Abstract

Somatic hypermutation (SHM) features in a series of 1967 immunoglobulin heavy chain gene (IGH) rearrangements obtained from patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) were examined and compared with IGH sequences from non-CLL B cells available in public databases. SHM analysis was performed for all 1290 CLL sequences in this cohort with less than 100% identity to germ line. At the cohort level, SHM patterns were typical of a canonical SHM process. However, important differences emerged from the analysis of certain subgroups of CLL sequences defined by: (1) IGHV gene usage, (2) presence of stereotyped heavy chain complementarity-determining region 3 (HCDR3) sequences, and (3) mutational load. Recurrent, “stereotyped” amino acid changes occurred across the entire IGHV region in CLL subsets carrying stereotyped HCDR3 sequences, especially those expressing the IGHV3-21 and IGHV4-34 genes. These mutations are underrepresented among non-CLL sequences and thus can be considered as CLL-biased. Furthermore, it was shown that even a low level of mutations may be functionally relevant, given that stereotyped amino acid changes can be found in subsets of minimally mutated cases. The precise targeting and distinctive features of somatic hypermutation (SHM) in selected subgroups of CLL patients provide further evidence for selection by specific antigenic element(s).

Introduction

Developing B cells generate a vast repertoire of antibody specificities through somatic recombination of distinct variable (V), diversity (D) (heavy chain only), and joining (J) genes to form the variable domain exons of immunoglobulins (IG).1 Unlike heavy chain complementarity determining regions (HCDR) 1 and 2, which are entirely encoded by the IGHV gene, HCDR3 is created de novo by the VDJ recombination process.1 The skewing of diversity to the HCDR3 implies that HCDR3 sequences are the principal determinants of specificity, at least in the primary repertoire.2,3 However, HCDR3 diversity is not enough to realize the full potential of antibody diversity.4 Furthermore, unconventional antigens, such as B-cell superantigens, may be recognized not via the CDRs but rather via the framework regions (FRs).5

Somatic hypermutation (SHM) of IG variable genes forms a second round of diversification after somatic recombination which increases antibody diversity.6 SHM has long been thought to occur mainly in the germinal centers (GCs) after antigen stimulation and in a manner dependent on T-cell help.7 Recent reports, however, suggest that SHM can be T-cell independent and may also occur outside classic GCs.8-13

In recent years, the mutational status of IGHV genes has been established as one of the most important molecular genetic markers in defining prognostic subgroups of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). CLL patients who carry IGHV genes with 98% identity or more to the closest germ line gene (“unmutated”) follow a more aggressive clinical course and have strikingly shorter survival than patients carrying IGHV genes with less than 98% identity to germ line (“mutated”).14,15 The 98% cutoff was chosen as a shortcut to exclude potential polymorphic variants16-19 and has been used by the majority of studies to make the clinically relevant distinction between “mutated” and “unmutated” cases. Initially, it was assumed that CLL cells expressing unmutated IGHV genes derived from naive B cells. Nevertheless, it was subsequently demonstrated that all CLL cells, irrespective of IGHV gene mutation status, have a surface phenotype typical of antigen-experienced B cells and show gene expression profiles similar to memory B cells.14,20-23

The CLL IG repertoire is characterized by overrepresentation of selected IGHV genes, in particular IGHV1-69, IGHV4-34, IGHV3-7, and IGHV3-21, although their relative frequencies vary between cohorts.14,24-27 SHM does not appear to occur uniformly among IGHV genes: for example, the IGHV1-69 gene is consistently reported to carry very few mutations as opposed to the IGHV3-7, IGHV3-23, and IGHV4-34 genes, which typically show a high load of mutations.14,24-27

Recently, multiple CLL subsets with distinctive IG heavy and light chain gene rearrangements were characterized and found to have remarkably stereotyped HCDR3 sequences within their B-cell receptors (BCRs).27-34 The expression of stereotyped BCRs was reported as significantly more frequent among CLL patients with unmutated versus mutated IGHV genes.32,34 CLL cases expressing stereotyped BCRs may also share unique molecular and clinical features, suggesting that a particular antigen-binding site can make a difference in terms of clinical presentation and possibly prognosis.30,34 For instance, the IGHV3-21/IGLV3-21 subset should be regarded as unfavorable whatever the degree of mutation,35 whereas the IGHV4-34/IGKV2-30 subset seems to be associated with an indolent course of the disease.34,36

Shared replacement mutations (“stereotyped” amino acid changes) at particular codon positions have been reported for a few subsets.34,37 These selective hypermutations may thus be interpreted as further evidence of antigen selection in CLL. That notwithstanding, relatively little is known about the pattern of SHM in CLL using certain IGHV genes or in subsets with stereotyped BCRs, in relation to that of B cells from healthy persons or patients with autoreactive diseases.

In this study, we examined the IGHV/IGHD/IGHJ rearrangements of 1939 patients with CLL and compared them with a large panel of IGH sequences from various types of normal and autoreactive B cells available in public databases. We demonstrate striking repertoire biases and HCDR3 features in unmutated or minimally mutated sequences, suggesting that, at least in some cases, the lack of mutations could be interpreted in the context of antigenic pressure to maintain the BCR in a germ line state. Whereas SHM patterns were, for the most part, typical of a canonical SHM process, we report that groups of CLL cases expressing the IGHV3-21 and IGHV4-34 genes exhibit unique SHM patterns. Remarkably, we also demonstrate that recurrent, “stereotyped” amino acid changes may often be evident across the entire IGHV gene sequence of patients with CLL expressing mutated BCRs with stereotyped HCDR3 sequences, even among minimally mutated cases.

Methods

Patient group

A total of 1939 patients with CLL from collaborating institutions in Finland (n = 33), France (n = 756), Greece (n = 452), Italy (n = 178), Spain (n = 59), and Sweden (n = 461) were studied for IGHV repertoire and mutational status. All cases displayed the typical CLL immunophenotype as described earlier25,27 and met the diagnostic criteria of the National Cancer Institute Working Group.38 Written informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the study was approved by the local Ethics Review Committee of each institution.

PCR amplification of CLL IGH rearrangements

In the majority of cases (1797 of 1939 cases; 93%), peripheral blood samples were analyzed; bone marrow (105 cases), lymph nodes (28 cases), and spleen specimens (9 cases) were also analyzed. Amplification and sequence analysis of IGH rearrangements were performed on either DNA or cDNA as previously described25,27,34,37 or using the BIOMED-2 protocol.39 Sequence data were analyzed using the IMGT database and tools.40,41 All sequences were in-frame; any partial sequences that did not include the entire HCDR1 were excluded from the analysis.

Collection of non-CLL sequence data

Non-CLL IGH sequences were retrieved from the IMGT/LIGM-DB database in August 2006. Stringent criteria were followed so that redundant, poorly annotated, out-of-frame, incomplete, or clonally related sequences were excluded from the analysis. The non-CLL cohort was intentionally diverse to offer the opportunity for comparisons with various types of B cells. The final collection of 5303 unique IGHV-D-J sequences included: (1) 447 sequences from B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders, (2) 3235 sequences from normal B cells, (3) 499 sequences from “immune dysregulation” disorders (allergy, asthma, various types of immunodeficiency), and (4) 1122 sequences from autoreactive cells (Table S1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Sequence analysis and data mining

Both CLL and non-CLL sequence sets were submitted to the IMGT V-QUEST analysis software41 to obtain gene and allele usage and mutation data. The following information was extracted:

IGHV gene usage, percentage of identity to germ line, and HCDR3 length: Output data from IMGT V-QUEST for both CLL and non-CLL sequence sets were parsed, reorganized, and exported to a spreadsheet through the use of computer programming with the Perl programming language. IGHV, IGHD, and IGHJ gene usage, allele usage, percentage of identity to germ line, and the HCDR3 length were recorded for each sequence.

Somatic hypermutation characteristics: Each nucleotide mutation in every sequence was recorded, as was the change or preservation of the corresponding amino acid, identified as replacement (R) or silent (S), respectively. Amino acids were grouped into one of 5 categories, compiled according to standardized biochemical criteria42 and based on physicochemical properties (hydropathy, volume, chemical characteristics)43 : (1) nonpolar/aliphatic: G, A, P, V, L, I, M; (2) polar, uncharged: S, T, C, N, Q; (3) basic: K, R, H; (4) acidic: E, D; (5) aromatic: F, Y, W.

To account for the fact that a mutation is more likely to occur in a heavy chain framework region (HFR) than a HCDR simply because of its greater length, each mutation was weighted, or normalized, by the codon length of the region in which it occurred; for example, an amino acid mutation in a HCDR1 of length 8 would be assigned a weight of 1/8, or 0.13. Subsequently, to compare mutation distributions between groups (eg, IGHV genes, subsets), the sum of the normalized mutation counts per HFR/HCDR was expressed as a percentage of the total normalized mutation counts in the group. We describe these values as the normalized distribution percentages throughout “Results.” Consequently, it was possible to compare mutation data (eg, total mutations/R mutations/S mutations) per region (eg, HCDR2, HFR3) or combinations of regions (HCDR1 and HCDR2), within/across different groupings of sequences (eg, individual IGHV genes, homologous subsets, and CLL vs non-CLL sequences).

We extracted additional information on all amino acid changes codon by codon and examined whether the somatically introduced amino acid belonged to the same biochemical category as the mutating amino acid (“conservative” change) or not (“nonconservative” change).

Hotspot targeting: Mutated sequences were also analyzed for targeting to the tetranucleotide (4-NTP) motifs RGYW/WRCY (R = A/G, Y = C/T, and W = A/T)44 and DGYW/WRCH (D = A/G/T, H = T/C/A).45 To account for differences in germ line composition, counts were normalized by evaluating the number of 4-NTP mutations per HCDR/HFR nucleotide length per 4-NTP position for each sequence.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics for discrete parameters included counts and frequency distributions. For quantitative variables, statistical measures included means, medians, standard deviations, and ranges. Significance of bivariate relationships between factors was assessed with the use of χ2 and Fisher exact tests. For all comparisons, a significance level of P = .05 was set and all statistical analyses were performed with the use of the Statistical Package SPSS, version 12.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

Results

IGHV repertoire and mutation status

A total of 1967 in-frame IGHV-D-J sequences obtained from 1939 CLL patients were included in the analysis; 28 patients carried double in-frame rearrangements. Overall, this large and geographically diverse series confirmed previously published IGHV repertoire data obtained in smaller series24-27,33 (Table S2).

Following the 98% identity cutoff value, which is used to make the clinically relevant distinction between “mutated” and “unmutated” CLL cases,15-19 1064 of 1967 sequences (54%) from our series were defined as “mutated,” whereas the remainder (903 of 1967 sequences, 46%) had “unmutated” IGHV genes. Of note, concordant mutational status was observed in both IGHV-D-J rearrangements in 15 of 28 cases with double in-frame rearrangements; in the remaining 13 cases, the 2 rearrangements had different mutational status.

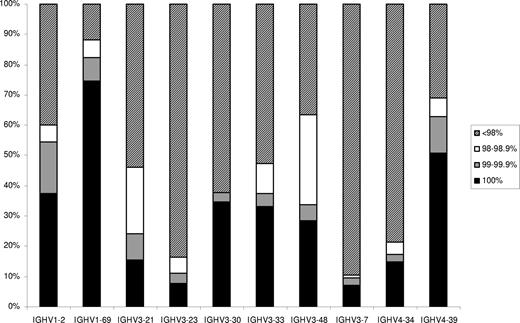

We subdivided “unmutated” sequences into a “truly unmutated” subgroup, which included 677 of 1967 sequences (34.4%) with IGHV genes in germ line configuration (100% identity), a “minimally mutated” subgroup, which included 133 of 1967 sequences (6.8%) with 99% to 99.9% identity to germ line, and a “borderline mutated” subgroup, which included 93 of 1967 sequences (4.7%) with 98% to 98.9% identity to germ line. The IGHV repertoires of the “mutated,” “minimally mutated,” “borderline mutated,” and “truly unmutated” subgroups differed (Table S3), in keeping with previous reports.24-27,33 At the individual gene level, the distribution of rearrangements of IGHV genes according to mutation status varied significantly (Figure 1; Table S4). In particular, the IGHV1-69 and IGHV1-2 genes predominated among, respectively, “truly unmutated” and “minimally mutated” sequences. In contrast, other IGHV genes were mostly used in “mutated” (< 98% identity) rearrangements (eg, IGHV4-34, IGHV3-23, IGHV3-7). Finally, the IGHV3-21 and IGHV3-48 genes had the highest proportion of “borderline mutated” (98%-98.9% identity) rearrangements. Significant differences were also observed with regard to mutation status among groups of sequences using different alleles39 of certain IGHV genes, in particular IGHV1-69, IGHV4-39, and IGHV3-30 (Table S5).

Distribution of rearrangements of the 10 most frequent IGHV genes of the present series according to mutational status.

Distribution of rearrangements of the 10 most frequent IGHV genes of the present series according to mutational status.

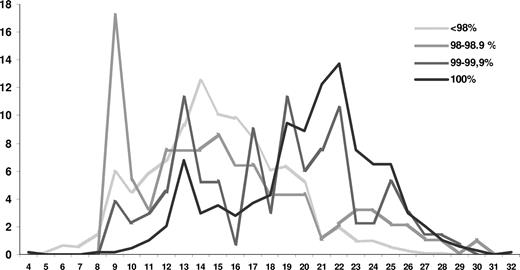

“Truly unmutated” sequences had significantly longer HCDR3s (median, 21 amino acids; range, 4-32 amino acids) than all other sequences; a significant difference in HCDR3 length was also observed among “minimally mutated” (median, 19 amino acids; range, 9-29 amino acids) and “borderline mutated” or “mutated” sequences (median, 15 amino acids for both groups; range, 9-30 amino acids; Figure 2; P < .001 for all comparisons).

Distribution of HCDR3 lengths according to mutational status. The striking peak at codon length 9 is predominantly comprised of IGHV3-21 subset 2 cases, which carry a distinctively short, stereotyped HCDR3.

Distribution of HCDR3 lengths according to mutational status. The striking peak at codon length 9 is predominantly comprised of IGHV3-21 subset 2 cases, which carry a distinctively short, stereotyped HCDR3.

Targeting of somatic hypermutation

Nucleotide substitution analysis was performed for all CLL sequences of the present series with less than 100% identity to germ line. Of the 18 149 mutations analyzed, transitions predominated (10 219 of 18 149, or 56.3%), in keeping with a canonical SHM process. However, at the level of individual IGHV genes, IGHV3-21 rearrangements showed distinctive features. In particular, compared with all other IGHV3 subgroup genes, IGHV3-21 rearrangements showed: (1) significantly fewer G-to-A substitutions (12.6% vs 17.2%; P < .01) and (2) significantly more T-to-A substitutions (14% vs 7.8%; P < .001). As revealed by comparison to non-CLL IGHV3-21 sequences, the overrepresentation of the T-to-A substitution was “IGHV3-21/CLL-biased.”

SHM frequencies in the HFRs and HCDRs were calculated for all IGHV subgroups. Here, as in all analyses, the normalized distribution percentages (as described in “Methods”) were used. Examination of the 3 largest IGHV subgroups (IGHV1/3/4) revealed markedly different SHM targeting. Overall, there was a greater targeting of R mutations to the HCDRs (especially HCDR2) of IGHV3 sequences compared with IGHV1 and IGHV4 sequences (Table S6). At the level of individual genes of the IGHV1/3/4 subgroups, the highest normalized R/S mutation ratios in HCDRs were observed among sequences using the IGHV4-59, IGHV3-15, IGHV4-4, IGHV3-21, and IGHV3-33 genes. In contrast, the lowest R/S mutation ratios in HCDRs were seen among IGHV4-39, IGHV4-34, and IGHV3-48 sequences (Tables S7,S8).

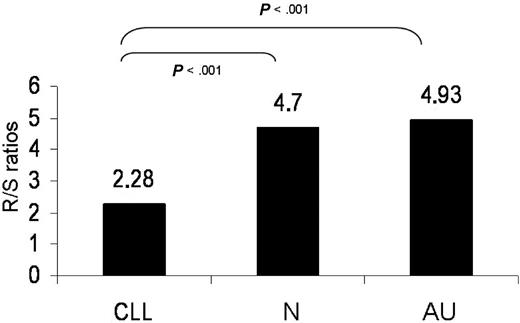

In particular, within the HCDR2, IGHV3-21 sequences had the highest R mutation targeting and the lowest S mutation targeting relative to all other genes. IGHV3-21 sequences also carried the lowest R mutation frequencies in all 3 FRs. Conversely, IGHV4-34 sequences displayed the lowest R mutation frequency as well as the lowest R/S mutation ratio in HCDR2. As revealed by comparison with IGHV4-34 sequences from normal and autoreactive cells, the paucity of R mutations in HCDR2 is a “CLL-biased” feature (Figure 3).

R/S normalized mutation ratios in the HCDR2 of rearrangements using the IGHV4-34 gene. Statistically significant differences were observed between CLL versus normal (N) or autoreactive (AU) clones.

R/S normalized mutation ratios in the HCDR2 of rearrangements using the IGHV4-34 gene. Statistically significant differences were observed between CLL versus normal (N) or autoreactive (AU) clones.

A significantly higher clustering of R mutations to 4-NTP motifs in the HCDR2 was observed among IGHV3- versus IGHV1- or IGHV4-expressing sequences (P < .01). A significant bias for R mutation targeting to 4-NTPs was also evident in HFR3 of IGHV4-expressing sequences, as exemplified by markedly different targeting for amino acid changes of 2 consecutive, alternative, serine codons. In particular, the AGC codon (“the hottest of SHM hotspots”46,47 ) at IMGT/HFR3-92 carried an amino acid change in 59% of mutated IGHV4 sequences, whereas the TCT codon at position IMGT/HFR3-93 carried an amino acid change in only 4% of sequences. Of note, the targeting of the AGC serine codon at IMGT/HFR3-92 was significantly higher in CLL versus normal vs autoreactive IGHV4 sequences (59% vs 39% vs 23.6%; P < .05).

Recurrent amino acid changes in subsets of CLL cases expressing stereotyped HCDR3 sequences

Analysis of sequences from the present series following previously described criteria34 allowed us to identify 530 of 1967 sequences (26.9%) as belonging to 110 different subsets with stereo-typed HCDR3 (Table S9), of which 48 have been reported previously27-34 ; each subset included from 2 up to 56 cases. The frequency of sequences carrying a stereotyped HCDR3 was significantly higher among “truly unmutated” or “minimally mutated” (43.4% and 36.7%, respectively) versus “borderline mutated” (24.7%) versus “mutated” (15.5%) sequences (P < .001 for all comparisons).

Shared (“stereotyped”) amino acid changes (ie, the same amino acid replacement at the same position) across the whole IGHV gene sequence were identified for subsets of CLL sequences with stereotyped HCDR3s. As revealed by comparison of the CLL versus non-CLL datasets, certain amino acid changes could be considered as “CLL-biased.” Furthermore, for certain IGHV genes, many stereotyped amino acid changes occurred significantly more frequently in cases with stereotyped rather than heterogeneous HCDR3 sequences and, therefore, could be considered as “subset-biased” (Table 1). A comprehensive list of such stereotyped amino acid changes is provided in Table S10. The most striking “CLL-biased” hypermutations were observed in the following subsets of sequences with stereotyped HCDR3s:

Nineteen sequences from the present series using allele *02 of the IGHV1-2 gene belonged to 2 subsets with stereotyped HCDR3s.32-34 The first subset (subset 1) included 53 minimally mutated/truly unmutated sequences, which used IGHV genes of the same clan (IGHV1-2/IGHV1-3/IGHV1-18, IGHV5-a, IGHV7-4-1). Among 15 IGHV1-2*02-expressing sequences of this subset, 9 had 100% identity to germ line, whereas 6 were found to carry a single replacement mutation, leading to a W-to-R change at IMGT/HFR2-55 (Figure 4A). The second subset (subset 28) included 5 IGHV1-2 sequences with stereotyped HCDR3s of which one used allele *01 and had 100% identity to germ line, whereas 4 used allele *02, as previously described,33,34 and carried the same single replacement mutation as described for subset 1. Comparison of “subset” IGHV1-2*02 sequences with CLL IGHV1-2*02 sequences with heterogeneous HCDR3 or non-CLL IGHV1-2*02 sequences demonstrated that the W-to-R change was “subset-biased.” In 2 cases of this subset, germ line sequence analysis of the IGHV1-2 gene confirmed that the W-to-R change was generated somatically and, thus, did not represent a polymorphism.

Fifty-six IGHV3-21 sequences with stereotyped HCDR3s belonged to subset 2.27,29,32-34 In this subset, 4 different recurrent mutations were observed at a frequency of 15% to 32% (Figure 4B). Comparison of CLL IGHV3-21 sequences with heterogeneous HCDR3s or non-CLL IGHV3-21 sequences demonstrated that amino acid changes3,4 were “subset-biased” (Table 1). Remarkably, within CLL, subset 2 cases had a higher targeting of the HCDR2 than non-subset 2 IGHV3-21 cases (Table S11).

Among a group of 27 IGHV4-34 sequences with stereotyped HCDR3s, which belonged to 2 different subsets (subset 4, subset 16),32-34,36 4 different recurrent mutations were observed at a frequency of 35% to 100% (Figures 4C,D). Noticeably, comparison to CLL IGHV4-34 sequences with heterogeneous HCDR3 or non-CLL IGHV4-34 sequences demonstrated that 3 of the 4 stereotyped amino acid changes were “subset-biased” (Table 1). Similar to subset 2, subset 4 and subset 16 sequences also showed distinctive SHM distribution “profiles” in the HCDRs/HFRs compared with IGHV4-34 sequences with heterogeneous HCDR3s. In particular, subset 4 IGHV4-34 sequences displayed a notably higher targeting of HFR2 and HCDR1 than IGHV4-34 sequences with heterogeneous HCDR3s; subset 16 cases also demonstrated a notably higher targeting of the HCDR1 than IGHV4-34 sequences with heterogeneous HCDR3s (Table S11).

Among a subset of 4 IGHV4-4-expressing sequences with stereotyped HCDR3s (subset 14),34 6 different recurrent mutations were observed in 75% to 100% cases (Figure 4E). Comparison of CLL IGHV4-4 sequences with heterogeneous HCDR3s or non-CLL IGHV4-4 sequences demonstrated that all the above-mentioned amino acid changes were “subset-biased” (Table 1).

“Stereotyped” amino acid changes

| Sequences . | Change . | CLL subset, n/N . | CLL heterogeneous, n/N . | Non-CLL, n/N . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IGHV1-2*02 sequences: IMGT-HFR2, codon 55 | W to R | Subset 1: 6/15 | 0/30 | 17/119 |

| IGHV1-2*02 sequences: IMGT-HFR2, codon 55 | W to R | Subset 28: 4/4 | 0/30 | 17/119 |

| IGHV3-21 sequences | Subset 2 | |||

| IMGT-HCDR1, codon 32 | S to T* | 11/56 | 6/29 | 12/95 |

| IMGT-HCDR1, codon 34 | S to N* | 9/56 | 2/29 | 7/95 |

| IMGT-HCDR2, codon 61 | S deletion | 18/56 | 0/29 | 1/95 |

| IMGT-HFR3, codon 66 | Y to H | 7/56 | 2/29 | 3/95 |

| IGHV4-34 sequences | Subset 4 | |||

| IMGT-HCDR1, codon 28 | G to D | 5/20 | 0/108 | 6/320 |

| IMGT-HCDR1, codon 28 | G to E | 8/20 | 6/108 | 18/320 |

| IMGT-HCDR1, codon 32 | G to D* | 7/20 | 20/108 | 49/320 |

| IMGT-HFR2, codon 40 | S to T | 10/20 | 29/108 | 45/320 |

| IMGT-HFR2, codon 45 | P to S | 10/20 | 17/108 | 33/320 |

| IGHV4-34 sequences | Subset 16 | |||

| IMGT-HCDR1, codon 28 | G to E | 6/7 | 6/108 | 18/320 |

| IMGT-HFR2, codon 40 | S to T | 4/7 | 29/108 | 45/320 |

| IMGT-HFR2, codon 45 | P to S | 3/7 | 17/108 | 33/320 |

| IGHV4-4 sequences | Subset 14 | |||

| IMGT-HCDR1, codon 33 | S to N | 3/4 | 0/17 | 8/90 |

| IMGT-HFR2, codon 40 | S to T | 4/4 | 4/17 | 12/90 |

| IMGT-HCDR2, codon 57 | Y to H | 4/4 | 3/17 | 7/90 |

| IMGT-HCDR2, codon 58 | H to P | 3/4 | 0/17 | 0/90 |

| IMGT-HFR3, codon 78 | I to M | 4/4 | 6/17 | 8/90 |

| IMGT-HFR3, codon 92 | S to N | 3/4 | 4/17 | 10/90 |

| Sequences . | Change . | CLL subset, n/N . | CLL heterogeneous, n/N . | Non-CLL, n/N . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IGHV1-2*02 sequences: IMGT-HFR2, codon 55 | W to R | Subset 1: 6/15 | 0/30 | 17/119 |

| IGHV1-2*02 sequences: IMGT-HFR2, codon 55 | W to R | Subset 28: 4/4 | 0/30 | 17/119 |

| IGHV3-21 sequences | Subset 2 | |||

| IMGT-HCDR1, codon 32 | S to T* | 11/56 | 6/29 | 12/95 |

| IMGT-HCDR1, codon 34 | S to N* | 9/56 | 2/29 | 7/95 |

| IMGT-HCDR2, codon 61 | S deletion | 18/56 | 0/29 | 1/95 |

| IMGT-HFR3, codon 66 | Y to H | 7/56 | 2/29 | 3/95 |

| IGHV4-34 sequences | Subset 4 | |||

| IMGT-HCDR1, codon 28 | G to D | 5/20 | 0/108 | 6/320 |

| IMGT-HCDR1, codon 28 | G to E | 8/20 | 6/108 | 18/320 |

| IMGT-HCDR1, codon 32 | G to D* | 7/20 | 20/108 | 49/320 |

| IMGT-HFR2, codon 40 | S to T | 10/20 | 29/108 | 45/320 |

| IMGT-HFR2, codon 45 | P to S | 10/20 | 17/108 | 33/320 |

| IGHV4-34 sequences | Subset 16 | |||

| IMGT-HCDR1, codon 28 | G to E | 6/7 | 6/108 | 18/320 |

| IMGT-HFR2, codon 40 | S to T | 4/7 | 29/108 | 45/320 |

| IMGT-HFR2, codon 45 | P to S | 3/7 | 17/108 | 33/320 |

| IGHV4-4 sequences | Subset 14 | |||

| IMGT-HCDR1, codon 33 | S to N | 3/4 | 0/17 | 8/90 |

| IMGT-HFR2, codon 40 | S to T | 4/4 | 4/17 | 12/90 |

| IMGT-HCDR2, codon 57 | Y to H | 4/4 | 3/17 | 7/90 |

| IMGT-HCDR2, codon 58 | H to P | 3/4 | 0/17 | 0/90 |

| IMGT-HFR3, codon 78 | I to M | 4/4 | 6/17 | 8/90 |

| IMGT-HFR3, codon 92 | S to N | 3/4 | 4/17 | 10/90 |

The frequency of changes among mutated sequences using the same IGHV gene was recorded in CLL sequences with stereotyped HCDR3s (sequences belonging to subsets), CLL sequences with heterogeneous HCDR3s, and sequences from normal or autoreactive clones. For this comparison, non-CLL sequences were pooled regardless origin (ie, whether they derived from normal or autoreactive B cells). Full details about non-CLL sequences (including origin) are provided in Tables S1 and S12.

These mutations, although very frequent among sequences of a subset, were also identified at a high frequency among either CLL sequences with heterogeneous HCDR3 or non-CLL sequences and, thus, were not considered as “subset-biased.”

Amino acid sequence alignments of 5 selected subsets defined by HCDR3 stereotypy. Sequence alignments for (A) subsets 1 and 28, (B) subset 2, (C) subset 4, (D) subset 14, and (E) subset 16 are represented as sequence logos85,86 to summarize a total of 106 sequences belonging to these selected subsets (Table S10). In each subset representation (ie, sequence logo), the colored letters above the line represent the amino acids used in that particular subset, and the gray letters shown upside-down below the line represent the germ line amino acid composition of the relevant IGHV gene. Each colored letter indicates an amino acid position where a mutation occurred. When more than one change was observed in a position, the letters representing each change are displayed as a stack. Thus, the size of the amino acid symbol represents the relative frequency of that amino acid at that position relative to all other mutations at that position in that subset. The height of the inverted germ line amino acid symbol is the sum of the heights of the upright amino acids. Blank spaces represent amino acids that are unchanged in the CLL IGHV sequence compared with the germ line sequence. Amino acids are colored based on their similarity in terms of their physicochemical properties: [GAPVLIM], blue; [FYW], purple; [STCNQ], green; [KRH], red; and [DE], orange. Sequence logos are vertically stretched so that the tallest upright stacks are of the same size, irrespective of the number of sequences. For example, in subset 4, 9 of 20 sequences carry E, whereas 5 of 20 sequences carry D at position IMGT/HCDR1-28 (Table S10); therefore, E is taller than D at that position in the sequence logo for subset 4 (C), whereas the height of the inverted germ line G is the sum of the heights of the upright D and E. Additional information about number of sequences with a certain amino acid change of total number of sequences in each subset can be found in Table 1 and Table S10. For clarity, only codons 27 to 104, corresponding to HCDR1-HFR3 of the V region, are shown. In panel B, the letter X denotes the serine deletion at IMGT/HCDR2 codon 59.

Amino acid sequence alignments of 5 selected subsets defined by HCDR3 stereotypy. Sequence alignments for (A) subsets 1 and 28, (B) subset 2, (C) subset 4, (D) subset 14, and (E) subset 16 are represented as sequence logos85,86 to summarize a total of 106 sequences belonging to these selected subsets (Table S10). In each subset representation (ie, sequence logo), the colored letters above the line represent the amino acids used in that particular subset, and the gray letters shown upside-down below the line represent the germ line amino acid composition of the relevant IGHV gene. Each colored letter indicates an amino acid position where a mutation occurred. When more than one change was observed in a position, the letters representing each change are displayed as a stack. Thus, the size of the amino acid symbol represents the relative frequency of that amino acid at that position relative to all other mutations at that position in that subset. The height of the inverted germ line amino acid symbol is the sum of the heights of the upright amino acids. Blank spaces represent amino acids that are unchanged in the CLL IGHV sequence compared with the germ line sequence. Amino acids are colored based on their similarity in terms of their physicochemical properties: [GAPVLIM], blue; [FYW], purple; [STCNQ], green; [KRH], red; and [DE], orange. Sequence logos are vertically stretched so that the tallest upright stacks are of the same size, irrespective of the number of sequences. For example, in subset 4, 9 of 20 sequences carry E, whereas 5 of 20 sequences carry D at position IMGT/HCDR1-28 (Table S10); therefore, E is taller than D at that position in the sequence logo for subset 4 (C), whereas the height of the inverted germ line G is the sum of the heights of the upright D and E. Additional information about number of sequences with a certain amino acid change of total number of sequences in each subset can be found in Table 1 and Table S10. For clarity, only codons 27 to 104, corresponding to HCDR1-HFR3 of the V region, are shown. In panel B, the letter X denotes the serine deletion at IMGT/HCDR2 codon 59.

Mutation targeting of superantigenic-binding motifs

A total of 706 IGHV3-expressing cases with less than 100% identity to germ line were examined for SHM targeting to the IGHV3-specific motif responsible for Staphylococcal protein A binding, which is mediated by a conformational surface generated by amino acids at 13 positions in the V region of IGHV3 subgroup genes.5 Nonconservative residue variations at 2 or more positions of this motif result in loss of Staphylococcal protein A binding activity.5 Overall, such variations were observed in 80 of 706 IGHV3-expressing cases (11.3%). Remarkably, significantly fewer changes were identified in rearrangements using the IGHV3-21 versus all other IGHV3 subgroup genes (13 of 79 (16%) versus 377 of 627 cases (60%; P < .01). Furthermore, the few amino acid changes that did occur in IGHV3-21 rearrangements (in particular, those carrying a stereotyped HCDR3) tended to be conservative; only 2.5% of IGHV3-21 sequences (2 of 79) carried 2 or more nonconservative amino acid changes of the motif, and neither of these belonged to subset 2. In contrast, although also relatively infrequent, up to three-fourths of amino acid changes identified in rearrangements of other IGHV3 genes (even those with a similar mutation load as the IGHV3-21 rearrangements) could be nonconservative.

A total of 126 IGHV4-34 sequences with less than 100% identity to germ line were examined for SHM targeting to the IGHV4-34–specific motif responsible for carbohydrate I binding, which is mediated by a hydrophobic patch in HFR1 involving residue W7 on β-strand A and the AVY motif (residues 24-26) on β-strand B.48 Notably, few IGHV4-34 sequences were altered at the 4 positions of the anti-I/i motif. Overall, there were only 0.9% to 4.9% nonconservative amino acid changes at these codon positions, and only one sequence had an amino acid change at more than one of the motif positions.

Discussion

In the present study, 1967 IGHV-D-J sequences from 1939 patients with CLL were analyzed for SHM patterns and compared with public non-CLL sequences from the IMGT database. Our series consisted of mutated and unmutated sequences at a frequency reported as typical for CLL.18,19,24,26,27

The gene repertoire of “truly unmutated” (100% identity to germ line) CLL sequences of the present series (n = 677) was extremely skewed and also characterized by significantly longer HCDR3s. Furthermore, 43.4% of “truly unmutated” sequences were found to belong to a subset with stereotyped HCDR3s. These observations suggest that the unmutated state in CLL could reflect selective pressures for maintaining germ line configuration.28,49

Unmutated BCRs of CLL B cells have recently been shown to be associated with autoreactivity and polyreactivity against molecules, such as DNA, insulin, and LPS, whereas BCRs in mutated CLL did not exhibit these polyreactive properties.50 Furthermore, as previously shown, the antigen binding site excluding the HCDR3 is exceptionally cross-reactive, at least until acted on by SHM.51,52 Based on the findings of the aforementioned studies and the results of the present study, it could perhaps be reasonable to speculate that unmutated BCRs with multiple specificities may provide CLL progenitors with a selective advantage because they widen the spectrum of potential antigenic stimuli.53,54

Previous studies in both normal and autoreactive B cells have shown that even a few mutations may be functionally relevant.55-57 Along these lines, in the present study, we also explored potential biologic implications of low mutational “load” in CLL. Therefore, SHM analysis was undertaken for the cohort of all 1290 sequences of the present series with less than 100% identity to germ line. At the cohort level, SHM patterns were typical of a canonical SHM process.6,46,47,58,59 However, important differences emerged from the analysis of SHM in subgroups of CLL sequences defined by: (1) IGHV gene usage, (2) HCDR3 length and degree of HCDR3 stereotypy, and (3) minimal versus borderline versus high mutation load.

Evidence for very precise SHM targeting was obtained by the evaluation of SHM patterns in different alleles of certain IGHV genes, indicating preferential selection of one allele over another. Remarkably, within the group of rearrangements using the IGHV1-69 gene, 87% of sequences expressing the *01 allele were “truly unmutated” versus only 50% of sequences expressing the *06 allele; yet, these 2 alleles differ from each other by only one amino acid at codon 82 (glutamic acid in IGHV1-69*01/lysine in IGHV1-69*06). Furthermore, all “minimally mutated” IGHV1-2 sequences of subsets 1 and 28, which carried as a single mutation the tryptophane-to-arginine (W-to-R) change at IMGT-HFR2 codon 55, expressed allele *02 of the IGHV1-2 gene. This change causes the IG sequence to become more like the IGHV1-2*01 allele because an arginine at that position is only present in the germ line configuration of the IGHV1-2*01 allele. Of note, within the comparable non-CLL group, 10 of 17 IGHV1-2*02 sequences carrying this mutation encoded autoantibodies, of which 7 were rheumatoid factors (Table S12). These findings illustrate that even very slight alterations in IG sequence appear to be selected for, perhaps because they may confer a clonal advantage.

At the level of individual IGHV genes, the most distinctive, often “CLL-biased,” SHM patterns were observed in groups of sequences using the IGHV3-21 and IGHV4-34 genes. Although frequently mutated, almost one-fourth of IGHV3-21 cases in our series had a low mutation load and fell into the “borderline/minimally mutated” group. The distribution of R mutations and the nucleotide substitution spectra of IGHV3-21 sequences differed significantly from other IGHV3 genes. Of note, IGHV3-21 sequences with stereotyped HCDR3s belonging to subset 2 showed 0.8- to 2.4-fold lower targeting of all regions (except HCDR2) than non-subset 2 IGHV3-21 sequences. Furthermore, several recurrent amino acid changes were observed among subset 2 IGHV3-21 sequences, in particular at HCDR2 codons. Remarkably, a serine deletion at IMGT/HCDR2 codon 59 was detected in 18 IGHV3-21 CLL sequences, all expressing stereotyped BCRs. This finding confirms and extends a recent report from our group, which first suggested that this deletion is “CLL-biased.”37 Therefore, although IGHV3-21 sequences are generally less targeted by SHM than other IGHV3 genes, the observed mutations appear to be very precisely and effectively targeted, indicating selection by specific antigen(s). Along these lines, it is also perhaps relevant that IGHV3-21 sequences from our series, in particular those carrying stereotyped HCDR3s, showed a strong tendency to retain germ line configuration in the binding motif for Staphylococcal protein A, the prototype for a class of naturally arising proteins that have the properties of model B-cell superantigens.5 At present, the biologic and clinical implications of this observation (if any) remain unknown.

The IGHV4-34 gene encodes antibodies, which are intrinsically autoreactive in the germ line state by virtue of recognition of the N-acetyllactosamine (NAL) antigenic determinant of the I/i blood group antigen.60 Anti-I/i IGHV4-34 antibodies also bind the linear poly-NAL in the B-cell isoform of CD45.60 The I/i antigen may be expressed in oxidized apoptotic cells, and CD45 is expressed by preapoptotic T cells61,62 ; these findings explain why IGHV4-34 antibodies bind apoptotic cells.63 B cells whose surface receptors bind to apoptotic cells may serve “housekeeping” functions by removing cellular debris.64 Thus, it is possible that immature B cells expressing IGHV4-34 participate in the removal of apoptotic cell remnants. However, given the remarkable cross-reactivity of IGHV4-34 antibodies against several auto- and exo-antigens,65-67 if immature IGHV4-34–expressing B cells participate in the uptake of apoptotic cell remnants in the bone marrow, at the same time, they must be undergoing modifications to ablate self-reactivity.68 These modifications may be introduced by somatic diversification mechanisms, such as SHM and receptor editing.66,69,70 In the present study, 79% of IGHV4-34 CLL sequences were mutated, in keeping with previous reports in smaller series.24,26,27,34 In line with the reasoning presented in this paragraph about the physiological function of IGHV4-34 antibodies, this trend might reflect the fact that IGHV4-34 sequences must undergo SHM to negate their autoreactivity and be sufficiently “safe” to be allowed into the functioning IG repertoire.

Previous studies have demonstrated that the region of the IGHV4-34 molecule that cross-reacts with the I antigen is a hydrophobic patch in HFR1 created by a discontinuous sequence involving a W residue at codon 7 and the AVY triplet at codons 24-26.48 On examination of the anti-I/i-binding motif in the HFR1 of IGHV4-34 CLL sequences from our series, we observed that each of the 4 positions of the W-AVY motif was very infrequently mutated. Most interesting, however, was the fact that none of subset 4 or subset 16 IGHV4-34 sequences were among those carrying an altered motif. Thus, in theory, these IGHV4-34 expressing CLL cells could still be bound (and stimulated for clonal expansion) by I/i antigens or the CD45 on B cells, similar to what has been reported previously for normal B cells.71 In this context, Catera et al recently demonstrated that 3 IGHV4-34 recombinant CLL antibodies with stereotyped BCRs, similar to our subset 4 sequences, bound to viable B cells via the NAL epitope.72

HCDR3 sequence motifs enriched in basic amino acids have been shown to correlate strongly with reactivity of IGHV4-34 antibodies against both B cells and DNA.73-75 All subset 4 IGHV4-34 CLL sequences from our series have high HCDR3 isoelectric point values, and all carry a couplet of basic residues (arginine-arginine or arginine-lysine) at the IGHD–IGHJ junction. High isoelectric point, overall positive charge, and increased numbers of arginine residues are frequent features of many pathogenic anti-DNA antibodies.57,76-78 Although it is not possible to accurately predict IG specificity by sequence analysis alone, these findings suggest that subset 4 BCRs may have anti-DNA specificity.

In transgenic mouse model systems, introduction of acidic residues (particularly aspartic acid) by SHM is a means to edit anti-DNA reactivities.56,69,79 A remarkable analogy can be drawn with SHM patterns observed in CLL sequences of subsets 4 and 16 from our series. Aspartic and glutamic acid residues introduced by SHM were observed with a high frequency in the HCDR1 of these sequences. Along these lines, it would be tempting to speculate that modification of subset 4 and 16 IGHV4-34 sequences by SHM in precursors of the CLL clones significantly reduced or eliminated the postulated anti-DNA reactivity. This hypothesis is supported by the study of Herve et al,50 in which unmutated revertant antibodies engineered from mutated IGHV4-34 recombinant antibodies of CLL patients, similar to subset 4 antibodies from the present series, showed increased HEp-2 reactivity and/or acquired polyreactivity. Therefore, the SHM patterns observed among IGHV4-34 CLL sequences, in particular, those expressed by subset 4 and subset 16 cases, may induce a state of diminished responsiveness toward a selecting antigenic element. However, these IGHV4-34 clones could retain the ability to engage in superantigen-like interactions with various auto- and exo-antigens via their preserved (non-mutated) HFR1 motifs. Therefore, in principle, CLL progenitors could be activated or “kick-started” on infection or reactivation by certain microbial pathogens (CMV or EBV might be such pathogens80-84 ) and thus receive signals promoting survival, expansion, malignant transformation, and potentially clonal evolution.

In conclusion, groups of patients with CLL using certain IGHV genes, in particular, subsets grouped according to HCDR3 composition, evidently carry shared, “stereotyped” mutations across the entire IGHV gene sequence. Furthermore, the mutation pattern within these subgroups was not only gene- and subset-biased, but also, in most cases, “CLL-biased.” The finding of such “stereotyped” mutations in mutated CLL sequences carrying stereotyped HCDR3s indicates that the leukemic progenitor cells may have responded in a similar fashion to the selecting antigen(s). Remarkably, as shown in the present study, selection for individual mutations is evident even in subsets with minimally mutated sequences, indicating a functional purpose for these modifications. Finally, the presence of stereotyped mutations is strong evidence that not only the HCDR3 but also other regions of the IG molecule could actively participate in antigen recognition and thus be involved in the development and evolution of the CLL clone.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Prof Marie-Paule Lefranc and Dr Veronique Giudicelli, Laboratoire d'Immunogenetique Moleculaire, Universite Montpellier II, Montpellier, France, for their enormous support and help with the large-scale immunoglobulin sequence analysis throughout this project. The authors also thank Prof Göran Roos, Department of Medical Biosciences, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden; Prof Christer Sundström, Department of Genetics and Pathology, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden; Dr Mats Merup, Department of Medicine, Karolinska University Hospital, Huddinge, Sweden; Dr Lyda Osorio, Department of Microbiology, Tumor and Cell Biology, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden; and Prof Juhani Vilpo, Laboratory Center, Tampere University Hospital, Tampere, Finland, for providing samples and clinical data concerning Swedish and Finnish CLL patients; and Dr Hedda Wardemann, Max-Planck Institute for Infection Biology, Berlin, Germany, for her provision of antibody sequences of IgG+ memory B cells from healthy donors. We also acknowledge the contribution of Dr Ulf Thunberg, Dr Tatjana Smilevska, Maria Norberg, Arifin Kaderi, Ingrid Thörn, and Kerstin Willander to the sequence analysis.

This work was supported by the Swedish Cancer Society, the Swedish Research Council, Medical Faculty of Uppsala University, Uppsala University Hospital, and Lion's Cancer Research Foundation, Uppsala, Sweden; the Networks of Excellence BioSapiens (contract number LSHG-CT-2003-503265) and Experimental Network for Functional Integration (ENFIN) (contract number LSHG-CT-2005-518254), both funded by the European Commission (Computational Genomics Unit, Thessaloniki, Greece); the Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC, Milano), the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the CLL Global Research Foundation (Milano, Italy); an Intergration of researchers from abroad in Greece's Research and Technology (ENTER) career development award from the General Secretariat for Research and Technology, Greek Ministry of Development (N.D.); and a fellowship from the Foundation Anna Villa e Felice Rusconi, Varese, Italy (C.S.).

Authorship

Contribution: F.M., N.D., and A.H. performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; G.T. performed research and wrote the paper; M.B., C.S., K.K., F.B.-M., C.M., and D.V. performed research; N.L., A.A., and F.C.-C. provided samples and associated data; A.T. and C.O. supervised research; C.B., P.G., F.D., R.R., and K.S. designed and supervised the research and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Paolo Ghia, Università Vita-Salute San Raffaele, Via Olgettina 58, 20132 Milano, Italy; e-mail: ghia.paolo@hsr.it.

References

Author notes

F.M., N.D., and A.H. contributed equally to this work.

![Figure 4. Amino acid sequence alignments of 5 selected subsets defined by HCDR3 stereotypy. Sequence alignments for (A) subsets 1 and 28, (B) subset 2, (C) subset 4, (D) subset 14, and (E) subset 16 are represented as sequence logos85,86 to summarize a total of 106 sequences belonging to these selected subsets (Table S10). In each subset representation (ie, sequence logo), the colored letters above the line represent the amino acids used in that particular subset, and the gray letters shown upside-down below the line represent the germ line amino acid composition of the relevant IGHV gene. Each colored letter indicates an amino acid position where a mutation occurred. When more than one change was observed in a position, the letters representing each change are displayed as a stack. Thus, the size of the amino acid symbol represents the relative frequency of that amino acid at that position relative to all other mutations at that position in that subset. The height of the inverted germ line amino acid symbol is the sum of the heights of the upright amino acids. Blank spaces represent amino acids that are unchanged in the CLL IGHV sequence compared with the germ line sequence. Amino acids are colored based on their similarity in terms of their physicochemical properties: [GAPVLIM], blue; [FYW], purple; [STCNQ], green; [KRH], red; and [DE], orange. Sequence logos are vertically stretched so that the tallest upright stacks are of the same size, irrespective of the number of sequences. For example, in subset 4, 9 of 20 sequences carry E, whereas 5 of 20 sequences carry D at position IMGT/HCDR1-28 (Table S10); therefore, E is taller than D at that position in the sequence logo for subset 4 (C), whereas the height of the inverted germ line G is the sum of the heights of the upright D and E. Additional information about number of sequences with a certain amino acid change of total number of sequences in each subset can be found in Table 1 and Table S10. For clarity, only codons 27 to 104, corresponding to HCDR1-HFR3 of the V region, are shown. In panel B, the letter X denotes the serine deletion at IMGT/HCDR2 codon 59.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/111/3/10.1182_blood-2007-07-099564/6/m_zh80040813050004.jpeg?Expires=1769127939&Signature=A~GuRCnGcXLovgcMD~EucgJDPHH4J4d~Ad6v6jT4z5P0fLiZtZaSdH4fg0TTGOqp1HKmo~BFPAhTZ3mDFsqywihn7lPL~KFnegHaYdtNWuQV2O7-J6XxocsUC4Sq2-UNLR06mW7RxNlfI8Qk2OWkNT-Cq0QxPkRt2E8g3Tq29Ye4qFh-UKsJA1sahZy9LkmCZft9ubrLoIVJxJAnD9OVr0zKXPQwbRrdNsoa7yTH6zN4IrxgT79X4wKAh~4gxinpUgnjQYUkT6DsLGGTllOEl87NIGQvtzhO9sqDHBM-KEoGoxyEITSCRbB3EeR7cnNYY-ewkwLL1g~xjjuqnpaIEA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)