In this issue of Blood, Hexner and colleagues report that lestaurtinib (CEP701), an orally applicable small molecular inhibitor of FLT3, also targets JAK2 and holds promise as a candidate drug for the treatment of patients with myeloproliferative disorders (MPDs).

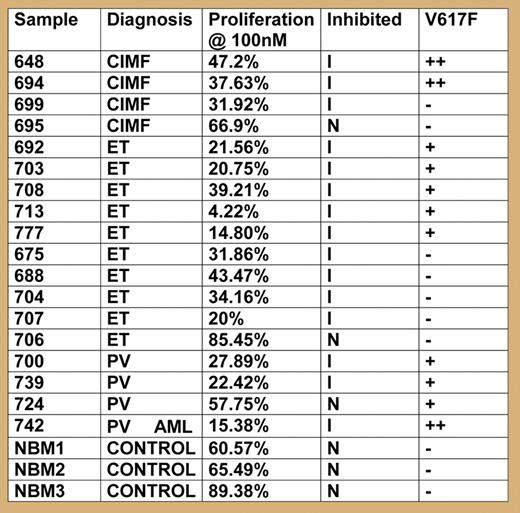

Lestaurtinib has been shown previously to be well tolerated and to have clinical activity in phase 1 and 2 trials of acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) patients carrying activating FLT3 mutations.1 Screening of multiple kinases in vitro now reveals that lestaurtinib also inhibits JAK2 at low nanomolar concentrations. Because the majority of patients with MPDs carry activating mutations in JAK2 (JAK2-V617F or exon 12 mutations),2 blocking JAK2 can be expected to have beneficial effects. This compound targets the ATP-binding pocket of Jak2 and is therefore not expected to discriminate wild-type (WT) from V617F Jak2. Indeed, a cell line (HEL92.1.7) homozygous for JAK2-V617F, but not expressing FLT3, showed reduced proliferation and cell survival in the presence of lestaurtinib. Furthermore, primary cells from MPD patients that were expanded in vitro were more sensitive to inhibition by lestaurtinib than cells form healthy control subjects. Interestingly, cells from MPD patients negative for JAK2 mutation were also sensitive to growth inhibition by lestaurtinib (see figure). Further biochemical analysis of signaling in primary cells revealed dose-dependent inhibition of JAK2 and downstream targets such as STAT3, STAT5, AKT, or ERK.

Proliferation in the presence of lestaurtinib (100 μM) compared to untreated cells was measured in liquid culture.

Proliferation in the presence of lestaurtinib (100 μM) compared to untreated cells was measured in liquid culture.

The chances of lestaurtinib succeeding as a therapeutic agent depend on several factors. First, and most important, is the biology of the disease: the phenotypic manifestations of chronic MPDs seem to be driven by a single (or few) mutations leading to constitutive activation of a protein kinase such as ABL, JAK2, or PDGFR.2 In contrast, acute leukemia, characterized by expansion of cells with a differentiation block, appears to be the product of several functionally cooperating mutations. This may explain why the majority of chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) patients in chronic phase can be successfully treated with imatinib as a single drug, whereas first clinical trials with small molecular kinase inhibitors in AML show only transient clinical responses to these agents alone. Recent work in vitro as well as with mouse models of JAK2-V617F–induced MPDs suggests that blocking JAK2 kinase activity with small molecular inhibitors might be an efficient tool for reducing the cellular mass responsible for the typical clinical complications of these disorders.3,4

Second, considering the long life expectancy of MPD patients, a successful compound must have a high therapeutic index. Lestaurtinib was well tolerated in phase 1 and 2 studies, and therefore has already passed its first important test. Nevertheless, inhibition of JAK2 raises concerns, since JAK2 is required for signaling by the receptors for erythropoietin, thrombopoietin, and in part, G-CSF. In this respect, it is encouraging that cells carrying JAK2-V617F were more sensitive to the inhibition of les-taurtinib than cells with WT JAK2. Conversely, cells from MPD patients negative for JAK2-V617F were also inhibited by lestaurtinib. This could be interpreted to mean that activation of JAK2 signaling is a common pathway of pathogenesis in MPDs. Alternatively, lestaurtinib may have additional beneficial “off-target” effects by inhibiting other, as-yet-unknown kinases that act as cooperating cellular signaling pathways.

The work by Hexner and colleagues shows that lestaurtinib can be added to a rapidly growing list of small molecules with inhibitory effects against JAK2. Information about the structure of the complete human kinome, in conjunction with high-throughput screening platforms, may reveal other hidden gems and allow further expansion of targeted cancer therapeutics. The discovery of JAK2 mutations in MPDs has initiated an exciting new phase for clinicians and basic scientists interested in MPDs, and has already substantially improved diagnostics and advanced our knowledge of MPD pathogenesis. In fewer than 3 years since their discovery, there has developed the exciting prospect that patients with MPDs may soon benefit from targeted treatment for their disease.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author is a consultant for Genentech (South San Francisco, CA). ■

REFERENCES

National Institutes of Health

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal