is characterized by reduced transcriptional competence. Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays with antibodies directed against acetyl-histone H3 or dimethyl-histone H3 lysine 4 (K4) were performed on CD33+ CB cells and samples from AML patients (n = 2; consisting of AML FAB subtypes M4 and M5). DNA obtained from the input or from immunoprecipitated DNA was analyzed by real-time PCR using primers mapping to the RARα2 promoter region. Results were quantified as a percentage of immunoprecipitated material relative to input DNA, and levels of H3 acetylation (H3Ac) and H3K4 dimethylation (H3K4Me2) are shown relative to CD33+ CB cells. As expected, an irrelevant antibody-negative control did not immunoprecipitate the target DNA sequence (data not shown). The following PCR primers were used: ChIP-RARα2-Fwd, 5′-GAGCTGCACAATGTCACACC-3′ and ChIP-RARα2-Rev, 5′-GGCTGAACTCTCGCTGAACT-3′. Error bars are SD.

In order to investigate the mechanisms responsible for loss of RARA expression in primary AML cells, we examined methylation of the RARα1 promoter (Figure 2Ai) and RARα2 (Figure 2Aii) promoter and 5′ UTRs in APL and non-APL AML patient samples. Surprisingly, in contrast to the promoter methylation observed in AML cell lines, none of the AML (including APL) patient samples displayed methylation of CpGs in either the RARα1 promoter or RARα2 promoter/5′ UTR. We also analyzed expression of the human tumor antigen PRAME (PReferential Antigen MElanoma), which has been reported to repress ATRA signaling in cell lines and is frequently overexpressed in a variety of human cancers.15 Normal CD33+ CB cells did not express PRAME, and while the K562 cell line was positive, only 2 of 8 APL and 1 of 7 non-APL AML samples examined expressed PRAME (Figure S1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article); thus, PRAME could not be responsible for the repression of ATRA signaling in patients with AML. It is possible that DNA methylation-independent epigenetic events, such as loss of positively acting and/or acquisition of negatively acting histone modifications may play a role in the down-regulation of RARα2 expression in AML. Consistent with this notion, in AML patient samples containing sufficient numbers of cells for chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis we found that, relative to normal CD33+ cells, the RARα2 promoter was associated with diminished levels of histone H3 acetylation and dimethylation of lysine 4, which are markers of transcriptional competence19,20 (Figure 2B).

An important aspect of our findings is that RARA expression is strongly diminished in both APL and non-APL AML. These results are consistent with a model where, in APL, PML-RARα makes a specific contribution to this phenotype, while in non-APL AML subtypes, similar effects on the RARA gene expression result from PML-RARα–independent mechanisms. For example, a recent report indicates that AML1/ETO can also interfere with ATRA signaling.21 It is also worth noting that similar levels of RARα2 expression are observed in AML cell lines with or without PML-RARα (Figure 1A) and the RARα2 promoter is methylated in all the examined AML cell lines, indicating that methylation and silencing of the RARα2 promoter can occur in a PML-RARα–independent manner. Although PML-RARα has been shown to recruit DNA methyltransferases22 and MBD1,23 as well as other chromatin-modifying activities, our results demonstrate that in fresh APL blasts, DNA methylation is not associated with the loss of RARα2 expression.

A lack of consistent RARα2 promoter methylation in AML patient samples was recently reported by Chim et al.24 This study did not, however, compare RARα2 promoter (or RARα2 5′ UTR) methylation status with expression of the RARα2 isoform. The authors did report the RARα2 promoter to be methylated in 40% of patients with APL, but samples were analyzed by methylation-specific PCR without any indication of the extent of promoter methylation; this technique can provide false-positive results. Methylation of the RARβ2 promoter (a RARα2 paralog) in AML has also been studied by a number of different investigators, but the results of these studies have been somewhat contradictory in nature.21,22,25,–27 Moreover, RARB is not readily expressed in normal hematopoietic cells or required for proper hematopoiesis,9,28 and RARβ2 promoter methylation has no effect on patient survival.25 In fact, our data indicate that, in contrast to normal cells, RARβ2 is expressed in a fraction of AML samples (Figure S2). Therefore, RARA represents a more physiologically relevant target for the investigation of impaired ATRA signaling in AML. In this respect, it may be interesting to examine whether the level of RARA expression correlates with prognosis in these hematopoietic neoplasms.

Taken together, our data indicate that diminished expression of the RARA locus is characteristic of AML and may be relevant to its pathogenesis. Although it appears that demethylating agents such as decitabine do not act directly on RARs in patients with AML, this class of drugs is therapeutically active in AML and myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), and remains a target for research into combination therapy.29 The results of this study emphasize the need for a better understanding of the mechanisms that block ATRA signaling and gene expression in AML as well as for research into combinatorial therapies using epigenetic drugs that, by targeting multiple processes, may be most effective in reactivating ATRA-sensitive gene expression and differentiation of AML cells.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge support from the Leukemia Research Fund of Great Britain, the Samuel Waxman Cancer Research Foundation, and the Kay Kendall Leukemia Fund.

Authorship

Contribution: A.G., A.B., and A.Z. designed the research; A.G., A.B., K.P., and M.B.-C. performed the research; D.-C.Z, D.G., R.G., M.v.L, S.W., T.E., and G.H. contributed vital new reagents or analytical tools; A.G. and A.B. collected data; A.G., A.B., K.P., and A.Z. analyzed the data; and A.G., K.P., and A.Z. wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Arthur Zelent, Section of Haemato-Oncology, Institute of Cancer Research, Brookes Lawley Building, 15 Cotswold Road, Sutton, Surrey SM2 5NG, United Kingdom; e-mail: arthur.zelent@icr.ac.uk.

References

Author notes

A.G. and A.B. contributed equally to this study.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal